A DAY IN THE LIFE OF PFC CHARLES CARREON, NINE YEARS OLD by Charles Carreon

You can't stay in bed, though the last thing you want to do when you hear that bugle racketing out reveille in the laundry room is get up. Dormitories one, four, and eight get serviced with a single raucous blast when the bugler stands in the laundry room all three share and cuts loose with the bright, awful notes you love to hate. Upstairs five and seven are getting the same treatment. Bleah! After listening to the steam duet for boiler and heating system all night long, forty-eight little boys lined up in three rows on army cots are hauling themselves out of bed, sneezing and looking groggy as only little boys can.

Charles was sneezing. He had no slippers, so every morning when his feet hit the cold, brown linoleum his body erupted into a sneezing fit. He was in row number two, so he had to get his bed made, sneezing all the while, before row number one came back from the bathroom. He tugged at the sheets, pulled the blankets tight over them, and made his corners carefully. He had just finished smoothing out his pillow when Miller, the officer for row two, a first lieutenant remarkably free of sadism, looking affable and relaxed in his crew cut and blue bathrobe, called out in a bored military tone "Row 2." Charles grabbed his toilet kit off the folding chair next to his bed and hurried into bathroom, managing to avoid being stopped by Sister Stephen or some observant officer for having no slippers.

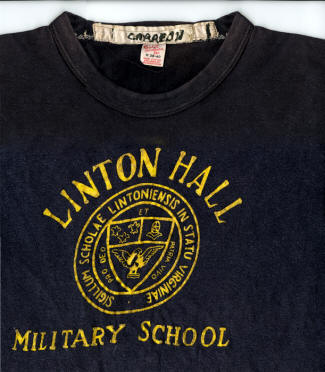

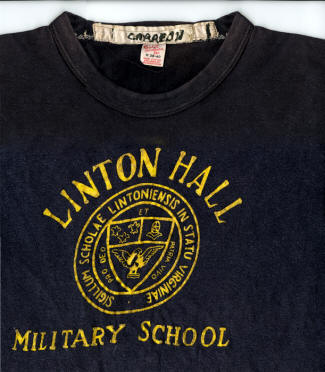

In the washroom there were seven sinks, a length of mirror, five toilets and two windows that let in the light of day. Charles took a sink next to the window. Warm water splashed into the shiny porcelain bowl, and Charles settled his arms into it up to the elbows, closing his eyes for a last sip of unconsciousness as the swirling warmth caressed his forearms. He came back quickly, as one does from such unauthorized naps, and splashed his face, checked his fingernails and teeth, and dried off. Looking in the mirror he saw a round face with a pug nose, a hairline with the widow's peak accented by the now-familiar crew-cut. Outside the window a mean wind was kicking the bare trees, smacking off the last few leaves and carrying them away. At least it was Tuesday; there would be no drill. Drill was a real torment, because you couldn't put your hands in your pockets and the temperature was officially between twenty five and eighteen, not considering the chill factor, and that sonofabitching Collins kicked you in the ass every time you got out of step till you were just marching along, freezing, gazing through your tears at the back of someone else's head. And it was Tuesday, and there would be no drill until tomorrow, and if he was lucky then it would be warm and he wouldn't get out of step. Oh shit he wished this damn winter would hurry up and get over with. The cool days of spring were so much easier, and after Military Day in May there was no drill at all, and you could spend the days with your friends as you pleased, eating popsicles in the black summer tee-shirts with gold lettering that were like the uniforms of freedom. But this day was like one link in a long chain of days, like one-step down a long, long hallway you had to walk the whole length of. At the end the gleaming, effusive light of summer shone through the institutional double doors thrown wide open, but right now there was the long, long walk that slowed you down like in dreams to where you thought you weren't moving at all, in time grown thick and sluggish, and were grateful just to get to the dining hall for breakfast.

The way they got to the dining hall was like this. In each dormitory the forty-eight boys would line up by the door in two files, and at the order of their dormitory leader, they headed for their stairs at a half step. They began at their own time, and Sisters stood on each of the landings to direct traffic. Soon the stairs were full of boys proceeding "in an orderly fashion," two hundred and fifty strong, in heavy cork-soled boots with two buckles that fastened above the ankles, wearing khaki pants, khaki shirts, black ties, and blue sweatshirts with gold lettering in a circular pattern. Their faces were clean, their hair didn't need combing, they kept their eyes straight ahead as they half-stepped down the stairs, in time with the whole, creating a sound that shook the building like an immense drum made of bricks and wood. In two files they proceeded down the hall from the opposite ends of the building, converging on the two entrances to the dining room. There they stopped, and filed quietly in.

Charles picked up a steel tray and held it out to the kitchen help on the other side of the bar. He got a pint of milk, two boxes of Puffa-Puffa Rice (registered trademark), two biscuits with butter, and a spoonful of peaches. Excitedly he whispered back in the line, "It's Puffa-Puffa Rice!" and soon everyone out in the hall knew it was Puffa-Puffa Rice.

As he carried his plate to the table he walked past the Commandant, a stocky, bullnecked ex-Marine Master Sergeant with military charm. He was smiling and talking to the Principal, Sister Mary David O.S.B. She stood tall and square in her black habit, and the stiff white brim of her veil was placed impeccably on a high, smooth forehead, accentuating the regal appearance of her clean eyebrows and strong cheekbones, her piercing eyes, and a high-bridged Roman nose that for sheer impressiveness has never been rivaled anywhere.

When she surveyed the boys with her calm, steely eyes, she seemed already to be swinging her paddle easily from side to side, as she did whenever there was business to be dispatched. Said to be from Richmond, Virginia, one would have sworn she was born in a sacristy, full-grown, from some strange, white Catholic egg. Charles sat down at a table with a group of friends.

"---Jeez," said Murphy, his black horn rims sliding down his nose as he chewed and talked, "I wish we could be in Dormitory One. They never miss their lunches (an evening treat), but Midge always takes ours away for some reason." We called Sister Stephen, blessed with a troll-like physique, Midge, short for "midget."

Referring to the missing lunches, Charles said, "She eats 'em." Despairingly, fat Villanueva responded, "How could she eat them all? She's got dozens of boxes in her room!"

The classrooms were at the far west end of the building, and boys were allowed to find their way to class individually, supervised only by the ringing of a bell. The windows of the sixth grade classroom looked up a hill, across the broad lawns, to the convent mostly hidden by a circle of trees. Charles was looking in that direction as old, fat, wire-spectacled, hunched-over Sister Bernadette, sweet in her boredom and rumpled black robes, began a class in History and Geography. That wind was still blowing, maybe they would open the gym, maybe it would be a good supper ... his thoughts roamed everywhere as he gazed out the window, played with the buckles on his boots, or leafed aimlessly through the big book, reading the captions under the illustrations that were meant to capture one's attention, but Charles just sucked the sugar off them and went on to the next one. Alligators in the everglades, wheat-fields in the Ukraine, steel mills and tugboats flowed through his mind as the class continued upstream under Sister Bernadette's dogged lead, with all the excitement of a barge-load of pig-iron.

The classroom was a sort of trap, a manufacturing place for future misery. Charles had never gotten fully into the idea of schooling; it jarred against him, he could not bring himself to study, to devote himself to absorbing facts that had no relationship to life as he saw it. He learned naturally, without effort, and he understood as little as an imbecile what all the fuss about learning was. He pretended to understand when teachers frowned and shook their heads about his talents going to waste, but he never really caught their idea. Pleasant, polite, bright and cheerful, he proceeded day after day to not do his homework, to daydream in class, and, when the mood was upon him, to play the clown. And this last, this playing the clown, this was the death of his innocence. As he learned to hide his academic laxity behind a show of humor, at the same time he learned shame, he learned the lie that his teachers believed, that he was indeed deficient, that he could and should do better, as if to join the plodding, memorizing crew of embryonic office workers were really the right path.

But he couldn't do it. It never was possible for him, because somewhere over his shoulder a little monkey was whispering in his ear, "Bullshit! Bullshit!" and kept him on his dreamer's road. The nuns watched him; they talked among themselves. His father was pushing. His earnest father who worked in a government job in Washington D.C. and wore his suits well, who smiled graciously, who had reserve, who inspired respect, was pushing. There in the classroom the days filled up with poor grades and carried him inexorably toward his father who stood imperiously at the end of a long tunnel with hand extended, waiting for the report card, the miserable scattering of C's, B's, D's, and occasionally, like a blot on the family name, a good stiff F. The monkey was never around when things got hot, when his father's hard judgments rained down on him like dark missiles and apologizing tears streamed forth without meaning or understanding.

After lunch Charles sat with Keiffer, a well-fed, friendly boy, who'd spent four years at Linton Hall already. Keiffer got along with everyone except the really tough older boys, who thought he was a sissy. Of course, he kind of was, and the nuns loved him for it. He spoke in a slight sing-song. His round lips curled gently and his cheeks were soft and round. He had an earnest way of going about whatever he was doing that only comes from being born into generations of bourgeois Northern European stock. Born to a harness which fits easily, not tempted by speed or freedom, Keiffer was in the stream. He followed orders that Charles could not hear. He sped up when it was required, he slowed down at the right moments. Charles could only marvel at this ability, which was far beyond him. It was nice to associate with such people, even if one couldn't be one.

When the bell rang, they lined up on the asphalt playground by classes and marched into the building, where the scent of supper was already drifting through the halls. Indefinite, it smelled slightly meaty, and the boys sniffed with interest as they marched past the empty dining hall, but could come to no sure conclusion. Sister Regina was already in the classroom when they arrived. Sister Regina had an incredibly ample and forward-pressing bosom, indeed her breasts pushed out so massively through the black folds of her habit that when one looked at her face it appeared at a certain distance, off beyond a hilly horizon. An imposing but kindly woman, she peered through her spectacles brightly, as if waiting to see a display of sincere interest in Science, which was her subject. Since there were no experiments to capture his attention, Charles read the book on his own, which gave him a fairly good grade in the class, since it was interesting reading.

After Sister Regina departed, Sister Bernadette returned to lead the Music class. Ciccone, an insolent kid from New Jersey with the air of a mafioso, was of course put out of the room for taking serious tunes like "The Eerie Canal" too lightly. So there he waited in the hall, unconcerned, till he was presently devoured by an ever-vigilant Sister Mary David O.S.B. At last school was over. Books were collected and put away. For a moment things hung in limbo, then the bell rang, and kids on two floors exploded out of their classrooms, poured through the hallways, and out of doors. It was a detonation which no one made the least effort to contain.

Outside Charles found most of his friends building a Dinkytown to populate with Stevens' set of authentic, antique Dinky-cars. Children lose themselves in a sandbox, moving piles of moist sand into formations that suit them, building and changing their minds, tearing things down and making them over again. Charles' mind was no different in this way, at least, from any other child's. He absorbed himself in the game, and didn't think of anything else for over an hour. Then he had to go to the bathroom. On the way there he saw Sebastian. Now Sebastian was an enigma. He never seemed to be obeying the rules, but he didn't seem to be punished for it either. Like right now one of his shoes was flapping its sole off. He looked like a circus clown and it was a blatant violation of the rules. Big deal, he didn't care. He'd glue it if he could. Amazing.

The bell rang a short time later, and they formed into lines on the blacktop by dormitories. The dormitory leaders gave their reports.

"Dormitory One, all present and accounted for, Sir! "

"Dormitory Two, all present and accounted for, Sir!"

And on down the line. The flag was lowered while the boys saluted and the bugler played Retreat. A solemn moment. The day's over.

The evening was good, not complicated by disciplinary problems. Sister Grace did not rage at them in the dining room for being too loud, nor did Sister Mary David find it necessary to shrill them to silence with her police whistle. Perhaps the nuns were in a good mood. Supper was the best it could be: boiled beef (not enough, though), mashed potatoes, mixed vegetables, milk and a slightly dry piece of chocolate cake.

Study hall was quiet. Charles read a book by Jacques Cousteau and dreamt of being a scuba diver, even though he couldn't swim.

Afterwards, in the dormitory they were blessed. They got their lunches and a full allotment of free time. Charles played chess with Villanueva while they chewed their mint-flavored jelly candy. Some of the livelier, inner city type kids played Motown 45's on a little portable record player. The game was a satisfying stalemate--they both enjoyed not losing. At eight-thirty, after the latrine call and bedtime prayers that Charles did not know, the lights went out, all except for the violet blue night light high on the wall next to the crucifix. In the laundry room the bugler played Taps, and the long drawn-out notes settled over the dormitories. Somewhere in the dark Charles knew that Villanueva was listening to the radio under his pillow, a tiny little transistor voice that whispered in his ear and told him of another world outside the walls of this strange place. In the darkness Charles would have liked a piece of bread, some bit of luxury to comfort him, but he always forgot to bring his own contraband. So it was time to go to sleep, and he lay there with his head on the white linen and thought of home and all that he would like to do, or eat, or see, he thought and thought, as children do, until he fell asleep.

Copyright 1982, Charles Carreon