Ramayana

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/17/21

According to R.P. Tripathi, professor of ancient history at Allahabad University, "History requires concrete evidence in the form of coins, inscriptions, etc. to prove the existence of a character. Even if we take into account places mentioned in the Ramayana like Chitrakoot, Ayodhya, which still exist, the fact is that Ramayana is not a historical text."...

"In Ramayana's case, there is no evidence to prove that it is anything else except a myth. There is also no evidence -- either historical or archaeological -- which proves that Ram ever existed or that he ruled Ayodhya" claims S. Settar [former chairman of the Indian Council of Historical Research.

-- For Historians, Ram Remains a Myth, by Atul Sethi, Times of India, 9/14/07

Dasharatha was the king of Kosala kingdom and the descendent of Ikshavaku Dynasty and father of the Lord Rama. His capital was Ayodhya. Dasharatha was the son of Aja and Indumati. He had three main throne queens: Kausalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra, and from these unions were born Rama, Bharata, Lakshmana and Shatrughna. He is mentioned [in the] Ramayana and Vishnu Purana.

King Dasharatha was an incarnation of Svayambhuva Manu, the son of the Hindu creator god, Brahma.

Dasharatha was the son of King Aja of Kosala and Indumati of Vidarbha. His birth name was Nemi, but he acquired the name Dasharatha as his chariot could move in all ten directions, fly, as well as come down to earth, and he could fight with ease in all of these directions.

-- Dasharatha, by Wikipedia

Ramayana

रामायणम्

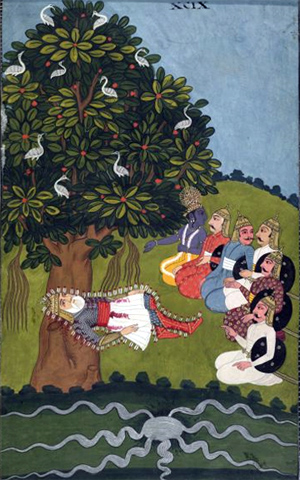

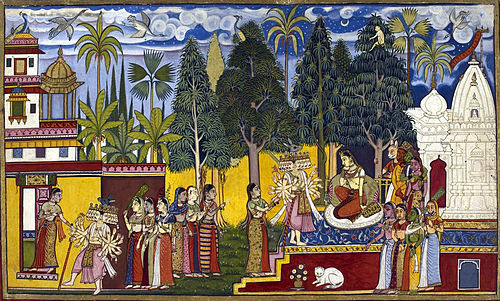

Rama with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana during exile in forest, manuscript, ca. 1780

Information

Religion Hinduism

Author Valmiki

Language Sanskrit

Verses 24,000

Rāmāyana (/rɑːˈmɑːjənə/;[1][2] Sanskrit: रामायणम्,[3] IAST: Rāmāyaṇam pronounced [ɽaːˈmaːjɐɳɐm]) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India, the other being the Mahābhārata. Along with the Mahābhārata, it forms the Hindu Itihasa.[4]

The epic, traditionally ascribed to the Maharishi Valmiki, narrates the life of Rama, a legendary prince of Ayodhya city in the kingdom of Kosala. The epic follows his fourteen-year exile to the forest urged by his father King Dasharatha, on the request of Rama's stepmother Kaikeyi; his travels across forests in the Indian subcontinent with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana, the kidnapping of Sita by Ravana – the king of Lanka, that resulted in war; and Rama's eventual return to Ayodhya to be crowned king amidst jubilation and celebration.

The Ramayana is one of the largest ancient epics in world literature. It consists of nearly 24,000 verses (mostly set in the Shloka/Anustubh meter), divided into seven kāṇḍas, the first and the seventh being later additions.[5] It belongs to the genre of Itihasa, narratives of past events (purāvṛtta), interspersed with teachings on the goals of human life. Scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text range from the 7th to 4th centuries BCE,[6][7][unreliable source?] with later stages extending up to the 3rd century CE.[8]

More recent suggestions about dating include Grintser's suggestion that the period of formation for both epics is approximately from the 4th century B.C. to the 3rd century A.D., Ananda Guruge's placing of the Ramayana somewhere before 300 B.C., P.L. Bhargava's dating of 600 B.C., Goldman's suggestion of a date for the oldest parts no later than the middle of the 6th century B.C. but not before the beginning of the 7th century (then defined as 'sometime between 750 and 500 B.C.'), and Gregory Alles's arguments for a Sunga dating for the core (by which, however, he means basically the whole of the Ayodhya to Yuddha kandas) and a location for its author in the Northeast.69 [See Grintser 1974: 136-152, Guruge 199: 38; Bhargava 1965, Ramayana 1984: I, 22-23, Alles 1988-89] My own statement was that the first stage belongs to the period from about the 5th to the 4th century B.C. and this remains my view, even after taking into account the recent strong arguments for a later dating for the Buddha; in relative terms, therefore, this dating represents a limited upward revision.

The Balakanda has generally been recognised as being, equally with the Uttarakanda, a later addition to the original epic, although there have been attempts to argue that it is essential to the narrative or that some part of it is as old as the rest.70 [An example of the sfirst trend is that Ramashraya Sharma (1971: 6-7) finds references to the Balakanda at 2.110.36-50 (Sita's account of Rama bending Siva's bow) and 3.36.3-16 (Marica's account of his previous encounter with Rama), and to the Uttarakanda at 5.2.19-20 (Lanka built by Visvakarman and formerly occupied by Kubera), 8.14 (Ravana scarred by Visnu's cakra), 44.7-8 (Ravana's conquest of the gods), 49.24-26 (Rama is human and Sugriva a monkey -- implying Ravana's boon) and 1031* 2-3 (the shaking of Kailasa). Similarly, Goldman (Ramayana 1984:I, 64) asserts that 'the "genuine" books contain at least two references to the events of Book One', citing the same two passages and noting their close similarities with the relevant Balakanda passages; however, by declaring that these passages are summarising the Balakanda material he prejudges the issue of the direction of borrowing. More probably, the Bala and Uttara kanda passages are expanding on the hints in the other books.] Less attention has been drawn to the fact that parts of its narrative are totally unsupported elsewhere. For example, there is no evidence outside 1.15-17 that Rama and his brothers were born more or less simultaneouslky or that Laksmana and Satrughna are twins, which contrasts with Kusa and Lava being emphatically called yamajata in the Uttarakanda and Laksmana and Satrughna themselves being explicitly called twins by Kalidasa (Raghuvamsa 10.71). Nor is there any reference elsewhere in ...

-- The Sanskrit Epics, by John Brockington

There are many versions of Ramayana in Indian languages, besides Buddhist, Sikh, and Jain adaptations. There are also Cambodian (Reamker), Indonesian, Filipino, Thai (Ramakien), Lao, Burmese and Malay versions of the tale. Retellings include Kamban's Ramavataram in Tamil (c. 11th–12th century),...

Kambar is generally dated after the vaishnavite philosopher, Ramanuja, as the poet refers to the latter in his work, the Sadagopar Andhadhi.

-- Kambar (poet), by Wikipedia

A number of traditional biographies of Ramanuja are known, some written in 12th century, but some written centuries later such as the 17th or 18th century, particularly after the split of the Śrīvaiṣṇava community into the Vadakalais and Teṉkalais, where each community created its own version of Ramanuja's hagiography. The Muvāyirappaṭi Guruparamparāprabhāva by Brahmatantra Svatantra Jīyar represents the earliest Vadakalai biography, and reflects the Vadakalai view of the succession following Ramanuja. Ārāyirappaṭi Guruparamparāprabhāva, on the other hand, represents the Tenkalai biography. Other late biographies include the Yatirajavaibhavam by Andhrapurna.

Modern scholarship has questioned the reliability of these hagiographies. Scholars question their reliability because of claims which are impossible to verify, or whose historical basis is difficult to trace with claims such as Ramanuja learned the Vedas when he was an eight-day-old baby, he communicated with God as an adult, that he won philosophical debates with Buddhists, Advaitins and others because of supernatural means such as turning himself into "his divine self Sesha" to defeat the Buddhists, or God appearing in his dream when he prayed for arguments to answer Advaita scholars. According to J. A. B. van Buitenen, the hagiographies are "legendary biographies about him, in which a pious imagination has embroidered historical details".

-- Ramanuja, by Wikipedia

Gona Budda Reddy's Ranganatha Ramayanam in Telugu (c. 13th century), Madhava Kandali's Saptakanda Ramayana in Assamese (c. 14th century), Krittibas Ojha's Krittivasi Ramayan (also known as Shri Ram Panchali) in Bengali (c. 15th century), Sarala Das' Vilanka Ramayana (c. 15th century)[9][10][11][12] and Balarama Dasa's Jagamohana Ramayana (also known as the Dandi Ramayana) (c. 16th century) both in Odia, sant Eknath's Bhavarth Ramayan (c. 16th century) in Marathi, Tulsidas' Ramcharitamanas (c. 16th century) in Awadhi (which is an eastern form of Hindi) and Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan's Adhyathmaramayanam in Malayalam(c. 17th century).

The Ramayana was an important influence on later Sanskrit poetry and Hindu life and culture. The characters Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Bharata, Hanuman, and Ravana are all fundamental to the cultural consciousness of the South Asian nations of India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and the South-East Asian countries of Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. Its most important moral influence was the importance of virtue, in the life of a citizen and in the ideals of the formation of a state or of a functioning society.

Etymology

The name Rāmāyaṇa is composed of two words, Rāma and ayaṇa. Rāma, the name of the central figure of the epic, has two contextual meanings. In the Atharvaveda, it means "dark, dark-coloured, black" and is related to the word rātri which means "darkness or stillness of night". The other meaning, which can be found in the Mahabharata, is "pleasing, pleasant, charming, lovely, beautiful".[13][14] The word ayana means travel or journey. Thus, Ramayana means Rama's progress. But there is a minor catch. While ayana means travel or journey, ayaṇa is a meaningless word. This transformation of ayana into ayaṇa occurs because of a Sanskrit grammar rule known as internal sandhi.[15][16]

Textual characteristics

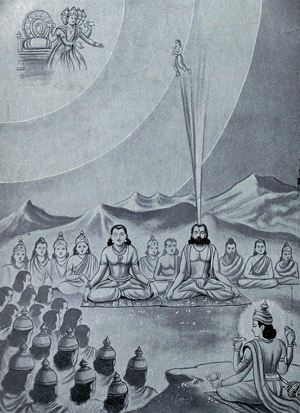

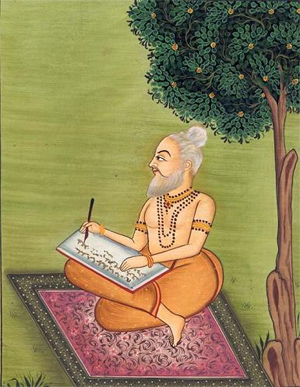

An artist's impression of sage Valmiki composing the Ramayana

Genre

The Ramayana belongs to the genre of Itihasa, narratives of past events (purāvṛtta), which includes the Mahabharata, the Puranas and the Ramayana. The genre also includes teachings on the goals of human life. It depicts the duties of relationships, portraying ideal characters like the ideal father, the ideal servant, the ideal brother, the ideal husband and the ideal king. Like the Mahabharata, Ramayana presents the teachings of ancient Hindu sages in narrative allegory, interspersing philosophical and ethical elements.

Structure

In its extant form, Valmiki's Ramayana is an epic poem of some 24,000 verses, divided into seven kāṇḍas (Bālakāṇḍa, Ayodhyakāṇḍa, Araṇyakāṇḍa, Kiṣkindakāṇḍa, Sundarākāṇḍa, Yuddhakāṇḍa, Uttarakāṇḍa), and about 500 sargas (chapters).[5][17]

Dating

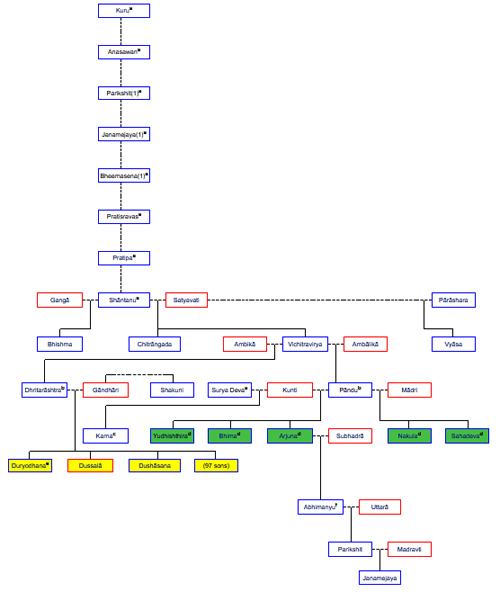

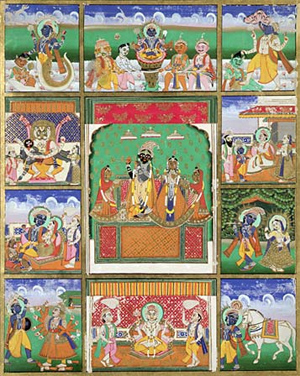

Rama (left third from top) depicted in the Dashavatara, the ten avatars of Vishnu. Painting from Jaipur, now at the Victoria and Albert Museum

According to Hindu tradition, the narrative of the Ramayana takes place during a period of time known as Treta Yuga (2,163,102 BCE - 867,102 BCE).[18]

According to Robert P. Goldman, the oldest parts of the Ramayana date to between the mid-7th century BCE and the mid-6th century BCE. This is due to the narrative not mentioning Buddhism nor the prominence of Magadha. The text also mentions Ayodhya as the capital of Kosala, rather than its later name of Saketa or the successor capital of Shravasti.[6] In terms of narrative time, the action of the Ramayana predates the Mahabharata. However, it is felt that the general cultural background of the Ramayana is one of the post-urbanization periods of the eastern part of north India, while the Mahabharata reflects the Kuru areas west of this, from the Rigvedic to the late Vedic period. Scholarly estimates for the earliest stage of the text range from the 7th to 4th centuries BCE,[6][7][unreliable source?] with later stages extending up to the 3rd century CE.[8]

The names of the characters (Rama, Sita, Dasharatha, Janaka, Vashista, Vishwamitra) are all known only in the late Vedic literature. For instance, a king named Janaka appears in a lengthy dialogue in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad with no reference to Rama or the Ramayana.[19] However, nowhere in the surviving Vedic poetry is there a story similar to the Ramayana of Valmiki. According to the modern academic view, Vishnu, who, according to Bala Kanda, was incarnated as Rama, first came into prominence with the epics themselves and further, during the Puranic period of the later 1st millennium CE. Also, in the epic Mahabharata, there is a version of the Ramayana known as Ramopakhyana. This version is depicted as a narration to Yudhishthira.

Books two to six are the oldest portion of the epic, while the first and last books (Bala Kand and Uttara Kand, respectively) seem to be later additions. Style differences and narrative contradictions between these two volumes and the rest of the epic have led scholars since Hermann Jacobi to the present toward this consensus.[20]

Recensions

The Ramayana text has several regional renderings, recensions and sub recensions. Textual scholar Robert P. Goldman differentiates two major regional revisions: the northern (n) and the southern (s). Scholar Romesh Chunder Dutt writes that "the Ramayana, like the Mahabharata, is a growth of centuries, but the main story is more distinctly the creation of one mind."

A Times of India report dated 18 December 2015 informs about the discovery of a 6th-century manuscript of the Ramayana at the Asiatic Society library, Kolkata.[21]

There has been discussion as to whether the first and the last volumes (Bala Kand and Uttara Kand) of Valmiki's Ramayana were composed by the original author. The uttarākāṇḍa, the bālakāṇḍa, although frequently counted among the main ones, is not a part of the original epic. Though Balakanda is sometimes considered in the main epic, according to many Uttarakanda is certainly a later interpolation and thus is not attributed to the work of Maharshi Valmiki.[5] This fact is reaffirmed by the absence of these two Kāndas in the oldest manuscript.[21] Many Hindus don't believe they are integral parts of the scripture because of some style differences and narrative contradictions between these two volumes and the rest.[citation needed]

Characters

Rama seated with Sita, fanned by Lakshmana, while Hanuman pays his respects

Statue of Ravana at Koneswaram Hindu Temple, Sri Lanka.

Main article: List of characters in Ramayana

Ikshvaku Dynasty

• Dasharatha is king of Ayodhya and father of Rama. He has three queens, Kausalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra, and four sons: Bharata, twins Lakshmana and Shatrughna, and Rama. Once, Kaikeyi saved Dasharatha in a war and as a reward, she got the privilege from Dasaratha to fulfill two of her wishes at any time in her lifetime. She made use of the opportunity and forced Dasharatha to make their son Bharata crown prince and send Rama into exile for 14 years. Dasharatha dies heartbroken after Rama goes into exile.

• Rama is the main character of the tale. Portrayed as the seventh avatar of god Vishnu, he is the eldest and favorite son of Dasharatha, the king of Ayodhya and his Chief Queen, Kausalya. He is portrayed as the epitome of virtue. Dasharatha is forced by Kaikeyi to command Rama to relinquish his right to the throne for fourteen years and go into exile. Rama kills the evil demon Ravana, who abducted his wife Sita, and later returns to Ayodhya to form an ideal state.

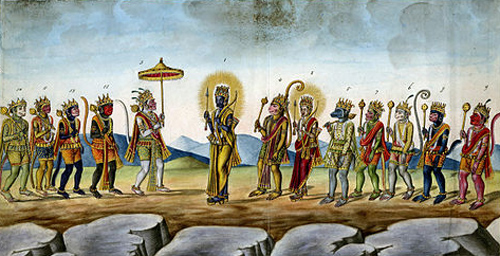

Rama and the Vanara chiefs

• Sita (Vaidehi) is another of the tale's protagonists. She was the blood of sages who sacrificed their lives to develop the powerful force to get rid of earth from demons. This blood was collected in a pot and was buried in Earth, so she is called the daughter of Mother Earth, adopted by King Janaka and Rama's beloved wife. Rama went to Mithila and got a chance to marry her by breaking the Shiv Dhanush (bow) while trying to tie a knot to it in a competition organized by King Janaka of Mithila. The competition was to find the most suitable husband for Sita and many princes from different states competed to win her. Sita is the avatar of goddess Lakshmi, the consort of Vishnu. Sita is portrayed as the epitome of female purity and virtue. She follows her husband into exile and is abducted by the Lanka's king Ravana. She is imprisoned on the island of Lanka, until Rama rescues her by defeating Ravana. Later, she gives birth to twin boys Lava and Kusha.

• Bharata is the son of Dasharatha and Queen Kaikeyi. when he learns that his mother Kaikeyi has forced Rama into exile and caused Dasharatha to die brokenhearted, he storms out of the palace and goes in search of Rama in the forest. When Rama refuses to return from his exile to assume the throne, Bharata obtains Rama's sandals and places them on the throne as a gesture that Rama is the true king. Bharata then rules Ayodhya as the regent of Rama for the next fourteen years, staying outside the city of Ayodhya. He was married to Mandavi.

• Lakshmana (Saumitra) is a younger brother of Rama, who chose to go into exile with him. He is the son of King Dasharatha and Queen Sumitra and twin of Shatrughna. Lakshmana is portrayed as an avatar of Shesha, the nāga associated with the god Vishnu. He spends his time protecting Sita and Rama, during which time he fights the demoness Shurpanakha. He is forced to leave Sita, who was deceived by the demon Maricha into believing that Rama was in trouble. Sita is abducted by Ravana upon his leaving her. He was married to Sita's younger sister Urmila.

• Shatrughna (Shatrughna means Ripudaman: Killer of enemies) is a son of Dasharatha and his third wife Queen Sumitra. He is the youngest brother of Rama and also the twin brother of Lakshmana. He was married to Shrutakirti.

Allies of Rama

The vanaras constructing the Rama Setu Bridge to Lanka, makaras and fish also aid the construction. A 9th century Prambanan bas-relief, Central Java, Indonesia.

Vanara

• Hanuman is a vanara belonging to the kingdom of Kishkindha. He is an ideal bhakta of Rama. He is born as son of Kesari, a Vanara king in Sumeru region and his wife Añjanā. He plays an important part in locating Sita and in the ensuing battle. Hanuman is incarnation of Lord Shiva.

• Sugriva, a vanara king who helped Rama regain Sita from Ravana. He had an agreement with Rama through which Vali – Sugriva's brother and king of Kishkindha – would be killed by Rama in exchange for Sugriva's help in finding Sita. Sugriva ultimately ascends the throne of Kishkindha after the slaying of Vali and fulfills his promise by putting the Vanara forces at Rama's disposal. He was son of God Surya and was married to Rumā.

• Angada is a vanara and the son of Vali (vanar king of Kishkindha before Sugriva) who helped Rama find his wife Sita and fight her abductor, Ravana, in Ramayana. He was son of Vali and Tara and nephew of Sugriva. Angada and Tara are instrumental in reconciling Rama and his brother, Lakshmana, with Sugriva after Sugriva fails to fulfill his promise to help Rama find and rescue his wife. Together they are able to convince Sugriva to honour his pledge to Rama instead of spending his time carousing and drinking.

Riksha

• Jambavan/Jamvanta is known as Riksharaj (King of the Rikshas). He is son of Lord Brahma. Rikshas are bears. In the epic Ramayana, Jambavantha helped Rama find his wife Sita and fight her abductor, Ravana. It is he who makes Hanuman realize his immense capabilities and encourages him to fly across the ocean to search for Sita in Lanka.

Griddha

• Jatayu, son of Aruṇa and nephew of Garuda. A demi-god who has the form of a vulture that tries to rescue Sita from Ravana. Jatayu fought valiantly with Ravana, but as Jatayu was very old, Ravana soon got the better of him. As Rama and Lakshmana chanced upon the stricken and dying Jatayu in their search for Sita, he informs them of the direction in which Ravana had gone.

• Sampati, son of Aruna, brother of Jatayu. Sampati's role proved to be instrumental in the search for Sita.

Rakshasa

• Vibhishana, youngest brother of Ravana. He was against the abduction of Sita and joined the forces of Rama when Ravana refused to return her. His intricate knowledge of Lanka was vital in the war and he was crowned king of Lanka by Rama after the fall of Ravana.

Foes Of Rama

Rakshasas

• Ravana, a Rakshasa, is the king of Lanka. He was the son of a sage named Vishrava and daitya princess Kaikesi. After performing severe penance for ten thousand years he received a boon from the creator-god Brahma: he could henceforth not be killed by gods, demons, or spirits. He is portrayed as a powerful demon king who disturbs the penances of rishis. Vishnu incarnates as the human Rama to defeat him, thus circumventing the boon given by Brahma.

• Indrajit or Meghnadha, the eldest son of Ravana who twice defeated Rama and Lakshmana in battle, before succumbing to Lakshmana. An adept of the magical arts, he coupled his supreme fighting skills with various stratagems to inflict heavy losses on Vanara army before his death.

• Kumbhakarna, brother of Ravana, famous for his eating and sleeping. He would sleep for months at a time and would be extremely ravenous upon waking up, consuming anything set before him. His monstrous size and loyalty made him an important part of Ravana's army. During the war, he decimated the Vanara army before Rama cut off his limbs and head.

• Shurpanakha, Ravana's demoness sister who fell in love with Rama and had the magical power to take any form she wanted. Lakshmana cut off Shurpanakha's nose when she tried to hurt Sita angered by Rama's refusal of her proposal of marriage. It is she who asked Ravana to abduct Sita as revenge for her insult.

• Subahu (Sanskrit: सुबाहु Subāhu, Tamil: சுபாகு Cupāku, Kannada: ಸುಬಾಹು, Thai: Sawahu), is a rakshasa character in the Ramayana. He and his mother, Tataka, took immense pleasure in harassing the munis of the jungle, especially Vishvamitra, by disrupting their yajnas with rains of flesh and blood.[22] Vishvamitra approached Dasharatha for help in getting rid of these pestilences. Dasharatha obliged by sending two of his sons, Rama and Lakshmana, to the forest with Vishvamitra, charging them to protect both the sage and his sacrificial fires.[citation needed] When Subahu and Maricha again attempted to rain flesh and blood on the sage's yajna, Subahu was killed by Rama.[23] Maricha escaped to Lanka. He was later killed by Rama when he took the form of a deer.

Neutral

Vanara

• Vali, was king of Kishkindha, husband of Tara, a son of Indra, elder brother of Sugriva and father of Angada. Bali was famous for the boon that he had received, according to which anyone who fought him in single-combat lost half his strength to Vali, thereby making Vali invulnerable to any enemy. He was killed by Rama, an Avatar of Vishnu. However, he was not an enemy of Rama. He was killed by Rama because Vali had fought with his brother Sugriva after some misunderstanding, who was a loyal ally of Rama.

Rakshasa

• Viswashrava, was the son of Pulastya and the grandson of Brahma, the Creator, and a powerful Rishi as described in the great Hindu scripture epic Ramayana of Ancient India. A scholar par excellence, he earned great powers through Tapasya, which in turn, earned him great name and fame amongst his fellow Rishis. Bharadwaja, in particular, was so impressed with Viswashrava that he gave him his daughter, Ilavida, in marriage. Ilavida bore Viswashrava a son, Kubera, the Lord of Wealth and the original ruler of Lanka.[24] In addition to Ravana, Viswashrava fathered Vibhishana, Kumbakarna and a daughter, Shurpanakha, through Kaikesi. He is said to have disowned his demonic family after witnessing Ravana's disrespectful treatment of his older brother, Kubera and returned to his first wife, Ilavida.[citation needed] According to the Mahabharata, however, Viswashrava's younger children were born as a result of a falling-out with his eldest: Kubera tried to placate his father by giving him three Rakshasis (two of whom, Raka and Pushpotkata/Pushpotata, seem to be Kaikesi's paternal half-sisters) and in due course Viswashrava impregnated all three of them. Pushpotata gave birth to Ravana and later to Kumbhakarna, Malini bore Vibhishana, and Raka had the unpleasant and unsociable twins Khara and Shurpanakha.[25]

Synopsis

Bala Kanda

Main article: Bala Kanda

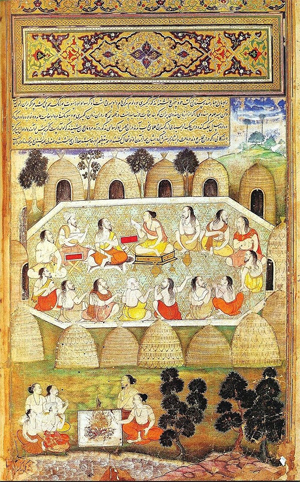

The marriage of the four sons of Dasharatha with the four daughters of Siradhvaja Janaka and Kushadhvaja. Rama and Sita, Lakshmana and Urmila, Bharata and Mandavi and Shatrughna with Shrutakirti.

This Sarga (section) details the stories of Rama's childhood and events related to the time-frame. Dasharatha was the King of Ayodhya. He had three wives: Kaushalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra. He was childless for a long time and anxious to have an heir, so he performs a fire sacrifice known as Putra-kameshti Yajna. As a consequence, Rama was first born to Kaushalya, Bharata was born to Kaikeyi, Lakshmana and Shatrughna were born to Sumitra. These sons are endowed, to various degrees, with the essence of the Supreme Trinity Entity Vishnu; Vishnu had opted to be born into mortality to combat the demon Ravana, who was oppressing the gods, and who could only be destroyed by a mortal. The boys were reared as the princes of the realm, receiving instructions from the scriptures and in warfare from Vashistha. When Rama was 16 years old, sage Vishwamitra comes to the court of Dasharatha in search of help against demons who were disturbing sacrificial rites. He chooses Rama, who is followed by Lakshmana, his constant companion throughout the story. Rama and Lakshmana receive instructions and supernatural weapons from Vishwamitra and proceed to destroy Tataka and many other demons.

Janaka was the King of Mithila. One day, a female child was found in the field by the King in the deep furrow dug by his plough. Overwhelmed with joy, the King regarded the child as a "miraculous gift of God". The child was named Sita, the Sanskrit word for furrow. Sita grew up to be a girl of unparalleled beauty and charm. The King had decided that who ever could lift and wield a heavy bow, presented to his ancestors by Shiva, could marry Sita. Sage Vishwamitra takes Rama and Lakshmana to Mithila to show the bow. Then Rama desires to lift it and goes on to wield the bow and when he draws the string, it broke.[26] Marriages were arranged between the sons of Dasharatha and daughters of Janaka. Rama marries Sita, Lakshmana to Urmila, Bharata to Mandavi and Shatrughna to Shrutakirti. The weddings were celebrated with great festivity in Mithila and the marriage party returns to Ayodhya.

Ayodhya Kanda

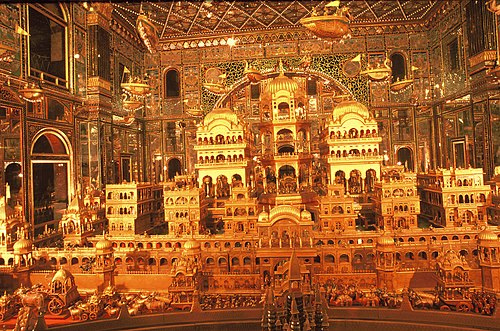

Gold carving depiction of the legendary Ayodhya at the Ajmer Jain temple.

After Rama and Sita have been married, an elderly Dasharatha expresses his desire to crown Rama, to which the Kosala assembly and his subjects express their support. On the eve of the great event, Kaikeyi – her jealousy aroused by Manthara, a wicked maidservant – claims two boons that Dasharatha had long ago granted her. Kaikeyi demands Rama to be exiled into the wilderness for fourteen years, while the succession passes to her son Bharata. The heartbroken king, constrained by his rigid devotion to his given word, accedes to Kaikeyi's demands. Rama accepts his father's reluctant decree with absolute submission and calm self-control which characterizes him throughout the story. He is joined by Sita and Lakshmana. When he asks Sita not to follow him, she says, "the forest where you dwell is Ayodhya for me and Ayodhya without you is a veritable hell for me." After Rama's departure, King Dasharatha, unable to bear the grief, passes away. Meanwhile, Bharata, who was on a visit to his maternal uncle, learns about the events in Ayodhya. Bharata refuses to profit from his mother's wicked scheming and visits Rama in the forest. He requests Rama to return and rule. But Rama, determined to carry out his father's orders to the letter, refuses to return before the period of exile.

Rama leaving for fourteen years of exile from Ayodhya.

Aranya Kanda

Main article: Aranya Kanda

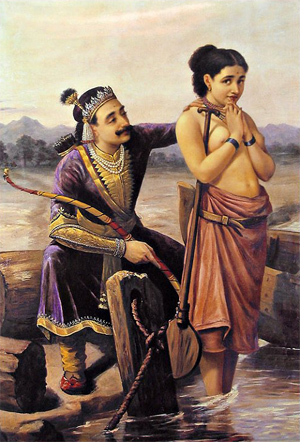

Ravana fights Jatayu as he carries off the kidnapped Sita. Painting by Raja Ravi Varma

After thirteen years of exile, Rama, Sita and Lakshmana journey southward along the banks of river Godavari, where they build cottages and live off the land. At the Panchavati forest they are visited by a rakshasi named Shurpanakha, sister of Ravana. She tries to seduce the brothers and, after failing, attempts to kill Sita. Lakshmana stops her by cutting off her nose and ears. Hearing of this, her brothers Khara and Dushan organise an attack against the princes. Rama defeats Khara and his raskshasas.

When the news of these events reach Ravana, he resolves to destroy Rama by capturing Sita with the aid of the rakshasa Maricha. Maricha, assuming the form of a golden deer, captivates Sita's attention. Entranced by the beauty of the deer, Sita pleads with Rama to capture it. Rama, aware that this is the ploy of the demons, cannot dissuade Sita from her desire and chases the deer into the forest, leaving Sita under Lakshmana's guard.

After some time, Sita hears Rama calling out to her; afraid for his life, she insists that Lakshmana rush to his aid. Lakshmana tries to assure her that Rama cannot be hurt that easily and that it is best if he continues to follow Rama's orders to protect her. On the verge of hysterics, Sita insists that it is not she but Rama who needs Lakshman's help. He obeys her wish but stipulates that she is not to leave the cottage or entertain any stranger. He draws a chalk outline, the Lakshmana rekha, around the cottage and casts a spell on it that prevents anyone from entering the boundary but allows people to exit. With the coast finally clear, Ravana appears in the guise of an ascetic requesting Sita's hospitality. Unaware of her guest's plan, Sita is tricked into leaving the rekha and is then forcibly carried away by Ravana.[27]

Jatayu, a vulture, tries to rescue Sita, but is mortally wounded. At Lanka, Sita is kept under the guard of rakshasis. Ravana asks Sita to marry him, but she refuses, being eternally devoted to Rama. Meanwhile, Rama and Lakshmana learn about Sita's abduction from Jatayu and immediately set out to save her. During their search, they meet Kabandha and the ascetic Shabari, who direct them towards Sugriva and Hanuman.

Kishkindha Kanda

A stone bas-relief at Banteay Srei in Cambodia depicts the combat between Vali and Sugriva (middle). To the right, Rama fires his bow. To the left, Vali lies dying.

Kishkindha Kanda is set in the ape (Vanara) citadel Kishkindha. Rama and Lakshmana meet Hanuman, the biggest devotee of Rama, greatest of ape heroes and an adherent of Sugriva, the banished pretender to the throne of Kishkindha. Rama befriends Sugriva and helps him by killing his elder brother Vali thus regaining the kingdom of Kishkindha, in exchange for helping Rama to recover Sita.

However Sugriva soon forgets his promise and spends his time enjoying his newly gained power. The clever former ape queen Tara (wife of Vali) calmly intervenes to prevent an enraged Lakshmana from destroying the ape citadel. She then eloquently convinces Sugriva to honour his pledge. Sugriva then sends search parties to the four corners of the earth, only to return without success from north, east and west. The southern search party under the leadership of Angada and Hanuman learns from a vulture named Sampati (elder brother of Jatayu), that Sita was taken to Lanka.

Sundara Kanda

Main article: Sundara Kanda

Ravana is meeting Sita at Ashokavana. Hanuman is seen on the tree.

Sundara Kanda forms the heart of Valmiki's Ramayana and consists of a detailed, vivid account of Hanuman's adventures. After learning about Sita, Hanuman assumes a gargantuan form and makes a colossal leap across the sea to Lanka. On the way he meets with many challenges like facing a Gandharva kanya who comes in the form of a demon to test his abilities. He encounters a mountain named Mainakudu who offers Hanuman assistance and offers him rest. Hanuman refuses because there is little time remaining to complete the search for Sita.

After entering into Lanka, he finds a demon, Lankini, who protects all of Lanka. Hanuman fights with her and subjugates her in order to get into Lanka. In the process Lankini, who had an earlier vision/warning from the gods therefore knows that the end of Lanka nears if someone defeats Lankini. Here, Hanuman explores the demons' kingdom and spies on Ravana. He locates Sita in Ashoka grove, where she is being wooed and threatened by Ravana and his rakshasis to marry Ravana. Hanuman reassures Sita, giving Rama's signet ring as a sign of good faith. He offers to carry Sita back to Rama; however, she refuses and says that it is not the dharma, stating that Ramyana will not have significance if Hanuman carries her to Rama – "When Rama is not there Ravana carried Sita forcibly and when Ravana was not there, Hanuman carried Sita back to Rama". She says that Rama himself must come and avenge the insult of her abduction.

Hanuman then wreaks havoc in Lanka by destroying trees and buildings and killing Ravana's warriors. He allows himself to be captured and delivered to Ravana. He gives a bold lecture to Ravana to release Sita. He is condemned and his tail is set on fire, but he escapes his bonds and leaping from roof to roof, sets fire to Ravana's citadel and makes the giant leap back from the island. The joyous search party returns to Kishkindha with the news.

Yuddha Kanda

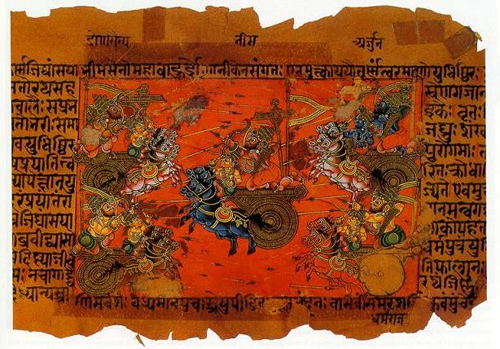

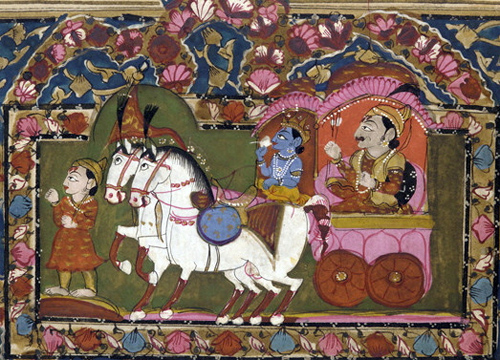

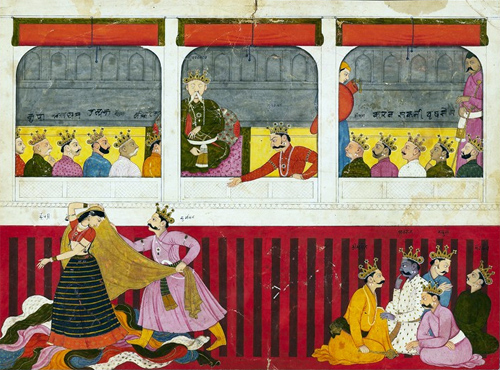

The Battle at Lanka, Ramyana by Sahibdin. It depicts the monkey army of the protagonist Rama (top left, blue figure) fighting Ravana—the demon-king of the Lanka—to save Rama's kidnapped wife, Sita. The painting depicts multiple events in the battle against the three-headed demon general Trishira, in bottom left. Trishira is beheaded by Hanuman, the monkey-companion of Rama.

Also known as Lanka Kanda, this book describes the war between the army of Rama and the army of Ravana. Having received Hanuman's report on Sita, Rama and Lakshmana proceed with their allies towards the shore of the southern sea. There they are joined by Ravana's renegade brother Vibhishana. The apes named Nala and Nila construct a floating bridge (known as Rama Setu)[28] across the sea, using stones that floated on water because they had Rama's name written on them. The princes and their army cross over to Lanka. A lengthy war ensues. During a battle, Ravana's son Indrajit hurls a powerful weapon at Lakshmana, who is badly wounded. So Hanuman assumes a gigantic form and flies from Lanka to the Himalayas. Upon reaching Mount Sumeru, Hanuman was unable to identify the herb that could cure Lakshmana and so decided to bring the entire mountain back to Lanka. Eventually, the war ends when Rama kills Ravana. Rama then installs Vibhishana on the throne of Lanka.

On meeting Sita, Rama agrees to Sita's request[29] to undergo an Agni Pariksha (test of fire) to prove her chastity, as he wants to get rid of the rumors surrounding her purity. When Sita plunges into the sacrificial fire, Agni, lord of fire raises Sita, unharmed, to the throne, attesting to her innocence. The episode of Agni Pariksha varies in the versions of Ramayana by Valmiki and Tulsidas. In Tulsidas's Ramacharitamanas, Sita was under the protection of Agni (see Maya Sita) so it was necessary to bring her out before reuniting with Rama.

Uttara Kanda

Sita with Lava and Kusha

It conjectures Rama's reign of Ayodhya, the birth of Lava and Kusha, the Ashvamedha yajna and last days of Rama. At the expiration of his term of exile, Rama returns to Ayodhya with Sita, Lakshmana, and Hanuman, where the coronation is performed. On being asked to prove his devotion to Rama, Hanuman tears his chest open and to everyone's surprise, there is an image of Rama and Sita inside his chest. Rama rules Ayodhya and the reign is called Ram-Rajya (a place where the common folk is happy, fulfilled, and satisfied).

This book (kanda) is not considered to be a part of the original epic but instead a later addition to the earliest layers of the Valmiki Ramayana and is considered to be highly interpolated. In this book, as time passes in the reign of Rama, spies start getting rumours that people are questioning Sita's purity as she stayed in the home of another man for almost a year without her husband. The common folk start gossiping about Sita and question Rama's decision to make her Queen. Rama is extremely distraught on hearing the news, but finally tells Lakshmana that the purity of the Queen of Ayodhya has to be above any gossip and rumour. Ram instructs him to take Sita to a forest outside Ayodhya and leave her there with a heavy heart. Lakshmana reluctantly drops Sita in a forest for another exile.

Sita finds refuge in Sage Valmiki's ashram, where she gives birth to twin boys, Lava and Kusha. Meanwhile, Rama conducts an Ashwamedha yajna (A holy declaration of the authority of the king) and in absence of Sita places a golden statue of Sita. Lava and Kusha capture the horse (sign of the yajna) and defeat the whole army of Ayodhya which come to protect the horse. Later on, both the brothers defeat Lakshmana, Bharata (Ramayana), Shatrughan and other warriors and take Hanuman as prisoner. Finally Rama himself arrives and defeats the two mighty brothers. Valmiki updates Sita about this development and advises both the brothers to go to Ayodhya and tell the story of Sita's sacrifice to the common folk. Both brothers arrive at Ayodhya but face many difficulties while convincing the people. Hanuman helps both the brothers in this task. At one point, Valmiki brings Sita forward. Seeing Sita, Rama is teary eyed and realises that Lava and Kusha are his own sons. Again complicit Nagarsen (one of the primaries who instigated the hatred towards Sita) challenges Sita's character and asks her to prove her purity. Sita is overflown with emotions and decides to go back to Mother Earth from where she emerged. She says that, "If I am pure, this earth will open and swallow me whole." At that very moment, the earth opens up and swallows Sita. Rama rules Ayodhya for many years and finally takes Samadhi into Sarayu river along with his three brothers and leaves the world. He goes back to Vaikuntha in his Vishnu form (Lakshman as Shesh Naga, Bharat as his conch and Shatrughan as the Sudarshan Chakra) and meets Sita there who by then assumed the form of Lakshmi.

Versions

See also: Versions of Ramayana

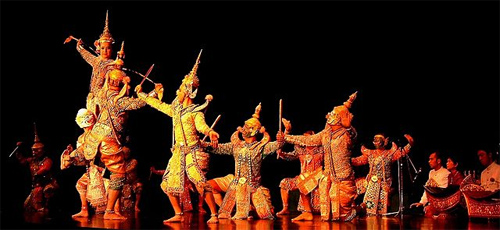

The epic story of Ramyana was adopted by several cultures across Asia. Shown here is a Thai historic artwork depicting the battle which took place between Rama and Ravana.

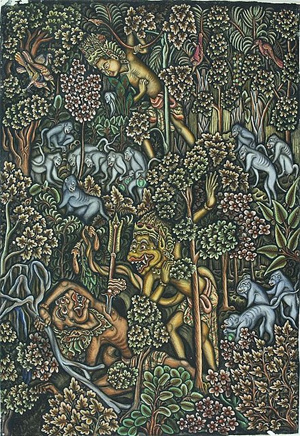

Relief with part of the Ramayana epic, shows Rama killed the golden deer that turn out to be the demon Maricha in disguise. Prambanan Trimurti temple near Yogyakarta, Java, Indonesia.

As in many oral epics, multiple versions of the Ramayana survive. In particular, the Ramayana related in north India differs in important respects from that preserved in south India and the rest of southeast Asia. There is an extensive tradition of oral storytelling based on Ramayana in Indonesia, Cambodia, Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Laos, Vietnam and Maldives.

India

There are diverse regional versions of the Ramayana written by various authors in India. Some of them differ significantly from each other. A West Bengal manuscript from the 6th century presents the epic without two of its kandas. During the 12th century, Kamban wrote Ramavataram, known popularly as Kambaramayanam in Tamil, but references to Ramayana story appear in Tamil literature as early as 3rd century CE. A Telugu version, Ranganatha Ramayanam, was written by Gona Budda Reddy in the 14th century. The earliest translation to a regional Indo-Aryan language is the early 14th century Saptakanda Ramayana in Assamese by Madhava Kandali. Valmiki's Ramayana inspired Sri Ramacharit Manas by Tulsidas in 1576, an epic Awadhi (a dialect of Hindi) version with a slant more grounded in a different realm of Hindu literature, that of bhakti; it is an acknowledged masterpiece of India, popularly known as Tulsi-krita Ramayana. Gujarati poet Premanand wrote a version of the Ramayana in the 17th century. Other versions include Krittivasi Ramayan, a Bengali version by Krittibas Ojha in the 15th century; Vilanka Ramayana by 15th century poet Sarala Dasa[30] and Jagamohana Ramayana (also known as Dandi Ramayana) by 16th century poet Balarama Dasa, both in Odia; a Torave Ramayana in Kannada by 16th-century poet Narahari; Adhyathmaramayanam, a Malayalam version by Thunchaththu Ramanujan Ezhuthachan in the 16th century; in Marathi by Sridhara in the 18th century; in Maithili by Chanda Jha in the 19th century; and in the 20th century, Rashtrakavi Kuvempu's Sri Ramayana Darshanam in Kannada and Srimad Ramayana Kalpavrikshamu in Telugu by Viswanatha Satyanarayana who received Jnanapeeth award for this work.

There is a sub-plot to the Ramayana, prevalent in some parts of India, relating the adventures of Ahiravan and Mahi Ravana, evil brother of Ravana, which enhances the role of Hanuman in the story. Hanuman rescues Rama and Lakshmana after they are kidnapped by the Ahi-Mahi Ravana at the behest of Ravana and held prisoner in a cave, to be sacrificed to the goddess Kali. Adbhuta Ramayana is a version that is obscure but also attributed to Valmiki – intended as a supplementary to the original Valmiki Ramayana. In this variant of the narrative, Sita is accorded far more prominence, such as elaboration of the events surrounding her birth – in this case to Ravana's wife, Mandodari as well as her conquest of Ravana's older brother in the Mahakali form.t