by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/2/21

-- Liber LII, Manifesto of the O.T.O., by Aleister Crowley

-- Magick in Theory and Practice, by Aleister Crowley

-- Magick Without Tears, by Aleister Crowley

-- Moonchild, by Aleister Crowley

-- The Book of Lies, by Aleister Crowley

-- The Book of the Law, by Aleister Crowley

-- The Diary of a Drug Fiend, by Aleister Crowley

-- The Heart of the Master, by Aleister Crowley

-- The Vindication of Nietzsche, by Aleister Crowley

-- Aleister Crowley and Coprophagy: The Limits of Transgression, by Georgia van Raalte

-- Aleister Crowley as Political Theorist, by Kerry Bolton

-- Ordo Templi Orientis Spermo-Gnosis: Carl Kellner, Theodor Reuss, Aleister Crowley, by P.R. Koenig

-- The OTO & the CIA -- Ordis Templis Intelligentis, by Alex Constantine

-- Ordo Templi Orientis Spermo-Gnosis: Carl Kellner, Theodor Reuss, Aleister Crowley, by P.R. Koenig

-- 13th Degree: Royal Arch of Enoch (or Knights of the Ninth Arch), by Charles T. McClenechan

Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica, by Wikipedia

-- Knights Hospitaller, by Wikipedia

-- Nosferatu's Baby (Much Too Much) Too hot To Handle, by Peter-R. Koenig

-- Ordo Templi Orientis Outer Head of the Order?, by Karl Germer

-- The Templar's Reich Milieu: The Slaves Shall Serve, by Peter-Robert Koenig

-- Theodor Reuss: The Programme of Construction and the Guiding Principles of the Gnostic Neo-Christians O.T.O., published in 1920, by P.R. Koenig

-- A Note on Gerard Aumont, by Ordo Templi Orientis International Headquarters

-- The Scented Garden of Abdullah the Satirist of Shiraz, by Ordo Templi Orientis

-- Ananda Metteyya [Charles Henry Allan Bennett]: The First British Emissary of Buddhism [Excerpt], by Elizabeth J. Harris

-- Honour Thy Fathers: A Tribute to the Venerable Kapilavaddho ... And brief History of the Development of Theravāda Buddhism in the UK, by Terry Shine

-- Convert to Compassion: Allan Bennett, from Theravada Buddhism and the British Encounter: Religious, Missionary and Colonial Experience in Nineteenth Century Sri Lanka [Excerpt], by Elizabeth J. Harris

-- Charles Henry Allan Bennett, by Wikipedia

-- Allan Bennett, by AstrumArgenteum.org

--Allan Bennett, by George Knowles

-- Tibet House US: Overview, by Tibet House US

-- Tibet Society: Our Story, by tibetsociety.com

-- Tibetan Friendship Group, by tibet.org

-- Tibet, the ‘great game’ and the CIA, by Richard M. Bennett

-- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about Parapsychology, DRAFT 3, by cia.gov

-- Committee for a Free Asia, by Central Intelligence Agency

-- The Dalai Lama, by The Central Intelligence Agency

-- The Indian Communist Party and the Sino-Soviet Dispute, by Office of Current Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency

-- The Sino-Indian Border Dispute, by Central Intelligence Agency

-- Communist Party Weekly, Vol. X, No. 44, New Delhi, November 4, 1962, Approved for Release: 8/27/2000: CIA-RDP78-03061A000100070014-0, by Central Intelligence Agency

-- Nehru on Communism: An Awakening, by cia.gov

-- Scientology Guardian's Office Debbie Sharp Reveals Secret CIA Human Experiments

-- Sex, Drugs and the CIA, by Douglas Valentine

-- The CIA's Secret War in Tibet, by Kenneth Conboy and James Morrison

-- Project MKULtra, by Wikipedia

The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor was an initiatic occult organisation that first became public in late 1894, although according to an official document of the order[1] it began its work in 1870. According to this document, authored by Peter Davidson, the order was established by Max Theon, who when in England was initiated as a Neophyte by "an adept of the serene, ever-existing and ancient Order of the original H. B. of L."[2]

The Order's relation, if any, with the mysterious "Brotherhood of Luxor" that Helena Blavatsky spoke of is not clear.[3]

Theon thus became Grand Master of the Exterior Circle of the Order. However, apart from his initiatory role, he seems to have little to do with the day to day running of the order, or of its teachings. He seems to have left these things to Peter Davidson, who was the Provincial Grand Master of the North (Scotland), and later also the Eastern Section (America).

Peter Davidson, cofounder of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Light (HBL), a nineteenth-century British occult order, was born and raised in Forres, Scotland. In 1866 he married Christina Ross. He became a violin maker and in 1871 published a book, The Violin, that surveyed the historical and technical aspects of the instrument.

Violin

-- Davidson, Peter (1842-1929), by Encyclopedia.com

The order's teachings drew heavily from the magico-sexual theories of Paschal Beverly Randolph, who influenced groups such as the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.) (later headed by Aleister Crowley) (Greenfield 1997) although it is not clear whether or not Randolph himself was actually a part of the Order.[4]

Prior to the rise of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in 1888 the HBoL was the only order that taught practical occultism in the Western Mystery Tradition. Among its members were a number of occultists, spiritualists, and Theosophists. Initial relations between the Order and the Theosophical Society were cordial, with most members of the order also prominent members of the T.S.[5]

Later there was a falling out, as the Order was opposed to the eastern-based teachings of the later Blavatsky (Davidson considered that Blavatsky had fallen under the influence of "a greatly inferior Order, belonging to the Buddhist [sic] Cult"). Conversely, the conviction in 1883 of the Secretary of the Order, Thomas Henry Burgoyne for fraud, was claimed by the Theosophists to show the immorality of the Order.

Thomas H. Burgoyne [Thomas Dalton]

Unlike the case of Peter Davidson, there are no descendants or local historians anxious to bear witness to the virtues and achievements of Thomas Henry Dalton (1855?-1895? [Date of birth deduced from prison records; death record searched for, without success, by Mr. Deveney.]), better known as T.H. Burgoyne, whose misdemeanors are amply chronicled in the Theosophical literature [B.6]. The “Church of Light,” a still active Californian group which descended from Burgoyne’s teachings, disposes of his life up to 1886 as follows:T.H. Burgoyne was the son of a physician in Scotland. He roamed the moors during his boyhood and became conversant with the birds and flowers. He was an amateur naturalist. He also was a natural seer. Through his seership he contacted The Brotherhood of Light on the inner plane, and later contacted M. Theon in person. Still later he came to America, where he taught and wrote on occult subjects. [“The Founders of the Church of Light.”]

While this romanticized view cannot entirely be trusted, there is no doubt that Burgoyne was a medium and that he was developed as such by Max Theon. Burgoyne told Gorham Blake that he “visited [Theon’s] house as a student every day for a long time” [B.8.k], and gave this clue to their relationship in The Light of Egypt:… those who are psychic, may not know WHEN the birth of an event will occur, but they Feel that it will, hence prophecy.

The primal foundation of all thought is right here, for instance, M. Theon may wish a certain result; if I am receptive, the idea may become incarnated in me, and under an extra spiritual stimulus it may grow and mature and become a material fact.

Burgoyne was making enquiries in occult circles by 1881, when he wrote to [The Rev W. A.] Ayton asking to visit him for a discussion of occultism. The clergyman was shocked when he met this “Dalton,” who (Ayton says) boasted of doing Black Magic [B.6.f], and forthwith sent him packing [B.6.k]. Later Ayton would be appalled to learn that it was this same young man with whom, as “Burgoyne,” he had been corresponding on H.B. of L. business. Having decided that the mysterious Grand Master “Theon” was really Hurrychund Chintamon, Ayton deduced that the young Scotsman must have learned his black magic from this Indian adventurer.

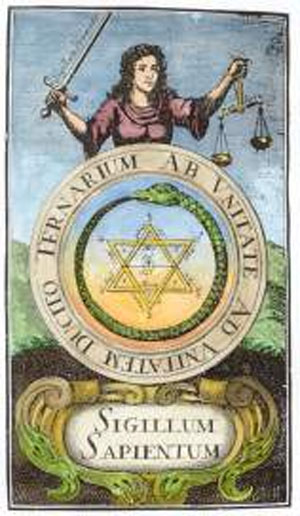

This lovely picture raises as many questions as it answers. Adam McLean tells me in a private e-mail (3-18-08) that the book Philalethes Illustratus is about alchemy. He adds:The ouroboros is a well know symbol in alchemy, as is the interwoven triangles. These were often brought together in alchemical emblems. There was a particular focus on this image in the early 18th century, through its use as an illustration in the influential 'Golden Chain of Homer', written or edited by Anton Josef Kirchweger, first issued at Frankfurt and Leipzig in four German editions in 1723, 1728, 1738 and 1757. A Latin version was issued at Frankfurt in 1762, and further German editions followed. In the late eighteenth century Sigismund Bacstrom made a rather poor translation of the work into English. Blavatsky was very interested in this work and apparently wanted to write a commentary on it. Part of this was published in the Theosophical Society Journal 'Lucifer' in 1891. The Rev W. A. Ayton, the alchemical enthusiast, and contact of Blavatsky, used a variation of this image as a letterhead on his papers.

This is a copy of the letterhead of Rev W. A. Ayton which Adam McLean sent me. Ayton is mentioned in Blavatsky's diary in 1878 and 1879 (BCW I, p 410, 421 and II, p. 42). Note that where Blavatsky's seal has astrological connotations with for instance the sign of the Leo in the right-bottom corner, Ayton has an actual lion in exactly the same spot as well as a sun and moon. Adam McLean notes (3-18-08) that Ayton was a member of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor and his seal is similar to theirs.

It's clear at this point that the Theosophical Seal has a western esoteric background. Seen through the Eliphas Levi seal the cross was turned into an Egyptian cross, which makes sense as an Egyptian source for the early theosophical adepts was hinted at in their name: the Brotherhood of Luxor (whether a connection with the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor should be assumed is an open question of theosophical history).

The circle on top with the swastika inside is present in Blavatsky’s seal. I have not been able to find any precursors to that. In this respect Blavatsky’s seal was clearly the example for the Theosophical Seal.

-- Early history of the Theosophical Seal, by Katinka Hesselink 2006, 2008

Hurrychund Chintamon had played an important part in the early Theosophical Society and in the move of Blavatsky and Olcott from New York to India. He had been their chief Indian correspondent during 1877-1878, when he was President of the Bombay Arya Samaj (a Vedic revival movement with which the early Theosophical Society was allied). After Blavatsky and Olcott arrived in Bombay in 1879 and met Chintamon in person, they discovered that he was a scoundrel and an embezzler, and expelled him from the Society. Chintamon came to England in 1879 or 1880, and stayed until 1883, when he returned to make further trouble for the Theosophists in India. Perhaps the fact that Chintamon was in England when Burgoyne first met Theon led some to conclude that they were the same person. But this cannot be the whole story. Ayton claimed very clearly and repeatedly that he had proof of Burgoyne’s being in company with Chintamon. In a letter in the private collection, Ayton writes:I have since discovered that Hurrychund Chintaman the notorious Black Magician was in company with Dalton at Bradford. By means of a Photograph I have traced him to Glasgow & even to Banchory, under the alias of Darushah Chichgur. Friends in London saw him there just before his return to India. This time coincides with that when I noticed a great change in the management. Chintaman had supplied the Oriental knowledge as he was a Sanskrit scholar & knew much. Theon was Chintaman! Friends have lately seen him in India where he is still at his tricks.

Before her disillusion[ment] with Chintamon, Blavatsky had touted him to the London Theosophists as a “great adept.” After the break that followed on her meeting with him in person, Chintamon allied himself to the rising Western opposition to esoteric Buddhism exemplified by Stainton Moses, C.C. Massey, William Oxley, Emma Hardinge Britten, Thomas Lake Harris, and others. From this formidable group, Burgoyne first contracted the hostility towards Blavatsky’s enterprise that would mark all his writings.

Chintamon also appears in connection with “H.B. Corinni,” the otherwise unidentifiable (and variously spelled) “Private Secretary” of Theon, who was thought by the police to be just another of Burgoyne’s aliases. Ayton, however, believed Corinni to be Chintamon’s son, who he said offered Blavatsky’s old letters for sale to the President of the London Branch of the Theosophical Society, Charles Carleton Massey. [Ayton to unnamed American neophyte, 11 June 1886, based on what he had been told by Massey.] The flaw in Ayton’s thesis is of course the existence of a real and independent Max Theon, of whom we, unlike Ayton, have documentary evidence. Nonetheless, after more than a hundred years, the whole tangle of misidentifications involving Chintamon, “Christamon,” and “Metamon” [see B.9.c-3] with the Order cannot be entirely resolved.

By October 1882, Burgoyne was in Leeds, working in the menial trade of a grocer. [This is the trade ascribed to him in the court records. The records of the Leeds Constabulary call him “medium and astrologer.”] Here he tried to bring off an advertising fraud [B.6.d] so timid as to cast serious doubt on his abilities as a black magician! As a consequence, he spent the first seven months of 1883 in jail. He had probably met Theon before his incarceration, and, as we have seen, worked for a time in daily sessions as Theon’s medium. On his release he struck up or resumed relations with Peter Davidson, and became the Private Secretary to the Council of the H.B. of L. when it went public the following year.

Burgoyne contributed many letters and articles to The Occult Magazine, usually writing under the pseudonym “Zanoni.” He also contributed to Thomas Johnson’s Platonist [see B.7.c], showing considerably more literacy than in the letter that so amused the Theosophists [B.7.b]. But he never claimed to be an original writer. In the introduction to the “Mysteries of Eros” [A.3.b] he states his role as that of amanuensis and compiler. The former term reveals what the H.B. of L. regarded as the true source of its teachings – the initiates of the Interior Circle of the Order. The goal of the magical practice taught by the H.B. of L. was the development of the potentialities of the individual so that he or she could communicate directly with the Interior Circle and with the other entities, disembodied and never embodied, that the H.B. of L. believed to populate the universes. If Gorham Blake is to be credited [B.6.k], Davidson and Burgoyne “confessed” to him that Burgoyne was an “inspirational medium” and that the teachings of the Order came through his mediumship. Stripped of the bias inherent in the terms “medium,” and “confess,” there is no reason to doubt the statement of Burgoyne’s role. In the Order’s own terminology, however, his connection with the spiritual hierarchies of the universe was through “Blending” – the taking over of the conscious subject’s mind by the Initiates of the Interior Circle and the Potencies, Powers, and Intelligences of the celestial hierarchies – and through the “Sacred Sleep of Sialam” (see Section 15, below).

Shortly after arriving in Georgia, for all the Theosophists’ efforts to intercept him [B.6.1], Burgoyne parted with Davidson. From then on, the two communicated mainly through their mutual disciples, squabbling over fees for reading the neophytes’ horoscopes and over Burgoyne’s distribution of the Order’s manuscripts, with each man essentially running a separate organization. This split may be reflected in the French version of “Laws of Magic Mirrors” [A.3.a], which was prepared in 1888 and which bears the reference “Peter Davidson, Provincial Grand Mater of the Eastern Section.”

Burgoyne made his way from Georgia first to Kansas, then to Denver, and finally to Monterey, California, staying with H.B. of L. members as he went. According to the Church of Light, Burgoyne now met Normal Astley, a professional surveyor and retired Captain in the British Army. After 1887 Astley and a small group of students engaged Burgoyne to write the basic H.B. of L. teachings as a series of lessons, giving him hospitality and a small stipend. Astley is actually said to have visited England to meet Theon – something which is hardly credible in the light of what is known of Theon’s methods. We do know, however, that Burgoyne advertised widely and took subscriptions for the lessons, and that they were published in book form in 1889 as The Light of Egypt; or The Science of the Soul and the Stars, attributed to Burgoyne’s H.B. of L. sobriquet “Zanoni.”

With The Light of Egypt, the secrecy of the H.B. of L.’s documents was largely broken, and they were revealed – to those who could tell – to be fairly unoriginal compilations from earlier occultists, presented with a strongly anti-Theosophical tone. Only the practical teachings were omitted. The book was translated into French by Rene Philipon, a friend of Rene Guenon’s, and into Russian and Spanish, and a paraphrase of it was published in German. We present [B.8] the most important reactions to this work, which has been reprinted frequently up to the present day.After the political upheavals in Tibet in the 1950s, Pallis became active in the affairs of the Tibetan [Tibet] Society, the first Western support group created for the Tibetan people. Pallis also was able to house members of the Tibetan diaspora in his London flat. Pallis also formed a relationship with the young Chögyam Trungpa, who had just arrived in England. Trungpa asked Pallis to write the foreword to Trungpa’s first, autobiographical book, Born in Tibet. In his acknowledgment, Trungpa offers Pallis his “grateful thanks” for the “great help” that Pallis provided in bringing the book to completion. He goes on to say that “Mr. Pallis when consenting to write the foreword, devoted many weeks to the work of finally putting the book in order”.

Pallis studied music under Arnold Dolmetsch, the distinguished reviver of early English music, composer, and performer, and was considered “one of Dolmetsch's most devoted protégés”. Pallis soon discovered a love of early music—in particular chamber music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—and for the viola da gamba. Even while climbing in the region of the Satlej-Ganges watershed, he and his musically-minded friends did not fail to bring their instruments.

Viola da gamba

Pallis taught viol at the Royal Academy of Music, and reconstituted The English Consort of Viols, an ensemble he had first formed in the 1930s. It was one of the first professional performing groups dedicated to the preservation of early English music. They released three records and made several concert tours in England and two tours to the United States.

According to the New York Times review, their Town Hall concert of April 1962 “was a solid musical delight”, the players having possessed “a rhythmic fluidity that endowed the music with elegance and dignity”. Pallis also published several compositions, primarily for the viol, and wrote on the viol’s history and its place in early English music.

The Royal Academy of Music, in recognition of a lifetime of contribution to the field of early music, awarded Pallis an Honorary Fellowship. At age eighty-nine his Nocturne de l’Ephemere was performed at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London; his niece writes that “he was able to go on stage to accept the applause which he did with his customary modesty.” When he died he left unfinished an opera based on the life of Milarepa...

Pallis described "tradition" as being the leitmotif of his writing. He wrote from the perspective of what has come to be called the traditionalist or perennialist school of comparative religion founded by René Guénon, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, and Frithjof Schuon, each of whom he knew personally.Frithjof Schuon (/ˈʃuːɒn/; German: [ˈfʀiːtˌjoːf ˈʃuː.ɔn]) (18 June, 1907 – 5 May, 1998), also known as ʿĪsā Nūr ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad (عيسیٰ نور الـدّين أحمد),[1] was an author of German ancestry born in Basel, Switzerland. He was a spiritual master, philosopher, and metaphysician inspired by the Hindu philosophy of Advaita Vedanta and Sufism and the author of numerous books on religion and spirituality. He was also a poet and a painter...

Schuon's father was a concert violinist and the household was one in which not only music but literary and spiritual culture were present.

Violin

-- Frithjof Schuon, by Wikipedia

As a traditionalist, Pallis assumed the "transcendent unity of religions" (the title of Schuon's landmark 1948 book) and it was in part this understanding that gave Pallis insight into the innermost nature of the spiritual tradition of Tibet, his chosen love. He was a frequent contributor to the journal Studies in Comparative Religion (along with Schuon, Guénon, and Coomaraswamy), writings on both the topics of Tibetan culture and religious practice as well as the Perennialist philosophy.

-- Marco Pallis, by Wikipedia

Burgoyne’s last years were spent in unwonted comfort if, as the Church of Light says, Dr. Henry and Belle M. Wagner – who had been members of the H.B. of L. since 1885 – gave $100,000 to found an organization for the propagation of the Light of Egypt teachings. Out of this grew the Astro-Philosophical Publishing Company of Denver, and the Church of Light itself, reformed in 1932 by Elbert Benjamine (=C.C. Zain, 1882-1951). Beside Burgoyne’s other books The Language of the Stars and Celestial Dynamics, the new company issued in 1900 a second volume of The Light of Egypt. This differs markedly from the first volume, for it is ascribed to Burgoyne’s spirit, speaking through a medium who was his “spiritual successor,” Mrs. Wagner. As the spirit said, with characteristically poor grammar: “Dictated by the author from the subjective plane of life (to which he ascended several years ago) through the law of mental transfer, well known to all Occultists, he is enabled again to speak with those who are still upon the objective plane of life.”

Max Theon wrote to the Wagners in 1909 (the year after his wife’s death), telling them to close their branch of the H.B. of L. [Information given to Mr. Deveney by Henry O. Wagner.] By that time, the Order had virtually ceased to exist as such, while the Wagners continued on their own, channeling doctrinal and fictional works. Their son, Henry O. Wagner, told Mr. Deveney that he, in turn, received books from his parents by the “blending” process, to be described below. In 1963 he issued an enlarged edition of The Light of Egypt, which included several further items from his parents’ records. Some of these are known to have circulated separately to neophytes during the heyday of the H.B. of L. (see Section 10, below), while others were circulated by Burgoyne individually on a subscription basis to his own private students (all of whom were in theory members of the H.B. of L.) from 1887 until his death. These include a large body of astrological materials and also treatises on “Pentralia,” “Soul Knowledge (Atma Bodha)” and other topics. They are perfectly consistent with the H.B. of L. teachings, but appear to have been Burgoyne’s individual production, done after his separation from Peter Davidson, and they are not reproduced here.

-- The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor: Initiatic and Historical Documents of an Order of Practical Occultism, by Joscelyn Godwin

See also

• Hermetic Brotherhood of Light

References

1. Godwin, Chanel, Deveney, 1995, pages 92-97

2. Godwin, Chanel, Deveney, 1995, page 95

3. Godwin, Chanel, Deveney, 1995, page 6

4. Godwin, Chanel, Deveney, 1995, page 44

5. Godwin, Chanel, Deveney, 1995, page 52

Sources

• Godwin, Joscelyn; Chanel, Christian; Deveney, John Patrick (1995), The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor: Initiatic and Historical Documents of an Order of Practical Occultism, Samuel Weiser

• T. Allen Greenfield. The Story of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Light. Looking Glass, 1997.

External links

• The Hermetic Brotherhood Of Luxor at kheper.net

************************************

Lodges of Magic

LUCIFER

Vol. III., No. 14

London

October 15, 1888.

When fiction rises pleasing to the eye,

Men will believe, because they love the lie;

But Truth herself, if clouded with a frown,

Must have some solemn proofs to pass her down."

-- Churchill

One of the most esteemed of our friends in occult research, propounds the question of the formation of “working Lodges” of the Theosophical Society, for the development of adeptship. If the practical impossibility of forcing this process has been shown once, in the course of the theosophical movement, it has scores of times. It is hard to check one’s natural impatience to tear aside the veil of the Temple. To gain the divine knowledge, like the prize in a classical tripos, by a system of coaching and cramming, is the ideal of the average beginner in occult study. The refusal of the originators of the Theosophical Society to encourage such false hopes, has led to the formation of bogus Brotherhoods of Luxor (and Armley Jail?) as speculations on human credulity. How enticing the bait for gudgeons in the following specimen prospectus, which a few years ago caught some of our most earnest friends and Theosophists.

Students of the Occult Science, searchers after truth, and Theosophists who may have been disappointed in their expectations of Sublime Wisdom being freely dispensed by Hindu Mahatmas, are cordially invited to send in their names to . . . ., when, if found suitable, they can be admitted, after a short probationary term, as Members of an Occult Brotherhood, who do not boast of their knowledge or attainments, but teach freely” (at £1 to £5 per letter?), “and without reserve (the nastiest portions of P. B. Randolph’s “Eulis”), “all they find worthy to receive” (read: teachings on a commercial basis; the cash going to the teachers, and the extracts from Randolph and other “ ove-philter” sellers to the pupils!)* [Documents on view at Lucifer Office, viz., Secret MSS. written in the handwriting of----- (name suppressed for past considerations), “Provincial Grand Master of the Northern Section," One of these documents bears the heading, “A brief Key to the Eulian Mysteries,” i.e. Tantric black magic on a phallic basis. No; the members of this Occult Brotherhood “do not boast of their knowledge.” Very sensible on their part: least said soonest mended.]

If rumour be true, some of the English rural districts, especially Yorkshire, are overrun with fraudulent astrologers and fortune-tellers, who pretend to be Theosophists, the better to swindle a higher class of credulous patrons than their legitimate prey, the servant-maid and callow youth. If the “lodges of magic,” suggested in the following letter to the Editors of this Magazine, were founded, without having taken the greatest precautions to admit only the best candidates to membership, we should see these vile exploitations of sacred names and things increase an hundredfold. And in this connection, and before giving place to our friend’s letter, the senior Editor of Lucifer begs to inform her friends that she has never had the remotest connection with the so-called “H(ermetic) B(rotherhood) of L(uxor),” and that all representations to the contrary are false and dishonest. There is a secret body— whose diploma, or Certificate of Membership, is held by Colonel Olcott alone among modern men of white blood— to which that name was given by the author of “Isis Unveiled” for convenience of designation,* [In "Isis Unveiled," vol. ii. p. 308. It may be added that the "Brotherhood of Luxor" mentioned by Kenneth Mackenzie (vide his Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia) as having its seat in America, had, after all, nothing to do with the Brotherhood mentioned by, and known to us, as was ascertained after the publication of “Isis" from a letter written by this late Masonic author to a friend in New York. The Brotherhood Mackenzie knew of was simply a Masonic Society on a rather more secret basis, and, as he stated in the letter, he had heard of, but knew nothing of our Brotherhood, which, having had a branch at Luxor (Egypt), was thus purposely referred to by us under this name alone. This led some schemers to infer that there was a regular Lodge of Adepts of that name, and to assure some credulous friends and Theosophists that the "H. B. of L.” was either identical or a branch of the same, supposed to be near Lahore!!— which was the most flagrant untruth.] but which is known among Initiates by quite another one, just as the personage known to the public under the pseudonym of “Koot Hoomi,” is called by a totally different name among his acquaintance. What the real name of that society is, it would puzzle the “Eulian” phallicists of the “H. B. of L.” to tell. The real names of Master Adepts and Occult Schools are never, under any circumstances, revealed to the profane; and the names of the personages who have been talked about in connection with modern Theosophy, are in the possession only of the two chief founders of the Theosophical Society. And now, having said so much by way of preface, let us pass on to our correspondent’s letter. He writes:

A friend of mine, a natural mystic, had intended to form, with others, a Branch T. S. in his town. Surprised at his delay, I wrote to ask the reason. His reply was that he had heard that the T.S. only met and talked, and did nothing practical. I always did think the T.S. ought to have Lodges in which something practical should be done. Cagliostro understood well this craving of humans for something before their eyes, when he instituted the Egyptian Rite, and put it in practice in various Freemason lodges. There are many readers of Lucifer in ----- shire. Perhaps in it there might be a suggestion for students to form such lodges for themselves, and to try, by their united wills, to develop certain powers in one of the number, and then through the whole of them in succession. I feel sure numbers would enter such lodges, and create a great interest for Theosophy.” “A.”

In the above note of our venerable and learned friend is the echo of the voices of ninety-nine hundredths of the members of the Theosophical Society: one-hundredth only have the correct idea of the function and scope of our Branches. The glaring mistake generally made is in the conception of adeptship and the path thereunto. Of all thinkable undertakings that of trying for adeptship is the most difficult. Instead of being obtainable within a few years or one lifetime, it exacts the unremittent struggles of a series of lives, save in cases so rare as to be hardly worth regarding as exceptions to the general rule. The records certainly show that a number of the most revered Indian adepts became so despite their births in the lowest, and seemingly most unlikely, castes. Yet it is well understood that they had been progressing in the upward direction throughout many previous incarnations, and, when they took birth for the last time, there was left but the merest trifle of spiritual evolution to be accomplished, before they became great living adepts. Of course, no one can say that one or all of the possible members of our friend A.’s ideal Cagliostrian lodge might not also be ready for adeptship, but the chance is not good enough to speculate upon: Western civilization seems to develop fighters rather than philosophers, military butchers rather than Buddhas. The plan “A.” proposes would be far more likely to end in mediumship than adeptship. Two to one there would not be a member of the lodge who was chaste from boyhood and altogether untainted by the use of intoxicants. This is to say nothing of the candidates’ freedom from the polluting effects of the evil influences of the average social environment. Among the indispensable pre-requisites for psychic development, noted in the mystical Manuals of all Eastern religious systems, are a pure place, pure diet, pure companionship, and a pure mind. Could “A.” guarantee these? It is certainly desirable that there should be some school of instruction for members of our Society; and had the purely exoteric work and duties of the Founders been less absorbing, probably one such would have been established long ago. Yet not for practical instruction, on the plan of Cagliostro, which, by-the-bye, brought direful suffering upon his head, and has left no marked traces behind to encourage a repetition in our days. “When the pupil is ready, the teacher will be found waiting,” says an Eastern maxim. The Masters do not have to hunt up recruits in special ----- shire lodges, nor drill them through mystical non-commissioned officers: time and space are no barriers between them and the aspirant; where thought can pass they can come. Why did an old and learned Kabalist like “A.” forget this fact? And let him also remember that the potential adept may exist in the Whitechapels and Five Points of Europe and America, as well as in the cleaner and more “cultured” quarters; that some poor ragged wretch, begging a crust, may be “whiter-souled” and more attractive to the adept than the average bishop in his robe, or a cultured citizen in his costly dress. For the extension of the theosophical movement, a useful channel for the irrigation of the dry fields of contemporary thought with the water of life, Branches are needed everywhere; not mere groups of passive sympathisers, such as the slumbering army of church-goers, whose eyes are shut while the “devil” sweeps the field; no, not such. Active, wide-awake, earnest, unselfish Branches are needed, whose members shall not be constantly unmasking their selfishness by asking “What will it profit us to join the Theosophical Society, and how much will it harm us?” but be putting to themselves the question “Can we not do substantial good to mankind by working in this good cause with all our hearts, our minds, and our strength?” If “A.” would only bring his ----- shire friends, who pretend to occult leanings, to view the question from this side, he would be doing them a real kindness. The Society can get on without them, but they cannot afford to let it do so.

Is it profitable, moreover, to discuss the question of a Lodge receiving even theoretical instruction, until we can be sure that all the members will accept the teachings as coming from the alleged source? Occult truth cannot be absorbed by a mind that is filled with preconception, prejudice, or suspicion. It is something to be perceived by the intuition rather than by the reason; being by nature spiritual, not material. Some are so constituted as to be incapable of acquiring knowledge by the exercise of the spiritual faculty; e.g. the great majority of physicists. Such are slow, if not wholly incapable of grasping the ultimate truths behind the phenomena of existence. There are many such in the Society; and the body of the discontented are recruited from their ranks. Such persons readily persuade themselves that later teachings, received from exactly the same source as earlier ones, are either false or have been tampered with by chelas, or even third parties. Suspicion and inharmony are the natural result, the psychic atmosphere, so to say, is thrown into confusion, and the reaction, even upon the stauncher students, is very harmful. Sometimes vanity blinds what was at first strong intuition, the mind is effectually closed against the admission of new truth, and the aspiring student is thrown back to the point where he began. Having jumped at some particular conclusion of his own without full study of the subject, and before the teaching had been fully expounded, his tendency, when proved wrong, is to listen only to the voice of his self-adulation, and cling to his views, whether right or wrong. The Lord Buddha particularly warned his hearers against forming beliefs upon tradition or authority, and before having thoroughly inquired into the subject.

An instance. We have been asked by a correspondent why he should not “be free to suspect some of the so-called ‘precipitated’ letters as being forgeries,” giving as his reason for it that while some of them bear the stamp of (to him) undeniable genuineness, others seem from their contents and style, to be imitations. This is equivalent to saying that he has such an unerring spiritual insight as to be able to detect the false from the true, though he has never met a Master, nor been given any key by which to test his alleged communications. The inevitable consequence of applying his untrained judgment in such cases, would be to make him as likely as not to declare false what was genuine, and genuine what was false. Thus what criterion has any one to decide between one “precipitated” letter, or another such letter? Who except their authors, or those whom they employ as their amanuenses (the chelas and disciples), can tell? For it is hardly one out of a hundred “occult” letters that is ever written by the hand of the Master, in whose name and on whose behalf they are sent, as the Masters have neither need nor leisure to write them; and that when a Master says, “I wrote that letter,” it means only that every word in it was dictated by him and impressed under his direct supervision. Generally they make their chela, whether near or far away, write (or precipitate) them, by impressing upon his mind the ideas they wish expressed, and if necessary aiding him in the picture-printing process of precipitation. It depends entirely upon the chela's state of development, how accurately the ideas may be transmitted and the writing-model imitated. Thus the non-adept recipient is left in the dilemma of uncertainty, whether, if one letter is false, all may not be; for, as far as intrinsic evidence goes, all come from the same source, and all are brought by the same mysterious means. But there is another, and a far worse condition implied. For all that the recipient of “occult” letters can possibly know, and on the simple grounds of probability and common honesty, the unseen correspondent who would tolerate one single fraudulent line in his name, would wink at an unlimited repetition of the deception. And this leads directly to the following. All the so-called occult letters being supported by identical proofs, they have all to stand or fall together. If one is to be doubted, then all have, and the series of letters in the “Occult World,” “Esoteric Buddhism,” etc., etc., may be, and there is no reason why they should not be in such a case—frauds, clever impostures,” and “forgeries,” such as the ingenuous though stupid agent of the “S .P .R” has made them out to be, in order to raise in the public estimation the “scientific” acumen and standard of his “Principals.”

Hence, not a step in advance would be made by a group of students given over to such an unimpressible state of mind, and without any guide from the occult side to open their eyes to the esoteric pitfalls. And where are such guides, so far, in our Society? “They be blind leaders of the blind,” both falling into the ditch of vanity and self-sufficiency. The whole difficulty springs from the common tendency to draw conclusions from insufficient premises, and play the oracle before ridding oneself of that most stupefying of all psychic anaesthetics— IGNORANCE.