Part 2 of 2

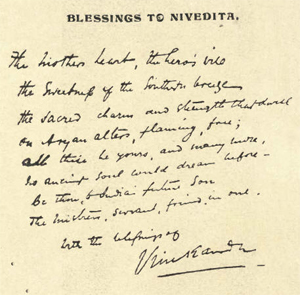

Process philosophy and theology Philosopher Nicholas Rescher. Rescher is a proponent of both Whiteheadian process philosophy and American pragmatism.

Philosopher Nicholas Rescher. Rescher is a proponent of both Whiteheadian process philosophy and American pragmatism.Historically Whitehead's work has been most influential in the field of American progressive theology.[124][138] The most important early proponent of Whitehead's thought in a theological context was Charles Hartshorne, who spent a semester at Harvard as Whitehead's teaching assistant in 1925, and is widely credited with developing Whitehead's process philosophy into a full-blown process theology.[147] Other notable process theologians include John B. Cobb, David Ray Griffin, Marjorie Hewitt Suchocki, C. Robert Mesle, Roland Faber, and Catherine Keller.

Process theology typically stresses God's relational nature. Rather than seeing God as impassive or emotionless, process theologians view God as "the fellow sufferer who understands", and as the being who is supremely affected by temporal events.[148] Hartshorne points out that people would not praise a human ruler who was unaffected by either the joys or sorrows of his followers – so why would this be a praise-worthy quality in God?[149] Instead, as the being who is most affected by the world, God is the being who can most appropriately respond to the world. However, process theology has been formulated in a wide variety of ways. C. Robert Mesle, for instance, advocates a "process naturalism", i.e. a process theology without God.[150]

In fact, process theology is difficult to define because process theologians are so diverse and transdisciplinary in their views and interests. John B. Cobb is a process theologian who has also written books on biology and economics. Roland Faber and Catherine Keller integrate Whitehead with poststructuralist, postcolonialist, and feminist theory. Charles Birch was both a theologian and a geneticist. Franklin I. Gamwell writes on theology and political theory. In Syntheism - Creating God in The Internet Age, futurologists Alexander Bard and Jan Söderqvist repeatedly credit Whitehead for the process theology they see rising out of the participatory culture expected to dominate the digital era.

Process philosophy is even more difficult to pin down than process theology. In practice, the two fields cannot be neatly separated. The 32-volume State University of New York series in constructive postmodern thought edited by process philosopher and theologian David Ray Griffin displays the range of areas in which different process philosophers work, including physics, ecology, medicine, public policy, nonviolence, politics, and psychology.[151]

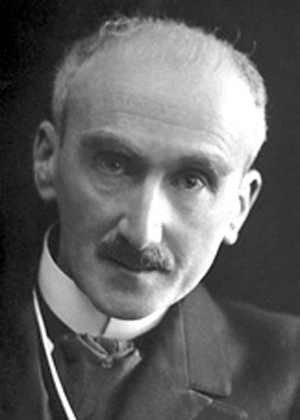

One philosophical school which has historically had a close relationship with process philosophy is American pragmatism. Whitehead himself thought highly of William James and John Dewey, and acknowledged his indebtedness to them in the preface to Process and Reality.[3] Charles Hartshorne (along with Paul Weiss) edited the collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, one of the founders of pragmatism. Noted neopragmatist Richard Rorty was in turn a student of Hartshorne.[152] Today, Nicholas Rescher is one example of a philosopher who advocates both process philosophy and pragmatism.

In addition, while they might not properly be called process philosophers, Whitehead has been influential in the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze, Milič Čapek, Isabelle Stengers, Bruno Latour, Susanne Langer, and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.[citation needed]

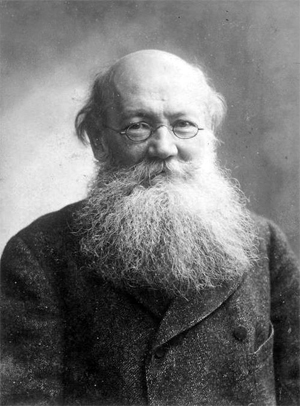

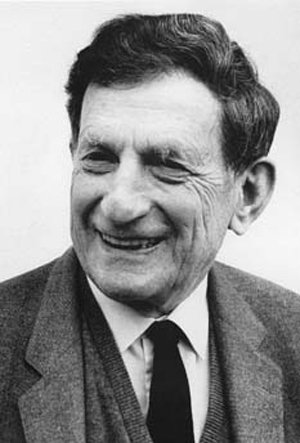

Science Theoretical physicist David Bohm. Bohm is one example of a scientist influenced by Whitehead's philosophy.[153]

Theoretical physicist David Bohm. Bohm is one example of a scientist influenced by Whitehead's philosophy.[153]Scientists of the early 20th century for whom Whitehead's work has been influential include physical chemist Ilya Prigogine, biologist Conrad Hal Waddington, and geneticists Charles Birch and Sewall Wright.[18] Henry Murray dedicated his "Explorations in Personality" to Whitehead, a contemporary at Harvard.

In physics, Whitehead's theory of gravitation articulated a view that might perhaps be regarded as dual to Albert Einstein's general relativity. It has been severely criticized.[154][155] Yutaka Tanaka suggested that the gravitational constant disagrees with experimental findings, and proposed that Einstein's work does not actually refute Whitehead's formulation.[156] Whitehead's view has now been rendered obsolete, with the discovery of gravitational waves, phenomena observed locally that largely violate the kind of local flatness of space that Whitehead assumes. Consequently, Whitehead's cosmology must be regarded as a local approximation, and his assumption of a uniform spatio-temporal geometry, Minkowskian in particular, as an often-locally-adequate approximation. An exact replacement of Whitehead's cosmology would need to admit a Riemannian geometry. Also, although Whitehead himself gave only secondary consideration to quantum theory, his metaphysics of processes has proved attractive to some physicists in that field. Henry Stapp and David Bohm are among those whose work has been influenced by Whitehead.[153]

In the 21 st century, Whiteheadian thought is still a stimulating influence: Timothy E. Eastman and Hank Keeton's Physics and Whitehead (2004)[157] and Michael Epperson's Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (2004)[158] and Foundations of Relational Realism: A Topological Approach to Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Nature (2013),[159] aim to offer Whiteheadian approaches to physics. Brian G. Henning, Adam Scarfe, and Dorion Sagan's Beyond Mechanism (2013) and Rupert Sheldrake's Science Set Free (2012) are examples of Whiteheadian approaches to biology.

Ecology, economy, and sustainability Theologian, philosopher, and environmentalist John B. Cobb founded the Center for Process Studies in Claremont, California with David Ray Griffin in 1973, and is often regarded as the preeminent scholar in the field of process philosophy and process theology.[160][161][162][163]

Theologian, philosopher, and environmentalist John B. Cobb founded the Center for Process Studies in Claremont, California with David Ray Griffin in 1973, and is often regarded as the preeminent scholar in the field of process philosophy and process theology.[160][161][162][163]One of the most promising applications of Whitehead's thought in recent years has been in the area of ecological civilization, sustainability, and environmental ethics.

"Because Whitehead's holistic metaphysics of value lends itself so readily to an ecological point of view, many see his work as a promising alternative to the traditional mechanistic worldview, providing a detailed metaphysical picture of a world constituted by a web of interdependent relations."[24]

This work has been pioneered by John B. Cobb, whose book Is It Too Late? A Theology of Ecology (1971) was the first single-authored book in environmental ethics.[164] Cobb also co-authored a book with leading ecological economist and steady-state theorist Herman Daly entitled For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy toward Community, the Environment, and a Sustainable Future (1989), which applied Whitehead's thought to economics, and received the Grawemeyer Award for Ideas Improving World Order. Cobb followed this with a second book, Sustaining the Common Good: A Christian Perspective on the Global Economy (1994), which aimed to challenge "economists' zealous faith in the great god of growth."[165]

EducationWhitehead is widely known for his influence in education theory. His philosophy inspired the formation of the Association for Process Philosophy of Education (APPE), which published eleven volumes of a journal titled Process Papers on process philosophy and education from 1996 to 2008.[166] Whitehead's theories on education also led to the formation of new modes of learning and new models of teaching.

One such model is the ANISA model developed by Daniel C. Jordan, which sought to address a lack of understanding of the nature of people in current education systems. As Jordan and Raymond P. Shepard put it: "Because it has not defined the nature of man, education is in the untenable position of having to devote its energies to the development of curricula without any coherent ideas about the nature of the creature for whom they are intended."[167]

Another model is the FEELS model developed by Xie Bangxiu and deployed successfully in China. "FEELS" stands for five things in curriculum and education: Flexible-goals, Engaged-learner, Embodied-knowledge, Learning-through-interactions, and Supportive-teacher.[168] It is used for understanding and evaluating educational curriculum under the assumption that the purpose of education is to "help a person become whole." This work is in part the product of cooperation between Chinese government organizations and the Institute for the Postmodern Development of China.[71]

Whitehead's philosophy of education has also found institutional support in Canada, where the University of Saskatchewan created a Process Philosophy Research Unit and sponsored several conferences on process philosophy and education.[169] Howard Woodhouse at the University of Saskatchewan remains a strong proponent of Whiteheadian education.[170]

Three recent books which further develop Whitehead's philosophy of education include: Modes of Learning: Whitehead's Metaphysics and the Stages of Education (2012) by George Allan; and The Adventure of Education: Process Philosophers on Learning, Teaching, and Research (2009) by Adam Scarfe, and "Educating for an Ecological Civilization: Interdisciplinary, Experiential, and Relational Learning" (2017) edited by Marcus Ford and Stephen Rowe. "Beyond the Modern University: Toward a Constructive Postmodern University," (2002) is another text that explores the importance of Whitehead's metaphysics for thinking about higher education.

Business administrationWhitehead has had some influence on philosophy of business administration and organizational theory. This has led in part to a focus on identifying and investigating the effect of temporal events (as opposed to static things) within organizations through an “organization studies” discourse that accommodates a variety of 'weak' and 'strong' process perspectives from a number of philosophers.[171] One of the leading figures having an explicitly Whiteheadian and panexperientialist stance towards management is Mark Dibben,[172] who works in what he calls "applied process thought" to articulate a philosophy of management and business administration as part of a wider examination of the social sciences through the lens of process metaphysics. For Dibben, this allows "a comprehensive exploration of life as perpetually active experiencing, as opposed to occasional – and thoroughly passive – happening."[173] Dibben has published two books on applied process thought, Applied Process Thought I: Initial Explorations in Theory and Research (2008), and Applied Process Thought II: Following a Trail Ablaze (2009), as well as other papers in this vein in the fields of philosophy of management and business ethics.[174]

Margaret Stout and Carrie M. Staton have also written recently on the mutual influence of Whitehead and Mary Parker Follett, a pioneer in the fields of organizational theory and organizational behavior. Stout and Staton see both Whitehead and Follett as sharing an ontology that "understands becoming as a relational process; difference as being related, yet unique; and the purpose of becoming as harmonizing difference."[175] This connection is further analyzed by Stout and Jeannine M. Love in Integrative Process: Follettian Thinking from Ontology to Administration[176]

Political viewsWhitehead's political views sometimes appear to be libertarian without the label. He wrote:

Now the intercourse between individuals and between social groups takes one of two forms, force or persuasion. Commerce is the great example of intercourse by way of persuasion. War, slavery, and governmental compulsion exemplify the reign of force.[177]

On the other hand, many Whitehead scholars read his work as providing a philosophical foundation for the social liberalism of the New Liberal movement that was prominent throughout Whitehead's adult life. Morris wrote that "... there is good reason for claiming that Whitehead shared the social and political ideals of the new liberals."[178]

Primary worksBooks written by Whitehead, listed by date of publication.

• A Treatise on Universal Algebra. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1898. ISBN 1-4297-0032-7. Available online at

http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.chmm/1263316509.

• The Axioms of Descriptive Geometry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1907.[179] Available online at

http://quod.lib.umich.edu/u/umhistmath/ABN2643.0001.001.

• with Bertrand Russell. Principia Mathematica, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. Available online at

http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/b/bib/bibp ... 1.0001.001. Vol. 1 to *56 is available as a CUP paperback.[180][181][182]

• An Introduction to Mathematics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911. Available online at

http://quod.lib.umich.edu/u/umhistmath/AAW5995.0001.001. Vol. 56 of the Great Books of the Western World series.

• with Bertrand Russell. Principia Mathematica, Volume II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1912. Available online at

http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/b/bib/bibp ... 1.0002.001.

• with Bertrand Russell. Principia Mathematica, Volume III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913. Available online at

http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/b/bib/bibp ... 1.0003.001.

• The Organization of Thought Educational and Scientific. London: Williams & Norgate, 1917. Available online at

https://archive.org/details/organisationofth00whit.

• An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1919. Available online at

https://archive.org/details/enquiryconcernpr00whitrich.

• The Concept of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1920. Based on the November 1919 Tarner Lectures delivered at Trinity College. Available online at

https://archive.org/details/cu31924012068593.

• The Principle of Relativity with Applications to Physical Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922. Available online at

https://archive.org/details/theprincipleofre00whituoft.

• Science and the Modern World. New York: Macmillan Company, 1925. Vol. 55 of the Great Books of the Western World series.

• Religion in the Making. New York: Macmillan Company, 1926. Based on the 1926 Lowell Lectures.

• Symbolism, Its Meaning and Effect. New York: Macmillan Co., 1927. Based on the 1927 Barbour-Page Lectures delivered at the University of Virginia.

• Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York: Macmillan Company, 1929. Based on the 1927–28 Gifford Lectures delivered at the University of Edinburgh. The 1978 Free Press "corrected edition" edited by David Ray Griffin and Donald W. Sherburne corrects many errors in both the British and American editions, and also provides a comprehensive index.

• The Aims of Education and Other Essays. New York: Macmillan Company, 1929.

• The Function of Reason. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1929. Based on the March 1929 Louis Clark Vanuxem Foundation Lectures delivered at Princeton University.

• Adventures of Ideas. New York: Macmillan Company, 1933. Also published by Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1933.

• Nature and Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934.

• Modes of Thought. New York: MacMillan Company, 1938.

• "Mathematics and the Good." In The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, edited by Paul Arthur Schilpp, 666–681. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1941.

• "Immortality." In The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, edited by Paul Arthur Schilpp, 682–700. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1941.

• Essays in Science and Philosophy. London: Philosophical Library, 1947.

• with Allison Heartz Johnson, ed. The Wit and Wisdom of Whitehead. Boston: Beacon Press, 1948.

In addition, the Whitehead Research Project of the Center for Process Studies is currently working on a critical edition of Whitehead's writings, which is set to include notes taken by Whitehead's students during his Harvard classes, correspondence, and corrected editions of his books.[48]

• Paul A. Bogaard and Jason Bell, eds. The Harvard Lectures of Alfred North Whitehead, 1924–1925: Philosophical Presuppositions of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

See also• Great refusal

• Relationalism

References1. Alfred North Whitehead at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

2. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 39.

3. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), xii.

4. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), xiii.

5. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), xi.

6. Michel Weber and Will Desmond, eds., Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought, Volume 1 (Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag, 2008), 17.

7. John B. Cobb Jr. and David Ray Griffin, Process Theology: An Introductory Exposition (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976), 174.

8. Michel Weber and Will Desmond, eds., Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought, Volume 1 (Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag, 2008), 26.

9. An Interview with Donald Davidson.

10. Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, Dialogues II, Columbia University Press, 2007, p. vii.

11. John B. Cobb Jr. and David Ray Griffin, Process Theology: An Introductory Exposition (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976), 164-165.

12. John B. Cobb Jr. and David Ray Griffin, Process Theology: An Introductory Exposition (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1976), 175.

13. Thomas J. Fararo, "On the Foundations of the Theory of Action in Whitehead and Parsons", in Explorations in General Theory in Social Science, ed. Jan J. Loubser et al. (New York: The Free Press, 1976), chapter 5.

14. Michel Weber and Will Desmond, eds., Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought, Volume 1 (Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag, 2008), 25.

15. "Alfred North Whitehead - Biography". European Graduate School. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

16. Wolfgang Smith, Cosmos and Transcendence: Breaking Through the Barrier of Scientistic Belief (Peru, Illinois: Sherwood Sugden and Company, 1984), 3.

17. Michel Weber and Will Desmond, eds., Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought, Volume 1 (Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag, 2008), 13.

18. Charles Birch, "Why Aren't We Zombies? Neo-Darwinism and Process Thought", in Back to Darwin: A Richer Account of Evolution, ed. John B. Cobb Jr. (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2008), 252.

19. "Young Voegelin in America". 6 March 2011.

20. "Integrating Whitehead".

21. David Ray Griffin, Reenchantment Without Supernaturalism: A Process Philosophy of Religion (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), vii.

22. "The Modern Library's Top 100 Nonfiction Books of the Century", last modified April 30, 1999, The New York Times, accessed November 21, 2013,

https://www.nytimes.com/library/books/0 ... -list.html.

23. C. Robert Mesle, Process-Relational Philosophy: An Introduction to Alfred North Whitehead (West Conshohocken: Templeton Foundation Press, 2009), 9.

24. Philip Rose, On Whitehead (Belmont: Wadsworth, 2002), preface.

25. Cobb, John B., Jr.; Schwartz, Wm. Andrew (2018). Putting Philosophy to Work: Toward an Ecological Civilization. Process Century Press. ISBN 978-1940447339.

26. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 2.

27. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 13.

28. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 27.

29. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 44.

30. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 32–33.

31. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 54–60.

32. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 63.

33. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 72.

34. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 103.

35. On Whitehead the mathematician and logician, see Ivor Grattan-Guinness, The Search for Mathematical Roots 1870–1940: Logics, Set Theories, and the Foundations of Mathematics from Cantor through Russell to Gödel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), and Quine's chapter in Paul Schilpp, The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (New York: Tudor Publishing Company, 1941), 125–163.

36. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 112.

37. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 34.

38. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 2.

39. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 6-8.

40. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 26-27.

41. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 72-74.

42. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 127.

43. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 132.

44. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 3–4.

45. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 262.

46. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vols I & II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985 & 1990).

47. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 7.

48. "Critical Edition of Whitehead", last modified July 16, 2013, Whitehead Research Project, accessed November 21, 2013,

http://whiteheadresearch.org/research/c ... ease.shtml Archived 9 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

49. "The Edinburgh Critical Edition of the Complete Works of Alfred North Whitehead". Edinburgh University Press Books. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

50. Christoph Wassermann, "The Relevance of An Introduction to Mathematics to Whitehead's Philosophy", Process Studies17 (1988): 181. Available online at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

51. "Whitehead, Alfred North", last modified May 8, 2007, Gary L. Herstein, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed November 21, 2013,

http://www.iep.utm.edu/whitehed/.

52. George Grätzer, Universal Algebra (Princeton: Van Nostrand Co., Inc., 1968), v.

53. Cf. Michel Weber and Will Desmond (eds.). Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought (Frankfurt / Lancaster, Ontos Verlag, Process Thought X1 & X2, 2008) and Ronny Desmet & Michel Weber (edited by), Whitehead. The Algebra of Metaphysics. Applied Process Metaphysics Summer Institute Memorandum, Louvain-la-Neuve, Les Éditions Chromatika, 2010.

54. Alexander Macfarlane, "Review of A Treatise on Universal Algebra", Science 9 (1899): 325.

55. G. B. Mathews (1898) A Treatise on Universal Algebra from Nature 58:385 to 7 (#1504)

56. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 190–191.

57. Alfred North Whitehead, A Treatise on Universal Algebra (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1898), v. Available online at

http://projecteuclid.org/DPubS/Reposito ... type=pdf_158. Barron Brainerd, "Review of Universal Algebra by P. M. Cohn", American Mathematical Monthly, 74 (1967): 878–880.

59. Alfred North Whitehead, Principia Mathematica Volume 2, Second Edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1950), 83.

60. Hal Hellman, Great Feuds in Mathematics: Ten of the Liveliest Disputes Ever (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2006). Available online at

https://books.google.com/books?id=ft8bE ... &q&f=false61. "Principia Mathematica", last modified December 3, 2013, Andrew David Irvine, ed. Edward N. Zalta, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2013 Edition), accessed December 5, 2013,

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/princ ... tica/#HOPM.

62. Stephen Cole Kleene, Mathematical Logic (New York: Wiley, 1967), 250.

63. "'Principia Mathematica' Celebrates 100 Years", last modified December 22, 2010, NPR, accessed November 21, 2013,

https://www.npr.org/2010/12/22/13226587 ... -100-Years64. "Principia Mathematica", last modified December 3, 2013, Andrew David Irvine, ed. Edward N. Zalta, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2013 Edition), accessed December 5, 2013,

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/princ ... tica/#SOPM.

65. Alfred North Whitehead, An Introduction to Mathematics, (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1911), 8.

66. Christoph Wassermann, "The Relevance of An Introduction to Mathematics to Whitehead's Philosophy", Process Studies 17 (1988): 181–182. Available online at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

67. Christoph Wassermann, "The Relevance of An Introduction to Mathematics to Whitehead's Philosophy", Process Studies 17 (1988): 182. Available online at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November2013.

68. Committee To Inquire Into the Position of Classics in the Educational System of the United Kingdom, Report of the Committee Appointed by the Prime Minister to Inquire into the Position of Classics in the Educational System of the United Kingdom, (London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1921), 1, 282. Available online at

https://archive.org/details/reportofcommitt00grea.

69. Alfred North Whitehead, The Aims of Education and Other Essays (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 1–2.

70. Alfred North Whitehead, The Aims of Education and Other Essays (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 2.

71. "China embraces Alfred North Whitehead", last modified December 10, 2008, Douglas Todd, The Vancouver Sun, accessed December 5, 2013,

http://blogs.vancouversun.com/2008/12/1 ... whitehead/.

72. Alfred North Whitehead, The Aims of Education and Other Essays (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 13.

73. Alfred North Whitehead, The Aims of Education and Other Essays (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 93.

74. Alfred North Whitehead, The Aims of Education and Other Essays (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 98.

75. "An Iconic College View: Harvard University, circa 1900. Richard Rummell (1848–1924)", last modified July 6, 2011, Graham Arader, accessed December 5, 2013,

http://grahamarader.blogspot.com/2011/0 ... rsity.html.

76. Alfred North Whitehead to Bertrand Russell, February 13, 1895, Bertrand Russell Archives, Archives and Research Collections, McMaster Library, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

77. A. J. Ayer, Language, Truth and Logic, (New York: Penguin, 1971), 22.

78. George P. Conger, "Whitehead lecture notes: Seminary in Logic: Logical and Metaphysical Problems", 1927, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

79. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 4.

80. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 11.

81. Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 17.

82. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 18.

83. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 127, 133.

84. Gary Dorrien, The Making of American Liberal Theology: Crisis, Irony, and Postmodernity, 1950–2005 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006), 123–124.

85. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol II (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1990), 250.

86. Gary Dorrien, "The Lure and Necessity of Process Theology", CrossCurrents 58 (2008): 320.

87. Henry Nelson Wieman, "A Philosophy of Religion", The Journal of Religion 10 (1930): 137.

88. Peter Simons, "Metaphysical systematics: A lesson from Whitehead", Erkenntnis 48 (1998), 378.

89. Isabelle Stengers, Thinking with Whitehead: A Free and Wild Creation of Concepts, trans. Michael Chase (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2011), 6.

90. David Ray Griffin, Whitehead's Radically Different Postmodern Philosophy: An Argument for Its Contemporary Relevance(Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), viii–ix.

91. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 208.

92. Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 52–55.

93. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 34–35.

94. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 34.

95. Alfred North Whitehead, Science and the Modern World (New York: The Free Press, 1967), 54–55.

96. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 183.

97. Alfred North Whitehead, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 38–39.

98. Louise R. Heath, "Notes on Whitehead's Philosophy 3b: Philosophical Presuppositions of Science", September 27, 1924, Whitehead Research Project, Center for Process Studies, Claremont, California.

99. Alfred North Whitehead, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 26.

100. Alfred North Whitehead, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 39.

101. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 19.

102. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 21.

103. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 23.

104. Charles Hartshorne, "Freedom Requires Indeterminism and Universal Causality", The Journal of Philosophy 55 (1958): 794.

105. John B. Cobb, A Christian Natural Theology (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1978), 52.

106. David Ray Griffin, Reenchantment Without Supernaturalism: A Process Philosophy of Religion (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 79.

107. Alfred North Whitehead, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 44.

108. Alfred North Whitehead, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 24.

109. Alfred North Whitehead, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 3.

110. Alfred North Whitehead, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 4.

111. Alfred North Whitehead, Symbolism: Its Meaning and Effect (New York: Fordham University Press, 1985), 49.

112. Alfred North Whitehead, The Function of Reason (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958), 4.

113. Alfred North Whitehead, The Function of Reason (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958), 4–5.

114. Alfred North Whitehead, The Function of Reason (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958), 8.

115. David Ray Griffin, Reenchantment Without Supernaturalism: A Process Philosophy of Religion (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 97.

116. Roland Faber, God as Poet of the World: Exploring Process Theologies (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), chapters 4–5.

117. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 342.

118. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 343.

119. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 207.

120. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 345.

121. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 344.

122. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 346.

123. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 347–348, 351.

124. Bruce G. Epperly, Process Theology: A Guide for the Perplexed (New York: T&T Clark, 2011), 12.

125. Roland Faber, God as Poet of the World: Exploring Process Theologies (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), chapter 1.

126. Alfred North Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York: Fordham University Press, 1996), 15–16.

127. Alfred North Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York: Fordham University Press, 1996), 16–17.

128. Alfred North Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York: Fordham University Press, 1996), 15.

129. Alfred North Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York: Fordham University Press, 1996), 18.

130. Alfred North Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York: Fordham University Press, 1996), 59.

131. Alfred North Whitehead, Religion in the Making (New York: Fordham University Press, 1996), 60.

132. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 16.

133. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 15.

134. George Garin, "Theistic Evolution in a Sacramental Universe: The Theology of William Temple Against the Background of Process Thinkers (Whitehead, Alexander, Etc.)," (Protestant University Press, Kinshasa, The Congo, 1991).

135. Gary Dorrien, "The Lure and Necessity of Process Theology", CrossCurrents 58 (2008): 321–322.

136. David Ray Griffin, "John B. Cobb, Jr.: A Theological Biography", in Theology and the University: Essays in Honor of John B. Cobb, Jr., ed. David Ray Griffin and Joseph C. Hough, Jr. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991), 229.

137. Gary Dorrien, "The Lure and Necessity of Process Theology", CrossCurrents 58 (2008): 334.

138. Victor Lowe, Alfred North Whitehead: The Man and his Work, Vol I (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1985), 5.

139. "About Us".

http://www.postmodernchina.org. The Institute for the Postmodern Development of China. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

140. "Whitehead, Alfred North", last modified May 8, 2007, Gary L. Herstein, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed July 20, 2015,

http://www.iep.utm.edu/whitehed/.

141. "Quine Biography", last modified October 2003, John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, accessed December 5, 2013,

http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk ... Quine.html.

142. John Searle, "Contemporary Philosophy in the United States", in N. Bunnin and E.P. Tsui-James, eds., The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy, 2nd ed., (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003), 1.

143. Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, trans. Tom Conley (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 76.

144. Bruno Latour, preface to Thinking with Whitehead: A Free and Wild Creation of Concepts, by Isabelle Stengers, trans. Michael Chase (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2011), x.

145. "Alfred North Whitehead", last modified March 10, 2015, Andrew David Irvine, ed. Edward N. Zalta, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition), accessed July 20, 2015,

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/whitehead/#WI146. "Alfred North Whitehead", last modified October 1, 2013, Andrew David Irvine, ed. Edward N. Zalta, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2013 Edition), accessed November 21, 2013,

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/whitehead/#WI147. Charles Hartshorne, A Christian Natural Theology, 2nd edition (Louisville, Westminster John Knox Press, 2007), 112.

148. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 351.

149. Charles Hartshorne, The Divine Relativity: A Social Conception of God (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964), 42–43.

150. See part IV of Mesle's Process Theology: A Basic Introduction (St. Louis: Chalice Press, 1993).

151. "Search Results For: SUNY series in Constructive Postmodern Thought", Sunypress.edu, accessed December 5, 2013,

http://www.sunypress.edu/Searchadv.aspx ... oryID=6899.

152. "Richard Rorty", last modified June 16, 2007, Bjørn Ramberg, ed. Edward N. Zalta, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(Spring 2009 Edition), accessed December 5, 2013,

http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2 ... ies/rorty/.

153. See David Ray Griffin, Physics and the Ultimate Significance of Time (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986).

154. Chandrasekhar, S. (1979). Einstein and general relativity, Am. J. Phys. 47: 212–217.

155. Will, C.M. (1981/1993). Theory and Experiment in Gravitational Physics, revised edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, ISBN 978-0-521-43973-2, p. 139.

156. Yutaka Tanaka, "The Comparison between Whitehead's and Einstein's Theories of Relativity", Historia Scientiarum 32 (1987).

157. Timothy E. Eastman and Hank Keeton, eds., Physics and Whitehead: Quantum, Process, and Experience (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004).

158. Michael Epperson, Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (New York: Fordham University Press, 2004).

159. Michael Epperson & Elias Zafiris, Foundations of Relational Realism: A Topological Approach to Quantum Mechanics and the Philosophy of Nature (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013).

160. Roland Faber, God as Poet of the World: Exploring Process Theologies (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), 35.

161. C. Robert Mesle, Process Theology (St. Louis: Chalice Press, 1993), 126.

162. Gary Dorrien, "The Lure and Necessity of Process Theology", CrossCurrents 58 (2008): 316.

163. Monica Coleman, Nancy R. Howell, and Helene Tallon Russell, Creating Women's Theology: A Movement Engaging Process Thought (Wipf and Stock, 2011), 13.

164. "History of Environmental Ethics for the Novice", last modified March 15, 2011, The Center for Environmental Philosophy, accessed November 21, 2013,

http://www.cep.unt.edu/novice.html.

165. John B. Cobb Jr., Sustaining the Common Good: A Christian Perspective on the Global Economy (Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press, 1994), back cover.

166. See Process Papers, a publication of the Association for Process Philosophy of Education. Volume 1 published in 1996, Volume 11 (final volume) published in 2008.

167. Daniel C. Jordan and Raymond P. Shepard, "The Philosophy of the ANISA Model", Process Papers 6, 38–39.

168. "FEELS: A Constructive Postmodern Approach To Curriculum and Education", Xie Bangxiu, JesusJazzBuddhism.org, accessed December 5, 2013,

http://www.jesusjazzbuddhism.org/feels.html Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

169. "International Conferences – University of Saskatchewan", University of Saskatchewan, accessed December 5, 2013,

https://www.usask.ca/usppru/internation ... rences.php.

170. "Dr. Howard Woodhouse" Archived 7 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, University of Saskatchewan, accessed December 5, 2013

171. Tor Hernes, A Process Theory of Organization (Oxford University Press, 2014)

172. Mark R. Dibben and John B. Cobb Jr., "Special Focus: Process Thought and Organization Studies," in Process Studies 32(2003).

173. "Mark Dibben – School of Management – University of Tasmania, Australia", last modified July 16, 2013, University of Tasmania, accessed November 21, 2013,

http://www.utas.edu.au/business-and-eco ... ark-Dibben Archived 13 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

174. Mark Dibben, "Exploring the Processual Nature of Trust and Cooperation in Organisations: A Whiteheadian Analysis," in Philosophy of Management 4 (2004): 25-39; Mark Dibben, "Organisations and Organising: Understanding and Applying Whitehead’s Processual Account," in Philosophy of Management 7 (2009); Cristina Neesham and Mark Dibben, "The Social Value of Business: Lessons from Political Economy and Process Philosophy," in Applied Ethics: Remembering Patrick Primeaux(Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations, Volume 8), ed. Michael Schwartz and Howard Harris (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2012): 63-83.

175. Margaret Stout & Carrie M. Staton, "The Ontology of Process Philosophy in Follett's Administrative Theory" Administrative Theory & Praxis 33 (2011): 268.

176. Margaret Stout & Jeannine M. Love, Integrative Process: Follettian Thinking from Ontology to Administration, (Anoka, MN: Process Century Press 2015).

177. Adventures of Ideas p. 105, 1933 edition; p. 83, 1967 ed.

178. Morris, Randall C., Journal of the History of Ideas 51: 75-92. p. 92.

179. F.W. Owens, "Review: The Axioms of Descriptive Geometry by A. N. Whitehead", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 15 (1909): 465–466. Available online at

http://www.ams.org/journals/bull/1909-1 ... 1815-4.pdf.

180. James Byrnie Shaw, "Review: Principia Mathematica by A. N. Whitehead and B. Russell, Vol. I, 1910", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 18 (1912): 386–411. Available online at

http://www.ams.org/journals/bull/1912-1 ... 2233-4.pdf.

181. Benjamin Abram Bernstein, "Review: Principia Mathematica by A. N. Whitehead and B. Russell, Vol. I, Second Edition, 1925", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 32 (1926): 711–713. Available online at

http://www.ams.org/journals/bull/1926-3 ... 4306-8.pdf.

182. Alonzo Church, "Review: Principia Mathematica by A. N. Whitehead and B. Russell, Volumes II and III, Second Edition, 1927", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 34 (1928): 237–240. Available online at

http://www.ams.org/journals/bull/1928-3 ... 4525-1.pdf.

Further readingFor the most comprehensive list of resources related to Whitehead, see the thematic bibliography of the Center for Process Studies.

• Casati, Roberto, and Achille C. Varzi. Parts and Places: The Structures of Spatial Representation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1999.

• Ford, Lewis. Emergence of Whitehead's Metaphysics, 1925–1929. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985.

• Hartshorne, Charles. Whitehead's Philosophy: Selected Essays, 1935–1970. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1972.

• Henning, Brian G. The Ethics of Creativity: Beauty, Morality, and Nature in a Processive Cosmos. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005.

• Holtz, Harald and Ernest Wolf-Gazo, eds. Whitehead und der Prozeßbegriff / Whitehead and The Idea of Process. Proceedings of the First International Whitehead-Symposion. Verlag Karl Alber, Freiburg i. B. / München, 1984. ISBN 3-495-47517-6

• Jones, Judith A. Intensity: An Essay in Whiteheadian Ontology. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1998.

• Kraus, Elizabeth M. The Metaphysics of Experience. New York: Fordham University Press, 1979.

• Malik, Charles H.. The Systems of Whitehead's Metaphysics. Zouq Mosbeh, Lebanon: Notre Dame Louaize, 2016. 436 pp.

• McDaniel, Jay. What is Process Thought?: Seven Answers to Seven Questions. Claremont: P&F Press, 2008.

• McHenry, Leemon. The Event Universe: The Revisionary Metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015.

• Nobo, Jorge L. Whitehead's Metaphysics of Extension and Solidarity. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986.

• Price, Lucien. Dialogues of Alfred North Whitehead. New York: Mentor Books, 1956.

• Quine, Willard Van Orman. "Whitehead and the rise of modern logic." In The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead, edited by Paul Arthur Schilpp, 125–163. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1941.

• Rapp, Friedrich and Reiner Wiehl, eds. Whiteheads Metaphysik der Kreativität. Internationales Whitehead-Symposium Bad Homburg 1983. Verlag Karl Alber, Freiburg i. B. / München, 1986. ISBN 3-495-47612-1

• Rescher, Nicholas. Process Metaphysics. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995.

• Rescher, Nicholas. Process Philosophy: A Survey of Basic Issues. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001.

• Schilpp, Paul Arthur, ed. The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1941. Part of the Library of Living Philosophers series.

• Siebers, Johan. The Method of Speculative Philosophy: An Essay on the Foundations of Whitehead's Metaphysics. Kassel: Kassel University Press GmbH, 2002. ISBN 3-933146-79-8

• Smith, Olav Bryant. Myths of the Self: Narrative Identity and Postmodern Metaphysics. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2004. ISBN 0-7391-0843-3

– Contains a section called "Alfred North Whitehead: Toward a More Fundamental Ontology" that is an overview of Whitehead's metaphysics.

• Weber, Michel. Whitehead's Pancreativism — The Basics. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag, 2006.

• Weber, Michel. Whitehead’s Pancreativism — Jamesian Applications, Frankfurt / Paris: Ontos Verlag, 2011.

• Weber, Michel and Will Desmond (eds.). Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought, Frankfurt / Lancaster: Ontos Verlag, 2008.

• Alan Van Wyk and Michel Weber (eds.). Creativity and Its Discontents. The Response to Whitehead's Process and Reality, Frankfurt / Lancaster: Ontos Verlag, 2009.

• Will, Clifford. Theory and Experiment in Gravitational Physics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

External links• The Philosophy of Organism in Philosophy Now magazine. An accessible summary of Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy.

• Center for Process Studies in Claremont, California. A faculty research center of Claremont School of Theology, in association with Claremont Graduate University. The Center organizes conferences and events and publishes materials pertaining to Whitehead and process thought. It also maintains extensive Whitehead-related bibliographies.

• Summary of Whitehead's Philosophy A Brief Introduction to Whitehead's Metaphysics

• Society for the Study of Process Philosophies, a scholarly society that holds periodic meetings in conjunction with each of the divisional meetings of the American Philosophical Association, as well as at the annual meeting of the Society for the Advancement of American Philosophy.

• "Alfred North Whitehead" in the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, by John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson.

• "Alfred North Whitehead: New World Philosopher" at the Harvard Square Library.

• Jesus, Jazz, and Buddhism: Process Thinking for a More Hospitable World

• "What is Process Thought?" an introductory video series to process thought by Jay McDaniel.

• Centre de philosophie pratique « Chromatiques whiteheadiennes »

• "Whitehead's Principle of Relativity" by John Lighton Synge on arXiv.org

• Whitehead at Monoskop.org, with extensive bibliography.

• Works by Alfred North Whitehead at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Alfred North Whitehead at Internet Archive

• Works by Alfred North Whitehead at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)