VII. On the ancient Geography of India.

by Lieut. Col. F. Wilford

Asiatick Researches; or Transactions of the Society, Instituted in Bengal, For Enquiring into the History and Antiquities, the Arts, Sciences, and Literature, of Asia, Volume the Fourteenth

1822

Pgs. 373-470

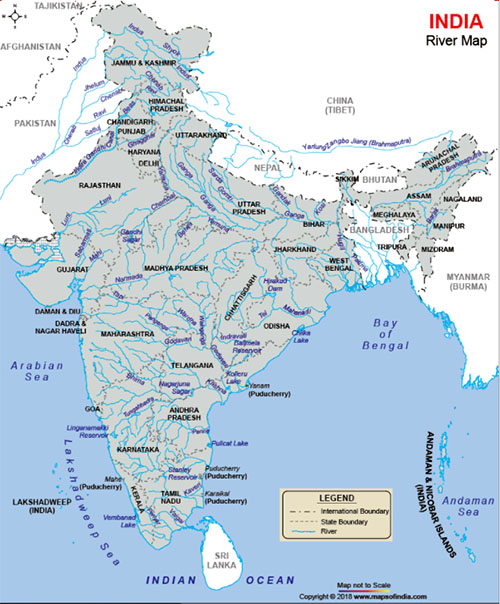

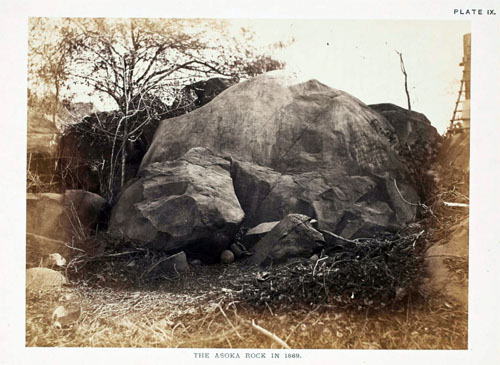

Finally; the classical authors concur in making Palibothra a city on the Ganges, the capital of Sandrocoptus. Strabo, on the authority of Megasthenes, states that Palibothra is situated at the confluence of the Ganges and another river, the name of which he does not mention. Arrian, possibly on the same authority, calls that river the Erranoboas, which is a synonime of the Sone. In the drama, one of the characters describes the trampling down of the banks of the Sone, as the army approaches to Pataliputra; and Putaliputra, also called Kusumapura, is the capital of Chandragupta. There is little question that Pataliputra and Palibothra are the same, and in the uniform estimation of the Hindus, the former is the same with Patna. The alterations in the course of the rivers of India, and the small comparative extent to which the city has shrunk in modern times, will sufficiently explain why Patna is not at the confluence of the Ganges and the Sone, and the only argument, then, against the identity of the position, is the enumeration of the Erranoboas and the Sone as distinct rivers by Arrian and Pliny: but their nomenclature is unaccompanied by any description, and it was very easy to mistake synonimes for distinct appellations. Rajamahal, as proposed by Wilford, and Bhagalpur, as maintained by Franklin, are both utterly untenable, and the further inquiries of the former had satisfied him of the error of his hypothesis. His death prevented the publication of an interesting paper by him on the site of Palibothra, in which he had come over to the prevailing opinion, and shewn it to have been situated in the vicinity of Patna.* [Asiatic Researches, vol. xiv. p. 380.]

-- The Mudra Rakshasa, or The Signet of the Minister. A Drama, Translated from the Original Sanscrit, Select Specimens of the Theatre of the Hindus, Translated from Original Sanskrit, in Two Volumes, Vol. II, by Horace Hayman Wilson, 1835

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS.

A FEW years after my arrival in India, I began to study the ancient history, and geography of that country; and of course, endeavoured to procure some regular works on the subject: the attempt proved vain, though I spared neither trouble, nor money, and I had given up every hope, when, most unexpectedly, and through mere chance, several geographical tracts in Sanscrit, fell into my hands. I very much regret, that they did not make their appearance somewhat earlier; for time passes away heedless of our favourite pursuits.

In some of the Puranas, there is a section called the Bhuvana-cosa, a magazine, or Collection of mansions: but these are entirely mythological, and beneath our notice.

Bhuchanda, or Bhuvana Cosa, a section of the Puranas on geography, VIII. 268, 287.

-- Index to the First Eighteen Volumes of the Asiatic Researches, Or, Transactions of the Society

Instituted in Bengal for Enquiring Into the History and Antiquities, the Arts, Sciences and Literature of Asia, by Asia Society, 1835

Besides those in the Puranas, there are other geographical tracts, to several of which is given the title of Cshetra-samasa, or collection of countries; one is entirely mythological, and is highly esteemed by the Jainas; another in my possession, is entirely geographical, and is a most valuable work.

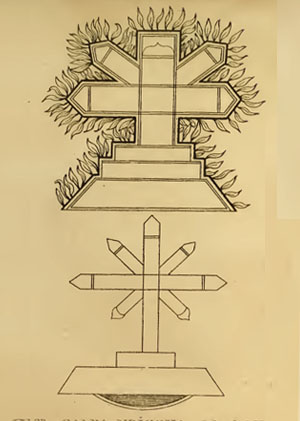

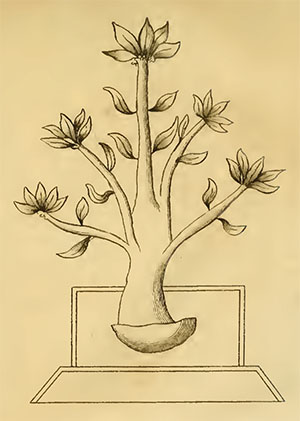

VI. The cross, though not an object of worship among the Bauddhas, is a favourite emblem and device with them. It is exactly the cross of the Manicheans, with leaves and flowers springing from it, and placed upon a mount Calvary, as among the Roman Catholics. They represent it various ways; but the shaft with the cross bar, and the Calvary remain the same. The tree of life and knowledge, or the Jambu tree, in their maps of the world, is always represented in the shape of a Manichean cross, eighty-four Yojanas (answering to the eighty-four years of the life of him who was exalted upon the cross), or 423 miles high, including the three steps of the Calvary.Calvary, or Golgotha was, according to the canonical Gospels, a site immediately outside Jerusalem's walls where Jesus was crucified.

The Gospels use the Koine term Kraníon or Kraniou topos when testifying to the place outside Jerusalem where Jesus was crucified. E.g., Mark 15:22 (NRSV), "Then they brought Jesus to the place called Golgotha (which means: 'the place of a skull')." 'Kraníon is often translated as 'skull' in English, but more accurately means cranium, the part of the skull enclosing the brain. In Latin, it is rendered Calvariae Locus, from which the English term Calvary derives.

Its traditional site, identified by Queen Mother Helena, mother of Constantine the Great, in 325, is at the site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. A 19th-century suggestion places it at the site now known as 'The Garden Tomb' on Skull Hill, some 500 m (1,600 ft) to the north, and 200 m (660 ft) north of the Damascus Gate.

-- Calvary, by Wikipedia

This cross, putting forth leaves and flowers, (and fruit also, as I am told) is called the divine tree, the tree of the gods, the tree of life and knowledge, and productive of whatever is good and desirable, and is placed in the terrestrial Paradise. Agapius, according to Photius,* [Phot. Biblioth. p. 403.] maintained, that this divine tree in Paradise, was Christ himself. In their delineations of the heavens, the globe of the earth is filled up with this cross and its Calvary. The divines of Tibet place it to the S.W. of Meru, towards the source of the Ganges. The Manicheans always represented Christ crucified upon a tree among the foliage. The Christians of India, and of St. Thomas, though they did not admit of images, still entertained the greatest veneration for the cross. They placed it on a Calvary, in public places, and at the meeting of cross roads; and it is said, that even the heathen Hindus in these parts paid also great regard to it. I have annexed the drawings of two crosses, from a book entitled the Cshetra-samasa, lately given to me by a learned Bauddha, who is visiting the holy places in the countries bordering upon the Ganges.* [Plate 2] There are various representations of this mystical symbol, which my friend the Jati could not explain to me; but says, that the shaft and the two arms of the cross remain invariably the same, and that the Calvary is sometimes omitted. It becomes then a cross, with four points, sometimes altered into a cross cramponne, as used in heraldry.

In the second figure there are two instruments depicted, the meaning of which my learned friend, the Jati, could not explain. Neither did he know what they were intended to represent; but, says he, they look like two spears : and indeed they look very much like the spear and reed, often represented with the cross. The third figure represents the same tree, but somewhat nearer to its natural shape. When it is represented as a trunk without branches, as in Japan, it is then said to be the seat of the supreme ONE. When two arms are added, as in our cross, the Trimurti is said to be seated there. When with five branches, the five Sugats, or grand forms of Buddha, are said to reside upon there. Be this as it may, 1 cannot believe the resemblance of this cross and Calvary, with the sign of our redemption, to be merely accidental. I have written this account of the progress of the Christian religion in India, with the impartiality of an historian, fully persuaded that our holy religion cannot possibly receive any additional lustre from it.

Volume 10, Plate 2. The Calpa-Vricsha of the Bauddhas which is the same with the cross of the Manicheans.

-- II. An Essay on the Sacred Isles in the West, with other Essays connected with that Work, by Captain F. Wilford. Essay V. Origin and Decline of the Christian Religion in India, Asiatic Researches, Volume 10, 1811

It would also be useful to obtain some of the modern treatises on geography which exist, it is said, in several countries of India, notably among the Djaïnas of Malvah and Gudjérat; we know that Wilford had several works of this kind in his hands, and that he especially made great use, for his last works, of the Samâsa-Kchetra (Collection of Countries), a prescriptive [relating to the imposition or enforcement of a rule or method.] treatise on geography written in the seventeenth century. However modern these works may be, and however mixed they may be with fables and errors, one should find in them good indications, from which European criticism will be able to turn to good account. Wilford also speaks of two ancient treatises on Sanskrit geography, one of the fifth-sixth century of our era, the other of the tenth-sixth century; the discovery of one or the other of these works would surely be a very useful acquisition.

-- Etuden Sur La Geographie Et Les Populations Primitives Du Nord-Ouest De L'Inde D'Apres Les Hymnes Vediques Precedee D'Un Apercu De L'Etat Actuel Des Etudes Sur L'Inde Ancienne, by Par M. Vivien De Saint-Martin, 1855 (Study on the Geography and the Primitive Populations of North-West India According to the Vedic Hymns Preceded by an Overview of the Current State of Studies on Ancient India, by M. Vivien De Saint-Martin, 1855)

There is also the Trai-locya-derpana, or mirror of the three worlds: but it is wholly mythological, and written in the spoken dialects of the countries about Muttra. St. Patrick is supposed to have written such a book, which is entitled de tribus Habitaculis, and this was also entirely mythological.

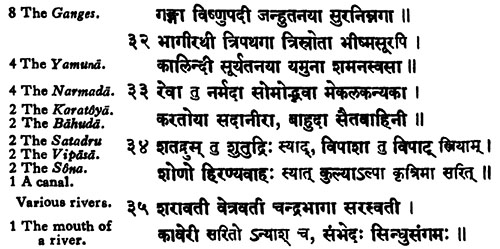

There are also lists of countries, rivers and mountains, in several Puranas, and other books; but they are of little or no use, being mere lists of names, without any explanation whatever. They are very incorrectly written, and the context can be of no service, in correcting the bad spelling of proper names. These in general are called Desamala, or garlands of countries; and are of great antiquity: they appear to have been known to Megasthenes, and afterwards to Pliny.*

Of the Manners of the Indians.

The Indians all live frugally, especially when in camp. They dislike a great undisciplined multitude, and consequently they observe good order. Theft is of very rare occurrence. Megasthenes says that those who were in the camp of Sandrakottos, wherein lay 400,000 men, found that the thefts reported on any one day did not exceed the value of two hundred drachmae, and this among a people who have no written laws, but are ignorant of writing, and must therefore in all the business of life trust to memory.

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A., Principal of the Government College, Patna, Member of the General Council of the University of Edinburgh, Fellow of the University of Calcutta, With Introduction, Notes and Map of Ancient India, Reprinted (with additions) from the "Indian Antiquary," 1876-77

[Consult the 20th Chapter of the 6th Book, in which the account of so many countries all over India, cannot be the result of the travels of several individuals, but must be extracted from such lists. In the 17th Chapter of the same book, Pliny says that Seneca, in his attempt towards a description of India, had mentioned no less than sixty rivers, one hundred and twenty nations or countries, besides mountains, and in the latter part of the said chapter, out of this account of Seneca, he gives us the names of several mountains, nations and rivers. It is my opinion that in the times of Pliny and Ptolemy, they had a more full and copious geographical account of India, than we had forty years ago. Unluckily through the want of regular itineraries end astronomical observations, their longitudes and latitudes were only inferred; and this alone was sufficient to throw the whole of their geographical information, into a shapeless and inextricable mass of confusion.

Real geographical treatises do exist: but they are very scarce, and the owners unwilling, either to part with them, or to allow any copy to be made, particularly for strangers. For they say, that it is highly improper, to impart any knowledge of the state of their country, to foreigners; and they consider these geographical works as copies of the archives of the government of their country. Seven of them have come to my knowledge, three of which are in my possession. The two oldest are the Munja-prati-desa-vyavastha, or an account of various countries, written by Raja Munja, in the latter end of the ninth century: it was revised and improved by Raja Bhoja his nephew, in the beginning of the tenth, it is supposed; and this new edition was published under the name of Bhoja-prati-desa-vyavastha. These two treatises, which are voluminous, particularly the latter, are still to be found, in Gujarat, as I was repeatedly assured, by a most respectable Pandit, a native of that country, who died some years ago, in my service. I then applied to the late Mr. Duncan, Governor of Bombay, to procure those two geographical tracts, but in vain: his enquiries however confirmed their existence. These two are not mentioned in any Sanscrit book, that I ever saw. The next geographical treatise, is that written by order of the famous Buccaraya or Bucca-sinha, who ruled in the peninsula in the year of Vicramaditya, 1341, answering to the year 1285 of our era.

Bukka Raya I (reigned 1356–1377 CE) was an emperor of the Vijayanagara Empire from the Sangama Dynasty. He was a son of Bhavana Sangama, the chieftain of a pastoralist community Shepard lineage.

The early life of Bukka as well as his brother Hakka (also known as Harihara I) are relatively unknown and most accounts of their early life are based on various theories.

Bukka [Raya I], by Wikipedia

It is mentioned in the commentary on the geography of the Maha-bharata, and it is said, that he wrote an account of the 310 Rajaships of India, and Palibothra is mentioned in it. I suspect that this is the geographical treatise called Bhuvana-sagara, or sea of mansions, in the Dekhin.

A passage from it, is cited by professor Sig. Bayer, in which is mentioned the town of Nisadaburam, in the Tamul dialect,* [In which da is the mark of the possessive case.] but in Sanscrit Nuhushapur, or Naushapur, from an ancient and famous king of that name more generally called Deva-nahusha, and Deo-naush, in the spoken dialects. He appears to be the Dionysius, of our ancient mythologists, and reigned near mount Meru, now Mar-coh, to the S. E. of Cabul.

The fourth is a commentary on the geography of the Maha-bharat, written by order of the Raja of Paulastya in the peninsula, by a Pandit, who resided in Bengal, in the time of Hussein-shah, who began his reign in the year 1489[???]. It is a voluminous work, most curious, and interesting. It is in my possession, except a small portion towards the end, and which I hope to be able to procure. Palibothra is mentioned in it.

In Hindu mythology, Pulastya was one of the ten Prajapati or mind-born sons of Brahma, (Manas Putra) and one of the Saptarishis (Seven Great Sages Rishi) in the first Manvantara.

-- Pulastya, by Wikipedia

Ala-ud-din Husain Shah r. 1494–1519) was an independent late medieval Sultan of Bengal, who founded the Hussain Shahi dynasty. He became the ruler of Bengal after assassinating the Abyssinian Sultan, Shams-ud-Din Muzaffar Shah, whom he had served under as wazir. After his death in 1519, his son Nusrat Shah succeeded him. The reigns of Husain Shah and Nusrat Shah are generally regarded as the "golden age" of the Bengal sultanate...

The reign of Husain Shah witnessed a remarkable development of Bengali literature. Under the patronage of Paragal Khan, Husain Shah's governor of Chittagong, Kabindra Parameshvar wrote his Pandabbijay, a Bengali adaptation of the Mahabharata. Similarly, under the patronage of Paragal's son Chhuti Khan, who succeeded his father as governor of Chittagong, Shrikar Nandi wrote another Bengali adaptation of the Mahabharata.

-- Alauddin Husain Shah, by Wikipedia

There are also a few WORKS professing to DEAL WITH GEOGRAPHY. Mr. Wilford has long ago pointed out (Asiatick Researches, XIV. pp. 374-380), the existence of the following:— (1) Munja-pratidesa [x]-vyavastha, (2) Bhoja-pratidesa-vyavastha (a revised edition of 1), (3) Bhuvana-Sagara, (4) A Geography written at the command of Bukkaraya, (5) A commentary on the Geography of the Mahabharata written by order of the Raja of Paulastya (?Paurastya?) by a Pandit in the time of Hussein Shah (1489) — a voluminous work. A MS. acquired by Mr. Wilford once formed a part of the Library of Fort William College: it is now in the Government Sanskrit College Library, Calcutta. A detailed description,* [Gazetteer literature in Sanskrit.] of this MS. has been given by M.M.H.P. Sastri in the Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society (1919). Prof. Pulle has mentioned (in pp 13-15 in his Studi Italiani di Filologia Indo-lranica, vol IV.) the existence of the following geographical works in the Library of the Nazionale centrale di Firenze (Florence, in Italy):— (5) Lokapraksa ([x]) of Kshemendra (the celebrated Kasmirian writer): the MS. consists of 782 pages and it is profusely illustrated. Prof Pulle has reproduced two of its figures in his Studi. (6) Three MSS. of Kshetra Samasa, a Jaina work — with two different commentaries, (7) A MS. of Kshetra Samasa Prakarana, (8) Four MSS. of Samgha- yani of Chandrasuri with two commentaries: one of the MSS. is illustrated, (9) A Laghu-Samghayani. He has also pointed out the mention of Kshetra Samasa of Jina Bhadra (1457-1517) in Kielhorn's Report (1880-1), of (10) Loghu Kshetra Samasa of Ratnasekhara in Weber's Cat. (No. 1942), of (11) Trailokya dipika and (12) Trailokya Darpana quoted by Wilford. Besides the above, (13) a Jama Tittha Kappa, and (14) Tristhaliactu dealing with the topography of Prayaga are also known.

St Martin [de Louis vivien de Saint-Martin] [Etat actuel des etudes sur l'Inde ancienne, p. xiii. (Google translate: Current state of studies on ancient India)] characterized the works mentioned by Wilford to be "imposture literature" without sufficiently examining them. Be they "imposture" or not, they have not yet been sufficiently examined.[!!!]

-- Cunningham's Ancient Geography of India, Edited With Introduction and Notes by Surendranath Majumdar Shastri, M.A., Premchand Raychand Scholar, Reader, Patna University, 1924

In this set of recent publications on Brahmanic India, geography had lagged far behind. Many particular points have been touched upon in some of the great works which Europe has seen appear for twenty years, especially in those of M. Wilson and M. Lassen; there are indications of detail and happy comparisons; a great number of facts and identifications can also be drawn from the innumerable memoirs scattered in the special journals and in the academic collections of India and Europe: but, until now, the subject had not been approached in a work together. This work, which alone can reconstitute in a regular body the Sanskrit geography of India, became however each day of a more urgent necessity; there is not a question of history or archaeology where this necessity does not make itself keenly felt. The first condition in any research of this nature is to be firmly fixed on the theater of events; otherwise the texts bring to mind only a floating and confused image.

Studies on the geography of ancient India have long been limited to the notions provided by Greek and Latin writers. Until the end of the last century, Sanskrit India did not yet exist. We knew of the past of this great peninsula only what our own classical authors have transmitted to us, according to the original historians of Alexander the Great and his immediate successors, and also according to the relations of which the commercial relations of Roman Egypt with the East became the occasion. The researches of d'Anville (1783 and 1775), the first who seriously attempted to bring together classical indications with modern notions; those of Rennell (1783 to 1793), of Mannert (1797), of Wahl (1805), of Dr. Vincent (1807) and of M. Gossellin (1789 to 1813), did not come out of this circle. Already, however, in his discourses on the sciences and literature of the Asiatic nationalities, William Jones, the famous founder of the Bengal Society, had hinted at the unknown resources which Brahmanical literature could furnish for the study of ancient India, and he had endeavored, not without success, to carry the English Orientalists in this direction. In 1801, in the sixth volume of Asiatic Researches1 [Introd. p. iv.], the Asiatic Society of Calcutta reported among the desiderata of Indian studies "a Catalog of the names of towns, countries, provinces, rivers and mountains taken from the Castras and the Puranas, with the correspondence of modern names." It asked also research on this question both historical and geographical: "What were the geographical and political divisions of the country before the Muslim invasion?" What the Society demanded from then on was nothing less than the complete restitution of the Sanskrit geography of India. But this task, if it was not beyond the strength of those who found themselves in a position to undertake it, exceeded the resources with which such an enterprise could then surround itself; for studies of comparative geography must be based above all on complete knowledge of the locality, and the topographical survey of the peninsula was barely begun at that time.

Colonel Wilford was unfortunately the only member of the Calcutta Society who entered into this direction of geographical research pointed out by William Jones. Wilford was read and zealous; and, if he had been endowed with a critical sense, which he entirely lacked, he could have rendered real service to Indian studies. But the incredible aberrations to which he so often lets himself be carried away (not to mention the literary impostures of his pundits, of which he was the first victim), remove all serious value from his works, and only allow the facts to be received with extreme reserve, and reconciliations, which have not been audited by other authorities.A far more promising approach to the problem, indeed a short cut, seemed to be heralded in a letter to Jones from Lieutenant Francis Wilford, a surveyor and an enthusiastic student of all things oriental, who was based at Benares. Jones had been sent copies of inscriptions found at Ellora and written in Ashoka Brahmi, the still undeciphered pin-men. He had probably sent them to Wilford because Benares, the holy city of the Hindus, was the most likely place to find a Brahmin who might be able to read them. In 1793 Wilford announced that he had found just such a man:

"I have the honour to return to you the facsimile of several inscriptions with an explanation of them. I despaired at first of ever being able to decipher them... However, after many fruitless attempts on our part, we were so fortunate as to find at last an ancient sage, who gave us the key, and produced a book in Sanskrit, containing a great many ancient alphabets formerly in use in different parts of India. This was really a fortunate discovery, which hereafter may be of great service to us."

According to the ancient sage, most of Wilford's inscriptions related to the wanderings of the five heroic Pandava brothers from the Mahabharata. At the unspecified time in question they were under an obligation not to converse with the rest of mankind; so their friends devised a method of communicating with them by "writing short and obscure sentences on rocks and stones in the wilderness and in characters previously agreed upon betwixt them." The sage happened to have the key to these characters in his code book; obligingly he transcribed them into Devanagari Sanskrit and then translated them.

To be fair to Wilford, he was a bit suspicious about this ingenious explanation of how the inscriptions got there. But he had no doubts that the deciphering and translation were genuine. "Our having been able to decipher them is a great point in my opinion, as it may hereafter lead to further discoveries, that may ultimately crown our labours with success." Above all, he had now located the code book, "a most fortunate circumstance."

Poor Wilford was the laughing stock of the Benares Brahmins for a whole decade. They had already fobbed him off with Sanskrit texts, later proved spurious, on the source of the Nile and the origin of Mecca. After the code book there was a geographical treatise on The Sacred Isles of the West, which included early Hindu reference to the British Isles. The Brahmins, to whom Sanskrit had so long remained a sacred prerogative, were getting their own back. One wonders how much Wilford paid his "ancient sage."

Jones was already a little suspicious of Wilford's sources, but on the code book, which was as much a fabrication as the translations supposedly based on it, he reserved judgment until he might see it. He never did. In fact it was never heard of again. But in spite of these disappointments Jones continued to believe that in time this oldest script would be deciphered. He had been sent a copy of the writings on the Delhi pillar and told a correspondent that they "drive me to despair; you are right, I doubt not, in thinking them foreign; I believe them to be Ethiopian and to have been imported a thousand years before Christ." It was not one of his more inspired guesses and at the time of his death the mystery of the inscriptions and of the monoliths was as dark as ever.

-- India Discovered, by John Keay

It must, however, be recognized that in the last of his memoirs, which is also the least imperfect (I am not speaking of the posthumous publication, in nos. 220 and 223, 1851; of the Journal of the Society of Calcutta, of a essay in comparative geography which is a work of the worst times of Wilford), it must be recognized, I say, that, in the last of his memoirs, inserted in volume XIV of the Asiatic Researches (1822), and which has for its title On the ancient Geography of India, there are here and there useful indications which have been furnished him principally by treatises on Sanskrit geography of a very modern date, in truth, but which contain none the less, on indigenous nomenclature, more detailed notions than those of European investigators....

It would also be useful to obtain some of the modern treatises on geography which exist, it is said, in several countries of India, notably among the Djaïnas of Malvah and Gudjérat; we know that Wilford had several works of this kind in his hands, and that he especially made great use, for his last works, of the Samâsa-Kchetra (Collection of Countries), a prescriptive [relating to the imposition or enforcement of a rule or method.] treatise on geography written in the seventeenth century. However modern these works may be, and however mixed they may be with fables and errors, one should find in them good indications, from which European criticism will be able to turn to good account. Wilford also speaks of two ancient treatises on Sanskrit geography, one of the fifth-sixth century of our era, the other of the tenth-sixth century; the discovery of one or the other of these works would surely be a very useful acquisition.

-- Etuden Sur La Geographie Et Les Populations Primitives Du Nord-Ouest De L'Inde D'Apres Les Hymnes Vediques Precedee D'Un Apercu De L'Etat Actuel Des Etudes Sur L'Inde Ancienne, by Par M. Vivien De Saint-Martin, 1855 (Study on the Geography and the Primitive Populations of North-West India According to the Vedic Hymns Preceded by an Overview of the Current State of Studies on Ancient India, by M. Vivien De Saint-Martin, 1855)

The fifth is the Vicrama-sagara: the author of it is unknown here: however it is often mentioned in the Cshetra-samasa, which, according to the author himself, is chiefly taken from the Vicrama-sagara. It is said to exist still in the peninsula, and it existed in Bengal, in the year 1648. It is considered as a very valuable work, and Palibothra is particularly mentioned in it, according to the author of the Cshetra-samasa. I have only seventeen leaves of this work, and they are certainly interesting. Some suppose that it is as old as the time of Bucca-raya, that it was written by his order, and that the author was a native of the Dekhin.

But the author could not be a native of that country, otherwise, he would have given a better description of it; for his account of the country about the Sahyadri mountains, of which an extract is to be found in the Cshetra-samasa, is quite unsatisfactory, and obviously erroneous even in the general outlines. The account he gives of Trichina-vali is much better, and their he takes notice of an ancient city, which proves to be the Bata of Ptolemy, the metropolis of the Bata. Its Sanscrit name is Vata or Bata, so called because it was situated in the Bataranya, or forest of the Vat tree or Ficus Indica. Our author says that it is two Cos from Cuttalam, called Curtalam in Major Rennell’s map of India, and to the west of Tranquebar: it was a famous place formerly; but it is hardly known in the Caliyug, says our author. Close to it is Trimbalingali-grama. Two Cos to the west of Vataranya, is Madhyarjuna, a considerable place, and five Cos from this is Cumbhacolam, a large place also, inhabited chiefly by pot-makers; hence its name, and it is the Combaconum of the maps. The distance between Cuttalam and Cumbhacolam is nine Cos, and according to Major Rennell’s maps, it is about sixteen B. miles, which is sufficiently accurate.

The sixth is called the Bhuvana-cosa, and is declared to be a section of the Bhavishya-purana. If so, it has been revised, and many additions have been made to it, and very properly, for in its original state, it was a most contemptible performance. As the author mentions the emperor Selim-Shah, who died in the year 1552, he is of course posterior to him. It is a valuable work. Additions are always incorporated into the context in India, most generally without reference to any authority; and it was formerly so with us; but this is no disparagement in a geographical treatise: for towns, and countries do not disappear, like historical facts, without leaving some vestiges behind. I have only the fourth part of it, which contains the Gangetick provinces. The first copy that I saw, contained only the half of what is now in my possession; but it is exactly the same with it, only that some Pandit, a native of Benares, has introduced a very inaccurate account of the rebellion of Chaityan-Sinha, commonly called Cheyt-Sing, in the year, I believe 1781: but the style is different.

The seventh is the Cshetra-samasa already mentioned, and which was written by order of Bijjala, the last Raja of Patna, who died in the year 1648. Though a modern work, yet it is nevertheless a valuable and interesting performance. It contains only the Gangetick provinces and some parts of the peninsula, such as Trichina-vali, &c. The death of the Raja prevented his Pandit Jagganmohun from finishing it, as it was intended, for the information of his children.

The last chapter, which was originally a detached work, is an account of Patali-putra, and of Pali-bhata as it is called there, and it consists of forty-seven leaves. This was written previously to the geographical treatise, and it gives an account, geographical, historical, and also mythological of these two cities, which were contiguous to each other. It gives also a short history of the Raja's family, and of his ancestors, and on that account only was this small tract originally undertaken. We may of course reasonably suppose that it was written at least 170 years ago.

What Does Megasthenes Say About The Kings Who Ruled?

1. He calls Sandracottus the king of the Prassi and he mentions the names of Xandramus as predecessor and Sandrocyptus as successor to Sandracottus. There is absolutely no resemblance in these names to Bindusara (the successor to Chandragupta Maurya) and Mahapadma Nanda, the predecessor.

2. He makes absolutely no mention of Chanakya or Vishnugupta, the Acharya who helped Chandragupta ascend the throne.

3. He makes no mention of the widespread presence of the Baudhik or Sramana tradition [Rishi tradition] during the time of the Maurya empire.

4. He claims the capital is Palimbothra or Palibothra, and that the city exists near the confluence of the Ganga and the Eranaboas (Hiranyabahu). But the Puranas are clear that all the 8 dynasties after the Mahabharata war had their capital at Girivraja (Rajagriha), located in the foothills of the Himalayas. There is no mention of Pataliputra in the Puranas. So, the assumption made by Sir William that Palimbothra is Pataliputra has no basis in fact and is not attested by any piece of evidence. If the Greeks could pronounce the first P in (Patali) they could certainly have pronounced the second p in Putra, instead of bastardising it as Palimbothra. Granted the Greeks were incapable of pronouncing any Indian names, but there is no reason why they should not be consistent in their phonetics.

5. The empire of Chandragupta was known as Magadha Empire. It had a long history even at the time of Chandragupta Maurya. In Indian literature, this powerful empire is amply described by its name but the same is absent in Greek accounts. It is difficult to understand as to why Megasthenes did not use this name “Magadha” and instead used the word Prassi, which has no equivalent or counterpart in Indian accounts.

-- Historical Dates From Puranic Sources, by Prof. Narayan Rao

The writer informs us that, long after the death of Raja Bijjala or Baijjala, he was earnestly requested by his friends, to complete the work, or at least to arrange the materials he had already collected in some order, and to publish it, even in that state. He complied with their request; but it must have been long after the death of the king, for he mentions Pondichery; saying, that it was inhabited by Firangs, and had three pretty temples dedicated to the God of the Firanga, Feringies or French, who did not, I believe, settle there before the year 1674. He takes notice also of Mandarajya, or Madras.

The author acts with the utmost candour, and modesty, saying, as I have written the Prabhoda-chandrica after the "Pracriya-caumudi (that is to say from, and after the manner of that book) so I have written this work after the Vicrama-sagara, and also from enquiries, from respectable well informed people, and from what, I may have seen myself."

In the Cshetra-samasa, two other geographical tracts are mentioned; the first is the Dacsha-chandaca, and the other is called Desa-vali, which, according to the author’s account, seem to be valuable works. There is also a small geographical treatise called Crita-dhara-vali, by Rameswara, about 200 years old, it is supposed. I have only eighty leaves of it, and it contains some very interesting particulars. In the peninsula, there is a list of fifty-six countries, in high estimation among the natives. It is generally called, in the spoken dialects of India, Chhapana-desa or the fifty-six countries. It was mentioned first by Mr. Bailly, who calls it Chapanna de Chalou. Two copies were possessed by Dr. Buchanan, and I have also procured a few others. All these are most contemptible lists of names, badly spelt, without any explanation whatever, and they differ materially the one from the other. However there is really a valuable copy of it, in the Tara-tantra, and published lately by the Rev. Mr. Ward [William Ward, b. 1769 Derby][???]. I have also another list of countries with proper remarks, from the Galava-tantra[???], in which there are several most valuable hints. However these two lists must be used cautiously, for there are also several mistakes.

SECTION XXX.

Tara* [The Deliverer.]

THIS is the image of a black woman, with four arms, standing on the breast of Shivu: in one hand she holds a sword, in another a giant's head, with the others she is bestowing a blessing, and forbidding fear.

The worship of Tara is performed in the night, in different months, at the total wane of the moon, before the image of Siddheshwuree, when bloody sacrifices are offered, and it is reported, that even human beings were formerly immolated in secret to this ferocious deity, who is considered by the Hindoos as soon incensed, and not unfrequently inflicting on an importunate worshipper the most shocking diseases, as a vomiting of blood, or some other dreadful complaint which soon puts an end to his life.

Almost all the disciples of this goddess are from among the heterodox; many of them, however, are learned men, Tara being considered as the patroness of learnings. Some Hindoos are supposed to have made great advances in knowledge through the favour of this goddess; and many a stupid boy, after reading some incantations containing the name of Tara, has become a learned man....

About seven years ago, at the village of Serampore, near Kutwa, before the temple of the goddess Tara, a human body was found without a head, and in the inside of the temple different offerings, as ornaments, food, flowers, spirituous liquors, &c. All who saw it know, that a human victim had been slaughtered in the night, and search was made after the murderers, but in vain.

-- A View of the History, Literature, and Religion of The Hindoos: Including a Minute Description of Their Manners and Customs, and Translations from Their Principal Works, by the Rev. W. Ward, One of the Baptist Missionaries at Serampore, Second Edition, Carefully Abridged, and Greatly Improved, Serampore, 1815

P. 380.

This essay on the ancient geography of the Gangetick provinces, will consist of three sections. The first will treat of the boundaries, mountains, and rivers. In the second will be described the various districts, with some account of them, as far as procurable. The third section will be a comparative essay, between the geographical accounts of these countries by Ptolemy, and other ancient geographers in the west, with those of the Pauranics. Then occasionally, and collaterally will appear accounts, both historical and geographical of some of the principal towns, such as Palibothra and Patali-putra now Patna, for these two towns were close to each other, exactly like London and Westminister.

The former was once the metropolis of India; but at a very early period it was destroyed by the Ganges: an account of it is in great forwardness, and is nearly ready for the press. Its name in Sanscrit was Pali-bhatta, to be pronounced Pali-bhothra, or nearly so. Bali-gram near Bhagalpur, never was the metropolis of India; yet it was a very ancient city, and its history is very interesting. It was also destroyed by the Ganges. Chattrapur or Chattra-gram, was the metropolis of a district in Bengal called Ganga-Riddha. It is now Chitpur, near Calcutta, and it was the Ganga or Gange-Regia of Ptolemy. Dhacca, or rather Firingi-Bazar, is the Tugma of Ptolemy, the Taukhe of Ei-Edrissi, and the Antomela of Pliny, &c.

Accurate copies of these Sanscrit treatises on geography, will be deposited with the Asiatick Society, and ultimately the originals themselves.

SECTION I. Boundaries of Anu-Gangam. Its Forests, Mountains and Rivers.

ANU-GANGAM signifies that country which extends along the banks of the Ganges. The Gangetick provinces are called to this day Anonkhenk, or Anonkhek in Tibet, and Enacac, by the Tartars; and they have extended this appellation even to all India. The Ganges is called Kankh, or Kankhis in Tibet, and Kengkia, or Hengho by the Chinese.* [See Alph. Tibet, p. 344, and Des Guignes, &c. &c.]

Anu-Gangam has to the north the Himalaya mountains and to the south those of Vindhya, with the bay of Bengal: the southern boundary of Aracan is also the limit of Anu-gangam towards the south in that part of the country. To the west it has the river Drishadvati, now the Caggar.

Of the eastern boundary, we can at present ascertain only a few points, which however will give us the grand outlines. The Raghu-nandana mountains to the east of Aracan, and of Chatta-gram, are the boundary in the south-east: from thence it trends towards the N.E. to a place called Mairam, eight Yojanas or sixty miles to the east of Manipur, which last is upon a river called Brahmo-tarir. Mairam's true Sanscrit name is Maya-rama, and is amongst hills on the river Subhadra, which goes into the country of Barama according to the Cshetra-samasa. The Subhadra is the Kayndwayn mentioned in the account of the embassy to Ava, and it falls into the Airavati in the Burman empire. From Mairan, the boundary goes to a place called Manatara, near the mountains of Prabhucuthara, which join the snowy mountains in some place unknown. The Prabhu mountains are the eastern boundary of Asam, and through them is a tremendous chasm made by Parasu-rama, and which gives entrance to the Brahma-putra into India.

Beyond these are the famous Udaya, or Unnati mountains or range, beyond which the sun rises.

The Vindhyan hills extend from the bay of Bengal to the gulf of Cambay, and they are divided into three parts. The first or eastern part extends from the bay of Bengal to the source of the Narmada and Sona rivers inclusively, and this part contains the Ricsha, or bear mountains. To the west of this, as far as the gulf of Cambay, is the second or western part, the southern part of which is called Pariyatra, or Paripatra, and the northern part, which extends from the gates of Dilli to the gulf of Cambay is called Raivata.

Now the third or southern portion of these hills is simply called Vindhya, and is to the south of the source of the rivers Narmada and Sona: the rivers Tapi or Tapti, and the Vaitarani near Cuttac, rise from the hills of Vindhya, simply so called. All the Puranas agree in their description of the hills and rivers of India, except that the Raivat hills are always omitted in this account: but they make a conspicuous figure in the history of Crishna.

The inferior mountains in this extensive region are first, the Rajamehal hills, called in Sanscrit Sishuni: they are well described in the commentary on the Maha-bharat: they are also called Cacshivat, from a tribe of Brahmens of that name, settled there, and well known to the Puranas.

Then come the Chadgadri, or the rhinoceros hill, from Chadga, to be pronounced Charga, or nearly so, the Sanscrit name of that animal; and which still remains in the names of the two districts of Carruckpur, and Carrucdea. They are mentioned in the Cshetra-samasa. Elian observes, that in India, they gave the name of Carcason, to an animal with a single horn. This word comes from Charga, and in the possessive case, and in a derivative form Chargasya. In Persian, this word is pronounced Kharrack and Khark.

To the S.W. of these, according to the Galava-tantra[???], is the Gridhracuta, or the vulture peak; the hills called Ghiddore in the maps.

Between these and the Sona are the famous hills of Raja-griha, because there was the royal mansion of Jarasandha. They are called also Giri-vraja, because he had there numberless cow-pens. Between the Sona and the Ganges at Benares and Chunar are the Maui hills, called also Rohita, or the red hills, and after them the fort of Rohtas is denominated.

Between the Sona, and the Tamasa, or Tonsa, is the extensive range of Caimur, in Sanscrit Cimmrityu, so called because it is fortunate to die* [G. Commentary, p. 695 of my MS.] amongst them. The hills of Calanjara, and Chitra-cuta, or Chitra-sanu in Bandela-chand, are often mentioned in the Puranas, and also in some poetical works. Beyond the Chambala are the famous hills of Raivata, which stretch from the Yamuna, down to Gurjarat, and in a N.W. direction along the Yamuna, as far as Dilli. That part of them which lies to the west of Mathura, as far north as Dilli, is called the Deva-giri hills, in the Scanda-purana, and Maya-giri, in the Bhagavat.† [Scanda-purana, section of Reva. Bhagavat, section the 10th.] They were the abode of the famous Maya, the chief engineer of the Daityas. He makes a most conspicuous figure in the Puranas, and particularly in the Maha-bharata. The scene of his many achievements, and performances was about Dilli. The inhabitants of these hills calls themselves Mayas or Meyos, to this day: but by their neighbours they are denominated Meyovati, or Mevatis.

The inferior mountains in the east, are the Gara hills, in the spoken dialects Garo, between the Brahma-putra and Silhet, along the southern boundary of Asama. They form a very extensive range, the western parts of which are called Doranga-giri or Deran-giri, from the country they are in; in the eastern parts they are denominated Numrupai from the country likewise.* [Namrupa is different from Camrupa, which is toward the N.W. in Asama, and the former toward the S.E. Camrupa is to the north of the Brahma-putra, and Namrupa to the south of it.] To the south of Gada or Garganh, are the Sarada hills, mentioned in the Calici-purana[???]: the natives call them Saraida, and there are the tombs of the kings of Asama.

The Kalika Purana, also called the Kali Purana, Sati Purana or Kalika Tantra, is one of the eighteen minor Puranas (Upapurana) in the Shaktism tradition of Hinduism. The text ... is attributed to the sage Markandeya [an ancient rishi born in the clan of Bhrigu Rishi [mentioned in] the Bhagavata Purana ...[and] the Mahabharata]. It exists in many versions, variously organized in 90 to 93 chapters. The surviving versions of the text are unusual in that they start abruptly and follow a format not found in either the major or minor Purana-genre mythical texts of Hinduism....

According to Rocher, the mention of king Dharmapala of Kamarupa has led to proposals of Kalika Purana being an 11th or 12th-century text...

The earliest printed edition of this text was published by the Venkateshvara Press, Bombay in 1907.

-- Kalika Purana, by Wikipedia

The Kalki Purana is a Vaishnavism-tradition Hindu text about the tenth avatar of Vishnu named Kalki. The Sanskrit text was likely composed in Bengal during an era when the region was being ruled by the Bengal Sultanate or the Mughal Empire. Wendy Doniger dates it to sometime between 1500 CE and 1700 CE. It has a floruit of 1726 CE based on a manuscript discovered in Dacca, Bangladesh.

-- Kalki Purana, by Wikipedia

There is another range of mountains to the east of Tiperah, and which forming a curve towards the N.E. passes a little to the eastward of the country of an ancient king called Hedamba, or Heramba. The name of the country is Casur, and its metropolis is Chaspur, the Cachara and Cuspoor of the maps. These hills are called Tiladri, or mountains of Tila, in the Cshetra-samasa. In them and to eastward of Casara is Tiladri-mala-gram, or the village of Mala, in the hills of Tila. It is called in the spoken dialects Tilandrira-mala, and the author of the above tract]???] says that it is a pretty place.

To the north of India are three ranges of mountains. Hima or snowy, is to the north of Nipala or Naya-pala; Hema or the golden mountain, is beyond Tibet, and Nishadha is still further north. Nay-pala is between the Padapa or foot of the mountains and Hima. Our ancient geographers were acquainted with the two first: Hima or Imaus; and Hema, Hemada, Hemoda, or Emodus. Their information was no doubt very defective, and their ideas concerning them were of course very indistinct and confused, as appears from Ptolemy’s map. That author has added an inferior range, which he calls Bepyrrhus. This range, with Imam and Emodus, he has disposed in the shape of the letter Y. Imaus is the shaft, and the others make the two branches; Emodus is to the left or north, and Bepyrrhns to the right or south. Emodus beyond Tibet is entirely out of its place here, and of course must be rejected. Bepyrrhus is derived from the Sanscrit Bhima-pada, or Bhaya-pada, or the tremendous pass up and down the mountains; literally the tremendous footings, rests for the foot, or steps. These words are pronounced by the Nay-palese Bhim-phed, or Bhim-pher, and Bhay-phed, or Bhay-pher: but in Hindee they say Bhim-paid, Bhay-pair and Bhim-pairi, Bhay-paid, or Bhay-pairi.

The Pauranics admit it is true, this etymological derivation of these words, and of Bhima-pur or Bhaya-pur, the dreary mansion: but they have transferred the sensation of terror from strangers and travellers to the inhabitants themselves, and have framed several legends accordingly. When Parasurama undertook to destroy the Cshettris, the Chasas, who then lived below in the plains, fled to the mountains, where they concealed themselves in the greatest dismay and consternation. A vast body of them went to Jalpesa, or the place of the lord of speech, at the foot of the hills, and a little to the eastward of the Tista, to consult him and claim his protection. They then ascended the tremendous Ghats, according to the Cshetra-samasa. In the same treatise, it is said, another body of them to the north of Asama ascended the hills and settled at a place called also Bhima-vati-puri, or the town replete with fear and terror, more commonly Bhim-puri and Bhim-pairi, which implies that the town pur, the valleys and passes, pair or paer, at the foot of these hills, were filled with alarm, and the inhabitants still tremble at the name of Parasu-rama. In the commentary on the Maha-bharat, the name of this place* [Page 538 of my MS.] is written Bhima-spharddha, or rather Bhima-sparddha, because Bhima, having defeated, in these passes, the army of Banasura, laughed and rejoined in consequence of his victory. The first etymology, I think, is by far preferable. This appears to be the mount Bepyrrhus of Ptolemy, and its erroneous direction in his map may be rectified: Bepyrrhus, and Ottorocorrha are parts of the Padapa, or foot of mount Himalaya, and ought to be connected as such, Bepyrrhus to the west, and Ottorocorrha to the east and to the north of Asama: for the latter is only a prolongation of the former.

The country of Gada, or Gada-grama, is pronounced by the natives Gorganh, or Guer-ganh, that is to say the town of Gor, whatever be its meaning, and through the rest of India it is called Gor, and also by our writers of the 17th century. Even Ptolemy writes it Corrha as in Ottoro-corrha. This country is generally called Asama, and is divided into two parts, Uttara or Uttara-gora, and Dacshina-gora, in the spoken dialects Uttar-gol and Dekhin-gol, that is to say, north and south Gora. In the spoken dialects these two divisions are also called Uttar-pada and Dekhin-pada, that is to say the N. and S. division.

The Damasi of Ptolemy imply the southern mountains, from the Sanscrit Yamya, and Yamasya, which signify the south; because Yama rules there. These words, in the spoken dialects, are pronounced Jamya, and Jamasya, from which last the Greeks made Damasoi, as Diamuna for Jamuna; and when Pliny says, that the Hindus called the southern parts of the world Dramasa, we should read Diamasa or Damasa. Besides Jama, or Pluto, is supposed to reside particularly there also, hence these mountains or part of them are called Jama-dhara, which imply either the southern mountains, or the mountains of Jama, the ruler of the south, in Sanscrit. In the spoken dialects, they say Jamdhera, from which Bernier made Chamdara.* [Account of Asama, Asiatick Researches, Vol. 2d p. 175.]

Beyond Asama are the Prabhu-cuthara mountains, beyond which are those called Udaya, or from behind which the sun makes his appearance.

Immediately after the mountains of Asama, according to Ptolemy are those called Semanthini, which appear to be the Udaya mountains of the Pauranics, and the Unnati of lexicons. These are declared to be the Samanta, or the very limit of the world, from which Ptolemy made Semanthini. We may also say Samunnati the very place of the rising of the sun; for the particle Sam is used here intensively. Samanta is found in lexicons; the other never to the best of my knowledge; still it is admissible, for it is correct and grammatical.

Let us pass to the mountains to the east of Bengal. Between that country, and Traipura, there is a range of hills, which passes close to Comillah, then all along the sea shore, and ends near Chatganh. This range is called Raghu-nandana in the Cshetra-samasa, and in the district of Chatganh there are two portions of it, one is called Chandra-sechara or Chandra-giri; in this is Sita-cunda, or the pool of Sita, and the burning well. The other portion is called Virupacshya.

The mountains to the eastward of Traipura, and of Chatganh, are mentioned in the above geographical treatise: in the northern parts they are called the Tiladri or Tailadri mountains, with several places of that name as we have seen before. The Peguers are called also Tatians, and it is possible that the Tailadri or the mountain of Tila or Taila may have been so called from that circumstance: for they constitute, at least in the lower parts of that range, the natural boundary between Indi, and the Talian country, or Pegu. Between Aracan and Ava is the famous pass of Talla or Tallaki.