Sivavakkiyam -- Songs of a Spiritual Rebel

by Dr. Geetha Anand and Dr. T.N. Ganapathy

February 25, 2017

About Prof. T.N. Ganapathy

A distinguished scholar, philosopher and educationist, Prof. T.N. Ganapathy, 84, taught philosophy for eight years (1952-60) in the National College, Tiruchirapalli, and for 31 years (1960-1991) in the Vivekananda College, Chennai. He retired from the Vivekananda college as post-graduate professor and head of the department of philosophy.

He was for 15 years (1991-2006) a visiting professor at the Satya Sai Institute of Higher learning [Sri Sathya Sai Baba], Deemed University, Prasanthi Nilayam, Puttaparti.

During his tenure with Vivekananda College, he was awarded a senior fellowship for three years (1985-88) by the Indian Council of Philosophical Research, New Delhi, which published his work The Philosophy of the Tamil Siddhas in 1993.

From 2000, he has been the Director of the Tamil Yoga Siddha Research Centre, Chennai.

He has published more than 50 research papers in prestigious journals in India and Germany. He is considered as an authority on Immanuel Kant and on the Tamil Siddhas.

He has been the founder-secretary of the Tamil Nadu Philosophical Society, Chennai. He has served both as Joint Secretary and as Treasurer of the Indian Philosophical Congress (1979-1985), an All-India body of philosophers.

He was the General Secretary of the Second World Conference on Siddha Philosophy, held at Chennai in December 2008. He was a special invitee to the First World Conference held in 2007 at Kaulalumpur. Malaysia.

He attended the World Tamil Conference held in Malaysia, in January 2015 where his two books in Tamil, Tirumandiram and Sivavakkiyam were released by Kalaignan Pathipagam, Chennai.

He was invited twice by the Centro Integral de Yoga, Santa Ana, 24, Sevilla, Spain to deliver a series of ten lectures on the Tamil Siddhas in July 2015 and ten lectures on the Tirumandiram in July 2016.

He is the author or editor of several books. To mention a few: An Invitation to Logic (1972); Perspectives of Theism and Absolutism in Indian Philosophy (ed., 1978); Mahavakyas (1982); The Philosophy of the Tamil Siddhas (1993); A Pocket-guide to Thesuis Writing (2003); A Bird's Eye View of Hinduism and Indian Philosophy (2004); The Yoga of the 18 Siddhas: an Anthology (ed. 2004); The Yoga of Siddha Bogonathor (2 volumes, 2003-04, also translated into Spanish, Russian and German). The Yoga of Siddha Tirumular (2006). English translation of the Tirumandiram in 10 vols. (2010) (General Editor and Translator of Tandirams 6 and 9.)

He has got several research papers to his credit in Tamil about the Siddhas.

He has been awarded several titles.

About Dr. Geetha Anand

Dr. Geetha Anand is a molecular biologist by training. Her undergraduate training was at IIT Madras and IIT New Delhi. She received her Ph.D., from Purdue University, Indiana. Her post doctoral training was at the University of Pittsburgh. She served as Research Assistant Professor at Childrens' Hospital, Pittsburgh and as Associate Scientist at the Stanford University, California. She was a consultant at the Foundation for Revitalization of local health traditions, Bangalore and at the National Institute of Advanced studies, Bangalore, where she was Mani Bhaumik Scholar under their Consciousness studies program.

She studied Vaishnavism and Indian Philosophy at Madras University. She was awarded first prize in the Srivaishnavism course conducted by Sri Ahobila Math. Her translation of Sri Lakshmi Sahasram by Sri Venkatadvari Kavi and Sri Appaya Dikshitar's Sri Varadarajasthavam can be accessed at http://www.sadagopan.org. She has published several research articles including Nadi Pariksha, Manuscriptology and comparison of commentaries on Charaka Samhita. She is a staff translator of Srimadh Andavan Ashramam's monthly magazine, Sri Ranganatha Paduka. Her translations, Key to Agatthiyar Jnana (Pranav Swasthisthan) and Greatness of Saturn (Kannadasan Padippagam) are in Press.

In the Siddha field, she was a co-author of the article, Monistic Theism of the Tirumandiram and Kashmir Saivism along with Dr. Ganapathy. She has translated several philosophical works published by Babaji's [Sri Sathya Sai Baba] Kriya Yoga Organization. Quebec including The Grace Course, Kailash The Quest of the Self, Kriya Yoga: insights along the Path, books by Sri Kannaiya Yogi, Sri Satchidanada Gwuparan and Siddha Aarakavi's Sambhaviyogam. She is the co-contributor of a monthly featured article in Amman Darsanam, a magazine published by the Sringeri Sarada Mutt, on hitherto unpublished Siddha works. She also contributes original articles for their Deepavali malar and Vardhanthi malar. She runs the blogs http://www.lyricsofthe liberated.blogspot.com and http://www.agatthiyarinanam. blogspot.com where she translates and comments on Siddha verses. Her translation and commentary on Agalthiyar Meijnanam has been translated into Russian. She has published her translation and commentary on Agatthiyar Meijnanam and Subramanyar Jnanam 500 on facebook. She is at present translating and commenting on Agatthiyar's Saumya Sagaram.

PREFACE

T.N. GANAPATHY

The spark that I should translate Siddha Sivavakkiyar's poems into English was placed in my mind by my friends -- a couple Mr. Peter and Mrs. Helen -- who live in Byron Bay at Australia. They visited my house almost every year between 2006 and 2010 (now-a-days I miss them) and we used to go together to Palani Hills to have the darshan of Lord Muruga; they are very pious devotees of Lord Muruga. [the Hindu god of war.]

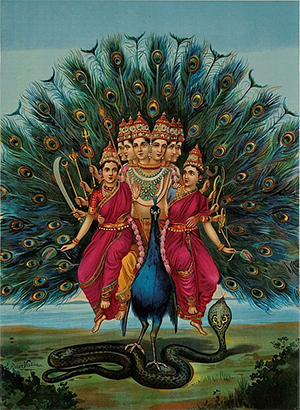

I used to accompany them. since lord Muruga is the first Siddha and guru. Siddhisena is an epithet of Lord Muruga. He rides on the peacock which is considered to be the killer of serpents. Serpent stands for the cycle of births and deaths. Peacock stands for the killer of time and thereby birth and death.

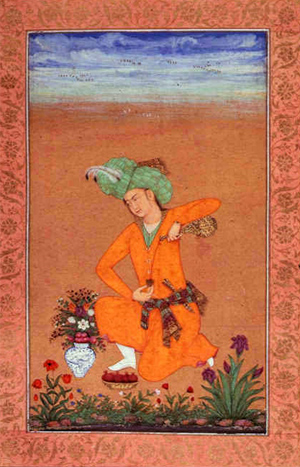

The six-headed Kartikeya riding a peacock with his consorts Valli and Devasena, The peacock is seen trampling a snake by Raja Ravi Varma.

Lord Muruga is also known as Skanda. As long as complete control of semen is not attained in the practice of Yoga, Skanda is not born. According to the tantric tradition when the sexual energy moves to a higher level, changing into a sublimated energy, it awakens the latent Kundalini. This ascetic method of non-spilling of semen is called skanda. Skanda is born only when the semen is sublimated and reaches the sahasrara, the mountain top. Ascending the mountain to reach Lord Muruga is a symbolism for arousing the kundalini and its culmination in sahasrara. The six adharas are the six mountains where Lord Muruga resides, and they stand for the six faces of Him. If one understands this significance of Lord Muruga, visiting Palani or any other mountain is not a mere ritual; it is a yogic, spiritual experience.

During our travel to Palani temple I used to refer to Siddha Sivavakkiyar as a critic of rituals and gave them some sample verses of Sivavakkiyar. One such verse is

With the stone planted as God, placing four flowers on it,

Circumbulating it chanting the mantra under breath what is it?

Will the planted stone talk when the Lord is within?

Will the cooking pot and the ladle know the taste of the dish?

(verse 503)

This prompted Mr. Peter to request me to translate Sivavakkiyar's poems. I was waiting for an occasion and in the year 2011 Dr. Geetha Anand who lives in Bengaluru came into the picture by the grace of the Siddhas. Both of us translated the poems of Sivavakkiyar as early as 2012 and was waiting for a publisher to take up the work. No publisher came to our rescue fearing financial loss. In the meanwhile my good friend Sri Govindan Satchitananda, founder President of the Babaji's Kriya Yoga order of Acharyas, USA. Inc, Quebec, Canada, came across our work and he published it in the internet, duly acknowledging our copy right, and this became viral and it has been translated into Russian (by Konstantin Serebrov, a yoga teacher and writer/author in Moscow) and into Spanish (by Professor Ramon Ruedas, Professor De Yoga of the Centro Integral de Yoga, El Malino, Sevilla, Spain) for exclusive use by the disciples in their yoga schools.

Just as Sivavakkyar has not followed the tradition we two have also transgressed the tradition of having only one foreword to a work.

Dr. Geetha and myself have got four forewords for this work of translation, one from an Indian Professor of Philosophy, Dr. Kamalakar Mishra, Professor and Head (retd.), Dept. of Philosophy and Religion, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India, the second from a well-known American Yoga practitioner and Acharya Mr. Marshall Govindan, President, Babajj's Kriya Yoga Order of Acharyas, Inc., Quebec, Canada, the third from a Spanish Yoga Guru, Mr. Ramon Ruedas Gomez, who runs a yoga ashram called Ashram Vettaveli, at Centro Integral de Yoga, Sante Ana, 24 Sevilla, Spain, and the fourth from a Russian Yoga practitioner and teacher Mr. Konstantin Serebrov, Moscow.

Each Foreword is a class by itself, and we thank immensely the four foreword writers.

In June 2016, one of my friends from Singapore, Sri N.C. Prakash, came forward to help me in the publication of this important work and donated a sizeable amount to start the publication. Hence this publication. I do not have adequate words in my vocabulary to thank him for his voluntary, instant donation. All this is due to the blessings of the Siddha Sivavakkiyar. Now the book is in your hands for spiritual enjoyment.

Foreword - 1

The Truth of the Siddha Tradition

by Dr. Kamalakar Mishra, Professor * Head. (Retd.). Dept. of Philosophy & Religion, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

The most significant contribution of the Indian tradition to the world-wisdom is that the Indian seers who can be aptly called "spiritual scientists" have discovered or found out, experientially and experimentally a state of inner consciousness which is the natural source of power, wisdom, happiness and beauty in life. It is the state of the "Self' -- of course the "Higher Self (Parama-Atma)". The seers investigated into the nature of the self (the "I") addressing the question -- "who am I?" They discovered that the real nature of "myself" (the "I") is divine, that I am separated from my true Self due to the obstruction or veil of spiritual impurity and that I can reattain or realize my divine nature following the path of self-purification and universal love. My existential self (which can be called the "surface" self) is part of, and substantially one with, the divine Self which lies deeper within me. I have double citizenship, so to say, I am the citizen of the world terrestrial and also the citizen of the world celestial.

What is given by the seers is not a matter of speculation or a matter of faith; it is really the discovery of finding of the truth of the Self, it is the actual cognition of the truth as it is the actual experience of the seers. This makes the significance of the knowledge of the seers unique and extremely important and also puts it in the category of scientific discovery. A more significant point is that this Self (inner Self) is also the state of natural synthesis between what is called sreya (the good) and preya (the pleasant). Indians had long realized that if the philosophy of life is mere sreya say, of sheer asceticism, literal renunciation (sannyasa), torturous penance (tapasya) and mindless self-abnegation, then this may remain an impracticable and painful ideal. Since the ascetic ideal involves suppression of desires (including sex desire), it may cause psycho-neurotic problems (both in the individual life and in the social life). It may also create hypocrisy in life. But if, on the other hand, we follow the life of mere preya that is, the life of hedonistic enjoyment of carnal pleasure (bhoga) then we would be reduced to animals, and there would be no human society worth the name. Moreover, the hedonistic life ultimately becomes suicidal. Hence, the seers were in search of a state of consciousness which is ideally perfect, that is, it is all goodness on the one hand and all happiness or sukha (joy of pleasantness) on the other hand. The answer was found in the spiritual life which is the life of the self. In the spiritual state all the desires (specially the most problematic sex-desire) are transformed or sublimated into pure love and this in turn brings deep satisfaction and Ananda. This is a state of goodness and pleasure (Ananda) -- the two in one.

It should also be noted that the Self is not confined in the body. It is ubiquitous, all pervasive. Everything and every being of the world is incorporated within the Self. Therefore, the person who realizes the Self, realizes his/her unity with the whole world. In the Self-realized persons the feeling of "otherness" (Dvaita-bhava or Bheda-buddhi) is totally absent; they become one with all being (sarvabhutatma- bhutatma) and naturally therefore they wish and do good to all people (sarvabhutahiteratah). This position may be put the other way round also, that is, one who feels one's unity with all the beings and follows the path of universal love, attains the Self. The Self cannot be realized by isolating (cutting off) oneself from the society living in segregation and going on meditating inside the body. For realizing the Self one is required to expand oneself into all beings. That is why for Self-realization the saints and Siddhas have advocated the path of universal love and not the path of isolation and renunciation. They themselves have attained Self-realization through universal love. Love is the very nature of the Self. The more we realize the Self, the more the love naturally emanates and the more we love the more we come nearer to the Self. Self-realization and universal love are reciprocal.

In the Semitic tradition, God is conceived as wholly transcendent. God lives in heaven as "other" to man. The renowned Christian theologian, Rudolf Otto, calls God the "Holy Other". But in the Indian tradition God is conceived as substantially present in everything, as the world is the manifestation of God Himself. Moreover, God is our own self -- the Higher Self. The term Paramatma (Parama+Atma) which is the synonym of God, is very significant. Parama means the higher and Atma means the Self. So, God means the Higher Self; realization of the Self and realization of God mean one and the same thing....'[missing the rest].

1. Introduction:

“cittar civatthaik kandavar” A Siddha -- one who has “seen” Siva.

Tirumular, in his Tirumandiram, defines a Siddha as one who has “seen” Siva. If this is so then who is better qualified to talk about Siva, talk as Siva, or utter “Siva statements -- Sivavakkiyam” other than a Siddha, Sivavakkiyar! Just like the Maha vākhya or supreme statements, Tat Tvam asi (that are thou) and Aham Brahmāsmi (I am Brahmam), Siva vakkiya (Sivavakkiyam in Tamil) is about Siva, the Universal consciousness, the Truth, the Ultimate Reality.

As it is with most of the Siddhas, nothing much is known about Sivavakkiyar or his life history. A verse from Sage Agastthya offers a reason for why this is so. According to him, most of the Siddhas’ works were lost in the floods and only a small collection of them were preserved. Also the Siddha poetry in circulation now is only a distortion of the original poems. Hence, great caution should be exercised while giving historical and biographical information on the Siddhas. Besides, the Siddhas were adepts who could enter another body at will. Thus, it is difficult to say “who is who” let alone give a biographical account of them. Also, one finds that more than one Agatthiyar or Pattinattar are referred to in Tamil literature. This shows that most of the names of the Siddhas are acquired ones.[!!!]

Many names of the Siddhas are symbolic. According to tradition, each Siddha receives five different names, the first one given by the parents and the remaining four are appellations for the stages in the spiritual progress attained by the person concerned (1). Among these four names is the name given by the guru (the spiritual teacher) at the time he initiates the disciple. The name Agatthiyar means one who has kindled the inner fire in him (agam= inner, ti= fire) that is, one who has roused the fire of kundalini in him. One who has conquered sex and anger is called Gōraksha. Matsya means fish. In Tantra it stands for senses. Matsyendranāth means one who has mastery over the senses (indriyas). It represents one who has torn the fetters of bondage. In the same manner one may construe the name Pattinattār as Patti+nāttar, that is, a man who can save the souls. Patti in Tamil means “the pound (enclosure) for herding the cattle;” it may also mean, “herding of souls”, souls wallowing in the darkness of ignorance. Pattinattār is one who helps and guides these souls by providing a method to get out of “the world and the senses”, to get liberated. The name, Sivavākkiyar is an acquired one too. It was probably given because he used the word Sivāyam in more than sixty places in his work. The above discussion shows that it is very difficult to have an authentic account of the life of the Siddhas. Yet, in some works, one finds certain account of the biographies of the Siddhas.

First of all it is to be noted that in the several lists of the Tamil Siddhas (2) the name Sivavākkiyar is not found[!!!] since he was considered to be a “rebel” and in his poem there is “a grand remonstrance almost against everything that was held sacred in his time.” Yet he was neither an atheist nor an agnostic. He was “a pious rebel” or a “spiritual rebel” whose poems have an element of unsophisticated bluntness. “There is a forceful clarity, shocking us sometimes by its forthright directness; he is not even afraid of using terms that prigs will call vulgar or obscene” says T.P. Meenakshisundaram in his book History of Tamil Literature (3). Further, there is a charge of vulgarity against him which is based on his constant reference, in a contemptuous tone, to sex and the biological facts of human birth. Sivavākkiyar was fond of using only the common words spoken by ordinary people -- unpolished, crude, offensive, indecent and colloquial expressions. Vellaivaranar goes to the extent of calling the languages of the Tamil Siddhas (and we may very well adopt it to Sivavākkiyar’s language) as “slum language” -- sérimoḻi yenppadum péccu vaḻakku (4). These may be the reasons for his name being omitted in some of the lists of the Tamil Siddhas.

The text that Ziegenbalg most often quotes to illustrate Indian monotheism was already used by de Nobili for the very same purpose: the Civavakkiyam, a fourteenth-century collection of poems by Civavakkiyar who belongs to the Tamil Siddha tradition.

Although the Tamil tradition speaks of eighteen Siddhas and posits a line of wandering saints and sannyasis from Tirumular (sixth century) to Tayumanavar (1706-44), most of the noted Siddhas flourished between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries (Kailasapathy 1987:387). From the beginning, the antibrahmanical and antihierarchical tendency of Siddha writings was prominent...

Of the more than fifty names associated with the way of the Siddhas (Siddha marga), that of the author of the Civavakkiyam (Aphorisms on Shiva) is best known. The author of these aphorisms, Civavakkiyar or Sivavakkiyar, is "without doubt the most powerful poetic voice in the entire galaxy of the Siddhas" and is best known for his skill in criticizing and ridiculing Hindu orthodoxy (p. 387-89). Though not forming a well-defined school of thought, the Siddhas "challenged the very foundations of medieval Hinduism: the authority of the Shastras, the validity of rituals and the basis of the caste system" (p. 389). According to Zvelebil, "almost all of them manifest a protest, often in very strong terms, against the formalities of life and religion; denial of religious practices and beliefs of the ruling classes" (1973:8).

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

1. About Sivavākkiyar’s life:

Factual information such as dates of birth and death, the real name of the Siddha, the village where he was born, the caste in which he was born and the place where he lived cannot be obtained (5). In this connection mention may be made of M. Arunachalam’s interpretation of the term ‘pāychalūr’ in the songs of Sivavākkiyar (6). He construes pāychalūr as a place and connects it with Sivavakkiyar’s birth as being born of a Brahmin father and a harijan mother and feels that the mention of pāychalur in the songs of Sivavakkiyar may be fully autobiographical and connected with the Pāychalur Ballad’ (7). But a careful examination of M. Arunachalam’s thesis will show that it cannot hold water for the following reasons:

It would become a self contraction [contradiction?] to uphold this view since M. Arunachalam in the article under reference has categorically stated: “nowhere do we find any autobiographical touch in their (Siddhas) songs as we find in the songs of the saints. (The word Siddha in brackets is mine).

The term pāychalūr does not refer to any place but to what happens in yoga, i.e., it stands for the gushing kundalini passing through the ādhārās. Pāychalūr is the gushing place of the kundalini sakti at the cakras. In Tamil Siddha literature kundalini is called a horse, puravi to indicate the galloping force of the kundalini energy as it passes through the ādhāras. This term found in verses 353, 364, 369 of Sivavakkiyam is closely connected only with yoga methodology and does not stand even by the remote possibility for any place on earth. The word pāychalūr which occurs in verse 594 of Tirumantiram also refers to the yoga method. This is an instance of the intentional language of the Siddhas, which is veritable Serbonian bog into which an army of philosophers have fallen and sunk.

Serbonian Bog was an area of wetland in a lagoon lying between the eastern Nile Delta, the Isthmus of Suez, Mount Casius, and the Mediterranean Sea in Egypt, with Lake Sirbonis at its center....The bog is used as a metaphor in English for an inextricable situation.

As described by Herodotus, Strabo and other ancient geographers and historians, the Serbonian Bog was a mix of genuine sand bars, quicksand, asphalt (according to Strabo) and pits covered with shingle, with a channel running through it to the lake. This gave the wetlands the deceptive appearance of being a lake surrounded by mostly solid land....

According to Diodorus Siculus, most of the army of the King of Persia was lost there after his successful taking of Sidon in his attempt to restore Egypt to Persian rule.

-- Serbonian Bog, by Wikipedia

It is said that Sivavākkiyar acquired this name because when he was born he came into this world uttering the name “Śiva” This is the view expressed in Abithana Cintāmani (8). There is a view that before he became a Siddha he embraced Buddhism for a few years. Similar views such as that he was closely associated with Islam and Christianity are to be taken only with a pinch of salt. Since there is a close similarity between some stanzas of Sivavākkiyam and those of Tirumalisai Alwar’s Tirucchandaviruttam it is believed that Sivavākkiyar and Tirumalisai Alwar may be one and the same person.

Thirumazhisai Alvar (Born: Bhargavar 4203 BCE - 297 AD) is a Tamil saint revered in the Srivaishnavism school of south India, in Tondai Nadu (now part of Kanchipuram and Tiruvallur districts). He was born in 4203 BCE. The legend of this saint devotees of Srivaishnavism believe that he was the incarnation of Vishnu's disc, Sudarshana.

Sudarshana Chakra is a spinning, discus weapon with 108 serrated edges, used by the Hindu god Vishnu or Krishna. The Sudarshana Chakra is generally portrayed on the right rear hand of the four hands of Vishnu, who also holds a shankha (conch shell), a Gada (mace) and a padma (lotus).

-- Sudarshana Chakra, by Wikipedia

He is believed to have been born at Jagannatha Perumal temple, Tirumazhisai by divine grace.

A childless tribal couple called Tiruvaalan and Pankaya Chelvi engaged in cutting canes found the child and took it home. The couple also had a son named Kanikannan who was a disciple of Thirumazhisai Alvar.

Thirumazhisai Alvar proclaimed that he didn't belonged to Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya & Shudra in one of his couplets as he was considered (Avarna) beyond caste bound person. He was the only azhwar saint who lived for 4500 Years....

The name of the Azhwar comes from his birthplace, Thirumazhisai, a suburb in modern day Chennai.

According to Puranas, it was the onset of Kali Yuga (the dark age). Lord Vishnu was worried about the next incarnation his weapon to take because, Kali Yuga has started and he didn't know how his relations will spend their life on Earth since they had to spend a normal Human life. It was the onset of Kali Yuga, and Vishnu was worried about this and when enquired he told the terrible attitudes of people during the Kali Yuga and how can his dear ones can spend their life on Earth in such a dark age, when Sudarshana intervened and volunteered to be born on Earth when Vishnu objected again exclaiming the attributes of Kali Yuga. Sudarshana still obliged leaving Vishnu tearful. He had a weird birth story. This was when Bhargava maharishi was in a long tapa (penance) to please Vishnu, as usual to spoil his penance Indra sent an apsara for which he succeeded. After enjoying worldly pleasures the apsara left to heaven leaving back the baby born to them. Due to his attachment to continue the penance, he cannot take care of the child and left it on the ground. Many days passed and the baby was crying a lot and nobody turned around to look after him. He was covered with blood and worms and mosquitoes are continuously biting him. Worried, Vishnu and Lakshmi descended to Earth and touched the baby and disappeared. The baby was transformed into a handsome young boy. The boy being Sudharshana Chakra himself was devoid of any illness though was hungry for many many days. All were wondering how could this be possible when a childless couple adopted him. Even then he did not accept single grain of rice from the couple. One day, an old man and woman paid visit to this boy. The boy was happy to see them when they asked to go for a short walk along the temple premises. The boy obliged and the old man and woman seemed worried and when enquired, they answered that the sadness cannot be prevented in that age. Still he enquired to which the old couple answered they are yearning for parental affection, to which this boy seemed too casual and wrote two pasurams in praise of Vishnu and miraculously the old couple was transformed into young and good looking couple. They thanked the boy a lot and this boy was too happy because in the Kali Yuga period people are also being thankful to which he wrote another pasuram in praise of Lord Vishnu. The boy asked the couple to read the pasuram, and the couple was blessed with a baby boy whom they named as Kanikannan. Kanikannan grew up to be a disciple of the boy. One time, after the demise of the couple, knowing about the glory of the boy and his disciple Kanikannan, the jealous chola king who was a strong shaivaite ordered him to sacrifice Vaishnavism and practice Shaivism to which they declined, and accordingly they were subjected to death. Somehow both escaped the place to Srirangam. Another news reached their ears that they (the boy and Kanikannan) must be killed or must be exiled, if found anywhere. Worried, they visited all Vishnu temples in Tamilnadu, and when they paid the tributes to Ranganatha Perumal in Srirangam, one amazing and miracle happened. The statue of Ranganatha woke up and stopped these two, and they declined stating it is a duty for the citizens to obey the order of their ruler. Next, they both visited Kumbakonam Sarangapani temple, and the statue again rose, and this time both obliged and merged with the lord. To be a proof of future generations that the idol actually rose up, Vishnu's head in Sarangapani temple is raised a bit. The boy was called Thirumalisai Alvar thereafter....

He also has an eye on his right leg.

-- Thirumalisai Alvar, by Wikipedia

The life of Sivavakkiyar is given in a Tamil work called Pulavar Purānam by Murugadāsa Swamigal. Another work called Pulavar carittira Deepakam summarizes the traditional accounts about the life of Sivavakkiyar. We may sum up by saying that the biographical history of Sivavakkiyar is often based entirely on word of mouth accounts and therefore is not always readily available (9). If available it is not authentic, for it is mixed only with local mythology and sentimental accounts. About the time when he lived, we may safely say that he lived during the 15th century A.D.[???!!!] As far as we are concerned, what Sivavakkiyar said is more important than what and where he said it, where he was born etc.[???!!!]

Sivavakkiyar does not specifically mention his guru parampara or lineage in his work (10). The only hint available is in verse 301 where he says “with the sacred feet of Mūlan who said the three, ten and the three as three I would say the five letters”. If the Mūlan mentioned here refers to Tirumular, the composer of Tirumandiram, he may be indicating to us that he belongs to the mūlavarga, the lineage that claims Tirumular as its preceptor. Then again, the Mūlan may very well refer to the Ultimate Reality, the root cause, the mūlam, of everything.

According to cittar tradition, Tirumūlar, the early Śaiva mystic and author of the Tirumantiram, is said to have been the disciple of an alchemist named Nantikēcuran.171b) ff. 1-12 Tirikālacakkaram.

The Puvanacakkaram deals with the measurement of the earth by Nantikēcuran. The Tirikālacakkaram (‘revolving wheel of the three times’) contains a summary of South Indian cosmology and mythology. It is ascribed to Tirumūlattēvar (Jeyaraj, p.330).

-- The Bayer Collection, A preliminary catalogue of the manuscripts and books of Professor Theophilus Siegfried Bayer, acquired and augmented by the Reverend Dr Heinrich Walther Gerdes, now preserved in the Hunterian Library of the University of Glasgow, by David Weston, 2018

Tirumūlar is also closely connected to Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai, where he took physical form by entering the body of a cowherd and composed the Tirumantiram. It is, however, not clear that an ascription to this early Tirumūlar is intended in Ziegenbalg’s account of the work. Zvelebil gives the briefest details of an undated Tirumūlatēvar, ascribing to him three works: the Tirumantiramālai, Tirumūlatēvar pāṭalkaḷ and Vālaippañcākkara viḷakkam. Tirumantiramālai is in fact the full title of Tirumūlar’s Tirumantiram and hence the distinction between the work which Zvelebil ascribes to Tirumūla Tēvar and Tirumūlar’s own work is not clear. We have not been able to identify copies of the Tirumūlatēvar pāṭalkaḷ and Vālaippañcākkara viḷakkam, but the title of the latter suggests a work on the five-syllable nama-civāya mantra. There are a number of works of this kind, with different titles, closely associated with the Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai maṭam. Whether Tirumūlar or Tirumūla Tēvar is intended, an association with Tiruvāvaṭutuṟai certainly cannot be ruled out.

-- Bibliotheca Malabarica: Bartholomaus Ziegenbalg's Tamil Library, by Will Sweetman with R. Ilakkuvan

2. About Sivavakkiyam:

There is a general confusion about the number and order of verses of Sivavakkiyam. The version published by Aru. Ramanathan in the collection of Siddhar Padalgal (10) consists of 533 songs. The publication from The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing society, Tinnevelly (1984) has 526 verses. B. Ratna Nayakar sons (1955) have published a version which contains 1012 verses. The last publication has verses on Siddha medicine and recommendations for curing fever besides several unrelated topics. These verses do not fit with Sivavakkiyar’s original intent and hence seem to be insertions at a later date.

Aru. Ramanathan’s publication was used as the source for this research work. Verses that were repetitions have been taken into consideration while numbering them. Translation and a commentary on individual verses is available as an e-book, “Truth Speaks by Yoga Siddha Sivavakkiyar at http://www.babajiskriyayoga.net/english ... kiyam_book.

3. About Sivavakkiyar’s teachings:

The āṛṛuppadai concept that we find in Tamil literature has acquired a social- philosophical meaning at the hands of the Tamil Siddhas, especially with Sivavākkiyar. Āṛṛuppadai means “showing the path to the people”. This concept has two aspects in the teachings and philosophy of Sivavākkiyar- one positive and the other negative. In the negative aspect, Sivavākkiyar emphasizes “what one shall not do” in order to achieve self-realization. The concepts he admonishes are spiritual and social hypocrisies. In his list of “what one shall do” he recommends Siva yoga, respecting the guru, offering alms to the needy and living a life seeking realization. He not only gives a philosophical exposition on the concept of pati, pasu and pāsam but also a procedure to reach the state of realization, the state of Siva. He begins his composition stating clearly that he will be describing the rare mantra namacivaya which is the origin and terminus of everything, the mantra uttered by millions of celestials before, the “siva sentence” and that he plans to do so by contemplating on the curved letter (aum) so that sins and delusion will run away. Let us see below some of the sins and delusions that Sivavakkiyar wishes to chase away.

a. Sivavakkiyar’s dismissal of spiritual and social hypocrisies:

Sivavākkiyar vehemently reprimands practicing caste-based and gender-based discrimination, performing rituals mindlessly, cheating people in the name of spirituality/religion and holding on to illogical practices.

b. Caste-based discrimination:

“Who is a low class woman, who is a rich woman? Is it marked on the flesh, skin or bones?” he asks (verse 39). He even goes to the extent of asking, “Is enjoying a low class woman different from enjoying a rich woman?” He further comments that when one looks critically at a rich woman and a low class woman, one would realize that they both are none other than limited consciousness which is free from caste, creed or even gender and hence one should shun the evil practice of discriminating people based on their caste.

Sivavakkiyar brings up another situation to ridicule caste-based discrimination. He says that if a buffalo copulates with a cow, the offspring is a hybrid. It looks neither like the cow nor the buffalo. However, if a man born in a higher caste copulates with a lady from a low caste, the offspring is still a human child. He asks people how they are justified in talking about the offspring as different when it looks the same, as a human being! (verse 467). His intense satire is displayed when he says that everything in this world is nothing but semen, only fluid with motion (verse 46) and so people should look forward to the day when they will burn the manudharma sastra which preaches caste-based differentiation (verse 468). According to him all the Vedas, Agama, natural elements and scriptures only breed duality and discrimination. Hence, one should go beyond them and realize the truth (verse 469).

Besides dismissing the general caste-based discrimination, Sivavakkiyar scoffs at the Brahmins who claim that they are superior as (a) they do not eat meat or fish, (b) bathe in sacred waters and (c) perform twilight worship ritual. He sarcastically remarks that it is the same water where the fish resides that the Brahmins use for bathing and drinking, the skin of the deer is customarily tied to the sacred thread they wear on their chest, the goat’s meat especially the intestines is used as fire offering and the beef is used as fertilizer for plants by all (verses 157, 158). He asks them whether the loin cloth they wear, the sacred thread and the tuft they adorn accompanied them from the time of their birth or whether the four Vedas occurred in their minds when they were born (verse 192). He remarks with great distaste that the show they put up with their adornment, the fragrance, the lamps and the articles of worship, is like a butcher spreading the pieces of goat meat for sale. He asks them what kind of worship it is that they are supposedly performing (verse 194).

He comments about a common practice among Brahmins, the sandhyāvandanam or worship during twilight. Twilight is the meeting point of day and night. The day (light) represents wisdom while the night (darkness) represents ignorance. Sivavakkiyar says that when one raises the vital breath through yoga, one will be performing this twilight worship as one will reach the meeting point of ignorance and wisdom, the junction between the limited soul and the universal soul. This is the real twilight worship, not the temporal action (verse 473).

Sivavakkiyar also talking about another common practice where people clean their mouths from spit by drinking more water and spitting it out. Sivavakkiyar wonders how the same water in the mouth removes the same water, the spit. He asks “aren’t all the mantras spit as they are recited by the mouth?” (verse 465). People through away the stone dish they eat on claiming that it has been tainted with spit. Sivavakkiyar questions “what would you do with the hand that ate the food? Even the Gods eat the same way isn’t it?” He says that everything in this world is tainted by the Divine. All the scriptures, the mantras, knowledge systems, the bindu (the primordial point of emergence) and the wisdom, everything carries traces of the Divine (verse 41). All the life forms are also impure as the water element, the seminal fluid, causes their emergence (verse 149). The sacred honey used in worship rituals is tainted by the bee’s spit and the milk collected by milking the cow is tainted by the hand that collects it (486). There is nothing in this world that is not tainted. Practicing untouchability is hence, ridiculous.

c. Gender-based discrimination:

Some of the Siddha verses seem to demean women. They are referred to as objects of desire, distraction and ghosts who pull one into worldly life. Sivavakkiyar dispels the belief that the Siddhas are against women. He says that there is no one in this world who has not associated himself with a woman. He says that people’s life improves when they associate with the right woman. He adds weight to his statement by stating that Lord Siva is adorning River Ganga on his head for this very same reason (verse 512). He praises family life by saying that remaining as a tapasvin in the forest consuming dried leaves will only torture the body while leading a family life where one shares his food with guests is the best. He remarks that God will voluntarily come to that person’s house as a guest and bless him (verse 515).

Just as how it is illogical to consider the Brahmins as superior, it is foolish to consider women as lowly and impure because they menstruate every month. Sivavakkiyar laughs at this hypocrisy saying that the menstrual cycle is nothing but God’s step for creation. He says “You were in the womb that contained the defilement. When you found the way to emerge and came into this world you were (coated) with the same fluid. You emerged (from the fluid) from such a situation and are now reciting countless Vedas. Isn’t it the defilement that assembled and became a form, even that of a guru? Did any life form emerge in another way in any of the worlds?” (verses 48,49,50, 134, 137). In the verse 212 he describes how a life occurs in the womb. The menstrual fluid in the mother’s womb terminates its cycle for ten months, adorns the semen and becomes like a dewdrop. It remains within the fluid taking a form developing its limbs and other parts until it is born later. Besides, showing the satirical attitude of Sivavakkiyam, these verses tell us that the Siddhas were well aware of how a fetus is formed and how it grows in the uterus. Sivavakkiyar seems to be not only a Siddha but a scientist as well!

d. Spiritual hypocrisies:

After condemning social hypocrisies, Sivavakkiyar attacks spiritual hypocrisies such as mindless recitation of scripture, performing elaborate and showy worship rituals, running from one so called sacred place to another and from one so called sacred water body to another.

Sivavakkiyar speaks strongly against the practice of mindless recitation of scriptures. He says that reciting the four Vedas faultlessly smearing the sacred ash on one’s forehead will not reveal the Divine. Only when the heart melts with true devotion and merges with the truth within, saying that one’s upkeep is completely the Divine’s responsibility, when one surrenders to the Divine completely, will one merge with the effulgence, the Lord, the Supreme Being (verse 105). He makes fun of those who engage in mere recital of scriptures by saying that when wheezing and sweating occur portending death mere scriptural knowledge will not help. One needs pills, māttirai. Probably, he makes a pun on this word by saying that if at least for a māttirai, a moment, one realizes and contemplates on the Divine, the diseases caused by the baggage of empty scriptural knowledge will not trouble one (verse 13). He calls people who seek textual knowledge as those who are searching for butter while the curds are remaining in the house (verse 75). He remarks with great disappointment that it is impossible to live with such fools.

Among the Tamil Siddhas we find Sivavākkiyar in particular condemning idol worship tooth and nail. He chides people saying that they are “cleaning the bell, taking the oral secretion from the bees and pouring it over a broken stone” (verse 33), “the whole town is getting together and pulling with a rope, a piece of copper placed on a chariot” (verse 242). He remarks that God is not in “brick, granite, red paint of mercury, copper or in spelter” (verse 34). He points out a situation where one stone is broken into two; one half of it is place at the entrance of the temple as a stepping stone and the other inside the sanctum as the object of worship. He asks whether there is any difference between the two (verse 429). He points out yet another situation where Godhead is made from the same tree branch that is used to make footwear. “Is there is any difference between them?” he asks (verse 527). He questions people whether a “stone planted as God with four flowers placed on it and circumambulated while chanting mantra talk, while the Lord is really within” (verse 503). He says that he could only laugh at such people who think that God is stone (verse 129).

He advises people that “The Lord made of wood, the Lord made of stone, the Lord made of coconut shell, the Lord made of turmeric, the lord made of cloth, the Lord made of cow dung are all none other than the supreme space.” (verse 517). He asks people why they are running to another place thinking that God is “there” and not “here”. He asks them, “If God is only there, then where does he live and how does he remain there?” He advises people that the only place where they will find the Lord is in the letters ci and a that represent mental clarity and ubiquity respectively (verse 431). Sivavakkiyar, in short, is against idol worship because his aim is to have that experience directly instead of feeling something about that experience. Idol worship, according to Sivavakkiyar is a negation (not a substitute) of genuine religious experience. He is one with the Baul of the Bengal who sing that the road to God is blocked by churches, mosques and temples (23). We find the echo of the same views in Ganapatidasar’s poems (verses 15, 63 and 75) Agasthiyar Jnanam- 4 (verse 5) and in Valmigar Jnanam (verse 4). Their aim is to have the religious experience directly instead of feeling something about the experience.

People consider rivers such as Ganga, Yamuna, Cauvery and temple tanks as sacred water bodies and bathe in them submerging themselves there. He asks people, “If they such an action will confer liberation, what will the toad that remains in the water day and night attain?” (verse 130). In this connection one is reminded of one of the verses of Kalin. He says that if bathing in the Ganga ensures liberation, then the fish that live permanently in Ganges are more appropriate candidates for liberation than once in a lifetime bathers are.

To the Tamil Siddhas the real temple and real thirtha (as thresholds of religious experience) are not outside but inside the individual. The place where the Lord resides is the temple. ‘koil= ko+il’. The residence of the Lord is the heart as the Divine is immanent. The antaryami form or the divine as the indweller is the supreme form of the Lord as in that form he functions as a witness and a guide- a guru within. Such a location of the Lord is beyond creation and destruction unlike the material temples and tanks. Instead of realizing this, people are engaged in all sorts of sacrifices, offerings and visiting water bodies as if they are sacred. It is not that Sivavakkiyar condemns performing worship rituals. He says that one should perform them with clear understand instead of merely cleaning the place, smearing sacred ash on oneself and performing austerities (verse 479).

Some people indulge in a practice wherein they offer goats, chicken and gruel to their family deity, usually Kali, to ward off their diseases. They believe that the deity consumes these, gets pacified and fixes their diseases. Sivavakkiyar questions how this can be true (verse 518). An authentic God, especially one’s family deity, will never let one waste away like this. It will never get angry with the person but help him get out of his difficulties. Some people also perform esoteric worship rituals to appease ghosts and goblins expecting them to grant them various benefits or overcome some ailment. Sivavākkiyar questions whether any such ritual- based worship is valid at all. Neither the ghosts and goblins accept this worship nor does the Ultimate Reality, the primal eternal One accept the offerings. It is actually the priest or the man who performs these rituals who enjoys the things offered. All these worship rituals are hence useless (verse 252).

Sivavākkiyar does not leave us with only the ridicule but with a practical suggestion for how to perform austerities. In verse 199 he says, “Flower and sacred water are my mind, fitting temple my heart, the soul spreading as all-pervading lingam the superior five as fragrance and lamp, for the supreme dancer there is no dawn or dusk ritual.” Worship within oneself if far superior to any other external worship ritual. He says that one should get up early in the morning and through the eye of discrimination/knowledge, the third eye, one should contemplate on the Absolute. Only this will grant liberation (verse 130). The third eye is popular not only in the Eastern traditions but also in several Western traditions. The third eye, also known as inner eye, refers to the ajna cakra in the middle of the eyebrows. It is considered as the gate that leads one to higher conscious states. It symbolizes enlightenment, a state of non-dualistic perspective. The time between 4 AM and 5.30 AM is called the Brahma muhurta or the time of Gods. Waking up at this time for sādhana is highly recommended.

e. Condemnation of charlatans:

One of the common problems that a spiritual aspirant faces is being taken for a ride by charlatans who pose as guru or realized souls. Sivavakkiyar lists the types of cheats that people should watch out for. He grades them based on how seriously they trick people.

The most common swindlers are those who pose as priests and soothsayers offering to perform rituals that would expiate one’s sins and thus relieve one from bad situations in life. These crooks prey on people’s fears. They adorn themselves elaborately with sandalwood paste and sacred ash; they wear the black soot from the homa on their forehead and act as if they are pious god men. Sivavakkiyar says that these charlatans are interested only in other people’s money. He curses them saying that they will wallow in the most torturous hell; they will be cut up like a warhorse and burnt to cinders (verses 519, 520).

The next type of cheats prey on people’s greed. They pose as experts of alchemy and delude others by saying that they can turn base metal into gold. They demand materials and money from others. Sivavakkiyar says that these cheats will collect all the wealth and run away not to be seen ever again (verse 521).

The third type of cheats use people’s beliefs. They pretend to be yogis who can levitate. They will try to impress others with shows of insignificant magical prowesses. Sivavakkiyar says that this category of cheats will lose themselves seeking physical pleasures and women (verse 522). These days, our newspapers are full of stories about these babus and gurus. Sivavakkiyar’s study of people and their character is truly amazing.

I read the story of Sai Baba, the Indian guru, written by Michelle Goldberg.[/url] I had contributed what I know about Sai Baba and his pedophilia to this story, and I wish to add that I had represented this matter to the U.S. Department of State, and the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, which asked me to assist the FBI in its fact-finding mission.

I met with the FBI officers in Chicago, and gave them more than 100 pages of sworn affidavits from victims of sexual abuse from all over the world, many of them from U.S. citizens, including minors.

The FBI, after consulting with the U.S. attorney's office, has sent the Sai Baba case to the Department of Justice in Washington, where it has been sitting for the past three months with no further action so far.

Sai Baba is a dangerous pedophile in the guise of a guru, and enjoys the active support of top Indian political leaders including Prime Minister Vajpayee. Sai Baba's organization is worth about $1.5 billion worldwide, and enjoys tax-exempt status in the U.S.

It seems rather likely that the U.S. government, under diplomatic pressure from the top levels of the Indian government, are soft-pedaling the Sai Baba matter, to save the top Indian leadership from being discredited.

Because pedophilia is one of the most evil crimes, shocking the conscience of every right-thinking human being, U.S. citizens, media, legislators and law enforcement officials should ensure that maximum effort is taken in making the Indian government do what it should do: investigate and prosecute Sai Baba.

The U.S. government, too, can file a case against Sai Baba, as many of its citizens, including minors, have been sexually abused. And unless something is done, this is going to continue. Although the crimes are being committed in India, surely there are many means by which the U.S. government can formally ask the Indian government to initiate investigations.

-- Hari Sampath

-- Untouchable? Millions of people worship Sai Baba as God incarnate. More and more say the Indian guru is also a pedophile, by Michelle Goldberg

The above three types of cheats live among people either as householders or renunciates. The next variety of cheats that Sivavakkiyar points out is generally in the garb of sadhus. This group claims that they have consumed kāyakalpa or concoctions that would prolong one’s lifespan. They perform magical feat to everyone everywhere. However, they waste their lives smoking cannabis and consuming opium. In the end, they die lick and salivating like a dog (verse 523).

The fourth category of cheats is those who promise wisdom and liberation. Just as how we have instant coffee and instant tea they promise instant wisdom and instant realization!

The first “instant coffee” is made in Britain in 1771. It was called a “coffee compound” and had a patent granted by the British government. The first American instant coffee was created in 1851. It was used during the Civil War and experimental “cakes” of instant coffee were shared in rations to soldiers. David Strang of Invercargill, New Zealand invented and patented instant or soluble coffee in 1890.

-- Origin and History of Instant Coffee, by History of Coffee

Sivavakkiyar says that they will advertise themselves extensively and usurp others’ property (verse 524). Now-a-days we read about sadhus who offer sakti path and initiation over the internet. Those who go after them are left with nothing but disappointment. The devotees lose their life, their sanity and their wealth.

The last category of cheats is those whom we normally consider as genuine sannyasins. They are not interested in magical shows or other people’s property. They are lazy folks who adorn themselves with ochre robe, rudraksha, and yogic staff. They go around begging for food carrying a water pot. Sivavakkiyar calls them cattle. Instead of seeking Goddess Sakti, they are seeking alms and food from everyone (verse 525).

Sivavakkiyar’s elaborate description of cheats and charlatans makes one wonder whether they were common at him time also!

From the above section one may think that Sivavakkiyar asks people to refrain from supporting the poor and the needy. That is not so. He only warns people to not encourage charlatans. Through three verses (240, 241 and 511) he explains the greatness of food offering and helping others.

Sivavakkiyar says that any amount of wealth, not even great armies, can prevent one from dying. It is only the alms one has offered throughout one’s life that come galloping like a directed horse in the way of one’s death (verse 240). One is reminded of Karna’s story in the Mahabharata, where Lord Krishna seeks the fruits of his alms so that Karna would die in peace. Sivavakkiyar recommends that one should offer sesame seeds, iron, blankets, cotton clothes and food to others (verse 241). He remarks that a place where the citizens have a hand but not the heart of offer things to others is like a void, the most agonizing hell (verse 511).

4. Who is a true yogi, a realized soul?

After elaborating on cheats and charlatans who pose as realized souls Sivavakkiyar explains the state of a true jnāni or a saint.

For a true saint, it does not matter where he is. Whether he is in the forest or in a physical relationship with a woman, it is all the same for him (verse 186). He remains firm like a pot filled with water; there are no fluctuations or vacillations (verse 202) in his mind. Realized beings have tethered their souls so that it does not move around like a kite (203). They remain as pure consciousness. For them, it does not matter whether they are sleeping or remaining awake, whether their senses are kept under control or not. They remain in a thoughtless state, a state of bliss, a state of sat chith ananda (verse 314). Their minds are free from all evil, burnt away by their austerities, like a forest fire (verse 84). Sivavakkiyar remarks with regret that people generally mistake such souls to be mad men (verse 513). The Siddhas also create such an impression intentionally as they do not want to be disturbed by people.

How does one attain the state of a realized soul? One has to first of all realize the impermanence of the body, the ephemeral nature of worldly life, understand the truth about the Divine, the universal conscious being (pati), the limited soul (pasu) and the attachments (pāsam). This is the theoretical aspect of realization while the practical aspect is Siva yoga.

5. Pati, pasu and pāsam:

a. Pati

To explain the esoteric principle of pati, pasu and pāsam, Sivavakkiyar asks a set of questions first. He seeks the answer from realized souls as he feels that experiential knowledge is far superior to textual knowledge.

He asks, “what is mind, what are thoughts, what is Jiva, what is sakti, what is sambhu, what is it that is free from differentiations, what is liberation, what is the origin of everything and what are mantras” (verse 44). In the next verse he provides some answers. He says that the universal conscious being, sivayam is the seed of everything (verse 45). It is beyond a defining character and hence is beyond description (verse 93). It is the state of turiyātītha or the state of consciousness beyond the turiya state the fourth state of consciousness (verse 296). It is like the lightning concealed within the cloud, butter hidden within the milk, oil present within an oil seed and the sight within the eye. It is not limited by a form, a size. It is not the space, not a measurable entity and not a product of transformation. It is not the “other” or the one “without” anything. It is the rarest of the rare, immanent and transcendent entity (verse 73). It is neither good nor bad. It is the middle ground. If one says it is good, it becomes good. If one says it is bad then it becomes so. Sivavakkiyar recommends that we call it good and praise its name (verse 505).