by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/8/23

Vyasa too, the son of Parasara before mentioned, has decided, that 'the Veda with its Angas, or the six compositions deduced from it, the revealed system of medicine, the Puranas, or sacred histories, and the code of Menu were four works of supreme authority, which ought never to be shaken by arguments merely human.’

It is the general opinion of Pandits, that Brahma taught his laws to Menu in a hundred thousand verses, which Menu explained to the primitive world, in the very words of the book now translated, where he names himself, after the manner of ancient sages, in the third person, but in a short preface to the law tract of Nared, it is asserted, that 'Menu, having written the laws of Brahma in a hundred thousand slocas or couplets, arranged under twenty-four heads in a thousand chapters, delivered the work to Nared, the sage among gods, who abridged it, for the use of mankind, in twelve thousand verses, and gave them to a son of Bhrigu, named Sumati, who, for greater ease to the human race, reduced them to four thousand; that mortals read only the second abridgement by Sumati, while the gods of the lower heaven, and the band of celestial musicians, are engaged in studying the primary code, beginning with the fifth verse, a little varied, of the work now extant on earth; but that nothing remains of NARED’s abridgement, except an elegant epitome of the ninth original title on the administration of justice.' Now, since these institutes consist only of two thousand six hundred and eighty five verses, they cannot be the whole work ascribed to Sumati, which is probably distinguished by the name of the Vriddha, or ancient Manava, and cannot be found entire; though several passages from it, which have been preserved by tradition, are occasionally cited in the new digest.

A number of glosses or comments on Menu were composed by the Munis, or old philosophers, whose treatises, together with that before us, constitute the Dherma sastra, in a collective sense, or Body of Law; among the more modern commentaries, that called Medhatithi, that by Govindaraja, and that by Dharani-Dhera, were once in the greatest repute; but the first was reckoned prolix and unequal; the second concise but obscure; and the third often erroneous. At length appeared Culluca Bhatta; who, after a painful course of study and the collation of numerous manuscripts, produced a work, of which it may, perhaps, be said very truly, that it is the shortest, yet the most luminous, the least ostentatious, yet the most learned, the deepest, yet the most agreeable, commentary ever composed on any author ancient or modern, European or Asiatick. The Pandits care so little for genuine chronology, that none of them can tell me the age of Culluca, whom they always name with applause; but he informs us himself, that he was a Brahmen of the Varendra tribe, whose family had been long settled in Gaur or Bengal, but that he had chosen his residence among the learned, on the banks of the holy river at Casi. His text and interpretation I have almost implicitly followed, though I had myself collated many copies of Menu, and among them a manuscript of a very ancient date: his gloss is here printed in Italicks; and any reader, who may choose to pass it over as if unprinted, will have in Roman letters an exact version of the original, and may form some idea of its character and structure, as well as of the Sanscrit idiom which must necessarily be preserved in a verbal translation; and a translation, not scrupulously verbal, would have been highly improper in a work on so delicate and momentous a subject as private and criminal jurisprudence.

Should a series of Brahmens omit, for three generations, the reading of Menu, their sacerdotal class, as all the Pandits assure me, would in strictness be forfeited; but they must explain it only to their pupils of the three highest classes; and the Brahmen, who read it with me, requested most earnestly, that his name might be concealed; nor would he have read it for any consideration on a forbidden day of the moon, or without the ceremonies prescribed in the second and fourth chapters for a lecture on the Veda: so great, indeed, is the idea of sanctity annexed to this book, that, when the chief native magistrate at Banares endeavoured, at my request, to procure a Persian translation of it, before I had a hope of being at any time able to understand the original, the Pandits of his court unanimously and positively refused to assist in the work; nor should I have procured it at all, if a wealthy Hindu at Gaya had not caused the version to be made by some of his dependants, at the desire of my friend Mr. [Jacques Louis Law de Clapernon? or Baron Jean Law de Lauriston?] Law. [1776]

-- Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Menu, According to the Gloss of Culluca. Comprising the Indian System of Duties, Religious and Civil, Verbally translated from the original Sanscrit, With a Preface, by Sir William Jones

Perhaps the most important name connected with the EzV in this early period is that of Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil Duperron (1731-1805), who quotes a long passage from it in the "Discours Preliminaire" to his Zend-Avesta (1771:1, I. lxxxiii-lxxxvii). Anquetil adds the interesting remark, that "the manuscript brought back to France by Mr. de Modave [Maudave] [and delivered to Voltaire] originally comes from the papers of Mr. Barthelemy, second of the Council at Pondicherry, who probably had the original translated by the Company's interpreters under his orders."...

The Ezourvedam Manuscripts

The Pondicherry Manuscripts

The manuscripts which Ellis saw in Pondicherry in 1816 can no longer be traced. The latest exhaustive reference to them is by Father Hosten, in three successive publications. He says (1923:137n28) that "what remains of them is in my possession now for study, lent to me by the authorities of the Catholic Mission of Pondicherry." Two years earlier he stated (1921:500; cf. also 1922:65) that manuscripts of the archives of the Procure des Missions Etrangeres de Paris, "bound up in two large tomes," had been with him, at Darjeeling, since the end of 1918. I am not sure how to interpret his reference to the size of the EzV: "The manuscripts contain portions of the Ezour-Vedam (Yajurveda), about which there has been no little commotion in Oriental circles since 1761, in Voltaire's time; but, whereas the Ezour-Vedam printed at Yverdon in 1778 contains only 8 books, the Pondicherry manuscripts of the Ezour-Vedam must have originally contained 42 books" (1922:65). For a reason which he explains no further, he seems to believe (1922:66; cf. also 1921:500) that "large portions still existing in 1816 have been lost."

In the description of manuscript No. 3, Ellis (1822:22) adds a remark on the handwriting of the entire collection: "The handwriting of this manuscript differs from that in which the Ezour Vedam is written, but agrees with that of the Sama Vedam and of all the others in which Sanscrit and French are found together." In other words, according to Ellis the handwriting of the EzV manuscript is different from that of all other texts in the collection. On the other hand, Hosten (1922:65-6; cf. also 1921:500; 1923:138n28) reports as follows on a visit to Pondicherry, in 1921: "During my visit to Pondicherry, a few minutes' search in the Cathedral Church registers, where many entries were in Father Mosac's handwriting, showed clearly that all the Pondicherry manuscripts on the Vedas, both transliterations and translations, are by Father Mosac. ... I had a photograph made of some of the entries in the Cathedral Church registers, signed by Father Mosac, and as I have photographs of parts of his translations, even the most exacting critics will be able to satisfy themselves as to the identity of the writings." As indicated earlier, Hosten believes that Mosac is the author of the French translation only, not of the Sanskrit original. "The fact that at times, he confesses that he does not understand the Sanskrit text proves also that he is not the author of the Sanskrit texts" (1922:65; cf. 1921:500; 1923:138n28). If Hosten's reference is indeed to marginal notes to the Sanskrit sections, in Mosac's handwriting, it is also possible that these manuscripts were Mosac's own copies, of both the French and the Sanskrit sides, of earlier documents, in which he occasionally was unable to establish the correspondence between the two. As Castets (1921:577) puts it: "even if the whole could be identified to be in the handwriting of the said Father, the only safe conclusion would be that this missionary had written down the document found in the Pondicherry Mission Library, but, not necessarily that he was rather the discoverer or the translator."

Although he does not explicitly say so, Castets himself seems to have seen the Pondicherry manuscripts, some time before 1935. He reports (1935:10) that "in the course of time the collection has been bound in two volumes, and is even considerably deteriorated." He also suggests (1935:12-3) that there are variant readings in the different manuscripts: "If Mr. Ellis had been able to compare the manuscript that was handed to him with the Yverdon edition, he would have discovered that if one confronts the three manuscripts -- Voltaire's, A. du Perron's, and the one found at the Mission -- with one another, not one is found to be identical with any other, at least not as far as the contents are concerned." And he adds (14), about Ellis' No. 2: "The Ezour Vedam in this copy-book contains eight books, even as the printed Vedam; but, as I indicated earlier, it differs from the other three manuscripts by many additions, in the form of introductions, or even additions of several of these books." Unfortunately, it is no longer possible to verify these data.

Castets also has different ideas on the original owner -- and annotator -- of the Pondicherry manuscripts. He quotes (1935:45) a letter by Calmette to show that, to acquire manuscripts in India, paying money for them was not necessarily a sufficient condition: "Less than six years ago two missionaries, one in Bengal and another one right here [i.e., in the Telugu area], have been misled. Mr. Didier, an engineer for the King, gave 60 roupies for a so-called Vedam, in favor of Father Pons, the superior of Bengal." From this Castets (46) draws the conclusion, first that Calmette fully realized that the Vedas at Pondicherry were nothing more than "counterfeits, composed and sold by Brahmin sharks, to impose upon them" and, second, that Calmette "provides us the name of the principal supplier of the collection, namely Father Pons, who is also the famous marginal annotator of these Pseudo-vedams." And Castets concludes (46) with a touching description of Pons' activities: "Father Pons, for a long time a missionary among the Telugus, Superior of the Mission in Bengal from 1728 to 1733, eminent sanskritist, author of a treatise on Sanskrit prosody, great collector of Sanskrit books, who finally, reduced by age and exhaustion, to forced leisures, at the seat of the Mission, in Pondicherry, enjoyed himself revising his past acquisitions, even in the year of his death which came in December 1751 or January 1752." The following year Srinivasan repeats (1936:132) that Father Pons "was a victim of the famous hoax perpetrated in connection with the Yajur Veda," on the authority of Castets.

Voltaire's and Anquetil's Manuscripts

As far as Voltaire's copy of the EzV is concerned, we know that he received it from Maudave, a well known figure in French colonial history. Louis-Laurent de Federbe, chevalier and later comte de Maudave, was born on 25 June 1725 at the castle of Fayet, near Grenoble. From April to July 1756 he took part in Louis XVs expedition to Menorca. In May 1757 he left for India, with Count Lally. He arrived in Pondicherry on 28 April 1758, and participated in the capture of Fort St. David and the siege of Madras. On 26 June 1758 he married Marie Nicole, the daughter of the commander of Karikal, Abraham Pierre Porcher des Oulches. When all senior officers were recalled in September 1759, Maudave returned to France; he arrived at Lorient on 2 February 1760. During the voyage he wrote part of a "Memoire sur les establissemens a la cote de Coromandel," which he completed after his arrival on Menorca, on 6 December 1760. We have seen earlier that it was on his way from Paris to Mahon that Maudave visited Voltaire at Ferney.

On 28 March 1761 Maudave again embarked for India, aboard the Fidelle. He arrived at the Ile de France (Mauritius) just after the news of the fall of Pondicherry (14 January 1761) reached the island. He convinced the governor to give him the Fidelle, and he sailed for Negapatam, where he arrived on 4 April 1762. Under the pretext of lightening the suffering of his compatriots in India, he actually tried to rally them around Yusuf Khan, of Madura. Not only did he lose the confidence of the Dutch and had to move to Tranquebar, he also lost the support of the Council of the Ile de France who terminated his mission on 31 January 1764. Seven weeks later he left Tranquebar and joined his family on Mauritius. Maudave spent two years and a half on the Ile de France, managing a large estate but not politically inactive. When the General Assembly at Port-Louis decided to send two representatives to Paris to discuss the colonization of Madagascar, Maudave was one of them. He arrived at Lorient on 9 May 1767. Ten months later he sailed again, and, via the Ile de France, reached Fort Dauphin on 5 September 1768, as the "commander on behalf of the King of the island of Madagascar." After two years he was recalled, and by the end of 1770 he left Madagascar for Mauritius.

But, once again, in 1773, Maudave sailed for India, "in search of a military career under one of the Indian princes." He traveled to Calcutta, Lucknow, Delhi, and Hyderabad; after four years he was taken seriously ill, and died at Masulipatam, on 22 December 1777. The British Government, for obvious reasons, refused to grant him the honors due to his rank.

From this short biography Maudave appears to us as the prototype of the eighteenth century adventurer. "His life was a true novel;" and, "intelligent, courageous, and a natural wanderer, Maudave is one of those who have gone everywhere but never arrived at anything." Yet, he also took an active interest in all parts of the world he visited, especially India. From the time of his first return from India, in 1760, when he visited Voltaire and when d'Alembert described him as "a man of intelligence and merit" (Best. 8496) and "an Indian" (Best. 8567), his advice was also sought and appreciated by the foreign minister of Louis XV. "Choiseul soon recognized Maudave as someone unusually well acquainted with matters Indian, on whose information he could rely: the puzzle of Hinduism, Oriental customs, the location of the warriors and neutrals, he knows everything, gives his opinion on everything. And this good soldier occasionally also turns out to be an accomplished economist. He bristles with ideas on the commercial possibilities of our establishments and on the ways to reorganize them. He supports his speeches with writings which he composed during the long journey."

To be sure, the religions of India were not Maudave's primary concern. He states himself, at the end of the unpublished letter to Voltaire: "I feel I have neither the energy nor the knowledge, Sir, that would be required to explain to you here and now the foundations of Indian religion. To tell you the truth, this subject has roused my curiosity only intermittently. The political situation of the country, its history, and the ways and means to make our Establishments in it more flourishing, have occupied most of my time. These things appeal more to my taste and interest me more professionally. The abominable superstitions of these peoples arouse my indignation. They are a disgrace to human reasoning. But is there any place on the earth where reason is not corrupted by superstition?" Yet, he was also not totally uninterested in the religions of India. We are told by d'Alembert (Best 8567) that Maudave was anxious to meet Voltaire and "take his orders for the Bramins." He did write Voltaire extensively on the "Lingam." Unless there have been other similar letters to the philosopher of Ferney during or right after Maudave's first stay in India, Malesherbes' indication that this is only an extract from a longer letter may very well be confirmed by d'Alembert's statement in another letter to Voltaire (Best. 8458): "He has written you recently a great letter (une grande lettre) on India, which will be for him the best way to commend himself to you." We also know from the unpublished letter that Maudave knew the EzV well, so as to be able to quote from it the relevant passages on the "Lingam." This in turn is confirmed by two marginal notes in what was to become Voltaire's copy of the EzV. Twice on the same folio (fol. 14 recto = book 3, ch. 6), a handwritten note, probably by Maudave to himself, says: "Copy these prayers in the letter to M. de Voltaire." The prayers do not appear in Malesherbes' "extract," but may have figured elsewhere in the letter.

The "extract" raises more questions than it answers. If Maudave was convinced that Martin was the translator of the EzV, and if he wrote so to Voltaire, how do we explain the latter's belief, after he met Maudave in person, that the translator was the high priest "of the island of Cheringam," together with detailed information on this gentleman's knowledge of French and his defense of Law? On the one hand, Maudave assured Voltaire that the translation "was very faithful"; on the other hand, he writes in the letter (9- 10): "I must confess that this manuscript is quite strange. I find in it propositions on the unity of God and on the creation of the universe, which are so direct and so much in agreement with our own Sacred Books, that I cannot have full confidence in the accuracy of the translation."

In fact, Voltaire's general enthusiasm about the French EzV, as described earlier in this volume, is in strange contrast with Maudave's own misgivings. He believes in the antiquity of the Sanskrit language and its EzV, but he does not agree with the way in which the Jesuits interpret -- and translate -- the Vedas. According to them, "the four books of the Vedam contain our principal dogmas and even some of our mysteries." If the Jesuits are right in saying that they have discovered Latin words in the Vedas, the Vedas must be very recent. And this cannot be true. But, then, the Jesuits find traces of their own faith in every part of the world: in the Chinese books, in Mexico, among the savages of South America!

All this seems to indicate at least one thing: Maudave was puzzled by the French EzV, to the point of doubting its authenticity. But he was convinced that it was a translation from a Sanskrit original -- even though elsewhere in the letter (9) he calls it "a Malabar dialogue" --; to him no one must have even hinted at the fact that this might be a text written in French by the missionaries themselves. This leaves us with the question: did Maudave receive a copy of the EzV directly from the Jesuits, or did he obtain it through an intermediary? The sole conceivable argument in favor of the former alternative is Maudave's specific reference to the Jesuits and to the translator, Father Pierre Martin, in his unpublished letter. However, since this letter has remained unknown so far, the latter alternative has been invariably adhered to. Two possible intermediaries have been mentioned over the years.

The first intermediary that has been considered is Maudave's father-in-law, Abraham Pierre Porcher des Oulches, whose name appears repeatedly in the official documents of the French East India Company. He appears as the "chef de la Compagnie" at Masulipatam when his daughter Jeanne Marie was born on 28 October 1736. He was the commander at Karikal, at least from August 1754 until April 1758 and is still so described at the birth of Maudave's daughter Louise Marie Victoire Henriette, on 19 April 1760. Between his posts at Masulipatam and Karikal he was a member of the "Conseil Superieur," and he is again given that title from 6 November 1759 onward.

Porcher des Oulches seems to have taken pride in sending Indian documents to Europe. In his chapter: "On the religion of the Indians," de La Flotte refers to one of his sources as "a manuscript brought from Pondicherry in 1767, and sent through the intervention of Mr. Porcher, the former governor of Karikal. One sees, on one side, the Indian text, and on the other side figures of all the deities painted by a local painter, after the originals which are in de Pagodas." It was once again Porcher's son-in-law, Maudave, who brought these and/or similar documents with him when he returned to France on 9 May 1767. Anquetil, who returned from India on 15 March 1762, appears to refer to the same manuscripts, when he says (1808:3.122n) several years later: "A few years after my return to France, I was consulted about four large volumes in-folio, with figures of Indian deities, accompanied by a French translation, for which he (= Maudave) asked the King's Library a considerable price; the affair was arranged."

Anquetil mentions at least twice the possibility that Maudave obtained the manuscript of the EzV from his father-in-law. But it is clear that, according to him, it is more likely that it came from the papers of Louis Barthelemy. I have already quoted Anquetil's handwritten note to that effect in his own manuscript of the EzV. In a note to Paulinus' Voyage he repeats (1808:3.122n): "The translation of the Ezour-Vedam, made by an interpreter of the Company, passed into the hands of Mr. de Medave (sic), while at the same time another copy remained among the papers of Mr. Barthelemy, which went to his nephew. Father Coeurdoux who, in 1771, mentioned to me the copy of his learned confrere Father Mosac, evidently did not know that the Ezour-Vedam existed in French, in the hands of Mr. Barthelemy; and Mr. de Medave, the purchaser, who wanted the merit of his present for himself, surely did not divulge his acquisition in India. He obtained it either from Mr. Barthelemy himself, or from Mr. Porcher, the commander of Karikal near the famous pagoda of Chalambron, whose daughter he had married."

In fact, at an earlier stage of his career Anquetil mentions (1771:1,1 .lxxxiii) Barthelemy only, and this is also the way in which the origin of the EzV is reported by Sainte-Croix (1778:viii): "This work comes originally from the papers of Mr. Barthelemy, second of the Council of Pondichery. Mr. de Modave, known for his intelligence and for his services, brought a copy of it from India." All this speculation derives, of course, from the way in which Anquetil himself acquired his own copy. As indicated earlier (see p. 8), based on a note in the manuscript, he obtained it, via Court de Gebelin, from Tessier de la Tour, nephew of Barthelemy. He returns to this in his note on Paulinus' Voyage, together with speculations on the origin of the text as translated, in his opinion, by Mosac: "Mr. Barthelemy, second of Pondichery, who was in charge of the interpreters, was a covert Protestant. It is through Mr. Court de Gebelin, also a protestant, that I have been given access to the copy of Mr. Teissier de la Tour, nephew of Mr. Barthelemy. The translation of the Ezour Vedam was sent to the King's library in 1761. Father Mosac, formerly the superior of the Jesuits at Schandernagor, which was taken by the English in 1757, could then very well be at Pondichery. In 1771 Father Coeurdoux mentioned to me that he was the translator of a Vedam in which Indian polytheism is refuted. In view of the precarious situation in which the Mission found itself, he may have tried to show his work to the secretary of the Council at Pondichery, to gain his support. Did Father Coeurdoux know this? Or else, the book may have existed among the Brahmes of Scheringam, who through their contacts with the French undoubtedly became more easy-going in matters of religion."

What was formerly Voltaire's copy of the EzV contains, written by a different hand, a "Notice sur le Zozur Bedo, et sur sa traduction." This notice which, according to a third hand, is "par Mr Court de Gebelin," elaborates in similar terms on the origin of the text. It is, as Pinard de la Boullaye (1922:213n1) rightly remarks, "highly fanciful;" yet, it deserves to be quoted in full in the original for it is also characteristic of Vedic speculations of the time.

[Google Translate from French] "Zozur is a word from the Gentoo languages, and is composed of the word "Zo", against & the word "Zur", poison. This Vedam cannot be better named.

"This Book must have been composed in Malabar. Brama, & the Aughtorrah-Bhade, which is like the Vedam of Malabar, an innovation of the original book, the Shastah of Brama, about 3400 years ago against the doctrines received & expressed themselves on all points of Indian Philosophy and Theology with much freedom and force. Thus the Zozur must be of that time, having been made in the same mind.

As for his Translation, it was made by order of Mr. Barthelemi, First Counselor in Pondicherry. Having a large number of interpreters for him, he had them translate some Indian works with all possible accuracy: but the wars of India & the ruin of Pondicherry led to the loss of everything he had collected on these objects: and only the translation of the Zozur escaped, of which only one complete copy remains in the hands of M. Teissier de la Tour, nephew of M. Constable Barthelemy. probably had no time to finish when M. de Modave embarked to return to Europe."]

I have not been able to gather any information on Tessier -- or Teissier -- de la Tour.

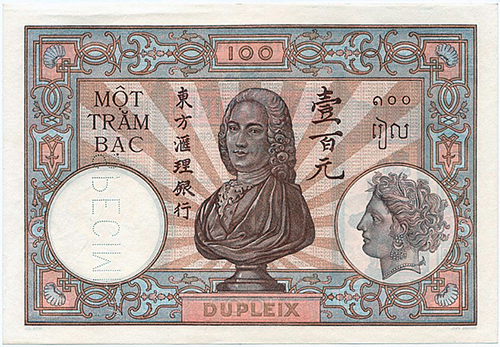

Louis Barthelemy is much better known; although his career in India runs parallel to that of Porcher des Oulches, of the two he is the more prominent one and holds the highest offices. His name appears repeatedly in the official documents of the French Company. He was born at Montpellier, circa 1695, came to India in 1729, and stayed there until his death at Pondicherry, on 29 July 1760. He served at Mahe, was a member of the council at Chandernagore, and was called to Pondicherry in 1742. His duties at Pondicherry were twice interrupted in later years: in 1748 he was appointed governor of Madras, and in 1753-54 he preceded Porcher as commander of Karikal. He rose to the rank of "second du Conseil Superieur," and in the short period in 1755, between the departure of Godeheu and the arrival of de Leyrit, Barthelemy's name appears first on all official documents. It should perhaps be mentioned, first, that on 22 February 1751 Barthelemy represented the father of the bride at the wedding of Jacques Law -- Dupleix was the witness for the bridegroom --, and second, that on 8 August 1758 he was godfather of Jacques Louis Law. These two entries seem to suggest that he was indeed close to the Law family, whose interpreter has been given credit for the translation of the EzV (see p. 28). It should also be pointed out that Barthelemy died more than half a year after Maudave -- and the EzV -- reached Lorient on 2 February 1760.

-- The Ezourvedam Manuscripts, Excerpt from Ezourvedam: A French Veda of the Eighteenth Century, Edited with an Introduction by Ludo Rocher

The Author of the Ezourvedam: Early Speculations

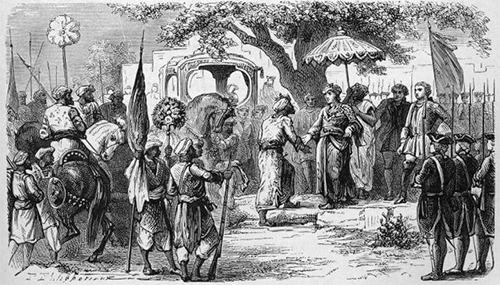

Voltaire obviously did not have a clear idea on the author of the EzV.35 On the one hand he seems to suggest the name of Chumontou; on the other hand he mentions a learned Brahman both as the author of the Sanskrit original and the French translation. Thus, in the Additions a l'essay sur l'histoire generale (1763:18): "I have in hand the translation of one of the most ancient manuscripts in the world; it is not the Vedam which is so much talked about in India but has not yet been communicated to any European scholar; it is the Ezourvedam, an ancient commentary, composed by Chumontou, on this Vedam, on that sacred book of which the Brames say that it has been given to mankind by God himself. This Commentary has been written by a very learned Brame, who has rendered important services to our East-India Company; and he himself has translated it from the sacred Language into French." In the Pricis du siecle de Louis XV Voltaire (1769-1785:25.313; 1774:2.86) refers more specifically to the translator of the EzV. He quotes someone's opinion that the Brahmans "afford the purest model of true piety, which is to be found on the face of the earth," and explains in a note: "The high priest of the island of Cheringam, in the province of Arcate, who justified the Chevalier Law,36 [Jacques Francois Law, who capitulated at Srirangam (12 June 1752). For the ensuing dispute between Law and Dupleix, see Alfred Marthineau: Dupleix et l'Inde Francaise III (1749-1754), Paris: Honore Champion, 1927, pp. 231-60 and passim. Martineau: Dupleix. Sa vie et son oeuvre, Paris: Societe d'Editions geographiques, maritimes et coloniales, 1931, pp. 179-88; Virginia McLean Thompson: Dupleix and his Letters (1742-1754), New York: Robert O. Ballou, 1933, pp. 300-66. It is difficult to verify the source of Voltaire's data: did he have them from Maudave, and, if so, did he reproduce them correctly? I have not been able to find the name of Law's defender. He can hardly be his interpreter Dhosti, since Law pretended that Dupleix and his wife bribed Dhosti to testify against him (Thompson 365).] against the accusations of governor du Pleix [Dupleix], was an old man, aged one hundred years, and respected for his incorruptible virtue; he understood the French language, and was of great service to the East-India Company. It was he that translated the Ezour-Wedam, the manuscript of which I sent to the royal library."

-- Ezourvedam: A French Veda of the Eighteenth Century, Edited with an Introduction by Ludo Rocher

...

What are we to make of this? Today we know, thanks to the efforts of many scholars, that Voltaire's Ezour-vedam was definitely authored by one or several French Jesuits in India, and Ludo Rocher has convincingly argued that the text was never translated from Sanskrit but written in French and then partially translated into Sanskrit (Rocher 1984: 57-60). Consequently, there never was a translator from Sanskrit to French -- which also makes it extremely unlikely that any Brahmin, whether from Benares in the north or Cherignan (Seringham) in the south, ever gave this French manuscript to Maudave. Whether Maudave was "a close friend of one of the principal brahmins" and how old and wise that man was appear equally irrelevant. Voltaire's story of the Brahmin translator appears to be entirely fictional and also squarely contradicts the only relevant independent evidence, Maudave's letter to Voltaire, which (rightly or wrongly; see Chapter 7) named a long-dead French Jesuit as translator and imputed Jesuit tampering with the text. Since it is unlikely that Maudave would arbitrarily change such central elements of his story when he met Voltaire, the inevitable conclusion is that Voltaire created a narrative to serve a particular agenda and changed that story when the need arose.

-- The Birth of Orientalism, by Urs App

John Law de Lauriston

Jean Law's Memoire: Mémoires sur quelques affaires de l’Empire Mogol 1756-1761 contains detailed information about the campaign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and his French allies against the British East India Company.

Jean Law de Lauriston, (born 5 October, 1719 in Paris, died 16 July 1797, in Paris), was a French military commander and colonial official of Scottish origin.[1] He served twice as Governor General of Pondicherry. Not much is known about his life, but his contributions to the French Colonial Empire are notable.

Law was a nephew of the financier John Law, who had founded the Banque Générale and in 1719 had helped re-finance the French Indies companies.[2] He was a contemporary of Alivardi Khan [Aliverdi Khan] who says about him that, "He saw with equal indignation and surprise the progress of the French and the English on the Coromandel Coast as well as in the Deccan."

Law’s son was general and diplomat Jacques Lauriston.

Colonial career

In 1765

When in 1765 the town of Pondicherry was returned to France after a peace treaty with England, Pondicherry was in ruins. Jean Law de Lauriston, then Governor General set to rebuild the town on the old foundations and after five months 200 European and 2000 Tamil houses had been erected.

Transfer of Yanaon

Another significant event in the life of Lauriston was the re-transfer of Yanam to the French. A document dated 15 May 1765 showed that the villages of Yanam and Kapulapalem, with certain other lands, had been ceded by John White Hill and George Dolben. These two were Englishmen acting as agents for Jean Pybus, the head of the English settlement in Masulipatam. They had negotiated a deal (for taking over the villages) with Jean-Jacques Panon, the French Commissioner, who was Jean Law de Lauriston's deputy when he was Governor General of Pondicherry. The 1765 document mentions that France entered into possession of Yanam and its dependent territories with exemption from all export and import duties.

Memoire of 1767

Jean Law de Lauriston wrote Mémoires sur quelques affaires de l’Empire Mogol 1756-1761 which can be found in "Libraires de la Société de l'histoire des colonies françaises" Paris.

He stated in his "Memoire of 1767" as “It is from Yanam that we get out best ‘guiness’ (fine cloth). It is possible to have a commerce here worth more than a million livres per year under circumstances more favorable than those in which we are placed now, but always by giving advances much earlier, which we have never been in a position to do. From this place we also procured teakwood, oils rice and other grains both for the men as well as for the animals. Apart from commerce, Yanam enjoyed another kind of importance. The advantages which may be derived in a time of war from the alliances that we the French may conclude with several Rajas who sooner or later cannot fail to be dissatisfied with the English. Although the English gained an effective control over the Circars, Yanam enabled the French to enter into secret relations with the local chieftains. Yanam had some commercial importance".

Death

He died in Paris on July 16, 1797. There is a village in his name in Puducherry which is still today called as "Lawspet".

His son, Jacques Lauriston, became a general in the French army during the Napoleonic Wars.

References

1. "Jean Law de Lauriston (1719-1797)" (in French). Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

2. William Dalrymple The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of The East India Company, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019, p.48.