Part 2 of 2

JainismThe Jaina Puranas are like Hindu Puranas encyclopedic epics in style, and are considered as anuyogas (expositions), but they are not considered Jain Agamas and do not have scripture or quasi-canonical status in Jainism tradition.[3] They are best described, states John Cort, as post-scripture literary corpus based upon themes found in Jain scriptures.[3]

Sectarian, pluralistic or monotheistic themeScholars have debated whether the Puranas should be categorized as sectarian, or non-partisan, or monotheistic religious texts.[11][104] Different Puranas describe a number of stories where Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva compete for supremacy.[104] In some Puranas, such as Devi Bhagavata, the Goddess Devi joins the competition and ascends for the position of being Supreme. Further, most Puranas emphasize legends around one who is either Shiva, or Vishnu, or Devi.[11] The texts thus appear to be sectarian. However, states Edwin Bryant, while these legends sometimes appear to be partisan, they are merely acknowledging the obvious question of whether one or the other is more important, more powerful. In the final analysis, all Puranas weave their legends to celebrate pluralism, and accept the other two and all gods in Hindu pantheon as personalized form but equivalent essence of the Ultimate Reality called Brahman.[105][106] The Puranas are not spiritually partisan, states Bryant, but "accept and indeed extol the transcendent and absolute nature of the other, and of the Goddess Devi too".[104]

[The Puranic text] merely affirm that the other deity is to be considered a derivative manifestation of their respective deity, or in the case of Devi, the Shakti, or power of the male divinity. The term monotheism, if applied to the Puranic tradition, needs to be understood in the context of a supreme being, whether understood as Vishnu, Shiva or Devi, who can manifest himself or herself as other supreme beings.

— Edwin Bryant, Krishna: The Beautiful Legend of God: Srimad Bhagavata Purana[104]

Ludo Rocher, in his review of Puranas as sectarian texts, states, "even though the Puranas contain sectarian materials, their sectarianism should not be interpreted as exclusivism in favor of one god to the detriment of all others".[107]

Puranas as historical textsDespite the diversity and wealth of manuscripts from ancient and medieval India that have survived into the modern times, there is a paucity of historical data in them.[35] Neither the author name nor the year of their composition were recorded or preserved, over the centuries, as the documents were copied from one generation to another. This paucity tempted 19th-century scholars to use the Puranas as a source of chronological and historical information about India or Hinduism.[35] This effort was, after some effort, either summarily rejected by some scholars, or become controversial, because the Puranas include fables and fiction, and the information within and across the Puranas was found to be inconsistent.[35]

In early 20th-century, some regional records were found to be more consistent, such as for the Hindu dynasties in Telangana, Andhra Pradesh. Basham, as well as Kosambi, have questioned whether lack of inconsistency is sufficient proof of reliability and historicity.[35] More recent scholarship has attempted to, with limited success, states Ludo Rocher, use the Puranas for historical information in combination with independent corroborating evidence, such as "epigraphy, archaeology, Buddhist literature, Jaina literature, non-Puranic literature, Islamic records, and records preserved outside India by travelers to or from India in medieval times such as in China, Myanmar and Indonesia".[108][109]

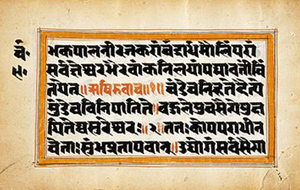

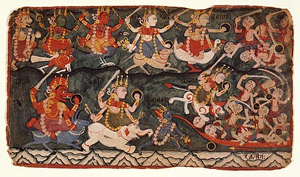

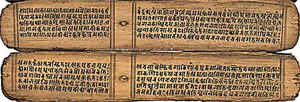

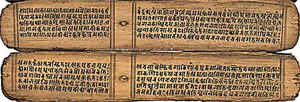

Manuscripts An 11th-century Nepalese palm-leaf manuscript in Sanskrit of Devimahatmya (Markandeya Purana).

An 11th-century Nepalese palm-leaf manuscript in Sanskrit of Devimahatmya (Markandeya Purana).The study of Puranas manuscripts has been challenging because they are highly inconsistent.[110][111] This is true for all Mahapuranas and Upapuranas.[110] Most editions of Puranas, in use particularly by Western scholars, are "based on one manuscript or on a few manuscripts selected at random", even though divergent manuscripts with the same title exist. Scholars have long acknowledged the existence of Purana manuscripts that "seem to differ much from printed edition", and it is unclear which one is accurate, and whether conclusions drawn from the randomly or cherrypicked printed version were universal over geography or time.[110] This problem is most severe with Purana manuscripts of the same title, but in regional languages such as Tamil, Telugu, Bengali and others which have largely been ignored.[110]

Modern scholarship noticed all these facts. It recognized that the extent of the genuine Agni Purana was not the same at all times and in all places, and that it varied with the difference in time and locality. (...) This shows that the text of the Devi Purana was not the same everywhere but differed considerably in different provinces. Yet, one failed to draw the logical conclusion: besides the version or versions of Puranas that appear in our [surviving] manuscripts, and fewer still in our [printed] editions, there have been numerous other versions, under the same titles, but which either have remained unnoticed or have been irreparably lost.

— Ludo Rocher, The Puranas[58][112]

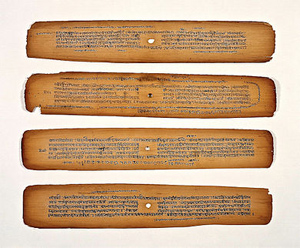

ChronologyNewly discovered Puranas manuscripts from the medieval centuries has attracted scholarly attention and the conclusion that the Puranic literature has gone through slow redaction and text corruption over time, as well as sudden deletion of numerous chapters and its replacement with new content to an extent that the currently circulating Puranas are entirely different from those that existed before 11th century, or 16th century.[113]

For example, a newly discovered palm-leaf manuscript of Skanda Purana in Nepal has been dated to be from 810 CE, but is entirely different from versions of Skanda Purana that have been circulating in South Asia since the colonial era.[69][113] Further discoveries of four more manuscripts, each different, suggest that document has gone through major redactions twice, first likely before the 12th century, and the second very large change sometime in the 15th-16th century for unknown reasons.[114] The different versions of manuscripts of Skanda Purana suggest that "minor" redactions, interpolations and corruption of the ideas in the text over time.[114]

Rocher states that the date of the composition of each Purana remains a contested issue.[115][116] Dimmitt and van Buitenen state that each of the Puranas manuscripts is encyclopedic in style, and it is difficult to ascertain when, where, why and by whom these were written:[117]As they exist today, the Puranas are a stratified literature. Each titled work consists of material that has grown by numerous accretions in successive historical eras. Thus no Purana has a single date of composition. (...) It is as if they were libraries to which new volumes have been continuously added, not necessarily at the end of the shelf, but randomly.

— Cornelia Dimmitt and J.A.B. van Buitenen, Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas[117]

ForgeriesMany of the extant manuscripts were written on palm leaf or copied during the British India colonial era, some in the 19th century.[118][119] The scholarship on various Puranas, has suffered from frequent forgeries, states Ludo Rocher, where liberties in the transmission of Puranas were normal and those who copied older manuscripts replaced words or added new content to fit the theory that the colonial scholars were keen on publishing.[118][119]TranslationsHorace Hayman Wilson published one of the earliest English translations of one version of the Vishnu Purana in 1840.[120] The same manuscript, and Wilson's translation, was reinterpreted by Manmatha Nath Dutt, and published in 1896.[121] The All India Kashiraj Trust has published editions of the Puranas.[122]

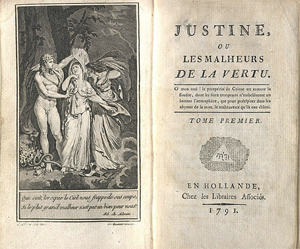

Maridas Poullé (Mariyadas Pillai) published a French translation from a Tamil version of the Bhagavata Purana in 1788, and this was widely distributed in Europe becoming an introduction to the 18th-century Hindu culture and Hinduism to many Europeans during the colonial era. Poullé republished a different translation of the same text as Le Bhagavata in 1795, from Pondicherry.[123] A copy of Poullé translation is preserved in Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

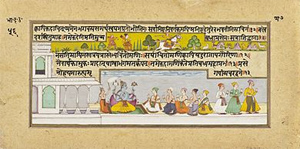

Influence The Puranas have had a large cultural impact on Hindus, from festivals to diverse arts. Bharata natyam (above) is inspired in part by Bhagavata Purana.[124]

The Puranas have had a large cultural impact on Hindus, from festivals to diverse arts. Bharata natyam (above) is inspired in part by Bhagavata Purana.[124]The most significant influence of the Puranas genre of Indian literature have been state scholars and particularly Indian scholars,[125] in "culture synthesis", in weaving and integrating the diverse beliefs from ritualistic rites of passage to Vedantic philosophy, from fictional legends to factual history, from individual introspective yoga to social celebratory festivals, from temples to pilgrimage, from one god to another, from goddesses to tantra, from the old to the new.[126] These have been dynamic open texts, composed socially, over time. This, states Greg Bailey, may have allowed the Hindu culture to "preserve the old while constantly coming to terms with the new", and "if they are anything, they are records of cultural adaptation and transformation" over the last 2,000 years.[125]

The Puranic literature, suggests Khanna, influenced "acculturation and accommodation" of a diversity of people, with different languages and from different economic classes, across different kingdoms and traditions, catalyzing the syncretic "cultural mosaic of Hinduism".[127] They helped influence cultural pluralism in India, and are a literary record thereof.[127]

Om Prakash states the Puranas served as efficient medium for cultural exchange and popular education in ancient and medieval India.[128] These texts adopted, explained and integrated regional deities such as Pashupata in Vayu Purana, Sattva in Vishnu Purana, Dattatreya in Markendeya Purana, Bhojakas in Bhavishya Purana.[128] Further, states Prakash, they dedicated chapters to "secular subjects such as poetics, dramaturgy, grammar, lexicography, astronomy, war, politics, architecture, geography and medicine as in Agni Purana, perfumery and lapidary arts in Garuda Purana, painting, sculpture and other arts in Vishnudharmottara Purana".[128]

Indian ArtsThe cultural influence of the Puranas extended to Indian classical arts, such as songs, dance culture such as Bharata Natyam in south India[124] and Rasa Lila in northeast India,[129] plays and recitations.[130]

FestivalsThe myths, lunar calendar schedule, rituals and celebrations of major Hindu cultural festivities such as Holi, Diwali and Durga Puja are in the Puranic literature.[131][132]

Notes1. Six disciples: Sumati, Agnivarchaha, Mitrayu, Shamshapyana, Akritaverna and Savarni

2. The early Buddhist text (Sutta Nipata 3.7 describes the meeting between the Buddha and Sela. It has been translated by Mills and Sujato as, "(...) the brahmin Sela was visiting Āpaṇa. He was an expert in the three Vedas, with the etymologies, the rituals, the phonology and word analysis, and fifthly the legendary histories".[24]

3. This text underwent a near complete rewrite in or after 15th/16th century CE, and almost all extant manuscripts are Vaishnava (Krishna) bhakti oriented.[53]

4. Like all Puranas, this text underwent extensive revisions and rewrite in its history; the extant manuscripts are predominantly an encyclopedia, and so secular in its discussions of gods and goddesses that scholars have classified as Smartism, Shaktism, Vaishnavism and Shaivism Purana.[54]

5. This text is named after a Vishnu avatar, but extant manuscripts praise all gods and goddesses equally with some versions focusing more on Shiva.[55]

6. Hazra includes this in Vaishnava category.[46]

7. This text includes the famous Devi-Mahatmya, one of the most important Goddess-related text of the Shaktism tradition in Hinduism.[56]

8. There are only four Vedas in Hinduism. Several texts have been claimed to have the status of the Fifth Veda in the Hindu tradition. For example, the Natya Shastra, a Sanskrit text on the performing arts, is also so claimed.[92]

References

Citations1. Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, ISBN 0-877790426, page 915

2. Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415172813, pages 437-439

3. John Cort (1993), Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts (Editor: Wendy Doniger), State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791413821, pages 185-204

4. Gregory Bailey (2003), The Study of Hinduism (Editor: Arvind Sharma), The University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 978-1570034497, page 139

5. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, p.16, 12-21

6. Nair, Shantha N. (2008). Echoes of Ancient Indian Wisdom: The Universal Hindu Vision and Its Edifice. Hindology Books. p. 266. ISBN 978-81-223-1020-7.

7. Cornelia Dimmitt (2015), Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas, Temple University Press, ISBN 978-8120839724, page xii, 4

8. Collins, Charles Dillard (1988). The Iconography and Ritual of Śiva at Elephanta. SUNY Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-88706-773-0.

9. Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415172813, page 503

10. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 12-13, 134-156, 203-210

11. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 21-24, 104-113, 115-126

12. Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520207783, page xxxix

13. Thompson, Richard L. (2007). The Cosmology of the Bhagavata Purana 'Mysteries of the Sacred Universe. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-208-1919-1.

14. Dominic Goodall (1996), Hindu Scriptures, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520207783, page xli

15. BN Krishnamurti Sharma (2008), A History of the Dvaita School of Vedānta and Its Literature, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120815759, pages 128-131

16. Douglas Harper (2015), Purana, Etymology Dictionary

17. Ludo Rocher (1986). The Purāṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5.

18. Thomas B. Coburn (1988). Devī-Māhātmya: The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 23–27. ISBN 978-81-208-0557-6.

19. P. V. Kane. History of Dharmasastra (Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil Law in India), Vol.5.2, 1st edition, 1962. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. pp. 816–821.

20. Kane, P. V. "History of Dharmasastra (Ancient and mediaeval Religious and Civil Law), v.5.2, 1st edition, 1962 : P. V. Kane". p. 816.

21. P. V. Kane. History of Dharmasastra (Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil Law in India), Vol.5.2, 1st edition, 1962. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. pp. 816–817.

22. Patrick Olivelle (1998). The Early Upanishads: Annotated Text and Translation. Oxford University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-19-535242-9.

23. Thomas Colburn (2002), Devī-māhātmya: The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805576, page 24-25

24. Sutta Nipata 3.7, To Sela and his Praise of the Buddha, Laurence Mills and Bhikkhu Sujato

25. Brhadaranyaka Upanisad 2.4.10, 4.1.2, 4.5.11. Satapatha Brahmana (SBE, Vol. 44, pp. 98, 369). Moghe 1997, pp. 160,249

26. Dimmitt & van Buitenen 2012, p. 7.

27. Dimmitt & van Buitenen 2012, pp. 7-8, context: 4-13.

28. Klaus K. Klostermaier (5 July 2007). A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition. SUNY Press. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4.

29. Johnson 2009, p. 247

30. Pargiter 1962, pp. 30–54.

31. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 154-156

32. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 209-215

33. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 59-61

34. Klaus Klostermaier (2007), A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791470824, pages 281-283 with footnotes on page 553

35. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 115-121 with footnotes

36. Lochtefeld, James G. (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z, The Rosen Publishing Group, p. 760, ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4

37. Monier-Williams 1899, p. 752, column 3, under the entry Bhagavata.

38. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 139-149

39. Hardy 2001

40. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 202-203

41. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 70-71

42. RC Hazra (1987), Studies in the Puranic Records on Hindu Rites and Customs, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120804227, pages 8-11

43. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 134-137

44. John Dowson (2000). A Classical Dictionary of Hindu Mythology and Religion, Geography, History and Literature. Psychology Press. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-0-415-24521-0.

45. Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5.

46. RC Hazra (1940), Studies in the Puranic Records on Hindu Rites and Customs, Motilal Banarsidass (1987 Reprint), ISBN 978-8120804227, pages 96-97

47. Wilson, Horace H. (1864), The Vishṅu Purāṅa: a system of Hindu mythology and tradition Volume 1 of 4, Trübner, p. LXXI

48. Doniger 1993, pp. 59–83

49. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, page 78-79

50. Catherine Ludvik (2007), Sarasvatī, Riverine Goddess of Knowledge, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004158146, pages 139-141

51. MN Dutt, The Garuda Purana Calcutta (1908)

52. H Hinzler (1993), Balinese palm-leaf manuscripts Archived 1 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Landen Volkenkunde, Manuscripts of Indonesia 149 (1993), No 3, Leiden: BRILL, page 442

53. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 161-164

54. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 20-22, 134-137

55. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 35, 185, 199, 239-242

56. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 191-192

57. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 113-114, 153-154, 161, 167-169, 171-174, 182-187, 190-194, 210, 225-227, 242

58. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, page 63

59. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, page 68

60. R. C. Hazra, Studies in the Upapuranas, vol. I, Calcutta, Sanskrit College, 1958. Studies in the Upapuranas, vol. II, Calcutta, Sanskrit College, 1979. Studies in Puranic Records on Hindu Rites and Customs, Delhi, Banarsidass, 1975. Ludo Rocher, The Puranas – A History of Indian Literature Vol. II, fasc. 3, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1986.

61. Verbal Narratives: Performance and Gender of the Padma Purana, by T.N. Sankaranarayana in Kaushal 2001, pp. 225–234

62. Thapan 1997, p. 304

63. "Purana at Gurjari". Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

64. Shulman 1980

65. Stephen Knapp (2005), The Heart of Hinduism, ISBN 978-0595350759, pages 44-45

66. Yves Bonnefoy and Wendy Doniger (1993), Asian Mythologies, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226064567, pages 92-95

67. Gregor Maehle (2009), Ashtanga Yoga, New World, ISBN 978-1577316695, page 17

68. Skanda Purana Shankara Samhita Part 1, Verses 1.8.20-21 (Sanskrit)

69. R Andriaensen et al (1994), Towards a critical edition of the Skandapurana, Indo-Iranian Journal, Vol. 37, pages 325-331

70. Matsya Purana 53.65

71. Rao 1993, pp. 85–100

72. Johnson 2009, p. 248

73. Jonathan Edelmann (2013), The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition (Editors: Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey), Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149983, pages 48-62

74. Vayu Purana 1. 31-2.

75. RC Hazra (1987), Studies in the Puranic Records on Hindu Rites and Customs, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120804227, page 4

76. Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415172813, pages 440-443

77. Gopal Gupta (2013), The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition (Editors: Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey), Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149983, pages 63-75

78. Graham Schweig (2013), The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition (Editors: Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey), Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149983, pages 117-132

79. Flood 1996, pp. 104-110.

80. Flood 1996, pp. 109–112

81. Yves Bonnefoy and Wendy Doniger (1993), Asian Mythologies, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226064567, pages 38-39

82. Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey (2013), The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149983, pages 130-132

83. Vishnu Purana Chapter 7

84. Sara Schastok (1997), The Śāmalājī Sculptures and 6th Century Art in Western India, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004069411, pages 77-79, 88

85. Edwin Bryant (2007), Krishna : A Sourcebook: A Sourcebook, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195148923, pages 111-119

86. Patton, Laurie L.(1994), Authority, Anxiety, and Canon: Essays in Vedic Interpretation SUNY Series in Hindu Studies, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0585044675, p. 98

87. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 13-16

88. Rocher 1986, pp. 14-15 with footnotes.

89. Barbara Holdrege (1995), Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791416402, pages 95-97

90. Rocher 1986, pp. 15 with footnotes.

91. Barbara Holdrege (2012). Hananya Goodman (ed.). Between Jerusalem and Benares: Comparative Studies in Judaism and Hinduism. State University of New York Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4384-0437-0.

92. D. Lawrence Kincaid (2013). Communication Theory: Eastern and Western Perspectives. Elsevier. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4832-8875-8.

93. Kee Bolle (1963), Reflections on a Puranic Passage, History of Religions, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Winter, 1963), pages 286-291

94. Ariel Glucklich 2008, p. 146, Quote: The earliest promotional works aimed at tourists from that era were called mahatmyas.

95. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 1-5, 12-21, 79-80, 96-98; Quote: These are the true encyclopedic Puranas. in which detached chapters or sections, dealing with any imaginable subject, follow one another, without connection or transition. Three Puranas especially belong to this category: Matsya, Garuda and above all Agni.

96. Ronald Inden (2000), Querying the Medieval : Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124309, pages 94-95

97. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 78-79

98. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 104-106 with footnotes

99. Urs App (2010), The Birth of Orientalism, University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0812242614, pages 331, 323-334

100. Jan Gonda (1975), Selected Studies: Indo-European linguistics, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004042285, pages 51-86

101. Ronald Inden (2000), Querying the Medieval : Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124309, pages 87-98

102. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 19-20

103. Ronald Inden (2000), Querying the Medieval : Texts and the History of Practices in South Asia, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195124309, pages 95-96

104. Edwin Bryant (2003), Krishna: The Beautiful Legend of God: Srimad Bhagavata Purana, Penguin, ISBN 978-0141913377, pages 10-12

105. EO James (1997), The Tree of Life, BRILL Academic, ISBN 978-9004016125, pages 150-153

106. Barbara Holdrege (2015), Bhakti and Embodiment, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415670708, pages 113-114

107. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, page 23 with footnote 35

108. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 121-127 with footnotes

109. L Srinivasan (2000), Historicity of the Indian mythology : Some observations, Man in India, Vol. 80, No. 1-2, pages 89-106

110. Ludo Rocher (1986), The Puranas, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447025225, pages 59-67

111. Gregory Bailey (2003), The Study of Hinduism (Editor: Arvind Sharma), The University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 978-1570034497, pages 141-142

112. Rajendra Hazra (1956), Discovery of the genuine Agneya-purana, Journal of the Oriental Institute Baroda, Vol. 4-5, pages 411-416

113. Dominic Goodall (2009), Parākhyatantram, Vol 98, Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie, ISBN 978-2855396422, pages xvi-xvii

114. Kengo Harimoto (2004), in Origin and Growth of the Purāṇic Text Corpus (Editor: Hans Bakker), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120820494, pages 41-64

115. Rocher 1986, p. 249.

116. Gregory Bailey 2003, pp. 139-141, 154-156.

117. Dimmitt & van Buitenen 2012, p. 5.

118. Rocher 1986, pp. 49-53.

119. Avril Ann Powell (2010). Scottish Orientalists and India: The Muir Brothers, Religion, Education and Empire. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 130, 128–134, 87–90. ISBN 978-1-84383-579-0.

120. HH Wilson (1840), Vishnu Purana Trubner and Co., Reprinted in 1864

121. MN Dutt (1896), Vishnupurana Eylsium Press, Calcutta

122. Mittal 2004, p. 657

123. Jean Filliozat (1968), Tamil Studies in French Indology, in Tamil Studies Abroad, Xavier S Thani Nayagam, pages 1-14

124. Katherine Zubko (2013), The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition (Editors: Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey), Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149983, pages 181-201

125. Greg Bailey (2001), Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (Editor: Oliver Leaman), Routledge, ISBN 978-0415172813, pages 442-443

126. Gregory Bailey (2003), The Study of Hinduism (Editor: Arvind Sharma), The University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 978-1570034497, pages 162-167

127. R Champakalakshmi (2012), Cultural History of Medieval India (Editor: M Khanna), Berghahn, ISBN 978-8187358305, pages 48-50

128. Om Prakash (2004), Cultural History of India, New Age, ISBN 978-8122415872, pages 33-34

129. Guy Beck (2013), The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition (Editors: Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey), Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149983, pages 181-201

130. Ilona Wilczewska (2013), The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition (Editors: Ravi Gupta and Kenneth Valpey), Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149983, pages 202-220

131. A Whitney Sanford (2006), Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity (Editor: Guy Beck), State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791464168, pages 91-94

132. Tracy Pintchman (2005), Guests at God's Wedding: Celebrating Kartik among the Women of Benares, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791465950, pages 60-63, with notes on 210-211

Cited sources• Bailey, Gregory (2003). "The Puranas". In Sharma, Arvind (ed.). The Study of Hinduism. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-449-7.

• Dimmitt, Cornelia; van Buitenen, J. A. B. (2012) [1977]. Classical Hindu Mythology: A Reader in the Sanskrit Puranas. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-4399-0464-0.

• Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1993). Purāṇa Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. Albany, NY: State University of New York. ISBN 0-7914-1382-9.

• Hardy, Friedhelm (2001). Viraha-Bhakti – The Early History of Krsna Devotion in South India. ISBN 0-19-564916-8.

• Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43304-5.

• Johnson, W.J. (2009). A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861025-0.

• Kaushal, Molly, ed. (2001). Chanted Narratives – The Katha Vachana Tradition. ISBN 81-246-0182-8.

• Glucklich, Ariel (2008). The Strides of Vishnu : Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2.

• Mackenzie, C Brown (1990). The Triumph of the Goddess – The Canonical Models and Theological Visions of the DevI-BhAgavata PuraNa. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-0363-7.

• Mittal, Sushil (2004). The Hindu World. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21527-5.

• Moghe, S. G., ed. (1997). Professor Kane's contribution to Dharmasastra literature. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld (P) Ltd. ISBN 81-246-0075-9.

• Monier-Williams, Monier (1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

• Pargiter, F. E. (1962) [1922]. Ancient Indian historical tradition. Original publisher Oxford University Press, London. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass. OCLC 1068416.

• Rao, Velcheru Narayana (1993). "Purana as Brahminic Ideology". In Doniger Wendy (ed.). Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1381-0.

• Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5.

• Shulman, David Dean (1980). Tamil Temple Myths: Sacrifice and Divine Marriage in the South Indian Saiva Tradition. ISBN 0-691-06415-6.

• Singh, Nagendra Kumar (1997). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism. ISBN 81-7488-168-9.

• Thapan, Anita Raina (1997). Understanding Gaṇapati: Insights into the Dynamics of a Cult. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers. ISBN 81-7304-195-4.

External links• GRETIL (uni-goettingen.de)

Translations[edit]

• Agni Purana (in English), Volume 2, MN Dutt (Translator), Hathi Trust Archives

• Vishnu Purana H.H. Wilson

• Vishnu Purana, MN Dutt

• Brahmanda Purana, GV Tagare

Narsingh Purana