WHAT IS BUDDHISM?, by Charles and Tara Carreon  Buddha Bugs Out

Buddha Bugs OutBuddha was born in Northern India in 563 B.C. His father was a small-time monarch of the Sakya clan, with big aspirations for his son to become a "universal monarch." An itinerant fortuneteller told the Buddha's father that while the government career path was a possibility for his son, he might also become a saint. Horrified by the latter notion, his father came up with the idea to marinate his son in every pleasure, and insulate him from every irritation, so that he would have no desire to escape worldly life; Buddha's father thus entombed the young prince in a pleasure warren. Legend has it that Buddha sneaked out in the palace limo and took a cruise around town, where he saw a decrepit senior citizen wheezing his last, a leper counting his missing fingers, a corpse with weeping mourners, and a monk who was the picture of serenity. Buddha apparently felt betrayed, like he'd been eating a yummy apple and discovered it was infested with disgusting worms. He considered his options -- and decided to go the monastic route. He cut off his long, beautiful hair that his mother loved so much, and left the palace like a thief in the night, hooking up with some rough trade at the outskirts of town that called themselves "yogis."

Buddha Rejects Spiritual AuthorityIn his quest for "enlightenment," Buddha studied the teachings of the the leading gurus, pandits and yogis then swarming the Indian jungles. While seeking enlightenment was a popular pastime, apparently Buddha found no successful practitioners, because he concluded none of the available teachers had found the goal. In this sense, Buddha might be considered the pickiest of spiritual shoppers, and indeed, an incredibly arrogant man. After all, this was India at the height of its spiritual development. The term "Rishi," had existed long before Buddha -- and monks, renunciates, fakirs, shiva and vaishnava babas were thick as flies in the holy centers, as they are today. Buddha jumped the fence, an impatient upstart who was probably secretly sneered at for being "the Prince," because of his royal upbringing.

Apparently running full-tilt for the psychological opposite of being a spoiled royal scion, Buddha became a severe ascetic . Stone carvings of the Buddha in his sixth year of renunciation show him in the advanced stages of anorexia nervosa, a diagnosis common in the children of overbearing, wealthy parents. Fortunately, he found the path to recovery. Buddha is said to have "renounced the ascetic path" after he realized the futility of starving the body to conquer the spirit.

Buddha Gets ItOf course, renouncing the ascetic path didn't mean he walked into town, had a drink at the tavern and checked out the chicks, like most Buddhists who are renouncing asceticism. Instead, he took "the Middle Way," and after having a good meal of rice pudding, sat down on a comfy cushion of grass under a ficus tree, and resolved to stay there until he achieved his goal. Frankly, this still sounds pretty austere to me, especially the part about staying there until he "achieved his goal." He hadn't done it in six years before then, and what was the magic of resolving to stay in one place? One might question how much he had really renounced asceticism, with this kind of resolve as his new point of departure, but fortunately, he attained enlightenment less than twenty four hours later, as he glimpsed the light of the morning star after a single night battling the demons of his own mind. If he hadn't succeeded that night, of course, he wouldn't be "Buddha" now, would he?

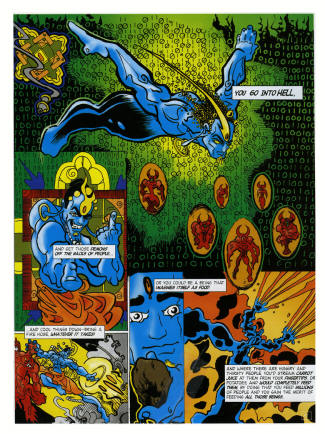

The demons of Buddha's own mind are personified as Mara in tradition. Mara assailed the budding Buddha first with hostile arrows of aggression that turned to flowers as they descended on the meditating sage. Frustrated, Mara loosed his beautiful daughters to work their charms upon Buddha, but again to no avail. Thus Buddha transcended hatred and desire. The Tibetans will also explain in detail how he transcended ignorance, pride and jealousy as well, resorting to tripartite and five-branched analyses, according to their various traditions. Suffice it to say, it was a big night for Buddha, and for all humanity when he sent Mara packing forever. Hallelujah!

Two thoughts occurred to Buddha after he attained enlightenment. "Wow, this is Great!" and "Nobody else will get it, or even believe it, so I won't tell anyone." We can understand both of these thoughts without being enlightened. Of course, getting enlightened has gotta be Great, otherwise it wouldn't be called getting enlightened. Next, India's swarming with sages who claim to offer paths to enlightenment -- there's gods everywhere decorating banyan trees and temples, but here, a mere six years after running away from his throne, this Sakya Prince is enlightened. You can imagine a lot of hash smoke being coughed out over that one! So naturally, he must have second thoughts about making his proclamation. According to legend, he was just going to keep mum about the whole thing and let his secret go to the grave with him, like some old pirate with a stash of treasure. According also to legend, the gods gave him a nudge, too, pointing out that they were interested in what he had to say, and actually there were a few bright people who might get it.

Buddha Converts The DoubtersThe first people Buddha met were his old pals, some fellow-anorexics who were still nursing their brittle bones and grasping at straws in the twilight of their meditative ignorance. They dumped all over Buddha, who by now was eating regular meals and looking chubby by ascetic standards. But he ripped right into them with his incisive analysis of their folly, and pretty soon he had picked up several new converts. They cut their hair and started eating and following the Buddha. They all remained celibate, though, and agreed to remain unemployed, making their living begging. Buddha called this The Middle Path. Makes sense, right? Not a breeder, not contributing to the economy, but not an ascetic. Just a guy who's free to be.

Buddha's Disciples Fail to Take NotesThe Buddha's disciples apparently never begged any pencil and paper from anyone, even though writing was actively practiced at the time in scholarly circles, and many of the early monks were scholarly. You might almost think someone had told them not to write anything down, because it took 300 years for them to even take a crack at it. Sort of a confidentiality agreement. Well, you can imagine after 300 years, memories varied considerably, depending on what part of the jungle you had been camped out in for the intervening centuries. Naturally, the Buddhists fell to disputing and haven't stopped since.

As A Result, They FightThe first big Buddhist dispute, and the main one today, is between the tight-assed people and the big-hearted people. The tight-assed people are called "Hinayanists" by the big-hearted people, who call themselves "Mahayanists." The Mahayanists are called "heretics" by the serious Hinayanists. Now that they are all here together in the USA, they try to paper over these disputes, but the enmity is mutual and long-running among true partisans of either disposition.

What They Fight AboutWhat is all the row about, though? Just this -- the Official Tight Assed Buddhists (Hinayanists) think that the Buddha really meant it when he said that in order to attain Nirvana you need to extinguish desire, and they go around trying to stamp it out wherever they find it. They shave their heads, bind their breasts, sit long hours trying to not want to stand up and move around, because after all, that's wanting something, which is the whole problem. They sort of try to strangle themselves to escape the pain of living, which is after all caused by breathing. Occasionally they attain mental states of great satisfaction similar to sheathing your entire body in a condom so you won't get contaminated by desire or other disturbing experiences. A Hinayanist is sure that everything will be all right if he can just stop being anyone at all. This is an excellent religion for trust funders on a budget, because you won't spend much on entertainment, or fall in love and blow all your cash raising a family. Actually, this sounds a lot like the religion the Buddha really would have founded, given his proclivities. Which may explain why the Hinayanists are so damned mad at the Mahayanists for hijacking their tidy little religion.

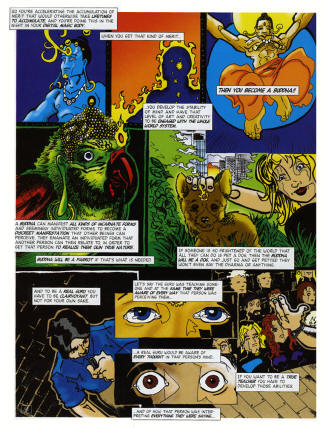

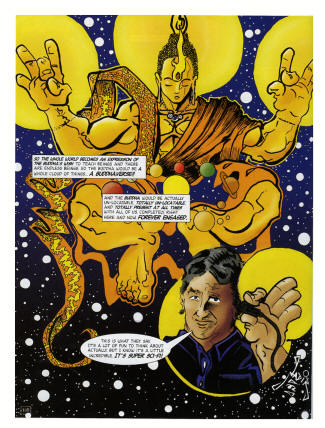

The big-hearted Mahayanists are all over the map with their doctrines, by comparison. But they all agree that the sort of cat-washing-itself style of meditation practiced by Hinayanists leads only to the minor spiritual achievement of "Arhat-ship," which is a classic of damning with faint praise. The real heavy freight-carriers in the big-hearted tradition are called Bodhisattvas, "heroes of enlightenment," and far from stopping to consider their own immediate release from suffering, they throw themselves immediately into the business of placing other sentient beings in the bosom of enlightenment, like firemen clearing out a burning building.

In practice, this leaves the Mahayana much greater scope for imaginative expression, and opens the door to a less prissy ethical approach. A Jew would always have to wonder if he was safe hiding from nazis in a Hinayanist's basement, who might feel compelled to tell the truth to keep his karma clean, but would feel comfortable hiding in a Mahayana basement, knowing that a Mahayanist would relish the opportunity to tell a meritorious lie. On the other hand, a Mahayanist might also find an excellent reason to screw your wife, for everyone's benefit. It's like that.

The most-often cited sources of Hinayana Buddhism are The Dhammapada and the Sutta-Pitaka. The practices of these Buddhists are often marketed in the U.S. as "vipassana" or "mindfulness" meditation, supplemented with the practice of "mehta," the cultivation of positive feeling toward all beings. These practices emphasize, at least at the beginning stages, reducing the traffic of conceptual thought by resting the mind on simple sensory stimuli, such as the feeling of your ass sitting on your cushion, or your diaphragm rising and falling with each breath. They really work. These practices have innumberable adherents, and are often presented with less packaging than Mahayana schools. There are probably lots of big-hearted Buddhists practicing under cover of the Hinayana method, ignoring their purported dispute with the Mahayana. On the other hand, the heartlands of Hinayana Buddhism are repressive regimes like Burma, and Sri Lanka. Thai Buddhists are also allegedly Hinayanist, but their food seems very big-hearted.

The resounding sources of Mahayana Buddhism are the early Chinese Ch'an Buddhist texts like The Sutra of Hui Neng and the Diamond Sutra, and the Third Zen Patriarch's Sutra on Faith in the Mind. These sutras are easy to understand once you stop trying too hard. To explain them here would not be half as helpful as for you to read them yourself, but in brief the idea is just this: the nature of your mind is clear and without substance, like space, and all of the experiences you have arise and subside within that clear nature, having no origin and leaving no trace. You are ultimately free, and have no need of anything. Everyone is in this same condition.

Since the Mahayanists burst out of the Hinayana coccoon, they have turned into all manner of butterflies, from the garish million-winged Tibetan doctrines to the simple moth-like Zennists who haunt Sung Dynasty ink paintings and Japanese Sumi sketches. Mahayanists have made a practice of virtually anything, encouraging people to memorize 100,000 stanza poems like the Lotus Sutra, then boiling the whole sutra down into a single phrase, that can be endlessly repeated as a mantra. Tantrics from Tibet and China created covens of sexual magic, and were repressed, sometimes with "extreme prejudice," to use CIA-speak, by their fellow-Mahayanists of a more blue-nosed orientation. Japanese Zen teachers blended the philosphy of "sudden enlightenment" with elements of Shinto and the ancient code of bushido, the warrior way, to create the most fearsome soldiers ever known. Remember the "Kami-kaze?" That means "the wind of the gods," the old Shinto gods, made more fearsome by the serene acceptance of eventual death, made deadly by the certainty that only honor, now, is worthy of protection. If you haven't run your finger along the sharp edge of military Zen, you haven't seen the full sweep of Buddhism in action.

Stuck At Step OneSo what did Buddha teach? What is the true Buddhist path? It depends on who you ask. The usual approach at this stage in the narrative is to start ticking off some numerical lists -- The Four Noble Truths, The Eightfold Path, the Twelve-fold Wheel of Interdependent Origination, the Five Skhandas, etcetera. If you get involved with the Tibetans, their lists start to proliferate like the United States Code, with subheadings, sub-subheadings and footnotes. We're not taking that route here, because we're gonna get stuck right at the First Noble Truth.

How do you deal with the ten thousand shouting doctrinal assertions? Our crazy idea is to emulate the Buddha -- to reject everything that everyone is selling and try to take a first look at the problem with our own eyes. Is there a problem?

Buddha said there was a problem, a huge, insurmountable problem. That is his First Noble Truth: Life Is Suffering. The next three Noble Truths assert that the Cause of Suffering is Desire, that Desire Can Be Stopped, and that The Eightfold Path Leads to Stopping Desire. This follows the ancient Vedic tradition of medical diagnosis -- "the patient has tonsilitis; the cause of tonsilitis is infection; the infection can be cured; and, the cure is the administration of streptomyicin."

Obviously, step one is to diagnose the disease correctly. So what do you think about Buddha's diagnosis? Before you accept his solution, I suggest you agree on the problem, eh? If you don't think life is suffering, you're on the wrong bus. Because this one's going to Nirvana, the end of the road, the last stop right after No Desire. Hardly anyone goes there. Still interested, or you wanna think it over?

Think of how much time people would save if they just thought about that. "Do I think all life is suffering?" Most people, being honest with themselves, would have to say, "Hell no, I love drinkin' and screwin' and eatin' good food and reading good books and watchin' Winona Ryder on TV, and I love Angelina Jolie and that Andy Kaufman was so funny -- whatever happened to him?" But once you become a Buddhist, you'll learn to lug around this heavy ball and chain of simulated misery with you everywhere. When people ask how you are, you'll smile like a weary Bodhisattva (or Arhat), point at your portable ball and chain, and shake your head in a mute sharing of knowledge. The wan smile that passes between you and your Buddhist brother will say it all, "Samsara," the painful cycle of life and death. But as soon as the other Buddhist walks away, you'll just deflate that ball and chain, pack it in the trunk and drive home not thinking about it again. You go back to being normal. Nobody can be that good all the time.

Until of course something awful actually does happen. Then it's flop back down on your meditation cushion, seeking shelter from the winds of your insane mind. You can see her flirting with that guy, god you hate him. Concentrate on your breath. In - out, in - out, in - out. Oh he is such a phony prick. Five minutes later, concentrate on your breath again. He has money. That's it, he's got money, and chicks always go for that. Being spiritual gets you nothing. Except of course inner peace. Concentrate on your breath. In - out, in - out.

And people complain about this all the time. They say, "Oh, I was so much happier before I started meditating. Now I just sit down and as soon as I try to control my mind, it goes crazy!" They view this as a problem, of course. They came to find inner peace and they got inner turmoil. Most teachers say, "stick with it, it will get better," and most of all they say, "actually, you are now simply becoming aware of how turbulent your mind always was." Frankly, I think this is bunk. Your mind will in fact become more turbulent when you start watching it, just like a three year old kid. The kid's mom will tell you, "Don't encourage him, or he'll never quiet down." When people meditate in the Buddhist fashion, it disturbs their natural way of being.

You know why? Because they were getting along just fine not watching their thoughts, or second-guessing their motivations. Things were actually going along okay. But they weren't satisfied with that, noooooo. They wanted to make their life incrementally better -- more peace, more happiness, less stress and fear. They wanted to improve the situation, but they didn't want to discover that the situation was fundamentally screwed up! I mean, my life has problems, but it's not so bad that I want to get rid of life itself. I just want fewer bad things to happen, and more pleasant things. A child wants more ice cream and TV. An adult male wants more money and sex. A budding young woman wants romance. People in jail want to be out -- they think they would be happy then -- but they get out and they're still unhappy, and they end up back in jail.

Most beginning Buddhists want to improve their view. They're a little subtler than the average guy, and they want to be freed from the turbulent flow of conflicting thoughts. They want to see their fellow beings with love and understanding, not poisoned by the flow of jealousy and hate. They credit themselves with being good people, with wanting good things, and they want to build on this foundation of goodness. They do not want to find out that their existing structure of thought is out of control, chaotic, and self-defeating.

Because of this, frankly, we are not on the same page with the Buddha. He was burned out on palace life, and burned out on spiritual life, too. And he knew we wouldn't understand his point of view. Remember, right at the beginning, after he realized Enlightenment, he almost didn't bother to teach. Why? Because we can't get on the same page with him.

Meditation will, perhaps, if practiced correctly, put us on the same page with Buddha. Because, while we are unhappy in part, but not wanting to discard the whole, he was fed up altogether, and relieved himself of his ignorance once and for all.

Buddha's First Noble Truth is usually translated as "Life is Suffering." But I really wonder. Because if that were the case, then suicide would be the solution, and universal annihilation of all life would be total success.

Let's go back and join our horny meditator, trying to watch his breath while chasing girls in his mind. What's this guy learning? He's learning that he can't escape his mind. This fact may make him very unhappy, but he will refuse to blame, or credit, Buddhism for his condition. Nope, he will blame his "inability to meditate." He will reject the conclusion that the data compels -- that his mind is suffering.

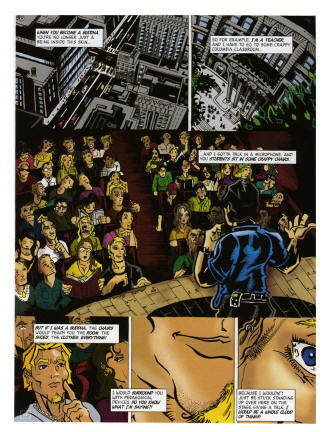

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, a Tibetan teacher, explained what this poor guy is going through:

We expect the teachings to solve all our problems; we expect to be provided with magical means to deal with our depressions, our aggressions, our sexual hangups. But to our surprise we begin to realize that this is not going to happen. It is very disappointing to realize that we must work on ourselves and our suffering rather than depend upon a savior or the magical power of yogic techniques. It is rather disappointing to realize that we have to give up our expectations rather than build on the basis of our preconceptions.

But this is not bad news. Through disappointment we make progress:

Such a series of disappointments inspires us to give up ambition. We fall down and down and down, until we touch the ground, until we relate with the basic sanity of earth. We become the lowest of the low, the smallest of the small, a grain of sand, perfectly simple, no expectations. When we are grounded, there is no room for dreaming or frivolous impulse, so our practice at last becomes workable.

And what is this mysterious "practice" he refers to? What is this grounding you get? You accept the First Noble Truth -- which I would prefer to express as "My Mind is Suffering." If you speed right past this point, and just go on trying to implement "the magical power of yogic techniques," you will blame "Life" or "The World" or "Samsara" for your suffering. You will think that Buddhism is your ally in the war against the ordinary existence we all live. You will think that nature, the force of procreation, sexual impulse, simple hunger and intellectual curiosity, are the problem. You will view innocent children as the hapless playthings of a cruel, manipulative force called "Life." You will try to stamp out your own impulses, thinking that this is how you put an end to suffering. And this is totally wrong. It is not Buddhism.

Getting to Second BaseIgnorance -- did someone say ignorance? When you accept that First Noble Truth, you discover your first level of ignorance -- you did not realize that your mind is the source of suffering. Initially, this is a very painful discovery, and you want to run away from the experience. Many people attempt to flee Buddhism at this point, and doctrinaire Buddhists do little to help, telling them that they just need to "tame their mind" and the magic will take over. It can be a lot like a bad psychedelic trip, a "no exit" situation that keeps ratcheting up to a higher level of tension, or like the mind state of a person who suddenly realizes they've been locked into their room, and keeps trying the door, becoming more desperate every time they find it still locked.

You're not going anywhere. The door really will not open. It is not even a door. You just painted it on the wall so you could think you could leave. You used to dream that you sometimes left, and went outside. But that was a dream. You may weep, realizing that you were dreaming all that time. You may miss the dreams, the illusion. You may wish you could go back, curse the Buddha, and take another path. Back into town, wherever, anywhere but here.

Depending on luck and disposition, you can make things a lot worse at this point. You may grimly force yourself to "face reality," by which you mean exerting continual effort to oppose the impulse to escape, and taking all of the "blame" for the unpleasantness. You may overdo it, thinking that the doctrinaire approach means denying that life has any pleasure in it, or labeling the pleasure as sinful. By doing this, you quite miss the point of the First Noble Truth, which merely defines the problem. To solve it, you must move on.

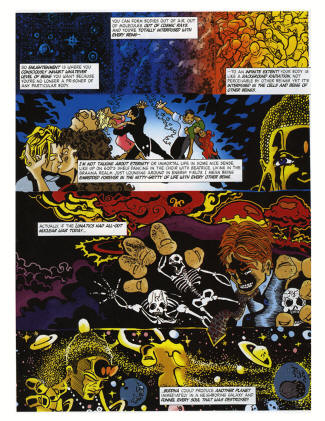

Moving on, you start to relax. You sit down, and use some simple techniques to just stay there. You sort of mature into the situation, becoming a "lifer." This is it. You believe it. And strangely enough, the dreams resume. A breath of ventilation sneaks in. The room becomes less solid. Light shines in. People come visit. Sounds disturb you. Sights intrude. You laugh. Suddenly you realize "I'm no worse off than I was before. I'm in exactly the same situation. I'm still having dreams, but I'm noticing that they're dreams." You realize, "I was all worked up over nothing! Of course it's all my mind. Of course I suffer because of my mind. Of course I enjoy because of my mind. And also, I am here." You laugh. "I am here."

And you will start to realize the meaning of the Second Noble Truth: "The Cause of Suffering is Desire." Because you will notice that whims, inclinations, notions, little wisps of desire, get you going. You're just sitting there in your cell, looking through the transparent walls, watching the ghosts come and go, and then you'll think, "I should go and do this or that." And you'll run down that mental path, and then you'll notice that everything's become quite solid again. Your dreams are so solid when you believe in them. Then you'll wake up in your cell, suffering. You cannot fail to observe the connection.

The Wheel StopsSo now we've found the culprit -- desire. So we pull out our telescopic rifle and sight in on the little devil. Pow! One more gone. That much closer to Nirvana, right? You can try it, and these varmint-hunter Buddhists can be found everywhere. They're about as good humored as ranchers who want to kill off all the coyotes and mountain lions. They figure their virtues are like tender calves that need to be protected from predatory emotions. So they put out poisoned meat, leg traps, whatever it takes. Their minds become mine-fields, and their meditation is like a fortified location. Inside, they're safe from desire, but it lurks everywhere around them, an enemy that will never be subdued.

Do not take this approach to The Third and Fourth Noble Truths, which taken together say that "Desire Can Be Stopped By Applying the Noble Eightfold Path." Because the force of desire is so vast and powerful that the ocean waves and the winds that howl through the mountains are weak by comparison. The force of desire, you will observe as you sit in your cell, is coextensive with your breath and your mind. Some traditions of Hindu mysticism say you need to actually stop breathing to stop thinking. It's probably true, but the Buddha tried that, and he always found he had to start breathing again. We do not stop desire by jamming a stick in Mother Nature's spokes, for she will blithely break all sticks.

At this point, more subtlety is needed. Just as we penetrated the notion of "life is suffering" to unearth "my mind is suffering," we need to take a look at the meaning of "stopping desire." Let's look. If we try to stop desire, first there is the concept of desire as separate from ourselves, then there is the notion of needing to end it, then there is the effort to end it. Hence the analogy of the varmint hunter, who sights, aims and shoots. If we turn from this outward-oriented analysis, and look at where desire truly resides -- inside ourselves -- we realize that stopping desire is going to be the biggest journey of self-understanding that can be made. For to find the foundation of desire within ourselves is to journey inward, seeking to understand what has animated our first movements, from when a baby first reaches for a mother's breast, or young people seek out their first sexual encounter.

We then regard desire far more tenderly. No metaphor of surgery or war is suitable here. Analogies to removing tumors and overcoming enemies abound in Buddhism. I reject them as misleading and violent. To stop desire is so much more subtle than that. For that part of us that "desires" is no small part, not even an expendable Siamese twin that we could kill and yet keep our own heart beating. Desire is inseparable from us like salt is inseparable from blood.

So what is this Eightfold Path that will end desire? Literally, it is a list of eight things that everyone does. We all have views, but if you have Right View, you will see your way to the end of desire. We all have intentions, but if you adopt Right Intention, it leads to the end of desire. Similarly, we can have Right Speech, Right Discipline, Right Work, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Meditation. Obviously, the important term here is "Right," and that is subject to interpretation, so let's get the best one we can, from Trungpa Rinpoche:

In order to see what this is, we first must understand what Buddha meant by "right." He did not mean to say right as opposed to wrong at all. He said "right" meaning "what is," being right without a concept of what is right. "Right" translates the Sanskrit samyak, which means "complete." Completeness needs no relative help, no support through comparison; it is self-sufficient. In a bar one says, "I would like a straight drink." Not diluted with club soda or water; you just have it straight. That is samyak. No dilutions, no concoctions -- just a straight drink. Buddha realized that life could be potent and delicious, positive and creative, and he realized that you do not need any concoctions with which to mix it. Life is a straight drink -- hot pleasure, hot pain, straightforward, one hundred percent.

Does this seem like no help at all? Like you should just go have a drink? It doesn't sound like this Buddhist would mind if you did, so by all means, don't let me stop you. Just come back and sip it while you read the rest of this, because it's actually going to tie up very conveniently.

Okay, got your drink? Let's just go back to our cell and see how this works. You stop seeing "out there," and start seeing the whole experience as "my world - my mind." That's part one. You start to get some ventilation, because you perforate the claustrophobia of being stuck "in here" and trying to get "out there." It's all in here. Then you find you have a modicum of control over what's in here. You can't stop desire, but you see it come and go. Sometimes you manage to sidestep an incoming impulse, and you laugh as it goes blindly by. Sometimes you see a huge roller of desire coming in, and you paddle out to meet it, and surf it all the way in, arriving wet and exhilirated. Your relationship with desire develops through acceptance, and surprisingly, you find yourself observing impulses with an unforced detachment that becomes more natural the more it develops. As you become accustomed to watching and experiencing your impulses, you will realize their wholesome, developmental aspect, because they no longer dictate your reality. Your cell, far from claustrophobic, will become interesting, intricate, fascinating, a laboratory for study, experiment, and discovery.

You don't have to do anything else except develop this comfort level with your reality. Right View? Just see it straight, and drop the preconceptions as you note them arising. Right Work? Just get out of bed and go do it. Right Meditation? Your cell is waiting. Right Effort? Just keep it up, without any frills or expectations. It's like sawing a piece of wood -- you don't have to visualize it cut in half -- just stroke it with the saw until it falls off.

The experience of living can begin again. Most of us in adulthood feel as if our learning and development ended about the time we left high school or college. Since then, it's been one disillusioning discovery after another. Travelling the Noble Eightfold Path is something like becoming a child again, because once we learn that our style of perceiving the world determines our experience, we realize we are best off using our mind in its fresh, unobstructed condition, allowing knowledge to stream in through our senses, and trusting the way in which the world takes shape in our mind. We see the painful sense of restraint felt by the mind trying to escape itself gradually diminishing. The Buddha says that by following the Right Path, our pain ultimately comes to an end -- for most of us it will be enough just to get pointed in the right direction.