by Wikipedia

Accessed: 10/19/21

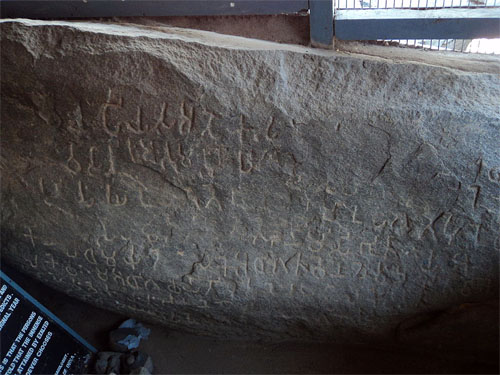

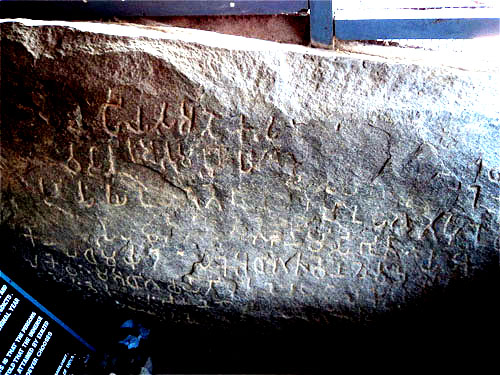

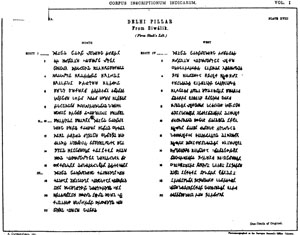

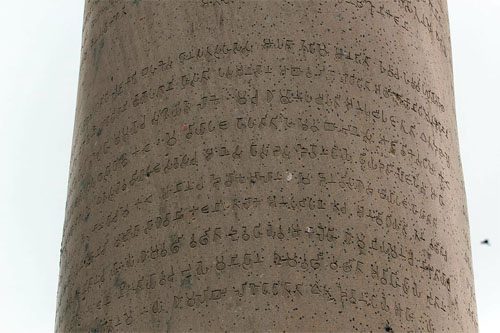

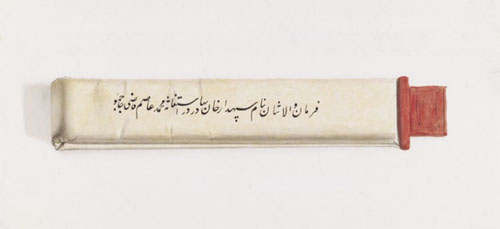

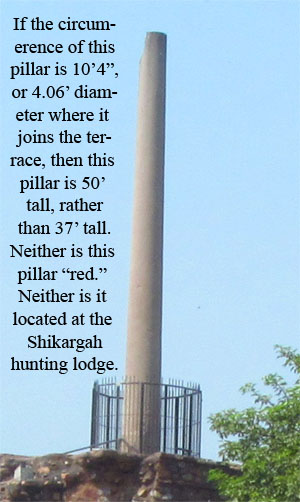

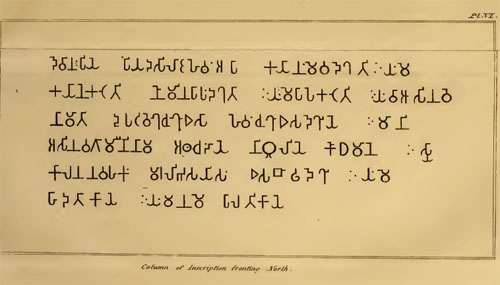

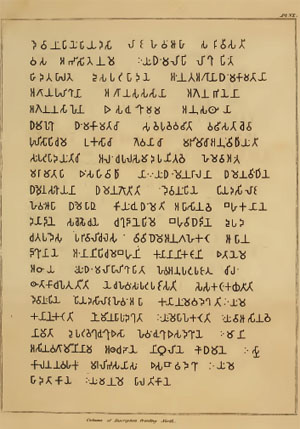

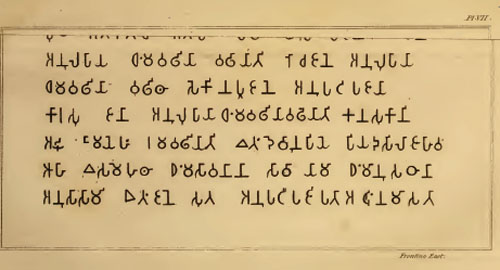

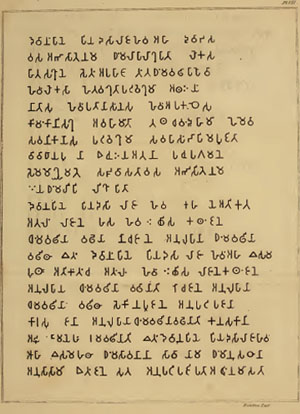

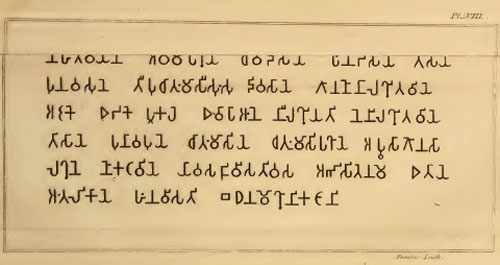

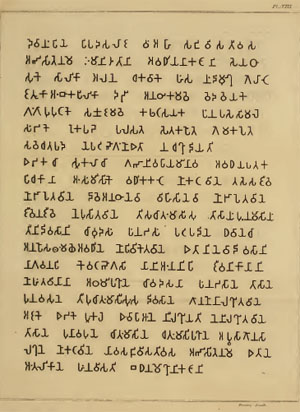

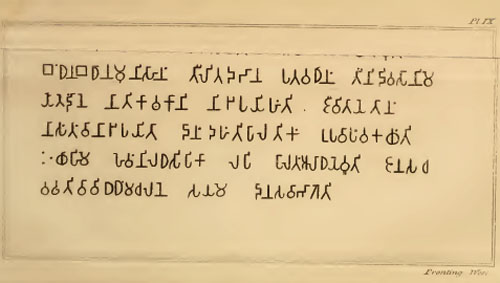

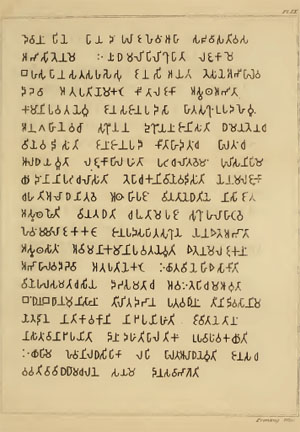

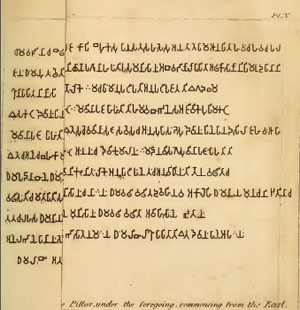

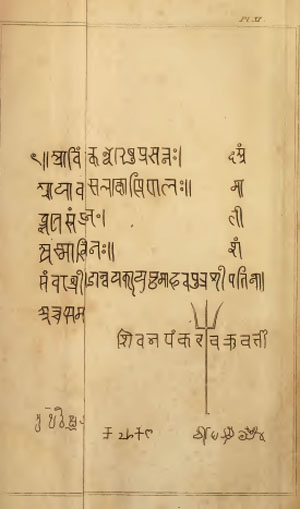

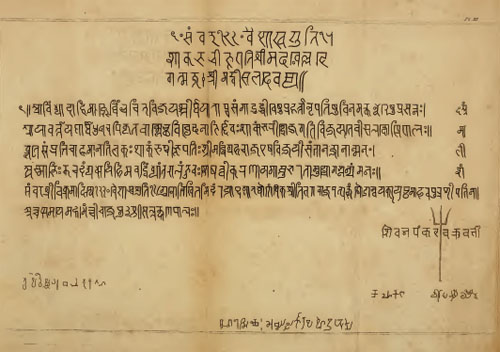

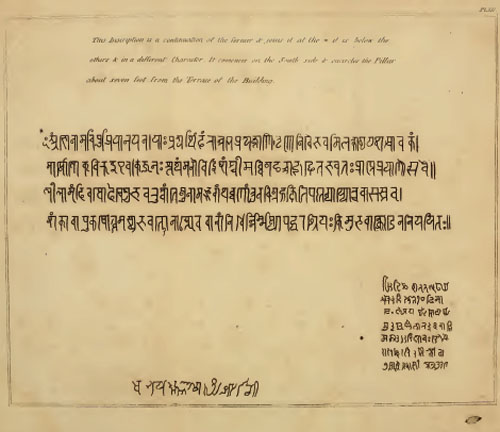

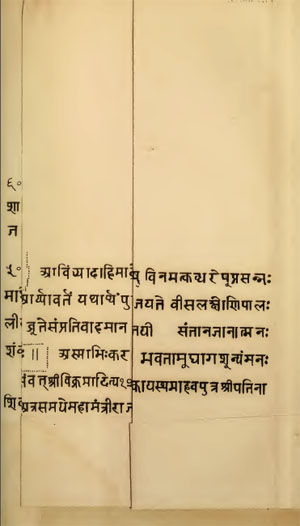

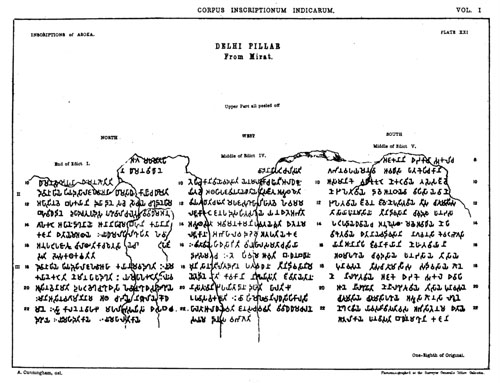

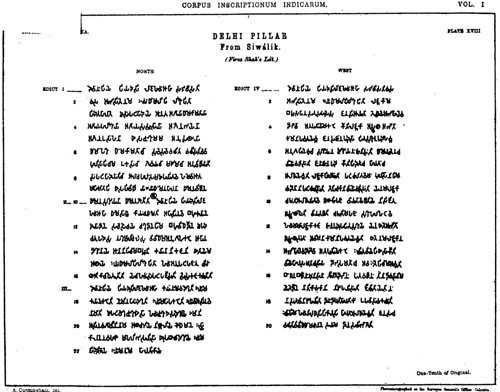

The Inscription fronting West.

1. Dewananpiya Pandu so raja hewan aha. "Sattawisati wasa

2. abhisitena me, iyan dhanmalipi likhapita. Rajjaka me

3. bahusu panasatasahasesu janesuayanti. Tesan yo abhipare

4. dandawe atapati, ye me kathi kin? Te rajjaka aswata abhita

5. kinmani, pawatayewun janasa janapadasa hitasukan rupadahewun;

6. anugahenewacha, sukhiyana dukhiyana janisanti; dhanmaya te nacha-

7. wiyewa disanti janan janapadan. Kin tehi attancha paratancha

8. aradhayewun? Te rajjaka parusata patacharitawe man purisanipime

9. * [The letter chh is read as r throughout; and the letter u as ru.— Ed.] rodhanani paticharisanti; tepi chakkena wiyowadisanti ye na me rajjaka

10. charanta arundhayitawe, athahi pajanwiya taye dhatiya nisijita;

11. aswatheratiwiya ta dhati, charanta me pajan sukhan parihathawe.

12. Hewan mama rajjaka kate, janapadasa pitasukhaye; yena ete abhita

13. aswatha satan awamana, kamani pawateyewuti. Etena me rajjakanan

14. abhikarawadandawe atapatiye katke, iritawyehi esakiti

15. wiyoharasamuticha siya. Dandasamatacha, awaitepicha, me awute,

16. bandhana budhanan manusanan tiritadandinan patawadhanan,tinidiwasani, me

17. Yutte dinne, nitikarikani niripayihantu, Jiwitaye tanan

18. nasantanwa niripayantu: danan dahantu: pahitakan rupawapanwa karontu.

19. Irichime hewan nira dhasipi karipiparatan aradhayewapi: janasacha

20. wadhati: wiwidhadanmacharane; sayame danasan wibhagoti." [By comparing this version with that published in July, it will be seen to what extent the license of altering letters has been exercised. The author has however since relinquished the change of the Raja's name, in consequence of his happy discovery of Piyadasi's identity.— Ed. (James Prinsep)]

-- Further notes on the inscriptions on the columns at Delhi, Allahabad, Betiah, &c., by the Hon'ble George Turnour, Esq. of the Ceylon Civil Service, 1837

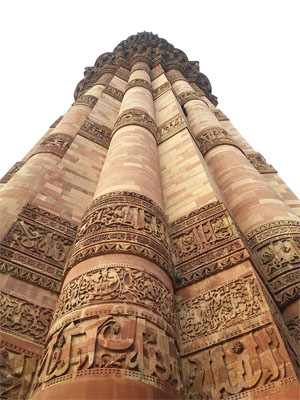

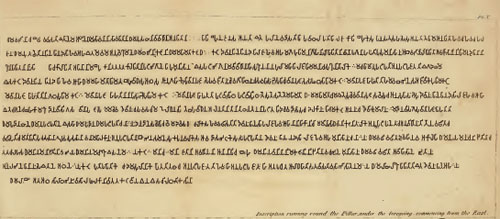

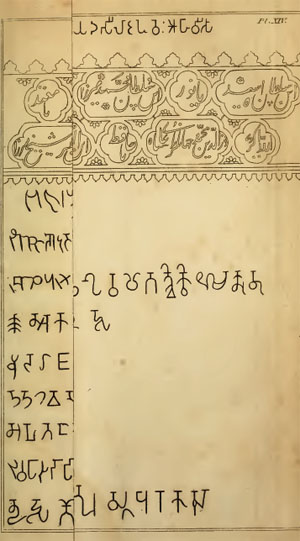

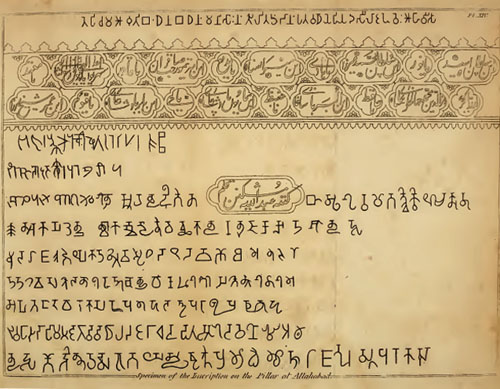

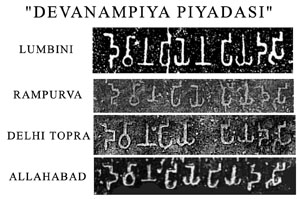

Various "Devanampiya Piyadasi" inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka.

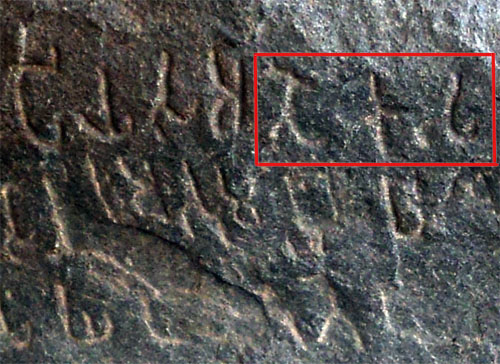

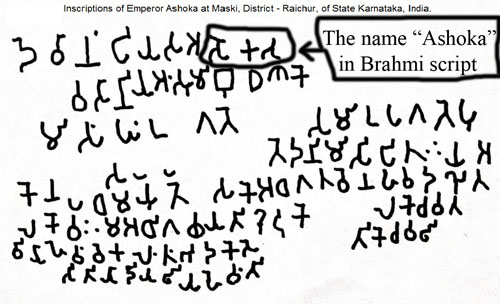

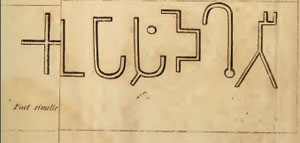

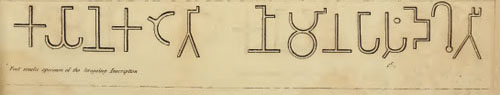

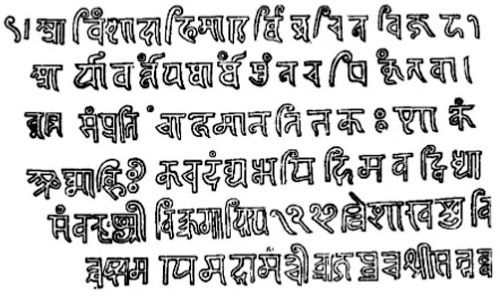

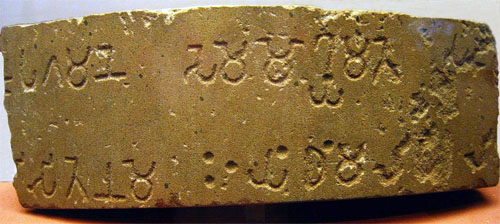

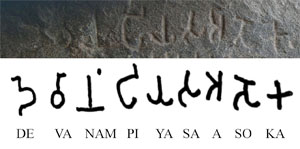

"Devānaṃpiyasa Asoka", honorific Devanampiya (Brahmi script: [x], "Beloved of the God", in the adjectival form -sa) and name of Ashoka, in Brahmi script, in the Maski Edict of Ashoka.

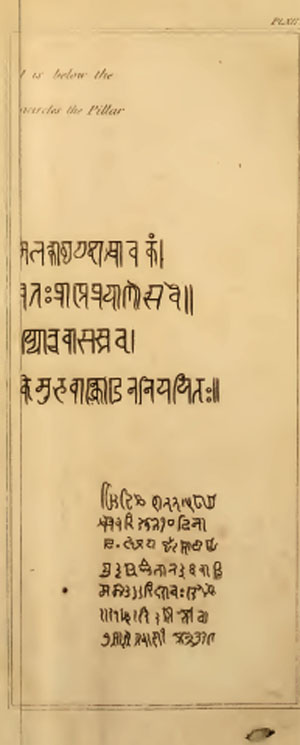

"Devānampiyena" ([x]:"Of Devanampiya") in the Lumbini Minor Pillar Edict of Ashoka. Brahmi script.

Devanampriya, also Devanampiya (Brahmi script: [x], Devānaṃpiya), was a Pali honorific epithet used by a few Indian monarchs, but most particularly the Indian Emperor Ashoka (r.269-233 BCE) in his inscriptions (the Edicts of Ashoka).[1] "Devanampriya" means "Beloved of the Gods". It is often used by Ashoka in conjunction with the title Priyadasi, which means "He who regards others with kindness", "Humane"[1]

The Kalsi version of the Major Rock Edict No.8 also uses the title "Devampriyas" to describe previous kings (whereas the other versions use the term "Kings"), suggesting that the title "Denampriya" had a rather wide usage and might just have meant "King".[2][3]

Prinsep in his study and decipherment of the Edicts of Ashoka had originally identified Devanampriya Priyadasi with the King of Ceylon Devanampiya Tissa of Anuradhapura.

But in my preceding notice, I trust that this point has been set at rest, and that it has been satisfactorily proved that the several pillars of Delhi, Allahabad, Mattiah and Radhia were erected under the orders of king Devanampiya Piyadasi of Ceylon, about three hundred years before the Christian era.

-- VI.—Interpretation of the most ancient of the inscriptions on the pillar called the lat of Feroz Shah, near Delhi, and of the Allahabad, Radhia [Lauriya-Araraj (Radiah)] and Mattiah [Lauriya-Nandangarh (Mathia)] pillar, or lat, inscriptions which agree therewit, by James Prinsep, Sec. As. Soc. &c.

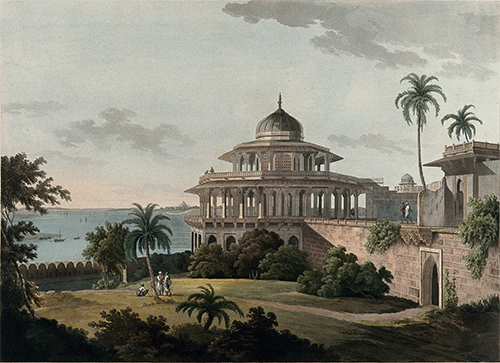

Tissa, later Devanampiya Tissa was one of the earliest kings of Sri Lanka based at the ancient capital of Anuradhapura from 247 BC to 207 BC. His reign was notable for the arrival of Buddhism in Sri Lanka under the aegis of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka. The primary source for his reign is the Mahavamsa, which in turn is based on the more ancient Dipavamsa.

Tissa was the second son of Mutasiva of Anuradhapura. The Mahavamsa describes him as being "foremost among all his brothers in virtue and intelligence".

The Mahavamsa mentions an early friendship with Ashoka. Chapter IX of the chronicle mentions that "the two monarchs, Devanampiyatissa and Dhammasoka, already had been friends a long time, though they had never seen each other", Dhammasoka being an alternate name for Ashoka. The chronicle also mentions Tissa sending gifts to the mighty emperor of the Maurya; in reply Ashoka sent not only gifts but also the news that he had converted to Buddhism, and a plea to Tissa to adopt the faith as well. The king does not appear to have done this at the time, instead adopting the name Devānaṃpiya "Beloved of the Gods" and having himself consecrated King of Lanka in a lavish celebration.

Emperor Ashoka took a keen interest in the propagation of Buddhism across the known world, and it was decided that his son, Mahinda, would travel to Sri Lanka and attempt to convert the people there. The events surrounding Mahinda's arrival and meeting with the king form one of the most important legends of Sri Lankan history.

According to the Mahavamsa king Devanampiyatissa was out enjoying a hunt with some 40,000 of his soldiers near a mountain called Mihintale. The date for this is traditionally associated with the full moon day of the month of Poson.

Having come to the foot of Missaka, Devanampiyatissa chased a stag into the thicket, and came across Mahinda (referred to with the honorific title Thera); the Mahavamsa has the great king 'terrified' and convinced that the Thera was in fact a 'yakka', or demon. However, Thera Mahinda declared that 'Recluses we are, O great King, disciples of the King of Dhamma (Buddha) Out of compassion for you alone have we come here from Jambudipa'. Devanampiyatissa recalled the news from his friend Ashoka and realised that these are missionaries sent from India. Thera Mahinda went on to preach to the king's company and preside over the king's conversion to Buddhism.

-- Devanampiya Tissa of Anuradhapura, by Wikipedia

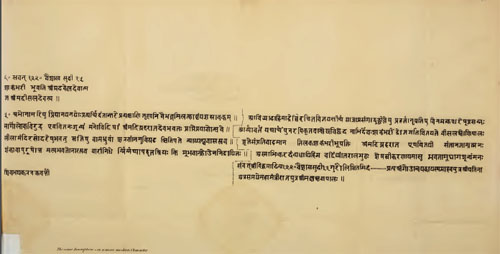

However, in 1837, George Turnour discovered Sri Lankan manuscripts (Dipavamsa, or "Island Chronicle") associating Piyadasi with Ashoka:

I proceed now to give my authority for pronouncing Piyadasi to be Dhanmasoko.

From a very early period, extending back certainly to 800 years, frequent religious missions have been mutually sent to each other's courts, by the monarchs of Ceylon and Siam, on which occasions an exchange of the Pali literature extant in either country appears to have taken place. In the several Solean and Pandian conquests of this island, the literary annals of Ceylon were extensively and intentionally destroyed. The savage Rajasingha in particular, who reigned between A.D. 1581 and 1592, and became a convert from the Buddhistical to the Brahmanical faith, industriously sought out every Buddhistical work he could find, and "delighted in burning them in heaps as high as a cocoanut tree." These losses were in great measure repaired by the embassy to Siam of Wilbagadere Mudiyanse, in the reign of Kirtisri Rajasingha in A.D. 1753, when he brought back Burmese versions of most of the Pali sacred books, a list of which is now lodged in the Dalada temple in Kandy.

The last mission of this character, undertaken however without any royal or official authority, was conducted by the chief priest of the Challia or cinnamon caste of the maritime provinces, then called Kapagama thero. He returned in 1812 with a valuable library, comprising also some historical and philological works. Some time after his return, under the instructions of the late Archdeacon of Ceylon, the Honorable Doctor Twisleton, and of the late Rev. G. Bisset, then senior colonial chaplain, Kapagama became a Convert to Christianity, and at his baptism assumed the name of George Nadoris de Silva, and he is now a modliar or chief of the cinnamon department at Colombo. He resigned his library to his senior pupil, who is the present chief priest of the Challias, and these books are chiefly kept at the wihare at Dadala near Galle. This conversion appears to have produced no estrangement or diminution of regard between the parties. It is from George Nadoris, modliar, that I received the Burmese version of the Tika of the Mahawanso, which enabled me to rectify extensive imperfections in the copy previously obtained from the ancient temple at Mulgirigalla, near Tangalle.

Some time ago the modliar suggested to me that I was wrong in supposing the Mahawanso and the Dipawanso to be the same work, as he thought he had brought the Dipawanso himself from Burmah. I was sceptical. In my last visit, however, to Colombo, he produced the book, with an air of triumph. His triumph could not exceed my delight when I found the work commenced with these lines quoted by the author of the Mahawanso* [Vide in the quarto edition the introduction to the Mahawanso, page xxxi.] as taken from the Mahawanso (another name for Dipawanso) compiled by the priests of the Utaru wihare at Anuradhapura, the ancient capital of Ceylon. "I will perspicuously set forth the visits of Buddho to Ceylon; the histories of the convocations and of the schisms of the theros; the introduction of the religion (of Buddho) into the island; and the settlement and pedigree of the sovereign Wijayo."...

In one of the narratives of this book, containing the history of Dhanmasoko, of Asandhimitta his first consort after his accession to the Indian empire, of his nephew Nigrodho, by whom he was converted to Buddhism, and of his contemporary and ally Dewananpiyatisso, the sovereign of Ceylon, — Dhanmasoko is more than once called Piyadaso, viz.:"Madhudayako pana wanijo Dewalokato chawitwa, Pupphapure rajakule uppajitwa Piyadaso kumaro hutwa chhattan ussapetwa sakala-jambadipa eka-rajjan akasi*." [Vide page 24 of the Mahawanso for an explanation of this passage.]

"The honey-dealer who was the donor thereof (to the Pache Buddho) descending by his demise from the Dewaloko heavens; being born in the royal dynasty at Pupphapura (or Patilipura, Patna); becoming the prince Piyadaso and raising the chhatta, [Parasol of dominion.] established his undivided sovereignty over the whole of Jambudipo'' — and again —

"Anagate Piyadaso, nama kumaro chhattan ussapetwa Asoka nama Dhanma Raja bhawissati."

"Hereafter the prince Piyadaso having raised the chhatta, will assume the title of Asoka the Dhanma Raja, or righteous monarch."

It would be unreasonable to multiply quotations which I could readily do, for pronouncing that Piyadaso, Piyadasino [Piyadassino is the genitive case of Piyadasi, [x]: — Ed.] or Piyadasi, according as metrical exigencies required the appellation to be written, was the name of Dhanmasoko before he usurped the Indian empire; and it is of this monarch that the amplest details are found in Pali annals. The 5th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th chapters of the Mahawanso contain exclusively the history of this celebrated ruler, and there are occasional notices of him in the Tika of that work, which also I have touched upon in my introduction to that publication. He occupies also a conspicuous place in my article No. 2, on Buddhistical annals. His history may be thus summed up.

-- Further notes on the inscriptions on the columns at Delhi, Allahabad, Betiah, &c., by the Hon'ble George Turnour, Esq. of the Ceylon Civil Service, The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. VI, Part II, Jul-Dec, 1837

"Two hundred and eighteen years after the beatitude of the Buddha, was the inauguration of Piyadassi, .... who, the grandson of Chandragupta, and the son of Bindusara, and was at the time Governor of Ujjayani."

— Dipavamsa.[4]

Since then, the association of "Devanampriya Priyadarsin" with Ashoka was reinforced through various inscriptions, and especially confirmed in the Minor Rock Edict inscription discovered in Maski, associating Ashoka with Devanampriya:[1][5]

[A proclamation] of Devanampriya Asoka.

Two and a half years [and somewhat more] (have passed) since I am a Buddha-Sakya.

[A year and] somewhat more (has passed) [since] I have visited the Samgha and have shown zeal.

Those gods who formerly had been unmingled (with men) in Jambudvipa, have how become mingled (with them).

This object can be reached even by a lowly (person) who is devoted to morality.

One must not think thus, — (viz.) that only an exalted (person) may reach this.

Both the lowly and the exalted must be told : "If you act thus, this matter (will be) prosperous and of long duration, and will thus progress to one and a half.

— Maski inscription of Ashoka.[6]

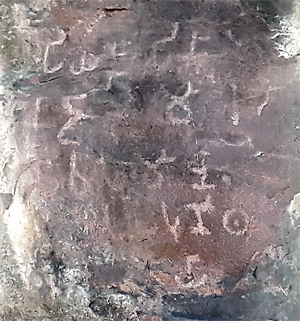

[Librarian's Comment: Contrast increased to show how the word "Ashoka" was added to the end of the first line in a rough-uneven area that the original writer was careful to avoid with respect to the entirety of the remaining inscription, that has all been rendered on the flattest-available portions of the rock face. If stones could speak, this one would cry "foul!"]

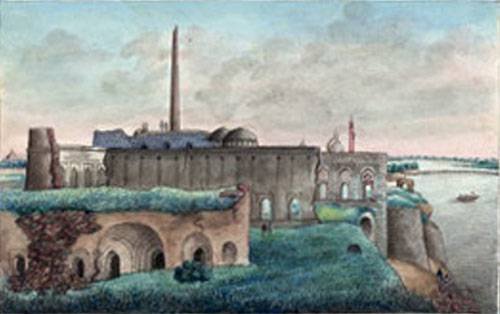

Maski is a town and an archaeological site in the Raichur district of the state of Karnataka, India. It lies on the bank of the Maski river which is a tributary of the Tungabhadra. Maski derives its name from Mahasangha or Masangi. The site came into prominence with the discovery of a minor rock edict of Emperor Ashoka by C. Beadon in 1915. It was the first edict of Emperor Ashoka that contained the name Ashoka in it instead of the earlier edicts that referred him as Devanampiye piyadasi. This edict was important to conclude that many edicts found earlier in the Indian sub-continent in the name of Devanampiye piyadasi, all belonged to Emperor Ashoka....

The Maski version of Minor Rock Edict No.1 was historically especially important in that it confirmed the association of the title "Devanampriya" ("Beloved-of-the-Gods") with Ashoka:

[A proclamation] of Devanampriya Asoka.

Two and a half years [and somewhat more] (have passed) since I am a Buddha-Sakya.

[A year and] somewhat more (has passed) [since] I have visited the Samgha and have shown zeal.

Those gods who formerly had been unmingled (with men) in Jambudvipa, have how become mingled (with them).

This object can be reached even by a lowly (person) who is devoted to morality.

One must not think thus, — (viz.) that only an exalted (person) may reach this.

Both the lowly and the exalted must be told: "If you act thus, this matter (will be) prosperous and of long duration, and will thus progress to one and a half.

— Maski Minor Rock Edict of Ashoka.

-- Maski, by Wikipedia

Historical Usage

Devānaṃpiya may refer to:

• Devanampiya Tissa of Anuradhapura (died 267 BCE), ruler of Sri Lanka based at the ancient capital of Anuradhapura from 307 to 267 BC

• Ashoka (ca. 304–232 BCE), Indian emperor of the Maurya Dynasty

• Dasharatha Maurya (ca. 232 to 224 BCE), grandson of Ashoka, in his Barabar caves inscriptions, in the form "Devanampiya Dasaratha".

• Vana-varampan, early Tamil for "the One who is Loved by the Gods" - title of a Tamil Chera chieftain of early historic south India.

References

1. The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 42.

2. Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. pp. 235–236. ISBN 9781400866328.

3. Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 37 Note 3.

4. Allen, Charles (2012). Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 79. ISBN 9781408703885.

5. Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009). Ashoka. Penguin UK. p. 13. ISBN 9788184758078.

6. Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. pp. 174–175.

**************************

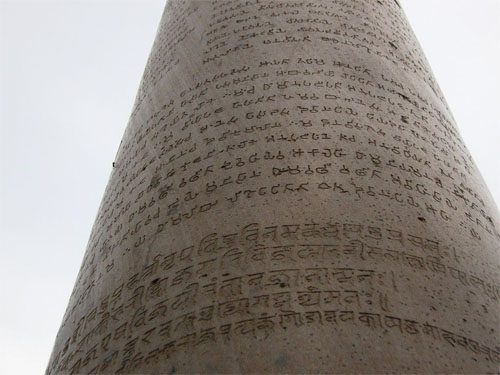

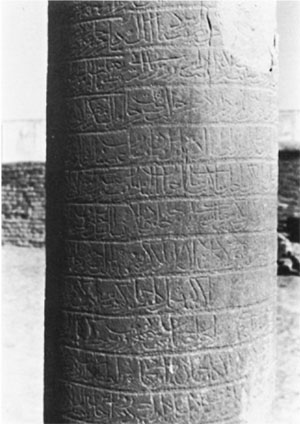

Until about a hundred years ago in India, Ashoka was merely one of the many kings mentioned in the Mauryan dynastic list included in the Puranas. Elsewhere in the Buddhist tradition he was referred to as a chakravartin/ cakkavatti, a universal monarch, but this tradition had become extinct in India after the decline of Buddhism. However, in 1837, James Prinsep deciphered an inscription written in the earliest Indian script since the Harappan, brahmi. There were many inscriptions in which the King referred to himself as Devanampiya Piyadassi (the beloved of the gods, Piyadassi). The name did not tally with any mentioned in the dynastic lists, although it was mentioned in the Buddhist chronicles of Sri Lanka. Slowly the clues were put together but the final confirmation came in 1915, with the discovery of yet another version of the edicts in which the King calls himself Devanampiya Ashoka.

-- The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to A.D. 1300, by Romila Thapar

**************************

In a study of the Mauryan period a sudden flood of source material becomes available. Whereas with earlier periods of Indian history there is a frantic search to glean evidence from sources often far removed and scattered, with the Mauryan period there is a comparative abundance of information, from sources either contemporary or written at a later date.

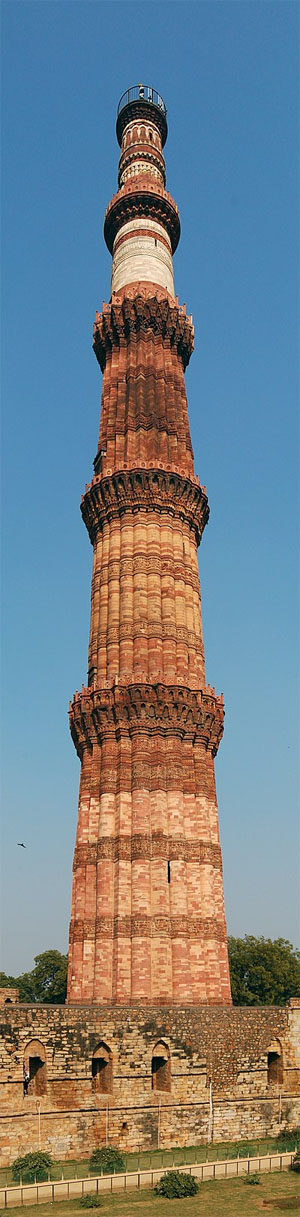

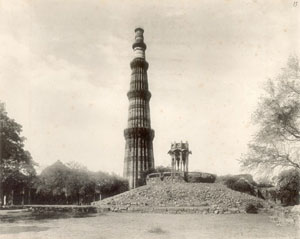

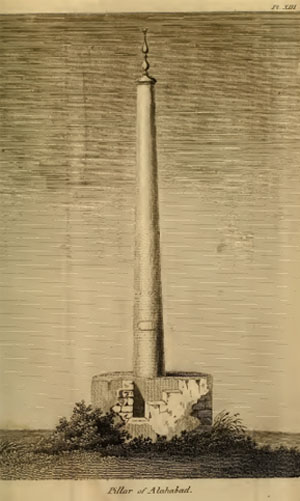

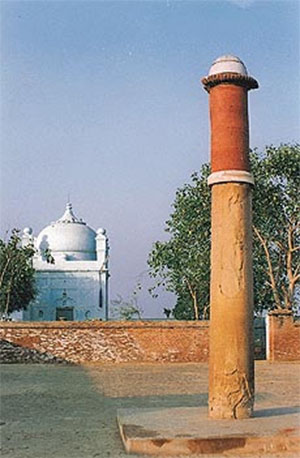

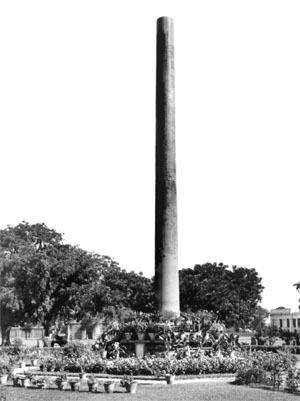

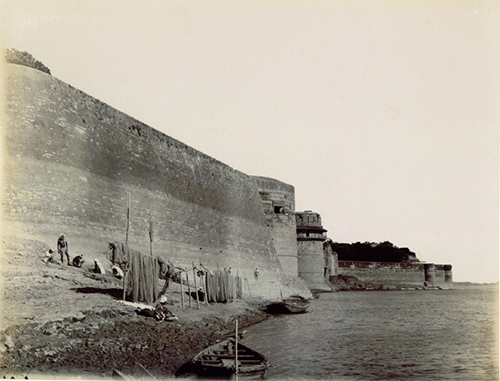

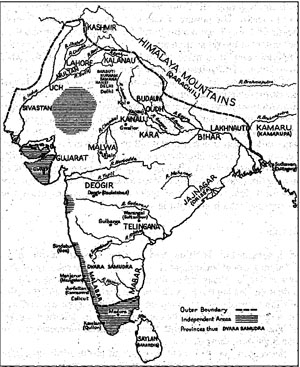

This is particularly the case with the reign of Aśoka Maurya, since, apart from the unintentional evidence of sources such as religious literature, coins, etc., the edicts of the king himself, inscribed on rocks and pillars throughout the country, are available. These consist of fourteen major rock edicts located at Kālsi, Mānsehrā, Shahbāzgarhi, Girnār, Sopārā, Yeṟṟaguḍi, Dhauli, and Jaugaḍa; and a number of minor rock edicts and inscriptions at Bairāṭ, Rūpanāth, Sahasrām, Brahmagiri, Gāvimath, Jaṭiṅga-Rāmeshwar, Maski, Pālkīguṇḍu, Rajūla-Maṇḍagiri, Siddāpura, Yeṟṟaguḍi, Gujarra and Jhansi. Seven pillar edicts exist at Allahabad, Delhi-Toprā, Delhi-Meerut, Lauriyā-Ararāja, Lauriyā-Nandangarh, and Rāmpūrvā. Other inscriptions have been found at the Barābar Caves (three inscriptions), Rummindei, Nigali-Sāgar, Allahabad, Sanchi, Sārnāth, and Bairāṭ. Recently a minor inscription in Greek and Aramaic was found at Kandahar.

The importance of these inscriptions could not be appreciated until it was ascertained to whom the title ‘Piyadassi’ referred, since the edicts generally do not mention the name of any king; an exception to this being the Maski edict, which was not discovered until very much later in 1915. The earliest publication on this subject was by Prinsep, who was responsible for deciphering the edicts. At first Prinsep identified Devanampiya Piyadassi with a king of Ceylon, owing to the references to Buddhism. There were of course certain weaknesses in this identification, as for instance the question of how a king of Ceylon could order the digging of wells and the construction of roads in India, which the author of the edicts claims to have done. Later in the same year, 1837, the Dīpavaṃsa and the Mahāvaṃsa, two of the early chronicles of the history of Ceylon, composed by Buddhist monks, were studied in Ceylon, and Prinsep was informed of the title of Piyadassi given to Aśoka in those works. This provided the link for the new and correct identification of Aśoka as the author of the edicts.

-- Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, by Romila Thapar

**************************

Legends about past lives

Buddhist legends mention stories about Ashoka's past lives. According to a Mahavamsa story, Ashoka, Nigrodha and Devnampiya Tissa were brothers in a previous life. In that life, a pratyekabuddha was looking for honey to cure another, sick pratyekabuddha. A woman directed him to a honey shop owned by the three brothers. Ashoka generously donated honey to the pratyekabuddha, and wished to become the sovereign ruler of Jambudvipa for this act of merit. The woman wished to become his queen, and was reborn as Ashoka's wife Asandhamitta....

According to an Ashokavadana story, Ashoka was born as Jaya in a prominent family of Rajagriha. When he was a little boy, he gave the Gautama Buddha dirt imagining it to be food. The Buddha approved of the donation, and Jaya declared that he would become a king by this act of merit. The text also state that Jaya's companion Vijaya was reborn as Ashoka's prime-minister Radhagupta. In the later life, the Buddhist monk Upagupta tells Ashoka that his rough skin was caused by the impure gift of dirt in the previous life. Some later texts repeat this story, without mentioning the negative implications of gifting dirt; these texts include Kumaralata's Kalpana-manditika, Aryashura's Jataka-mala, and the Maha-karma-vibhaga. The Chinese writer Pao Ch'eng's Shih chia ju lai ying hua lu asserts that an insignificant act like gifting dirt could not have been meritorious enough to cause Ashoka's future greatness. Instead, the text claims that in another past life, Ashoka commissioned a large number of Buddha statues as a king, and this act of merit caused him to become a great emperor in the next life....

Rediscovery

Ashoka had almost been forgotten, but in the 19th century James Prinsep contributed in the revelation of historical sources. After deciphering the Brahmi script, Prinsep had originally identified the "Priyadasi" of the inscriptions he found with the King of Ceylon Devanampiya Tissa. However, in 1837, George Turnour discovered an important Sri Lankan manuscript (Dipavamsa, or "Island Chronicle") associating Piyadasi with Ashoka:

"Two hundred and eighteen years after the beatitude of the Buddha, was the inauguration of Piyadassi, .... who, the grandson of Chandragupta, and the son of Bindusara, was at the time Governor of Ujjayani." — Dipavamsa

-- Ashoka, by Wikipedia

**************************

[I would like at this point to pay belated acknowledgement to my respected friend and colleague, Karl Khandalawala, which whom I have sometimes expressed differences of interpretation, in this case in opposing his view (which on hindsight appears to be entirely correct) that the Sarnath pillar reveals the influences of foreign (Achaemenid) influence.... A further issue reflecting his correctness is embodied in the self-styled title Asoka used as the opening words of many of his inscriptions (Devanampiya Piyadassi), often translated as 'Beloved of the Gods." A century ago, this term was rightly recognised by the brilliant French Indologist Emile Senart, as borrowed from earlier Achaemenid inscriptions in Persia, yet since then ignored by all authorities writing on Asoka in English.]

-- The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars, by John Irwin

**************************

[The Mahavamsa] is very important in dating the consecration of the Maurya Emperor Ashoka…

The Mahavamsa first came to the attention of Western readers around 1809 CE, when Sir Alexander Johnston, Chief Justice of the British colony in Ceylon, sent manuscripts of it and other Sri Lankan chronicles to Europe for publication. Eugène Burnouf produced a Romanized transliteration and translation into Latin in 1826... Working from Johnston's manuscripts, Edward Upham published an English translation in 1833, but it was marked by a number of errors in translation and interpretation, among them suggesting that the Buddha was born in Sri Lanka and built a monastery atop Adam's Peak. The first printed edition and widely read English translation was published in 1837 by George Turnour, an historian and officer of the Ceylon Civil Service…

Early Western scholars like Otto Franke dismissed the possibility that the Mahavamsa contained reliable historical content…

The Chinese pilgrims Fa Hsien and Hsuan Tsang both recorded myths of the origins of the Sinhala people in their travels that varied significantly from the versions recorded in the Mahavamsa…

[T]he genealogy of the Buddha recorded in the Mahavamsa describes him as being the product of four cross cousin marriages. Cross-cousin marriage is associated historically with the Dravidian people of southern India -- both Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhala practiced cross-cousin marriage historically -- but exogamous marriage was the norm in the regions of northern India associated with the life of the Buddha. No mention of cross-cousin marriage is found in earlier Buddhist sources…

The Mahavamsa is believed to have originated from an earlier chronicle known as the Dipavamsa... The Dipavamsa is much simpler and contains less information than the Mahavamsa.

-- Mahavamsa, by Wikipedia

**************************

In the meantime, Sinha-bahu and Sinhasivali, as king and queen of the kingdom of Lala (Lata), "gave birth to twin sons, sixteen times." The eldest was Vijaya and the second was Sumitta. As Vijaya was of cruel and unseemly conduct, the enraged people requested the king to kill his son. But the king caused him and his seven hundred followers to leave the kingdom, and they landed in Sri Lanka, at a place called Tamba-panni, on the exact day when the Buddha passed into Maha Parinibbana.

The Dipavamsa was translated into English by Hermann Oldenberg in 1879.

-- Dipavamsa, by Wikipedia

**************************

Governor of Ujjain

According to the Mahavamsa, Bindusara appointed Ashoka as the viceroy of present-day Ujjain (Ujjeni), which was an important administrative and commercial centre in the Avanti province of central India. This tradition is corroborated by the Saru Maru inscription discovered in central India; this inscription states that he visited the place as a prince.

The Saru Maru commemorative inscription seems to mention the presence of Ashoka [Piyadassi!] in the area of Ujjain as he was still a Prince.

In the main cave were found two inscriptions of Ashoka: a version of the Minor Rock Edict n°1, one of the Edicts of Ashoka, and another inscription mentioning the visit of Piyadasi: ...

"The king, who (now after consecration) is called "Piyadasi", (once) came to this place for a pleasure tour while still a (ruling) prince, living together with his unwedded consort."

-- Saru Maru, by Wikipedia

-- Ashoka, by Wikipedia

**************************

R. Thapar writes that the classical writers did not refer to Asoka [xxxvi]. This is clearly absurd; they must have used a different name, not Asoka or Piyadassi. A careful study shows that Devanampiya, the most common name of Asoka in the Edicts is in fact the same as Devadatta[xxxvii] or Diodotus. The interpretation of Devanampiya as `beloved of the Gods' is superficial. Asoka states that his ancestors were Devanampiyas, which shows that it is a patronymic, not a title -- even Chandragupta was a Devanampiya or Diodotus (of Erythrae). 'Nam' in Persian and 'Nomos' in Greek means 'law' another Persian word for which is 'Dat'. Thus Devanam is the same as Devadat. Piya or Priya may have had the sense of a redeemer as in the case of the name of Priam of Troy. Many Parthian Kings assumed the titles Priapatius and Assak. As can be seen from the Shahnama, the Avesta and Xerexes' inscriptions, `Deva' initially meant a clan, not god. Ignorance of this has led to senseless translations of Asoka's Edicts as `Gods mingled with men'. Only oblique scholarship has obscured that the name Devadatta occurring in the second line of Asoka's famous Taxila pillar inscription refers to Asoka himself. The line "l dmy dty `l " [xxxviii] which Marshall and Andreas translated as `for Romedatta', refers to Devadatta.

-- An Altar of Alexander Now Standing at Delhi [REDUCED VERSION], by Ranajit Pal

**************************

Asoka, the Sungas and the Andhras

After a reign of some twenty-five years, Bindusara was succeeded about 274 B.C. by his son, Asokavardhana, usually known as Asoka, whose importance in the eyes of Buddhists has given him a place in Indian history to which, from a political point of view, his grandfather is much more entitled. He is called Asokavardhana in the Puranas, and in Buddhist literature Asoka; in the only one of his inscriptions in which he refers to himself by name he is Asoka. In all his other inscriptions he is called Devanampriya, usually with the epithet Priyadarsin. The term Devanampriya, "dear to the gods" may be translated as "His Majesty"; from one of the rock edicts we learn that it was also used by his predecessors, and we find it in an inscription of his grandson, Dasaratha; in the Mudrarakshasa it is applied to his grandfather, Chandragupta. One other reference to Asoka is found, that in the Girnar inscription of the satrap Rudradaman, which calls him Asoka Maurya. It hardly required the recently discovered Maski inscription to confirm the identity of the Asoka of Buddhist tradition with the Priyadarsin or Piyadasi of the inscription. It is to these inscriptions, engraved on rock in various parts of his vast empire, that we owe the fact chat we have a picture of Asoka such as we possess of no other character in early Indian history. But although they throw some valuable light on the history of his reign, these inscriptions were not intended as historical documents.

For the events attending Asoka's accession our only source of information is Buddhist tradition.

-- The Cambridge Shorter History of India, p. 42.

**************************

The more he read, the more questions bedevilled Prinsep. Who was this King Piyadasi? At times he referred to himself as 'raja magadhe', so he must have ruled the kingdom of Magadha. None of the ancient Sanskrit lists of kings carried such a name. Then he got a lucky break. A scholar named George Turnour, working in Sri Lanka, was translating an ancient text called Mahavamsa and he discovered that there was a Lankan king named Piyadasi. But it was hard to believe that this king, ruling a tiny island south of the Indian subcontinent, could get inscriptions placed as far north as Bihar! The final link was again found in a Lankan text that explained that Piyadasi was a popular royal title and that the Lankan king shared it with another king who ruled at the same time in India. The two kings were allies and the text gave the real name of this Indian king. [NO CITATION!] A few decades later another inscription was discovered at Maski in Karnataka that confirmed it.

Raja Devanam Piyadasi's name was Ashoka.

-- Chapter 1. Discovering Ashoka, Excerpt from "Ashoka: The Great and Compassionate King", by Subhadra Sen Gupta

**************************

According to some scholars such as Christopher I. Beckwith, Ashoka, whose name only appears in the Minor Rock Edicts, should be differentiated from the ruler Piyadasi, or Devanampiya Piyadasi (i.e. "Beloved of the Gods Piyadasi", "Beloved of the Gods" being a fairly widespread title for "King"), who is named as the author of the Major Pillar Edicts and the Major Rock Edicts. Beckwith also highlights the fact that Buddhism nor the Buddha are mentioned in the Major Edicts, but only in the Minor Edicts. Further, the Buddhist notions described in the Minor Edicts (such as the Buddhist canonical writings in Minor Edict No.3 at Bairat, the mention of a Buddha of the past Kanakamuni Buddha in the Nigali Sagar Minor Pillar Edict) are more characteristic of the "Normative Buddhism" of the Saka-Kushan period around the 2nd century CE.

This inscriptional evidence may suggest that Piyadasi and Ashoka were two different rulers. According to Beckwith, Piyadasi was living in the 3rd century BCE, probably the son of Chandragupta Maurya known to the Greeks as Amitrochates, and only advocating for piety ("Dharma") in his Major Pillar Edicts and Major Rock Edicts, without ever mentioning Buddhism, the Buddha or the Samgha. Since he does mention a pilgrimage to Sambhodi (Bodh Gaya, in Major Rock Edict No.8) however, he may have adhered to an "early, pietistic, popular" form of Buddhism. Also, the geographical spread of his inscription shows that Piyadasi ruled a vast Empire, contiguous with the Seleucid Empire in the West.

On the contrary, for Beckwith, Ashoka himself was a later king of the 1st-2nd century CE, whose name only appears explicitly in the Minor Rock Edicts and allusively in the Minor Pillar Edicts, and who does mention the Buddha and the Samgha, explicitly promoting Buddhism. He may have been an unknown or possibly invented ruler named Devanampriya Asoka, with the intent of propagating a later, more institutional version of the Buddhist faith. His inscriptions cover a very different and much smaller geographical area, clustering in Central India. According to Beckwith, the inscriptions of this later Ashoka were typical of the later forms of "normative Buddhism", which are well attested from inscriptions and Gandhari manuscripts dated to the turn of the millennium, and around the time of the Kushan Empire. The quality of the inscriptions of this Ashoka is significantly lower than the quality of the inscriptions of the earlier Piyadasi.

-- Edicts of Ashoka, by Wikipedia