Part 4 of 4

See also• Early Indian epigraphy

• Lipi

• Pre-Islamic scripts in Afghanistan

• Sankhalipi

• Tamil-Brahmi

• Annaicoddai seal

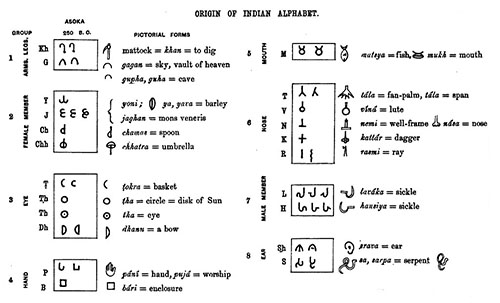

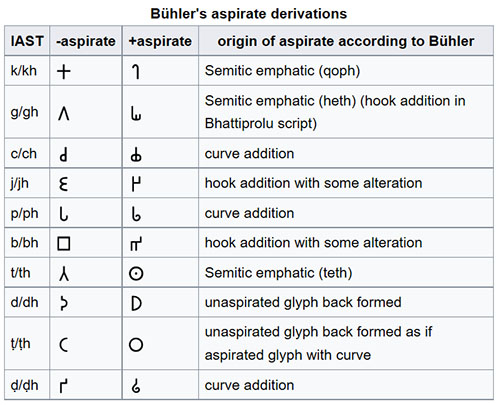

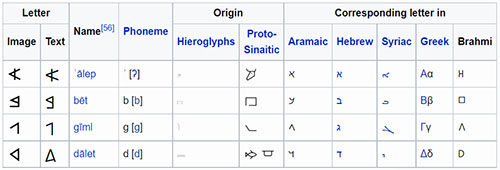

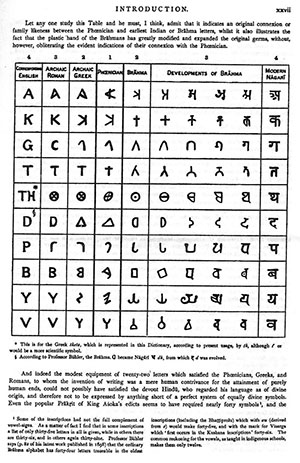

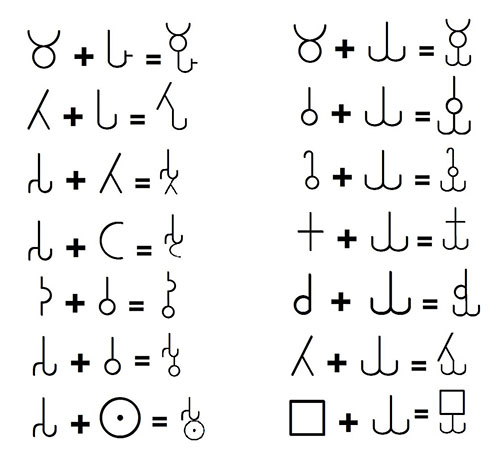

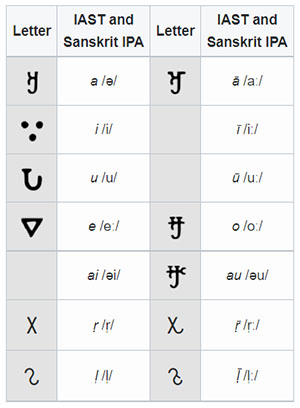

Notes1. Aramaic is written from right to left, as are several early examples of Brahmi.[58][page needed] For example, Brahmi and Aramaic g ([x] and [x] ) and Brahmi and Aramaic t ([x] and [x] ) are nearly identical, as are several other pairs.

Bühler also perceived a pattern of derivation in which certain characters were turned upside down, as with pe [x ] and [x] pa, which he attributed to a stylistic preference against top-heavy characters.

2. Bühler notes that other authors derive [x] (cha) from qoph. "M.L." indicates that the letter was used as a mater lectionis in some phase of Phoenician or Aramaic. The matres lectionis functioned as occasional vowel markers to indicate medial and final vowels in the otherwise consonant-only script. Aleph [x] and particularly ʿayin [x] only developed this function in later phases of Phoenician and related scripts, though [x] also sometimes functioned to mark an initial prosthetic (or prothetic) vowel from a very early period.[60]

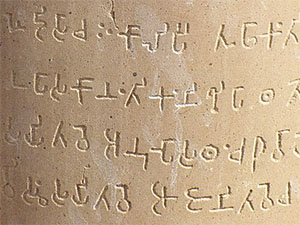

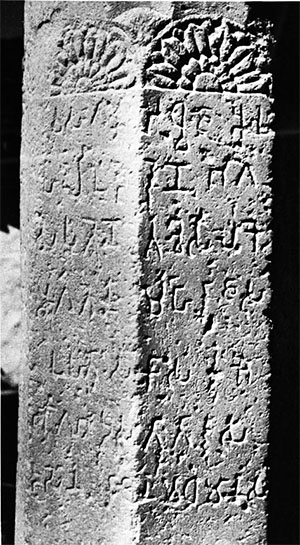

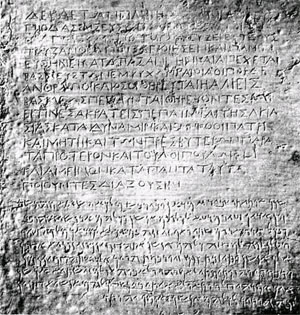

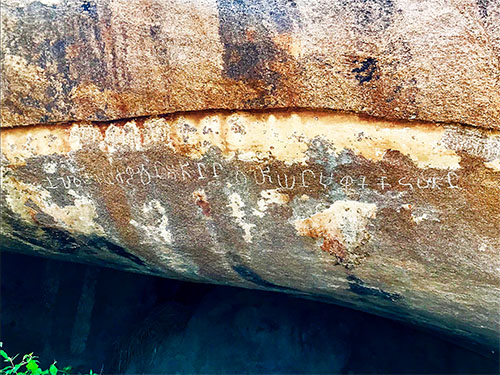

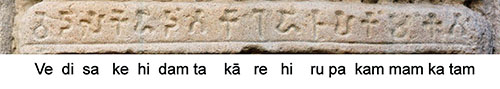

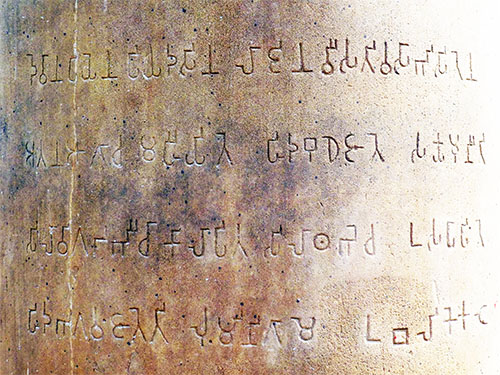

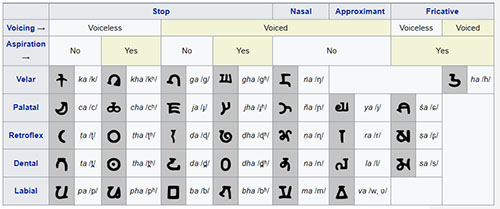

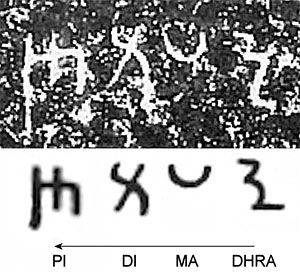

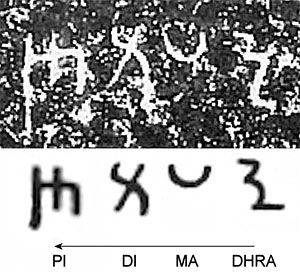

"Dhrama-Dipi" in Kharosthi script.

"Dhrama-Dipi" in Kharosthi script.3. For example, according to Hultzsch, the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (or at Mansehra) reads: "(Ayam) Dhrama-dipi Devanapriyasa Raño likhapitu" ("This Dharma-Edicts was written by King Devanampriya" Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 51.

This appears in the reading of Hultzsch's original rubbing of the Kharoshthi inscription of the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (here attached, which reads "Di" [x] rather than "Li" [x] ).

4. For example Column IV, Line 89

5.

More numerous inscribed Sanskrit records in Brahmi have been found near Mathura and elsewhere, but these are from the 1st century CE onwards.[124]

6. The archeological sites near the northern Indian city of Mathura has been one of the largest source of such ancient inscriptions. Andhau (Gujarat) and Nasik (Maharashtra) are other important sources of Brahmi inscriptions from the 1st century CE.[125]

The Indo-Greeks may have ruled as far as the area of Mathura until sometime in the 1st century BCE: the Maghera inscription, from a village near Mathura, records the dedication of a well "in the one hundred and sixteenth year of the reign of the Yavanas", which could be as late as 70 BCE....

"Menander became the ruler of a kingdom extending along the coast of western India, including the whole of Saurashtra and the harbour Barukaccha. His territory also included Mathura, the Punjab, Gandhara and the Kabul Valley", Bussagli p101)-- History of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, by Wikipedia

The Hathigumpha inscription of the Kalinga king Kharavela mentions that fearing him, a Yavana (Greek) king or general retreated to Mathura with his demoralized army. The name of the Yavana king is not clear, but it contains three letters, and the middle letter can be read as ma or mi. Some historians, such as R. D. Banerji and K.P. Jayaswal reconstructed the name of the Yavana king as "Dimita", and identified him with Demetrius.-- Demetrius I of Bactria, by Wikipedia

The amount of power delegated to Apollodotus may show that Demetrius did not expect to be able to return from Bactria to India for some time, and it is unfortunate that there is no hint to be got of what it was which kept him in Bactria. At the same time, the appointment of Demetrius II to take his brother's place as joint-king in Bactria itself is proof that Demetrius did intend to return to India sooner or later; it was obvious that he would have to, if his plan was to be carried out to its conclusion. Whether he really did return can hardly be said with any confidence; the question depends on the much defaced Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela (App. 5), which throws an uncertain light. But if it says what some scholars claim that it says, then

he did return and was somewhere in Menander's sphere in the south-east, perhaps at Mathura, when the news came of Eucratides' attack in 168; and certainly it would fit in very well with Eucratides' story if we suppose that Eucratides rather had things his own way at the start and that Demetrius did not come on the scene in Bactria till late in 168 or even 167, especially as it is just possible (p. 100) that he brought Indian troops. If so, what took Demetrius to the south-east was either that Menander was being attacked and needed reinforcements, or else he came to arrange the final campaign in which Apollodotus and Menander were to join hands; in either case he can have had no suspicion of the plans of Antiochus IV....

Alexander had found a country divided between local kings and 'free peoples' (Aratta) under their own oligarchic rule. With the kings accommodation was possible to him, for he understood kings, but it was not common: Taxiles joined him and Porus became reconciled to him, but three others -- Sambos, Musicanus, and the second Paurava king, the 'bad Porus' -- were irreconcilable, and one, Abisares, held aloof. But the free peoples -- the Asvaka of Gandhara, the Cathaei between the Ravi and the Beas, the Malavas (Malli) of the lower Ravi -- all fought him desperately; he did not understand them and they did not understand him. Subsequently this whole complex of states became part of the Mauryan empire, but that empire was nothing organic, merely a covering framework; it functioned while the central power was strong, but easily fell back into its component parts when it became weak, though the component parts might have altered meanwhile.

The Greeks met with local kings in Cutch and Surastrene, as has been seen, and at Mathura.-- Chapter IV: Demetrius and the Invasion of India, Excerpt from The Greeks in Bactria and India, by William Woodthorpe Tarn

The Datta rulers are never mentioned as "king" or Raja on their coins, suggesting that they may only have been local rulers subservient to another king. Since the Indo-Greeks were in control of Mathura around the same time frame (150–50 BCE) according to the Yavanarajya inscription, it is thought that there may have been a sort of tributary relationship between the local Datta or Mitra dynasty and the Indo-Greek kings.[History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE – 100 CE, Sonya Rhie Quintanilla, BRILL, 2007, p.8–10]

-- Datta dynasty, by Wikipedia

The Mitra dynasty refers to a group of local rulers whose name incorporated the suffix "-mitra" and who are thought to have ruled in the area of Mathura from around 150 BCE to 50 BCE, at the time of Indo-Greek hegemony over the region, and possibly in a tributary relationship with them. They are not known to have been satraps nor kings, and their coins only bear their name without any title, therefore they are sometimes simply called "the Mitra rulers of Mathura". Alternatively, they have been dated from 100 BCE to 20 BCE.

-- Mitra dynasty (Mathura), by Wikipedia

The "Great Stupa" at Sanchi is the oldest structure and was originally commissioned by the emperor Ashoka the Great of the Maurya Empire in the 3rd century BCE. Its nucleus was a hemispherical brick structure built over the relics of the Buddha, with a raised terrace encompassing its base, and a railing and stone umbrella on the summit, the chatra, a parasol-like structure symbolizing high rank.

The original Stupa only had about half the diameter of today's stupa, which is the result of enlargement by the Sungas.The Shunga Empire (IAST: Śuṅga) was an ancient Indian dynasty from Magadha that controlled areas of the central and eastern Indian subcontinent from around 184 to 75 BCE.[???]

-- Shunga Empire, by Wikipedia

It was covered in brick, in contrast to the stones that now cover it.

-- Sanchi, by Wikipedia

As for other well-known but evidently spurious "Asokan" inscriptions, note that the "Minor Pillar Inscription" at Lumbini not only mentions "Buddha" (as does, otherwise uniquely, the Calcutta-Bairat Inscription), it explicitly calls him Sakyamuni 'the Sage of the Scythians (Sakas)',64 [The Lumbini Inscription, line 3, has Budhe jate Sakyamuni ti "the Buddha Sakyamuni was born here" (Hultzsch 1925: 164).] who it says was born in Lumbini.65 [See the discussion of this and other related issues in

Phelps (2008).]

The use of the Sanskrit form of his epithet, Sakyamuni, rather than the Prakrit form, Sakamuni, is astounding and otherwise unattested until the late Gandhari documents; that fact alone rules out ascription to such an early period. But it is doubly astounding because this Sanskritism occurs in a text otherwise written completely in Mauryan Prakrit and Brahmi script. What is a Sanskrit form doing there? Sanskrit is not attested in any inscriptions or manuscripts until the Common Era or at most a few decades before it.66 [Bronkhorst (2011: 46, 50), who cites Salomon (1998:86) on the existence of four inscriptions ascribed by some, including Salomon, to the first century BC; otherwise

the earliest inscriptions in Sanskrit are from Mathura in the first and second centuries AD (Salomon 1998: 87).]

-- Appendix C: On The Early Indian Inscriptions, Excerpt from Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter With Early Buddhism in Central Asia, by Christopher I. Beckwith

The traditional idea that all were originally quarried at Chunar, just south of Varanasi and taken to their sites, before or after carving, "can no longer be confidently asserted",15 [Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, p. 22] and instead

it seems that the columns were carved in two types of stone. Some were of the spotted red and white sandstone from the region of Mathura, the others of buff-colored fine grained hard sandstone usually with small black spots quarried in the Chunar near Varanasi. The uniformity of style in the pillar capitals suggests that they were all sculpted by craftsmen from the same region. It would therefore seem that stone was transported from Mathura and Chunar to the various sites where the pillars have been found, and there was cut and carved by craftsmen.-- Pillars of Ashoka, by Wikipedia

Indo-Scythians [150 BCE–400 CE] (also called Indo-Sakas) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples of Scythian origin who migrated from Central Asia southward into northern and western regions of ancient India from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 4th century CE.The first Saka king of India was Maues/Moga (1st century BC) who established Saka power in Gandhara, and Indus Valley.

The Indo-Scythians extended their supremacy over north-western India, conquering the Indo-Greeks and other local kingdoms. The Indo-Scythians were apparently subjugated by the Kushan Empire, by either Kujula Kadphises or Kanishka....

The Indo-Scythians ultimately established a kingdom in the northwest, based near Taxila, with two great Satraps, one in Mathura in the east, and one in Surastrene (Gujarat) in the southwest....

In northern India, the Indo-Scythians conquered the area of Mathura over Indian kings around 60 BCE. Some of their satraps were Hagamasha and Hagana, who were in turn followed by the Saca Great Satrap Rajuvula.

The Mathura lion capital, an Indo-Scythian sandstone capital in crude style, from Mathura in northern India, and dated to the 1st century CE, describes in kharoshthi the gift of a stupa with a relic of the Buddha, by Queen Nadasi Kasa, the wife of the Indo-Scythian ruler of Mathura, Rajuvula. The capital also mentions the genealogy of several Indo-Scythian satraps of Mathura.

Rajuvula apparently eliminated the last of the Indo-Greek kings Strato II around 10 CE, and took his capital city, Sagala.

The coinage of the period, such as that of Rajuvula, tends to become very crude and barbarized in style. It is also very much debased, the silver content becoming lower and lower, in exchange for a higher proportion of bronze, an alloying technique (billon) suggesting less than wealthy finances.

The Mathura lion capital inscriptions attest that Mathura fell under the control of the Sakas. The inscriptions contain references to Kharahostes and Queen Ayasia, the "chief queen of the Indo-Scythian ruler of Mathura, satrap Rajuvula." Kharahostes was the son of Arta as is attested by his own coins. Arta is stated to be brother of King Moga or Maues.

The Indo-Scythian satraps of Mathura are sometimes called the "Northern Satraps", in opposition to the "Western Satraps" ruling in Gujarat and Malwa. After Rajuvula, several successors are known to have ruled as vassals to the Kushans, such as the "Great Satrap" Kharapallana and the "Satrap" Vanaspara, who are known from an inscription discovered in Sarnath, and dated to the 3rd year of Kanishka (c. AD 130), in which they were paying allegiance to the Kushans.-- Indo-Scythians, by Wikipedia

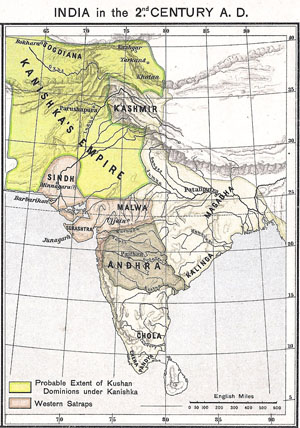

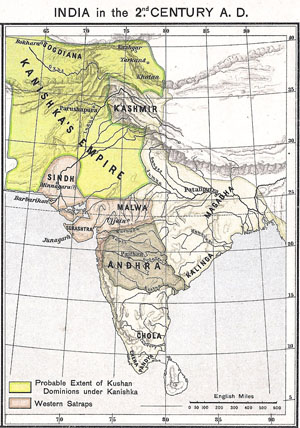

A map of India in the 2nd century AD showing the extent of the Kushan Empire (in yellow) during the reign of Kanishka. Most historians consider the empire to have variously extended as far east as the middle Ganges plain, to Varanasi on the confluence of the Ganges and the Jumna, or probably even Pataliputra....

A map of India in the 2nd century AD showing the extent of the Kushan Empire (in yellow) during the reign of Kanishka. Most historians consider the empire to have variously extended as far east as the middle Ganges plain, to Varanasi on the confluence of the Ganges and the Jumna, or probably even Pataliputra....

Several inscriptions in Sanskrit in the Brahmi script, such as the Mathura inscription of the statue of Vima Kadphises, refer to the Kushan Emperor as "Kushana"....

Rosenfield notes that archaeological evidence of a Kushan rule of long duration is present in an area stretching from Surkh Kotal, Begram, the summer capital of the Kushans, Peshawar, the capital under Kanishka I, Taxila, and Mathura, the winter capital of the Kushans....

During the Kushan Empire, many images of Gandhara share a strong resemblance to the features of Greek, Syrian, Persian and Indian figures. These Western-looking stylistic signatures often include heavy drapery and curly hair, representing a composite (the Greeks, for example, often possessed curly hair).

As the Kushans took control of the area of Mathura as well, the Art of Mathura developed considerably, and free-standing statues of the Buddha came to be mass-produced around this time, possibly encouraged by doctrinal changes in Buddhism allowing to depart from the aniconism that had prevailed in the Buddhist sculptures at Mathura, Bharhut or Sanchi from the end of the 2nd century BC. The artistic cultural influence of kushans declined slowly due to Hellenistic Greek and Indian influences.-- Kushan Empire, by Wikipedia

GAUTAMA BUDDHA, THE SCYTHIAN SAGEThe dates of Gautama Buddha are not recorded in any reliable historical source, and the traditional dates are calculated on unbelievable lineages…

His personal name, Gautama, is evidently earliest recorded in the Chuangtzu, a Chinese work from the late fourth to third centuries BC….

His epithet Sakamuni (later Sanskritized as Sakyamuni), 'Sage of the Scythians ("Sakas")', is unattested in the genuine Mauryan inscriptions or the Pali Canon.

It is earliest attested, as Sakamuni, in the Gandhari Prakrit texts, which date to the first centuries AD (or possibly even the late first century BC)….

It is thus arguable that the epithet could have been applied to the Buddha during the Saka (Saka or "Indo-Scythian") Dynasty -- which dominated northwestern India on and off from approximately the first century BC, continuing into the early centuries AD as satraps or "vassals" under the Kushans -- and that the reason for it was strong support for Buddhism by the Sakas, Indo-Parthians, and Kushans....

The Buddha must have passed away well before 325 to 304 BC, the dates for the appearance of the earliest hard evidence on the existence of Buddhism or elements of Buddhism. This is still three centuries before even the earliest Gandhari texts and the traditional (high) date of the Pali Canon. Despite widespread belief that the latter collections of material, both of which are from the Saka-Kushan period or later, represent "Early Buddhism", the work of many scholars has shown that even by internal evidence alone it must be already quite far removed from the earliest Buddhism -- the teachings and practices of the followers of the Buddha himself and the next few generations after him, up to the mid-third century BC.

-- Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter With Early Buddhism in Central Asia, by Christopher I. Beckwith

References1. Salomon 1998, pp. 11–13.

2. Salomon 1998, p. 20.

3. Salomon 1998, p. 17 Quote: " Until the late nineteenth century, the script of the Aśokan (non-Kharosthi) inscriptions and its immediate derivatives was referred to by various names such as “lath” or “Lat,” “Southern Aśokan,” “Indian Pali,” “Mauryan,” and so on. The application to it of the name Brahmi [sc. lipi], which stands at the head of the Buddhist and Jaina script lists, was first suggested by T[errien] de Lacouperie, who noted that in the Chinese Buddhist encyclopedia Fa yiian chu lin the scripts whose names corresponded to the Brahmi and Kharosthi of the Lalitavistara are described as written from left to right and from right to left, respectively. He therefore suggested that the name Brahmi should refer to the left-to-right “Indo-Pali” script of the Aśokan pillar inscriptions, and Kharosthi to the right-to-left “Bactro-Pali” script of the rock inscriptions from the northwest."

4. Salomon 1998, p. 17 Quote: "... the Brahmi script appeared in the third century B.c. as a fully developed pan-Indian national script (sometimes used as a second script even within the proper territory of Kharosthi in the north-west) and continued to play this role throughout history, becoming the parent of all of the modern Indic scripts both within India and beyond. Thus, with the exceptions of the Indus script in the protohistoric period, of Kharosthi in the northwest in the ancient period, and of the Perso–Arabic and European scripts in the medieval and modern periods, respectively, the history of writing in India is virtually synonymous with the history of the Brahmi script and its derivatives.

5. Salomon 1998, pp. 42–46 "The presumptive homeland and principal area of the use of Kharoṣțhī script ... was the territory along and around the Indus, Swat, and Kabul River Valleys of the modern North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan; ... [pp. 42–44] In short, there is no clear evidence to allow us to specify the date of the origin of Kharoṣțhī with any more precision than sometime in the fourth, or possibly the fifth, century B.C. [p. 46]"

6. Salomon 1998, pp. 19–30.

7. Salomon, Richard (1995). "On The Origin Of The Early Indian Scripts: A Review Article". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670. Archived from the original on 2019-05-22. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

8. "Brahmi". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1999. Among the many descendants of Brāhmī are Devanāgarī (used for Sanskrit, Hindi and other Indian languages), the Bengali and Gujarati scripts and those of the Dravidian languages

9. Beckwith, Christopher I. (2017). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

10. Lahiri, Nayanjot (2015), Ashoka in Ancient India, Harvard University Press, pp. 14, 15, ISBN 978-0-674-05777-7, Facsimiles of the objects and writings unearthed—from pillars in North India to rocks in Orissa and Gujarat—found their way to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The meetings and publications of the Society provided an unusually fertile environment for innovative speculation, with scholars constantly exchanging notes on, for instance, how they had deciphered the Brahmi letters of various epigraphs from Samudragupta’s Allahabad pillar inscription, to the Karle cave inscriptions. The Eureka moment came in 1837 when James Prinsep, a brilliant secretary of the Asiatic Society, building on earlier pools of epigraphic knowledge, very quickly uncovered the key to the extinct Mauryan Brahmi script. Prinsep unlocked Ashoka; his deciphering of the script made it possible to read the inscriptions.

11. Thapar, Romila (2004), Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300, University of California Press, pp. 11, 178–179, ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8, The nineteenth century saw considerable advances in what came to be called Indology, the study of India by non-Indians using methods of investigation developed by European scholars in the nineteenth century. In India the use of modern techniques to ‘rediscover’ the past came into practice. Among these was the decipherment of the brahmi script, largely by James Prinsep. Many inscriptions pertaining to the early past were written in brahmi, but knowledge of how to read the script had been lost. Since inscriptions form the annals of Indian history, this decipherment was a major advance that led to the gradual unfolding of the past from sources other than religious and literary texts. (p. 11) ... Until about a hundred years ago in India, Ashoka was merely one of the many kings mentioned in the Mauryan dynastic list included in the Puranas. Elsewhere in the Buddhist tradition he was referred to as a chakravartin, ..., a universal monarch but this tradition had become extinct in India after the decline of Buddhism. However, in 1837, James Prinsep deciphered an inscription written in the earliest Indian script since the Harappan, brahmi. There were many inscriptions in which the King referred to himself as Devanampiya Piyadassi (the beloved of the gods, Piyadassi). The name did not tally with any mentioned in the dynastic lists, although it was mentioned in the Buddhist chronicles of Sri Lanka. Slowly the clues were put together but the final confirmation came in 1915, with the discovery of yet another version of the edicts in which the King calls himself Devanampiya Ashoka. (pp. 178-179)

12. Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015), The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE–200 CE, Cambridge University Press, pp. 71–72, ISBN 978-0-521-84697-4, Like William Jones, Prinsep was also an important figure within the Asiatic Society and is best known for deciphering early Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts. He was something of a polymath, undertaking research into chemistry, meteorology, Indian scriptures, numismatics, archaeology and mineral resources, while fulfilling the role of Assay Master of the East India Company mint in East Bengal (Kolkatta). It was his interest in coins and inscriptions that made him such an important figure in the history of South Asian archaeology, utilising inscribed Indo-Greek coins to decipher Kharosthi and pursuing earlier scholarly work to decipher Brahmi. This work was key to understanding a large part of the Early Historical period in South Asia ...

13. Kopf, David (2021), British Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance: The Dynamics of Indian Modernization 1773-1835, Univ of California Press, pp. 265–266, ISBN 978-0-520-36163-8, In 1837, four years after Wilson's departure, James Prinsep, then Secretary of the Asiatic Society, unravelled the mystery of the Brahmi script and thus was able to read the edicts of the great Emperor Asoka. The rediscovery of Buddhist India was the last great achievement of the British orientalists. The later discoveries would be made by Continental Orientalists or by Indians themselves.

14. Verma, Anjali (2018), Women and Society in Early Medieval India: Re-interpreting Epigraphs, London: Routledge, pp. 27–, ISBN 978-0-429-82642-9, In 1836, James Prinsep published a long series of facsimiles of ancient inscriptions, and this series continued in volumes of the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. The credit for decipherment of the Brahmi script goes to James Prinsep and thereafter Georg Buhler prepared complete and scientific tables of Brahmi and Khrosthi scripts.

15. Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2016), A History of India, London: Routledge, pp. 39–, ISBN 978-1-317-24212-3, Ashoka’s reign of more than three decades is the first fairly well-documented period of Indian history. Ashoka left us a series of great inscriptions (major rock edicts, minor rock edicts, pillar edicts) which are among the most important records of India’s past. Ever since they were discovered and deciphered by the British scholar James Prinsep in the 1830s, several generations of Indologists and historians have studied these inscriptions with great care.

16. Wolpert, Stanley A. (2009), A New History of India, Oxford University Press, p. 62, ISBN 978-0-19-533756-3, James Prinsep, an amateur epigraphist who worked in the British mint in Calcutta, first deciphered the Brāhmi script.

17. Chakrabarti, Pratik (2020), Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity, Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 48–, ISBN 978-1-4214-3874-0, Prinsep, the Orientalist scholar, as the secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1832-39), oversaw one of the most productive periods of numismatic and epigraphic study in nineteenth-century India. Between 1833 and 1838, Prinsep published a series of papers based on Indo-Greek coins and his deciphering of Brahmi and Kharoshthi scripts.

18. Salomon 1998, pp. 204–205 "Prinsep came to India in 1819 as assistant to the assay master of the Calcutta Mint and remained until 1838, when he returned to England for reasons of health. During this period Prinsep made a long series of discoveries in the fields of epigraphy and numismatics as well as in the natural sciences and technical fields. But he is best known for his breakthroughs in the decipherment of the Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts. ... Although Prinsep's final decipherment was ultimately to rely on paleographic and contextual rather than statistical methods, it is still no less a tribute to his genius that he should have thought to apply such modern techniques to his problem."

19. Sircar, D.C. (2017) [1965]. Indian Epigraphy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-81-208-4103-1. The work of the reconstruction of the early period of Indian history was inaugurated by European scholars in the 18th century. Later on, Indians also became interested in the subject. The credit for the decipherment of early Indian inscriptions, written in the Brahmi and Kharosthi alphabets, which paved the way for epigraphical and historical studies in India, is due to scholars like Prinsep, Lassen, Norris and Cunningham.

20. Garg, Sanjay (2017). "Charles Masson: A footloose antiquarian in Afghanistan and the building up of numismatic collections in museums in India and England". In Himanshu Prabha Ray (ed.). Buddhism and Gandhara: An Archaeology of Museum Collections. Taylor & Francis. pp. 181–. ISBN 978-1-351-25274-4.

21. Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). "Kharosti and Brahmi". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 122 (2): 391–393. doi:10.2307/3087634. JSTOR 3087634.

22. Keay 2000, p. 129–131.

23. Falk 1993, p. 106.

24. Rajgor 2007.

25. Trautmann 2006, p. 64.

26. Plofker 2009, pp. 44–45.

27. Plofker 2009, p. 45.

28. Plofker 2009, p. 47"A firm upper bound for the date of this invention is attested by a Sanskrit text of the mid-third century CE, the Yavana-jātaka or “Greek horoscopy” of one Sphujidhvaja, which is a versified form of a translated Greek work on astrology. Some numbers in this text appear in concrete number format"

29. Hayashi 2003, p. 119.

30. Plofker 2007, pp. 396–397.

31. Chhabra, B. Ch. (1970). Sugh Terracotta with Brahmi Barakhadi: appears in the Bulletin National Museum No. 2. New Delhi: National Museum.

32. Georg Bühler (1898). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet. K.J. Trübner. pp. 6, 14–15, 23, 29., Quote: "(...) a passage of the Lalitavistara which describes the first visit of Prince Siddhartha, the future Buddha, to the writing school..." (page 6); "In the account of Prince Siddhartha's first visit to the writing school, extracted by Professor Terrien de la Couperie from the Chinese translation of the Lalitavistara of 308 AD, there occurs besides the mention of the sixty-four alphabets, known also from the printed Sanskrit text, the utterance of the Master Visvamitra[.]"

33. Salomon 1998, pp. 8–10 with footnotes

34. Nado, Lopon (1982). "The Development of Language in Bhutan". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 5 (2): 95. Under different teachers, such as the Brahmin Lipikara and Deva Vidyasinha, he mastered Indian philology and scripts. According to Lalitavistara, there were as many as sixty-four scripts in India.

35. Tsung-i, Jao (1964). "Chinese Sources on Brāhmī and Kharoṣṭhī". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 45 (1/4): 39–47. JSTOR 41682442.

36. Salomon 1998, p. 9.

37. Falk 1993, pp. 109–167.

38. Salomon 1998, pp. 19–20

39. Salomon 1996, p. 378.

40. Bühler 1898, p. 2.

41. Goyal, S. R. (1979). S. P. Gupta; K. S. Ramachandran (eds.). The Origin of Brahmi Script., cited after Salomon (1998).

42. Salomon 1998, p. 19, fn. 42: "there is no doubt some truth in Goyal's comment that some of their views have been affected by 'nationalist bias' and 'imperialist bias,' respectively."

43. Cunningham, Alexander (1877). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing. p. 54.

44. F. R. Allchin; George Erdosy (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2.

45. L. A. Waddell (1914), Besnagar Pillar Inscription B Re-Interpreted, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press, pages 1031-1037

46. Brahmi, Encyclopedia Britannica (1999), Quote: "Brāhmī, writing system ancestral to all Indian scripts except Kharoṣṭhī. Of Aramaic derivation or inspiration, it can be traced to the 8th or 7th century BC, when it may have been introduced to Indian merchants by people of Semitic origin. (...) a coin of the 4th century BC, discovered in Madhya Pradesh, is inscribed with Brāhmī characters running from right to left."

47. Salomon 1998, pp. 18–24.

48. Salomon 1998, pp. 23, 46–54

49. Salomon 1998, p. 19-21 with footnotes.

50. Annette Wilke & Oliver Moebus 2011, p. 194 with footnote 421.

51. Trigger, Bruce G. (2004), "Writing Systems: a case study in cultural evolution", in Stephen D. Houston (ed.), The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, Cambridge University Press, pp. 60–61

52. Justeson, J.S.; Stephens, L.D. (1993). "The evolution of syllabaries from alphabets". Die Sprache. 35: 2–46.

53. Bühler 1898, p. 84–91.

54. Salomon 1998, pp. 23–24.

55. Salomon 1998, p. 28.

56. after Fischer, Steven R. (2001). A History of Writing. London: Reaction Books. p. 126.

57. Bühler 1898, p. 59,68,71,75.

58. Salomon 1996.

59. Salomon 1998, p. 25.

60. Andersen, F.I.; Freedman, D.N. (1992). "Aleph as a vowel in Old Aramaic". Studies in Hebrew and Aramaic Orthography. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. pp. 79–90.

61. Bühler 1898, p. 76-77.

62. Bühler 1898, p. 82-83.

63. Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. (2009), The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, John Wiley and Sons Ltd., pp. 173–174

64. Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

65. Scharfe, Hartmut (2002), Education in Ancient India, Handbook of Oriental Studies, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers, pp. 10–12

66. Tavernier, Jan (2007). "The Case of Elamite Tep-/Tip- and Akkadian Tuppu". Iran. 45: 57–69. doi:10.1080/05786967.2007.11864718. S2CID 191052711. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

67. "Falk goes too far. It is fair to expect that we believe that Vedic memorisation — though without parallel in any other human society — has been able to preserve very long texts for many centuries without losing a syllable. (...) However, the oral composition of a work as complex as Pāṇini's grammar is not only without parallel in other human cultures, it is without parallel in India itself. (...) It just will not do to state that our difficulty in conceiving any such thing is our problem." Bronkhorst, Johannes (2002). "Literacy and Rationality in Ancient India". Asiatische Studien/Études Asiatiques. 56 (4): 803–804, 797–831.

68. Falk 1993.

69. Annette Wilke & Oliver Moebus 2011, p. 194, footnote 421.

70. Salomon, Richard (1995). "Review: On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–278. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

71. Salomon 1998, p. 22.

72. Salomon 1998, pp. 23.

73. Falk 1993, pp. 104.

74. Salomon 1998, pp. 19–24.

75. Falk, Harry (2018). "The Creation and Spread of Scripts in Ancient India". Literacy in Ancient Everyday Life, Pp.43-66: see pages 57–58 for the online publication. doi:10.1515/9783110594065-004. ISBN 9783110594065. S2CID 134470331.

76. Iravatham Mahadevan (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy. Harvard University Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies. pp. 91–94. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.;

Iravatham Mahadevan (1970). Tamil-Brahmi Inscriptions. State Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamil Nadu. pp. 1–12.

77. Bertold Spuler (1975). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Brill Academic. p. 44. ISBN 90-04-04190-7.

78. John Marshall (1931). Mohenjo-daro and the Indus civilization: being an official account of archaeological excavations at Mohenjo-Daro carried out by the government of India between the years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services. p. 423. ISBN 978-81-206-1179-5., Quote: "Langdon also suggested that the Brahmi script was derived from the Indus writing, (...)".

79. Senarat Paranavitana; Leelananda Prematilleka; Johanna Engelberta van Lohuizen-De Leeuw (1978). Studies in South Asian Culture: Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume. Brill Academic. p. 119. ISBN 90-04-05455-3.

80. Hunter, G.R. (1934), The Script of Harappa and Mohenjodaro and Its Connection with Other Scripts, Studies in the history of culture, London:K. Paul, Trench, Trubner

81. Goody, Jack (1987), The Interface Between the Written and the Oral, Cambridge University Press, pp. 301–302 (note 4)

82. Allchin, F.Raymond; Erdosy, George (1995), The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States, Cambridge University Press, p. 336

83. Georg Feuerstein; Subhash Kak; David Frawley (2005). The Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-81-208-2037-1.

84. Jack Goody (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. pp. 301 footnote 4. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6., Quote: "In recent years, I have been leaning towards the view that the Brahmi script had an independent Indian evolution, probably emerging from the breakdown of the old Harappan script in the first half of the second millennium BC".

85. Senarat Paranavitana; Leelananda Prematilleka; Johanna Engelberta van Lohuizen-De Leeuw (1978). Studies in South Asian Culture: Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume. Brill Academic. pp. 119–120 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-05455-3.

86. Kak, Subhash (1994), "The evolution of early writing in India" (PDF), Indian Journal of History of Science, 28: 375–388

87. Kak, S. (2005). Akhenaten, Surya, and the Rigveda. in "The Golden Chain" Govind Chandra Pande (editor), CRC, 2005.

http://www.ece.lsu.edu/kak/Akhenaten.pdf88. Kak, S. (1988). A frequency analysis of the Indus script. Cryptologia 12: 129–143.

http://www.ece.lsu.edu/kak/IndusFreqAnalysis.pdf89. Kak, S. (1990) Indus and Brahmi – further connections, Cryptologia 14: 169–183

90. Das, S. ; Ahuja, A. ; Natarajan, B. ; Panigrahi, B.K. (2009) Multi-objective optimization of Kullback-Leibler divergence between Indus and Brahmi writing. World Congress on Nature & Biologically Inspired Computing, 2009. NaBIC 2009.1282 – 1286. ISBN 978-1-4244-5053-4

91. Salomon 1998, pp. 20–21.

92. Khan, Omar. "Mahadevan Interview: Full Text". Harappa. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

93. Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2006), "Inscribed pots, emerging identities", in Patrick Olivelle (ed.), Between the Empires : Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE, Oxford University Press, pp. 121–122

94. Fábri, C. L. (1935). "The Punch-Marked Coins: A Survival of the Indus Civilization". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 67 (2): 307–318. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00086482. JSTOR 25201111.

95. Salomon 1998, p. 21.

96. Masica 1993, p. 135.

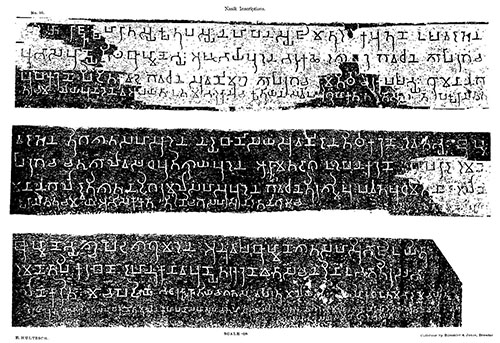

97. Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii.

98. Sharma, R. S. (2006). India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780199087860.

99. "The word dipi appears in the Old Persian inscription of Darius I at Behistan (Column IV. 39) having the meaning inscription or "written document" in Congress, Indian History (2007). Proceedings – Indian History Congress. p. 90.

100. Scharfe, Hartmut (2002), Education in Ancient India, Handbook of Oriental Studies, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers, p. 9

101. Strabo (1903). Hamilton, H.C.; Falconer, W. (eds.). The Geography of Strabo. Literally translated, with notes, in three volumes. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 15.1.53.

102. Rocher 2014.

103. Timmer 1930, p. 245.

104. Strabo (1903). Hamilton, H.C.; Falconer, W. (eds.). The Geography of Strabo. Literally translated, with notes, in three volumes. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 15.1.39.

105. Sterling, Gregory E. (1992). Historiography and Self-Definition: Josephos, Luke-Acts, and Apologetic Historiography. Brill. p. 95.

106. McCrindle, J.W. (1877). Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian. London: Trübner and Co. pp. 40, 209. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

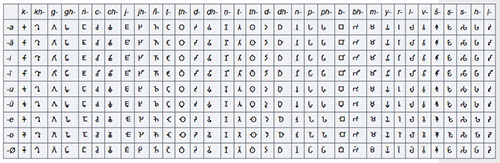

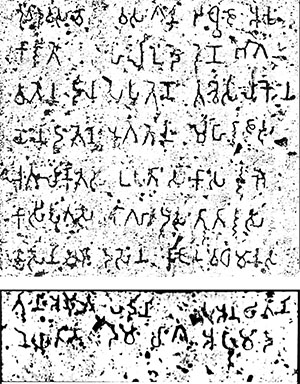

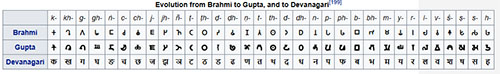

107. Salomon 1998, p. 11.

108. Oskar von Hinüber (1989). Der Beginn der Schrift und frühe Schriftlichkeit in Indien. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur. pp. 241–245. ISBN 9783515056274. OCLC 22195130.

109. Kenneth Roy Norman (2005). Buddhist Forum Volume V: Philological Approach to Buddhism. Routledge. pp. 67, 56–57, 65–73. ISBN 978-1-135-75154-8.

110. Norman, Kenneth R. “THE DEVELOPMENT OF WRITING IN INDIA AND ITS EFFECT UPON THE PĀLI CANON.” Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Südasiens / Vienna Journal of South Asian Studies, vol. 36, 1992, pp. 239–249. JSTOR,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/24010823. Accessed 11 May 2020.

111. Jack Goody (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. pp. 110–124. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6.

112. Jack Goody (2010). Myth, Ritual and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–47, 65–81. ISBN 978-1-139-49303-1.

113. Annette Wilke & Oliver Moebus 2011, pp. 182–183.

114. Walter J. Ong; John Hartley (2012). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Routledge. pp. 64–69. ISBN 978-0-415-53837-4.

115. Salomon 1998, pp. 8–9

116. Nagrajji, Acharya Shri (2003). Āgama Aura Tripiṭaka, Eka Anuśilana: Language and literature. New Delhi: Concept Publishing. pp. 223–224.

117. Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 351. ISBN 9788131711200.

118. Levi, Silvain (1906), "The Kharostra Country and the Kharostri Writing", The Indian Antiquary, XXXV: 9

119. Monier Monier-Williams (1970). Sanskrit-English dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass (Reprint of Oxford Claredon). p. xxvi with footnotes. ISBN 978-5-458-25035-1.

120. Arthur Anthony Macdonell (2004). Sanskrit English Dictionary (Practical Hand Book). Asian Educational Services. p. 200. ISBN 978-81-206-1779-7.

121. Monier Monier Willians (1899), Brahmi, Oxford University Press, page 742

122. Salomon 1998, pp. 72–81.

123. Salomon 1998, pp. 86–87.

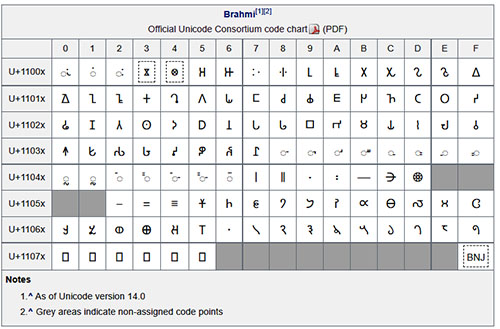

124. Salomon 1998, pp. 87–89.

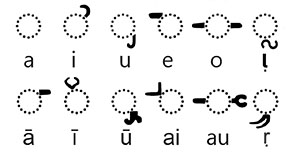

125. Salomon 1998, p. 82.

126. Salomon 1998, pp. 81–84.

127. Salomon 1996, p. 377.

128. Salomon 1998, pp. 122–123, 129–131, 262–307.

129. Salomon 1998, pp. 12–13.

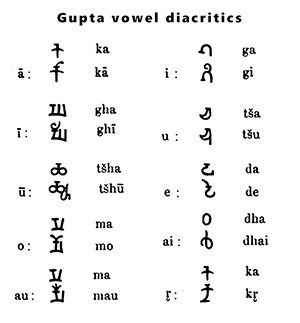

130. Coningham, R.A.E.; Allchin, F.R.; Batt, C.M.; Lucy, D. (22 December 2008). "Passage to India? Anuradhapura and the Early Use of the Brahmi Script". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 6 (1): 73. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001608.

131. Falk, H. (2014). "Owner's graffiti on pottery from Tissamaharama", in Zeitchriftfür Archäeologie Aussereuropäischer Kulturen. 6. pp.45–47.

132. Rajan prefers the term "Prakrit-Brahmi" to distinguish Prakrit-language Brahmi inscriptions.

133. Rajan, K.; Yatheeskumar, V.P. (2013). "New evidences on scientific dates for Brāhmī Script as revealed from Porunthal and Kodumanal Excavations" (PDF). Prāgdhārā. 21–22: 280–295. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

134. Falk, H. (2014), p.46, with footnote 2

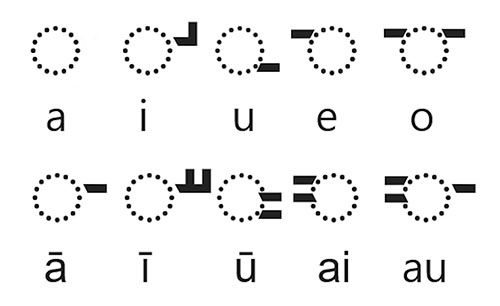

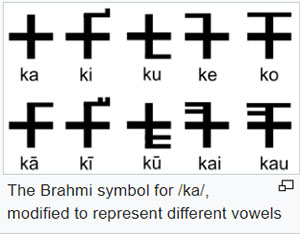

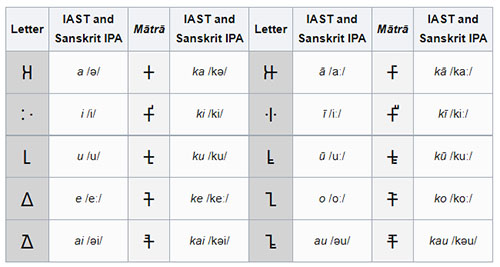

135. Salomon 1998, pp. 204–208 Equally impressive was Prinsep's arrangement, presented in plate V of JASB 3, of the unknown alphabet, wherein he gave each of the consonantal characters, whose phonetic values were still entirely unknown, with its "five principal inflections", that is, the vowel diacritics. Not only is this table almost perfectly correct in its arrangement, but the phonetic value of the vowels is correctly identified in four out of five cases (plus anusvard); only the vowel sign for i was incorrectly interpreted as o.

136. Salomon 1998, pp. 204–208

137. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol V 1836. p. 723.

138. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1838.

139. Salomon 1998, pp. 204–206.

140. Salomon 1998, pp. 206–207

141. Daniels, Peter T. (1996), "Methods of Decipherment", in Peter T. Daniels, William Bright (ed.), The World's Writing Systems, Oxford University Press, pp. 141–159, 151, ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7, Brahmi: The Brahmi script of Ashokan India (SECTION 30) is another that was deciphered largely on the basis of familiar language and familiar related script—but it was made possible largely because of the industry of young James Prinsep (1799-1840), who inventoried the characters found on the immense pillars left by Ashoka and arranged them in a pattern like that used for teaching the Ethiopian abugida (FIGURE 12). Apparently, there had never been a tradition of laying out the full set of aksharas thus—or anyone, Prinsep said, with a better knowledge of Sanskrit than he had had could have read the inscriptions straight away, instead of after discovering a very minor virtual bilingual a few years later. (p. 151)

142. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1834. pp. 495–499.

143. Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XII.

144. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol V 1836. p. 723.

145. Asiatic Society of Bengal (1837). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Oxford University.

146. More details about Buddhist monuments at Sanchi Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Archaeological Survey of India, 1989.

147. Extract of Prinsep's communication about Lassen's decipherment in Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol V 1836. 1836. pp. 723–724.

148. Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XI.

149. Keay, John (2011). To cherish and conserve the early years of the archaeological survey of India. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 30–31.

150. Four Reports Made During the Years 1862-63-64-65 by Alexander Cunningha M: 1/ by Alexander Cunningham. 1. Government central Press. 1871. p. XIII.

151. Salomon 1998, p. 207.

152. Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor, Charles Allen, Little, Brown Book Group Limited, 2012

153. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1838. pp. 219–285.

154. Salomon 1998, p. 208.

155. Epigraphia Zeylanica: 1904–1912, Volume 1. Government of Sri Lanka, 1976.

http://www.royalasiaticsociety.lk/inscr ... ?q=node/12 Archived 2016-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

156. Raghupathy, Ponnambalam (1987). Early settlements in Jaffna, an archaeological survey. Madras: Raghupathy.

157. P Shanmugam (2009). Hermann Kulke; et al. (eds.). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 208. ISBN 978-981-230-937-2.

158. Frederick Asher (2018). Matthew Adam Cobb (ed.). The Indian Ocean Trade in Antiquity: Political, Cultural and Economic Impacts. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-138-73826-3.

159. Salomon 1998, pp. 27–28.

160. Salomon 1996, pp. 373–4.

161. Bühler 1898, p. 32.

162. Bühler 1898, p. 33.

163. Daniels, Peter T. (2008), "Writing systems of major and minor languages", Language in South Asia, Cambridge University Press, p. 287

164. Trautmann 2006, p. 62–64.

165. Chakrabarti, Manika (1981). Mālwa in Post-Maurya Period: A Critical Study with Special Emphasis on Numismatic Evidences. Punthi Pustak. p. 100.

166. Ram Sharma, Brāhmī Script: Development in North-Western India and Central Asia, 2002

167. Stefan Baums (2006). "Towards a computer encoding for Brahmi". In Gail, A.J.; Mevissen, G.J.R.; Saloman, R. (eds.). Script and Image: Papers on Art and Epigraphy. New Delhi: Shri Jainendra Press. pp. 111–143.

168. Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 43. ISBN 9788131711200.

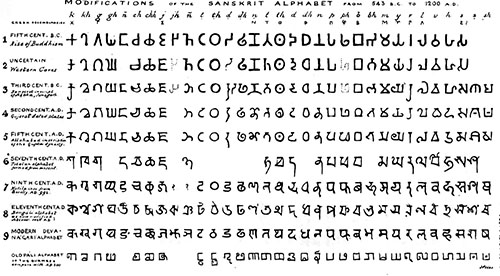

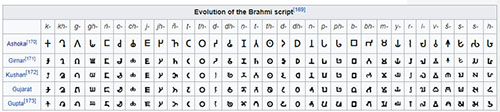

169. Evolutionary chart, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 7, 1838 [1]

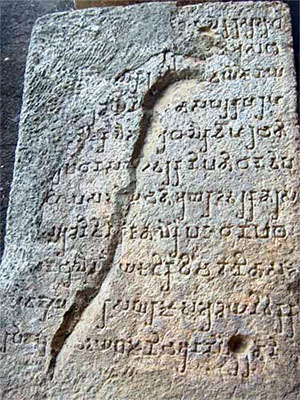

170. Inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka

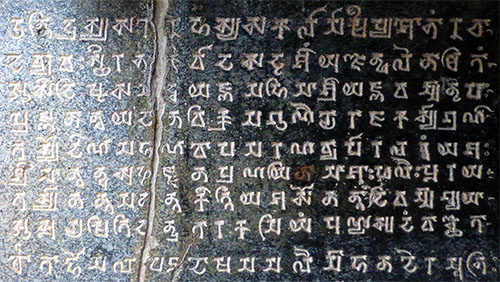

171. Inscriptions of Western Satrap Rudradaman I on the rock at Girnar circa 150 CE

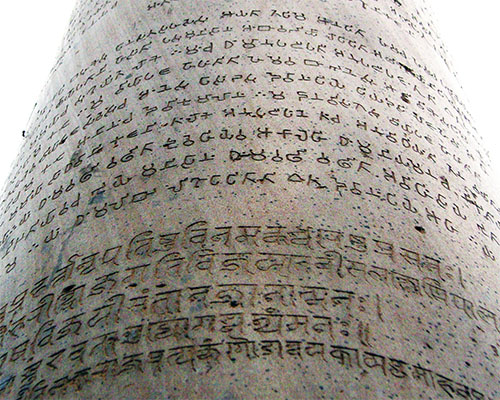

172. Kushan Empire inscriptions circa 150-250 CE.

173. Gupta Empire inscription of the Allahabad Pillar by Samudragupta circa 350 CE.

174. Google Noto Fonts – Download Noto Sans Brahmi zip file

175. Adinatha font announcement

176. Script and Font Support in Windows – Windows 10 Archived 2016-08-13 at the Wayback Machine, MSDN Go Global Developer Center.

177. Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 164–165.

178. Avari, Burjor (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from C. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 9781317236733.

179. Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries Shane Wallace, 2016, p.222-223

180. Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

181. Burjor Avari (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from C. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Routledge. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-1-317-23673-3.

182. Romila Thapar (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-0-520-24225-8.

183. Archaeological Survey of India, Annual report 1908–1909 p.129

184. Rapson, E. J. (1914). Ancient India. p. 157.

185. Sukthankar, Vishnu Sitaram, V. S. Sukthankar Memorial Edition, Vol. II: Analecta, Bombay: Karnatak Publishing House 1945 p.266

186. Salomon 1998, pp. 265–267

187. Brahmi Unicode (PDF). pp. 4–6.

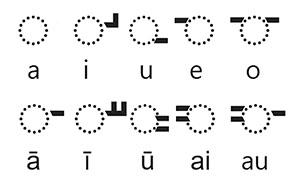

188. James Prinsep table of vowels

189. Seaby's Coin and Medal Bulletin: July 1980. Seaby Publications Ltd. 1980. p. 219.

190. "The three letters give us a complete name, which I read as Ṣastana (vide facsimile and cast). Dr. Vogel read it as Mastana but that is incorrect for Ma was always written with a circular or triangular knob below with two slanting lines joining the knob" in Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society. The Society. 1920.

191. Burgess, Jas (1883). Archaeological Survey Of Western India. p. 103.

192. Das Buch der Schrift: Enthaltend die Schriftzeichen und Alphabete aller ... (in German). K. k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. 1880. p. 126.

193. "Gupta Unicode" (PDF).

194. The "h" ( ) is an early variant of the Gupta script

195. Verma, Thakur Prasad (2018). The Imperial Maukharis: History of Imperial Maukharis of Kanauj and Harshavardhana (in Hindi). Notion Press. p. 264. ISBN 9781643248813.

196. Sircar, D. C. (2008). Studies in Indian Coins. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 376. ISBN 9788120829732.

197. Tandon, Pankaj (2013). Notes on the Evolution of Alchon Coins Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society, No. 216, Summer 2013. Oriental Numismatic Society. pp. 24–34. also Coinindia Alchon Coins (for an exact description of this coin type)

198. Smith, Janet S. (Shibamoto) (1996). "Japanese Writing". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 209–17. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

199. Evolutionary chart, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 7, 1838 [2]

200. Ledyard 1994, p. 336–349.

201. Daniels, Peter T. (Spring 2000). "On Writing Syllables: Three Episodes of Script Transfer" (PDF). Studies in the Linguistic Sciences. 30 (1): 73–86.

202. The Korean language reform of 1446 : the origin, background, and Early History of the Korean Alphabet, Gari Keith Ledyard. University of California, 1966:367–368, 370, 376.

Bibliography• Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

• Bühler, Georg (1898). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet. Strassburg K.J. Trübner.

• Deraniyagala, Siran (2004). The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective. Department of Archaeological Survey, Government of Sri Lanka. ISBN 978-955-9159-00-1.

• Falk, Harry (1993). Schrift im alten Indien: ein Forschungsbericht mit Anmerkungen (in German). Gunter Narr Verlag.

• Gérard Fussman, Les premiers systèmes d'écriture en Inde, in Annuaire du Collège de France 1988–1989 (in French)

• Hayashi, Takao (2003), "Indian Mathematics", in Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (ed.), Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences, 1, pp. 118–130, Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 976 pages, ISBN 978-0-8018-7396-6.

• Oscar von Hinüber, Der Beginn der Schrift und frühe Schriftlichkeit in Indien, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1990 (in German)

• Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5.

• Ledyard, Gari (1994). The Korean Language Reform of 1446: The Origin, Background, and Early History of the Korean Alphabet. University Microfilms.

• Masica, Colin (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

• Norman, Kenneth R. (1992). "The Development of Writing in India and its Effect upon the Pāli Canon". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens / Vienna Journal of South Asian Studies. 36 (Proceedings of the VIIIth World Sanskrit Conference Vienna): 239–249.

• Patel, Purushottam G.; Pandey, Pramod; Rajgor, Dilip (2007). The Indic Scripts: Palaeographic and Linguistic Perspectives. D.K. Printworld. ISBN 978-81-246-0406-9.

• Plofker, K. (2007), "Mathematics of India", in Katz, Victor J. (ed.), The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 685 pages, pp 385–514, pp. 385–514, ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

• Plofker, Kim (2009), Mathematics in India: 500 BCE–1800 CE, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-12067-6.

• Rocher, Ludo (2014). Studies in Hindu Law and Dharmaśāstra. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-78308-315-2.

• Salomon, Richard (1996). "Brahmi and Kharoshthi". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

• Salomon, Richard (1995). "On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

• Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

• Trautmann, Thomas (2006). Languages and Nations: The Dravidian Proof in Colonial Madras. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24455-9.

• Timmer, Barbara Catharina Jacoba (1930). Megasthenes en de Indische maatschappij. H.J. Paris.

Further reading• Buswell Jr., Robert E.; Lopez Jr., David S., eds. (2017). "Brāhmī". The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157863.

• Hitch, Douglas A. (1989). "BRĀHMĪ". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. pp. 432–433.

• Matthews, P. H. (2014). "Brahmi". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Linguistics (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967512-8.

• Red. (2017). "Brahmi-Schrift". Lexikon des gesamten Buchwesens Online (in German). Brill Online.