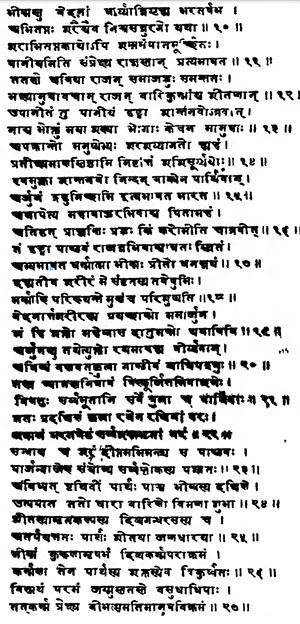

Remarks on the History of the Seven Roman Kings, Occasioned by Sir Isaac Newton’s Objections to the Supposed Two Hundred and Forty-Four Years’ Duration of the Regal State of Rome, from The Roman History From the Building of Rome to the Ruin of the Commonwealth, Illustrated with Maps

by N. Hooke, Esq.

A New Edition in Six Volumes

Vol. I

1823

Remarks on the History of the Seven Roman Kings, Occasioned by Sir Isaac Newton’s Objections to the Supposed Two Hundred and Forty-Four Years’ Duration of the Regal State of Rome

It is commonly admitted, upon the authority of the ancient chronologers, that the fall of Troy was about 676 years before the expulsion of Tarquin the last king of Rome, who was indisputably expelled about the year before Christ 508. But Sir Isaac Newton has, by many arguments, made it probable, that those chronologers have placed the taking of Troy* [Mr. Whiston, p. 971 of Authent. Rec. part 2. seems confident that Troy was taken just 1270 years before the Christian era, which computation (he says) agrees with the chronology of the author of the Life of Homer, supposed to be Herodotus.] near 300 years farther back than they ought to have done: and one of his arguments is drawn from the too long space of time supposed to be filled up by the reigns of only twenty-one kings in succession (fourteen at Alba, and seven at Rome). For in no country, of which the historical and chronological accounts are certain, is it found, that the like number of kings in succession reigned near so long as 676 years. And because most of the seven Roman kings were untimely slain, and one deposed, he thinks it not reasonable to believe that their reigns took up half the 244 years allotted to them by the Roman historians.

As the following remarks, offered in support of Sir Isaac Newton's conclusion, may happen to fall under the inspection of several persons who have not perused that great man's chronological work, it may to such perhaps be agreeable, if the remarks be introduced by some of his fundamental reasons for questioning the truth of the received chronology of ancient kingdoms in general, and of the Roman kingdom in particular.

'All nations, before they began to keep exact accounts of time, have been prone to raise their antiquities; and this humour has been promoted by the contentions between nations about their originals.

'Herodotus tells us, that the priests of Egypt reckoned from the reign of Menes to that of Sethon [He is supposed to be Mizraim the son of Cham, and grandson of Noah, and to have founded a kingdom in Egypt, A.M. 1772.—Ant. Chr. 2232. ], who put Senacherib to flight [†: Missing FN], 341 generations of men, and as many priests of Vulcan, and as many kings of Egypt; and that 300 generations make 10,000 years; for, saith Herodotus, three generations of men make 100 years: and the remaining forty and one generations 1340 years: and so the whole time from the reign of Menes to that of Sethon was 11,340 years. And by this way of reckoning, and allotting longer reigns to the gods of Egypt than to the kings which followed them, Herodotus tells us from the priests of Egypt, that from Pan to Amosis were 15,000 years, and from Hercules to Amosis 17,000.

'So also the Chaldeans boasted of their antiquity; for Callisthenes, the disciple of Aristotle, sent astronomical observations from Babylon to Greece, said to be of 1903 years' standing before the times of Alexander the Great. And the Chaldeans boasted farther, that they had observed the stars 473,000; and there were others who made the kingdoms of Assyria, Media, and Damascus, much older than the truth.

'Some of the Greeks called the times before the reign of Ogyges unknown, [Section: According to the old chronology, the flood of Ogyges happened 1796 years before the Christian era: but according to Sir I. N. little more than 1100 years. Short Chron. p. 10. 'In the beginning of that [the Persian] monarchy, Acusilaus made Phoroneus as old as Ogyges and his flood, and that flood 1020 older than the first Olympiad; which is above 680 years older than the truth.' Chron. of the Greeks, p. 45.] because they had no history of them; those between his flood and the beginning [‡: Missing FN] of the Olympiads fabulous, because their history was much mixed with poetical fables; and those after the beginning of the Olympiads historical, because their history was free from such fables. The fabulous ages wanted a good chronology, and so also did the historical, for the first sixty or seventy Olympiads.

'The Europeans had no chronology before the times of the Persian empire, and whatsoever chronology they now have of ancienter times hath been framed since by reasoning and conjecture.

'Plutarch tells us, that the philosophers anciently delivered their opinions in verse, as Orpheus, Hesiod, Parmenidcs, Xenophanes, Eropedocles, Thales.

'Solon wrote in verse, and all the seven wise men were addicted to poetry, as

Anaximenes affirmed. [||: Missing FN.]

'Till those days the Greeks wrote only in verse, and while they did so, there could be no chronology, nor any other history than such as was mixed with poetical fancies.

'Pliny, in reckoning up the inventors of things, tells us, that Pherecydes Scyrius taught to compose discourses in prose in the reign of Cyrus; and Cadmus Milesius to write history. And in another place he saith, that Cadmus Milesius was the first that wrote in prose.

'Josephus tells us, that Cadmus Milesius and Acusilaus were but a little before the expedition of the Persians against the Greeks: and Suidas calls Acusilaus a most ancient historian, and saith that he wrote genealogies out of tables of brass, which his father, as was reported, found in a corner of his house. Who hid them there may be doubted: for the Greeks had no public table or inscription older than the laws of Draco.

'Pherecydes Atheniensis, in the reign of Darius Hystaspis, or soon after, wrote of the antiquities and ancient genealogies of the Athenians in ten books; and was one of the first European writers of this kind, and one of the best; whence he had the name of Genealogus, and by Dionysius Halicarnassensis is said to be second to none of the genealogers.

'Epimenides (not the philosopher, but) an historian, wrote also of ancient genealogies: and

'Hellanicus (who was twelve years older than Herodotus) digested his history by the ages or successions of the priestesses of Juno Argiva. Others digested theirs by those of the archons of Athens, or kings of the Lacedemonians.

'Hippias the Elean published a breviary of the Olympiads, supported by no certain arguments, as Plutarch tells us:* [ ] he lived in the 105th Olympiad, [cross: ] and * was derided by Plato for his ignorance. This breviary seems to have contained nothing more than a short account of the victors in every Olympiad.

‘Then Ephorus the disciple of Isocrates formed a chronological history of Greece,* [ ] beginning with the return of the Heraclides into Peloponnesus, and ending with the siege of Porinthus in the twentieth year of Philip, the father of Alexander the Great, that is, eleven years before the fall of the Persian empire: but he digested things by generations, and the reckoning by the Olympiads, [Sir I.N. says the same in the introduction to his short Chronicle, and adds there these words, 'Nor does it appear that the reigns of kings were yet set down by numbers of years.'] or by any other era, was not yet in use among the Greeks.

‘The Arundelian marbles were composed sixty years after the death of Alexander the Great [An. 4. Olymp. 128.], and yet mention not the Olympiads, nor any other standing era, but reckon backwards from the time then present.

'But chronology was now reduced to a reckoning by years; and, in the next Olympiad,

‘Timaeas Siculus improved it: for he wrote a history, in several books, down to his own times according to the Olympiads; comparing the Ephori, the kings of Sparta, the archons of Athens, and the priestesses of Argos, with the Olympic victors, so as to make the Olympiads and the genealogies and successions of kings and priestesses, and the poetical histories, suit one another, according to the best of his judgment; and, where he left off, Polybius began, and carried on the history.

'Eratosthenes wrote above 100 years after the death of Alexander the Great. He was followed by Apollodorus, and these two have been followed ever since by chronologers.

‘But how uncertain their chronology is, and how doubtful it was reputed by the Greeks of those times, may be understood by these passages of Plutarch. “Some reckon Lycurgus,” saith he, “contemporary to Iphitus, and to have been his companion in ordering the Olympic festivals, amongst whom was Aristotle the philosopher; arguing from the Olympic disc, [N.B. In p. 58. Sir I.N. shows the fallacy of this argument. Iphitus, says he, did not restore all the Olympic games. He restored indeed the racing in the first Olympiad, Coroebus being victor. In the 14th Olympiad, the double stadium was added, Hypaenus being victor. And in the 18th Olympiad, the quinquertium and wrestling were added, Lampus and Erybatus, two Spartans, being victors; and the disc was one of the games of the quinquertium.] which had the name of Lycurgus upon it. Others supputing the times by the kings of Lacedemon, as Eratosthenes and Apollodorus, affirm that he was not a few years older than the first Olympiad.” He began to flourish in the 17th or 18th Olympiad, and at length Aristotle made him as old as the first Olympiad; and so did Epaminondas, as he is cited by Aelian and Plutarch: and then Eratosthenes, Apollodorus, and their followers, made him above 100 years older.'

[Mr. Winston accuses Sir I. Newton of not informing his readers how very difficult a thing it is to tell the age of Lycurgus; nor that Plutarch himself declares, “how every thing about Lycurgus is disputed; and, above all the rest, the time when he lived.” I cannot see any good ground for this quarrel with Sir I. N.; but I wonder that Mr. Whiston or any body should build much upon the authority of chronological canons, the framera of which were so destitute of authentic records as to be reduced to conjectures concerning the time when Lycurgus lived, than whose legislature there is not a more memorable event in the history of Greece. And it ought to be observed, that the uncertainty with regard to Lycurgus must be attended with a like uncertainty as to the times of the kings in the line of Procles; Lycurgus having been tutor to his nephew Charilaus the seventh king of that race. And it is remarkable that the chronologers have not pretended to know the number of years which each of those kings reigned, though they have marked the length of the several reigns of the kings in the line of Eurysthenes down to Polydorus the tenth king.]

In another place Plutarch tells us: 'The congress of Solon with Croesus some think they can confute by chronology. But a history so illustrious, and verified by so many witnesses, and which is more, so agreeable to the manners of Solon, and worthy of the greatness of his mind and of his wisdom, I cannot persuade myself to reject because of some chronological canons, as they call them, which hundreds of authors correcting, have not yet been able to constitute any thing certain, in which they could agree amongst themselves, about repugnances.

'Diodorus, in the beginning of his history, tells us, that be did not divine, by any certain space, the times preceding the Trojan war, because he had no certain foundation to rely upon: but from the Trojan war, according to the reckoning of Apollodorus, whom he followed, there were eighty years to the return of the Heraclides into Peloponnesus; and that from that period to the first Olympiad, there were 328 years, computing the times from the kings of the Lacedemonians. Apollodorus followed Eratosthenes, and both of them followed Thucydides in reckoning eighty years from the Trojan war to the return of the Heraclides: but in reckoning 328 years from that return to the first Olympiad, Diodorus tells us, that the times were computed from the kings of the Lacedemonians; and Plutarch tells us, that Apollodorus, Eratosthenes, and others, followed that computation: and since this reckoning is still received by chronologers, and was gathered by computing the times from the kings of the Lacedemonians, that is from their number, let us re-examine that computation.

'The Egyptians reckoned the reigns of kings equipollent to generations of men, and three generations to 100 years, as above; so did the Greeks and Latins, and accordingly they have made their kings reign one with another thirty and three years a-piece, and above.

'For they make the seven kings of Rome, who preceded the consuls, to have reigned 244 years, which is thirty-five years a-piece:

'And the first twelve kings of Sicyon, AEgialeus, Europs, &c. to have reigned 529 years, which is forty-four years a-piece:

'And the first eight kings of Argos, Inachus, Phoroneus, &c. to have reigned 371 years, which is above forty-six years a-piece:

'And between the return of the Heraclides into Peloponnesus, and the end of the first Messenian war, the ten kings of Sparta in one race,1. Eurysthenes,

2. Agis,

3. Echestratus,

4. Labotas,

5. Doryagus,

6. Agesilaus,

7. Archelaus,

8, Teleclus,

9. Alcamenes, and

10. Polydorus;

the nine in the other race,* [1. Procles, 2. Sous, 3. Eurypon, 4. Prytanis, 5. Eunomus, 6. Polydectes, 7. Charilaus, 8. Nicander, 9. Theopompus.] the ten kings of Messene. [1. Cresphontes, 2. Epytus, 3. Glaucus, 4. Isthmus, 5. Dotadas, 6. Sibotas, 7. Phintas, 8. Antiochus, 9. Euphaes. 10. Aristodemus.] and the nine of Arcadia, [1. Cypselus, 2. Olaus, 3. Buchalion, 4. Phialus, 5. Simus, 6. Pompus, 7. AEgineta, 8. Polymnestor, 9. AEchmis.] according to chronologers, took up 379 years: which is thirty-eight years a-piece to the ten kings, and forty-two years a-piece to the nine. And the five kings [following Polydorus] of the race of Eurysthenes, between the end of the first Messenian war, and the beginning of the reign of Darius Hystaspis; Eurycrates, Anaxander, Eurycrates II., Leon, Anaxandrides, reigned 202 years, which is above forty years a-piece.

‘Thus the Greek chronologers, who follow Timaes and Eratosthenes, have made the kings of their several cities, who lived before the times of the Persian empire, to reign about thirty-five or forty years a-piece, one with another; which is a length so much beyond the course of nature as is not to be credited. For by the ordinary course of nature, kings reign, one with another, about eighteen or twenty years a-piece: and if in some instances they reign, one with another, five or six years longer, in others they reign as much shorter: eighteen or twenty years is a medium.

'So the eighteen kings of Judah who succeeded Solomon reigned 390 years, which is one with another twenty-two years a-piece.

‘The fifteen kings of Israel after Solomon reigned 259 years, which is seventeen years and a quarter a-piece

‘The eighteen kings of Babylon; Nabonassar, &c. reigned 209 years, which is eleven years and two-thirds a-piece.

'The ten kings of Persia; Cyrus, Cambyses, &c. reigned 208 years, which is almost twenty-one years a-piece.

'The sixteen successors of Alexander the Great, and of his brother and son in Syria; Seleucus, Antiochus Soter, &c. reigned 244 years after the breaking of that monarchy into various kingdoms, which is fifteen years and a quarter a-piece.

'The eleven kings of Egypt; Ptolemaeus Lagi, &c. reigned 276 years, counted from the same period, which is twenty-five years a-piece.

'The eight in Macedonia; Cassander, &c. reigned 138 years, which is seventeen years and a quarter a-piece.

‘The thirty kings of England; William the Conqueror, William Rufus, &c. reigned 648 years, which is twenty-one years and a half a-piece.

'The first twenty-four kings of France; Pharamundus, &c. reigned 458 years, which is nineteen years a-piece.

‘The next twenty-four kings of France, Ludovicus Balbus, &c. 451 years, which is eighteen years and three quarters a-piece.

'The next fifteen, Philip Valesius, &c. 315 years, which is twenty-one years a-piece.

'And all the sixty-three kings of France, 1224 years, which is nineteen years and a half a piece.

'Generations from father to son may be reckoned, one with another, at about thirty-three or thirty-four years a-piece, or about three generations to 100 years: but if the reckoning proceed by the eldest sons, they are shorter, so that three of them may be reckoned at about seventy-five or eighty years; and the reigns of kings are still shorter, because kings are succeeded not only by their eldest sons, but sometimes by their brothers, and sometimes they are slain or deposed; and succeeded by others of an equal or greater age, especially in elective or turbulent kingdoms.

‘In the later ages, since chronology hath been exact, there is scarce an instance to be found of ten kings reigning any where in continual succession above 260 years; but Timaeus and his followers, and I think also some of his predecessors, after the example of the Egyptians, have taken the reigns of kings for generations, and reckoned three generations to 100, and sometimes to 120 years; and founded the technical chronology of the Greeks upon this way of reckoning. Let the reckoning be reduced to the course of nature, by putting the reigns of kings one with another, at about eighteen or twenty years a-piece: and the ten kings of Sparta by one race, the nine by another race, the ten kings of Messene, and the nine of Arcadia, above-mentioned, between the return of the Heraclides into Peloponnesus, and the end of the first Messenian war, will scarce take up above 180 or 190 years: whereas, according to chronologers, they took up 379 years.

'Cnronologers have [not only] lengthened the time, between the return of the Heraclides into Peloponnesus and the first Messenian war—they have also lengthened the time between that war and the Persian empire.

'For in the race of the Spartan kings, descended from Eurysthenes; after Polydorus reigned these kings:11. Eurycrates,

12. Anaxander,

13. Eurycrates II.

14. Leon,

15. Anaxandrides,

16. Cleomenes,

17. Leonides, &c.

‘And in the other race descended from Procles; after Theopompus [the ninth long] reigned these, Anaxandrides, Archidemus, Anaxileus, Leutychides, Hippocratides, Ariston, Demaratus, Leutychides II. &c. according to Herodotus. These kings reigned till the sixth year of Xerxes, in which Leonidas was slain by the Persians at Thermopylae; and Leutychides IL soon after, flying from Sparta to Tegea, died there.

‘The seven reigns of the kings of Sparta, which follow Polydorus. being added to the ten reigns above-mentioned, which began with that of Eurysthenes, make up seventeen reigns of kings between the return of the Heraclides into Peloponnesus and the sixth year of Xerxes: and the eight reigns following Theopompus, being added to the nine reigns above-mentioned, which began with that of Procles, made up also seventeen reigns, and these seventeen reigns, at twenty years a-piece one with another, amount unto 340 years. Count these 340 years upwards from the sixth year of Xerxes, and one or two years more for the war of the Heraclides, and the reign of Aristodemus, the father of Eurysthenes and Procles; and they will place the return of the Heraclides into Peloponnesus 159 years after the death of Solomon, and forty-six years before the first Olympiad,* [ ] in which Coroebus was victor. But the followers of Timaeus have placed this return 280 years earlier.* [ ] Now this being the computation upon which the Greeks, as you have heard from Diodorus and Plutarch, have founded the chronology of their kingdoms, which were ancienter than the Persian empire; that chronology is to be rectified by shortening the times which preceded the death of Cyrus, in the proportion of almost two to one; for the times which follow the death of Cyrus are not much amiss.'

[The truth of Sir I. N.'s computation with regard to the reigns of the seventeen kings of Sparta, of whom Leonidas was the last, seems to be well supported by the space of time filled up by the reigns of the thirteen kings (of the same line) who reigned in succession after Leonidas.

Leonidas was slain in the year before Christ, 480.

Cleomenes, the last of the thirteen kings who reigned after him, being expelled Peloponnesus, killed himself in Egypt (as Petavius hath shown [‡ Missing FN.]), in 219 before Christ.

The years between the deaths of these two kings are 261, so that the thirteen kings in succession from Leonidas reigned but about twenty years a-piece one with another.]

'As for the chronology of the Latins, that is still more uncertain [than the chronology of the Greeks]. Plutarch represents great uncertainties in the originals of Rome, [§: Missing FN.] and so doth Servius [||: Missing FN.] The old records of the Latins were burnt by the Gauls 120 years after the Regifuge, and sixty-four years before the death of Alexander the Great: [ ¶: Missing FN.] and Quintus Fabius Pictor, the oldest historian of the Latins, lived 100 years later than that king, and took almost all things

[concerning tne originals of Rome] from Diocles Peparethius, a Greek,

‘When the Romans conquered the Carthaginians, the archives of Carthage came into their hands. And thence Appian, in his History of the Punic Wars, tells in round numbers that Carthage stood 700 years; and Solinus adds the odd number of years [thirty-seven] in these words, “Adrymeto atque Carthagini author est a Tyro populus. Urbem istam, ut Cato in oratione senatoria autumat, cum rex Hiarbas rerum in Libya potiretur, Elissa mulier extruxit, domo Phoenix, et Carthadam dixit, quod Phoenicum ore exprimit civitatem novam; mox sermone verso Carthago dicto est, quae post annos septingentos triginta septem exciditur quam fuerat extructa.”

'Elissa was Dido, and Carthage was destroyed in the consulship of Lentulus and Mummius, in the year of the Julian period 4568; from whence count backward 737 years, [*: Missing FN.] and the eucaenia or dedication of the city will fall upon the sixteenth year of Pygmalion the brother of Dido, and king of Tyre. She fled in the seventh year of Pygmalion, but the era of the city began with its encaenia.

'Now Virgil and his scholiast Servius, who might have some things from the archives of Tyre and Cyprus, as well as from those of Carthage, relate that Teucer came from the war of Troy to Cyprus, in the days of Dido, a little before the reign of her brother Pygmalion; and in conjunction with her father, seized Cyprus, and ejected Cinyras: and the marbles say, that Teucer came to Cyprus seven years after the destruction of Troy, and built Salamis; and Apollodorus, that Cinyras married Metharme the daughter of Pygmalion, and built Paphos. Therefore, if the Romans, in the days of Augustus, followed not altogether the artificial chronology of Eratosthenes, but had those things from the records of Carthage, Cyprus, or Tyre; the arrival of Teucer at Cyprus will be in the reign of the predecessor of Pygmalion, and by consequence the destruction of Troy, about seventy-six years later than the death of Solomon.

'Dionysius Halicarnassensis tells us that in the time of the Trojan war Latinus was king of the Aborigines in Italy, and that in the sixteenth age after that war Romulus built Rome. By ages he means reigns of kings; for after Latinus he names sixteen kings of the Latins, the last of which was Numitor, in whose days Romulus built Rome: for Romulus was contemporary to Numitor, and after him Dionysius and others reckon six kings more over Rome, to the beginning of the consuls. Now these twenty and two reigns, at about eighteen years to a reign one with another, for so many of these kings were slain, took up 396 years; which counted back from the consulship of Junius Brutus and Valerius Publicola, the two first consuls, place the Trojan war about seventy-eight years after the death of Solomon.

'When the Greeks and Latins were forming their technical chronology, there were great disputes about the antiquity of Rome; the Greeks made it much older than the Olympiads: some of them said it was built by AEneas; others, by Romus, the son or grandson of AEneas; others, by Romus, the son or grandson of Latinus, king of the Aborigines; others, by Romus, the son of Ulysses, or of Ascanius, or of Italus: and some of the Latins at first fell in with the opinion of the Greeks, saying that it was built by Romulus the son or grandson of AEneas. Timaeus Siculus represented it built by Romulus the grandson of AEneas, above 100 years before the Olympiads, and so did Naevius the poet, who was twenty years older than Ennius, and served in the first Punic war, and wrote the history of that war.

'Hitherto nothing certain was agreed upon, but about 140 or 150 years after the death of Alexander the Great, they began to say that Rome was built a second time by Romulus, in the fifteenth age after the destruction of Troy: by ages they meant reigns of the kings of the Latins at Alba, and reckoned the first fourteen reigns at about 432 years, and the following reigns of the seven kings of Rome at 344 years, both which numbers made up the time of about 676 years from the taking of Troy, according to these chronologers; but are much too long for the course of nature: and by this reckoning they placed the building of Rome upon the sixth or seventh Olympiad; Varro* [If this be not an error of the press, yet doubtless Sir Isaac Newton meant to write Cato, not Varro. Varro placed the foundation of Rome in the third year of the 6th Olympiad [Ant. Chr. 753], Cato in the first year of the 7th [Ant. Chr. 751). These two writers agreed in giving 244 years to the regal state of Rome, but, as they fixed the aera of the city by reckoning backward, and counted the years of the republic by the annual magistracies, and as Varro, in this way of counting, gave to the republic two years more than Cato; he of course placed the building of Rome two years farther back than Cato had done. There were three dictatorships, to each of which Varro allotted a whole year, which dictatorships Cato had considered as only superseding so many consulships, and therefore reckoned each consulship and the dictatorship that superseded it as filling but one year. And this would have made Varro's reckoning, upon the whole, exceed Cato's by three years; but Varro, by placing in one and the same year the third decemvirate and the succeeding consulship, to which magistracies Cato allotted distinct years, the reckoning of Varro, upon the whole, exceeded that of Cato by two years only. The Capitoline marbles, with regard to the three dictatorships and the third decemvirate, reckon like Varro; but as they give only 243 years to the regal state of Rome, their chronology upon the whole has a year less than Varro's, and a year more than Cato's. See notes Sur Chron. Grecque-Rom. selon D. Hal. by the French translator of Dionysius, p. 34.] placed it on the first year of the seventh Olympiad, and was therein generally followed by the Romans; but this can scarce be reconciled to the course of nature: for I do not meet with any instance in all history, since chronology was certain, wherein seven kings, most of whom were slain, reigned 244 years in continual succession.

‘The fourteen reigns of the kings of the Latins, at twenty years a-piece one with another, amount unto 280 years, and these years counted from the taking of Troy end in the 38th Olympiad: and the reigns of the seven kings of Rome, four or five of them being slain, and one deposed, may at a moderate reckoning amount to fifteen or sixteen years a-piece one with another: let them be reckoned at seventeen years a-piece, and they will amount unto 119 years; which, being counted backwards from the Regifuge, And also in the 38th Olympiad: and by these two reckonings Rome was built in the 38th Olympiad, or thereabout.

'The 280 years and the 119 years together make up 399 years; and the same number of years arises by counting the twenty and one reigns at nineteen years a-piece; and this being the whole time between the taking of Troy and the Regifuge, let these years be counted backward from the Regifuge An. 1. Olymp. 68. [*: Missing FN.] and they will place the taking of Troy about seventy-four years after the death of Solomon.' [Which death of Solomon Sir Isaac Newton places 979 years before the Christian aera; so that the fall of Troy, soon after which AEneas began his voyages, will be about 905 years before that aera; and as Sir Isaac makes the flight of Dido from Tyre to be Ant. Chr. 892. there were, according to this computation, but about thirteen years between these two last-mentioned events.]

Mr. Whiston, in his treatise entitled a Confutation of Sir Isaac Newton's Chronology, observes, (p. 987.) that

“In England we have had nine successive reigns at almost thirty years a-piece, from Henry I. to Edward III.

“And twelve at almost twenty-eight years a-piece, from William the Conqueror to Richard II.

“And the French have had six reigns together at almost forty years a-piece, from Robert to Philip II.

“And eight reigns at above thirty-five years a-piece, from Robert to Louis IX.

“'And ten reigns at almost thirty-three years a-piece, from Robert to Philip IV. all inclusive, as these tables will show.

Kings of England.

1. William the Conqueror: 21

2. William Rufus: 13

3. Henry I: 35

4. Stephen: 19

5. Henry II: 35

6. Richard I: 11

7. John: 17

8. Henry III: 56

9. Edward I: 34

10. Edward II: 19

11. Edward III: 51

12. Richard II: 22

_______

Total: 12)333 (27-3/4

Kings of France.

1. Rupert or Robert: 45

2. Henry I: 28

3. Philip I: 48

4. Lewis VI: 29

5. Lewis VII: 43

6. Philip II: 43

7. Lewis VIII: 3

8. Lewis IX: 55

9. Philip III: 15

10. Philip IV: 29

_______

Total: 10) 327 (32-1/4

From these examples Mr. Whiston infers, that we ought not to reject or alter the series of the reigns of the twelve kings of Macedonia, from Caranus, of the Heraclidae, to Archelaus, which twelve reigns take up 415 years. 12) 415 (34-1/2. Nor the series of the reigns of the eight last of the Latin kings, from Amulius to Tarquin the Proud, which takes up 286 years. 8) 286 (35-1/4. Which reigns of Macedonian and Latin kings, he observes, are of all he had before marked (in several series of ancient long reigns) the longest in proportion, because they began after human life was reduced to its present standard.

Now I think it must be granted, that the examples which Mr. Whiston has produced of long reigns in succession, both in England and in France, would be sufficient to make it credible, that the seven kings of Rome reigned as long as they are reported to have done, if there were no objection to this report, but its being uncommon to find, in authentic and undisputed history, seven kings reigning, in succession, thirty-five years a-piece one with another. But here it may be proper to consider,

I. That we have no better authority for the long reigns of the seven kings of Rome than for the long reigns of the fourteen kings of Alba, their predecessors; and there is no instance, since chronology was certain, of twenty-one kings in succession reigning near thirty-two years a-piece, one with another, as the twenty-one kings in question are represented to have done.

Mr. Whiston, as we see above, has given us ten kings of France in succession, who reigned 327 years, or thirty-two years and three-quarters a-piece.

I think he has stretched the reign of Robert ten or eleven years beyond its true length. But, letting that pass, if to these ten kings we add the five that preceded them, and the six that followed them, to make the number twenty-one, we shall find that the twenty-one kings reigned but about twenty-one years a-piece one with another.

For Raoul, the first of the twenty-one, began to reign An. Dom. 923, and Jean II. the last of the twenty-one, died in 1363, the whole space 440 years.

If to the ten kings we add the eleven that preceded them, the reigns of the twenty-one will be still shorter.

Indeed, if to the ten we add the eleven that followed them, the twenty-one reigns amount to near twenty-four years a-piece one with another. But this is far short of thirty-two years a-piece, to which the twenty-one reigns of the Latin kings amount, within a trifle, according to Bishop Lloyd's tables, cited by Mr. Whiston.

So likewise, though we have had in England twelve successive reigns at almost twenty-eight years a-piece, from William the Conqueror to Richard II. yet, if to those twelve we add the nine reigns which followed that of Richard II. we shall find that the twenty-one kings did not reign quite twenty-three years a-piece one with another.

II. It may be farther observed, that the old chronology, which makes the reigns of twenty-one Latin kings fill up a space of time so much longer than the reigns of the same number of kings of any country have ever done since chronology was certain, does in like manner make the reigns of every series of kings of the most ancient kingdoms exceed, in duration, what the common course of nature, as known by true history, admits; which universal excess affords a probable argument, that the old chronology was wholly artificial, and not founded on authentic records or monuments.

When I say every series of kings, it might perhaps be expected that I should except the long successions of kings in Egypt (from the time of Mizraim the son of Ham), to which numerous kings short reigns are assigned by the old chronology:* [Mr. Whiston, in p. 975, makes the following observation: “Manetho, when he speaks of the several dynasties of Egypt, or of the several succession of collateral kingdoms, mentions the principal successions as extending to 113 generations in 3555 years: and implies, that the first sixteen, which were chiefly before the deluge, were more than equal to the other ninety-seven: those sixteen containing no fewer than 1985 years; and the ninety-seven no more than 1570 years: the former allowing to each generation or succession 124 years: as the duration of human life before the deluge well admitted; and (the Chaldean succession at Babylon in Abydenus and Berosus equally admitted also) while the latter allows but a little above sixteen years to such a succession, till the days of Alexander the Great: which last small number might yet well agree to those latter ages of the kingdom of Egypt, which might be subject to great disturbances and changes of government all along.”] but I consider those series of Egyptian monarchs as fabulous. For indeed the short reigns, assigned to them, are alone almost a demonstrative proof, that the greater number of the kings, in those series, never existed, or at least not in line of succession; as I shall show hereafter.

III. That most of the seven kings of Rome being slain, and one deposed, there arises hence a great improbability of their reigning thirty-five years a-piece, one with another.

IV. And lastly, that in the accounts given us of those seven kings, there are some particulars by which the historians discover the uncertainty of their chronology, and some that seem entirely to refute it, as the following remarks will show.