The society which rests on modern industry is not accidentally or superficially spectacular, it is fundamentally spectaclist.

-- Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle

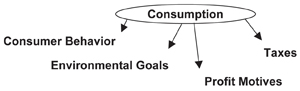

Perhaps it’s all too easy for us to miss the limitations of alternative energy as we drop to our knees at the foot of the clean energy spectacle, gasping in rapture. The spectacle has become a divine deity around which duty-bound citizens gravitate to chant objectives without always reflecting upon fundamental goals. This oracle conveys a ready-made creed of ideals, objectives, and concepts that are convenient to recite. And so these handy notions inevitably become the content of environmental discourse. In a process of self-fashioning, environmentalists offer their arms to the productivist tattoo artist to embroider wind, solar, and biofuels into the subcutaneous flesh of the movement. These novelties come to define what it means to be an environmentalist.1

Environmentalists aren’t the only ones lining up for ink.

Peer pressure is a formidable power, and there’s no reason to assume that rational adults are above its dealings. Every news article, environmental protest, congressional committee hearing, textbook entry, and bumper sticker creates an occasion for the visibility of solar cells, wind power, and other productivist technologies. Numerous actors draw upon these moments of visibility to articulate paths these technologies ought to follow.2

First, diverse groups draw upon flexible clean-energy definitions to attract support. Then they roughly sculpt energy options into more appealing promises—not through experimentation, but by planning, rehearsing, and staging demonstrations. Next, lobbyists, strategic planners, and pr teams transfer the promises into legislative and legal frameworks and eventually into necessities for engineers to pursue. A consequence of this visibility-making is the necessary invisibility of other options. There’s only so much room on the stage.

Productivist Porn

During the rise in oil prices through the first years of the twenty-first century, I remained safely in the library. I studied a corpus of thousands of articles, environmental essays, and political speeches staged around energy through those years.3 I found that most writers fell into a predictable flight pattern, confidently landing their conclusions atop a gleaming airstrip of alternative energy and offering a sense that alternative technologies are all it will take to cure our energy troubles. The way to solve our energy production problems is to produce more energy.

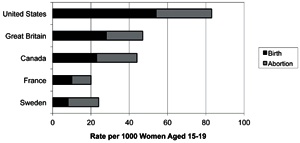

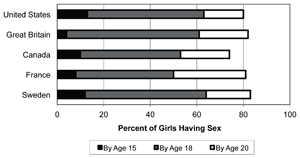

Why do the options of wind, solar, and biofuels flow from our minds so freely as solutions to our various energy dilemmas while conservation and walkable neighborhoods do not? Why do we seem to have a predisposition for preferring production over energy reduction? The answer is neither straightforward nor immediately apparent. Some claim that modern conceptions of prosperity, progress, and vitality structure our preference for production. Evolutionary biologists point to physical characteristics of our brain. Other theorists argue that the productivist spirit rose from Christian values as people abandoned holistic pantheism to worship a creator they understood to be separate from creation. As the natural world was desacralized, it was left exposed to investigation, definition, and scientific manipulation.4

Some intellectuals maintain that the productivist drive should be linked not to Christianity but to philosophical developments in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This is when the mind and body came to be understood as separate, largely due to Descartes’ dualistic view of the self and Kant’s distinction between active subjects and passive natures. Perhaps Newtonian physics also played a role by divesting the material world of spiritual value—depicting it as a gear set devoid of spiritual value— to be sacrificed and exploited without moral consequence. Was it here, nestled in the bosom of the Reformation and scientific achievement, from whence the productivist penchant hath been spawned?5

The genesis of productivism may forever remain a complex mystery. Religious, philosophical, scientific, and capitalist traditions did not develop in separate vacuum chambers, but in orchestration and entanglement with one another.6 Regardless of the particulars of this codevelopment, one outcome is clear. Productivist leanings have effectively nudged nature to the sidelines of Western consciousness. Whether we are considering energy production, human procreation, the work ethic, or any other productivist pursuit, there endures a common theme: that which is produced is good and those who produce should be rewarded. These values till the fertile soil of an almost religious growthism with invasive roots of techno-scientific salvation. 7 Many voices of influence willfully hoist up figures such as Buddha, Jesus, Thoreau, and Gandhi onto pillars, even while trampling over their conceptions of simplicity, humility, community, and service, which they instead characterize as radical and naïve.8

Perhaps these values are naïve when viewed from a hyperindividualist and hyperconsumerist perspective—one where families not only have their own home theater, their own power tools, their own heating system, and their own laundry facilities but have also settled into a concept of living wherein such hyperindependence is normal and unproblematic. Is our perceived independence the residue of the suburban diaspora? Manifest Destiny? Perhaps it arose from the same crib as the productivist spirit. In any case, if we have come to understand the human condition as narrowly arising from the individual, rather than as individuals arising from within the relationships of others, then it demands some attention. For as the poetic philosopher Martin Buber realized, “All real living is meeting.”9 We are born creatures and become human through community.

The Energy Pornographers

We don’t just want our own energy. We want to create it ourselves. It is perhaps not so shocking that President Obama’s opponents mocked him during his initial run for the presidency when he advocated for proper tire inflation in the face of those who were thirsting to drill for oil in the Alaskan wilderness. It is likewise understandable that other politicians, corporations, and many environmental groups steer their platforms away from energy reduction strategies, driving instead toward the glowing symbolism of green energy production. If they include energy reduction strategies in the program, they remain as side acts in the larger alternative-energy big top. Clean energy steals the show. A usa Today journalist goes so far as to claim that alternative- energy production is the only option, insisting that reducing greenhouse-gas emissions “requires” that we immediately deploy “other sources of energy, such as windmills and nuclear plants.”10

Hogwash.

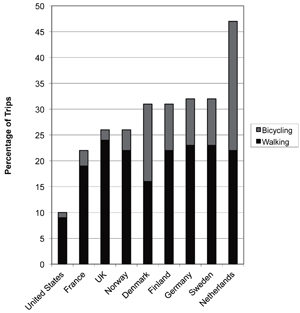

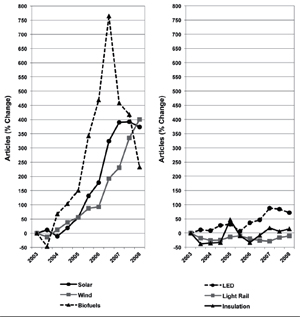

Figure 8: Media activity during oil shock Gas prices more than doubled between 2003 and 2008, but media coverage of solar, wind, and biomass energy shot up faster, averaging a 400 percent increase. Meanwhile, media coverage of energy reduction strategies remained low over the entire period, averaging just a 25 percent increase. (Data from author’s study of fifty thousand articles)

The fact that the national media routinely discharges such gratuitous streams of productivist sewage without objection from environmental groups is a testament to how impoverished environmental movements in the United States have become. As pundits lock their sights on alternative energy, people are not only fooled into ignoring far more promising solutions but also charmed into overlooking how these technologies generate greenhouse-gas emissions, instigate negative side effects of their own, encounter limitations, and most problematically, act to further stimulate overall power demand.

Massive multinational firms control the bulk of media operations. These multinationals own other companies in diverse sectors such as defense, logging, real estate, oil, agriculture, banking, manufacturing, and utilities. Media boards typically reserve spaces at their weighty hardwood tables for these business leaders. Start to see the issue here? These relations assure that the majority of stories, as fair and balanced as they may sometimes seem, are ultimately conceived and developed within the womb of corporate, not public, influence. This may be good, bad, or neutral, depending on your perspective. Regardless, it should hardly come as a surprise that the aggregate of media coverage contains more news segments and articles on alternative-energy technologies, which can be bought and sold, than on conservation and simplicity efforts, which are not as involved in the market mechanism and could in some cases threaten to reduce the very consumption patterns multinationals rely on to achieve quarterly sales forecasts.11

Media industry executives will retort to this accusation with an emphatic, “Squash!” They argue that corporate owners place no pressure on editors to align stories with corporate interests—conglomerates even keep editorial offices separate from their other businesses. But this defense presumes it is possible to maintain a clear separation in the first place. It isn’t. Boardrooms don’t send edicts down to editors—productivist influences on media are typically far more subtle than that. They arise from interstitial forces within the operating procedures of newsrooms themselves. It starts with a tradition that people tend to hold in high esteem: objectivity.

Flirting with Truth

Objectivity in journalism is frequently, yet mistakenly, understood as truth. Facts are slippery things, and news organizations understand that attempting to sell them directly would be sheer folly. Instead, news organizations operate through proxy. Journalistic objectivity is not so much a rendering of truth as much as it is an attempt to accurately convey what others believe to be true. In order to achieve this rendering, experienced journalists instruct young journalists to keep their own beliefs and evaluations to themselves through a conscious depersonalization. Second, mentors instruct them to aim for balance, or field “both sides” of a controversial subject without showing favor to one side or the other. The news industry generally accepts this framework as the best way to go about reporting on issues and events. It’s certainly a lot better than some of the alternatives. Nevertheless, this truth-making strategy carries certain peculiarities.

For example, news editors tend to judge stories supporting the status quo as more neutral than stories challenging it, which they understand as having a point of view, containing bias, or being opinion laden. Investigations that present empirical evidence and consider unfamiliar alternatives are not as valued as the familiar “balance of opinions.” As a result, journalists reduce energy debates to a contest between alternative-energy technologies and conventional fossil fuels. We have all witnessed these pit fights: wind versus coal for electrical production, ethanol versus petroleum for vehicular fuels. Pitting production against production effectively sidelines energy reduction options, as if productivist methods are the only choices available. Have you ever seen news segments that pit solar cells against energy-efficient lighting or that toss biofuels in the ring with walkable communities? Probably not. I have so far come across only a handful of examples out of thousands of reports.

Pitting production versus production seems natural, but it leads to some unintended effects. First, these debates set a low bar for alternative-energy technologies; it’s not difficult to look good when you are being compared to the perfectly dismal practices of mining, distributing, and burning oil, gas, and coal. Imagine if wine critics judged every Bordeaux against a big bottle of acidic vinegar that’s been sitting in grandpa’s cupboard for two decades; it would be difficult for a winemaker to perform poorly in such a contest. Secondly, journalistic dichotomies reduce apparent options to an emaciated choice between Technology A and Technology B. This leaves little space for nontechnical alternatives. It also misses negative effects that both Technologies A and B have in common. Finally, pitting alternative- energy technologies against fossil fuel gives the impression that increasing alternative-energy flows will correspondingly decrease fossil-fuel consumption. It won’t—at least not in America’s current socioeconomic system—as we shall consider in the next chapter.

Implants

Time pressures and streamlining media operations force journalists to increasingly rely on quotes and comments from a short list of contacts, usually government, industry, public figures, or other sources that viewers see as credible. Professor Sharon Beder claims that this “gives powerful people guaranteed access to the media no matter how flimsy their argument or how self-interested.” 12 In the effort to provide credibility, journalists may unknowingly give equal voice to views that are blatantly exaggerated, have already been widely discredited, or are given little credence by those more familiar with the topic.

For instance, in their book Merchants of Doubt, historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway show how over a period spanning decades, oil and industry groups effectively convinced the public that a scientific controversy surrounded climate change when, in fact, there was little disagreement.13 Consensus among climatologists actually began to solidify in the 1970s. In 1988, researchers organized the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to assess the risks associated with human-induced climate change. That same year, NASA reported to Congress that climate change was occurring and that it was caused by humans. After years of research, the IPCC stepped forward to agree with NASA scientists.14

Feeling threatened, several oil companies and other large corporations joined forces to fund advertising campaigns, foundations, and organizations such as the American Enterprise Institute, the Global Climate Coalition, and the George Marshall Institute, in order to attack the credibility of scientists studying climate change and to frame climate change as a scientific “dispute” rather than a consensus. These organizations hired many of the same public relations and legal consultants who had earlier ridiculed doctors for warning about the risks of cigarette smoke.

In the early 1990s, these skeptics organized test markets to ascertain the most effective ways of producing “attitude change.” When they discovered that people tended to believe scientists over politicians or corporations, they test-marketed names of scientific front organizations. Once set up, these front organizations would produce reports that questioned climate change. They distributed their arguments via pamphlets, mass media, and the Internet, rather than publishing in peer-reviewed journals. Internal documents from these organizations reveal that they found radio ads to be the best way to influence “older, less educated males.” For “younger, low-income women,” they selected magazine ads.15 They even test-marketed the spokespeople for their believability. By the early 1990s, these organizations had launched a full-fledged public relations tour to frame climate change as both a controversy and a topic that required more research before consensus could be reached. They ensured that journalists would have ample opportunity to “balance” the views of climatologists with those of the skeptics, even if the naysayers could not speak with scientific authority themselves.

The public relations campaign proved a magnificent success. It swayed public opinion, greatly influenced media coverage, and delayed policy to mitigate the effects of climate change. In 2006, a Time Magazine poll showed that a majority of Americans believed global temperatures were rising. Yet 64 percent also believed that scientists were still busy making up their minds on the matter, when in fact the scientific consensus had already been gathering dust for a decade.16 In 2010 a fox news employee leaked an internal email from the Washington bureau chief that instructed, “Refrain from asserting that the planet has warmed (or cooled) in any given period without immediately pointing out that such theories are based upon data that critics have called into question. It is not our place as journalists to assert such notions as facts, especially as this debate intensifies.”17 By 2012 half of Americans felt climate change probably wasn’t caused by humans and its potential risks were exaggerated.18

Beyond depicting controversy in science where none actually exists (as with smoking and climate change), corporations also use front groups to propose superficial solutions to important problems in order to divert attention away from more serious policy or regulatory changes. For example, a program for the Keep America Beautiful Campaign frames the problem of waste simply as a case of individual irresponsibility. If only people would just be more responsible, they say, perhaps the problem of waste would go away. This frame distracts public attention away from regulatory mechanisms addressing packaging design, recycling, waste legislation, and corporate ethics.19 Similarly, voices for energy reduction strategies are only faintly audible in a room full of deafeningly loud productivists auctioning off their new, refashioned, or camouflaged technological widgets.

Spreading It Mouth-to-Mouth

About twenty years ago, the Pew Research Center found that 33 percent of local journalists felt that business pressures affected their reporting.20 When Pew Research checked in more recently, they found the number had more than doubled to 68 percent. Journalists now cite financial concerns as the foremost challenge facing their craft—more influential than the quality of coverage, loss of credibility, ethics, and concern for standards combined.21

Understaffed news rooms increasingly fall back on source journalism— initiating stories using material distributed by public relations firms and corporations. (This contrasts with the more time-consuming practice of investigative journalism.) Today about half of news stories arise from press releases. This helps explain the nauseating barrage of articles touting new green gadgets, which are simply rewritten press releases from companies promoting their products or researchers eager to attract attention (and funding) for their often half-baked schemes. Readers and viewers have a hard time distinguishing between these rewritten pr scripts and traditional journalism. Reported uncritically and replicated in bulk quantities, these pieces toke news users on the kind of consumerist high typically achieved only through infomercials.22

Commercial news conglomerates aren’t necessarily focused on the public interest as much as on keeping readers and viewers entertained so that they stay tuned for the next round of advertising. Short and exciting stories with captivating visuals attract and hold appropriate audiences for advertisers. Therefore, firms typically provide journalists with videos and computer renderings. The drive for entertainment leaves little space to cover background, contextual fundamentals, or the structural origins of increasing energy consumption. As Robert Pratt from the Kendall Foundation observes, “One of the things that is a difficulty with energy efficiency is that it’s kind of fundamentally boring. Photovoltaic cells, solar cells, or wind turbines are much more interesting to people.”23 It’s perhaps no surprise that this form of journalism generally doesn’t spur minds to engage critically with the social, political, economic, and cultural complexities of our energy system. In fact, a report by the Woodrow Wilson Center contends that people who rely primarily on television for their news are among “the least-informed members of the public.”24

A decade before BP’s Gulf oil spill, the company put these techniques to work in rebranding British Petroleum to “Beyond Petroleum” as it installed solar panels on filling stations throughout the world. The company swamped newsrooms and television stations with press releases, complete with ready-made renderings and photographs of the new panels. BP crafted “Plug into the Sun” promotions to show the greener side of filling stations with copy like, “We can fill you up by sunshine,” even though the gasoline in the pumps was still the same.25 Journalists mechanistically rephrased the press releases, attached the handy visuals, and sent them to press. During the media campaign, journalists rarely offered any context for readers to assess how much solar energy the tiny arrays would produce or how this affected the company’s expanding oil exploitations.

The campaign worked. In fact, out of the collection of articles I studied from this period, I could not find a single one pointing out what might seem an obvious design flaw—some of the solar cells appeared to aim not at the sun, but down toward the asphalt, presumably so incoming drivers could see them as they rolled in. Though perhaps it wasn’t a design “flaw” after all, considering that the company allegedly spent more money on its marketing campaigns than on the solar panels themselves.26

Luckily, some might say, the Internet challenges such greenwashing, as online news sources democratize media and create voices for thousands of niche publications even as traditional journalism declines. At least, that is how the story goes. Unfortunately, the reality is more complicated than this weary story line indicates.27 Despite the many sources of Web-based media, just ten news organizations (which incidentally are associated with legacy media corporations) form an oligarchy attracting most of the eyeballs. Compared with print journalists, Internet journalists are far more likely to indicate that corporate owners and advertisers “have substantial influence on news coverage.” 28 Two-thirds of Internet journalists claim that bottom-line pressures are hurting news coverage as they shift from being reporters to recoders of information.

The ultimate result? Churnalists pump out information on the newest energy gizmos in uncritical articles, which allow us to forget about the complex challenges of our energy systems and instead bask in the warm glow of artificial techno-illumination. As those ideas fade, others will surely show up to warm our hearts soon after. Eight in ten journalists agree. They claim that the scope of news coverage is too narrow and that news rooms dedicate insufficient attention to complex issues such as global energy production, use, and related side effects. When Pew Research asked journalists what media are doing well, just a scant 15 percent pointed to their watchdog role of investigative journalism.29 Media consolidation, with its narrow focus on the bottom line, has fundamentally altered journalistic practice and lubricated passageways for corporate views to slide into the public realm, ensuring that their technophilic, consumerist, and productivist spirit is immediately salient to audiences around the world.30

Power Tools

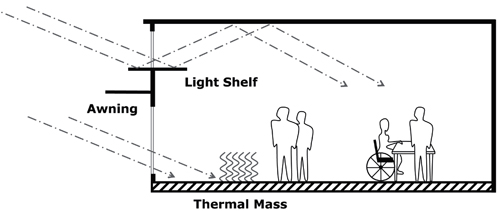

Unsurprisingly, profit motives likely induce much of the gravitational field surrounding productivist energy solutions. For the most part, knowledge elites can patent or otherwise control productivist technologies—manufacturing, marketing, and selling them for a profit (or at least federal handouts). On the other hand, many energy reduction strategies are not patentable because they are based on age-old wisdom and common sense. Solar photovoltaic circuitry, wind turbine modulators, nuclear processes, and even biomass crops are all patentable and commodifiable in a way that passive solar strategies and walkable neighborhoods are not. The profit motive of this ilk is a chronic theme in America; we are a country that values drug research (commodifiable) over preventative health (not commodifiable); most of our soybean fields are planted with corporate- issue genetically modified plants (patentable) rather than seed saved from last year’s crop (not patentable). The debate about whether profits are a noble or a corrupted motivation is a political matter to be argued over a pint of beer, not here in these pages. I aim only to shed the humblest flicker of light on the illusion that the world of alternative energy operates within some virtuous form of economics. It doesn’t. The global economic system rewards the commoditization of knowledge and resources for profit—why would we expect it to be any different for the field of alternative energy?

It’s not just our economic system that offers virulence to our productivist inclinations; our political system does as well. The politics of production are far more palatable than the politics of restraint, as President Jimmy Carter learned in the 1970s. When he asked Americans to turn down the thermostat and put on a sweater, he received a boost in the polls. But voters ultimately turned to label him a pedantic president of limits. “No one has yet won an election in the United States by lecturing Americans about limits, even if common sense suggests such homilies may be overdue,” remarks historian Simon Schama. “Each time the United States has experienced an unaccustomed sense of claustrophobia, new versions of frontier reinvigoration have been sold to the electors as national tonic.”31

Clean energy is the tonic of choice for the discerning environmentalist. Over recent decades, flows of power within America and other parts of the world began pooling around alternative-energy technologies. Mainstream environmental organizations took a technological turn, which gained momentum during the 1970s and became especially palpable in the 1980s when the Brundtland Commission brought the idea of sustainable development into the spotlight. The commission passed over societal programs to instead underline technology as the central focus of sustainable development policy.32 The commission’s 1987 report, Our Common Future, stated, “New and emerging technologies offer enormous opportunities for raising productivity and living standards, for improving health, and for conserving the natural resource base.”33 This faith in the ability of technologies to deliver sustainable forms of development evolved during a period of public euphoria surrounding information technology, agricultural efficiency through petrochemicals, management technology, and genetic engineering. As in other periods throughout American history, there was a sense that if nature came up short, the wellspring of good ol’ American know-how would take up the slack.34

Mainstream environmental organizations were all too eager to fill the pews of this newly energized church of technological sustainability, which they themselves had helped to consecrate. For instance, a World Resources Institute publication declared in 1991, “Technological change has contributed most to the expansion of wealth and productivity. Properly channeled, it could hold the key to environmental sustainability as well.”35 The next year the United Nations developed a sustainable development action plan called Agenda 21, which charged technological development with alleviating harmful impacts of growth. As the new centerpiece of social policy, there was little debate around technology, other than how to implement it. During the 1980s and ’90s, environmental organizations began to disengage from the dominant 1960s ideals, which centered on the earth’s limits to growth. They shifted to embrace technological interventions that might act to continually push such limits back, making room for so-called sustainable development. The former enthusiasm for stringent government regulation waned as environmental organizations expanded the roles for “corporate responsibility” and “voluntary restrictions.” As a result, legislators pushed aside public environmental stewardship and filled the gap with corporate techniques such as triple-bottomline accounting and closed-loop production systems, which purported to be good for the environment and good for profits.36 In 2002, breaking with past mandates, the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development’s Plan of Implementation narrowed its assessments by assuming that technological sustainability would require “little if any political and cultural negotiation about modern lifestyles, or about the global systems of production, information, and finance on which they rest.”37 And by 2004, Australia Research Council Fellow Aidan Davison observed that “the instrumentalist representation of technologies as unquestioned loyal servants” had come to fully dominate sustainable development policy.38

The so-called limits-to-growth theories of the 1960s certainly had limits of their own as effective conceptual tools for change. Yet the mass exodus away from these guiding concepts and toward an overwhelming reliance on technological fixes may have overshot the realm of reasoned and vital inquiry into the diverse causes of our unsustainable energy system. It has also erected a formidable fortress of interests.

Objects of Affection

Solar power means different things to different people, yet the notion’s heartiness manages to sustain a common identity across various disciplines. Solar cells are “boundary objects,” described by Susan Leigh Star and Jim Griesemer as concepts “both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and the constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites.” These objects of affection “have different meanings in different social worlds but their structure is common enough to more than one world to make them recognizable, a means of translation.”39 While it may seem peculiar to categorize solar power as a translator, it can certainly be understood as serving this function.40 Beyond its obvious service in producing electrical power, solar power plays less apparent social roles in politics, industry, academia, and in the public sphere where various groups employ solar for their own purposes. Let’s consider an example.

If solar energy were a puppy, it would be a super cute little tike—a happy puppy trotting along with all of society’s dog walkers. The academic dog walker likes Solar because walks with Solar bring benefits such as recognition and grant money. Industry likes walking Solar because it offers tax breaks, production opportunities, and good public relations for the company. Government enjoys being out with Solar as well. The public sees Government in a good light for walking Solar. And when elections come around, all the more reason to take Solar out for a stroll! Media likes Solar too—Solar offers exciting graphics, news stories, and segments people will watch, which brings in more advertising dollars. Public is always out on the walks; Solar makes Public feel happy, responsible, and successful in combating environmental challenges. Sometimes, being just a puppy, Solar gets tired, but there is always someone around to pick Solar up and keep going.

On walks with Solar, the various dog walkers all get along fairly well. Occasionally, they even release Solar from the leash to run ahead—“Go get ’em, Solar, go on!” Their interests in a healthy and happy Solar generally run in parallel or complement one another, making these walks a friendly outing even if they often just go to the park and walk in circles.

Now let’s consider the walk with Energy Reduction. Reduction is a huge dog with lots of potential, though walks with Reduction differ from walks with Solar. Reduction’s walks include many more stops to pee. Academia likes Reduction and gets some government funding for going on these walks. Industry, on the other hand, sees Reduction as more of a nuisance, sometimes saving some money, but more often getting caught up in regulations along the way, bringing the walk to a stop at times. Usually, there is some bickering between Industry and Government, but they usually work things out since Government doesn’t have much to gain; Government’s constituents don’t pay much attention to Reduction. Media finds the walks with Reduction to be tiresome—not much new news here. Public agrees, seeing walks with Reduction as a decrease in living standards. Why go for a walk with Reduction, when the walks with Solar are so much more fun?

Poor Reduction doesn’t get taken out for walks nearly as much as is healthy for a dog of Reduction’s size and age. The dog walkers seem, at best, ambivalent, and at worst, plainly disgruntled. As policymakers, students, environmentalists, and concerned citizens, we need to understand how to organize walks with Reduction that interest more of the dog walkers. We’ll come to that challenge in the next chapter.

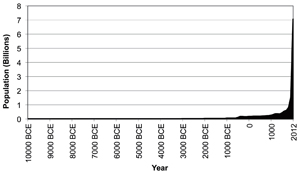

Erecting the Clean-Energy Spectacle

Since progrowth ideals are well-funded, politically powerful, connected with media, and pervasive in public thought, it’s no surprise that most of us have come to accept many progrowth premises as self-evident truth. Together they form a formidable force within local and international polity and economy. We expect companies to increase their earnings, labor to expand, and material wealth to increase throughout the world until every last child is fed, clothed, educated, and prosperous. This story line is conceivable only if we are willing to delude ourselves into believing there are enough resources on the planet for many more inhabitants of the future to consume, eat, play, and work at the standards that wealthy citizens enjoy. I’ve come across little convincing research to support the possibility that this is physically viable today, let alone in a more heavily populated and resource- depleted planet of the future.41

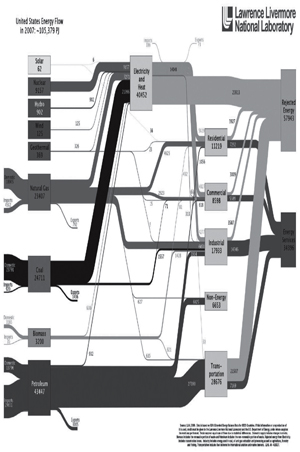

These progrowth ideals act to structure future energy investments. For instance, the International Energy Agency (IEA), as do other governmental agencies, crafts long-term predictions of world energy use, primarily extrapolating from past trends in population growth, consumption, efficiency, and other factors. Subsequently, large energy firms evoke these predictions in their business plans in efforts to prod governments and investors to support drilling, exploration, pipeline construction, and other productivist undertakings. Alternative-energy companies have historically done the same. Once firms translate these predictions into investment, and investment into new energy supply, energy becomes more affordable and available. Energy consumption increases and the original predictions come true.

Numerous actors and factors hold the self-fulfilling prophecy together. Powerful energy lobbies promote their productivist inclinations in the halls of government. Industry and a consumer-driven public sop up any excess supply with a corresponding increase in demand.42 And since side effects are often hidden or displaced, the beneficiaries can continue at the expense of others who are less politically powerful, or who have not yet been born. For all practical purposes these side effects must remain hidden in order for the process to continue.43

Experts have developed a language to determine what is counted and what is not.44 For instance, an influential congressional report from the National Research Council, entitled The Hidden Costs of Energy, explicates numerous disadvantages, limitations, and side effects of energy production and use. But it specifically excludes some of the most horrible of these—including deaths and injuries from energy-related activities as well as food price increases stemming from biofuel production.45 The authors dedicate several pages and even a clumsy appendix to convincing readers that such factors needn’t be interrogated because they don’t meet the economic definition of “externalities.” Here their tightly scripted definition comes to run the show. It stands in for human judgment to decide what gets counted and what doesn’t. Within this code, a whole world of side effects needn’t be interrogated if they don’t fit neatly within the confines of a definition.46 In a moment of trained incapacity, the authors miss that it’s the definition itself that requires interrogation.47 It’s not particularly shocking that this could happen in a formal policy report. It happens all the time. What’s shocking is that a report featuring such glaring omissions could attract the signoff of over one hundred of the nation’s most influential scientific advisers. There are some oversights it takes a PhD to make.48

Since we live on a finite planet with finite resources, the system of ever-increasing expectations, translated into ever-increasing demand, and resulting in again increased expectations will someday come to an end, at least within the physical rules of the natural world as we understand them. Whether that end is due to an intervention in the cycle that humanity plans and executes or a more unpredictable and perhaps cataclysmic end that comes unexpectedly in the night is a decision that may ultimately be made by the generations of people alive today.

Perhaps we should find the courage to do more than simply extrapolate recent trends into the future and instead develop predictions for a future we would like to inhabit. These are, after all, the aspirations that will become the basis for policy, investment, technological development, and ultimately the future state of the planet and its occupants.49

The immediate problem, it seems, is not that we will run out of fossil-fuel sources any time soon, but that the places we tap for these resources—tar sands, deep seabeds, and wildlife preserves— will constitute a much dirtier, more unstable, and far more expensive portfolio of fossil-fuel choices in the future. Certainly alternative-energy technologies seem an alluring solution to this challenge. Set against the backdrop of a clear blue sky, alternative-energy technologies shimmer with hope for a cleaner, better future. Understandably, we like that. Alternative-energy technologies are already generating a small, yet enticing, impact on our energy system, making it easier for us to envision solar-powered transporters flying around gleaming spires of the future metropolis. And while this is a pristine and alluring vision, the sad fact is that alternative-energy technologies have no such great potential within the context that Americans have created for them. An impact, yes, perhaps even a meaningful one someday in an alternate milieu. However, little convincing evidence supports the fantasy that alternative-energy technologies could equitably fulfill our current energy consumption, let alone an even larger human population living at higher standards of living.

This isn’t to say there aren’t solutions. There are. We’ve just been looking for them in the wrong place.