Coins of Ancient India From the Earliest Times Down to the Seventh Century A.D.by Major-General Sir Alexander Cunningham, K.C.I.E., C.S.I., R.E.

1891

[SEARCH: "DATTA" = 2 REFERENCES]

1st Reference:Ayodhya. Plate IX. Ayodhya, the ancient kingdom of Rama, is now known by the shorter name of Oudh (or Awadh). The old capital of Ayodhya is still known as Ajudhya, and there all the coins in the accompanying Plate IX. were obtained. A few coins of this class have been published by Mr. Carnac, in the Bengal Asiatic Society's Journal for 1880, Plates XVI. and XVII., but without any notice of their findspots. Amongst them is a new type of Visakha Deva, which I have given in Plate IX., fig. 7.

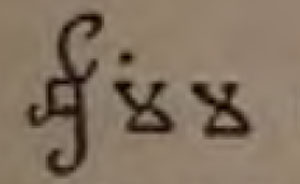

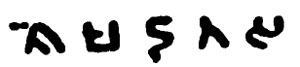

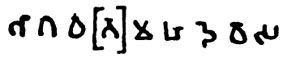

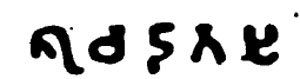

Plate IX., fig. 7.In my account of Ayodhya47 [Archaeol. Survey of India, i. 818.] I have identified it with the Visakha of the Chinese pilgrim, Hwen Thsang, and I have suggested that this name was perhaps derived from the famous lady Visakha, the daughter of the rich merchant Dhananjaya, of Sakata or Ayodhya. On some of the oldest coins of Ajudhya will be found the names of Dhana-deva and Visakha Datta [VISAKHA-DEVA?], which may very plausibly be connected with those of the rich merchant and his daughter.

Plate IX., fig. 7.In my account of Ayodhya47 [Archaeol. Survey of India, i. 818.] I have identified it with the Visakha of the Chinese pilgrim, Hwen Thsang, and I have suggested that this name was perhaps derived from the famous lady Visakha, the daughter of the rich merchant Dhananjaya, of Sakata or Ayodhya. On some of the oldest coins of Ajudhya will be found the names of Dhana-deva and Visakha Datta [VISAKHA-DEVA?], which may very plausibly be connected with those of the rich merchant and his daughter. The coins are certainly not older than the second century B.C., but, as both names were popular, they would probably be repeated in many families of Ayodhya. The coins themselves do not present any traces of Buddhism except the Bodhi tree and the combined symbol of the Tri-ratna and Dharma-chakra. But neither do they show any special traces of Brahmanism, except in the names of Siva and Vayu.

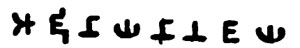

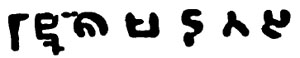

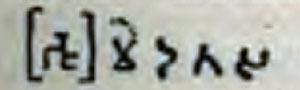

2nd ReferenceSiva-Datta.  Plate IX., Fig. 10

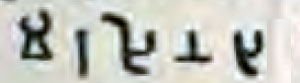

Plate IX., Fig. 10Plate IX., Fig. 10. AE. 0-6. Weight 24 grains.

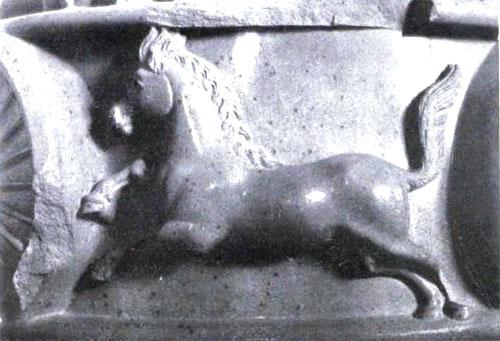

Obv. — Elephant moving to l., towards symbol on pillar.

Indian legend, Siva-datasa. Rev. — Tree inside railing.

*************************

Coins of Ancient India: Catalogue of the Coins in the Indian Museum, CalcuttaVolume 1

by Vincent A. Smith, M.A. F.R.N.S., M.R.A.S., I.C.S. Retd.

1906/1972

[SEARCH: "DATTA" = 37 REFERENCES]

1st Reference:Section VI. LOCAL COINS OF NORTHERN INDIA

INTRODUCTION The four groups of coins described in this Part have been classed together as being severally assignable to fairly definite localities in Northern India. The coins of each group are found predominantly in the districts named, and are not common elsewhere. The first definite step in such localization of the ancient coinages was taken by the publication in 1891 of Coins of Ancient India by Sir Alexander Cunningham, the greatest Indian numismatist since James Prinsep. Sir Alexander's unique experience extending over considerably more than half a century enabled him to accumulate a mass of knowledge, both general and special, concerning all classes of Indian coins, which nobody can hope to rival.

Although he published comparatively few details about the provenance, or find-spots, of individual coins, his general statements on the subject are of the highest value. His announcement, for instance, that all the coins figured in Plate IX of the work above referred to were obtained at Ajodhya, furnishes a secure basis for the classification of many pieces which would otherwise embarrass the numismatist. In the same way the assignment of the other classes of coins treated in this section to Avanti, Kosam, and Taxila respectively rests primarily upon Sir Alexander Cunningham's unequalled personal knowledge of the distribution of Indian coins.

As Professor Rapson has pointed out, the hope of further advance in our knowledge of the ancient currencies of India depends largely on recognition of the local limits of each class of coin. It is very unfortunate that the recorded information about the find-spots of coins is so scanty, but it is some satisfaction to be able to assign even a few groups to their proper local position. Coins of copper, including bronze of sorts, do not, as a rule, wander very far from their place of issue, and, inasmuch as nearly all the ancient Indian coins may be classed under the heading ‘copper’, evidence of their provenance goes a long way towards determining approximately the locality of their mints. AJODHYA The ancient city of Ajodhya on the Ghaghra (Gogra) river to the east of the province of Oudh is famous in Hindu legend as the capital of Rama, but is now a comparatively unimportant town, except as a place of pilgrimage. It has been overshadowed, and, to a large extent, replaced by the modern city of Faizabad (Fyzabad), N. lat. 26°46’ 45”, E. long. 82°11’40”, a few miles distant, built in no small degree from the materials of Rama’s capital. Coins obtained at Fyzabad may be considered as coming mostly from Ajodhya.

The ancient history of Ajodhya is lost, and the attempts of the local Brahmans to supply the loss are worthless. No independent record exists of any of the Rajas whose coins are described in the following pages, and we can only guess their age by considering the style of the coins and the script of the legends. Cunningham held that the most ancient coins, those of Dhanadeva and Visikhadeva, are ‘certainly not older than the second century B.C.’, and this determination may be accepted, so far as the inscribed coins are concerned. Of course many of the punch-marked and cast coins without legends may be much older. The coins of both — Visikhadeva and Dhanadeva were simply cast in moulds, and evidently are of much the same date. Either prince may be regarded as the predecessor of the other.

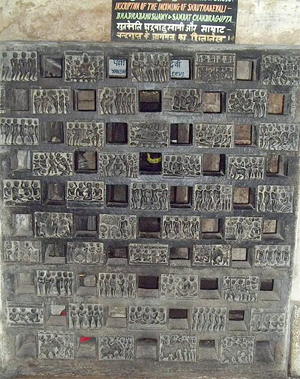

The coins, Nos. 8-11, doubtfully ascribed to Sivadatta, are also cast; as are the curious little pieces, Nos. 12 and 13 (PL XIX, 14), exhibiting the fish, svastika, ‘taurine, and an object which seems to me to be intended for a steelyard balance, but is described by Cunningham as an axe.

2nd Reference:CATALOGUE: COINS OF AJODHYA, FROM ABOUT 150 B.C. TO 100 A.D.

Serial No. / Museum / Metal, Weight, Size / Obverse / Reverse...

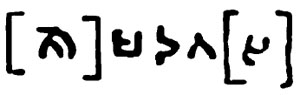

(?) KING SIVA-DATTA

8 / A.S.B. / AE pale bronze rect. 16-7-65 x -55 / Elephant moving l. towards a tree or symbol in railing. Br. legend above, (Siva ?)datas. / Sundry symbols, including a form of the ‘Ujjain symbol’ ; ‘the central device may be a degraded form of the goddess seated on lotus (cp. C. A. I., Pl. IX, 10, 11).

9 / A.S.B. / AE pale bronze or brass rect. 36-7-65 x -56 / Similar; in worse condition. / Defaced.

10 / A.S.B. / AE brass rectang. 22-6 -62 x -53 / Similar; legend illegible. / Similar to No. 8; but the central device is reduced to mere lines.

11 / A.S.B. / AE brass rect. 44-3 -6 / Ditto; ditto. / Ditto; ditto; a thicker coin (Nos. 8-11 are cast coins like those of Dhanadeva, but in poor condition, and perhaps later in date). 3-18 ReferencesSECTION IX. THE RAJAS AND SATRAPS OF MATHURA AND VIRASENA

INTRODUCTION

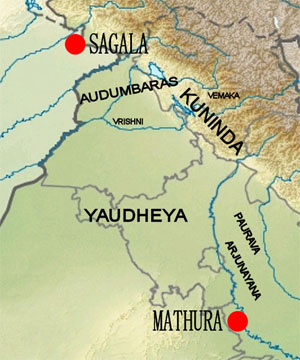

THE RAJAS AND SATRAPS OF MATHURA Recent research has disclosed the names of a large number of early Rajas ruling either at Mathura (Muttra, N. lat. 27°30'13”, E. long. 77°43’45”), or over territories in the immediate neighbourhood of that ancient city. The Rajas whose coins are described in the catalogue are Balabhuti, Purushadatta, Bhavadatta (unpublished), Uttamadatta, Ramadatta, Gomitra, Vishnumitra, Brahmamitra, and ? Surya (Suya). There is also a doubtful name (uncertain, No. 1) which may be Ghosha. Other names known are Seshadatta, Kamadatta, Sivadatta, and Sisuchandradatta or -chandrata (?) (J. R.A.S, 1900, pp. 109-15). Cunningham knew of only three specimens of Balabhuti; four more are now described, and three bad specimens have been excluded.

The coins of Purushadatta also are rare. Carlleyle found a specimen at Bhuila Dih in Basti District, U.P., to the east of Oudh (Reports, xii. 145, 164). Bhavadatta is new, but see

J.R.A.S., 1900, p. 113. Three are now added to the five specimens of Uttamadatta previously known. The coins of Ramadatta are fairly common. Carlleyle found examples associated with coins of the satraps Ranjubula and Sodasa at Indor Khera in the Bulandshahr District, U.P. (Reports, xii, 43).

The coins of Gomitra, Vishnumitra, Brahmamitra, and Sirya (Suya) are scarce, but sometimes obtainable at Mathura. They are, I think, later than those of the princes previously named.

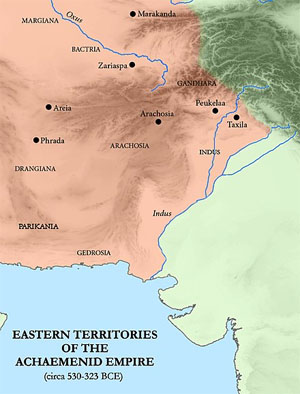

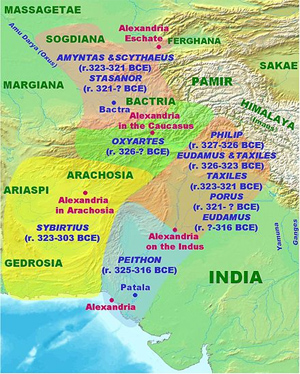

Probably all these Rajas, some of whom may have been contemporary with each other, are earlier than the foreign satraps with Persian names. The most ancient of the satraps seem to be Hagana and Hagimasha, presumably brothers, who introduced a reverse device of a horse. The coins of Hagamasha as satrap alone are fairly common, and it would appear that he was the younger brother and survivor of Hagana. He seems to have been directly followed by Ranjubula or Rajuvula, who struck hemidrachmae in base silver, resembling and associated with the coins of Strato II, as well as bronze coins after the manner of the Rajas: Sodasa was undoubtedly the son of Ranjubula, and if we knew the era of the date 72 on his Mathura inscription the chronology would be clear. The Mathura satraps were intimately associated with the satraps of Taxila, whose few coins are not represented in this catalogue.

The satraps of both Taxila and Mathura by their use of a Persian title and by their names plainly show their connexion with the Persian or Parthian empire; and their rule was, I believe, a consequence of the conquest of the kingdom of Taxila by the Parthian king Mithradates I in or about 138 B.C. Ranjubula and Sodasa may be placed, according to my view, in the last quarter of the second century B.C., somewhere about 125-100 B.C., and the date 72 of Sodasa’s inscription must be interpreted accordingly. But this theory of the chronology is not universally accepted. Cunningham obtained thirteen coins of Ranjubula at Sultanpur in the Jalandhar (Jullunder) District, Panjab (Reports, xiv. 57). His coins have been procured also at Sankisa in the Farrukhabad District, U.P., and, in association with those of his son Sodasa, at Padham in the adjoining District of Mainpuri (Reports, xi. 25, 38). The distribution of the coins of Ranjubula led Cunningham to believe that his dominions included a large portion of north-western India, extending from Kangra, at the foot of the Himalayas, to Multan in one direction, and to Mathura in the other (Reports, iii. 41). But this estimate may be considered somewhat excessive.

The printed notices of the coins of the Rajas and Satraps of Mathura have been indicated sufficiently above and in the catalogue. The position of the satraps in relation to the Parthian empire has been discussed briefly (p. 21) in my essay entitled ‘The Indo-Parthian Dynasties, from about 120 B.C. to 100 A.D.’ (Z.D.M.G., January, 1906).

VIRASENA The coins of this ruler are most readily procured in the Mathura bazaar, where Cunningham obtained about a hundred. Carlleyle got thirteen at Indor Khera in the Bulandshahr District, while Mr. Burn and others have collected them in the Etah (Ita) District, as well as at Kanauj and other places in the neighbouring Farrukhabad District. It is clear, therefore, that Virasena ruled in the Central Doab, between the Ganges and Jumna. His coins are scarcer in the Panjab. Four specimens are in Rodgers’ collection at Lahore, and I formerly possessed an exceptionally minute one (diam. ‘3), which came from the Panjab. The commonest variety consists of the small rectangular pieces about -45 in diam., with a palm-tree on obverse and the rude outline of a crowned female figure on the reverse. Sometimes the reverse is blank. The variety with the name only in an incuse on obverse, and blank or animal reverse (Catal. Nos. 1-3) seems to be rare, and has not been published previously. I am disposed to think that the coins of this class were issued by an earlier homonymous king. Mr. Burn has one round coin of Virasena, but I have seen only the rectangular pieces. Mr. Burn found a brief inscription with the name Virasena in the year 1896 at Jankhat in the south of the Farrukhabad District, which probably refers to the Raja who issued the ‘palm-tree’ coins. I read the date on a rough copy as 113 Grishma (i.e. hot season), which probably indicates that the record is dated in the year 113 of the era used by the Kushan kings, which, according to my view, began about 120 A.D. If so, the date of the inscription would be about 335 A.D. The characters of the legends on the ‘palmtree’ coins may be as late, although they look rather earlier. Mr. Burn was inclined to read the date of the inscription as 13; but, apparently, that would fall in the reign of Kanishka, and it is unlikely that he would have allowed Virasena to coin extensively in a province adjoining the Panjab.

See C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 18; Carlleyle in Reports, xiv. 41;

Rapson and Burn in J.R.A.S., 1900, pp. 115, 552.

CATALOGUE

RAJAS OF MATHURA, ABOUT SECOND CENTURY B.C.

Serial No. / Museum / Metal, Weight, Size / Obverse / ReverseBALABHUTI 1 / I.M. / AE 84.7 -7 / Figure facing front, r. hand raised; early Br. legend on upper margin, [Ra]jno Balabhutisa / Rows of dots (C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 8).

2 / I.M. / AE 72.7 -7 / Ditto; ditto; a symbol to l. of figure / Obscure, defaced.

3 / I.M. / AE 72 -73 / Ditto; ditto; the symbol to l. is [x], and to r. [x] / Two rows of dots and (?).

4 / I.M. / AE 81 -62 / Device defaced; legend, [Ba]labhutisa / Defaced; thick coin.

PURUSHADATTA 1 / I.M. / AE 99 -8 / Device defaced; early Br. legend, Purushadatasa. / Defaced (C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 17).

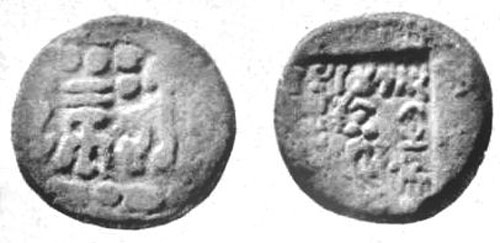

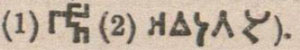

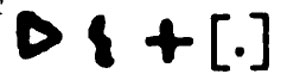

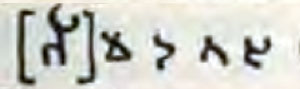

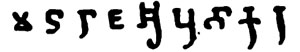

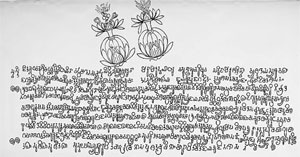

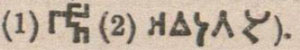

2 / I.M. / AE brass 79-5 -7 / Standing figure; symbol to r.; legend, [Pu]rushadatasa. / Apparently elephant l., with two rows of dots above (Pl. XXII, 10). BHAVADATTA 1 / A.S.B. / AE brass 100-5 -8 / Traces of standing figure and same symbols as on coins of Balabhuti. Two-line Br. legend, (1) Rajno, (2) Bhavadatasa (much worn, but reading certain, (1) [x] (2) [x]).

/ Elephant moving r. (Unpublished; cp. J.R.A.S., 1900, p. 113, fig. 13; with elephant l., but probably same legend.)UTTAMADATTA 1 / A.S.B./ AE brass 69 -7 / Standing figure, with r. hand raised, as usual in this class; to l. a conventional tree. Legend, Raja (not Rajnno) Utamadatasa. / Elephant in high relief, moving r. (Pl. XXII, 11; also in J.R.A.S., 1900, p. 109, fig. 8).

2 / I.M. / AE copper 55-8 -7 / Standing figure; Utamadatasa. / Defaced.

3 / I.M. / AE copper 54 -63 / Ditto; [U]tamadatasa. / Elephant moving r.RAMADATTA 1 / I.M. / AE 108-2 -82 / Usual standing figure; early Br. legend in large characters, (Ra)madatasa. / Obscure; should be three elphants with riders (Pl. XXII, 12).

2 / I.M. / AE 104 -85 / Similar; legend complete. / Defaced.

3 / I.M. / AE 94-5 -87 / Similar; Rama(data)sa. / Ditto; two rows of dots.

4 / I.M. / AE 95 -82 / Similar; kamada[tasa]; tree l. / Trident; dots above

5 / I.M. / AE 104 -88 / Similar; the figure stands on a low railing or pedestal; Rama(da)tasa. / Two rows of dots above, apparently indicating the heads of elephants.

6 / A.S.B./ AE imperfect -88 / Similar; Rama. / Similar, defaced; a protuberance left in casting.

7 / A.S.B. / AE 90-5 -87 / Similar; traces of legend. / Obscure

8 / A.S.B. / AE 71 -7 / Similar; datasa. / Ditto; worn smooth.

Doubtful 9 / I.M. / AE 95-2 -93 / Standing figure countersunk in oblong incuse r.; an obscure symbol in shallow square incuse 1. / Defaced; cast.

10 / I.M. / AE 108-3 -82 / Similar to No. 9; but oblong incuse l., and figure radiate; no second incuse. / Defaced; cast.

11 / I.M. / AE 85-6 -78 / Similar, but the single oblong incuse is r. / Ditto; apparently an elephant’s head and trunk in centre.

GOMITRA 1 / A.S.B. / AE oblong 98 -75 x -6 / The usual standing figure; tree l.; another symbol r. Br. legend above, Gomitrasa, indistinct.1 / Obscure; cast (C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 11; J.R.A.S., 1894, p. 554, fig. 11).

2 / A.S.B. / AE brass circular / Similar / Defaced; thick, die-struck

VISHNUMITRA 1 / A.S.B./ AE copper / Usual standing figure and tree. Legend, Vishnumitrasa, indistinct. / Worn smooth (J.R.A.S., ut sup., Fig. 12).

BRAHMAMITRA 1 /A.S.B./ AE copper -92 -75 / Usual standing figure and tree. Legend, imperfect, Brahmamitrasa. / Apparently blank; a protuberance left in casting.

2 / A.S.B. / AE 89 -3 -7 / Similar / Traces of a device.

3 / A.S.B. / AE 65-5 -65 / Ditto / Apparently blank. (All very poor; see C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 12.)

UNCERTAIN 1 / I.M. / AE 17-8 -6 / Standing figure, very rude. Legend seems to include [bhaga]vate gh[o]- satha (?). / Horse moving l.; thin coin.

2 / I.M. / AE 99 -8 / Usual standing figure; rajno; possibly Gomitra. / Defaced.

3 / A.S.B. / AE brass 113-3 -8 / Usual figure; ‘Ujjain symbol’ r.; legend illegible. / Probably three elephants.

4 / I.M. / AE 86-2 -7 / Usual figure; (data) maharajasa. / Defaced.

5 / I.M. / AE 65-2 -7 / Ditto; traces of maharajasa. / Three figures, each with four dots for upper parts, possibly elephants facing.

6 / I.M. / AE 67-8 -65 / Ditto; rajasa. / Apparently elephants facing.

7 / I.M. / AE 30 -47 / Device uncertain. Legend perhaps [Bha]vada-tasa. / Defaced.

8 / I.M. / AE brass 95-5 -7 / Usual figure. Legend probably Suya (Surya) mitasa. / Defaced.

1 It is possible to read these legends either as -mitrasa or -mitasa, ta being sometimes written with a downward prolongation on right side.

SATRAPS OF MATHURA, about 125 To 80 B.C. Copper or brass

HAGANA AND HAGAMASHA 1 / A.S.B. / AE 54-8 -65 / Three-line legend (1) Khatapana (2) Haganasa (3) Hagamashasa, ‘[Coin] of the satraps Hagana and Hagamasha’; at top, female figure parallel with legend; at r. side, thunderbolt (vajra). / Horse left; worn (C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 7.

2 / A.S.B. / AE 56-8 -65 / Similar; not quite complete. / Ditto; ditto.

3 / A.S.B. / AE 54-3 -73 / Ditto ; ditto; also a tree-like symbol below legend. / Ditto; horse well preserved.

4 / I.M. / AE 84 -7 / Ditto; ditto; ditto. / Ditto; worn.

5 / I.M. / AE 60 -73 / Ditto; ditto; ditto. / Ditto.

6 / I.M. / AE 28 -65 Ditto; defaced, only Khatapa legible / Horse r., with man in front; thin coin.

HAGAMASHA ALONE 1 / I.M. / AE 91-3 -77 / Figure standing on pedestal, nearly as on coins of the Rajas; tree-like symbol in r. field. Marginal Br. legend, Khatapasa Hagamashasa, ‘[Coin] of the satrap Hagamisha.’ / / Horse l. (C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 6).

2 / A.S.B. / AE 64-5 -67 / Similar; legend incomplete. / Ditto.

3. A.S.B. / AE 74-3 -77 / Similar; much damaged. / Ditto; worn.

4. A.S.B. / AE 76-3 -8 / Ditto; ditto / Ditto; ditto.

5 / I.M. / AE 19-7 -65 / Ditto; traces of legend, thunderbolt r. / Ditto; ditto; thin coin (may belong to Hagana and Hagamasha).

6 / I.M. / AE 59-7 / Similar to No. 1; damaged / As No.1; worn.

7 / I.M. / AE 74-1 -72 / Ditto; ditto. / Ditto; horse r.

8 / I.M. / AE 57 -85 / Ditto; legend almost complete. / Ditto; horse l.

9 / I.M. / AE 45-2 -8 / Ditto; -tapasa legible. / Ditto; horse r.

10 / A.S.B./ AE brass 44-5 -63 / Ditto; -gamasha legible. / Ditto; ditto.

RANJUBULA (RAJUVULA), ABOUT 110 B.C. Silver, base 1 / I.M. / AE 38-5 -58 / Head of satrap diad. r., as on coins of Strato II; corrupt Greek legend. / Pallas l., holding aegis in l. hand, hurling thunderbolt with r. Kh. legend, mahachatrapasa, and ha in l. field; name lost (C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 2,3, J.R.A.S., 1894, p. 547, fig. 2, 3).

2 / I.M. / AE 34 -53 / Ditto. / Ditto; ditto; character in r. field.

Copper (bronze) 3 / I.M. / AE 45-3 -62 / Standing female, as on coins of the Rajas, Br. marginal legend, [Mahakhatapasa] Rajuvulusa, [Coin] of the great satrap Rajuvula.’ / Defaced (C.A.I., P1.VIII, 4; J.R.A.S., ut sup., fig. 4).

SODASA, SON OF RANJUBULA Copper (bronze) 1 / A.S.B. / AE 24-5 -58 / Standing female and tree-like symbol r., as on coins of the Rajas. Br. marginal legend, [Mahakhatapasa putasa khatapasa So]da-sasa; ‘[Coin] of the satrap S., son of the great satrap.’ / Defaced; traces of Lakshmi and elephants (C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 5; J.R.A.S., ut sup., fig. 5, 6).

2 / A.S.B. / AE 29 -63 / Similar; dasasa legible svastika at end of legend. / Ditto.

3 / A.S.B. / AE 98-8 -7 / Similar; mahakhatapasa legible. / Lakshmi with elephants pouring water over her (Pl. XXII. 13).

4 / A.S.B. / AE 74-5 -75 / Similar; khatapasa putasa khatapasa So. / Ditto; nearly defaced.

5 / I.M. / AE 49-4 -63 / Standing female as usual. Br. legend arranged parallel to figure, r., khatapasa; l., [So]dasasa. / Ditto; very rude (unpublished variety of obv.).

6 / I.M. / AE 45 -7 / Standing female as usnal./ Marginal legend, Khatapasa (Sodasasa).1 / Defaced.

VIRASENA, A KING IN THE GANGETIC DOAB, (?) ABOUT 300 A.D.

Copper, rectangular, die-struck 1 / I.M. / AE 29 -6 / Virasena in early Br. script, in shallow incuse at top; rest blank. / (?) an animal; worn (Pl. XXII, 14).

2 / A.S.B, / AE 34 -6 / Ditto; worn. / Apparently the hind part of a bull.

3 / I.M. / AE 22 -42 / senasa only in shallow incuse at top; rest blank. / Apparently blank; (resembles some Malava coins). 2

4 / A.S.B./ AE 32-8 -65 / Above, V[ i]rasenasa; below, palm-treé and ornaments. / Rude standing figure; r. hand raised, l, hand on hip; worn (C.A.I., Pl. VIII, 18).

5 / I.M. / AE 24-2 -52 x -45 / Similar / Rude sketch of standing female, with rayed crown (Pl. XXII, 15).

6 / A.S.B./ AE 28-7 -5 x -45 / Similar; a senasa. / Apparently blank.

7 / I.M. / AE 19-7 -46 / Similar; Virasenasa. / Rude female figure, apparently seated l.

8 / I.M. / AE 14.5 -45 / Ditto; ditto. / Indication of crowned female.

9 / A.S.B./ AE 24-1 -45 / Ditto; ra senasa. / Ditto.

10 / I.M. / AE 21.3 -45 x -4 / Ditto; Virasenasa; the ornaments at lower corners are a form of ‘taurine’. / Ditto.

11 / A.S.B./ AE 21 -45 / Ditto; ra senasa. / Almost defaced.

12 / I.M. / AE 21-3 -45 x -4 / Ditto; Virasena. / Indication of crowned female.

13 / I.M. / AE 20-7 -47 / Ditto; V[ i]ras[e]nasa. / Ditto.

14 / I.M. / AE 22 -45 / Ditto; s[e]nasa, / Ditto. +45

1 On these coins Khatapasa may be read as Khatrapasa.

2 Nos. 1-3, as remarked in the Introduction, may be of earlier date than the others.

19-21 ReferencesSECTION X: UNASSIGNED MISCELLANEOUS ANCIENT COINS OF NORTHERN INDIA

INTRODUCTION The simple process of making coins by casting in a mould seems to be little inferior in antiquity in India to that of stamping bars or ingots. Comparatively few of the numerous cast coins of ancient India are blank on the reverse. Most of them have a device or legend, or both, on each face, and were made by joining two moulds together. All the cast coins are of copper, including in that term various alloys. The most ancient examples probably are to be found among the rude pieces which are abundant in Oudh, Benares, and the neighbouring districts.

Cunningham considered the chaitya and tree coin of C.A.I., Pl. 1, 29, to be ‘rather rare’; but I should be disposed to call it ‘rather common’. Six examples of it have been catalogued, ranging in weight from 27-5 to 61 grains. No. 16 with the legend Kumhama is novel, and I cannot explain the meaning of the word. No. 19 is the largest rectangular cast coin that I have seen.

The circular cast coins, no doubt, were, to a large extent, contemporary with the rectangular ones. The types ‘chaitya and elephant’ and ‘chaitya and bull’ served as models for the much improved anonymous coins struck by some of the Western Satraps between 225 and 236 A.D. (C.M.I, p. 7, with correction of date of No. 10 from 129 to 158, Rapson); and this fact helps us to fix a posterior limit for the cast coinage in Ujjain and the neighbourhood. Of course, in different parts of India the practice varied greatly, and the old-fashioned methods of coining must have lingered in some places longer than in others; but in the Panjab and upper Gangetic provinces the cast coins are, I should think, probably all earlier than 100 A.D. They must have been driven out of circulation largely by the abundant copper issues of the Kushan kings. In Malwa (Avanti, Ujjain), as remarked above, the cast coinage may have lasted until 200 A.D., or even a little later.

The anonymous coins apparently die-struck include one silver specimen of minute size. The rest are all copper or brass. The metal has not been analysed, and by ‘brass’ I mean an alloy that looks like brass—it may be a pale bronze. The lead coins, Nos. 15-21, ranging in weight from 43-5 to 68-2 grains, are too rude to admit of exact description or reproduction. There is nothing to indicate their age. Some specimens formerly in my cabinet were believed to come from the ancient site Atranji Khera in the Etah (Ita) District, U.P. Those catalogued may come from the same place, which was inspected by Cunningham ‘Reports, i. 269; xi. 15).

The inscribed circular coins, mostly die-struck (class IV), comprise many remarkable pieces, some of whish seam to be unpublished. The script on the coins of Brahmamitra and Gomitra (Nos. 1, 2), appears to be nearly, if not quite, as old as that of the Asoka edicts. The names recur in the series of the Rajas of Mathura (ante, Sect. IX) at a later date.

Carlleyle ‘picked up’ a specimen of Jyeshthadattadeva’s coinage at the extremely ancient site of Bairint in the Benares District (Reports, xxii. 15), which may be the coin catalogued (No. 3). I do not know of any other specimen. The coin (No. 4) on which I read Kavirasa jaya, with jaya written reversed, also appears to be unique. Other examples of reversed legends occur in the Malava class (ante, Sect. VII). The little piece (No. 17) with blank rev. and Depha on obv. is very curious, and I cannot guess the meaning of the word. The Devasa class (separately numbered) is puzzling. The coins are common in the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, and a good specimen which I formerly possessed came from Kosam in the Allahabad District. The upper characters look like numerals in the old notation. The reading devasa is due to Prof. Rapson. The first character, being peculiar in form, has been read generally as Ne, but De appears to be the correct reading. There is nothing to indicate who Deva was.

CATALOGUE

I. RECTANGULAR CAST COINS, EARLY

Serial No. / Museum / Metal, Weight, Size / Obverse / Reverse

Copper

(1) AS C.A.I., Pl. I, 28 1/ I.M. / AE 59-7 -6] Tree in railing: chaitya; square cross; and a form of 'taurine'. / Elephant l.; triangular-headed symbol; ‘taurine’ (PL. XXII, 16).

2. I.M. / AE 64 -58 / Similar. / Similar.

3 / I.M. / AE 41 -58 / Similar to No. 1. / As No.1; with svastika.4 / AS.B. / AE 62-5 -65 / Ditto. / Elephant l.; square cross; triangular-headed symbol.

5 / I.M. / AE -- -58 / Ditto; worn. / As No. 3, but differently arranged: a protuberance left in casting.

6 / A.S.B./ AE -- -6 / Ditto; ditto. / Similar; with bar -37 long attached.

7 / A.S.B. / AE -- -57 / Ditto; fairly good. / Ditto; with protuberance.

8 / A.S.B. / AE 29-6 -5 / Ditto; corroded. / Ditto; corroded.

9 / A.S.B. / AE 13 -37 / Ditto; ditto. / Ditto; ditto.

(2) AS C.A.I., Pl. I, 29 10 / I.M. / AE -- -55 / Tree with ovate-lanceolate leaves / Chaitya of three arches, with crescent above; protuberance from casting,

11 / I.M. / AE 58 -5 / Ditto. / Ditto (Pl. XXII, 17).

12 / I.M. / AE 61 -5 / Ditto. / Ditto.

13 / I.M. / AE 53-2 -55 / Ditto. / Ditto.

14 / A.S.B. / AE 56-3 -5 / Ditto. / Ditto.

15 / I.M. / AE 27-5 -45 / Ditto. / Ditto.

(3) VARIOUS

a. Inscribed 16 / I.M. / AE 40 -57 x -45 / Tree l. Legend in large letters Kunhama, with apparently ya above. / A (?) tiger springing l. (Pl. XXII, 18).

17 / I.M. / AE 9-4 -45 / Snake below; obscure symbols, and remains of legend including yo. / Elephant l., and (?) tree; thin coin, probably from eastern districts.

18 / I.M. / AE 16-7 -5 x -42 / Solar symbol; traces of legend / Humped bull l.

18a / A.S.B. / AE -- hexagonal -55 / Elephant l; above, Br. legend, bhaga ... / Tree and (?).

b. Not inscribed 19 / A.S.B./ AE 139-6 1-1 / Humped bull standing l in a square; row of symbols above, svastika, &c. / Circle inside square, containing vase on stand with streamers and (?) flowers. Remarkable for large size (Pl. XXII, 19).

20 / I.M. / AE 118-3 -7 x -55 / Lion or tiger l., facing a bunch of three stems (? fire) springing from the ground, and beyond it the triangular-headed symbol common on ancient coins. / Blank.

21 / I.M. / AE 72-7 -52 / Humped bull l,, with crescent in front. / Ditto.

22 / I.M. / AE 80-6 -5 x -5 / Similar to No. 21, but no distinct objects in front of animal. / Ditto.

23 / I.M. / AE 23-8 -4 x -35 / A sort of ‘taurine’ in high relief. / Ditto.

24 / I.M. / AE 24-3 -4 / Ditto. / Ditto.

25 / I.M. / AE 18 -37 x -32 / Ditto / Ditto (These three coins have a button of metal from the casting at the back.)

26 / I.M. / AE 19-7 -30 / Rude human figure l. with r. hand raised; (?) traces of legend r. / Two pellets in relief (possibly Malava; Pl. XXIII, 1).

27 / A.S.B. / AE 38-5 -7 / Obscure symbols in a curved frame. / Obscure symbols with long straight lines.

28 / I.M. / AE 52-8 -6 / Tree in railing, in circle of which a snake is the base. / Elephant l., facing a symbol.

29 / I.M. / AE 35 -5 / Square cross. / Elephant r.

30 / I.M. / AE 21-7 -5 / Ditto. / Ditto.

31 / A.S.B. / AE -- -58 / Three-arched chaitya, crescent above. / Elephant l.; corroded.

32 / I.M. / AE brass 60-7 -65 / Three-arched chaitya, with crescent above, standing under an arch. / Humped bull r. with tail raised, and feet tied together, facing a railing with (?) tree in it, on which (?) a bird pecking the bull (Pl. XXIII, 2).

33 / I.M. / AE 15 -45 / Tree in railing; St. Andrew’s cross with balls at ends of arms; square cross. / Humped bull l.; svastika above.

34 / I.M. / AE 6-8 -45 / Similar, but partly defaced. / Similar, but mostly defaced.

35 / I.M. / AE 23-7 -47 / Ditto; ditto. / Ditto; fairly good; an object before bull.

36 / A.S.B. / AE 45-5 -5 / Solar symbol composed of ‘taurines’ and broad arrow-heads attached to central boss. / Svastika opening to r.

37 / A.S.B. / AE 30-5 -5 / Sundry indescribable symbols. / Svatika opening r., with 'taurines' at the extremities.

38 / A.S.B. / AE 47 -5 / Ditto. / Ditto; thick coin (Nos. 36038 are in very shallow relief).

39 / A.S.B. / AE 15-5 -36 / Indistinct marks. / incised rectangle. (Perhaps should be classed as 'punch-marked'.

40 / I.M. / AE 54-5 -67 x -5 / Rude solar symbol of boss and crescents. / Blank; very rough.

41 / A.S.B. / AE 13-6 -64 x -4 / Lion standing l., facing tree; svastika above. / Elephant l., facing post; doubtful traces of legend above; (?) Taxila; thin coin.

II. ANONYMOUS CIRCULAR CAST COINS, PROBABLY ALL BEFORE 200 A.D.

Copper

(1) Chaitya and elephant type (C.A.I., Pl. 1, 25) [/b]

1 / I.M. / AE 47 -55 / Three-arched chaitya, with crescent above. / Elephant l.

2 / I.M. / AE 33-7 -55 / Ditto. / Ditto.

3 / A.S.B. / AE 37-3 -55 / Ditto. / Ditto.

4 / A.S.B. / AE 34 -55 / Ditto. / Ditto.

5 / A.S.B. / AE 28-8 -52 / Ditto. / Ditto.

6 / I.M. / AE 13-6 -47 / Ditto. / Ditto (Pl. XXIII, 3).

7 / I.M. / AE -- -5 / Ditto. / Ditto; two coins joined by bar left in casting.

8 / I.M. / AE 26 -55 / Ditto. / Elephant r.

(2) Chaitya and bull type (C.A.I., Pl. I, 26) 9 / I.M. / AE 63 -65 / Three-arched chaitya, with crescent above; a ‘taurine’ symbol on each side. / Large-horned bull r.; triskelis above.

(3) Chaitya and lion type (C.A.I., Pl. I, 27) 10 / I.M. / AE 63-8 -6 / Three-arched chaitya, with crescent and ‘taurines’, as in bull type. / Lion moving l. towards triangular-headed symbol.

11 / I.M. / AE 67-1 -57 / Ditto. / Ditto.

12 / I.M. / AE 73-2 -57 / Ditto. / Ditto.

13 / I.M. / AE 53 -57 / Ditto / Ditto.

14 / I.M. / AE 16-8 -45 / Ditto. / Ditto.

15 / I.M. / AE 23-5 -53 / Ditto. / Lion r.

(4) Various 16 / A.S.B./ AE 91 -7 / Rayed sun. / Quadruped l.; much worn.

17 / A.S.B. / AE 68 -65 / Ditto. / Quadruped r.; ditto.

18 / I.M. / AE 37-5 -55 / Six-spoked wheel. / Obscure.

19 / I.M. / AE brass 66 -76 / Rayed sun above low enclosure. / Bull r.; very rough.

20 / I.M. / AE 64 -7 / Tree in railing; square cross, &c. / Elephant l.; solar symbol; chaitya, and triangular-headed symbol.

21 / A.S.B./ AE 14 -47 / Tree in railing, as on coins of Kosam; ‘Ujjain symbol’ r. / Blank.

22 / A.S.B. / AE 27-7 -55 / Humped bull l. / (?) Antelope r.; corroded.

23 / I.M. / AE 23-8 -47 / Three-arched chaitya. / Quadruped l.

24 / I.M. oval 29-3 -75 x -5 / A curious object in high relief. / (?) Bull’s face (Pl. XXIII, 4).

III. APPARENTLY DIE-STRUCK, NOT INSCRIBED [ Silver 1 / I.M. / AE 22-7 -4 / Quadruped (? horse) r. / Blank.

Copper or brass 2 / A.5.B./ AE square 58-3 -67 / Solar symbol consisting of boss with broad arrowheads and crescents, in incuse made by circular die. / Svastika with curved limbs (? Ujjain).

3 / I.M. /AE square 17 -42 / ‘Ujjain symbol’ of four circles without connecting cross; (?) lion; struck by circular die. / Quadruped l., facing a post (? Ujjain).

4 / I.M. / AE 14 -42 / Three-arched chaitya with crescent . / 'Taurine' (seems to be die struck).

5 / A.S.B. / AE 71-8 -78 / 'Taurine' in small incuse; rest blank. / Apparently blank; worn.

6 / I.M. / AE hexagonal 47-2 -87 / cup-mark surrounded by six others similar. / Apparently blank.

7 / I.M. / AE hexagonal 60-8 -75 / Ditto. / Ditto.

8 / I.M. / AE hexagonal 17-5 -35 x -45 / Similar, with incised rays connecting the marks. / Ditto.

9 / I.M. / AE 49-5 -73 / Trident with curved sides. / Cross in wheel (?Taxila).

10 / I.M. / AE 27-9 -67 / Similar. / Star with curved rays filling the field (? Taxila); worn.

11 / A.S.B. / AE brass 45-2 -7 / Sun with numerous rays filling the field. / Same as obv.; (?) traces of legend; worn smooth.

12 / I.M. / AE 85-5 -85 / Lion standing r. / Humped bull standing r.; worn.

13 / I.M. / AE 32 -62 / Tree in railing; 'taurine', &c. / Elephant moving r. (? Audumbara).

14 / I.M. / AE 67-7 -7 / Elphant r., very rude. / Obscure lines; worn.

Lead15 / I.M. / L. 56 -54 / Convex, with obscure indescribable mark. / Flat, with obscure lines.

16 / I.M. / L. 63-2 -58 / Similar. / Similar.

17 / I.M. / L. 60-5 -55 / Ditto. / Ditto.

18 / I.M. / L. 54-5 -55 / Ditto. / Ditto.

19 / I.M. / L. 47 -57 / Ditto. / Ditto.

20. /I.M. / L. 53 -52 / Ditto. / Ditto.

21 / I.M. / L. 43-5 -45 / Ditto. / Ditto.

IV. INSCRIBED, CIRCULAR, VARIOUS,

MOSTLY DIE-STRUCK

Copper or brass

(1) Various1 / A.S.B. / AE 84-5 -7 / In circular incuse, tree in railing, triangular-headed symbol r. ; ‘Ujjain symbol’; below in Br. of about 200 B.C. Brahma-mitasa, ‘[Coin] of Brahmamitra.’ / Tree-like symbol in railing; (?) Kosam (Pl. XXIII, 5).

2 / A.S.B. / AE brass 64 -77 / In square incuse, tree in railing l.; ‘Ujjain symbol’ in centre; triangular-headed symbol r.; below in Br. of about 200 B.C. (Go)mitasa, ‘[Coin] of Gomitra.’ / Tree in railing and traces of Br. legend beginning with Gomi in shallow squre incuse; allied to No. 1 (Pl. XXIII,, 6).

3 / I.M. / AE 32-5 -6 / In oblong incuse, early Br. legend, Jyeshthadattade[va], or possibly, datta-sya. / Traces of elephant standing r.; resembles some of the early Malava coins; see Reports, XXII, 115 (Pl. XXIII, 7).

4 / A.S.B. / AE 50-8 -75 / Humped bull standing r.; below, early Br. legend, Kavirasa; below, jaya, reversed; and (?)a character; ‘Victory to Kavira’: raised rim. / Defaced (unpublished) (Pl. XXIII, 8).

5 / A.S.B. / AE brass 81-3 -65 / Solar symbol, two trees in railings, ‘Ujjain symbol,’ &c.; above in early Br., mitasa or shatasa. / Open lotus flower; thick coin.

6 / I.M. / AE 24 -45 / Tree in railing; snake on end, r. / Bull l. (? Kosam or Ajodhya).

7 / A.S.B. / AE 24-4 -52 / Peculiar object springing from railing; Br. na r. / Asokan ja (?) (Pl. XXIII, 9).

8 / A.S.B. / AE oval 71-7 -85 x -75 / Tree in railing and other obscure symbols; Br. legend l., apparently chija. / Lion r.; railing above, and traces of marginal Br. legend (Pl. XXIII, 10).

9 / A.S.B. / AE 3-7 -35 / Large characters, which look like charéja, or charaju. / Br. la in centre of field (Pl. XXIII, 11).

10 / A.S.B. / AE 61-7 -53 / In circular incuse, tree in railing; obscure Br. marginal legend including yana, (?) traya nagasa. / Lion standing r.; disk above.

11 / A.S.B. / AE 53-1 -55 / Similar to No. 10. Legend, ratha yana-gicha-m[ i]ta[sa] (?). / Lion standing r.; squre (? ba) over his back; marginal legend in large character, ya (Pl. XXIII, 12).

12 / I.M. / AE 24-3 -55 / Tree in railing l.; thunderbolt (vajra) r.; traces of marginal legend. / Tree in railing, and obscure symbols; marginal Br. legend, (?)gabhemanapa (or -ha), of which bha and na are certain (Pl. XXIII, 13).

13 / I.M. / AE imperfect -5 / Thunderbolt (vajra) in centre, standing figure r.; Br. legend l., (?) mabhada, or (?) mitasa. / Peculiar symbol (Pl. XXIII, 14).

14 / I.M. / AE oval 15-9 -6 x -5 / Tree in railing; Br. na legible. / Three-arched chaitya with large ornament on top.

15 / A.S.B. / AE 17 -47 / Peculiar symbol; traces of Br. marginal legend. / Bull standing l.; thin coin; worn.

16 / I.M. / AE 24-7 -45 / Bull l.; traces of legend below. / Obscure symbol.

17 / I.M. / AE 17-3 -4 / Depha in large early Br., filling field, [x]; worn. / Blank (? Malava).

18 / I.M. / AE 22 -4 / Uncertain large characters. / Quadruped l.; corroded.

19 / I.M. / AE 20-5 -57 / Branching tree in railing; to l., early Br. napa (or -sa). / Obscure, (?) lion r.; thin coin, possibly Audumbara; in bad condition.

20 / I.M. / AE 20 -37 / Uncertain. / Uncertain (antiquity doubtful).

(2) With legend, DEVASA, probably of Kosam1 / I.M. / AE brass 29-7 -55 / Tree in railing, as on Kosam coins; below, in early Br., [De]vasa; l. of tree a character, seemingly the ancient 20, and r., 7; all in square incuse. / Rude bull, apparently l.; probably cast (Pl. XXIII, 15).

2 / I.M. / AE brass 20 -5 / Similar; but the figure to l. of tree is looped, and seems to be 6; all in incuse. / Bull r.; cast.

3 / I.M. AE brass 35-6 -6 / Similar; no figure to r.; that 1. seems to be 20 as on No. 1; legend imperfect. / Ditto.

4 / I.M. / AE brass 26 -46 / Ditto; ditto; Deva. / Elephant standing r. (Pl. XXIII, 16).

5 / I.M. / AE brass 16-5 -45 / Ditto; characters beside tree illegible; Devasa; no incuse. / Bull r.; defaced.

6 / A.S.B. / AE brass 64-8 -76 / Square frame with low railing as base, enclosing legend Devasa in large letters, and above, an altar-like object. / Ditto; uncertain object above; worn smooth on both sides.

7 / A.S.B. / AE brass 74 -67 / Similar; legend mostly lost; a stumpy tree above; the figure 7 to r., figure to l. wanting. / Bull r.; protuberance left in casting.

8 / A.S.B. / AE brass 68-5 -67 / Ditto; ditto; ditto. / Bull r.; five-branched object (? tree) above; hammered edges apparently.

22-25 ReferencesBhavadatta, r., pp. 190, 193...

Purushadatta, r., pp. 190-192...

Sivadatta, r., pp. 144, 149...

Uttamadatta, r., pp. 190,193..

26-29 ReferencesSECTION XX. THE NORTH-EASTERN FRONTIER KINGDOMS; ASSAM AND MINOR STATES

INTRODUCTIONIt is unnecessary to discuss in this place the meagre data available for the reconstruction of the ancient history of the kingdom of Kamarupa, which corresponded roughly with the modern province of Assam (Asam). The early rulers of the country have not left any numismatic memorials. The modern history of Assam begins with the invasion of the Ahoms, who are ‘the descendants of those Shans who, under the leadership of Chukapha, crossed the Patkoi [mountains] about 1228 A.D. (or just about the time when Kublai Khan was establishing his power in China) and entered the upper portion of the province, to which they have given their name. The Ahoms were not apparently a very large tribe, and they consequently took some time to consolidate their power in Upper Assam. They were engaged for several hundred years in conflict with the Chutiyas and Kacharis, and it was not till 1540 A.D. that they finally overthrew the latter, and established their rule as far as the Kallang [river near Gauhati]. . . . Subsequently the Koch kingdom [further west] was divided into two parts, and as its power declined that of the Ahoms increased, and the Rajas of Jaintia, Dimarua, and others, who had formerly been feudatories of Biswa Singh, acknowledged the suzerainty of the Ahoms, The Musalmans on several occasions invaded their country, but never succeeded in permanently annexing it.... In 1663 A.D. Mir Jumla invaded the country with a large army, and after some fighting took the capital. [But difficulties ensued, which made] him ‘glad to patch up a peace..... The Ahoms then took Gauhati and ... defeated another Musalmain army. The Ahoms were then [about 1670 A.D.] at the height of their power; all the minor rulers of the country acknowledged their supremacy. ... But even then the decline was at hand. They had for some time hankered after Hinduism, and the Rajas had for years been in the habit of taking a Hindu as well as a Shan name. Eventually Rudra Singh, alias Chukrungpha, who became king in 1695, [and is regarded by many as the greatest of all the Ahom kings] resolved to make a public profession of Hinduism, ... but died in 1714 while still unconverted. His son, Sib Singh [Siva sinha], succeeded him, and became a disciple of Krishna-ram [the Sakta Gosain of Nadia]. In his reign the seeds of future dissensions were sown by the persecution of the Moamarias, while the pride of race, which had hitherto sustained the Ahoms, began to disappear.... Patriotic feeling soon disappeared, and the country was filled with dissensions.... Captain Welsh was deputed by Lord Cornwallis to help the King Gauri-nath Singh, who was then being besieged at Gauhati, and with his aid he was once more freed from his enemies. At this juncture Sir John Shore succeeded to the Governor-Generalship, and one of his first acts was to recall Welsh (1794 A.D.), after whose departure the country was given again over to anarchy. The aid of the Burmese was then invoked (1816 A.D.), and the latter remained in the country until 1824, when they were driven out by our troops, and the country was annexed’ [early in 1825].1 [

Grierson (quoting Gait), Linguistic Survey of India, vol. ii, p. 61, with additions in brackets.] An Ahom Raja however continued to exist for some time longer, and in 1844 the last of the royal line did good service by arranging for the publication of a history of his country, which had always been careful to preserve its annals.

The foregoing summary of the history will serve, with little additional explanation, to render intelligible the fine series of coins now catalogued. A list of the Rajas will be found in Prinsep’s Useful Tables, copied into Duff's Chronology of India, and corrected by Gait (Report on the Progress of Historical Research in Assam, Shillong, Secretariat Printing Office, 1897). The blue-book last named gives complete references to all publications on the subject of Assamese history, which has recently been treated in detail by Mr. Gait in his work entitled A History of Assam (Calcutta, Thacker Spink, 1905), which also deals with the neighbouring minor states.

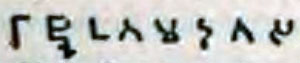

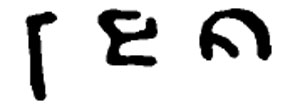

The initial syllable of the Shan names of the kings is generally given as Chu, but Babu Golap Chandra Barua, the Ahom translator, transliterates it as Su ([x]) in his account of the Ahom coins (J.A.S.B., Part I, 1895, p. 286, Pl. XXVII). The six coins described by the Babu and Mr. Gait are all included in this catalogue, with the addition of two specimens of Supatpha or Gadadhar simha from the Indian Museum cabinet.

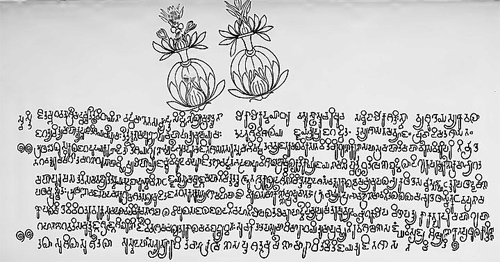

The earlier Rajas seem to have issued coins inscribed with legends in the Ahom language and character only, but Raja Pramatha simha, alias Sunenpha, used both Ahom and Sanskrit. The catalogue includes one of his coins with Ahom and eight with Sanskrit legends. The Ahom language, which is now almost extinct, is a member of the group of Northern Shan (Sham or Tai) languages, and is written in a peculiar character, ultimately derived from the Pali. In the work above cited Dr. Grierson has supplied ample materials for the study of the Ahom language and alphabet, but his vocabulary fails to include the words in the coin legends. The readings of those legends in the catalogue are given on the authority of Babu Golap Chandra Barua.

The coins of the dynasty are all octagonal, except a few of the smallest, which are circular or oval,1 [The prevailing shape is supposed to have been suggested by a statement in the Jogini Tantra which describes the Ahom country as octagonal (Gait, History, p. 97).] and certain square pieces struck by Queen Pramathesvari and Rajesvara simha, which bear Persian legends. Rajesvara simha also struck coins of the usual octagonal shape with Persian legends. These Assamese coins with Persian legends, although struck in considerable numbers, have become known only recently.2 [Mr. H.N. Wright kindly examined the coins with Persian legends, which were received in May, 1906.] The larger pieces are of thick, solid fabric, and are said to be of good metal. Most of them are in silver, but some are gold. The legends are well executed, and those in the Sanskrit language usually are inscribed in the Bengali script. They are intensely devotional in expression, the commonest formula describing the Raja as a bee feeding on the nectar from the feet of Siva or some other deity of the Hindu pantheon. Poetical words, such as aravinda for ‘lotus’ and makaranda for ‘nectar’, are sometimes substituted for the more common equivalents kamala and amrita. The Ahom legends of Supatpha or Gadadhar sitha express devotion to the tribal god Leidan, who was identified with the Hindu Indra or Purandara. The legend on the coin of Suklenmun represents the Raja as praying to the Almighty (tara). The coins, the heaviest of which weighs 176-7 grains, appear to be intended for rupees of about 175 grains each, or for fractions of a rupee. The smallest is a tiny silver piece of Gaurinatha, -22 inch in diameter, and weighing only 4-2 grains; but small as it is, the Raja's name is distinctly legible (Pl. XXIX, 8). The gold coins are struck to the same weight standard as those in silver.

Most of the coins are dated in the Saka era, and some show the regnal year in addition. The coinage of the minor states may be dismissed briefly.

The small principality of Jayantapura, now known as the Jaintia Parganas to the north-east of the Sylhet District, was annexed in 1835 owing to the abduction of four British subjects for use as human sacrifices to Kali. Its rare coinage is represented by four specimens in the Indian Museum (Pl. XXIX, 13,14), one of which is dated in 1630 Saka = 1708 A,D., and the three others are dated 1653 S. = 1781 A.D. One duplicate of the latter date has not been catalogued. The coins are exceptionally broad, and bear legends similar to those of the Assamese coinage. Mr. Gait has recorded that ‘a number of new Jaintia coins were brought to light by Babu Giris Chandra Das, Assistant Settlement Officer of Jaintia, and a collection was made which has been presented to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The collection includes whole coins of Caka 1591, 1592, 1630, 1653, 1696, 1704, 1707, and 1712; and quarter coins of Caka 1653 and 1712: the quarter coins alone have the name of the kings who minted them, viz. Bara Gosain and Ram-sinha respectively. These coins have been described (with a plate) in the J.A.S.B. for 1895, Part I, p. 242’ (Report, p. 4). The paper referred to, entitled ‘Some Notes on Jaintia History’, and chapter XI of Mr. Gait’s History of Assam, give all the information available on the subject. The A.S.B. collection described by Mr. Gait has not been sent to me.

The Tipperah country (Tripura), which lies to the south of Sylhet and the east of Dacca, is now in part a British District, and in part a native state, known as Hill Tipperah. Mr. Gait (Report, p.4) mentions two coins of Tipperah, one of Govinda Manikya deva, dated Saka 1602, the other of Dharma Manikya deva, dated 1636. The latter was presented to the A.S.B. (Proc. 1895, p. 86), but has not come into my hands. The specimen now catalogued, struck by Ramasimha Manikya deva and his consort Tara, is new, but similar to the coins previously known. The reverse device is a grotesque lion with a trident on his back, and the date is 1728 S, = 1806 A.D.

The Manipur State, lying between Cachar and the Burmese frontier, was deprived of its independence in 1891 on account of the massacre of Mr. Quinton and his companions (Gait, History, p. 343). Some small copper coins with ma on the obverse, and the reverse blank, are ascribed to this State by Mr. Rodgers.

Chhota Udaipur is, I believe, part of Tipperah. The utterly barbarous copper coins assigned to it by Mr. Rodgers are undecipherable to me. The recent copper coins of the Sikim State to the north of Darjeeling are not in any way remarkable.

CATALOGUE

ASSAM (ASAM)

Serial No. / Museum / Metal, Weight, Size / Obverse / ReverseA. With legends in Ahom language and script; silver, octagonal ...

B. With legends in Sanskrit language and script; octagonal, except two coins ...

BHARATHA SIMHA, RAJA or Rangpur, 1792-3 A.D. AND AGAIN 1797 A.D.

Silver 1 / I.M. / AE 175-5 -95 / Four-line legend, (1) Sri Bhagadatta (2) kulodvara sri Bha (3) ratha simha nripasya (4) Sake 1714.1 [For legends of Bhagadatta (Bhagdatta) see Gait, History, pp. 13, 27, 29.] Dragon r. below. / Four-line legend, (1) Sri sri Krishna charanaravinda makaranda pramada madhukarasya; '[coin] of king Bharatha simha of the excellent lineage of Bhagadatta, intoxicated with the nectar of the lotus of the feet of Krishna, Saka 1714' = 1792-3 A.D. (Pl. XXIX, 9).2 / I.M. / AE 174-5 -87 / Ditto; date 1719=1797 A.D. / Ditto.

30-37 ReferencesGENERAL INDEX

ABBREVIATIONS

ci. = city or town; co. = country; d. = deity; dy. = dynasty; k. = king or chief; qu. = queen; ty. = type....Bhavadatta, k. of Mathura, 190, 198...

Kamadatta, k. of Mathura, 190...

Purushadatta, k. of Mathura, 190, 192...

Ramadatta, k. of Ajodhya, 190, 193...

Seshadatta, k. of Mathura, 190...

Sisuchandradatta, k. of Mathura, 190...

Sivadatta, k. of Ajodhya, 144, 149; k. of Mathura, 190...

Uttamadatta, k. of Mathura, 190, 198.