RUDE AWAKENING -- A REVIEW OF "RAM DASS: FIERCE GRACE"

by Charles Carreon

March 14, 2006

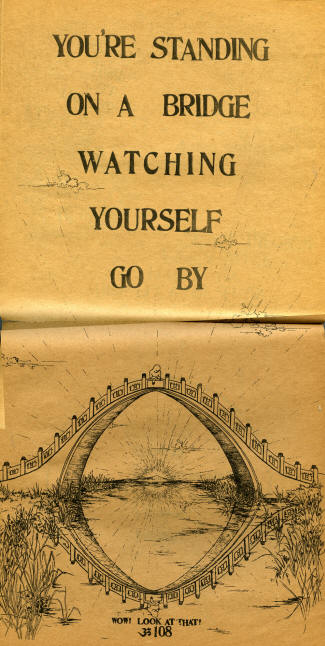

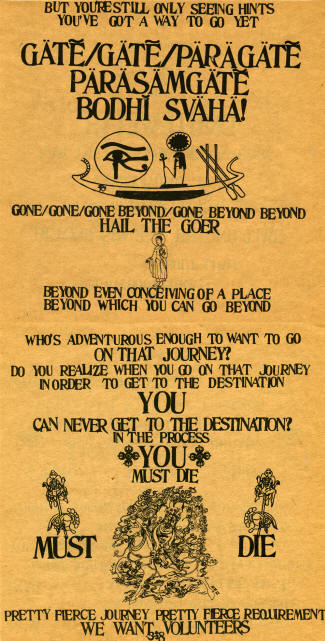

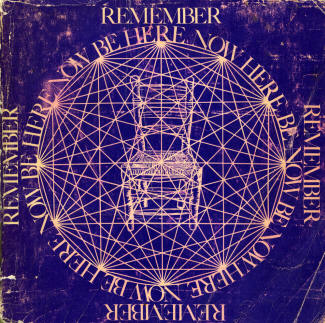

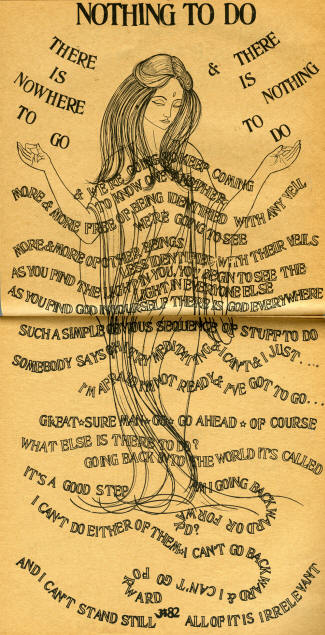

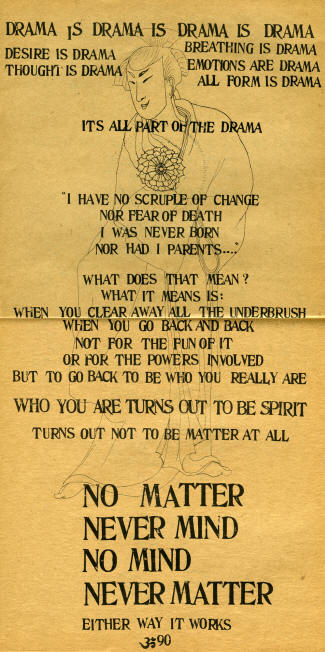

It was summer 1970 in Boston. I arrived at Logan airport, and had a layover in Boston for the night, so I stuck out my thumb outside the airport and quickly had a ride with a guy in a cool Porsche. I was fourteen years old, and I was sailing on the after-images of a day flying in a 727 on a hit of orange sunshine. The guy in the Porsche was really nice, had his professional trip and casual style. He said he’d take me to his place to crash and drive me back to the airport in the morning, but he needed to pick up a book downtown by this guy who had just given a talk in town. When we got back to his place, he said he had to crash because he’d been burning himself out. He gave me two hits of purple microdot, saying they weren’t really that strong, and left me to sit out the night. I dropped the two hits of purple microdot, which were tiny little pills, domed on each side, with a flat ridge around the edge, a dull purple color. They weren’t that strong, but they weren’t that weak, either. As the night wore on, sitting in the nice man’s living room, I had the company of the book he had just bought, that was also purple, and had a chair on the front of it, locked in a circle at the center of intersecting lines. Around the edge of the circle it said “BE HERE NOW.”

It was a long and beautiful night, a strange trip away from myself. I didn’t follow all of the logic and reasoning, not really, but the flow of images of saintly men and women, of dancing gods and goddesses, illustrating the world as a vast golden loop of infinity, drew me in like a net of seduction. By morning, when my very gracious host rose to ferry me back to the airport as promised, I had one more favor to ask of him – could I please buy this book from him? I still have the book, and it bears on the inside front cover a wacky fourteen-year-old-on-acid attempt to claim ownership of the book on behalf of a non-self. It’s hilarious, and warming to remember when I wrote those words, sailing aloft on wings of steel, peering out at the earth below, glorying in my mind and in the fact that I had found friends. For years I had been navigating the byways of psychedelic space with no vocabulary or context to guide my explorations. My prep school pals and I had no tools for confronting the inner landscape that yawned open before our youthful eyes. Seeing is believing, and we had seen a world we had never suspected existed within us. Now this guy, Ram Dass, Tim Leary’s pal that also got kicked out of Harvard, was teaching this Indian guru path and making it look cool.

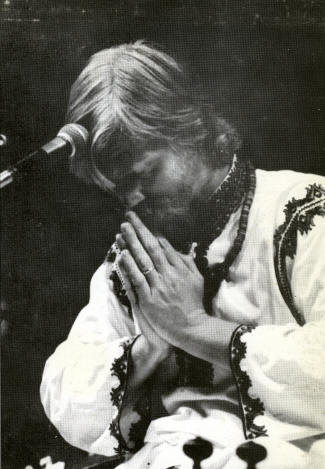

Three years later I was seventeen, living in Tempe, Arizona, going to school, wearing sandals, flowered shirts and cutoffs, and I had a friend named Jane who was a waitress at Earthen Joy, the extremely wonderful natural food restaurant next door to Gentle Strength Coop and across the street from Changing Hands Books and the Buffalo Exchange. One day I met Jane on the ASU campus and she told me she was going to see this cool guy speak, so I went with Jane. It was Ram Dass, the guy who wrote the purple book, that frankly I hadn’t thought about in quite some time. It must’ve been hosted by the Yogi Bhajan crew, because they had the front-circle position, and seemed to know what they were doing. I was a young kid far more interested in girls than God, and yet, there was something about his voice that I really liked. After an hour or so, Ram Dass said it was time for some of us to go, and that’s when Jane and I parted company, she staying, me going.

Of Death & Compassion

I went off into the Arizona night, bicycling on the broad concrete arteries of the ASU campus, off into my life. I met a beautiful, slender blonde girl during the spring semester, and in one of those silly rebound things, I swapped my lukewarm relationship with a Catholic girl who acted Jewish for a wild head-over-heels obsession with the blonde. That summer we took a hitchhiking trip from Denver to Dallas to Florida, back up into Tennessee and Kentucky, north to Michigan and then back to Phoenix. We could cover some territory in those days. My girl had a yard of flashing gold streaming from her head, legs like a gazelle and a toothy smile. We made good time, but in the American South, that just means you hit trouble faster.

One night in Kentucky, we found ourselves on the wrong side of Green River, having a verbal dispute in a car with a man who was drunk, very big and strong. My girl said she had bad vibes from the guy when the car lurched to a stop next to us as we walked down the road. Our suspicions grew when he drove the car onto a one-car ferry that, he advised us, stopped running at nine, and took us to the other shore. As we drove on, the place he said he was taking us was just always a little farther, a little farther into the darkening Kentucky hills until the sunset turned to dusk turned to dark and at last in the pitch black night he declared that we were at the place, out in the middle of nowhere, and just needed to walk down to a lake. Nope, nope, nope. That wasn’t something my girl was going to do. And besides, she said, we had to trade places, because he’d been squeezing her leg during the whole ride. He was mad when we decided not to walk down to the “lake,” madder still when I insisted on sitting between him and my girl, and really mad after he pulled off the main road and I said “Whoa, whoa, whoa, where are we going?” He said he was taking a shortcut. I told him he was scaring us. He told me he got scared sometimes, too, which is why he kept a 357 under the seat.

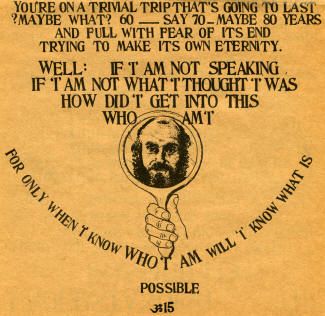

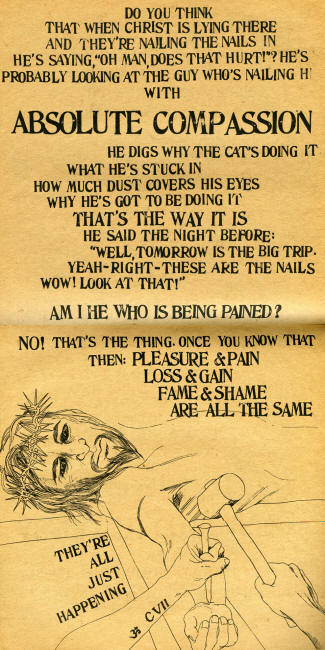

Quick thinking was required, but what I remembered was that guy in Tempe, in the robe with the beads and the beard. I remembered the page in the Be Here Now book where Ram Dass is looking at his own image in the mirror. It suddenly occurred to me that the man behind the wheel, basically announcing that he was going to kill us, was a very unhappy man. It occurred to me that Ram Dass might say we should feel compassion toward this person. I remembered the page of Be Here Now where Ram Dass wrote that as his torturers were nailing him to the cross, Christ was probably feeling sorry for them. The driver got back on the main road, to my relief. Suddenly it occurred to me that I was not drinking or smoking, but the man was. I realized I must appear to be a strange person, a skinny guy with long, curly hair who doesn’t smoke or drink. I had quit smoking years before, and didn’t like beer much at all, but I asked the man if I could have a beer and a cigarette. He said yes, of course. I lit up and popped the beer can and drank and smoked, genuinely thankful to our host, who suddenly began expressing the earnest hope that we would not miss the last ferry and get stuck in the dark on the wrong side of Green River. He was driving about as fast as you should on the two-lane road, and when we saw that the last ferry was still there, we were all joyful. As we reached the other shore, the man apologized for the events of the night, explaining that sometimes he went kind of crazy. He would like to make it up to us, he said, but we were out of the car, hauling our huge backpacks as fast as we could, and literally tearing through the woods away from the terror car at top speed to get away.

Go East, Young Seekers

My girlfriend and I didn’t actually change our hitchhiking habits, just our choice of rides, but the fact was, life in other people’s cars was hazardous. We married young and traveled around the country. We got our own cars, but they were miserable experiences, always breaking down, costing too much, sending you back to the grinding system of cash generation with its boring, downer bosses, tedious material trips, and of course, restaurant jobs. Reading gets you out of your space, though, and I read anything I could find on yoga. Autobiography of A Yogi was everywhere, being pushed through the food coops and head shops where you found eastern spiritual literature in those days, and I was seized by the miracles of consciousness laid out in the book. Paramahansa Yogananda’s story was romantically beautiful. All of the problems of life were intended to be resolved through inner peace. Nothing seemed more likely to me. I had been on this subjective approach to reality for a long time.

So had Richard Alpert, the Harvard professor who would become Ram Dass. Until adulthood he enjoyed being a rich man’s son, intelligent and handsome, a doctor, a professor with money and friends. He was a tenured professor at Harvard before age forty, and the world, as he put it himself, “was his oyster.” Indeed it was. Psychedelic experiences, however, upped the ante. No longer good enough to be rich, good looking, admired and respected. Now he needed to discover the who-less who of himself, that he had become so acquainted with while flossing his brain cells with Doctor Hoffman’s mold extract. For that, only a trip to India, toting along a little medicine kit stuffed with White Lightning, 305 micrograms per little white pill, would suffice. And yes, at the top of a high mountain. Yes, at an old temple! Yes, a funny old man! Who can take all the White Lightning in the bottle, enough to make your face melt off and run down into your bellybutton, and just tease you about it. Yes, it’s God – the acid-free acid-head! LSD was the fulcrum of Richard Alpert’s psyche, the philosopher’s stone of consciousness, and like a redneck who will respect anyone who can hold his liquor, Alpert had to bow down to someone for whom acid was nothing. Not much of a well-reasoned philosophy there, but it has a certain je ne se quois.

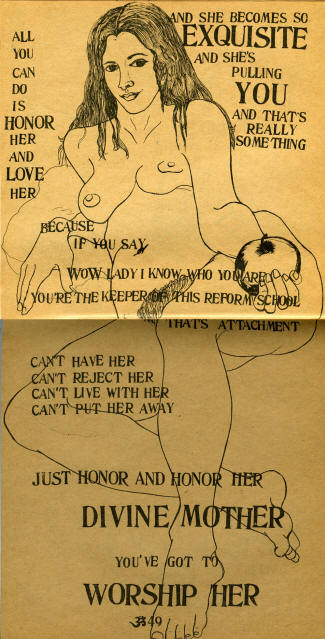

Having gotten out of Boston and into the invigorating air of the Indian highlands, Richard Alpert found a new source of authority to make up for his loss of his teaching position in academe, the mysterious little-known holy man, Neem Karoli Baba. Neems are a type of Indian pine tree, so you can deduce that this Baba lived way out in nowhere, where nobody ever went to see him. The perfect guru for a man starting over. And indeed, according to Ram Dass, the only recorder of the events he described, they hit it off famously. Neem Karoli Baba once even told an old disciple who wanted to touch his feet to go touch Ram Dass’s instead. When the guy gave Ram Dass the devotional foot-touch, Neem Karoli Baba smiled at him. You can take the meaning any way you want. Ram Dass certainly did. The newly-named Ram Dass went to work on his image with a lack of subtlety that would have caused comment if anyone had understood what he was doing. We were so relieved to get someone who could talk about Indian philosophy without an accent, who could wear a robe but not be a priest, who had a beard like Freud, and joked about being Jewish and getting bloated after eating ice cream, that we just didn’t criticize. When he said we had to read the Bhagavad Gita, and we became the Arjunas of our personal Mahabharata epics, we knew we had Ram Dass to thank for entry into the mysterious East. No silly turbans like stage clairvoyants. No table-tapping and parlor stunts like spiritualists. Just good old fashioned internal holographic displays like you saw on acid, that had to be real. Meditation isn’t that hard, man. You’ll be tripping out in no time – Ram Dass is already on a much higher plane than the rest of us. His guru told him to feed people. His guru could read his thoughts. His guru was already so high that acid did nothing to him. Really! Talk about mind over matter. That was proof that the West had nothing on the East. They would just meditate those mushroom clouds into lotus blossoms.

So I and my girlfriend, like lots of other people, followed Ram Dass’s example and traveled all the way to India. We hitchhiked from Eugene to Phoenix to New York, caught the Icelandic cheap fare to Luxembourg, Belgium, hitchhiked to Munich, caught the train to Istanbul, and took buses through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Jammu and Kashmir, before we arrived at the Sacred Ganges river. There we sought out the grandson of Yogananda’s guru. We found him without much trouble. His address was as listed in the Spiritual Community Guide, but he wasn’t, as the Guide claimed, “giving strong Kriya Yoga teachings.” He wouldn’t teach us at all, he said, because a Guru took on a big job, a lifetime job, with each disciple, and he couldn’t do it if we lived in America. He had only one English-speaking student, and he spoke Hindi and had read the Upanishads in the original language before they ever met. He was sorry, and unmoved. We would have to get the yoga lessons through the mail that Yogananda’s group offered. That was for us.

So the Hindus had no use for us, and generally didn’t allow non-Hindus into their temples. While Ram Dass had led us all to believe that spiritual bonhomie was the general rule in India, we found this to be untrue. The Indians had little use for foreigners entirely, unless they could sell us something, haggling with earnest sincerity. As poor as we were, we took classes in tabla and bonsuri from three men who were all from the same Brahmin family, and through this contact gained some familiarity with the attitude of ceremony and gentle arrogance typical of the Indian upper class. We wondered without understanding as we saw people thronging the streets of Benares, carbuncled with temples great and small, overgrown with banyans, populated by orange-robed sannyasis, moving along the shores of the great Ganges river, lined with burning ghats and temples, edge to edge for miles and miles.

We studied some Buddhist meditation with an English monk named Luong-Pi, who taught mindfulness meditation. I couldn’t abide the stuffy stillness of the Buddhist approach, the tedious attention to little sensations. I enjoyed the colorful style of the Hindus, the gods and goddesses, the stories, the tales of how one deity created illusions that other deities would purify and redeem. India was a great vacation from the Western mindset, as Ram Dass had promised. We came back more alienated from our homeland than before. The remedy for this feeling was total immersion in spirituality.

Neo-Tibetans Take To The Woods

In 1978, my wife and I became the disciples of a bonafide Tibetan Rinpoche, and we built a house in the woods with help from several friends who knew nothing about carpentry, and lived there for three years on next to nothing, exploring the life of the spirit and the emptiness of the natural world. I dedicated myself to the life of the spirit, trusting that the material world would take care of itself, and in 1982 that had all lined up. I was living with my wife and two kids in a yurt out in an Oregon meadow. We were homesteading as Buddhist pilgrims in a field of alfalfa gone to seed and teasle making a comeback. We lived on student aid, food stamps, and what I could make cutting wood at about $2.80 an hour, not figuring the cost of saw-sharpening and other necessary expenses.

Poverty – not having the money to buy anything you wanted, and only some of what you needed – was our difficult friend. It kept us simple, but it kept us weak. We had very little power or independence. Like poor people all over the world, we kept as still as circumstances permitted, to keep our expenses as low as possible. We knew how long the honey, the peanut butter, and the whole wheat flour were likely to last, and when we’d get food stamps next. I just read last night in “The Intelligent Investor” by investing guru Benjamin Graham that from 1972, when I got out of high school, until 1983, when I left Oregon to get a law degree in LA, the cost of living doubled — the largest ten-year rise in US history. So times really were tough, and we bore them pretty stoically, raising a couple of little kids in a little house in a meadow, just like the Waltons, the TV family in “Little House on The Prairie,” a popular show of which I never saw a full episode. Ironically, it made us feel cutting-edge to be out of touch, because we were living the reality other Americans were watching, since like the Waltons, we had no electricity and no reception, and thus also like the Waltons, we weren't distracted from the beauty of the natural world by television. We maybe went to the movies twice a year, and ate out only under the direst circumstances of necessity. Our main source of entertainment consisted in feasting on scenery and silence, studying the shade of the sky, listening to the birds and crickets, and hating the deer for eating our garden. These were all healthy pursuits that cost nothing, except the loss of the garden to the deer, hence the anger. Everyday living left us with nothing extra to put towards pleasure travel.

So when we heard that our guru was giving a talk along with Ram Dass up in Eugene, it was a conundrum. The drive was four hours, and we didn’t want to risk the trip if it would cause us to suffer a car breakdown. We could not abide the thought that our car might break down. It was our lifeline to town. Everything depended on it. It was local hippie lore that the drive to Eugene, over all the insane passes north of Grants Pass, Rice Hill, etcetera, had put an end to more than one good workaday vehicle. We didn’t know what to do, because we really wanted to go. I had never thrown the I Ching before, but the matter seemed to demand some third-party input. I tried to figure out the method of casting the lines, and in fact got it backward, but derived a hexagram that said, in the John Blofeld version: “The superior man does nothing that is trivial.” The changing line added the commentary that “There is great power in the cart axle.” The heavens had spoken. The matter was settled. We roasted a chicken, made potato salad, packed the car and made the trip to Eugene. Of course everyone went up to see Ram Dass, and no one paid a lick of attention to my guru, who was an unromantic Tibetan man with bucked teeth and a wicked sense of humor that, however, you had to take the time to appreciate. I remember Ram Dass’s words to me as our eyes met briefly when I went up to see him. He gave me a friendly guy-to-guy word of encouragement – “We’ve been doing this for a long time, haven’t we?” It felt great, like a shot of encouragement right in my heart. We’d been doing it a long time, together, me and Ram Dass and all the other folks on the liberation train. All of us.

Secret Teachings

A month or so later, I was talking with my buck-toothed guru on a hill where there’s now a big temple. At that time, all we had were underfunded projects, so we built things out of logs and poles, and on that day we’d been working on a deck where some teachings were going to take place that summer. My guru said to me that Ram Dass, or “that guy,” as he called him, had taught him a lot. He said yes, that he had spent three days reading over his texts, preparing with his translator to deliver the teaching he gave in Eugene, but that Ram Dass had just sat there on a chair with his legs folded under him, smiling like he was having the greatest time, and talking about just anything. The Buddhist Dharma, he said to me, was not very sexy. It was, he said, like a big, ugly old truck with a noisy engine and a cab that fills up with dust and exhaust. Still, all the great masters of the past, Guru Rinpoche, Milarepa, Naropa, all of them, traveled in that same, ugly old truck, so we must use it. Ram Dass, he said, offered a much more flexible, stylish alternative. He recognized that, and was amazed at how Ram Dass had derived spiritual lessons from everything. His teachings, my guru said, were like the CIA – they might be hiding anywhere, behind any rock or tree. As he said this, he jumped around, looking behind this tree and that rock until I grasped his wacky analogy and laughed. I was in total agreement with his confessional about the geeky appearance of our Dharma vehicle, but also, I heard the ring of noble adherence to tradition in his voice, and was attracted by it. The Dharma truck, yes, I would ride in the Dharma truck.

Around that same time, I encountered Bhagavan Dass, the surfer-dude-cum-yogi who introduced Ram Dass to Neem Karoli Baba, in the kitchen of our Ashland Buddhist center on 2nd Street, in a location that has been turned into a garden restaurant because of its sunny exposure in an above-the-boulevard location. It was a sunny day when I met Bhagavan Dass, and while I was thrilled, he seemed to be a totally regular guy, not a spiritual leader in any sense. You could say he was unassuming, perhaps. What seemed strange was that in Be Here Now, Ram Dass had described Bhagavan Dass as a stellar spiritual exemplar, a man who was literally always in the flow and in the know. Perhaps, I figured, he needed the hash he was smoking in India to keep his Shiva-baba mojo going, and just slid down the psychic totem pole without it. I assumed Ram Dass had told Bhagavan Dass to check out Oregon, because his joint appearance in Eugene with Gyatrul Rinpoche had a huge turnout of over three-thousand people. Of course, he might have been headed for Antelope, Oregon, the town that the Osho/Rajneesh cult took over and turned into the last known preserve where antique Rolls Royce automobiles could roam freely in the open fields. Certainly such an environment would have been more congruent with Bhagavan Dass's interests, that struck me as regrettably concrete. I would have liked to ask him the whereabouts of Neem Karoli Baba, or his reminiscences of sojourns in the upper Ganges regions where sadhus have lived and grooved the life ecstatic for millennia. But he was focused on prospects for immediate financial improvement, and just asked about money-making opportunities in the astrological field, his wife's specialty, to which I replied that in Ashland we were historically overstaffed in that department. He and Mrs. Bhagavan Dass left town the same day they arrived, as I recall.

I wasn't critical of Bhagavan Dass being focused on his own welfare rather than ministering to the flock like his friend Ram Dass — after all, everyone has to pay for their brown rice and tofu, and indeed my own attention was increasingly focused on material matters. Certainly the idea of me meditating had turned into a huge joke with Gyatrul Rinpoche — once when I asked him what the secret mandala offering was, he responded that it was the Chod practice of exorcism, but that the real secret was how I'd been supposedly doing my preliminary hundred-thousand mantras and mandala offerings for years now, and still hadn't completed anything. About that time he also started calling me “Grandma Lawyer,” apparently because I was as loquacious as an old Tibetan woman. By alluding to my future career choice, my guru was gently showing me the door to the yurt. It was time to venture out of the vajra circle and attend to concrete reality.

I began to recognize that poverty was an obstacle to fulfilling my life desires. Further, it became a source of humiliation after wo students bought the land we were living on in a homemade yurt, and gave it to Gyatrul Rinpoche. Now we lived on the Buddha's land, and officious Dharma jerks would come by and critique the layout of our yurt, the location of the outhouse, and the fact that our refrigerator was under the porch. I wanted to buy land, and be close to my guru, but I was so broke that owning land was a ridiculous pipe dream, and my guru obviously took affluent people more seriously and regretted that so many of the Dharma simpletons drawn to esoteric Buddhism literally lacked even pots in which to piss. We were so obviously penniless that no real estate agent would have even wasted time talking to us. Reagan had become president, and was “staying the course” through the worst of the post-cold war recession, and it seemed harder times lay ahead. My mom had died unexpectedly, my father was sunk in grief, and the world without mom was mighty unfriendly — she had always helped us financially in little ways, and her death left us literally poorer than ever. In the summer of 1982, after my mom died, Gyatrul Rinpoche started work on the monumental 32-foot high statue of Vajrasattva Buddha, and told me to work only on that project, to dedicate all the merit to my mother as the representative of all sentient beings, and not to worry no matter how poor I got. I got so poor I couldn’t buy shoes. I wrote a poem about it, but it didn’t make me feel much better. I really had no shoes. My wife and I had created a third child, a lovely little girl, and I started to feel motivated toward material independence like never before in my life. Three months of continuous hard physical labor for ten to twelve hours a day, working on the foundation of the statue, had a healing effect on my grief-stricken mind, no doubt. When the academic year began, I returned to college, finished my last year of undergraduate work, took the LSAT, and got ready to join the rat race I had avoided for a decade.

Professional Buddhists

With Gyatrul Rinpoche’s strong encouragement, I went to law school at UCLA. We moved to LA with three kids and Tara at the wheel of a white and blue 61 Econoline church window-van, and me pulling a U-Haul with no blinkers behind a slant six Dodge half-ton pickup piled high with domestic belongings and crowned with Tara's rocking chair. We looked painfully like the Beverly Hillbillies, and were literally jeered by a drunk guy in a satin jacket crossing the street and eating a slice of pizza — we startled him so badly with our parade that he almost lost his cheese. Somewhere in the back of the pickup was a Vespa scooter I got from Mitchell Frangadakis in exchange for a kickass little gas-powered portable water pump that had been our running water source in the yurt that we had lived in for three years and was now lying disassembled inside an old barn in Colestine Valley. I sold the Vespa to a black mod kid who would have pushed his grandma off a cliff to get it, and a few months later he showed me the brutal gash on his shin where he'd piled it into an open car door while lane-splitting. I sold the truck a year later to an appreciative surfer dude from Tujunga for $425. But the van I would not let go of. I drove out of Topanga one day with my hand reaching into the engine compartment, grabbing the carburetor throttle with my bare hands, a drive of about ten miles through stop and go traffic on PCH. It was a goner, though, after some jerk yelled at Tara in Century City as she toodled down Avenue of the Stars, “Get that junker off the road!” We swapped it for a Mercedes 240D my dad spotted as a bargain in Phoenix, that served until I burned it up three years later and traded up to a Cherokee in preparation for our return to Oregon. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

My wife got straight clothes, put on a little makeup, got a job with no experience from a guy with no class by agreeing to work two weeks for free. She worked as a top-flight legal secretary for the next twenty years. I got a haircut, a California bar license, large debts, and the means to earn money to buy land. I worked in a skyscraper in a big city, about twelve hours a day, and in the evenings we hosted Dharma events at our house, which was one of the main Tibetan Buddhist centers in a large metropolis. Life was simple, and we kept it that way. With the guru at the top, everything else fell into line. Sometimes when he came to the big city, he stayed at our house.

My guru was almost always very pleasant with me, and had a generally good feeling about my spiritual potential. He had spotted me hundreds of thousands of mantras so I could take teachings I wasn’t qualified to receive, but he figured I’d need a lot of retreat time to grind off the worldly professional patina I was acquiring in my big city job, and paying for the standard three-year retreat was another conundrum. The years went by, and I remained stuck in the big city, and when I came back to visit him, he would always ask if I was making progress toward moving back. I often told him I needed to get out of debt to move back near him, and once, after I’d been gone nearly ten years, he asked, “Are you getting out of debt?” We were, but so slowly, at times it was imperceptible. Eventually, debt or no debt, we had to get out of the metropolis. The Rodney King uprising blighted the energy of the city severely, and so in 1993, ten years after we exchanged hippiedom for yuppitude, we reversed course and headed back to the woods to reclaim our spiritual roots.

Back To The Compound

We built another yurt on a parcel of twenty acres overlooking the impressive three-story temple my guru had built with Chinese dollars and American sweat. My life seemed stable, and although the isolated country setting was inconvenient for my kids’ social lives, everyone had to sacrifice so we could be close to the Dharma. As luck would have it, the whole thing was not a happy homecoming. There was a terrible anticlimax about the whole situation. We had moved to the big city, lived there for ten years, bought land and moved back to the country to be near our guru, and built a house from the driveway of which we could see the golden roof of his house every morning. What was wrong? Well, by the time we got there, the guru was effectively gone. He had experienced a marital upset – his wife running off with a young Tibetan monk to whom my guru had shown great generosity. But there you have it – no good deed will go unpunished.

I and all of the other students had thought my guru and his wife were the Divine Couple, and as their relationship unraveled, various students were drawn into intrigues, enlisted as allies by the wife and guru respectively, and in several cases, watched as their faith was sacrificed to the newly-pragmatic order of the day. Strange new faces showed up around the temple – a Hollywood martial arts actor newly-recognized as a reincarnated tulku and his entourage. It was enough to give the most hardened stomach vertigo. The guru spent time huddled with top disciples, planning countermoves, and students stayed away in droves. A sorrow that would not disperse pervaded the place.

My guru seemed to lose all pleasure in being at his temple, a place that had been built so tantric practitioners could perform Dzogchen, Mahamudra, Trek Chod and Togyal meditations, and realize the rainbow body. The place was lonely as hell. The mountain beauty surrounding the temple became desolate and sad. The hearts of the students were dazed, confused, and silently aching. Nothing made sense. The looming temple, the monumental statues, the rows of gleaming water bowls, the multicolored brocades, the bundles of incense, the flickering butter lamps, all their colors faded when deprived of the presence of the guru whose inspiration had brought it all together, then abandoned his creation.

My guru ultimately moved away to a windy hilltop near the sea, a few hundred miles from the temple. The house was provided for his use by a wealthy young woman who had appeared about a year before at the temple. They moved into a big house on a hilltop hear the Pacific, and the coterie of devotees who must be close to the guru, and have no children or other ties to bind them, moved down there and assembled a new court.

So after ten years in the big city and moving back to the country to connect with my spiritual circle, after a couple of years back in the compound, the whole arrangement unraveled like an old sweater when somebody pulls the wrong thread. An empty temple is a lonely place that engenders a lot of strange game-playing among the students. Once in Benares we walked through a temple where a single lonely sadhu was dolefully playing a drum and singing. The local fellow who was showing us the way to our destination told us it was a temple where the guru had died. Well, that had struck me as a problem with gurus – succession planning might be difficult – but I didn’t do anything to deal with it. When the time came, and my guru effectively abdicated his throne to deal with a case of personal depression, it left me, and more importantly, the devoted members of my family, bereft of direction.