Mirra Alfassaby Wikipedia

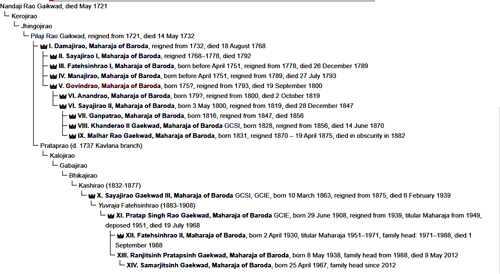

Accessed: 3/5/21

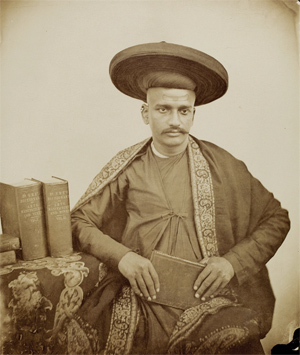

Hurrychund Chintamon had played an important part in the early Theosophical Society and in the move of Blavatsky and Olcott from New York to India. He had been their chief Indian correspondent during 1877-1878, when he was President of the Bombay

Arya Samaj (a Vedic revival movement with which the early Theosophical Society was allied). After Blavatsky and Olcott arrived in Bombay in 1879 and met Chintamon in person, they discovered that he was a scoundrel and an embezzler, and expelled him from the Society. Chintamon came to England in 1879 or 1880, and stayed until 1883, when he returned to make further trouble for the Theosophists in India. Perhaps the fact that Chintamon was in England when Burgoyne first met Theon led some to conclude that they were the same person. But this cannot be the whole story. Ayton claimed very clearly and repeatedly that he had proof of Burgoyne’s being in company with Chintamon. In a letter in the private collection, [The Rev W. A.] Ayton writes:

I have since discovered that Hurrychund Chintaman the notorious Black Magician was in company with Dalton at Bradford. By means of a Photograph I have traced him to Glasgow & even to Banchory, under the alias of Darushah Chichgur. Friends in London saw him there just before his return to India. This time coincides with that when I noticed a great change in the management. Chintaman had supplied the Oriental knowledge as he was a Sanskrit scholar & knew much. Theon was Chintaman! Friends have lately seen him in India where he is still at his tricks.

Before her disillusion[ment] with Chintamon, Blavatsky had touted him to the London Theosophists as a “great adept.” After the break that followed on her meeting with him in person, Chintamon allied himself to the rising Western opposition to esoteric Buddhism exemplified by Stainton Moses, C.C. Massey, William Oxley, Emma Hardinge Britten, Thomas Lake Harris, and others. From this formidable group, Burgoyne first contracted the hostility towards Blavatsky’s enterprise that would mark all his writings.

Chintamon also appears in connection with “H.B. Corinni,” the otherwise unidentifiable (and variously spelled) “Private Secretary” of Theon, who was thought by the police to be just another of Burgoyne’s aliases. Ayton, however, believed Corinni to be Chintamon’s son, who he said offered Blavatsky’s old letters for sale to the President of the London Branch of the Theosophical Society,

Charles Carleton Massey. [Ayton to unnamed American neophyte, 11 June 1886, based on what he had been told by Massey.] The flaw in Ayton’s thesis is of course the existence of a real and independent Max Theon, of whom we, unlike Ayton, have documentary evidence. Nonetheless, after more than a hundred years, the whole tangle of misidentifications involving Chintamon, “Christamon,” and “Metamon” [see B.9.c-3] with the Order cannot be entirely resolved.

-- Excerpt from The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor: Initiatic and Historical Documents of an Order of Practical Occultism, by Joscelyn Godwin

Max Théon (17 November 1848 – 4 March 1927) perhaps born Louis-Maximilian Bimstein, was a Polish Jewish Kabbalist and Occultist. In London while still a young man, he inspired The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor in 1884...

There is some dispute over whether Théon taught Blavatsky at some stage; the Mother in The Agenda says he did...

Théon gathered a number of students, including Louis Themanlys and Charles Barlet, and they established the "Cosmic Movement". This was based on material, called the Cosmic Tradition, received or perhaps channelled by Théon's wife. They established the journal Cosmic Review, for the "study and re-establishment of the original Tradition"...

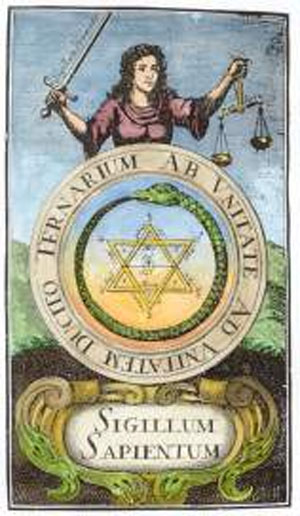

Louis Themanlys was a friend of Matteo Alfassa, the brother of Mirra Alfassa (who would later associate with Sri Aurobindo and become The Mother), and in 1905 or 1906 Mirra travelled to Tlemcen to study occultism under Théon (Sujata Nahar, Mirra the Occultist). The Mother mentions that Sri Aurobindo and Théon had independently and at the same time arrived at some similar conclusions about evolution of human consciousness without having met each other. The Mother's design of Sri Aurobindo's symbol is very similar to that of Théon's, with only small changes in the proportions of the central square (Mother's Agenda, vol 3, p. 454, dated December 15, 1962).

-- Max Théon, by Wikipedia

Mirra Alfassa

Personal

Born: Blanche Rachel Mirra Alfassa, 21 February 1878, Paris, France

Died: 17 November 1973 (aged 95), Pondicherry, India

Resting place: Pondicherry, India

Religion: Hinduism

Nationality: French, Indian

Notable work(s): Prayers And Meditations, Words of Long Ago, On Thoughts and Aphorisms, Words of the Mother

Pen name: The Mother

Institute: Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Auroville

Religious career

Students: Satprem, Nolini Kanta Gupta, Nirodbaran, Amal Kiran, Pavitra

Mirra Alfassa (21 February 1878 – 17 November 1973), known to her followers as The Mother, was a French spiritual guru, an occultist and a collaborator of Sri Aurobindo, who considered her to be of equal yogic stature to him and called her by the name "The Mother". She founded the Sri Aurobindo Ashram and established Auroville as a universal town; she was an influence and inspiration to many writers and spiritual personalities on the subject of Integral Yoga.

Mirra Alfassa was born in Paris in 1878 to a Sephardic Jewish bourgeois family. In her youth, she traveled to Algeria to practice occultism along with Max Théon. After returning, while living in Paris, she guided a group of spiritual seekers. In 1914, she traveled to Pondicherry, India and met Sri Aurobindo and found in him "the dark Asiatic figure" of whom she had had visions and called him Krishna. During this first visit, she helped publish a French version of a periodical Arya which serialized most of Sri Aurobindo's post-political prose writings. During First World war she was oblised to leave Pondicherry. Thereafter a 4-year stay in Japan, in 1920, she returned to Pondicherry for good. Gradually, as more and more people joined her and Sri Aurobindo, she organised and developed Sri Aurobindo Ashram. In 1943, she started a school in the ashram and in 1968 established Auroville, an experimental township dedicated to human unity and evolution. She left her body on 17 November 1973 in Pondicherry.

The experiences of the last thirty years of Mirra Alfassa's life were captured in the 13-volume work Mother's Agenda by Satprem who was one of her followers.

Early life

Childhood Mirra Alfassa as a child c. 1885

Mirra Alfassa as a child c. 1885 Mirra Alfassa

Mirra AlfassaMirra Alfassa was born in 1878 in Paris to Moïse Maurice Alfassa a Turkish Jewish father, and Mathilde Ismalun an Egyptian Jewish mother. They were a bourgeois family, and Mirra's full name at birth was Blanche Rachel Mirra Alfassa. She had an elder brother, Mattéo Mathieu Maurice Alfassa, who later held numerous French governmental posts in Africa. The family had just migrated to France a year before Mirra was born. Mirra was close to her grandmother Mira Ismalum (née Pinto), who was a neighbour and who was one of the first women to travel alone outside Egypt.[1][2]

Mirra learnt to read at the age of seven and joined school very late at the age of nine. She was interested in various fields of art, tennis, music and singing, but was a concern to her mother owing to an apparent lack of permanent interest in any particular field.[3][4] By the age of 14 she had read most of the books in her father's collection, which is believed to have helped her achieve mastery of French.[5] Her biographer Vrekhem notes that Mirra had various occult experiences in her childhood but knew nothing of their significance or relevance. She kept these experiences to herself as her mother would have regarded occult experiences as a mental problem to be treated.[6] Mirra especially recalls at the age of thirteen or fourteen having a dream or a vision of a luminous figure whom she used to call Krishna but had never seen before in real life.[7][8][9]

As an artist and traveller Mirra Alfassa at the age of 24 with son Andre, circa 1902In Paris

Mirra Alfassa at the age of 24 with son Andre, circa 1902In ParisIn 1893 after graduating from school, Mirra joined Académie Julian[10][11] to study art. Her grandmother Mira introduced her to Henri Morisset, an ex-student of the Académie; they were married on 13 October 1897.[12] Both were well off and worked as artists for the next ten years, during an era known for having many impressionist artists. Her son André was born on 23 August 1898. Some of Alfassa's paintings were accepted by the jury of Salon d'Automne and were exhibited in 1903, 1904 and 1905.[13] She recalls herself being a complete atheist at this time, yet was experiencing various memories which she found were not mental formations but spontaneous experiences. She kept those experiences to herself and developed an urge to understand their significance. She came across the book Raja yoga by Swami Vivekananda, which provided some of the explanations she was looking for. She also received a copy of the Bhagavad Gita in French which helped her considerably in learning more about these experiences.[14]

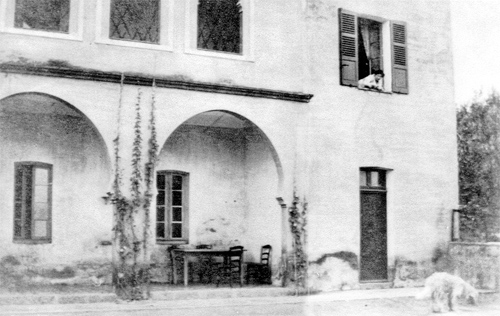

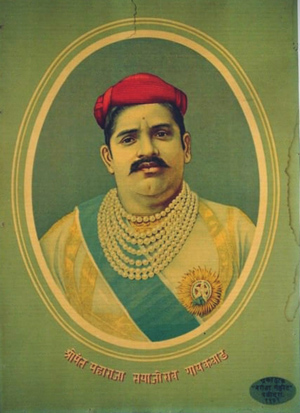

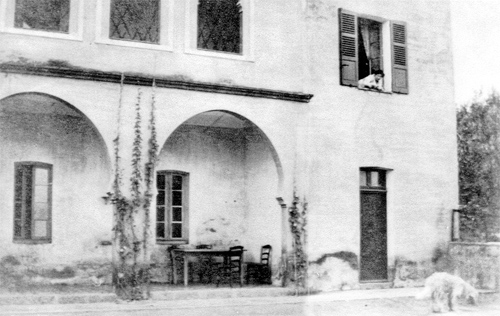

Max Théon and Alma Théon Mirra Alfassa in Theon's house at Tlemcen, Algeria (1906–1907)

Mirra Alfassa in Theon's house at Tlemcen, Algeria (1906–1907)During this time Mirra made the acquaintance of Louis Thémanlys who was the head of the Cosmic Movement, a group started by Max Théon. Through reading a copy of Cosmic Review, she attended Thémanlys's speeches and became active in the group. For the first time, on 14 July 1906, she journeyed alone to the Algerian city of Tlemcen to meet with Max Théon and his wife Alma Théon. She consequently travelled twice more, in 1906 and 1907, to their estate at Tlemcen and there practised and experimented with the teachings of Max Théon & Alma Théon.[15]

Mirra Alfassa and Henri separated in 1908; she then moved to 49 Rue des Lévis, Paris, living alone in a small apartment and involving herself in discussions with Buddhists and Cosmic movement circles. During this time she also made the acquaintance of Madame David Néel.[16] Mirra married Paul Richard in 1911 who after serving four years in the army had involved himself in philosophy & theology. He had come to know Mirra when he was in discussions with Max Théon. Vrekhem, a biographer of Mirra, informs that Richard was undergoing a legal problem in inheriting children from his first marriage to a Dutch woman, and had asked Mirra for help which she had accepted by marrying him.[17]

First meetings with Aurobindo and Japan Dorothy Hodgson (Dutta), Mirra Alfassa, Paul Richard & Japanese friends in Tokyo c.a 1918

Dorothy Hodgson (Dutta), Mirra Alfassa, Paul Richard & Japanese friends in Tokyo c.a 1918Richard was also an aspiring politician and had attempted to win election to the French senate from Pondicherry, which was then under French control. Despite his initial failure he wanted to make a second attempt, and on 7 March 1914 Mirra along with Richard set sail to India and reached Pondicherry by 29 March.[18][19] After reaching Pondicherry, they fixed an appointment with Sri Aurobindo who was then settled in Pondicherry and had suspended all his activity for Indian independence from British rule. When she first met Sri Aurobindo, Mirra recognized in him the person whom she used to see in her dreams. During a later meeting, she experienced a complete silence of the mind, free from any thought.[20]

Richard lost the elections to Paul Bluysen whom he had supported in previous elections. Richard decided to publish a review of the yoga of Aurobindo, and to be called Arya and be bilingual in both English and French. The Journal was first published on 15 August 1914 and ran for the next six and half years. Consequent journals published were later made into complete books.[21] By this time World War I had erupted and Indian revolutionaries were being prosecuted by the British for being spies of the German army. Although Aurobindo had totally dispensed his activities against British rule he was considered unsafe and all the revolutionaries were asked to move to Algeria. Aurobindo had refused this offer, so the British had written to the French government in Paris asking to hand over revolutionaries staying at French Pondicherry. This request came to Mirra's brother, Mattéo Alfassa, who by then was foreign minister and who filed the request under other working files never to be looked upon again.[22][23]

On the insistence of the British in 1915, Richard was ordered to move out of Pondicherry. After an unsuccessful attempt to stay, both Mirra and Richard left for Paris on 22 February 1915. After a few years Richard was ordered to promote French trade in Japan (which was then an ally of France and Britain) and China. Mirra left for Japan along with Richard, never to return to Paris again.[24]

Mirra and Richard stayed in Japan and made acquaintances among the Indian community. Their time in Japan was relatively peaceful, and they spent the following four years there. On 24 April 1920 Mirra returned with Richard to Pondicherry[25][26] accompanied by Dorothy Hodgson. Mirra moved to live near Aurobindo in the guest house at Rue François Martin. Richard did not stay long in India; he spent a year traveling around North India returning to France and remarried in England after divorcing Mirra. After working a few years as a professor in the United States he died in 1968.[27] On 24 November 1920 due to a storm and heavy rain, Aurobindo asked Mirra and Dorothy Hodgson (later known as Dutta) to move into Aurobindo's house and she started living in the house along with other residents. [28][29]

Foundation of the ashram

Integral yogaWith time many influenced by the Arya Magazine and others who had heard about Aurobindo started to come to his residence either permanently to reside or to practise Aurobindo's yoga. Mirra was initially not totally accepted by the other household members and was considered an outsider. Aurobindo considered her to be of equal yogic stature and started calling her "the mother", and she was known to the whole community as such from then on. Around 1924 onwards Mirra was starting to organise the day-to-day functioning of the household and slowly the house was turning into an ashram with many followers flowing in every day.[30] After 1926 Aurobindo started to retire from regular activities and put his complete focus towards yogic practises. The community had grown to 85 members by then and the group had slowly turned into a spiritual ashram.

Integral yoga and the Siddhi DayOn 24 November 1926, later declared as Siddhi Day (Victory Day) and still celebrated by Sri Aurobindo Ashram,[31] Mirra and Aurobindo declared that overmind consciousness had manifested directly in physical consciousness, allowing the possibility for human consciousness to be directly aware and be in the overmind consciousness[note 1].

Aurobindo had received a few complaints against Mirra on the daily running of the ashram. To settle this matter in finality Aurobindo declared 'The Mother' to be in sole charge of further activities of the ashram through a letter in April 1930.[32] By August 1930, the ashram members had grown to a number of 80 to 100 residents, a self-sustaining community with all basic amenities fulfilled. [33]

Aurobindo and Mirra's work and principles of yoga was named by them: integral yoga, an all-embracing yoga. This yoga was in variance with older ways of yoga because the follower would not give up the outer life to live in a monastery, but would be present in regular life and practise spirituality in all parts of life. [34]

By 1937 the ashram residents had grown to more than 150, so there was a need for an expansion of buildings and facilities, helped by Diwan Hyder Ali, the Nizam of Hyderabad who had made a grant to the ashram for further expansion. Under the guidance of Mirra, Antonin Raymond, the chief architect, assisted by Franticek Sammer and George Nakashima, constructed a dormitory building. By this time the second world war erupted delaying the construction but was finally completed after ten years and was named Golconde.[35] In 1938 Margaret Woodrow Wilson, the daughter of US President Woodrow Wilson, came to the ashram and chose to remain there for the rest of her life.[36]

By 1939 World War Two had broken out. Although some of the members of the ashram may have supported Hitler indirectly because Britain was attacked, both Mirra and Aurobindo publicly declared their support for the Allied forces, mainly by donating to the Viceroy's war fund, much to the surprise of many Indians.[37]

School in ashram and death of Sri AurobindoOn 2 December 1943 Mirra started a school for about twenty children inside the ashram. She considered this was a considerable movement away from usual life in the ashram, which was until then about practising total renunciation of the outside world. However she found that the school would gradually align to the principles of Sri Aurobindo's integral yoga.[38] The school later became known as the Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education. From 21 February 1949 she started a quarterly magazine called "The Bulletin" in which Aurobindo published a series of eight articles under the title "The supramental manifestation upon earth" wherein for the first time he wrote about transitional being between man and superman.[39]

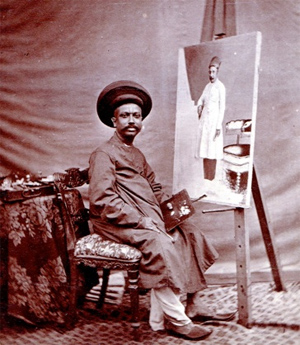

Mirra's painting: ‘Divine Consciousness Emerging from the Inconscient’, 1920–1925

Mirra's painting: ‘Divine Consciousness Emerging from the Inconscient’, 1920–1925Aurobindo's health had deteriorated and he died on 5 December 1950. This was a very difficult experience for Mirra.[39] All the activities in the ashram were suspended for twelve days, after which Mirra had to decide the future course of the ashram. Mirra decided to take up the entire work of the ashram and also to continue the integral yoga internally. The years from 1950 to 1958 were the years where she was mostly seen by her disciples.[40]

Pondicherry, IndiaOn 15 August 1954 French Pondicherry became a union territory of India. Mirra declared dual citizenship for India and France.[41] Jawaharlal Nehru visited the ashram on 16 January 1955 and met with Mirra for a few minutes. This meeting cleared many doubts he had about the ashram. During his second visit to the ashram on 29 September 1955, his daughter Indira Gandhi accompanied him. Mirra had a profound effect on her, which developed into a close relationship in later years.[42] Mirra continued to teach French after the death of Aurobindo. She started with just simple conversations and recitations, which later expanded into deeper discussions about integral yoga where she would read a passage from Aurobindo's or her own writings and comment on them. These sessions grew into a seven-volume book called Questions and Answers. [43]

After 1958, Mirra slowly started to withdraw from outer activities. The year 1958 was also marked by greater progress in yoga.[44] She stopped all her activities from 1959 onwards to devote herself completely towards yoga. On 21 February 1963, on her 85th birthday, she gave her first darshan from the terrace that had been built for her. From then on she would be present there, on darshan days where visitors below would gather around to catch a glimpse of her.[45] Mirra Alfassa regularly met with one of her disciples Satprem. He had recorded all their conversations, which later he gathered in a volume of 13 books called Mother's Agenda.

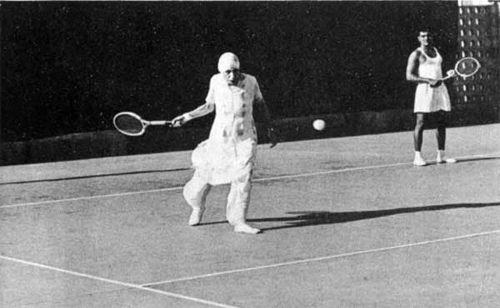

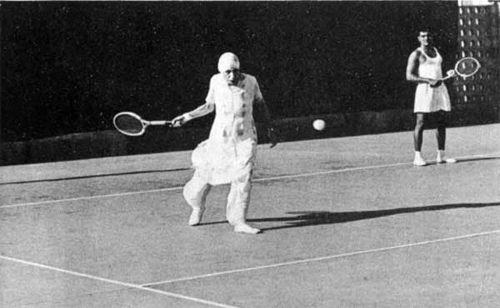

Mirra Alfassa playing tennisEstablishing Auroville

Mirra Alfassa playing tennisEstablishing AurovilleMain article: Auroville

Matrimandir, in Auroville, near Pondicherry

Matrimandir, in Auroville, near PondicherryMirra had published an article titled "The Dream" in which she suggested a place on earth that no nation could claim as its sole property, for all humanity with no distinction.[46] In 1964 it was finally decided to build this city. On 28 February 1968 they drew up a charter for the city, Auroville, meaning City of the Dawn (derived from the French word aurore), a model universal township where one of the aims would be to bring about human unity. The city still exists and continues to grow. [47] Today Auroville is managed by a foundation set up by the Indian government.

Later yearsMany politicians visited Mirra on a regular basis for her guidance. She had visits from V.V. Giri, Nandini Satpathy, Dalai Lama, and especially Indira Gandhi who was in close contact with her and often visited her for guidance. [48] By the end of March 1973 she became critically ill. After 20 May 1973 all meetings were cancelled. She gave her final darshan on 15 August of the same year, visiting the outside balcony where thousands of followers were waiting to catch a glimpse of her. Mirra died at 7:25 p.m on 17 November 1973. On 20 November she was buried next to Aurobindo in the courtyard of the main ashram building.[49]

Mirra Alfassa on a 1978 stamp of IndiaReferences

Mirra Alfassa on a 1978 stamp of IndiaReferences

Notes1. A detailed description of the Overmind is provided in Book I ch.28, and Book II ch.26, of Aurobindo's philosophical opus The Life Divine

Citations1. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 4–7.

2. Mother's Chronicles Bk I; Mother on Herself – Chronology p.83.

3. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 8.

4. Iyengar 1978, pp. 6–7.

5. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 10.

6. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 11–13.

7. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 14.

8. Bulletin of the Sri Aurobindo Centre of Education, 1976 p.14, Mother on Herselfpp.17–18.

9. Bulletin 1974 p.63.

10. "The Mother". sriaurobindoashram.org. 2013. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

11. Mirra Alfassa, paintings and drawings, P. 157-158

12. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 15–20.

13. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 24.

14. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 29.

15. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 37–67.

16. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 73–75.

17. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 84.

18. Interview with Prithwindra Mukherjee, The Sunday Standard, 15 June 1969; The Mother by Prema Nandakumar, National Book Trust, 1977, p9.

19. Karmayogi no date, Van Vrekhem 2001.

20. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 140–155.

21. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 160–172.

22. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 175–177.

23. Purani 1982, pp. 9–12[full citation needed]

24. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 178–180.

25. Iyengar 1978, p. 182.

26. Collected Works 1978, volume 8, pp. 106–107.

27. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 215–216.

28. Vrekhem 2004, p. 225.

29. Mother's Agenda 1979, volume 2, pp. 371–372.

30. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 228–248.

31. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 250–251.

32. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 258–259.

33. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 286–287.

34. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 270–271.

35. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 303–305.

36. Nirodbaran 1972, Karmayogi[full citation needed]

37. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 310–326.

38. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 334–335.

39. Jump up to:a b Vrekhem 2004, pp. 353–354.

40. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 385.

41. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 408–409.

42. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 412–413.

43. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 414.

44. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 479–486.

45. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 541.

46. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 547–549.

47. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 559–562.

48. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 573.

49. Vrekhem 2004, pp. 593–598.

Bibliography• Heehs, Peter (2008), The Lives of Sri Aurobindo, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14098-0

• Vrekhem, Georges Van (2004), the Mother the story of her life, Rupa & Co, ISBN 8129105934

• Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D., eds. (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, New York: Facts on File Inc, ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9

Further reading• Anon., The Mother – Some dates

• Aurobindo, Sri (1972). Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo (Birth Centenary ed.). Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry.

• (1972b) The Mother, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry

• Iyengar, K. R. S. (1978). On the Mother: The Chronicle of a Manifestation and Ministry (2nd ed.). Sri Aurobindo International Centre of Education / Pondicherry. (2 vols, continuously paginated)

• Alfassa, Mirra (1977) The Mother on Herself, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry

• Collected Works of the Mother (Centenary ed.). Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry. 1978(17 vol set)

• Mother's Agenda. New York, NY: Institute for Evolutionary Research. 1979(13 vol set)

o (date?) Flowers and Their Messages, Sri Aurobindo Ashram

o (date?) Flowers and Their Spiritual Significance, Sri Aurobindo Ashram

• Das, Nolima ed., (1978) Glimpses of the Mother's Life vol.1, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry

• Mukherjee, Prithwindra (2000), Sri Aurobindo: Biographie, Desclée de Brouwer, Paris

• Nahar, Sujata (1986) Mother's chronicles Bk. 2. Mirra the Artist, Paris: Institut de Recherches Evolutives, Paris & Mira Aditi, Mysore.

o (1989) Mother's chronicles Bk. 3. Mirra the Occultist. Paris: Institut de Recherches Evolutives, Paris & Mira Aditi, Mysore.

• K.D. Sethna, The Mother, Past-Present-Future, 1977

• Satprem (1982) The Mind of the Cells (transl by Francine Mahak & Luc Venet) Institute for Evolutionary Research, New York, NY

• Van Vrekhem, Georges: The Mother – The Story of Her Life, Harper Collins Publishers India, New Delhi 2000, ISBN 81-7223-416-3 (see also Mother meets Sri Aurobindo – An excerpt from this book)

• Van Vrekhem, Georges: Beyond Man – The Life and Work of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother, HarperCollins Publishers India, New Delhi 1999, ISBN 81-7223-327-2

Partial bibliography• Commentaries on the Dhammapada, Lotus Press, Twin Lakes, WI 2004, ISBN 0-940985-25-X

• Flowers and Their Messages, Lotus Press, Twin Lakes, WI ISBN 0-941524-68-X

• Search for the Soul in Everyday Living, Lotus Press, Twin Lakes, WI ISBN 0-941524-57-4

• Soul and Its Powers, Lotus Press, Twin Lakes, WI ISBN 0-941524-67-1

External links• Writings by The Mother