by Lynn Hirschberg

Vanity Fair - September, 1992.

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Are Courtney Love, lead diva of the postpunk band Hole, and her husband, Nirvana heartthrob Kurt Cobain, the grunge John and Yoko? Or the next Sid and Nancy? Lynn Hirschberg reports.

Courtney Love is late. She’s nearly always late, and not just ten, fifteen minutes late, but usually more like an hour past the time she’s said she’ll be someplace. She’s late for band rehearsals, she was late when she used to strip, she was even an hour late for a meeting with a record-company executive who wanted to sign her band, Hole. Courtney assumes that people will wait. She assumes that they will forgive her as they stare at the clock and stare at the door and wonder where the hell she is. And they do forgive her. Until they can’t stand it anymore and then they get mad, fed up, and move on. But by that time Courtney is gone... she’s off keeping someone else waiting.

When she does show up, she shows up. When you’re an hour late, you can really make an entrance. She’s tall and big-boned and her shoulder-length hair is cut like a mop and dyed yellow-blond. The dark roots show on purpose – nothing about Courtney is an accident ... and today she’s attached a plastic hair clip in the shape of a bow to a few strands.

She’s wearing black stockings with runs in them, a vintage dress that’s a size too small, and a pair of black clogs. Her skin, which has been heavily Pan-Caked and powdered to cover an outbreak of acne, is pasty-white, and her lips are painted bright red. She has beautiful round blue-green eyes, which she has carefully made up, but the focus is on her mouth. She’s all lipstick.

And talk. From the moment Courtney sits down at a table in City, a restaurant near her home in Los Angeles, the verbal pyrotechnics begin. You get the sense that she has a monologue going twenty-four hours a day and that sometimes she includes others. When she’s not talking, she doesn’t seem to be listening exactly but, rather, absorbing: Who is this person? What is his context? What can I learn/get from him? are the thoughts coursing through her brain. With Courtney, it’s not so much scheming as it is focus. She has always known what she wanted and what she wanted was to be a star. More precisely, Courtney always thought she was a star. She was just waiting for everyone else to wake up.

It looks as if, after a few false starts ... an acting career that didn’t quite take, some stints in other bands that didn’t work out ... Courtney is having her moment. She and Hole were just signed to a million-dollar record deal; she is married to Kurt Cobain, the lead singer of Nirvana, and within the realm of the alternative-music scene, Courtney is now regarded as a train-wreck personality: she may be awful, but you can’t take your eyes off her.

Her timing is excellent: in the wake of the huge success of Nirvana, an extremely talented rock band from Seattle that surprised everyone in the industry by selling (so far) seven million records worldwide, there has been a frenzy to sign other bands in the punk-grunge-underground mode. The music ranges from almost pop to loud thrashing ... the only real unifying link is that most of the bands are on independent labels and appeal to college audiences. "No one can get a seat on a plane to Seattle or Portland now." says Ed Rosenblatt, president of Geffen Records, Nirvana’s label. "Every flight is booked by A&R people out to find the next Nirvana."

Last August, Hole, which is much more extreme and less melodic than Nirvana, released Pretty on the Inside on Caroline Records, an independent that is a subsidiary of Virgin. The record is intensely difficult to listen to—Courtney’s singing is a mix of shouting, screeching, and rasping ... but her songwriting, which has been compared to Joni Mitchell’s, is powerful. "‘Pretty on the Inside,’" writes Elizabeth Wurtzel in The New Yorker, "is such a cacophony ... full of such grating, abrasive, and unpleasant sludges of noise... that very few people are likely to get through it once, let alone give it the repeated listenings it needs for you to discover that it’s probably the most compelling album to have been released in 1991."

Courtney’s postfeminist stance (she has the power—she just wants to be loved) echoes throughout her songs. Her chosen topics—rape and abortion, to name two—are extremely provocative. "Slit me open and suck my scars," she sings about sex. "Don’t worry baby, you will never stink so bad again," she intones about a botched abortion. In her strongest song, "Doll Parts," she turns introspective: "I want to be the girl with the most cake / He only loves the things because he loves to see them break / I think it’s true ... I am beyond fake / Someday you will ache like I ache."

Even before Nirvana’s massive success, Hole was lumped with Babes in Toyland, L7, the Nymphs, and other female led underground groups. Although these bands were quite different from one another, and wildly competitive, they were all dubbed "foxcore." And when Nirvana’s album Nevermind started to sell like mad, the so-called foxcore bands suddenly seemed commercially viable. "There’s a pre-Nirvana record-industry perception of this kind of music," says Gary Gersh, the Geffen Records A&R person who signed Nirvana. "And there’s a post-Nirvana record-industry perspective. But if you’re out there and trying to sign the new Nirvana, you’re chasing your tail. The game is not finding the next Nirvana, because there won’t be a next Nirvana."

It is somehow appropriate that Madonna’s new company, Maverick, was the first to be interested in signing Courtney Love to a major record deal. In mid-1991, Guy Oseary, an enthusiastic nineteen-year-old who was working for Madonna and her manager, Freddy De Mann, at their then unnamed company, told his bosses about Hole. He also contacted Courtney’s lawyer, Rosemary Carroll, and Hole-mania began. "Courtney had been orchestrating this game plan from the beginning," says Carroll. "She was always very aware of the business, of her place in the business."

Courtney claims she never wanted to sign with Maverick. "Freddy would have me riding on elephants," she says. "They don’t know what I am. For them, I’m a visual, period." Madonna’s presence worried her even more: she did not want to share the spotlight with the premier blonde goddess of the last decade. "Madonna’s interest in me was kind of like Dracula’s interest in his latest victim."

But Courtney, who is nothing if not shrewd, knew that one offer could spur other offers. Besides, she had another ace to play: by late ‘91 she was dating Kurt Cobain. When Hole went to England, she wasn’t shy about either Madonna’s interest or her new boyfriend. She gave lots of interviews and the notoriously fickle British music magazines, who adored her grunge-rock sound and her torn thirties tea dresses, proclaimed her their new genius. "The British tabloids called me ‘leggy’ and ‘stunning,’" she recalls. "The best article was about Madonna. It had a really big picture of me as a blonde and a really small picture of her as a brunette. I cut that one out."

For his part, Oseary, who saw Courtney and Hole as his private find, was shocked. "The stories in the English press went, ‘Madonna doesn’t have AIDS and she wants to sign Hole,’" he recalls, sounding rather exasperated. "From then on, it was ‘Madonna’s Hole.’ ‘Madonna’s Hole.’ Suddenly, we’re just one of the bidders. At Hole’s next show, thirteen A&R people were there!"

So it began—the first-ever bidding war over an unsigned female band. (In the record business, independent labels are not considered contenders—until you’re on a major label you’re unsigned.) It wasn’t clear whether or not most of the bidders liked, or even knew, Hole’s music—it was the magic combination of Madonna’s interest, Kurt Cobain’s interest, and the strength of Courtney’s personality. In any case, Clive Davis, president of Arista Records, reportedly offered a million dollars to sign the band. Rick Rubin, head of Def American, was interested, but he and Courtney clashed when they met. She had similar difficulties with Jeff Ayeroff at Virgin. "Now, Kurt," she exclaims, "is able to go into Capitol, go into a meeting, decide he doesn’t like it halfway through, walk out on the guys mid-sentence, and everyone goes, 'There goes Kurt. He’s so moody. Nirvana’s great.' But I go in and spend three hours with Jeff Ayeroff and tell him more about punk rock than he ever knew. I give him quality time, but, I’m sorry, I don’t want to be on his label and he gets a boner about it and calls me a bitch."

In the end, she signed with Gary Gersh at Geffen, the same label as Nirvana. "We didn’t make the deal because she is married to Kurt Cobain," says Ed Rosenblatt. "But it is a little weird. Hole is a band who we happen to believe in and, oh, by the way, she’s married to..."

Courtney’s deal, worth around a million dollars, is bigger and better than her husband’s. She and Carroll insisted on that. "I got excellent, excellent contractual things," she boasts. "I made them pull out Nirvana’s contract, and everything on there, I wanted more. I’m up to half a million for my publishing rights and I’m still walking. If those sexist assholes want to think that me and Kurt write songs together, they can come forward with a little more." She pauses. "No matter what label I’m on, I’m going to be his wife," she says. "I’m enough of a person to transcend that."

Probably. But in the circles she travels in, Kurt Cobain is regarded as a holy man. Courtney, meanwhile, is viewed by many as a charismatic opportunist. There have been rampant reports about the couple’s drug problems, and many believe she introduced Cobain to heroin. They are expecting a baby this month, and even the most tolerant industry insiders fear for the health of the child. "It is appalling to think that she would be taking drugs when she knew she was pregnant," says one close friend. "We’re all worried about that baby."

"Courtney and Kurt are the nineties, much more talented version of Sid and Nancy," says one executive. "She’s going to be famous and he already is. But unless something happens, they’re going to self-destruct. I know they’re both going to be big stars. I just don’t want to be a part of it."

Courtney has heard all this before and, in a perverse way, she thrives on it. "I heard a rumor that Madonna and I were shooting heroin together," she says rather gleefully, lighting up a cigarette. "I’ve heard I had live sex onstage and that I’m H.I.V.-positive."

Courtney laughs. None of these statements is true, although the live-sex thing is a very persistent rumor. "Now," she continues, balancing her cigarette on the edge of the ashtray. "I get a chance to prove myself. And if I do, I do. If I don’t—hey, I married a rich man!"

She drags for dramatic effect. She’s joking and, then again, she isn’t. Audacity is one of the keys to her charm. "You know, I just can’t find makeup that stays on in the summer," she says, abruptly changing the subject. Courtney stamps out her cigarette, rummages through her purse, and heads off to the bathroom.

"Only about a quarter of what Courtney says is true," says Kat Bjelland, the leader of Babes in Toyland. "But nobody usually bothers to decipher which are the lies. She’s all about image. And that’s interesting. Irritating, but interesting."

When it comes to biographical information, Courtney is hard to track. She says she was born in San Francisco in 1966 (that date seems off—she is probably older than twenty-six, although not much), her father was involved with the Grateful Dead, and her mother, who was from a wealthy family, was a follower of various gurus. (She no longer speaks to her father, and her mother, who has married several times since, is closer to Courtney’s four half-siblings, one of whom is a Rhodes scholar.)

Courtney hated school and moved around quite a lot: from boarding school in New Zealand to a Quaker school in Australia to where she ended up—Oregon. At twelve, she stole a Kiss T-shirt from Woolworth’s and was sent to a juvenile detention center. "To be quite honest." she recalls, "I got into it. I was very semiotic about my delinquency. I studied it. I learned a lot. I’d grown up with no discipline and I learned a lot about denial. It did not have an adverse effect on me."

After three years, around 1981, she was out and living on a small trust fund. She had pretty much decided that music would be her world. She also began stripping— an occupation that has, off and on, supported her for most of her adult life. "I didn’t want to sell drugs," she explains. "I didn’t want to steal cars. I didn’t want to be a prostitute. So I stripped.

"And I was fat then," she continues. "You can be fat and strip. I’d strip at Jumbo’s Clown Room. Or I’d work in the day at the Seventh Veil. I didn’t have a gimmick. I see girls now who are trying to be alternative. They won’t make a dime. You’ve got to have white pumps, pink bikini, fuckin’ hairpiece, pink lipstick. Gold and tan and white. If you even try and slip a little of yourself in there you won’t make any money."

Through the classifieds in a punk fanzine called Maximum Rock N Roll, Courtney had begun corresponding with Jennifer Finch, a kindred spirit who was living in L.A. "I came and visited her," Courtney says, "and entered the glamorous world of ‘extra’ work."

Jennifer had been working part-time as punk-rock color on TV shows like Quincy and CHiPs, and she brought Courtney along. "I met a lot of people through that," she says. One of those people was Alex Cox, who was about to direct Sid and Nancy. "All the punk-rock extras went up for parts in Sid and Nancy," Courtney recalls. "He met me and he put his arm around me and said the most subversive thing he could think of was foisting me on the world. That was back when I was really overweight, too. But I wasn’t scared. I wanted to act ever since Tatum O’NeaI won the Oscar."

She was cast as Nancy Spungen’s best friend, and then Cox wrote Straight to Hell, an incomprehensible spaghetti Western, for her. There were rumors that the two were lovers, but Courtney vehemently denies any romantic involvement. "I was sexless," she says. "People say we were a couple because that’s how they explain his interest in me. During that time, I did not sleep with anybody. I was fat and when you’re fat you can’t call the shots. It’s not you with the power."

Following Straight to Hell, Courtney decided to briefly abandon her musical aspirations and concentrate on acting. She took the $20,000 that she’d been paid, moved out of Jennifer’s house, rented an apartment, and bought a pink Chanel suit. She was taking the bus – she still doesn’t know how to drive, despite having lived in L.A. for ten years – but she was well dressed.

"I didn’t quite pull it off," she says. "A friend went to a party and told Jennifer, ‘Courtney was wearing Chanel and she had a glass of champagne in her hand, but her makeup was exactly the same.’ It wasn’t quite right. I had this publicist who was obsessed with Madonna and obsessed with me and she decided to make me into a star. I just couldn’t pull it off. I’d get zits."

It occurred to Courtney that you could have acne and still be a rock star, so she moved back to Portland, slimmed down, and started singing in bands, including Faith No More, which has gone on to tour with Guns N’ Roses and Metallica. She met Kat Bjelland, and in ‘84 or ‘85. Courtney and Jennifer and Kat moved to San Francisco and started a band called Sugar Baby Doll. "We wore pinafores and played twelve-string Rickenbackers," she says. "It was a disaster." It wasn’t a punk band—Sugar Baby Doll was softer, sweeter. "Jennifer and I were not into it," recalls Kat. "We wanted to play punk rock. Courtney thought we were crazy. She hated punk then."

In the alternative world, integrity and credentials are everything—and Courtney is viewed by most as a late convert to the world of punk. "I was New Wave more than hard-core," she admits. "I thought the whole punk scene was really ugly and unglamorous and I needed it to be glamorous. I’m into it now, but back then I’d go to Black Flag [a seminal L.A. punk band] shows and refuse to go in. It was just all these boys killing each other."

After the San Francisco debacle, she moved to Minneapolis and played briefly with Kat’s new band, Babes in Toyland. (Jennifer was back in LA, forming her band, L7.) She and Kat clashed, and she went to Alaska to strip. Then she moved to Portland briefly, and by 1989 she was back in Los Angeles. "I just couldn’t take it anywhere else," she explains. "Minneapolis was so fucking unpretentious. Everyone has a flannel collection and is in a band named after a welding instrument."

She put an ad in the Recycler ("I want to start a band. My influences are Big Black, Stooges, Sonic Youth and Fleetwood Mac") and stripped to pay the rent. "I Worked at Star Strip," she says. "The girls in that place are superconstructed. They’re a little classy. Three of them had fucked Axl [Rose]." Soon she put together Hole and started to rehearse in earnest.

"The first time I saw her onstage, she was dressed like a soiled debutante." says Rosemary Carroll, Courtney’s lawyer. ‘‘Her dress was ripped and she was a mess except for a perfectly pressed huge pink bow on the back of her dress. She was riveting to watch. Courtney had a presence and a power that was fascinating."

Hole played around L.A., but they weren’t discovered until they went to England in late 1991. Courtney may have been jumping on the foxcore/alternative-band wagon in America (although she would claim otherwise), but in England she was perceived as an original. With her dirty baby-doll dresses and dark kinky songs, she was the U.K. music-press pinup of choice. "I thought they’d be terrified of me," she says. "This loud American woman. But it worked! We sold a lot of records."

And they came back to a buzz in the States. By then, she was together with Kurt and the Madonna thing happened and everything was falling into place. "It wasn’t surprising," Courtney says. "I mean, I wasn’t surprised. I always knew."

It’s about seven P.M. on a balmy night in early summer and Courtney is knocking on the door of her apartment. She has lost her key or forgot her key or can’t find her key. Whatever. "KU-RT," she singsongs. "Come to the door."

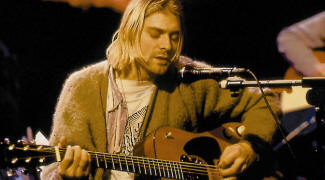

After a short wait, he opens it. "Where’s your key?" he asks, looking as if he’s just woken up. Kurt is wearing pajama bottoms, is bare-chested, and has a sparkly beaded bracelet on his wrist. He is small and very thin and has pale-white skin. His hair, which he’s dyed red and purple in the past, is now blond, and his eyes are very blue. His face is quite beautiful, almost delicate. Where Courtney projects strength, Kurt seems fragile. He looks as if he might break.

"God, it’s hot in here," Courtney says, marching into the apartment. Kurt explains that he’s turned the heat on—it feels around a hundred degrees in the living room. "I’m still cold," he says, slumping into an overstuffed armchair. He looks exhausted.

Their home, in the Fairfax area of L.A., is sparsely furnished. There are guitars in their open cases on the floor, and a Buddhist altar has been set up against one wall. Dead flowers sit in a vase next to a pair of those see-through body-anatomy dolls. In fact, there are dolls everywhere: infant dolls with china heads that Kurt is using in the next Nirvana video, a plastic doll that he found while on tour, and many, many toy monkeys. Painted on the fireplace, which is covered with candy hearts and heart-shaped candy boxes, are the scrawled words MY BEST FRIEND. "We had a fight last night," explains Courtney. "So I wrote that to remind him."

She continues the apartment tour, showing off a drawing that Kurt’s sister did, a photo of him at six with a drum, another doll, whose head is cracked open. In the kitchen, Courtney has taped lists all over the cabinets. "Kurt’s ex-girlfriend made these," she says. "I found them when I went through his stuff." She reads aloud from one: "1. Good Morning! 2. Will you fill up my car with unleaded gas. 3. Sweep kitchen floor. 4. Clean tub. 5. Go to Kmart. 6. Get one dollar in quarters." This last one seems to crack her up. "He never did any of that stuff."

The phone rings. Kurt has disappeared into the bedroom, and Courtney goes to answer it. "Hi, Dave," she says. It is Dave Grohl, the drummer in Nirvana. The band has been on hiatus for a few months and Dave is calling from Washington, D.C. "I’ll go get him," Courtney says, sounding more than slightly perturbed. She puts down the receiver. "Just call me Yoko Love," she say’s. "KU’-RT." Kurt curls up with the phone, and Courtney plops down on a legless sofa. She is wearing a green flowered dress that’s ripped along the bodice so that her bra is exposed. "They all hate me," she says. "Everyone just fucking hates my guts."

This may be true. Since Courtney and Kurt’s courtship began last year, she has reportedly antagonized Grohl and Chris Novoselic, the other two members of Nirvana. "Courtney always has a hidden agenda," says someone close to the band. "And Kurt doesn’t. He’s definitely being led."

While it’s difficult to determine Courtney’s ulterior motive with regard to Kurt, she does have mini-feuds galore. Her major complaint in terms of Nirvana seems to be with Novoselic’s wife, Shelli. Courtney's gripe is vague—something about Shelli’s making Kurt sleep in the hallway of their house. "I wouldn’t let her come to my wedding." Courtney says.

She definitely relishes her position as Mrs. Kurt Cobain. It was one of her goals, not something she left up to fate. The couple first met eight or so years ago in Portland. "Back then," she recalls, "we didn’t have an emotion towards each other. It was, like, ‘Are you coming over to my house?’ ‘Are you going to get it up?’ ‘Fuck you.’ That sort of thing."

By the time they met again. Kurt was a star and Courtney was much less casual in her approach. She realized that, when it comes to romance, aggressive behavior can be very appealing. "People say, ‘How did she get Kurt,’" says one friend. "Well, she asked. And she wouldn’t take no for an answer."

Courtney pursued him for months – got his number, called him, told interviewers that she had a crush on him. She even resorted to religion. "Courtney chanted for the coolest guy in rock ‘n’ roll – which, to her mind, was Kurt – to be her boyfriend," says Jimmy Boyle, a friend who works for the Def American. Finally, she persuaded an eager-to-please prospective manager to give her tickets (plane and concert) to a Nirvana show in Chicago.

"I was there in Chicago when they consummated their relationship," say’s Danny Goldberg, senior V.P. at Polygram and Nirvana’s (and now Hole’s) manager. "We chatted for a while and Courtney worked her way into the other room, where Kurt was. I didn’t see sparks, but they did go home together. That was in early October. They were married in February."

It wasn’t really quite that simple. Initially, Kurt had his doubts. Reportedly he had been too busy recording and then touring with Nirvana to focus much on romance. "Kurt is very smart," says one friend, "but he’s shy. A lot of people mistake that shyness for a lack of confidence, but he does know his own mind. When Courtney showed up I think he was attracted to her flamboyance. She was very sexual and I think she just took him over. He went on TV and said she was the best fuck in the world."

Still, there were problems. "He thought I was too demanding, attention-wise," Courtney says matter-of-factly. "He thought I was obnoxious. I had to go out of my way to impress him."

By the time he proposed ("I just knew he should ask me if he had any brains at all"), she was pregnant. The wedding was in Hawaii: Kurt, who once planned to wear a dress, wore pajamas, and Courtney wore ‘‘a white diaphanous item that had dry rot. It had been Frances Farmer’s in a movie." She signed a pre-nuptial agreement (her idea) and they did not go on a honeymoon. "Life is like a perennial honeymoon right now," she says. "I get to go to the bank machine every day."

All this would he perfect, except for the drugs. Twenty different sources throughout the record industry maintain that the Cobains have been heavily into heroin. Earlier this year, Kurt told Rolling Stone that he was not taking heroin, but Courtney presents another, extremely disturbing picture. "We went on a binge," she says, referring to a period last January when Nirvana was in New York to appear on Saturday Night Live. We did a lot of drugs. We got pills, and then we went down to Alphabet City and we copped some dope. Then we got high and went to S.N.L.. After that, I did heroin for a couple of months."

"It was horrible," recalls a business associate who was travelling with them at the time. "Courtney was pregnant and she was shooting up. Kurt was throwing up on people in the cab. They were both out of it."

Courtney has a long history with drugs. She loves Percodans ("They make me vacuum"), and has dabbled with heroin off and on since she was eighteen, once even snorting it in Room 101 of the Chelsea Hotel, where Nancy Spungen died. Reportedly, Kurt didn’t do much more than drink until he met Courtney. "He tried to be an alcoholic for a long time," she says. "But it didn’t sit right with him."

After their New York binge, it was suggested to Courtney that she have an abortion. She refused and, reportedly, had a battery of tests that indicated the fetus was fine. "She wanted to get off drugs," says Boyle. "I brought her herbs to ease the kick, so she wouldn’t freak out so badly. I was bringing stuff over to her house every day because it’s a whacked-out thing to do to a kid."

According in several sources, Courtney and Kurt went to separate detox hospitals in March. "After a few days, she left and went and got him," says one insider. "They never went back."

Whether or not they are using now is not clear. "It’s a sick scene in that apartment," says a close friend. "But lately, Courtney’s been asking for help."

She is definite about one thing: she wants the baby. And so does Kurt. In the living room is a painting he made using the sonogram of the fetus as a centerpiece. They know it’s a girl and have picked out a name: Frances Bean Cobain.

"Kurt’s the right person to have a baby with," Courtney continues. "We have money. I can have a nanny. The whole feminine experience of pregnancy and birth—I’m not into it on that level. But it was a bad time to get pregnant and that appealed in me." She smiles. "Besides, we need new friends."

This is a sly reference to Kurt’s phone call, which is winding down. "Dave is upset," Kurt says after hanging up. "So," Courtney says, "what do you want to do? Why don’t you start a new band without Chris [sic]?" Kurt pauses. He looks upset. "But I want Dave," he says. "He’s the best fucking drummer I know."

They are both silent a few minutes. Kurt looks so tried he seems to be asleep with his eyes open. Courtney suggests they go out to buy cigarettes. "Will I get hassled?" says Kurt, who, due to the popularity of Nirvana’s videos, is recognized everywhere. "Get used to it!" says Courtney. He shrugs ... it doesn’t look as if he wants to move an inch, much less miles into the world. "You’re such a grump," she says. It’s frustrating ... you marry a millionaire rock god and all he wants to do is stay home and mope. "We never do anything fun," Courtney whines. Kurt is silent. "O.K.," he says finally. "Where are they car keys?" As Courtney searches for them, Kurt heads off to the bedroom to put on a shirt. "You know, he drives really well," she says as she hunts through a pile of stuff. "He likes safety."

There’s just been an earthquake ... 6.1 on the Richter scale ... but Courtney and Kurt don’t notice. They are too busy shopping. Kurt is excited...this store, American Rag, which is huge and specializes in authentic vintage clothes mixed with clothes that are new but appear to be vintage, has an enormous collection of used jeans in very small sizes. He is making his way through the rack very, very slowly. "I got him to wear boxers," Courtney says, helping him to find his size. "You can’t believe how tacky he was, he wore bikinis. Colored. Just a tacky thing."

She gets impatient and heads off to inspect a rack of dresses. She is very specific about style. She tries to achieve what she terms the "Kinder-whore look," which seems to mean either ripped dresses from the thirties or one-size-too-small, velvet dresses from the sixties. Her hair and makeup remain consistent: white skin, red lips, blond hair with black roots. "It’s a good look," she explains. "It’s sexy, but you can sit down and say, ‘I read Camille Paglia.’"

Courtney is extremely possessive about this style statement...she is currently in a war with her erstwhile friend Kat Bjelland because of a borrowed velvet dress. Or, at least, that's what started it.

"Kat has stolen a lot front me," she says, hitting on one of her very favorite themes. "Dresses. Lyrics. Riffs. Guitars. Shoes. She even went after Kurt. That was the last straw. Because I put up with the lyric stealing. And I put up with her going to England first in a dress that I loaned her. Now I can’t wear those fucking dresses in England anymore."

Kat isn’t Courtney’s only target ... she’s convinced that nearly everyone in the music scene is either plundering her schtick or is just plain worthless. She hates Inger Lorre, the lead singer of the Nymphs; despises Pearl Jam, another terrific Seattle band ("They’re careerist and they go out with models"); is angry with Faith No More ("The new record is called Angel Dust – they stole that from me"); has quarreled with Jennifer Finch of L7 (more stolen lyrics); and is convinced Axl Rose is "an ass – and he also goes out with models."

And so on. Not surprisingly, she also has a few concerns about Madonna. "I didn’t want to get involved with her, because she’s a bad enemy to have," Courtney says, giving a navy dress a closer inspection. "I don’t want her to know anything about me, because she’ll steal what she can. What I have is mine and she can’t fuckin’ have it. She’s not going to be able to write lyrics like me, and even if she does get up onstage with a guitar, it's not going to last. I don’t care how vain and arrogant this sounds, but just watch: in her next video, Madonna is going to have roots. She’s going to have smeared eyeliner. And that’s me." Courtney pauses, pressing the dress against her body to check the size. "In some pictures, I come across as a fourteen-year-old battered rape victim," she continues. "And she wants that image." Madonna’s response to this outburst? "Who," she asks, "is Courtney Love?"

Nevertheless, Courtney is very serious about her vendettas. They have an equalizing effect: by trashing the likes of Madonna she becomes, in some twisted way, her peer. "Courtney’s delusional," says Bjelland, who hasn’t spoken to her in a year. "I called her a while ago because I was worried about her baby and her sanity, but I never heard back from her. In the past, I always forgave her, but I can’t anymore. Last night, I had a dream that I killed her. I was really happy."

None of this fazes Courtney...she isn’t particularly interested in the consequences of her actions. She is, instead, after a certain kind of acknowledgment. Courtney wants her power known, and aside from the fact that everyone is stealing from her, she feels one of her main obstacles in this quest is the whole beauty thing. She has written a fanzine for Hole devotees called And She’s Not Even Pretty because, she explains, "a lot of the anti-Courtney factions say, ‘And she’s not even pretty. Here’s this new rock star..Kurt..and he’s supposed to be married to a model and he’s married to me."

This delights her, and she takes her stack of dresses over to Kurt, who is still carefully looking at each pair of jeans. He seems in a trancelike state and the salespeople, who all recognize him, keep their distance. "Isn’t he pretty?" she says. Kurt doesn’t seem to hear her. "We go out once in a while and women look at him like they’re starving," she goes on. Kurt continues to move through the rack in slow motion. "A lot of people want a piece of that new fame thing," she says. "I can understand that."

It’s later the same evening and Kurt is sitting in the parking lot of a 7-Eleven, waiting for Courtney to buy dinner, which consists of cookies, fruit juice, and cigarettes. As he stares out the window, a large van pulls up and a guy in full heavy-metal gear gets out. He is wearing a Nirvana T-shirt.

"That guy has on a Nirvana T-shirt," Kurt says rather sadly. The heavy-metal audience was not what he had in mind when he wrote "Smells Like Teen Spirit." "I’m used to it now. I guess," he says softly. "I’ve seen it a lot."

Commercial success in the alternative world ruins your credibility and Kurt is deeply concerned with staying true to his vision. He wouldn’t perform at Axl Rose’s thirtieth-birthday bash (Rose is a big Nirvana fan) and turned down a spot on this summer’s Metallica/Guns N’ Roses tour. Still and all, "the general consensus is that Nirvana should quit," says Bjelland. "They’ve reached... nirvana. What are you going to do after that?"

This is ridiculous logic, but it is the conventional wisdom within the community. "Courtney," Kurt says when she returns, "that heavy-metal guy was wearing a Nirvana T-shirt." "I know," she says, munching on a cookie. "I saw him." There is a long pause while they ponder this reality.

"I’m neurotic about credibility." Courtney says finally. "And Kurt is neurotic about it, too. He’s dealing with people who like his band who he despises. For instance, a girl was raped in Reno. When they were raping her, they were singing ‘Polly,’ a Nirvana song." Courtney pauses. "These are the people who listen to him."

"But there are all kinds of fame," she continues. "Like the Replacements had Respect Fame. Big Respect Fame. And that kind of fame can really mess with your head. Rather than, say, Paula Abdul fame. That is Valley Fame."

Kurt laughs. Courtney has a basic, commonsense approach to business matters that clearly appeals to him. "Credibility is credibility," she says. "All these labels signing everything that moves because they think they can purchase credibility. They think they can market it. And I say, Let them try." Kurt turns the key in the ignition. "Why do I want what I want?" she says, although no one's asked the question. "You have to give yourself some bogus-sincere nineties little reason about what it is that’s making you go. And mine is influence." Kurt smiles. He knows what she’s talking about.

"Hi!"

It’s a month later and Kurt sounds like a new man. Cheerful! Alert! He’s talking on the phone from their hotel room in Seattle, where he and Courtney are rehearsing with their respective bands. "It’s great to play with the boys again," he says. He chatters on about his car (an old Plymouth Valiant) and the recent riots in L.A. "Courtney is out at the sauna," he says. "She’s really pregnant now, but she’s not that big. I think we’ll have a little elf baby."

Four hours later, Courtney is on the line. She, too, sounds happy and less manic. She’s full of news: there are rumblings that Gus Van Sant (Drugstore Cowboy, My Own Private Idaho) wants to put her in his next movie, she’s found a new bassist for Hole, and she and Kurt have bought a house in Seattle. "Nothing is better than being landed gentry," she says. "You must own property. That’s what I told Kurt."

Nirvana is going on a mini-tour in Scandinavia, and the baby is due in early September. "It’s the same day as the MTV Video Awards," Courtney says. "I think it’s very important that Kurt play that, but he doesn’t think like I do. If I was him, I’d have to play the video awards. I appreciate money. Kurt doesn’t see it the same way."

This is typical Courtney...eyes always on the prize. "I heard a couple of new rumors about me," she says gleefully. "That I’m Nike and Kurt married me for Nike money. That that’s why he’s attracted to me."

She laughs. There’s still talk about drugs and she knows it. Throughout the industry, there is increased worry about little Frances Bean. "The worst thing," she says, avoiding mention of the persistent drug rumors, "is when people say Kurt’s helping me to make it." She pauses. "If anything, Kurt has hurt me."

That’s going too far and Courtney stops herself. "No," she says, backpedaling. "Things are really good. It’s all coming true." Courtney laughs. "Although it could fuck up at any time. You never know."