Wipeout

For my wife, losing faith was about as painful as losing her skin. For over twenty years she had invested every waking thought in the project of self-perfection according to the Tibetan Buddhist philosophy. She had performed a hundred thousand prostrations, many more than a million mantras, transcribed and edited teachings by our guru, built thrones, sewed every ecclesiastical fabric creation requested of her, and managed hundreds of meals and ceremonies, large and small. When she realized that nothing good had happened to her mind as a result of all her efforts, and that she was just as far from clear on the meaning of Buddhism as she had been years before, she was enraged. As the thought-structure she had created began to come apart, it was about as dramatic as the Challenger explosion, and for several years she was condemned to repeat it daily. Self-deprogramming from a delusive worldview can be painful.

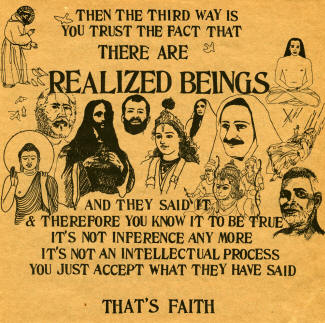

My faith in Buddhism had always been tenuous, but losing it altogether was no fun. By tenuous, I mean that I always felt like a phony practitioner. My mind is incorrigibly active, and meditating had always made me more uptight, to be honest. I certainly didn’t get the hang of trancing out in meditation, like Ram Dass, who found it an adequate substitute for drugs. I generally considered myself more lucky than good, but luck is all about associating with the lucky. The lucky ones in my pantheon were the Siddhas and Mad Saints who overleaped the restraints of this world to declare the triumph of the human spirit. I had gotten quite used to relying upon their company to enliven the dreary confines of the workaday world. I was also very used to the company of wrathful and peaceful deities whose presence I had cultivated. My Buddhist lifestyle had made me able to balance various different personalities on the theory that my inherent nature was empty, but in actual fact, I had gone somewhat crazy. I woke up to my condition one day after reading a book by a Miriam Williams who had spent fifteen years of her life in the Children of God Christian sex cult, a cult that I myself had been in just before it went altogether freaky. I realized I’d been in one cult, then gotten into another one, and spent twenty years in it. My self-delusion that I hadn’t been in a cult crumbled as I reviewed the last years of my life, how I had ended up living in a remote backwoods location near an empty temple where an old Tibetan lama had broken up with his wife, and nothing very interesting was happening at all.

When we lose faith, we lose several sources of psychological comfort. We lose the social agreement and ritual activities we shared with other believers. We will no longer share homilies with the Sangha. We will not regularly read Dharma books with a reverent air. We will not push ourselves on toward the goal of enlightenment for the sake of all beings with that terribly earnest style. We will not wear special clothes, sport prayer paraphernalia or religious fashion accents. The evenings become strangely lonely when you have no fellow-believers to shore up your self-image.

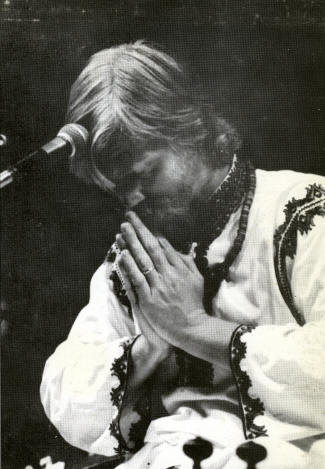

I have recounted how my experiences first led me to embrace, then reject, spiritual doctrines of the sort endorsed by Ram Dass, because few people experience religious disillusionment after a long period of belief, and apostates are often not very outspoken about their despair. The faithful certainly don’t want to hear about it. Therefore, it is significant that Ram Dass clearly states in Fierce Grace that after a lifetime of faith, his near-death experience devastated his beliefs, leaving him far less certain of his beliefs than he appeared during his long and apparently self-deluded career as a spiritual teacher.

Ram Dass’s Excessively Real Visualization

During the last quarter of the twentieth century, Ram Dass was iconified as the epitome of a New Age guru with unquestioned credentials. His achievements were logged in the hall of fame and required no further confirmation. As he passed into middle age, he kept cranking out lectures that were turned into books, and kept certifying the experiences and writings of other spiritual lights. Like a restless explorer always looking for new places to discover, he at last settled into “aging” as his next big frontier. Of course, he subjected his encroaching decrepitude to the same internal scrutiny he had perfected with his meditator’s eye. One day he was visualizing what it would be like to have failing eyesight and other weakened faculties, when it stopped being an experiment, a speculation. Most human potential fans say that if you visualize something really clearly, it becomes reality, and Ram Dass should’ve probably taken that promise more seriously.

Ram Dass had just answered the phone when he began exhibiting severe symptoms caused by a cerebral hemorrhage from a ruptured blood vessel in his brain. A cerebral hemorrhage leads to unconsciousness, coma, brain damage and death as blood pressure increases inside the braincase. Ram Dass had begun to slur his words, and his friend on the other end of the line, concerned, called the paramedics. “When I answered the phone, my right side wasn't working, my words were slurred, and the friend on the phone was worried,“ Ram Dass said about the stroke. ”My friends called 911. I was on the floor when these big young firemen came. They stared at me and suddenly, I knew what it was to be old. On the gurney I remember the pipes and the long faces of the doctors and nurses. Later, I found out they thought I was dying.” An attending physician said, “Ram Dass had a massive left hemorrhagic stroke and I believe he had chronic hypertension. Since I am not his personal physician, I cannot tell you how closely his blood pressure was followed nor if it was controlled, so that may have played a part in his stroke.” The lay name for hypertension is high blood pressure. When the blood pressure went up too high inside Ram Dass’s blood vessels, one of them ruptured in his brain, and then the pressure started going up inside his braincase, and then he started dying.

Ironically, most doctors today will tell you “yoga” is good for reducing your blood pressure. The doctors of course are thinking of hatha yoga asanas and pranayama, the rhythmic stretching, relaxing and breathing exercises that some yoga practicioners perform. Apparently Ram Dass was dedicated to a subtler “heart yoga,” which he sometimes taught people to practice by imagining that they had nostrils in the middle of their chest. It must have worked for him, but he apparently missed the fact that he wasn’t taking care of his body. Like many spiritual athletes filled to the brim with the adulation of disciples, his specialness had inflated to such a dimension that it blocked an honest view of himself. In the midst of the last thirty years of hoopla, it had slipped his mind that, when it comes to death, one size fits all.

Some of us don’t look forward to dying, but Ram Dass had been anticipating the moment when death would remove the fleshly barrier between himself and “Rama” the big blue God-king from ancient India whose name he had by now repeated millions of times. Constant recitation of Rama’s name was said to be like “placing a lamp at the door of the mouth, so there will be light within and without.” Pronounced with the last “a” silent, as in “Rahm,” Ghandi shouted out the holy name the moment his assassins cut him down. Ram Dass was fond of this story, of course.

But to his own great disappointment, during the moments when his brain was failing and he was plummeting toward death, Ram Dass didn’t remember Rama, God, guru, enlightenment, or anything spiritual at all. Of course, you can hardly blame him, since nothing happened to remind him of his planned after-death scenario. He didn’t travel through a long tunnel, he wasn’t drawn to a beautiful light, no guides showed up to meet him, and he didn’t return to this world because he still had work to do among the living. He just stared at the pipes on the ceiling, noticing that they were there. He didn’t think about God, not one little bit. There’s no mystery here, unless you want to invent one. Ram Dass’s malfunctioning brain couldn’t access the programs he’d stored to know when he was dying, and how to act. He’d locked his spiritual keys in his material vehicle, and wasn’t going anywhere.

Ironies abound in Ram Dass’s situation. Ram Dass apparently thought the power of the spirit could trump physical limitations, but his physical collapse has underlined the folly of ignoring one’s physical health if one wishes to enjoy continued mental clarity. He didn’t even know he had high blood pressure, or must’ve figured he’d just muddle through on good vibes. High blood pressure kills, and you don’t argue with the numbers – you get your blood pressure down or you die.

Ram Dass believed, however, that spirit and body were fundamentally distinct, and that he had set things up in such a way that his consciousness would trend upward into clarity and peace, gradually freed from earthly constraints into “liberation.” That is the fairy tale. Now, paralyzed and cognitively impaired, unable to drive his new car, to roll his own wheelchair, to speak clearly or express his intentions unambiguously, he is a living demonstration of how the mind depends on the body to experience suppleness and beauty.

The entire wisdom of Ram Dass’s teaching is of course called into question by his own sense of complete befuddlement when faced with precisely the event for which he’d been preparing for the last thirty years. Ram Dass’s philosophy flowed from his first psychedelic experience, when he believed he suffered “ego death,” and discovered that even though “nobody was home,” his existence-less self was still “minding the store.” After getting over the shocking effects of ego-death, Richard Alpert decided it was a good thing to go through, and that it should, logically, turn you into a holy man, which is why he became Ram Dass by means of the available route – going to India with a stash of psychedelics and looking for God among the hash-smokers of Benares. But whatever Richard Alpert’s ego-death was, it must have been really different from Ram Dass’s near-death experience, because he clearly did not conceive of it as a good thing, and it didn’t turn him into a holy man. It turned him into a very sad man.

Ram Dass placed his faith in the power of the spirit to soften the reality of life. By dint of good fortune and a kindly disposition, he did in fact make his life pleasant, and he articulated a cozy philosophy that has no doubt comforted legions of believers. The history of his popularity and the adulation he received are in the record books. But when death came it didn’t stop to look at the clippings and the videos and the audiotapes. It came straight for him, and he was unable to take proactive, conscious steps to manage the death experience. In the Mission Impossible moment when the smart yogi hot-wires reality and flies off with the dakini in a magic vehicle, he froze. Nothing looked right, and he forgot what to do. Whoa! Had he been studying the wrong map? Was he like an old convict who had always said he would escape, but dozed through the big jailbreak, and woke up inside the same old slammer? Or was the whole escape story just bullshit? Was there no “outside?” Perhaps what we see is all there is. Certainly Ram Dass couldn’t testify to anything different based on direct experience. He fell from a height of certainty into a chasm of doubt about our mortal destiny. Based on his own spiritual criteria, Ram Dass announced at the beginning of the film: “I failed the test. I have a lot of work to do.” Ram Dass never recants this dark declaration, and all by itself, this statement undermines a lifetime of confident pronouncements, as both his theory and practice appear to have left him a goodly distance short of the finish line.

Revisiting The Legacy

Fierce Grace doesn’t retell a fraction of Ram Dass’s career as a guru, and indeed, doesn’t pretend to be an entire biography. Nevertheless, to leave out the scope of his life activity presents a one-sided view of the man. His involvement in pyramid schemes like The Circle of Gold in the late seventies, which siphoned money into the hands of a few spiritual and political elitists based on a ridiculous metaphysical proposition that a pyramid scheme was just a brilliant method of investing money that would make the whole world rich if we’d just let it do its work. I remember two local healers brought two of the official Circle of Gold chain letters up from the Bay Area, that you had to buy for $150, and conveyed the right to sell them to two people for the equal price. A big selling point was that Ram Dass and other spiritual luminaries appeared as senders of the original letter. The healers were unable to sell the letters to the unventuresome Ashland hippies, who wanted to buy large bags of granola and dried fruit, not silly letters that anyone could write. A few months later the whole scheme went bust. Quite a saintly venture, that.

Left out entirely is the saucy story of Ram Dass’s humiliation at the hands of Chogyam Trungpa during the early years at Naropa Institute, when Trungpa, a throwback feudal lordling with eleven incarnations in the Tibetan Ancien Regime, showed him how a tulku wields spiritual power. Ram Dass felt unable to compete when Trungpa talked about lineage. He hadn’t even asked Neem Karoli Baba what his lineage was. In a painful humiliation that ran the spiritual circuit worldwide like a satellite transmission, Ram Dass’s friend, the Hindu troubadour, had his ass-length sadhu braid cut off by Trungpa as he lay unconscious after a night of drinking at Naropa. Trungpa explained that the braid was for sannyasis, not drunkards. After that major tonsorial event, Bhagavan Dass acquired a permanent shit-eating grin that he still displays in the movie, and although the braids are back and look okay, his eyebrows are ridiculous.

Fierce Grace also completely misses the Joya Santanya scandal. Ram Dass indiscriminately legitimized a lot of mediums and holy people. One of his channel-surfing buddies, Hilda Charlton, introduced him to Joya, a thirty-something Brooklyn Jewish housewife who fell into trances from doing “the yogi breath” in the bathtub for six hours as an appetite-reduction thing. Guess she was really hungry, and Samadhi was her only refuge. After falling into trances, she developed this problem of seeing “an old man with a blanket.” Hilda asked Ram Dass to see Joya, and just like catching a fever, dear old Ram Dass went head over heels for Joya. He decided the old man in the blanket was Neem Karoli Baba, so he got his guru back, because Joya was a channel. Better yet, she was a channel with huge capacity, a virtual spiritual television who could channel anyone from Crazy Horse to Mohandas Ghandi. Joya was a scandalous divine mother given to salty language and straight talk. A little bit of Dr. Laura, a little Leona Helmsley, and a lot of Helena Blavatsky. She grabbed Ram Dass and took him like an elevator straight to the top. She taught Ram Dass what it meant to have superstar status, and locked him into a lie – they were having sex, but publicly claimed to be celibate. There was of course a discovery, more discoveries, a coverup, a scandal, an explosion, an implosion, and egg all over Ram Dass’s face, as he admitted in his book Grist For the Mill.

Ram Dass’s complete failure to perform as a guru on an equal level with Trungpa, or as a partner with Joya, is omitted from the movie, and the filmmakers don’t ask Ram Dass about those years. I would have thought they merited as much attention as the silly “Millbrook experiment,” a free-floating assemblage of self-conceived geniuses dosing on acid in a groovy mansion owned by those signal exploiters of humanity, the Hitchcock-Mellons. Wow, utopia. Not. Leary and Alpert had just been kicked out of Harvard because they had given in to the desire to proselytize and liberate the chemical sacrament, as they conceived it. They had been giving LSD outside the parameters of their job authority, and were proving for everyone that LSD caused people to lose their sense of social reality. Indeed, the fact that both Leary and Alpert seemed totally fine with their disgrace was virtual proof that the drug they championed had caused them to lose the very rationality that had been the whole reason for being Harvard professors at all.

We can thank this incredibly stupid faux pas by the Leary-Alpert pair for giving the DEA a huge win in its effort to ban an expanding spectrum of mind drugs of every type, including traditional native medicines. But even after living through a lifetime and a near-death experience, Ram Dass doesn’t realize that by getting run out of Harvard in disgrace while sporting a silly acid smile, he squandered the opportunity to experiment legitimately with psychedelics in one of the world’s finest educational institutions. Instead of defaming psychedelics with his own childish behavior, proving unable to apply scientific protocols to a serious endeavor, he could have kept his head. He could have been more like the discoverer of LSD, Dr. Albert Hoffman, for example, who died recently, mourned by all, and fit as a fiddle until he stepped off the stage.

Ram Dass also seems a bit of a selfish child grown large. He seems willfully oblivious to the shock his abrupt decision to kamikaze his career must have given his father. Shock or no, Ram Dass’s father aged far better than his youngest son Richard. As has Ram Dass’s older brother William, a silver-haired, tanned gentleman. He reminisces briefly about how Richard once wrecked a brand new boat within seconds of taking control. The future guru manhandled the shifter, causing the boat to slam back and forth between the dock and another obstacle. That was all the boating they did that day. With a resigned note in his voice, William wraps up the story with an explanatory declaration — “That was Richard” — tilting his head, raising his brows, and twisting his mouth wryly in a tolerant expression.

Yes, that was Richard, the same Richard who returned from India as Ram Dass to host flocks of barefoot young people on the golf course adjacent to his father’s country estate. That was Richard, earnestly but self-impressedly telling the crowd through closed eyes, “Now, we will meditate … for about …” here pausing for a self-adoring smile, the better to select a mystic number, “seven minutes ...” No doubt seven minutes became the right amount of time to meditate for dozens of people that day. Richard, now Ram Dass, never realized how silly he must have looked to his relatives, and how sorry his brother must feel for him now. No wife, no kids, no one to care for him. Sure, he had a hell of a good ride, the incense smoke and the adulation, but it wasn’t very virile or very challenging, and now it’s tired, cold and lonely with a crew of hangers-on standing in for a family.

We Can Do This

The moviemakers are not very receptive to criticism of Ram Dass’s past or present personality or “teachings.” Ignoring the obvious fact that a great part of Ram Dass’s spiritual value to students and devotees has been crushed under God’s careless hammer, this film highlights the silver lining in the clouds that have engulfed Ram Dass in their darkness. The feel-good machine has to be turned on high to accomplish this transformation, but after all , what is the New Age all about but doing amazing things with film? As the movie maneuvers to a feel-good conclusion, the background music becomes more encouraging. Ram Dass, it turns out, has come out of his funk. He’s battling back against the paralysis, getting on his feet, blending his own arcane grief with the pedestrian sufferings of others. He is writing a book with a man who finishes his sentences, although at the beginning of the movie he said he prefers that people not finish his sentences. The “writing” process comes across, literally, as a charade. Ram Dass is trying to make his mind produce speech from thoughts that aren’t even fully there. The writer is sitting there putting words in his mouth, writing stuff down, just guessing what to say, and he has no gift for this – he knows he’s failing, but he keeps trying. After the writer manages to come up with a complete cheeseball of a closing line, Ram Dass, smiling beatifically the while, ekes out the comment, “You’re so … New York schmaltzy”. The writer backs up, exposed. Okay, we’ll just cut that last part, he volunteers. Ram Dass says no, let’s finish it. So it is finished, but when books are written this way, by civil negotiation between a wordsmith and an aphasic older gentleman formerly-famous for his metaphysical eloquence, something has gone seriously awry. Spiritual leadership has been redefined at this point. In Ram Dass, the New Age has found its Reagan, an old warrior venerated even in dotage. Reagan had Nancy. Ram Dass has the publishing industry.

Thanks to the publishing industry, Ram Dass has got his groove back, and in so getting it back, he echoes what Wavy Gravy says to the camera with total non-seriousness – he is going ahead of us baby boomers into the tunnel of aging, bringing back the information we need to make it through. We’re not going to be let down by this movie, I realize. It’s a recovery story. As the theme sweeps onward to its conclusion, Ram Dass is interviewed in front of a hall that is never quite shown to be full of people. Baby boomers, particularly women, come to say hello, to express deep warmth, to give hugs, and Ram Dass is back on his game. He’s talking better, and he has a new rap down. A somber moment falls when his caregiver rolls him out of the empty hall, shown in its unfillable expanse for the first time. It is a lonely moment.

What’s a little lame about Ram Dass’s recovery is how he doesn’t own the bummer he was on after he first recovered from the stroke. He blames it on other people – everybody around him thinking “poor Ram Dass,” causing him to believe their negativity. Okay, I don’t want to beat up on an old man trying to get through a very hard day such as Ram Dass faces daily. But at the beginning of the film Ram Dass said he’d been jolted by his failure to manifest spiritual awareness during imminent death, and was deeply grieved by mental and physical deficits resulting from brain damage. That’s enough for anybody to be entitled to be a little bleak of spirit, but it’s typical of Ram Dass’s willingness to rise to the role of role model that he preserves his image even under hellish circumstances. At this point, his time for naked honesty is past. He needs to survive and keep on, so he is now buying into the revisionist history constructed by his handlers.

Like a Hallmark greeting card that rises to any occasion, Fierce Grace tries to make everything all right. Doggedly, the producers plow on, attempting to show how Ram Dass is carrying on. He explains to the camera that he had lost faith, and reclaimed it when he realized how bleak life is without it, so again he's a believer. We can all breathe a sigh of relief. Ram Dass is saved from a permanent bummer, and we won’t have to digest his grief! But what Ram Dass believes in is a pretty vague quantity. His faith seems like a cup that’s been broken and glued back together – marginally functional and unable to bear ordinary use. It’s not entirely clear that it is an unalloyed pleasure for this old man to sing bhajans anymore. As he claps to the rhythm of a roomful of blue-state Americans singing Hindu holy songs, he gets a pained, confused look on his face. Behind closed eyes, Ram Dass seems to be digging for meaning, until he gives up the process, his emotions carry him away, and he starts to cry wretchedly. Throughout the uplifting singalong, Ram Dass’s face reveals difficult emotions, and he looks very little like the other devotees, affecting serene transports as their reward for devoted crooning. Among his many expressions, one recurs most often – ambiguous bewilderment – the look of a man who is trying to laugh along, but is not sure if he has exactly got the joke.

This is a big loss for everybody, because before his stroke, Ram Dass knew, and taught his beliefs with confidence. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus told his close disciples, “Ye are the salt of the earth. If the salt shall lose its savor, wherewith shall it be salted?” Jesus was telling his disciples that they had to be filled with faith, to communicate faith to others, just as salt must be salty to be of any use. Ram Dass was the salt – he communicated the flavor of the Buddho-hippie-Hindu-reincarnationist philosophy to all of us. By his own admission, however, he has slid considerably down the scale of relative saltiness. He isn’t very salty at all any more, in fact, he probably needs salt, but as the former saltiest man in America, where would he get a supply?

Despite the obvious fact that it’s time to scale down the myth to fit the reality, the makers of Fierce Grace have quite another story to tell. Ram Dass, they push us to believe, deserves continued veneration as a saint. However, they simultaneously disregard his true message, perhaps because Ram Dass isn’t consistent in communicating it, and really no one wants to hear it. Ram Dass’s true message was politically unacceptable for those in the religion business, so the filmmakers sweep it under the rug.

Instead of airing the truth that Ram Dass is disoriented by his brain damage, and is recovering from depression, the movie is intent on burnishing his credentials and piling up fuel to fire the funeral pyre of his legacy. For example, at the start of the movie, a couple from Ashland describes how Ram Dass’s letter to them after the sudden death of their daughter helped them heal from their bereavement. This scene seemed ill-conceived, like several others in the film. Granted that he wrote good consolatory correspondence with students, Ram Dass can no longer perform at that level of intellectual and emotional subtlety. Besides, what is the point of this bit of character-testimony? Obviously no one was willing to say he’d healed the blind or made the lame to walk, but why get into the competition at all? Perhaps because, with a bit of nostalgia, we can honeycoat this reality and pretend that, notwithstanding Ram Dass’s disheartening cry of pain and fear at the moment of his rude awakening, it is all okay. We’ll just crank up some emotional footage with guitar music to cover it up. Don’t worry folks, we can do this. Just close your eyes to reality, and the movie’s spin will take you to a good space where it’s “all good.”

A Diagnosis and Report of Cure

Reviewing the evidence, I would submit that Ram Dass suffered from a form of narcissism I have dubbed TIDS (“Tantra-Induced Delusional Syndrome”), a proposed entry for the Diagnostic Symptoms Manual for Mental Disorders. TIDS comes in three flavors – Student-Side, Guru-Side, and Transitional. Student-side TIDS causes the slavish, self-hating behavior typical of many cult adherents. Guru-side TIDS leads to a “god-realm” attitude in which internal and external events reinforce delusions of wisdom, greatness, goodness, and significance in the subject, who floats ever-higher on a spiral of self-reinforcing self-adulation. Transitional TIDS is an advanced stage of Student-side TIDS, in which the subject develops the delusion that they are turning into a guru, something that so rarely happens as to be discounted entirely from the realm of possibility. Transitional TIDS-sufferers are often highly energized and competitive, and thus are found in high levels of spiritual organizations, currying favor and partaking of the true Guru’s reflected glory, fancying themselves greater than they are ever likely to become.

While hardly anyone gets Guru-side TIDS without the aid of outside persons who “recognize” the spiritual genius within them, virtually no one recovers from it. The self-delusive lock is self-reinforcing. Having experienced the impossible pleasure of complete guru-hood, their minds just won’t go back. Even if Andrew Cohen ends up living in a dumpster, he will still think he’s a guru. But I think Ram Dass is off the high. At the start of the movie, Ram Dass was terribly put out because he failed to think of God at all, and became absorbed in the appearance of pipes on the ceiling above him. Perhaps if he’d been practicing “bare-awareness” meditation, this sterile perception wouldn’t have disturbed him so deeply, but Ram Dass was apparently expecting some confirmation of his beliefs when the death process began, and there was none. His Guru-side TIDS condition collapsed when it was punctured by the sharp point of reality.

The proof comes from a sad scene toward the end of the movie, shot with a young girl who has come to Ram Dass distraught over the murder of her activist boyfriend by a Central American death squad. Ram Dass tries to comfort her by saying that God doesn’t follow our desires, but he clumsily invokes as an example his own disappointment at being unable to do a radio show he’d been planning before he lost his mental capabilities. Most people would say that was an insensitive response to death – to compare not doing a radio show with never seeing your sweetheart again – and the girl’s face shows it. She seems to be wondering, “What the hell? This is helpful?” By the time Ram Dass blurted that malapropism, though, the interview had turned into a debacle. He had harvested a rejection when he tried to give the girl a flower. Smiling beatifically like a sweet old grandpa didn’t work either. This girl wanted answers to deep questions, and Ram Dass struggles to converse about everything. He said to her that “losing a lover is a path,” but that didn’t help. She told Ram Dass about a dream in which she communicated with her dead boyfriend, but with his limited vocabulary, Ram Dass could barely get out a crippled exclamation that evoked a rudimentary mental state: “Yummy! Oh, yum, yum!” It’s a tortured scene. Ram Dass can’t express himself clearly; the girl’s not getting any empathy; she’s having to cover for his frailties; the whole exchange is humiliating. Ram Dass breaks down. The young lady leaves after they exchange a cute hug and she gives him a kiss. Who the hell thought this was a good idea? Well, at any rate, his career as a guru is clearly at an end.

As a Guru-side TIDS sufferer, Ram Dass’s prognosis for recovery was terrible, but he beat the odds when the outer and inner framework supporting the delusion fell apart. From the outside, he lost the charming eloquence that made him a spiritual personality in modern media. He lost the chance to do a radio show. The few cooling embers of his career can’t get his kettle boiling. And on the inside, Ram Dass lost the illusion that he enjoyed for all the years when he thought that his spirit, independent of his body, would travel on into eternity to continue the joys of consciousness. He knows death is coming with a gun loaded with darkness that he can’t see into, and he doesn’t believe the pretty pictures he painted on the darkness for a lifetime. He is free from TIDS, and subject again to the normal constraints of humanity. But don’t try to tell the moviemakers. They’ve got TIDS themselves.

Ram Dass: Fierce Grace, directed by Mickey Lemle