"A considerable momentum for reform has been generated .... After previous investigations, the momentum was allowed to evaporate. The question now is: Will history repeat itself? Or does society finally realize that police corruption is a problem that must be dealt with and not just talked about every twenty years?"

-- Knapp Commission Report, December 26, 1972

Since the creation of this Commission, the Department has made important progress toward correcting its fundamental problems of corruption and corruption control. An anticorruption apparatus that had been allowed to collapse is being resurrected for the first time in a generation. On the investigative front, the Department has aggressively assisted this Commission recently in a number of cases we brought to its attention. In the 30th Precinct case, for example, Internal Affairs investigators worked side-by-side with Commission investigators, and federal and local prosecutors, to ferret out extensive corruption in the 30th Precinct. Commitment to uncovering the full extent of corruption there was unflinching. The Department now seems to recognize that the appearance of integrity is no longer more important than its reality.

The question now is -- as twenty years ago -- will this momentum for reform continue after this Commission has disbanded and public attention turns away from issues of police reform? History strongly suggests that there is little chance for an affirmative answer to that question unless the momentum for reform becomes institutionalized within and without the Department. The erosion of the Department's corruption controls is an inevitable consequence of its recurring reluctance to uncover corruption -- unless some countervailing pressure compels the Department to do what it naturally strays from doing. As happened in the wake of the Knapp Commission, the mere establishment of this Commission created such a pressure and commitment that improvement resulted. But the findings of this Commission also show that the vigilance of the last generation failed to survive the Department's natural desire to protect itself from scandal. Our challenge is to preserve the Department's new-found vigilance and commitment from the inimical forces of history.

For the past century, police corruption scandals in New York City have run in a regular twenty-year cycle of scandal, reform, backslide, and fresh scandal. In 1894, a New York State Senate Committee, known as the Lexow Committee, found systematic extortion and bribery among New York City police. Almost twenty years later, the Curran Committee, appointed by the New York City Board of Aldermen, found systemic police extortion of gambling and prostitution houses. Twenty years later, in 1932, Samuel Seabury, counsel to a State legislative committee, conducted an investigation that found widespread police extortion of gamblers and bootleggers. Two decades later, on September 15, 1950, the Kings County District Attorney's Office arrested Harry Gross, the leader of a large-scale gambling racket, who cooperated with the District Attorney and inculpated seventy-eight police officers for participating in an intricate and lucrative bribery scheme that included high-ranking members of the Department. In 1972, the Knapp Commission issued its Final Report that declared police corruption to be a standardized and Department-wide phenomenon.

How to break this cycle has been the focus of much of the Commission's deliberations. The Commission carefully considered a number of proposals aimed at institutionalizing a lasting commitment to integrity. Underlying our consideration of these proposals was our firm belief that the Department must remain chiefly responsible for policing itself if lasting reform is ever to be achieved. The fundamental principle that guided our deliberations is that the Department must deliver itself from the scourge of corruption. To allow otherwise will only renew complacency, diminish institutional accountability, and scuttle commitment to integrity.

We believe it is impossible for the Department to bear that responsibility without the help of independent external oversight. As history has taught us, the Department will always be vulnerable to the powerful internal pressure to avoid uncovering corruption. Only independent oversight will compel the Department to accomplish what it naturally wants to avoid: uncovering corruption among its own ranks. Only the existence of an independent, external, effective corruption control monitor outside the Department's chain of command will serve as a continuing pressure upon the Department to purge itself of corruption. At the same time such an independent monitor will serve to assure the public that corruption disclosures signal a vigilant Department rather than a wholesale failure of its integrity. Only such a permanent institutional structure, we believe, will break the historical cycle of scandal, reform, and backslide.

In determining the appropriate model for independent oversight, the Commission considered and rejected several models.

I. DEFICIENCIES OF THE OFFICE OF THE STATE SPECIAL PROSECUTOR MODEL

One such model was the Office of the State Special Prosecutor. The Special Prosecutor's Office was established at the recommendation of the Knapp Commission in September 1972. Contrary to the perception of many who have advocated reestablishing that office, the Special Prosecutor's functions were, in practice, limited primarily to prosecutions. It had no responsibility -- or authority -- to oversee or assess the effectiveness of the Department's corruption controls, and the conditions that allow corruption to flourish.

The Knapp Commission premised its recommendation of a Special Prosecutor on its fundamental belief that a principal concern in the fight against police corruption was the prosecutors. They found that because the District Attorneys depended largely on police officers to conduct investigations and prosecutions, they suffered from an inherent conflict of interest in bringing prosecutions against corrupt officers. That Commission also found that the close alliance between the Department and the District Attorneys caused great distrust among the public and honest police officers about the willingness of the District Attorneys to entertain and investigate allegations of police corruption.

This Commission does not believe that local or federal prosecutors are reluctant to investigate and prosecute corrupt police officers today. Nor have we found that the public typically questions prosecutors' ability to aggressively pursue such cases. On the contrary, we found that both federal and local prosecutors were eager for us to refer evidence of police corruption to their offices for prosecution and that they are moving forward based on our evidence.

Indeed, since the dissolution of the Special Prosecutor's Office in October 1990, the District Attorneys have committed resources and personnel to special corruption units dedicated exclusively to investigating and prosecuting official corruption. Some of the District Attorneys have even housed these units in locations away from their main office to encourage complainants and assure confidentiality. The District Attorneys have financed these measures from their own budgets despite not having received the additional funding that was to be redistributed to them from the budget of the Special Prosecutor's Office.

Some have suggested that the prosecutors' interest in police corruption cases began only after the creation of this Commission -- and only after police corruption cases became the center of public and media attention. While it is true that the number of police corruption prosecutions in our City increased after the establishment of this Commission, it does not appear that prosecutors ever refused to pursue corrupt police officers. We do not believe it necessary or desirable to supplant the authority of local prosecutors with yet another prosecutorial agency. We do believe it essential to devise a mechanism to sustain and heighten prosecutors' interest in police corruption after this Commission completes its work. The independent oversight model we recommend will help accomplish just that.

We would further note the fundamental problem with reinstituting the Special Prosecutor's Office is that it will not remedy the principal corruption control deficiencies we have identified. It is a tough-sounding idea that will not cure the problem. A Special Prosecutor's Office will -- by dint of its mandate -- do just as its name signifies, and no more: prosecute. While no one disputes that successful prosecutions of corrupt officers is a vital component of corruption control, it is not the exclusive one. As we have shown throughout this Report, effective corruption control must penetrate all operations of the Department and cannot depend solely on prosecutions. Quality prosecutions will do little to improve commitment, recruitment, screening, training, supervision, accountability and all the many other necessary ingredients of successful corruption control.

To achieve that goal, there must be continuous, external scrutiny of the patterns and causes of corruption, and the policies and procedures the Department employs to combat them. There must be regular inquiries and audits of such areas as recruitment, screening, training, supervision, police culture, and command accountability as well as methods of prevention and deterrence. The Department does not merely need more surgery to root out the cancer of corruption, it needs large doses of preventive medicine to insure that its commitment to integrity does not again atrophy. A prosecutor's office, by nature, simply cannot provide that kind of therapy. Since its mandate -- as well as its public reputation and budget -- will inevitably focus on its prosecution record, it will be dedicated to prosecuting rather than providing what the Department really needs. A Special Prosecutor will not insure that the Department conducts regular and aggressive integrity tests; that supervisors effectively oversee their subordinates; that commanders are held accountable for their willful blindness; or that conditions of police culture that nurture and conceal corruption disappear. For these reasons, the Commission concluded that the best remedy to deal effectively with the problem of police corruption would not be the recreation of a Special Prosecutor's office.

II. DEFICIENCIES OF THE INSPECTOR GENERAL MODEL

Another model that the Commission considered was the establishment of an Inspector General's Office to replace Internal Affairs in the investigation of corruption within the Department. Some urge that the Department has consistently demonstrated its inability and unwillingness to police itself successfully -- and should therefore no longer have the responsibility or authority to do so. The creation of an inspector general, many asserted, was the only way to root out corruption that the Department naturally prefers to minimize or conceal. All levels of government, they point out, have recognized the value of an independent inspector general. Virtually all federal, state, and local agencies are investigated by an inspector general's office that is independent from the agency it oversees. In New York City, in particular, the Department of Investigation employs a cadre of independent inspectors general responsible for investigating corruption in every City agency -- except the Police Department. It is urged that the Department no longer remain the exception to the rule of independent investigative oversight.

While we are convinced of the necessity of independent oversight, we rejected the Inspector General proposal because it wholly strips the Department of its capacity -- and, most important, its responsibility -- to investigate itself. We believe that the Police Department is the entity best able to prevent and investigate corruption among its members. It is the Department that best understands the corruption hazards facing cops, the culture that protects it, and the methods that can most effectively uncover it. The challenge is to devise a structure that compels the Department to do just that. The Inspector General model does just the opposite: it lets the Department off the hook in the battle against corruption, and eliminates its accountability for battling it successfully. Corruption would no longer be the Department's problem, but the Inspector General's problem. The fight against corruption can only be won if the Department itself is committed to aggressively investigate and uproot corruption on all fronts. We believe the dual-track model that we propose will insure that the Department does just that.

III. THE COMMISSION'S PROPOSED INDEPENDENT OVERSIGHT MODEL

Combining these two necessary principles of lasting reform -- independent oversight and command accountability -- was the challenge we faced in formulating a means to make vigilance and zeal enduring features of the Department's internal integrity controls. An effective program of reform must both heighten the Department's ability and will to combat corruption internally, and must create an external independent mechanism to insure that such ability and will do not meet a quick demise.

The Commission therefore urges a dual-track strategy for improving police corruption controls. The first track, addressed in Chapter Five, focuses on strengthening the Department's entire anti-corruption apparatus with equal emphasis on improving the quality of recruits, enhancing police training, strengthening supervision, upgrading methods of prevention, strengthening internal investigations, enforcing command accountability, and attacking the root causes and conditions that spawn corrupt acts.

The second track urges the creation of a permanent external Police Commission, independent of the Department to: (i) perform continuous assessments and audits of the Department's systems for preventing, detecting, and investigating corruption; (ii) assist the Department in implementing programs and policies to eliminate the values and attitudes that nurture corruption; (iii) insure a successful system of command accountability; and (iv) conduct, when necessary, its own corruption investigations to examine the state of police corruption. This Police Commission would make recommendations for improving the Department's integrity and will deliver periodic reports of its findings and recommendations to the Mayor and the Police Commissioner for appropriate action. In essence, the Police Commission would serve as a management tool for the Mayor and Police Commissioner, and a watchdog for the public. It would identify problems of police corruption and corruption control that need immediate attention and insure that the Department will not again fall victim to the pressures that work to corrupt its anti-corruption systems.

The Police Commission must have its own investigative capacity to carry out its mission of gauging the state of corruption, assessing corruption controls, and identifying corruption hazards. It must be empowered to conduct its own intelligence gathering operations, self-initiated investigations, and integrity tests. But, unlike a traditional inspector general, this capacity is not meant to replace the Department's or other law enforcement corruption efforts. On the contrary, it is designed to insure that the Department continues to police itself effectively by aggressively pursuing corruption where it likely exists and that it becomes -- for the first time -- accountable for doing so to an authority outside its own chain of command. At the same time, such an arrangement leaves the responsibility for corruption control clearly with the Department, without the risk of blurred responsibility or institutional buck-passing that might result from the creation of a special prosecutor or inspector general.

The power to undertake investigations is crucial to the Police Commission's task of insuring the high performance of integrity controls and the swift identification of corruption trends. During the course of this Commission's work, for example, we observed a number of police commands with substantial corruption hazards that Internal Affairs had made little or no effort to investigate. Having an investigative staff allowed us to probe some of those commands and thereby compel Internal Affairs to undertake a full-blown investigation or risk having the Commission bring a case to fruition without its participation. We found that this strategy quickly motivated the Department's anti-corruption machinery. Without such a capacity, we believe it unlikely that the Department would have responded to the Commission's evidence -- or attempted to generate its own -- as quickly or aggressively as it did. The new Police Commission, moreover, will insure that evidence of corruption is promptly referred to the appropriate prosecutor with whom it would cooperate and monitor the progress of the prosecution. In that way, it will help produce swift and certain prosecution of corruption without the need for a special prosecutor.

The Police Commission's investigative capacity, furthermore, is necessary to provide the Mayor and the Police Commissioner with the ability to call upon an independent agency to assist in conducting special projects or investigations. For example, if a high-ranking member of the Department or an Internal Affairs official is implicated in wrongdoing, the Mayor or Police Commissioner could call for the participation of Police Commission investigators to insure the integrity of the investigation. The Police Commission should also assist the Department to conduct command accountability inquiries in the wake of corruption disclosures, such as in the 30th Precinct, and insure that favoritism and Department politics play no role in determining the management or supervisory failures of police commanders. By having an investigative arm, therefore, the Police Commission can provide the Mayor and Police Commissioner with an independent look at a variety of corruption issues without having to depend exclusively on information from within the Department's own chain of command.

At the same time, we are mindful of the fiscal restraints under which the City must operate. We do not recommend the creation of a large and costly bureaucracy. We recommend that the new Police Commission be headed by five reputable and knowledgeable citizens appointed by the Mayor who will serve pro bono. We further recommend that the Commissioners have a limited, staggered term of office to guarantee turnover, avoid staleness, and prevent the development of a long-term bureaucratic relationship with the Department that could compromise the Police Commission's independence.

To accomplish its tasks, the Police Commission should have unrestricted access to the Department's records and personnel. It should have the power to subpoena witnesses and documents; the power to administer oaths and take testimony in private and public hearings; and the power to grant use immunity.

With the aforementioned powers, the Police Commission could perform its work, as did this Commission, with a small staff of approximately ten to fifteen people with varied expertise, including attorneys, investigators, police management experts, and organizational and statistical analysts. To the extent additional personnel is required, the Police Commission should be free to draw upon the resources of other agencies on an as needed basis, as this Commission has done.

The Police Commission must cooperate with and assist the Police Commissioner to implement and evaluate integrity programs and policies, neutralize the corruptive effects of police culture, maintain strong accountability among commanders, and enhance productive relationships with the community.

As we set forth in our Interim Report, the Police Commission should assume a variety of functions in overseeing the policies and procedures for preventing and detecting police corruption. The Police Commission's oversight and reporting duties will focus primarily on the following three areas:

Monitoring Performance or Anti-Corruption Systems

The Police Commission should:

• undertake studies and analyses to assess the quality of the Department's corruption controls;

• insure that the Department has effective methods for receiving and recording corruption allegations and assuring the confidentiality of complainants and witnesses;

• insure that the Department performs regular and effective corruption trend analyses that are used to identify areas for self-initiated investigations;

• assess the quality of investigative resources and personnel, and insure that the Department employs effective methods and management in conducting corruption investigations;

• insure that the Department consistently uses pro-active investigatory techniques and no longer relies on a reactive investigative system that narrowly focuses corruption investigations on isolated complaints and individual officers;

• insure that the Department has successful intelligence-gathering systems in place, such as effective undercover, field associate, and integrity testing programs;

• evaluate Department policy concerning command accountability and supervision, including levels and quality of first-line supervision, training of supervisors and integrity history in determining assignments and promotions;

• insure the Department involves field commanders, supervisors, and integrity control officers in corruption investigations and enlists their assistance;

• insure that the Department successfully enforces a system of command accountability;

• insure that Internal Affairs maintains a productive liaison with field commanders about corruption hazards and corruption prevention within their commands;

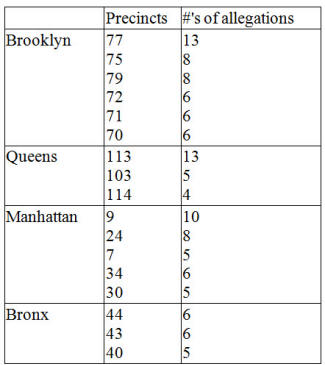

• require the Department to produce reports on police corruption and corruption trends including, analysis of the number of complaints investigated and the disposition of those complaints, the number of arrests and referrals for prosecution, and the number of Department disciplinary proceedings and the sanctions imposed; and

• conduct performance tests and inspections of the Department's anti-corruption units and programs to guarantee that the Department continually enhances its capacity to police itself.

Monitoring Cultural Conditions

The Police Commission should:

• undertake studies and analyses of the impact of police culture on matters of integrity;

• insure that the Department acknowledges and makes efforts to reform the conditions and attitudes that nurture and perpetuate corruption;

• assess the effectiveness of recruit education, integrity training, field training operations, in-service training programs, and the integrity standards set by supervisors;

• insure that the Department works to eliminate corruption tolerance and the code of silence;

• evaluate the Department's efforts to overcome police attitudes that isolate them from the public and often create the appearance of a hostile and corrupt police force;

• evaluate Department efforts to pursue and uncover brutality and other civil rights violations and their connection to corruption;

• investigate whether the Department routinely assigns officers with discipline problems to only certain commands within the Department, such as high-crime, minority precincts;

• evaluate the effectiveness of the Department's drug and alcohol abuse policies, prevention treatment, and detection efforts; and

• maintain liaison with community groups and precinct community councils to provide the Department with input from the public about their perception of police corruption and to obtain information for the Commission's recommendations for reform.

Monitoring Corruption Trends

The Police Commission should:

• identify through intelligence sources and integrity tests patterns of corruption and corruption-prone officers and commands;

• evaluate and report to the Department the extent of complicity in detected police corruption among fellow officers and supervisors, either by their participation in corrupt acts or by their silence; and

• conduct any investigation or inquiry into corruption or corruption-related issues as requested by the Mayor or Police Commissioner.

Conclusion

The consequences of police corruption are devastating for our police officers, our government, and our society. When charges of corruption are levelled at the police, we as a society are justifiably alarmed and become cynical about the rule of law. And rightly so. With crime uppermost on the minds of citizens today, we look to our police more than ever as our primary protectors. When the integrity and commitment of the police are called into question, the community is doubly harmed. When police credibility is tarnished, officers' ability to enforce the law is hampered on the streets and in the courtrooms. Cooperation and mutual respect between the public and the police are vital to effective law enforcement. When that erodes, so too does the Department's ability to fight crime. A foundation of our criminal justice system thus begins to crumble.

The community is further harmed because we lose the peace of mind we depend on law enforcement to provide, especially when crime and violence are rampant. When we learn that police officers are more interested in profiting from the community than protecting it, our confidence in the Department's ability to protect us understandably wanes.

And so it is incumbent on the public to continue to demand that the Department and our elected officials do everything necessary to insure the integrity of our police. The creation of a permanent independent police monitor will fulfill that responsibility.

But it is still the Department's vast majority of honest and dedicated officers who have the greatest incentive -- and ability -- to insure the Department's lasting integrity. It is they who know where corruption might exist; it is they who suffer the most immediate consequences of their colleagues' corruption; and it is they who can best help uproot it. For these reasons, the honest officer, most of all, must work to stop corruption or be prepared to feel the quiet pain expressed by lieutenant Robert McKenna during the Commission's public hearings:

But you know what really hurts? It's when he [the honest officer] goes to pick up his kids from school. Because parents talk, kids listen; they're at school, they talk among themselves. A little kid comes in, he sits in the back seat. He's got bright eyes and he looks at his Daddy. He says, 'Daddy, do you steal money?' The cop's stomach tightens. Some cops cry silently. Others just wish it was a bad dream, and it'll go away.

It is the Commission's hope, and belief, that this Report's findings and recommendations will put an end to that bad dream for the people of our City, for our police officers, and for our children -- both today and in generations to come.