by Hannah Phillips

Palm Beach Post

Published: 1:47 p.m. ET Jan 8, 2024 Updated 2:24 p.m. ET Jan. 9, 2024

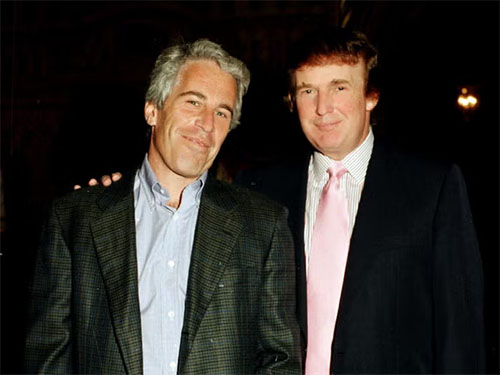

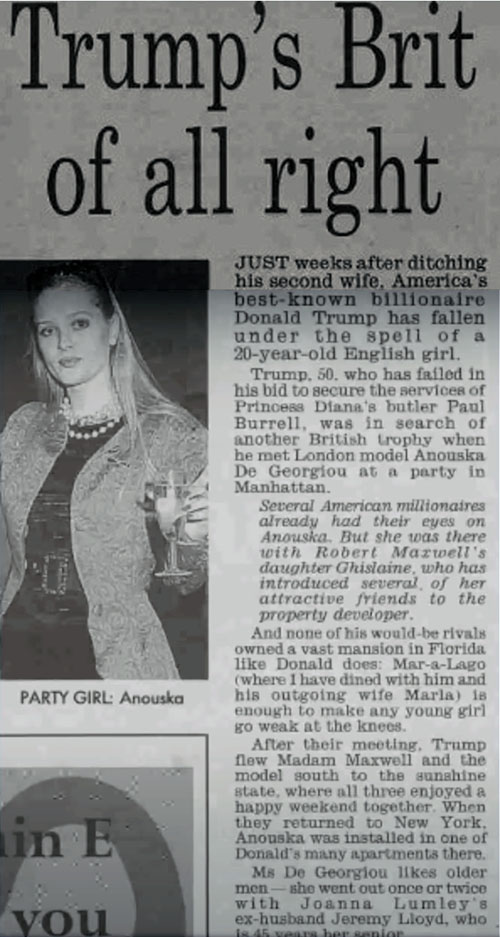

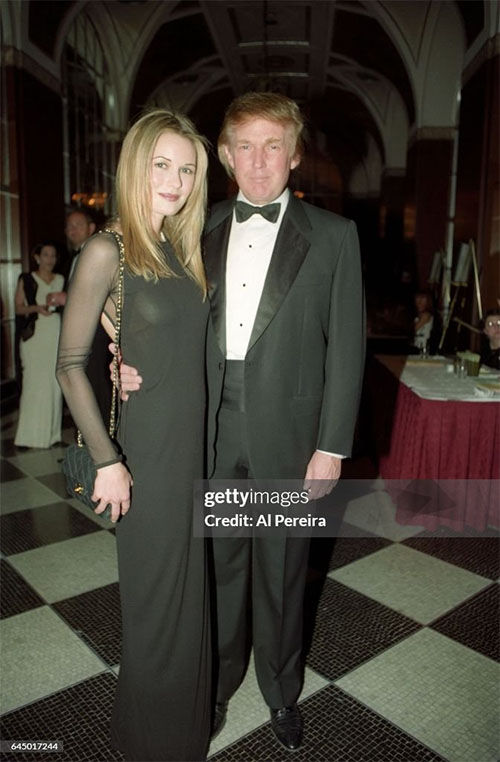

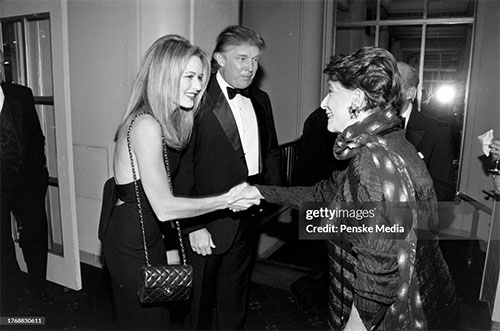

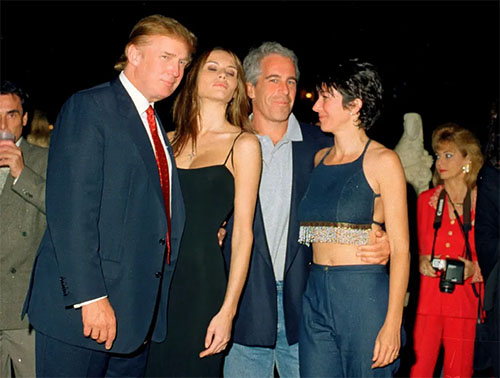

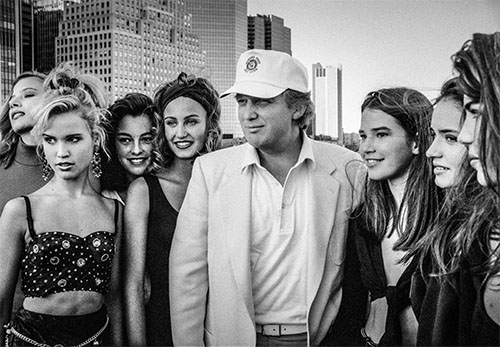

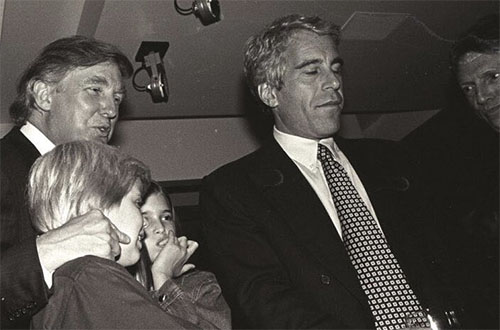

In the latest batch of Jeffrey Epstein documents, a woman claims that Donald Trump had sex with "many women" in Epstein's New York mansion. It's one of several bombshell allegations made by Epstein victim Sarah — some of which she later retracted out of concern for her family's wellbeing.

The allegations appear in a trove of documents a federal judge has steadily released since Jan. 3, which detail the breadth and depth of a the sex trafficking ring Epstein operated from his Palm Beach mansion and beyond.

The latest batch of documents includes a sampling of emails Ransome sent to a New York Post reporter in 2016 linking former presidents Trump and Bill Clinton to Epstein's "seedy inner circle." Ransome claimed that Epstein recorded sex tapes of Clinton, Prince Andrew and other prominent men to keep as blackmail, though no such footage has ever been publicly uncovered.

Ransome also said that an unnamed friend who allegedly had sex on separate occasions with Clinton and the Duke of York "was made to feel like a dirty whore and a liar" when she reported it to police in 2008.

According to Ransome, her friend was approached months later "by Special Agents Forces Men sent directly by Hilary (sic) Clinton herself, in order to protect her presidential campaign in 2008."

As Clinton had hinted in his 1987 withdrawal, he and Hillary had already begun to formulate the tactics they would adopt to deal with the all too real potential for a sex scandal's erupting during a presidential campaign. He had thought it a "weakness" in Hart, aides remembered, that the senator seemed to equivocate over issues like a definition of adultery and appeared unprepared to lash back to discredit the attacks. Hart, who had formally and openly separated from his wife in 1979 and again in 1981, would admit to having seen women during the separations but otherwise refused to answer questions about infidelity. At the same time, no woman had come forward to accuse him, including Donna Rice.

With Hart's precedent and four years to prepare, Clinton's response would be more concerted and sophisticated, at least as staff and advisers saw it evolve between 1987 and the 1992 race. He might acknowledge having had "difficulties" in his marriage -- "nodding humbly at the weakness of the flesh," as a Hot Springs friend put it caustically, "like a good Southern Baptist is supposed to do" -- but dismiss them as all in the past. Unlike what they saw as a passive Lee Hart, Hillary would stand behind him with characteristic firmness. "She was never to play the poor little wife," said one adviser. They would also be prepared to strike back at any women accusers -- "taking on the bitches," as one former staff member put it -- including with private campaigns of "spin" to discredit them with the media and even pressures to silence them. Above all, however, Clinton would simply deny everything. Barring the most direct evidence -- which advisers and others say he always assumed would never be available -- he was sure the story could go no further. The governor, they remembered, had an almost mystical faith in the absence of photographs. "He felt it was probably those pictures that killed Hart, that and being sort of mealy-mouthed about the whole thing," one friend remembered. "If you could deny it over and over, the reporters would get tired sooner or later and go away to something else." As Clinton himself would tell one of the women, Gennifer Flowers, late in 1991, "If they ever hit you with it, just say no and go on. There's nothing they can do .... If everybody kinda hangs tough, they're just not going to do anything. They can't ... if they don't have pictures."

Even given all the familiar reasons for discretion and concealment by the women themselves, there was no small potential for revelation. There had been far too many cases. As they eventually told their stories after he was elected president, the Arkansas trooper bodyguards and others would testify to Bill Clinton's extramarital relations with literally hundreds of women, "There would hardly be an opportunity he would let slip to have sex," a state police security guard told the London Sunday Times in 1994. Insistent denials by both Clinton and the woman in question would not always be a guarantee of erasing suspicion, even without photos. While one woman employee of an Arkansas utility continued to deny any relationship with the governor, for example, the Los Angeles Times unearthed partial phone records between 1989 and 1991 that showed Clinton telephoning her fifty-nine times at her home and office, placing eleven cellular calls to her residence on July 16, 1989, and, two months later, while on an official trip, making a ninety-four-minute call at 1:23 a.m. and another for eighteen minutes the next morning at 7:45. Clinton had been wrong when he talked about telephone evidence in a tape-recorded conversation with Gennifer Flowers in December 1991. Did she have phone records? he had asked her after she told him someone had broken into her apartment. "Unh unh. I mean why would I? You ... you usually call me, for that matter. And besides, who would know?" Flowers had answered. And Clinton, speaking from the mansion, had seemed to reassure himself: "Isn't that amazing? Well . . . I wouldn't care if they ... you know, I, I ... They may have my phone records on this computer here, but I don't think it.... That doesn't prove anything."

Though most of the eyewitness accounts would appear only after the 1992 election, the list of the future president's illicit affairs would be remarkably detailed, including more than twenty women who stepped forward or were otherwise publicly identified by the spring of 1994. Troopers would describe the wife of a prominent local judge, a Little Rock reporter, a former state employee, a cosmetics clerk at a Little Rock department store, and several others, including Flowers, whom Clinton had seen at intervals of two to three times a week in the course of relationships lasting anywhere from weeks to months to years. According to the British press, there had been a black woman who claimed, after more than a dozen visits by the future president, that Clinton was the father of her child. In the testimony, too, were the settings and circumstances -- the flaunting of girlfriends in public, Clinton's slipping troopers cash to pay for gifts at Victoria's Secret in Little Rock's University Mall, the constant and often vain efforts to conceal movements from Hillary and the periodic scenes between Clinton and her, the numberless one-night stands with strangers in the state and beyond, oral sex in the dark parking lot of Chelsea's elementary school. "Later he told me that he had researched the subject in the Bible," trooper Larry Patterson told the American Spectator, "and oral sex isn't considered adultery." Some thought it all undeniably pathological. "What has emerged," Geordie Greig of the London Sunday Times wrote, "is a man with what would appear to be an almost psychotic inability to control his zipper."

From the first alarm and strategizing after the Hart episode in 1987, the response of the Clinton entourage had been to view the womanizing in an almost prudish way, fearing outright public rejection. "We were thinking how it was going to play in Jonesboro or Paragould," said one aide, "and of course we were thinking of Gary Hart." But the national public response in 1992 would prove apparently more lenient and worldly. When audiences in New Hampshire, New York, or California seemed ready to accept that a presidential candidate's private life -- whatever his extramarital sexual habits and whether they credited his denials or not -- had no bearing on his integrity as a leader, Clinton's aides regarded their strategy of simply stonewalling as vindicated. Neither then nor later did many of those around Clinton reflect on the deeper meaning of the womanizing and what it said about other aspects of the man and leader.

At almost every turn in the history was an abuse of power and trust: the routine employment of the troopers to facilitate, stand guard, and cover up; the use of state cars and time and the sheer good name and prestige of the governor's office.

It was not that Clinton had governed and then made his sexual forays as part of some scrupulously separate private life. In part because of the furtive shadow play with Hillary, in part the product of his own insouciance and sense of entitlement, much of the philandering took place during the workday, on official trips, or around ceremonial or political functions. He had indulged a good deal of his relentless promiscuity as the government. Propositioning young women at county fairs or enticing state employees at conferences, he enjoyed much of his predatory privilege because he was the government.

There was also the issue of how much the illicit practices opened the governor and future president to blackmail or how much the gifts and other expenses, which could not be taken from any legitimate income that Hillary might notice, made him all the more dependent on his own "walking around" cash from backers. Equally telling was what it all revealed about his genuine attitude toward women. The repeated testimony of the troopers would show the undisguised Clinton rating women as objects, "ripe peaches," as he called them, "purely to be graded, purely to be chased, dominated, conquered," according to L.D. Brown. The governor had been predatory even toward one of the trooper's wives and toward another's mother-in-law.

There was a sharp demarcation between his two worlds, the public champion of equal rights naming women to high office and the seducer who preferred his partners without too much rival seriousness, rewarding substance only as part of the seduction. A young staff analyst for the National Governors' Association would remember Clinton's courting her not only by personal charm and flirtation but also by ardent support of her policy proposals. When she firmly rebuffed his advances one night at an NGA dance, however, he instantly lost interest in her ideas -- "cut me and the policies dead the next day," she remembered. When a former Miss Arkansas, Sally Perdue, told of a four-month affair with Clinton that began not long after he returned to power in 1983, reports fixed on her colorful details of the governor parading around her apartment in one of her black nightgowns playing his saxophone, using cocaine. More significant were the circumstances of their breakup. When she told him she was thinking of running for mayor of Pine Bluff, Clinton bristled. "You'd -- you'd better not run for mayor," he warned her, and the relationship ended in an angry argument. He was clearly upset that she had crossed a line, Perdue remembered. A "good ole boy," as she recalled him, he had wanted a "good little girl" as an intimate. "I don't think he really wanted me to be an independent thinker at that point," Perdue would say.

Fear of exposure notwithstanding, the behavior would continue through the election and transition. Among the troopers' stories would be a scene at the Little Rock airport as the president-elect and his wife left for Virginia and their inaugural procession into Washington. Hillary noticed a security guard escorting one of the women to the farewell ceremony and turned on him angrily. "What the fuck do you think you're doing?" she asked Larry Patterson, according to his account in the American Spectator. "I know who that whore is. I know what she's doing here. Get her out of here." In a reaction familiar to many aides, Clinton simply shrugged and the trooper took the woman back to the city. At the same juncture, having witnessed during the later days of the campaign and during the transition what some in Arkansas had seen for years, even the legendarily discreet Secret Service was shocked by the new occupants of the White House. According to reliable sources, some of the agents who had been in Little Rock filed an extraordinary warning with headquarters referring in old-fashioned terms to issues of "moral turpitude" involving the president-elect.

Even after the troopers' initial revelations in the Los Angeles Times and the American Spectator late in 1993, however, the issue would be all but marginalized by the mainstream media. ''I'm not interested in Bill Clinton's sex life as governor of Arkansas," New York Times Washington bureau chief R.W. Apple told a British reporter. At the same time, longtime Washington Post journalist Mike Isikoff would find himself in a shouting match with editors who were refusing to publish even a portion of his meticulously researched investigative report on Paula Jones, who would later bring a sexual harassment lawsuit against the president. Jones's much-substantiated story of being propositioned by Clinton at the Excelsior Hotel in Little Rock on May 8, 1991, when she was a twenty-four-year-old Arkansas state employee, was typical of the situation in which many young women of her time and class found themselves during the Clinton era. Yet few episodes so starkly expressed the inherent sexism, class discrimination, and willful myopia of the Washington establishment as the Jones case. The media, national women's organizations, leaders throughout the Congress, and organized labor and other ostensibly progressive institutions alternately ignored, dismissed, or even belittled Jones and witnesses like her. The studied hypocrisy and insensitivity to the underlying issues of abuse of power and exploitation of women would be one more vivid example of the capital's culture of complicity.....

Much of the rest of the campaign would be directed not at making a point of his power and willingness to use it but at hiding its embarrassments. The Clintons summoned Betsey Wright to brief reporters on local Arkansas critics and seemingly trivial local issues and incidents. "I'll swear to God there were dossiers kept on anybody who said anything crossways of Clinton, and I don't know who did it, but a lot of folks got smeared real good with the reporters," said one Little Rock activist. "You'd talk to a reporter and they'd be ready to jump on a story and look into everything," remembered another, "and then they'd go down to [Clinton campaign] headquarters and come out thinking you ought to be in a straitjacket or jail or you were just dumb or vengeful. When they got through attacking people personally down there, it wasn't just the people who suffered, but real issues like Whitewater or funny money didn't have any credibility either." "Where's the info on Gennifer?" Hillary Clinton had asked Little Rock from a pay phone on the campaign trail when the story broke. The tactics of suppression were not limited to Arkansas, however, and were not always so genteel as providing discrediting information or spin for visiting reporters. The campaign soon hired a private detective to work on the "bimbo problem." Then, too, Sally Perdue would later tell of being approached by a Democratic functionary in Illinois and none too subtly warned that she might have her knees broken or worse if she continued to speak publicly about her relationship with Clinton. For their part, the professionals of the campaign would deny any knowledge of such practices, though Betsey Wright, gone to a lobbying job in Washington, would be enlisted again in 1994 and afterward to "explain" the instability or seamy motives of those, like the state troopers, who told their stories. It would be a mark of the Clinton White House to attack in open and secret the people who exposed its inhabitants and thus to evade, often successfully, the substance and truth of the charges, the issues themselves.

-- Partners in POWER: The Clintons and Their America, by Roger Morris

President Bill Clinton assaulted me in the Oval Office.

I went through intensive FBI interrogations, gave depositions, and testified before the grand jury. In the process, I hurt Clinton. His machine came after me and defamed me in the media. They coerced others to lie about me. They violated my right to privacy. I suffered a public ordeal of humiliation and frustration. That was the fight that the American public saw.

But there was another side of my ordeal. It was the private side -- my private terror.

They threatened my children. They threatened my friend's children. They took one of my cats and killed another. They left a skull on my porch. They told me I was in danger. They followed me. They vandalized my car. They tried to retrieve my dogs from a kennel. They hid under my deck in the middle of the night. They subjected me to a campaign of fear and intimidation, trying to silence me. It didn't work.

When Bill Clinton assaulted me, he betrayed my trust and our friendship. This was a personal betrayal. But that which followed was not. That which followed was a betrayal of the public trust, of political power, and of the Democratic ideology that the Clintons and I once held dear. Subjected to sexual abuse at the hands of Bill Clinton, I was then subjected to abuse of power at the hands of the Clinton administration. More than any other's, these were Hillary Clinton's hands.

When the White House released letters in which I asked President Clinton to help me find a government job, they broke the law and violated my right to privacy. That was Hillary's call. When my corroborating witness recanted her story, a very powerful Washington lawyer whom she could ill afford stepped in to represent her. That was Hillary's good friend. When a White House aide predicted my reputation would sink just days after my first public appearance, he told a friend he could go to jail for what he was doing. That was Hillary's aide. When White House lawyers hired private investigators, those thugs terrorized me. They were Hillary's investigators.

-- Target: Caught in the Crosshairs of Bill and Hillary Clinton, by Kathleen Willey

-- Passion and Betrayal, by Gennifer Flowers with Jacquelyn Dapper

-- Target: Caught in the Crosshairs of Bill and Hillary Clinton, by Kathleen Willey

-- Partners in POWER: The Clintons and Their America, by Roger Morris

-- The Secret Life of Bill Clinton: The Unreported Stories, by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

-- Compromised: Clinton, Bush and the CIA: How the Presidency was Co-opted by the CIA, by Terry Reed & John Cummings

Sarah Ransome

Victim retracts claims, cites concerns for family

The same batch of documents contains another email in which Ransome retracted her claims, telling the reporter she feared for her family's safety and wanted "to walk away from this." She told Bazaar in 2021 that Epstein threatened to murder her family if she spoke publicly.

"It's not worth coming forward," she wrote. "I will never be heard anyhow."

In a 2019 New Yorker article, Ransome added that she "had invented the tapes to draw attention to Epstein’s behavior, and to make him believe that she had ‘evidence that would come out if he harmed me.’”

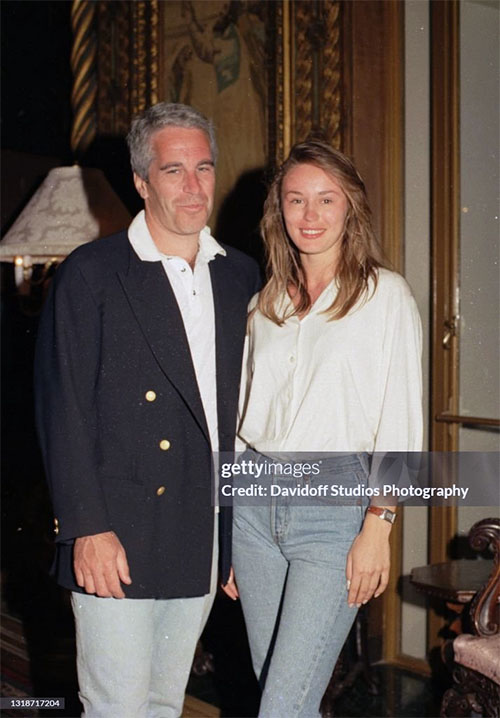

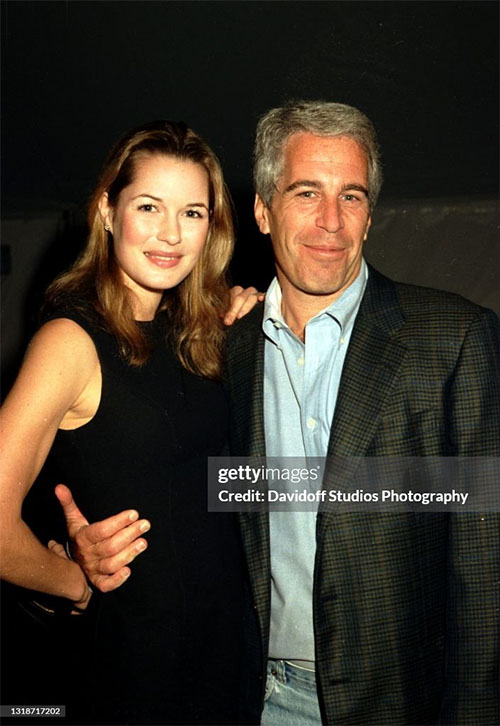

Ransome said she met Epstein in 2006 and was raped and starved in the year she spent in his circle of women and underage girls. In a deposition, Ransome said she wanted to expose Epstein to stop him from hurting others.

"Seeing as I’m going to be a parent myself, I can’t really live with myself knowing that there’s a pedophile with my kids on the planet," she said. "So as a responsible human being, I thought that I would come forward."

Attorneys representing Alan Dershowitz — who Ransome has also accused of sexual abuse — submitted her emails to the court in an attempt to undermine her credibility.

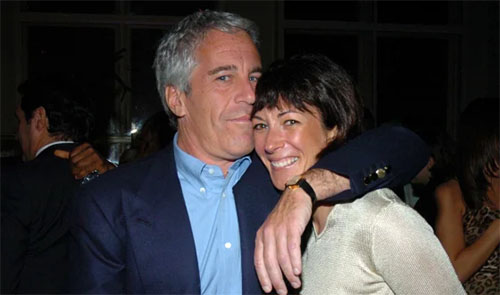

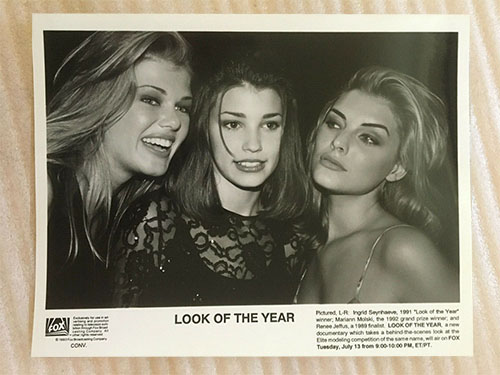

Monday's documents are among the last expected to be unsealed in victim Virginia Giuffre's defamation lawsuit against Ghislaine Maxwell. Giuffre, who in 2001 worked as a teenaged spa attendant at Mar-a-Lago, said Epstein forced her to have sex with Prince Andrew and other prominent men after Maxwell lured her into his circle.

Maxwell called the accusations lies, prompting Giuffre to sue in 2015. Though the case was settled and sealed two years later, the Miami Herald successfully fought to have the names and documents associated with it made public.

Maxwell is serving a 20-year sentence at a Tallahassee prison — where she teaches etiquette to fellow inmates — for helping Epstein sexually abuse underage girls. Epstein pleaded guilty to two state prostitution-related charges in 2008 and served 13 months in a work-release program at the Palm Beach County Jail.

Federal prosecutors in New York charged Epstein with sex trafficking in July 2019. He was found hanged in his jail cell less than a month after his arrest.

Hannah Phillips covers criminal justice at The Palm Beach Post. You can reach her at [email protected]. Help support our journalism and subscribe today.