Vedanta

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/7/21

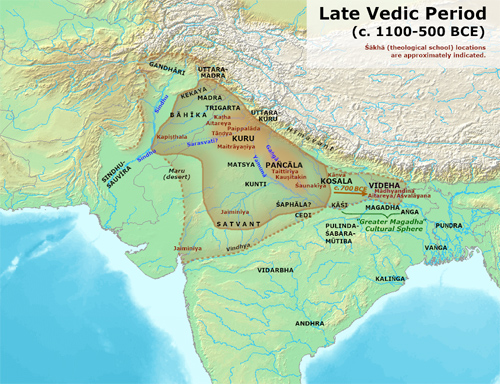

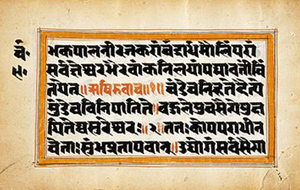

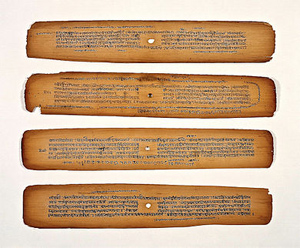

I have a larger vision or fantasy of original Indian Buddhism as an ocean with many icebergs, each representing the local textual traditions...of the different parts of the Indian world. Those icebergs are mostly gone...We have the Pali canon...the partial Sanskrit canon...They had a common core but they had many different texts in and around that basic commonality... and... there's no hope of finding them mainly for a simple physical reason, the climate of...India proper is such that organic materials...never last for more than a few hundred years. There are really no really old manuscripts in India proper. You only get the ancient manuscripts from the borderlands of India, in this case Gandhara which has a more moderate climate.

-- One Buddha, 15 Buddhas, 1,000 Buddhas, by Richard Salomon

Max Muller had expected great things from Schelling, and in a letter to his mother thus describes his first visit to the great philosopher: —

Translation.'I went to announce myself. He receives people at four o'clock. I had not expected much, for I had heard how he had dismissed Jellinick, but I was more fortunate. I asked him if he would continue to lecture next term on the Philosophy of Revelation, He said he could not decide yet, therefore probably only a private lecture again. Then I spoke to him of my time in Leipzig, of Weiss and Brockhaus, and then we came round to Indian Philosophy. Here he allowed me to tell him a good deal. I especially dwelt on the likeness between Sankhya and his own system, and remarked how an inclination to the Vedanta showed itself. He asked what we must understand by Vedanta, how the existence of God was proved, how God created the world, whether it had reality. He has been much occupied with Colebrooke's Essays, and he seemed to wish to learn more, as he asked me if I could explain a text. Then he asked where I was living, knew my father as Greek poet and a worker on Homer, and at last dismissed me with "Come again soon," offering to do anything he could for me.'

-- The Life and Letters of The Right Honourable Friedrich Max Muller, Edited by His Wife [Georgina Adelaide Grenfell Muller]

Fragm. LIV.

Pseudo-Origen, Philosoph, 24, ed. Delarue, Paris, 1733, vol. I. p. 904.

Of the Brahmans and their Philosophy.

(Cf. Fragm. xli., xliv., xlv.)

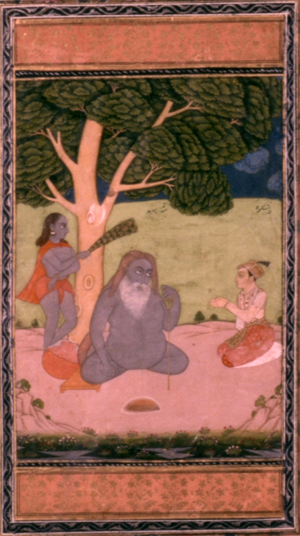

Of the Brachhmans in India.

There is among the Brachhmans in India a sect of philosophers who adopt an independent life, and abstain from animal food and all victuals cooked by fire, being content to subsist upon fruits, which they do not so much as gather from the trees, but pick up when they have dropped to the ground, and their drink is the water of the river Tagabena. [Probably the Sanskrit Tungavena, now the Tungabhadra, a large affluent of the Krishna.] Throughout life they go about naked, saying that the body has been given by the Deity as a covering for the soul. [Vide Ind. Ant. vol. V. p. 128, note. A doctrine of the Vedanta school of philosophy, according to which the soul is incased as in a sheath, or rather a succession of sheaths. The first or inner case is the intellectual one, composed of the sheer and simple elements uncombined, and consisting of the intellect joined with the live senses. The second is the mental sheath, in which mind is joined with the preceding, or, as some hold, with the organs of action. The third comprises these organs and the vital faculties, and is called the organic or vital case. These three sheaths (kosa) constitute the subtle frame which attends the soul in its transmigrations. The exterior case is composed of the coarse elements combined in certain proportions, and is called the gross body. See Colebrooke's Essay on the Philosophy of the Hindus, Cowell's ed. pp. 395-6.]

They hold that God is light, [The affinity between God and light is the burden of the Gayatri or holiest verse of the Veda.] but not such light as we see with the eye, nor such as the sun or fire, but God is with them the Word, — by which term they do not mean articulate speech, but the discourse of reason, whereby the hidden mysteries of knowledge are discerned by the wise. This light, however, which they call the Word, and think to be God, is, they say, known only by the Brachhmans themselves, because they alone have discarded vanity, which is the outermost covering of the soul. [[x], which probably translates ahankara, literally 'egotism,' and hence 'self-consciousness,' the peculiar and appropriate function of which is selfish conviction; that is, a belief that in perception and meditation 'I' am concerned; that the objects of sense concern Me — in short, that I AM. The knowledge, however, which comes from comprehending that Being which has self-existence completely destroys the ignorance which says 'I am.']

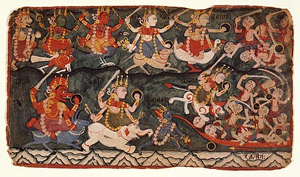

The members of this sect regard death with contemptuous indifference, and, as we have seen already, they always pronounce the name of the Deity with a tone of peculiar reverence, and adore him with hymns. They neither have wives nor beget children. Persons who desire to lead a life like theirs cross over from the other side of the river, and remain with them for good, never returning to their own country. These also are called Brachhmans, although they do not follow the same mode of life, for there are women in the country, from whom the native inhabitants are sprung, and of these women they beget offspring. With regard to the Word, which they call God, they hold that it is corporeal, and that it wears the body as its external covering, just as one wears the woollen surcoat, and that when it divests itself of the body with which it is enwrapped it becomes manifest to the eye. There is war, the Brachhmans hold, in the body wherewith they are clothed, and they regard the body as being the fruitful source of wars, and, as we have already shown, fight against it like soldiers in battle contending against the enemy. They maintain, moreover, that all men are held in bondage, like prisoners of war, [Compare Plato, Phaedo, cap. 32, where Sokrates speaks of the soul as at present confined in the body as in a species of prison. This was a doctrine of the Pythagoreans, whose philosophy, even in its most striking peculiarities, bears such a close resemblance to the Indian as greatly to favour the supposition that it was directly borrowed from it. There was even a tradition that Pythagoras had visited India.] to their own innate enemies, the sensual appetites, gluttony, anger, joy, grief, longing desire, and such like, while it is only the man who has triumphed over these enemies who goes to God. Dandamis accordingly, to whom Alexander the Makedonian paid a visit, is spoken of by the Brachhmans as a god because he conquered in the warfare against the body, and on the other hand they condemn Kalanos as one who had impiously apostatized from their philosophy. The Brachhmans, therefore, when they have shuffled off the body, see the pure sunlight as fish see it when they spring up out of the water into the air.

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A.

Highlights:

Literally meaning "end of the Vedas", Vedanta reflects ideas that emerged from, or were aligned with, the speculations and philosophies contained in the Upanishads...

The main traditions of Vedanta...except Advaita Vedanta and Neo-Vedanta, are related to Vaishavism [Vishnu as the Supreme Lord.] and emphasize devotion, regarding Vishnu or Krishna or a related manifestation, to be the highest Reality. While Advaita Vedanta attracted considerable attention in the West due to the influence of Hindu modernists like Swami Vivekananda, most of the other Vedanta traditions are seen as discourses articulating a form of Vaishnav theology....

The word Vedanta literally means the end of the Vedas and originally referred to the Upanishads. Vedanta is concerned with the jñānakāṇḍa or knowledge section of the vedas which is called the Upanishads...

The Upanishads may be regarded as the end of Vedas in different senses:

1. These were the last literary products of the Vedic period.

2. These mark the culmination of Vedic thought.

3. These were taught and debated last, in the Brahmacharya (student) stage...

Despite their differences, all schools of Vedanta share some common features...

• The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras constitute the basis of Vedanta...

• Rejection of Buddhism and Jainism and conclusions of the other Vedic schools (Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, and, to some extent, the Purva Mimamsa.)...

The Brahma Sutras attempted to synthesize the teachings of the Upanishads...

Shankara, in formulating Advaita, talks of two conceptions of Brahman: The higher Brahman as undifferentiated Being, and a lower Brahman endowed with qualities as the creator of the universe...

The Upanishads present an associative philosophical inquiry in the form of identifying various doctrines and then presenting arguments for or against them...

The notion of "inconceivability" (acintyatva) is used to reconcile apparently contradictory notions in Upanishadic teachings...He is all-pervading and thus in all parts of the universe (non-difference), yet he is inconceivably more (difference)...

Little is known of schools of Vedanta existing before the composition of the Brahma Sutras (400–450 CE)...

Though attributed to Badarayana, the Brahma Sutras were likely composed by multiple authors over the course of hundreds of years. The estimates on when the Brahma Sutras were complete vary...

[T]he cryptic nature of aphorisms of the Brahma Sutras have required exegetical commentaries.[109] These commentaries have resulted in the formation of numerous Vedanta schools, each interpreting the texts in its own way and producing its own commentary...

Little with specificity is known of the period between the Brahma Sutras (5th century CE) and Adi Shankara (8th century CE). Only two writings of this period have survived...

Early Vaishnava Vedanta retains the tradition of bhedabheda, equating Brahman with Vishnu or Krishna...

Dvaita Vedanta was propounded by Madhvacharya (1238–1317 CE). He presented the opposite interpretation of Shankara in his Dvaita, or dualistic system. In contrast to Shankara's non-dualism and Ramanuja's qualified non-dualism, he championed unqualified dualism...

Neo-Vedanta, variously called as "Hindu modernism", "neo-Hinduism", and "neo-Advaita", is a term that denotes some novel interpretations of Hinduism that developed in the 19th century, presumably as a reaction to the colonial British rule. King (2002, pp. 129–135) writes that these notions accorded the Hindu nationalists an opportunity to attempt the construction of a nationalist ideology to help unite the Hindus to fight colonial oppression. Western orientalists, in their search for its "essence", attempted to formulate a notion of "Hinduism" based on a single interpretation of Vedanta as a unified body of religious praxis. This was contra-factual as, historically, Hinduism and Vedanta had always accepted a diversity of traditions...

The neo-Vedantins argued that the six orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy were perspectives on a single truth, all valid and complementary to each other. Halbfass (2007, p. 307) sees these interpretations as incorporating western ideas into traditional systems, especially Advaita Vedanta. It is the modern form of Advaita Vedanta, states King (1999, p. 135), the neo-Vedantists subsumed the Buddhist philosophies as part of the Vedanta tradition and then argued that all the world religions are same "non-dualistic position as the philosophia perennis", ignoring the differences within and outside of Hinduism...

Ramakrishna, Vivekananda and Aurobindo have been labeled neo-Vedantists (the latter called it realistic Advaita), a view of Vedanta that rejects the Advaitins' idea that the world is illusory. As Aurobindo phrased it, philosophers need to move from 'universal illusionism' to 'universal realism', in the strict philosophical sense of assuming the world to be fully real.

A major proponent in the popularization of this Universalist and Perennialist interpretation of Advaita Vedanta was Vivekananda, who played a major role in the revival of Hinduism. He was also instrumental in the spread of Advaita Vedanta to the West ...

Matilal criticizes Neo-Hinduism as an oddity developed by West-inspired Western Indologists and attributes it to the flawed Western perception of Hinduism in modern India. In his scathing criticism of this school of reasoning, Matilal (2002, pp. 403–404) says:

The so-called 'traditional' outlook is in fact a construction...

The influence of Vedanta is prominent in the sacred literatures of Hinduism, such as the various Puranas, Samhitas, Agamas and Tantras...

Gavin Flood states, "... the most influential school of theology in India has been Vedanta, exerting enormous influence on all religious traditions and becoming the central ideology of the Hindu renaissance in the nineteenth century. It has become the philosophical paradigm of Hinduism 'par excellence'."...

While the Bhairava Shastras are monistic, Shiva Shastras are dualistic...

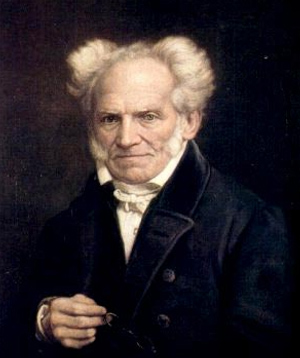

Arthur Schopenhauer, who called them the consolation of his life. He drew explicit parallels between his philosophy, as set out in The World as Will and Representation, and that of the Vedanta philosophy as described in the work of Sir William Jones...

German Sanskritist Theodore Goldstücker was among the early scholars to notice similarities between the religious conceptions of the Vedanta and those of the Dutch Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza, writing that Spinoza's thought was "... so exact a representation of the ideas of the Vedanta, that we might have suspected its founder to have borrowed the fundamental principles of his system from the Hindus, did his biography not satisfy us that he was wholly unacquainted with their doctrines"...

Max Müller noted the striking similarities between Vedanta and the system of Spinoza, saying, "The Brahman, as conceived in the Upanishads and defined by Sankara, is clearly the same as Spinoza's 'Substantia'."

Helena Blavatsky, a founder of the Theosophical Society, also compared Spinoza's religious thought to Vedanta, writing in an unfinished essay, "As to Spinoza's Deity...it is the Vedantic Deity pure and simple."

-- Vedanta, by Wikipedia

Vedanta (/vɪˈdɑːntə/; Sanskrit: वेदान्त, IAST: Vedānta; also Uttara Mīmāṃsā) is one of the six (āstika) schools of Hindu philosophy. Literally meaning "end of the Vedas", Vedanta reflects ideas that emerged from, or were aligned with, the speculations and philosophies contained in the Upanishads, specifically, knowledge and liberation. Vedanta contains many sub-traditions on basis of a common textual connection called the Prasthanatrayi: the Upanishads, the Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita.

All Vedanta schools, in their deliberations, concern themselves with, but differ in their views regarding, ontology, soteriology and epistemology.[1][2] The main traditions of Vedanta are:[3]

1. Bhedabheda (difference and non-difference), as early as the 7th century CE,[4] or even the 4th century CE.[5] Some scholars are inclined to consider it as a "tradition" rather than a school of Vedanta.[4]

o Dvaitādvaita or Svabhavikabhedabheda (dualistic non-dualism), founded by Nimbarka[6] in the 7th century CE[7][8]

o Achintya Bheda Abheda (inconceivable one-ness and difference), founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534 CE),[9] propagated by Gaudiya Vaishnava

2. Advaita (monistic), most prominent Gaudapada (~500 CE)[10] and Adi Shankaracharya (8th century CE)[11]

3. Vishishtadvaita (qualified monism), prominent scholars are Nathamuni, Yāmuna and Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE)

4. Dvaita (dualism), founded by Madhvacharya (1199–1278 CE)

5. Suddhadvaita (purely non-dual), founded by Vallabha[6] (1479–1531 CE)

Modern developments in Vedanta include Neo-Vedanta,[12][13][14] and the growth of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya.[15] All of these schools, except Advaita Vedanta and Neo-Vedanta, are related to Vaishavism [Vishnu as the Supreme Lord.] and emphasize devotion, regarding Vishnu or Krishna or a related manifestation, to be the highest Reality.[16][17] While Advaita Vedanta attracted considerable attention in the West due to the influence of Hindu modernists like Swami Vivekananda, most of the other Vedanta traditions are seen as discourses articulating a form of Vaishnav theology.[18]

Etymology and nomenclature

The word Vedanta is made of two words :

• Veda (वेद) - refers to the four sacred vedic texts.

• Anta (अंत) - this word means "End".

The word Vedanta literally means the end of the Vedas and originally referred to the Upanishads.[19][20] Vedanta is concerned with the jñānakāṇḍa or knowledge section of the vedas which is called the Upanishads.[21][22] The denotation of Vedanta subsequently widened to include the various philosophical traditions based on to the Prasthanatrayi.[19][23]

The Upanishads may be regarded as the end of Vedas in different senses:[24]

1. These were the last literary products of the Vedic period.

2. These mark the culmination of Vedic thought.

3. These were taught and debated last, in the Brahmacharya (student) stage.[19][25]

Vedanta is one of the six orthodox (āstika) schools of Indian philosophy.[20] It is also called Uttara Mīmāṃsā, which means the 'latter enquiry' or 'higher enquiry'; and is often contrasted with Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, the 'former enquiry' or 'primary enquiry'. Pūrva Mīmāṃsā deals with the karmakāṇḍa or ritualistic section (the Samhita and Brahmanas) in the Vedas.[26][27][a]

Vedanta philosophy

Common features

Despite their differences, all schools of Vedanta share some common features:

• Vedanta is the pursuit of knowledge into the Brahman and the Ātman.[29]

• The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras constitute the basis of Vedanta, providing reliable sources of knowledge (Sruti Śabda in Pramana);[30]

• Brahman, c.q. Ishvara (God, Vishnu), exists as the unchanging material cause and instrumental cause of the world. The only exception here is that Dvaita Vedanta does not hold Brahman to be the material cause, but only the efficient cause.[31]

• The self (Ātman/Jiva) is the agent of its own acts (karma) and the recipient of the consequences of these actions.[32]

• Belief in rebirth and the desirability of release from the cycle of rebirths, (mokṣa).[32]

• Rejection of Buddhism and Jainism and conclusions of the other Vedic schools (Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, and, to some extent, the Purva Mimamsa.)[32]

Prasthanatrayi (the Three Sources)

The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras constitute the basis of Vedanta. All schools of Vedanta propound their philosophy by interpreting these texts, collectively called the Prasthanatrayi, literally, three sources.[21][33]

1. The Upanishads,[ b] or Śruti prasthāna; considered the Sruti, the "heard" (and repeated) foundation of Vedanta.

2. The Brahma Sutras, or Nyaya prasthana / Yukti prasthana; considered the reason-based foundation of Vedanta.

3. The Bhagavad Gita, or Smriti prasthāna; considered the Smriti (remembered tradition) foundation of Vedanta.

The Brahma Sutras attempted to synthesize the teachings of the Upanishads. The diversity in the teaching of the Upanishads necessitated the systematization of these teachings. This was likely done in many ways in ancient India, but the only surviving version of this synthesis is the Brahma Sutras of Badarayana.[21]

All major Vedantic teachers, including Shankara, Bhaskara, Ramanuja, Nimbarka, Vallabha, and Madhva have composed commentaries not only on the Upanishads and Brahma Sutras, but also on the Bhagavad Gita. The Bhagavad Gita, due to its syncretism of Samkhya, Yoga, and Upanishadic thought, has played a major role in Vedantic thought.[35]

Metaphysics

Vedanta philosophies discuss three fundamental metaphysical categories and the relations between the three.[21][36]

1. Brahman or Ishvara: the ultimate reality[37]

2. Ātman or Jivātman: the individual soul, self[38]

3. Prakriti/Jagat:[6] the empirical world, ever-changing physical universe, body and matter[39]

Brahman / Ishvara – Conceptions of the Supreme Reality

Shankara, in formulating Advaita, talks of two conceptions of Brahman: The higher Brahman as undifferentiated Being, and a lower Brahman endowed with qualities as the creator of the universe.[40]

• Parā or Higher Brahman: The undifferentiated, absolute, infinite, transcendental, supra-relational Brahman beyond all thought and speech is defined as parā Brahman, nirviśeṣa Brahman or nirguṇa Brahman and is the Absolute of metaphysics.

• Aparā or Lower Brahman: The Brahman with qualities defined as aparā Brahman or saguṇa Brahman. The saguṇa Brahman is endowed with attributes and represents the personal God of religion.

Ramanuja, in formulating Vishishtadvaita Vedanta, rejects nirguṇa – that the undifferentiated Absolute is inconceivable – and adopts a theistic interpretation of the Upanishads, accepts Brahman as Ishvara, the personal God who is the seat of all auspicious attributes, as the One reality. The God of Vishishtadvaita is accessible to the devotee, yet remains the Absolute, with differentiated attributes.[41]

Madhva, in expounding Dvaita philosophy, maintains that Vishnu is the supreme God, thus identifying the Brahman, or absolute reality, of the Upanishads with a personal god, as Ramanuja had done before him.[42][43] Nimbarka, in his dvaitadvata philosophy, accepted the Brahman both as nirguṇa and as saguṇa. Vallabha, in his shuddhadvaita philosophy, not only accepts the triple ontological essence of the Brahman, but also His manifestation as personal God (Ishvara), as matter and as individual souls.[44]

Relation between Brahman and Jiva / Atman

The schools of Vedanta differ in their conception of the relation they see between Ātman / Jivātman and Brahman / Ishvara:[45]

• According to Advaita Vedanta, Ātman is identical with Brahman and there is no difference.[46]

• According to Vishishtadvaita, Jīvātman is different from Ishvara, though eternally connected with Him as His mode.[47] The oneness of the Supreme Reality is understood in the sense of an organic unity (vishistaikya). Brahman / Ishvara alone, as organically related to all Jīvātman and the material universe is the one Ultimate Reality.[48]

• According to Dvaita, the Jīvātman is totally and always different from Brahman / Ishvara.[49]

• According to Shuddhadvaita (pure monism), the Jīvātman and Brahman are identical; both, along with the changing empirically-observed universe being Krishna.[50]

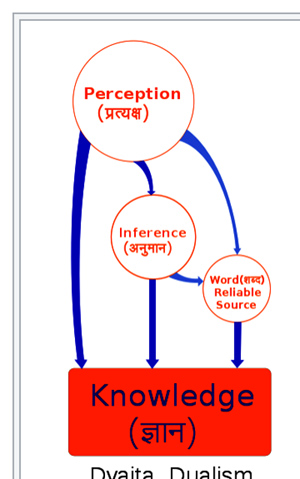

Epistemology in Dvaita and Vishishtadvaita Vedanta. Advaita and some other Vedanta schools recognize six epistemic means.

Epistemology

Main article: Pramana

Pramana

Pramāṇa (Sanskrit: प्रमाण) literally means "proof", "that which is the means of valid knowledge".[51] It refers to epistemology in Indian philosophies, and encompasses the study of reliable and valid means by which human beings gain accurate, true knowledge.[52] The focus of Pramana is the manner in which correct knowledge can be acquired, how one knows or does not know, and to what extent knowledge pertinent about someone or something can be acquired.[53] Ancient and medieval Indian texts identify six[c] pramanas as correct means of accurate knowledge and truths:[54]

1. Pratyakṣa (perception)

2. Anumāṇa (inference)

3. Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy)

4. Arthāpatti (postulation, derivation from circumstances)

5. Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof)

6. Śabda (scriptural testimony/ verbal testimony of past or present reliable experts).

The different schools of Vedanta have historically disagreed as to which of the six are epistemologically valid. For example, while Advaita Vedanta accepts all six pramanas,[55] Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita accept only three pramanas (perception, inference and testimony).[56]

Advaita considers Pratyakṣa (perception) as the most reliable source of knowledge, and Śabda, the scriptural evidence, is considered secondary except for matters related to Brahman, where it is the only evidence.[57][d] In Vishistadvaita and Dvaita, Śabda, the scriptural testimony, is considered the most authentic means of knowledge instead.[58]

Theories of cause and effect

All schools of Vedanta subscribe to the theory of Satkāryavāda,[4] which means that the effect is pre-existent in the cause. But there are two different views on the status of the "effect", that is, the world. Most schools of Vedanta, as well as Samkhya, support Parinamavada, the idea that the world is a real transformation (parinama) of Brahman.[59] According to Nicholson (2010, p. 27), "the Brahma Sutras espouse the realist Parinamavada position, which appears to have been the view most common among early Vedantins". In contrast to Badarayana, Adi Shankara and Advaita Vedantists hold a different view, Vivartavada, which says that the effect, the world, is merely an unreal (vivarta) transformation of its cause, Brahman.[e]

Overview of the main schools of Vedanta

Shankaracharya

The Upanishads present an associative philosophical inquiry in the form of identifying various doctrines and then presenting arguments for or against them. They form the basic texts and Vedanta interprets them through rigorous philosophical exegesis to defend the point of view of their specific sampradaya.[60][61] Varying interpretations of the Upanishads and their synthesis, the Brahma Sutras, led to the development of different schools of Vedanta over time.

According to Gavin Flood, while Advaita Vedanta is the "most famous" school of Vedanta, and "often, mistakenly, taken to be the only representative of Vedantic thought,"[1] and Shankara a Saivite,[62] "Vedanta is essentially a Vaisnava theological articulation,"[63] a discourse broadly within the parameters of Vaisnavism."[62] Within the Vaishnava traditions four sampradays have special status,[2] while different scholars have classified the Vedanta schools ranging from three to six[19][45][6][64][3][f] as prominent ones.[g]

1. Bhedabheda, as early as the 7th century CE,[4] or even the 4th century CE.[5] Some scholars are inclined to consider it as a "tradition" rather than a school of Vedanta.[4]

o Dvaitādvaita or Svabhavikabhedabheda (Vaishnava), founded by Nimbarka[6] in the 7th century CE[7][8]

o Achintya Bheda Abheda (Vaishnava), founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534 CE),[9] propagated by Gaudiya Vaishnava

2. Advaita (monistic), many scholars of which most prominent are Gaudapada (~500 CE)[10] and Adi Shankaracharya (8th century CE)[11]

3. Vishishtadvaita (Vaishnava), prominent scholars are Nathamuni, Yāmuna and Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE)

4. Dvaita (Vaishnava), founded by Madhvacharya (1199–1278 CE)

5. Suddhadvaita (Vaishnava), founded by Vallabha[6] (1479–1531 CE)

6. Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, based on the teachings of Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE) and propagated most nottably by BAPS[66][67][68][69]

Bhedabheda (difference and non-difference)

Main article: Bhedabheda

Bhedābheda means "difference and non-difference" and is more a tradition than a school of Vedanta. The schools of this tradition emphasize that the individual self (Jīvatman) is both different and not different from Brahman.[4] Notable figures in this school are Bhartriprapancha, Nimbārka (7th century)[7][8] who founded the Dvaitadvaita school, Bhāskara (8th–9th century), Ramanuja's teacher Yādavaprakāśa, Caitanya (1486–1534) who founded the Achintya Bheda Abheda school, and Vijñānabhikṣu (16th century).[70][h]

Dvaitādvaita

Nimbarkacharya's icon at Ukhra, West Bengal

Main article: Dvaitadvaita

Nimbārka (7th century)[7][8] sometimes identified with Bhāskara,[71] propounded Dvaitādvaita.[72] Brahman (God), souls (chit) and matter or the universe (achit) are considered as three equally real and co-eternal realities. Brahman is the controller (niyanta), the soul is the enjoyer (bhokta), and the material universe is the object enjoyed (bhogya). The Brahman is Krishna, the ultimate cause who is omniscient, omnipotent, all-pervading Being. He is the efficient cause of the universe because, as Lord of Karma and internal ruler of souls, He brings about creation so that the souls can reap the consequences of their karma. God is considered to be the material cause of the universe because creation was a manifestation of His powers of soul (chit) and matter (achit); creation is a transformation (parinama) of God's powers. He can be realized only through a constant effort to merge oneself with His nature through meditation and devotion. [72]

Achintya-Bheda-Abheda

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu

Main article: Achintya Bhedabheda

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486 – 1533) was the prime exponent of Achintya-Bheda-Abheda.[73] In Sanskrit achintya means 'inconceivable'.[74] Achintya-Bheda-Abheda represents the philosophy of "inconceivable difference in non-difference",[75] in relation to the non-dual reality of Brahman-Atman which it calls (Krishna), svayam bhagavan.[76] The notion of "inconceivability" (acintyatva) is used to reconcile apparently contradictory notions in Upanishadic teachings. This school asserts that Krishna is Bhagavan of the bhakti yogins, the Brahman of the jnana yogins, and has a divine potency that is inconceivable. He is all-pervading and thus in all parts of the universe (non-difference), yet he is inconceivably more (difference). This school is at the foundation of the Gaudiya Vaishnava religious tradition.[75]

Advaita Vedanta (non-dualism)

Main article: Advaita Vedanta

Advaita Vedanta (IAST Advaita Vedānta; Sanskrit: अद्वैत वेदान्त), propounded by Gaudapada (7th century) and Adi Shankara (8th century), espouses non-dualism and monism. Brahman is held to be the sole unchanging metaphysical reality and identical to the individual Atman.[43] The physical world, on the other hand, is always-changing empirical Maya.[77][ i] The absolute and infinite Atman-Brahman is realized by a process of negating everything relative, finite, empirical and changing.[78]

The school accepts no duality, no limited individual souls (Atman / Jivatman), and no separate unlimited cosmic soul. All souls and their existence across space and time are considered to be the same oneness. [79] Spiritual liberation in Advaita is the full comprehension and realization of oneness, that one's unchanging Atman (soul) is the same as the Atman in everyone else, as well as being identical to Brahman.[80]

Vishishtadvaita (qualified non-dualism)

Ramanujacharya depicted with Vaishnava Tilaka and Vishnu statue.

Main article: Vishishtadvaita

Vishishtadvaita, propounded by Ramanuja (11–12th century), asserts that Jivatman (human souls) and Brahman (as Vishnu) are different, a difference that is never transcended.[81][82] With this qualification, Ramanuja also affirmed monism by saying that there is unity of all souls and that the individual soul has the potential to realize identity with the Brahman.[83] Vishishtadvaita, like Advaita, is a non-dualistic school of Vedanta in a qualified way, and both begin by assuming that all souls can hope for and achieve the state of blissful liberation.[84] On the relation between the Brahman and the world of matter (Prakriti), Vishishtadvaita states both are two different absolutes, both metaphysically true and real, neither is false or illusive, and that saguna Brahman with attributes is also real.[85] Ramanuja states that God, like man, has both soul and body, and the world of matter is the glory of God's body.[86] The path to Brahman (Vishnu), according to Ramanuja, is devotion to godliness and constant remembrance of the beauty and love of the personal god (bhakti of saguna Brahman).[87]

Dvaita (dualism)

Madhvacharya

Main article: Dvaita

Dvaita, propounded by Madhvacharya (13th century), is based on the premise of dualism. Atman (soul) and Brahman (as Vishnu) are understood as two completely different entities.[88] Brahman is the creator of the universe, perfect in knowledge, perfect in knowing, perfect in its power, and distinct from souls, distinct from matter.[89] [j] In Dvaita Vedanta, an individual soul must feel attraction, love, attachment and complete devotional surrender to Vishnu for salvation, and it is only His grace that leads to redemption and salvation.[92] Madhva believed that some souls are eternally doomed and damned, a view not found in Advaita and Vishishtadvaita Vedanta.[93] While the Vishishtadvaita Vedanta asserted "qualitative monism and quantitative pluralism of souls", Madhva asserted both "qualitative and quantitative pluralism of souls".[94]

Shuddhādvaita (pure nondualism)

Vallabhacharya

Main articles: Shuddhadvaita and Pushtimarg

Shuddhadvaita (pure non-dualism), propounded by Vallabhacharya (1479–1531 CE), states that the entire universe is real and is subtly Brahman only in the form of Krishna.[50] Vallabhacharya agreed with Advaita Vedanta's ontology, but emphasized that prakriti (empirical world, body) is not separate from the Brahman, but just another manifestation of the latter.[50] Everything, everyone, everywhere – soul and body, living and non-living, jiva and matter – is the eternal Krishna.[95] The way to Krishna, in this school, is bhakti. Vallabha opposed renunciation of monistic sannyasa as ineffective and advocates the path of devotion (bhakti) rather than knowledge (jnana). The goal of bhakti is to turn away from ego, self-centered-ness and deception, and to turn towards the eternal Krishna in everything continually offering freedom from samsara.[50]

History

The history of Vedanta can be divided into two periods: one prior to the composition of the Brahma Sutras and the other encompassing the schools that developed after the Brahma Sutras were written.

Before the Brahma Sutras (before the 5th century)

Little is known[96] of schools of Vedanta existing before the composition of the Brahma Sutras (400–450 CE).[97][5][k] It is clear that Badarayana, the writer of Brahma Sutras, was not the first person to systematize the teachings of the Upanishads, as he quotes six Vedantic teachers before him – Ashmarathya, Badari, Audulomi, Kashakrtsna, Karsnajini and Atreya.[99][100] References to other early Vedanta teachers – Brahmadatta, Sundara, Pandaya, Tanka and Dravidacharya – are found in secondary literature of later periods.[101] The works of these ancient teachers have not survived, but based on the quotes attributed to them in later literature, Sharma postulates that Ashmarathya and Audulomi were Bhedabheda scholars, Kashakrtsna and Brahmadatta were Advaita scholars, while Tanka and Dravidacharya were either Advaita or Vishistadvaita scholars.[100]

Brahma Sutras (completed in the 5th century)

Main article: Brahma Sutras

Badarayana summarized and interpreted teachings of the Upanishads in the Brahma Sutras, also called the Vedanta Sutra,[102][l] possibly "written from a Bhedābheda Vedāntic viewpoint."[4] Badarayana summarized the teachings of the classical Upanishads[103][104][m] and refuted the rival philosophical schools in ancient India. Nicholson 2010, p. 26 The Brahma Sutras laid the basis for the development of Vedanta philosophy.[105]

Though attributed to Badarayana, the Brahma Sutras were likely composed by multiple authors over the course of hundreds of years.[5] The estimates on when the Brahma Sutras were complete vary,[106][107] with Nakamura in 1989 and Nicholson in his 2013 review stating, that they were most likely compiled in the present form around 400–450 CE.[97][n] Isaeva suggests they were complete and in current form by 200 CE,[108] while Nakamura states that "the great part of the Sutra must have been in existence much earlier than that."[107]

The book is composed of four chapters, each divided into four-quarters or sections.[21] These sutras attempt to synthesize the diverse teachings of the Upanishads. However, the cryptic nature of aphorisms of the Brahma Sutras have required exegetical commentaries.[109] These commentaries have resulted in the formation of numerous Vedanta schools, each interpreting the texts in its own way and producing its own commentary.[110]

Between the Brahma Sutras and Adi Shankara (5th–8th centuries)

See also: Vedas, Upanishads, and Darsanas

Little with specificity is known of the period between the Brahma Sutras (5th century CE) and Adi Shankara (8th century CE).[96][11] Only two writings of this period have survived: the Vākyapadīya, written by Bhartṛhari (second half 5th century,[111]) and the Kārikā written by Gaudapada (early 6th[11] or 7th century[96] CE).

Shankara mentions 99 different predecessors of his school in his commentaries.[112] A number of important early Vedanta thinkers have been listed in the Siddhitraya by Yamunācārya (c. 1050), the Vedārthasamgraha by Rāmānuja (c. 1050–1157), and the Yatīndramatadīpikā by Śrīnivāsa Dāsa.[96] At least fourteen thinkers are known to have existed between the composition of the Brahma Sutras and Shankara's lifetime.[o]

A noted scholar of this period was Bhartriprapancha. Bhartriprapancha maintained that the Brahman is one and there is unity, but that this unity has varieties. Scholars see Bhartriprapancha as an early philosopher in the line who teach the tenet of Bhedabheda.[21]

Gaudapada, Adi Shankara (Advaita Vedanta) (6th–9th centuries)

Main articles: Advaita Vedanta and Gaudapada

Influenced by Buddhism, Advaita vedanta departs from the bhedabheda-philosophy, instead postulating the identity of Atman with the Whole (Brahman),

Gaudapada

Gaudapada (c. 6th century CE),[113] was the teacher or a more distant predecessor of Govindapada,[114] the teacher of Adi Shankara. Shankara is widely considered as the apostle of Advaita Vedanta.[45] Gaudapada's treatise, the Kārikā – also known as the Māṇḍukya Kārikā or the Āgama Śāstra[115] – is the earliest surviving complete text on Advaita Vedanta.[p]

Gaudapada's Kārikā relied on the Mandukya, Brihadaranyaka and Chhandogya Upanishads.[119] In the Kārikā, Advaita (non-dualism) is established on rational grounds (upapatti) independent of scriptural revelation; its arguments are devoid of all religious, mystical or scholastic elements. Scholars are divided on a possible influence of Buddhism on Gaudapada's philosophy.[q] The fact that Shankara, in addition to the Brahma Sutras, the principal Upanishads and the Bhagvad Gita, wrote an independent commentary on the Kārikā proves its importance in Vedāntic literature.[120]

Adi Shankara

Adi Shankara (788–820), elaborated on Gaudapada's work and more ancient scholarship to write detailed commentaries on the Prasthanatrayi and the Kārikā. The Mandukya Upanishad and the Kārikā have been described by Shankara as containing "the epitome of the substance of the import of Vedanta".[120] It was Shankara who integrated Gaudapada work with the ancient Brahma Sutras, "and give it a locus classicus" alongside the realistic strain of the Brahma Sutras.[121][r] His interpretation, including works ascribed to him, has become the normative interpretation of Advaita Vedanta.[122][s]

A noted contemporary of Shankara was Maṇḍana Miśra, who regarded Mimamsa and Vedanta as forming a single system and advocated their combination known as Karma-jnana-samuchchaya-vada.[125][t] The treatise on the differences between the Vedanta school and the Mimamsa school was a contribution of Adi Shankara. Advaita Vedanta rejects rituals in favor of renunciation, for example.[126]

Early Vaishnavism Vedanta (7th–9th centuries)

Early Vaishnava Vedanta retains the tradition of bhedabheda, equating Brahman with Vishnu or Krishna.

Nimbārka and Dvaitādvaita

Main article: Dvaitadvaita

Nimbārka (7th century)[7][8] sometimes identified with Bhāskara,[71] propounded Dvaitādvaita Bhedābheda.[72]

Bhāskara and Upadhika

Bhāskara (8th–9th century) also taught Bhedabheda. In postulating Upadhika, he considers both identity and difference to be equally real. As the causal principle, Brahman is considered non-dual and formless pure being and intelligence.[127] The same Brahman, manifest as events, becomes the world of plurality. Jīva is Brahman limited by the mind. Matter and its limitations are considered real, not a manifestation of ignorance. Bhaskara advocated bhakti as dhyana (meditation) directed toward the transcendental Brahman. He refuted the idea of Maya and denied the possibility of liberation in bodily existence.[128]

Vaishnavism Bhakti Vedanta (12th–16th centuries)

Main articles: Vaishnavism and Bhakti

See also: Bhakti movement

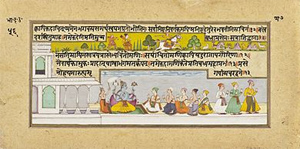

The Bhakti movement of late medieval Hinduism started in the 7th-century, but rapidly expanded after the 12th-century.[129] It was supported by the Puranic literature such as the Bhagavata Purana, poetic works, as well as many scholarly bhasyas and samhitas.[130][131][132]

This period saw the growth of Vashnavism Sampradayas (denominations or communities) under the influence of scholars such as Ramanujacharya, Vedanta Desika, Madhvacharya and Vallabhacharya.[133] Bhakti poets or teachers such as Manavala Mamunigal, Namdev, Ramananda, Surdas, Tulsidas, Eknath, Tyagaraja, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and many others influenced the expansion of Vaishnavism.[134] These Vaishnavism sampradaya founders challenged the then dominant Shankara's doctrines of Advaita Vedanta, particularly Ramanuja in the 12th century, Vedanta Desika and Madhva in the 13th, building their theology on the devotional tradition of the Alvars (Shri Vaishnavas),[135] and Vallabhacharya in the 16th century.

In North and Eastern India, Vaishnavism gave rise to various late Medieval movements: Ramananda in the 14th century, Sankaradeva in the 15th and Vallabha and Chaitanya in the 16th century.

Ramanuja (Vishishtadvaita Vedanta) (11th–12th centuries)

Rāmānuja (1017–1137 CE) was the most influential philosopher in the Vishishtadvaita tradition. As the philosophical architect of Vishishtadvaita, he taught qualified non-dualism.[136] Ramanuja's teacher, Yadava Prakasha, followed the Advaita monastic tradition. Tradition has it that Ramanuja disagreed with Yadava and Advaita Vedanta, and instead followed Nathamuni and Yāmuna. Ramanuja reconciled the Prasthanatrayi with the theism and philosophy of the Vaishnava Alvars poet-saints.[137] Ramanuja wrote a number of influential texts, such as a bhasya on the Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita, all in Sanskrit.[138]

Ramanuja presented the epistemological and soteriological importance of bhakti, or the devotion to a personal God (Vishnu in Ramanuja's case) as a means to spiritual liberation. His theories assert that there exists a plurality and distinction between Atman (souls) and Brahman (metaphysical, ultimate reality), while he also affirmed that there is unity of all souls and that the individual soul has the potential to realize identity with the Brahman.[83] Vishishtadvaiata provides the philosophical basis of Sri Vaishnavism.[139]

Ramanuja was influential in integrating Bhakti, the devotional worship, into Vedanta premises.[140]

Madhva (Dvaita Vedanta)(13th–14th centuries)

Dvaita Vedanta was propounded by Madhvacharya (1238–1317 CE).[u] He presented the opposite interpretation of Shankara in his Dvaita, or dualistic system.[143] In contrast to Shankara's non-dualism and Ramanuja's qualified non-dualism, he championed unqualified dualism. Madhva wrote commentaries on the chief Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutra.[144]

Madhva started his Vedic studies at age seven, joined an Advaita Vedanta monastery in Dwarka (Gujarat),[145] studied under guru Achyutrapreksha,[146] frequently disagreed with him, left the Advaita monastery, and founded Dvaita.[147] Madhva and his followers Jayatirtha and Vyasatirtha, were critical of all competing Hindu philosophies, Jainism and Buddhism,[148] but particularly intense in their criticism of Advaita Vedanta and Adi Shankara.[149]

Dvaita Vedanta is theistic and it identifies Brahman with Narayana, or more specifically Vishnu, in a manner similar to Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita Vedanta. But it is more explicitly pluralistic.[150] Madhva's emphasis for difference between soul and Brahman was so pronounced that he taught there were differences (1) between material things; (2) between material things and souls; (3) between material things and God; (4) between souls; and (5) between souls and God.[151] He also advocated for a difference in degrees in the possession of knowledge. He also advocated for differences in the enjoyment of bliss even in the case of liberated souls, a doctrine found in no other system of Indian philosophy.[150]

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (Achintya Bheda Abheda) (16th century)

Achintya Bheda Abheda (Vaishnava), founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534 CE),[9] was propagated by Gaudiya Vaishnava. Historically, it was Chaitanya Mahaprabhu who founded congregational chanting of holy names of Krishna in the early 16th century after becoming a sannyasi.[152]

Modern times (19th century – present)

Swaminarayan and Akshar-Purushottam Darshan (19th century)

The Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, which is philosophically related to Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita,[153][69][154][v] was founded in 1801 by Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE), and is contemporarily most notably propagated by BAPS.[155] Due to the commentarial work of Bhadreshdas Swami, the Akshar-Purushottam teachings were recognized as a distinct school of Vedanta by the Shri Kashi Vidvat Parishad in 2017[66][67] and by members of the 17th World Sanskrit Conference in 2018.[66][w][68] Swami Paramtattvadas describes the Akshar-Purushottam teachings as "a distinct school of thought within the larger expanse of classical Vedanta,"[156] presenting the Akshar-Purushottam teachings as a seventh school of Vedanta.[157]

Neo-Vedanta (19th century)

Main articles: Neo-Vedanta, Hindu nationalism, and Hindu reform movements

Neo-Vedanta, variously called as "Hindu modernism", "neo-Hinduism", and "neo-Advaita", is a term that denotes some novel interpretations of Hinduism that developed in the 19th century,[158] presumably as a reaction to the colonial British rule.[159] King (2002, pp. 129–135) writes that these notions accorded the Hindu nationalists an opportunity to attempt the construction of a nationalist ideology to help unite the Hindus to fight colonial oppression. Western orientalists, in their search for its "essence", attempted to formulate a notion of "Hinduism" based on a single interpretation of Vedanta as a unified body of religious praxis.[160] This was contra-factual as, historically, Hinduism and Vedanta had always accepted a diversity of traditions. King (1999, pp. 133–136) asserts that the neo-Vedantic theory of "overarching tolerance and acceptance" was used by the Hindu reformers, together with the ideas of Universalism and Perennialism, to challenge the polemic dogmatism of Judaeo-Christian-Islamic missionaries against the Hindus.

The neo-Vedantins argued that the six orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy were perspectives on a single truth, all valid and complementary to each other.[161] Halbfass (2007, p. 307) sees these interpretations as incorporating western ideas[162] into traditional systems, especially Advaita Vedanta.[163] It is the modern form of Advaita Vedanta, states King (1999, p. 135), the neo-Vedantists subsumed the Buddhist philosophies as part of the Vedanta tradition[x] and then argued that all the world religions are same "non-dualistic position as the philosophia perennis", ignoring the differences within and outside of Hinduism.[165] According to Gier (2000, p. 140), neo-Vedanta is Advaita Vedanta which accepts universal realism:

Ramakrishna, Vivekananda and Aurobindo have been labeled neo-Vedantists (the latter called it realistic Advaita), a view of Vedanta that rejects the Advaitins' idea that the world is illusory. As Aurobindo phrased it, philosophers need to move from 'universal illusionism' to 'universal realism', in the strict philosophical sense of assuming the world to be fully real.

A major proponent in the popularization of this Universalist and Perennialist interpretation of Advaita Vedanta was Vivekananda,[166] who played a major role in the revival of Hinduism.[167] He was also instrumental in the spread of Advaita Vedanta to the West via the Vedanta Society, the international arm of the Ramakrishna Order.[168]

Criticism of Neo-Vedanta label

Nicholson (2010, p. 2) writes that the attempts at integration which came to be known as neo-Vedanta were evident as early as between the 12th and the 16th century−

... certain thinkers began to treat as a single whole the diverse philosophical teachings of the Upanishads, epics, Puranas, and the schools known retrospectively as the "six systems" (saddarsana) of mainstream Hindu philosophy.[y]

Matilal criticizes Neo-Hinduism as an oddity developed by West-inspired Western Indologists and attributes it to the flawed Western perception of Hinduism in modern India. In his scathing criticism of this school of reasoning, Matilal (2002, pp. 403–404) says:

The so-called 'traditional' outlook is in fact a construction. Indian history shows that the tradition itself was self-conscious and critical of itself, sometimes overtly and sometimes covertly. It was never free from internal tensions due to the inequalities that persisted in a hierarchical society, nor was it without confrontation and challenge throughout its history. Hence Gandhi, Vivekananda and Tagore were not simply 'transplants from Western culture, products arising solely from confrontation with the west. ...It is rather odd that, although the early Indologists' romantic dream of discovering a pure (and probably primitive, according to some) form of Hinduism (or Buddhism as the case may be) now stands discredited in many quarters; concepts like neo-Hinduism are still bandied about as substantial ideas or faultless explanation tools by the Western 'analytic' historians as well as the West-inspired historians of India.

Influence

According to Nakamura (2004, p. 3), the Vedanta school has had a historic and central influence on Hinduism:

The prevalence of Vedanta thought is found not only in philosophical writings but also in various forms of (Hindu) literature, such as the epics, lyric poetry, drama and so forth. ... the Hindu religious sects, the common faith of the Indian populace, looked to Vedanta philosophy for the theoretical foundations for their theology. The influence of Vedanta is prominent in the sacred literatures of Hinduism, such as the various Puranas, Samhitas, Agamas and Tantras ... [96]

Frithjof Schuon summarizes the influence of Vedanta on Hinduism as follows:

The Vedanta contained in the Upanishads, then formulated in the Brahma Sutra, and finally commented and explained by Shankara, is an invaluable key for discovering the deepest meaning of all the religious doctrines and for realizing that the Sanatana Dharma secretly penetrates all the forms of traditional spirituality.[173]

Gavin Flood states,

... the most influential school of theology in India has been Vedanta, exerting enormous influence on all religious traditions and becoming the central ideology of the Hindu renaissance in the nineteenth century. It has become the philosophical paradigm of Hinduism "par excellence".[20]

Hindu traditions

Vedanta, adopting ideas from other orthodox (āstika) schools, became the most prominent school of Hinduism.[21][174] Vedanta traditions led to the development of many traditions in Hinduism.[20][175] Sri Vaishnavism of south and southeastern India is based on Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita Vedanta.[176] Ramananda led to the Vaishnav Bhakti Movement in north, east, central and west India. This movement draws its philosophical and theistic basis from Vishishtadvaita. A large number of devotional Vaishnavism traditions of east India, north India (particularly the Braj region), west and central India are based on various sub-schools of Bhedabheda Vedanta.[4] Advaita Vedanta influenced Krishna Vaishnavism in the northeastern state of Assam.[177] The Madhva school of Vaishnavism found in coastal Karnataka is based on Dvaita Vedanta.[149]

Āgamas, the classical literature of Shaivism, though independent in origin, show Vedanta association and premises.[178] Of the 92 Āgamas, ten are (dvaita) texts, eighteen (bhedabheda), and sixty-four (advaita) texts.[179] While the Bhairava Shastras are monistic, Shiva Shastras are dualistic.[180] Isaeva (1995, pp. 134–135) finds the link between Gaudapada's Advaita Vedanta and Kashmir Shaivism evident and natural. Tirumular, the Tamil Shaiva Siddhanta scholar, credited with creating "Vedanta–Siddhanta" (Advaita Vedanta and Shaiva Siddhanta synthesis), stated, "becoming Shiva is the goal of Vedanta and Siddhanta; all other goals are secondary to it and are vain."[181]

Shaktism, or traditions where a goddess is considered identical to Brahman, has similarly flowered from a syncretism of the monist premises of Advaita Vedanta and dualism premises of Samkhya–Yoga school of Hindu philosophy, sometimes referred to as Shaktadavaitavada (literally, the path of nondualistic Shakti).[182]