PART 1 OF 2

EXHIBIT EIGHTTHE FAILURE TO APPREHEND MICHAEL DOWD: THE DOWD CASE REVISITEDThe question of how Michael Dowd and other police officers of the 75th Precinct could have perpetrated their corruption for so long with impunity provides a most glaring example of the recent failures of the Police Department's corruption controls. From 1986 through 1992, the Department's Internal Affairs Division ("IAD") received sixteen separate allegations implicating Michael Dowd and his associates. After six years of investigations, every case against Dowd was closed as unsubstantiated, despite the overwhelming evidence that Dowd often acted openly and notoriously and that large numbers of Dowd's fellow officers and supervisors were aware -- or at least strongly suspected -- that he was corrupt.

In November 1992, the Department provided its answer to the Dowd debacle. The Police Commissioner's Report into the conduct of the Dowd case blamed the Department's failure to apprehend Dowd on a flawed investigative organization that hindered communication and coordination between the Internal Affairs Division and the Brooklyn North Field Internal Affairs Unit ("FIAU").

This Commission came to a very different conclusion. In our view of the evidence, the Dowd case demonstrates a willful effort on the part of Internal Affairs commanders to impede an investigation that might have uncovered widespread corruption in the 75th Precinct. For reasons that cannot be attributed simply to a bad system of case management, in the course of the Dowd investigation, Internal Affairs fragmented corruption allegations, withheld critical information, denied access to crucial witnesses, and refused to provide essential resources to the FIAU. By doing so, Internal Affairs commanders doomed any hope of a successful investigation of Dowd and other corrupt officers of the 75th Precinct.

To understand how this could have happened, we must understand the attitude that afflicted IAD during the years following a notorious corruption scandal of the mid-1980s.

According to a number of police officers, police commanders, and ranking IAD officers who spoke to the Commission both on and off the record, the 77th Precinct scandal of 1986 -- and the Police Commissioner's response to it -- were the seedbed of the failures of the Department's corruption controls. These events sent a clear message that the Department's reputation could not afford to suffer another large-scale corruption scandal. Police commanders, who observed this scandal's consequences to the borough commander, Assistant Chief DeForrest Taylor and his subordinates, clearly understood that the disclosure of corruption on their watch could harm their careers. [1] A number of IAD officers we interviewed told us that after the 77th Precinct case an unwritten policy developed at IAD to avoid large-scale corruption investigations and publicized arrests that would embarrass the Department and ruin careers. According to these witnesses, this policy started at the top of the Department's command structure, in fact, with the Police Commissioner himself.

At the Commission's public hearings, Daniel F. Sullivan, the Department's Chief of the Inspectional Services Bureau from 1986 to 1992 confirmed what we heard from his subordinates. He testified that after the 77th Precinct case, a climate of reluctance infected internal investigators and field commanders causing them to avoid aggressive pursuit of corruption allegations. He testified that the Department had become "paranoid" about the bad press that revelations of corruption inevitably bring. He testified that the biggest hindrance to investigating corruption was the Department's unwillingness to suffer the negative publicity corruption cases inevitably bring.

That message filtered down from Sullivan to the Department's corruption investigators. IAD and FIAU investigators told the Commission about corruption investigations thwarted by the unwritten rule that patterns of corruption allegations reflecting potentially large-scale corruption problems should be fragmented into individual allegations reflecting isolated incidents. Lieutenant Lawrence Hotaling, for example, spent seven years as an IAD investigator and supervisor. He was an IAD officer during the 77th Precinct investigation and served as a supervisor of IAD's Staff Supervisory Unit, the unit that monitored the investigations of Michael Dowd and other corruption investigations in Brooklyn North. In July 1992, Hotaling told former Commissioner Kelly about IAD's reluctance to pursue broadly based corruption investigations. In a recorded interview Hotaling told Kelly:

What I feel happened is that, whether it was valid or not, it was running through Internal Affairs that the Police Commissioner was not too thrilled with the newspaper articles and everything about the 77 [Precinct]. And this, basically, this [Dowd's] crew had a 75 [Precinct] connection and there was a good possibility it [the 75th precinct investigation] could have blown up as big, if not bigger than the 77. It appeared from my perspective that they [IAD's commanders] were just trying to fragment the investigations so that it wouldn't all look like it's one big situation.

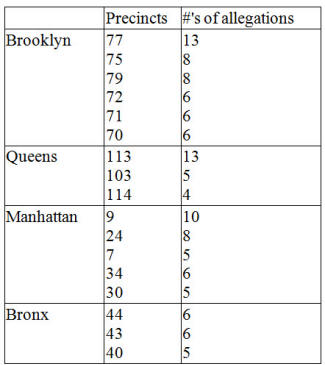

What made this unwritten policy even more dangerous to the public and the Department itself is that Commissioner Ward had reason to know that the 77th Precinct was not the only potentially widespread corruption problem facing the Department in the mid-1980s. Shortly before the 77th Precinct indictments were announced, the Special Prosecutor, Charles J. Hynes, met with Ward to discuss other commands where drug-related corruption might be flourishing. Hynes presented Ward with an analysis done by his office listing seventeen precincts in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, where the volume of drug corruption allegations indicated the need for additional IAD investigations. High atop the list was the 75th Precinct (See Exhibit A).

According to Hynes, Ward refused to approve any additional corruption investigations. In Hynes's view, Ward's response was not the result of a weak resolve to stop corruption, but arose from his unshakable belief that further corruption revelations would cripple the Department's ability to perform its job. Whatever the motivation, the Commission has concluded that Commissioner Ward and Chief Sullivan -- by their action or inaction -- created an unmistakable policy to avoid corruption scandals.

The Brooklyn North FIAUUnder these circumstances, Sergeant Joseph Trimboli joined the Patrol Borough Brooklyn North Field Internal Affairs Unit ("PBBN/FIAU") in 1986. As an FIAU investigator, Trimboli had the duty of conducting corruption investigations within the eleven precincts of the Brooklyn North Patrol Borough. His unit, like all FIAUs, reported to two separate supervisors: IAD and the borough commander.

Although the FIAU reported in the first instance to the borough commander, the bulk of its corruption case assignments came from IAD. IAD was supposed to act as the central intelligence-gathering and investigative body of the Department's internal investigations system. IAD received all complaints and allegations of corruption, processed them for administrative and intelligence purposes, and assigned the case for investigation. IAD's commanding officer, or executive officer, had the unbridled discretion to retain corruption allegations for investigation by IAD or to assign them out to the appropriate FIAU where they became the primary responsibility of the borough commander. Nonetheless, IAD was supposed to retain for investigation: (i) especially serious or complex allegations; (ii) allegations that crossed command lines; (iii) allegations against high-ranking police officials; (iv) allegations against members of IAD itself; and (v) any other allegation that involved particularly sensitive aspects of police work.

In addition, if IAD assigned an investigation to an FIAU, it had the responsibility to insure the quality of the FIAU's investigation. Through its Staff Supervisory Unit, IAD was supposed to review and evaluate the FIAU's investigation and provide it with guidance and assistance. In fact, if IAD was dissatisfied with an FIAU's investigation, it had the power to take over the investigation, re-investigate the case on its own, or conduct a parallel investigation to insure the FIAU did a thorough and professional job.

When Trimboli joined the PBBN /FIAU, he knew he was in for a busy time. According to Trimboli and many other police officers interviewed by the Commission, the Brooklyn North Patrol Borough had a Department-wide reputation as a command filled with hardened cops, crime-ridden neighborhoods, and plentiful opportunities for corruption. Brooklyn North had, and continues to have, one of the highest volume of corruption complaints under investigation at any given time.

Despite this situation, the PBBN /FIAU had neither the personnel nor the resources to do its job effectively and yet IAD -- whose commanders were fully aware of these circumstances -- continued to assign it serious and complex corruption cases. In the period from 1986 to 1992, the PBBN/FIAU had an average of eighteen investigators, each handling an average of twenty-five cases at any one time -- an impossible task for any investigator. At the same time, IAD and FIAU supervisors pressured investigators to close cases and reduce backlog.

The basic equipment necessary to conduct police corruption investigations was simply not available. As Trimboli put it, in his seven years in PBBN/FIAU all he had available on a consistent basis was "a pair of binoculars, a camera and a paper shredder." Even more disturbing, no help or additional resources was ever forthcoming either from IAD or the borough commander. Simply put, the paltry resources and unmanageable workload of the FIAU indicated to Trimboli and other corruption investigators we interviewed that corruption fighting was plainly not a high priority of the Department's bosses. According to them, internal investigators were, for the most part, "paper pushers" -- getting investigations closed for the record-keepers -- rather than serious corruption fighters. And worse, no one seemed to care.

Trimboli and the 75th PrecinctTrimboli's first encounter with corruption in the 75th Precinct came in 1986. The subject of his investigation was Police Officer Michael Dowd.

On March 4, 1986, the PBBN/FIAU opened a case on Dowd and his partner Gerard Dubois (corruption case no. 86-0449) based on an allegation received from the 75th Precinct's commanding officer, Deputy Inspector Kevin Farrell, [2] that Dowd and Dubois stole money from drug dealers, prisoners, and deceased persons. The investigation was assigned to Sergeant Trimboli.

Although this was the first allegation against Dowd for drug-related corruption, Dowd already had a history of misconduct. In 1985, IAD assigned two investigations against Dowd to the PBBN/FIAU, one for harassing and threatening his girlfriend (who later became his wife) (corruption case no. 85-0183) and the other for engaging in sexual acts with prostitutes in Bailey's Bar (corruption case no. 85-2532) where Dowd and his colleagues often socialized and discussed their corrupt deeds. Both of those investigations were closed as unsubstantiated.

By Dowd's admissions to Commission investigators, by March 1986, Dowd and his "crew," including Officers Dubois, Henry "Chickie" Guevara, Jeffrey Guzzo, Brian Spencer, Walter Yurkiw, Henry Jackson, and others had for over a year already become routinely involved in drug corruption by stealing money and drugs from street dealers, radio run locations, and by "scoring" (stealing) almost every opportunity that presented itself. Yet, it took over a year for internal investigators to begin their first drug-related investigation of Dowd. In fact, just four days after the initiation of the Dowd and Dubois investigation, IAD assigned the PBBN/FIAU another investigation into allegations of brutality by Dowd, Guevara, Guzzo, and other 75th Precinct officers (corruption case 86-0039).

Obviously, the Department's intelligence-gathering system had fallen down on the job, even though suspicions about Dowd's and Dubois's conduct circulated among officers and supervisors of the 75th precinct, including the precinct's commanding officer, Deputy Inspector Farrell. After all, it was Farrell who reported Dowd and Dubois to IAD in March 1986; and in June 1986, he assigned both Dowd and Dubois to the Coney Island Summer Detail, a well-known "dumping ground" used by police commanders to get discipline problems out of their commands and beyond their responsibility -- at least for the summer. Interestingly, when questioned by Commission investigators, (now) Deputy Chief Farrell denied any knowledge of a corruption problem within the 75th Precinct during his tenure. Even when shown the corruption log documenting his report to IAD, Farrell still claimed to have no recollection of making any allegation against Dowd, Dubois, or any other officer in that command.

Trimboli's investigation into Dowd and Dubois continued when Dowd returned to duty in the 75th Precinct in September 1986. [3] The investigation was closed in April 1987. Although it failed to substantiate the original drug-related allegations, Trimboli observed Dowd and his new temporary partner, Walter Yurkiw, engage in several patrol violations while on duty. As a result, Yurkiw received a Command Discipline; [4] Dowd pleaded guilty to charges of being off post and failure to safeguard his Department radio. He received a penalty of eight forfeited vacation days. Despite his years of corruption and crime as a police officer, eight forfeited vacation days represents the only penalty -- other than a single command discipline -- that the Department ever imposed on Dowd until his arrest in May, 1992.

The R&T Grocery Store RobberyAlthough Trimboli had not known Yurkiw before 1986, it was Yurkiw who put Trimboli back on Dowd's trail in the Summer of 1988. On the evening of July 1, 1988, Yurkiw along with 75th Precinct police officer, Jeffrey Guzzo, and former 75th Precinct police officer Chickie Guevara robbed at gun point the R&T Grocery Store, a drug location on Livonia Avenue in the 75th Precinct. After the robbery, Yurkiw reported for duty at the 75th Precinct leaving the car he and his accomplices used in a nearby parking lot with proceeds of the robbery sitting in plain view. Only hours later, officers of the 75th Precinct's Robbery Unit took Yurkiw into custody and the commanding officer of PBBN/FIAU, Captain (now Deputy Inspector) Stephen Friedland, responded to the precinct. The next morning, at the direction of IAD's commanding officer, Assistant Chief John Moran, an IAD investigations unit under the command of Captain (now Deputy Inspector) Thomas Callahan took over the investigation from the FIAU.

Unlike IAD, Friedland was not satisfied in treating this robbery as a discreet and isolated incident as IAD was to do. He suspected that the R&T Grocery Store robbery indicated wider and deeper problems of corruption within the 75th Precinct. On July 11, 1988, he directed that the FIAU initiate a self-generated investigation into corruption within the entire 75th Precinct and assigned Sergeant Trimboli to undertake that investigation. Thus began Trimboli's years of frustrated attempts to apprehend Michael Dowd and his accomplices.

Friedland had good reason to suspect extensive corruption within the 75th Precinct. Since Dowd returned from the Coney Island detail in 1986, he and his partners, such as Walter Yurkiw, Jeffrey Guzzo, and Kenneth Eurell, regularly engaged in corruption and crimes both on and off duty. By the Summer of 1987, Dowd and Eurell were on the payroll of a major drug organization, taking $8,000 a week in return for providing protection, information, and assistance. Off duty, Dowd, Yurkiw, Guzzo, and Guevara, with the aid of drug dealer accomplices, were committing armed robberies of drug locations in East New York, and Dowd and Eurell were selling cocaine in Suffolk County. By the Fall of 1987, only a year after the 77th Precinct scandal should have taught the Department a lasting lesson, Dowd was driving a new red Corvette sports car into the precinct every day, wearing expensive clothes, throwing lavish parties for friends, and taking limousines from the precinct on gambling jaunts to Atlantic City.

According to Dowd, he did not conceal his well-heeled lifestyle from fellow officers and supervisors, and not one of them ever confronted him to explain what were obvious indications of corruption. In fact, Dowd contends, the opposite was true. Some officers wanted to join him in making scores, and supervisors were content to avoid him rather than challenge him. Dowd knew his supervisors were not naive. Thus, their complacency not only failed to deter his criminal conduct but actually encouraged it.

As early as 1987, IAD's commanders must also have known that Dowd and other officers of the 75th Precinct were engaged in serious crimes. From November 1987 to January 1988, when Dowd and Eurell were at the depths of their corrupt activities, IAD received eight separate allegations involving Dowd, Eurell, and other officers of the 75th Precinct. By the end of 1988, Dowd alone had nine separate allegations of corruption lodged against him at IAD. By the end of 1991, IAD received four more corruption charges against Dowd.

Despite the incontrovertible indications of serious corruption on the part of Dowd and other officers of the 75th Precinct, IAD's commanders over six years, Chiefs Daniel Sullivan, John Moran, and Robert Beatty, never initiated a single investigation of Dowd, until they learned of Dowd's impending arrest by Suffolk County law enforcement officers. They never directed that a single integrity test be attempted; they never placed an undercover in the precinct; they never sought information from the Department's vaunted field associates; they never sought information from the Department's narcotics units. Instead, they directed that each one of the corruption complaints against Dowd and others be assigned as separate corruption cases to the overworked and unequipped PBBN /FIAU, where they became the responsibility of the borough commander and where these cases inevitably died a natural death. In the course of six years, IAD assigned to the PBBN/FIAU no less than twelve separate corruption cases involving Dowd. Every one of them was finally closed as unsubstantiated, and most of those case closings were approved by Brooklyn North's borough commander, Thomas Gallagher, and IAD's commanding officer, Robert Beatty.

What makes matters worse, the corruption complaints received by IAD over the years represented only a small part of IAD's knowledge about Dowd and other corrupt 75th Precinct police officers -- the investigation of the R&T Grocery Store robbery told much more.

Corruption in the 75th PrecinctAfter Yurkiw's arrest on July 1, 1988, IAD's Captain Thomas Callahan, Sergeant (now lieutenant) William Bradley, and other IAD officers of Complaint Investigation Unit 1 ("CIU 1") commenced their attempts to identify Yurkiw's accomplices. By this time, IAD was working the robbery investigation with attorneys of the Office of the State Special Prosecutor ("OSSP"). At every turn, they learned new information about Dowd.

On July 7, 1988, three weeks after the robbery, the 75th Precinct's commanding officer, Deputy Inspector John Harkins, informed Callahan that precinct rumor connected Dowd to the robbery. On July 11, 1988, Lieutenant Richard Armstrong, the precinct's Integrity Control Officer, told IAD investigators about Bailey's Bar, a hangout for Dowd and his crew. Armstrong told Callahan and his investigators that he had information that just before the time of the robbery Dowd was inside Bailey's Bar with Yurkiw, Guzzo, Guevara, and another 75th Precinct Officer, Kimberly Welles.

On July 28, 1988, just three weeks after the robbery, Bradley and OSSP attorney Daniel Landes interviewed two informants who were cooperating with the United States Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of New York. [5] These informants, like Dowd, worked for the Adam Diaz drug gang. They told Bradley and Landes that their drug organization paid Dowd $3,000 to $4,000 and an ounce of cocaine each week in return for police protection. One of the informants even picked out Dowd's and Guevara's photographs from photo arrays.

Officer Took Drug Payoffs, U.S. Charges

By CRAIG WOLFF

Published: July 31, 1992

NEW YORK TIMES

Michael Dowd, the former New York City police officer whose arrest on cocaine trafficking charges spurred four separate investigations of corruption in the New York City Police Department, was arrested yesterday on Federal charges that he received huge weekly cash payments from drug gangs over a three-year period. In exchange, prosecutors said, he provided the gangs with protection against police raids as well as with stashes of guns and police badges.

Mr. Dowd was arrested in May by the Suffolk County police along with four other active officers and one retired officer on charges that they bought and sold cocaine, sometimes through their beats in Brooklyn. Mr. Dowd was arrested again yesterday at his home on Long Island following an investigation by United States Attorney Otto G. Obermaier. He had been out on bail and was dismissed from the department earlier this month.

Integral Part of Drug World

Although there had previously been suspicions and allegations that Mr. Dowd might be cooperating with drug gangs, his arrest yesterday represents the first time he was charged with actually assisting and protecting drug dealers. While Mr. Dowd and the five other officers had been considered rogue officers operating almost as private entrepreneurs, the new charges paint a broader picture of an officer who was an integral part of the drug world. Prosecutors also said informants had told them that other officers had also been receiving payoffs.

With the Police Department already under fire for its failure to detect and root out Mr. Dowd, who has been labeled by law enforcement officials as the mastermind among the arrested officers, the new charges are likely to raise yet more questions about the department's own internal safeguards against corruption.

It also raises questions about why Federal authorities did not decide to prosecute Mr. Dowd sooner. While their investigation began in earnest following Mr. Dowd's arrest, much of the evidence against him was learned by the United States Attorney's office as far back as 1988, when Mr. Dowd was an officer at the 75th Precinct in the East New York section of Brooklyn. He was later transferred to the 94th Precinct in Greenpoint, where prosecutors said he embarked on another drug scheme.

The Dowd case has come to symbolize the new focus on police corruption. In addition to the Federal investigation, Mayor David N. Dinkins appointed a special commission to investigate corruption, the first panel of its kind in New York City in 20 years. Brooklyn District Attorney Charles J. Hynes is investigating the case, and Police Commissioner Lee P. Brown, who has been conducting his own inquiry, has ordered changes in tactics used by the department's Internal Affairs Division.

U.S. Names a Middleman

Federal prosecutors said that they also arrested another man yesterday, Borrent Perez, whom they labeled as a middleman in the payment of money to Mr. Dowd. Mr. Perez was not named or implicated in the previous charges against Mr. Dowd.

The prosecutors said that much of the evidence against Mr. Dowd in the Federal case was learned through members of a Dominican drug gang known as the Company, who were arrested in March 1991, in addition to information learned through members of other drug gangs who said they did business with Mr. Dowd.

One of the gang members told investigators that Mr. Dowd was paid between $5,000 and $10,000 in an envelope that he picked up from Mr. Perez at Auto Sound City, an automobile stereo store on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. The informant told investigators that Mr. Dowd provided advance warning on drug raids.

Shown a picture of Mr. Dowd in 1991, long before the arrest of Mr. Dowd, the informant identified him as "Michael," the officer whom he believed was getting money from Mr. Perez. Prosecutors said the informant was also able to identify Mr. Dowd's partner at the time, whom he said often accompanied Mr. Dowd to the stereo store.

Another member of the Company said that Mr. Dowd provided guns and badges and police radios to the gang. He also identified a photograph of Mr. Dowd in 1991 and said he was known as "Mike the cop."

Prosecutors said that members of another major gang, whose head, Adam Diaz, has been convicted for drug conspiracy, told them that Mr. Dowd also worked with Mr. Diaz's gang. One informant told investigators that Mr. Dowd "regularly received several thousand dollars" at a bodega run by Mr. Diaz at 2788 Atlantic Avenue in East New York, where other officers from the 75th Precinct also received payoffs.

And, prosecutors said, another member of Mr. Diaz's gang paid Mr. Dowd $4,000 weekly from the bodega. This gang member told investigators Mr. Dowd would signal an associate of Mr. Diaz's with a beeper that Federal agents were in the area and that they should stop dealing drugs for the moment. At some point, prosecutors said, Mr. Dowd was supplied with an ounce of cocaine a week by Mr. Diaz.

Asked why Mr. Dowd was not arrested earlier on Federal charges and why Mr. Dowd's partner was not also arrested, assistant United States Attorney David B. Fein said that he was not permitted to comment. Calls to Mr. Obermaier were not returned.

Mr. Dowd's attorney, Marvin Hirsch, said that given recent newspaper articles about Mr. Dowd's possible involvement with drug gangs, he was "not shocked" by the new charges.

But he said he was already thinking about a classic defense, designed to attack the credibility of the witnesses.

"I don't know who it is who is testifying against him," Mr. Hirsch said. "We could have a couple of guys who are in jail, doing 800 years to life, that are looking to better their situation. I'm curious to see how the Government intends to corroborate the statements of these kinds of people."

________________________________________

Arrests in New York Are Said to Cripple A Huge Drug Gang

By SETH FAISON

Published: September 9, 1994

The New York Times

Arsenio Diaz began his career in the drug business in Washington Heights as a corner lookout for a dealer after arriving from the Dominican Republic in 1984, according to law-enforcement officials. Ten years later, they say, he had become the biggest drug dealer in upper Manhattan, and one of the biggest in New York City.

Mr. Diaz, 37, was indicted yesterday, along with 63 of his employees, on murder, conspiracy and drug charges, prosecutors said. Officials said it brought an end to an efficient, $1 million-a-week operation that Mr. Diaz had named, simply, La Compania: The Company.

In a series of raids that began on Tuesday night, the police have arrested 36 Compania members so far. An additional six suspects, including Mr. Diaz, were already in custody. District Attorney Robert M. Morgenthau of Manhattan said this was the second largest drug case ever brought by his office, surpassed by only the so-called French Connection-2 case last year, when 66 were charged.

The arrests, the culmination of a 16-month undercover operation, effectively dismantled the group, Mr. Morgenthau said. With 150 employees, working in two 12-hour shifts, La Compania packaged and sold both powdered and crack cocaine, and used violence and sophisticated electronics to protect its operations in six buildings near Amsterdam Avenue and 150th Street, he said.

That area falls within the 30th Precinct, where 14 police officers were arrested earlier this year in a major corruption scandal. The officers are charged with robbing and beating up drug dealers and with demanding protection money.

Police Commissioner William J. Bratton and Mr. Morgenthau said the possibility of a connection between La Compania and the rogue police officers in the 30th Precinct was under investigation. He would not comment further.

It was a coincidence, Mr. Morgenthau added, that a drug gang linked to Officer Michael Dowd -- whose arrest in 1992 sparked a wide inquiry into police corruption -- was also called La Compania and, sometimes, the Diaz Connection. In that case, the gang leader was believed to be Adam Diaz, who was based in the East New York section of Brooklyn, Mr. Morgenthau said.

At a news conference yesterday, Mr. Bratton appealed to residents of Harlem and Washington Heights, many of whom have expressed anger at the proliferation of drug activity hand-in-hand with corruption in the 30th Precinct, to view the Diaz case as a sign of more aggressive policing.

As with other prominent Manhattan drug gangs that have been knocked down in recent years -- the Jheri Curls, the Wild Cowboys and, most recently, the Young Talented Children -- law-enforcement officials proclaimed a victory in the war on drugs but could not say that it would affect the price or availability of drugs on the street.

Mr. Diaz's lawyer, Oswaldo Gonzales, could not be reached for comment yesterday.

A Complex System

La Compania, prosecutors said, used a complex system to avoid detection by the police. Working in two 12-hour shifts, lookouts used intercoms and cellular telephones to watch for the police, while sellers had remote-control devices to operate electronically controlled trap doors and removable wall panels to hide drugs whenever the police neared.

Walter Arsenault, chief of the Manhattan District Attorney's homicide investigation unit, said police officers with search warrants broke into buildings used by La Compania on numerous occasions, only to find them empty.

Mr. Diaz himself rarely carried drugs, Mr. Arsenault said. His arrest, in June, was something of a fluke.

An Alarm Sounded

A police sergeant and a detective were apparently spotted by Mr. Diaz's lookouts as they neared one of La Compania's buildings, Mr. Arsenault said. At the time, undercover officers from a separate police unit were inside an apartment in the building, trying to make an undercover cocaine purchase, but when an alarm was sounded, they fled with La Compania employees.

The sergeant and the detective found the apartment open and empty, but the door accidentally shut, locking them in, Mr. Arsenault said. Then someone unlocked the door from the outside, he said, and in walked Mr. Diaz with Alejandro Velez, also indicted yesterday, who officials said managed the building.

The officers arrested Mr. Diaz for drug possession after finding an eighth of an ounce of cocaine in the apartment, Mr. Arsenault said.

'We Got Lucky'

"He got sloppy on one occasion," Mr. Arsenault said. "And we got lucky."

Mr. Arsenault said undercover officers collected evidence in 25 separate cocaine purchases from La Compania, beginning in March. Mr. Diaz was held without bail after his arrest, but it took prosecutors three more months to complete the investigation needed to prepare indictments for all 64 suspects.

Mr. Diaz was charged with killing two former members of La Compania and another man at 147th Street and Amsterdam Avenue who were believed to be competing for La Compania's customers.

Mr. Diaz became known to law-enforcement officials as a suspected narcotics dealer shortly before 1990, Mr. Arsenault said, but kept his private life well guarded.

An Illegal Immigrant

Mr. Diaz, an illegal immigrant who arrived from the Dominican Republic in 1984, never applied for permanent-resident status in the United States, prosecutors said.

When he began earning money in the late 1980's, prosecutors said, Mr. Diaz bought a bodega and a beauty salon in Manhattan that operated as legitimate businesses.

After assuming control of La Compania by 1990, he sold the businesses and invested in property in his Dominican hometown, San Francisco de Marcois, which is known for producing talented major-league baseball players.

Mr. Diaz owns a high-price supper club, a disco and several other businesses in San Francisco de Marcois, Mr. Arsenault said, adding that Mr. Diaz could have moved money there so that United States law-enforcement officials would have difficulty seizing it.

'Known as the Mayor'

Mr. Morgenthau said Mr. Diaz's big-spending ways had made him a celebrity in his hometown, where he has spent most of his time since 1990.

"He's known as the mayor," Mr. Morgenthau said.

Mr. Morgenthau also said Mr. Diaz was a celebrity in upper Manhattan, and was widely known as the No. 1 drug dealer there.

Several residents interviewed near Amsterdam Avenue and 150th Street said the brutality and vindictiveness of drug gangs made them reluctant to discuss the gangs. Yet some acknowledged having heard of Mr. Diaz, and more than one expressed surprise at the arrests.

"This is the best thing they've done in all these years," said an elderly woman walking down Amsterdam Avenue. "If they didn't have all this corruption, then maybe it would have been sooner."

Map shows the locations of six La Compania buildings.

As procedure dictated, Bradley recorded this information on work sheets and relayed it to Callahan, CIU 1's commander, and up IAD's chain of command to Inspector Michael Pietrunti, the chief of IAD's Investigations Section, Deputy Chief William Carney, IAD's Executive Officer, and ultimately to IAD's commanding officer, Assistant Chief Moran. Although this information corroborated a number of corruption complaints about Dowd that IAD had received just months before, IAD did nothing with this crucial information other than to pass it on to Sergeant Trimboli -- six weeks later. IAD made no attempt to use this information to expand their robbery investigation to include Dowd. In fact, by Callahan's own admission, by August 1988, Dowd was not a target of IAD's investigation.

If Callahan and his superiors believed that all this information was not enough to justify a full-scale IAD investigation into Dowd and drug corruption in the 75th Precinct, even more information was to come.

On August 29, 1988, detectives of the 62nd Precinct arrested Yurkiw (who was out on bail on the robbery charges) for harassing his former girlfriend. After his arrest, Detective Gerard Wiser overheard Yurkiw on the precinct telephone stating: "If this [his arrest] isn't handled right, he would call Hynes's Office [the OSSP] and blow the whistle." Detective Wiser passed on this information to Bradley. Although no one at IAD bothered to check, Yurkiw's telephone call was to Michael Dowd. Yurkiw was attempting to pressure Dowd into coercing his girlfriend to drop the harassment charges. No one at IAD, moreover, ever asked Yurkiw what information he possessed about which he could "blow the whistle." In fact, attempting to turn Yurkiw or any of his accomplices (with the cooperation of the OSSP, of course) was not an investigative tactic ever attempted by IAD.

The next day, Bradley interviewed Yurkiw's girlfriend, an admitted cocaine user. She told Bradley that she knew Yurkiw was a corrupt cop. She told him that on a number of occasions, she had seen him in his apartment with Dowd, Guzzo, and Guevara in possession of large quantities of cocaine and money laid out on the kitchen table. IAD did nothing with this information other than record it in a worksheet and pass it on to the OSSP.

But that was not the end of Yurkiw's girlfriend's information. Three months later, on November 30, 1988, IAD arrested Yurkiw again on her complaint that Yurkiw had threatened her life to force her to act as an alibi witness for him at his robbery trial.

From November 30 to December 1, 1988, Sergeant Bradley interviewed Yurkiw's girlfriend four times. Her information confirmed that the 75th Precinct was in the throws of rampant drug corruption. She gave Bradley specific information. She reported that Yurkiw told her that there was a group of approximately twenty-five police officers in the 75th Precinct who were systematically robbing drug dealers and drug locations. She told Bradley that before the July 1988 robbery of the R&T Grocery Store at 923 Livonia Avenue, she had observed that address and others on a list of known drug locations in East New York that Yurkiw kept in the glove compartment of his car. She told Bradley that these robberies were taking place since February 1987 and that Yurkiw transported cocaine from drug locations in the 75th Precinct to Suffolk County for Michael Dowd and his brother, who was also a police officer.

When questioned by Commission investigators, Yurkiw's girlfriend stated that based on her conversations with Yurkiw and her observations of his activities with Dowd and other police officers, she knew that the 75th Precinct suffered a corruption problem of large dimensions. She said that she could tell that IAD investigators did not believe her. She was right. In his report of his November interviews with her, Bradley added a personal assessment of her credibility. In essence, Bradley stated that because she was an admitted drug user and had a romantic entanglement with Yurkiw, her "credibility and allegiances were suspect" (See Exhibit B). It is very curious, however, that her allegations and credibility were sufficient to constitute the basis of two additional arrests of Yurkiw in August and November 1988.

According to Bradley, he forwarded all of this information to his superiors: Callahan, Pietrunti, Carney, and Moran. Not one of them ever directed that IAD explore Yurkiw's girlfriend's allegations in any way. In fact, IAD never even assigned her information a corruption case number, as procedure dictates for every corruption allegation that comes to IAD's attention. Her information indicating large-scale corruption in the 75th Precinct was, in a word, buried.

On December 27, 1988, IAD's investigation of the R&T Grocery Store robbery was closed with a final report written by Bradley and Callahan, endorsed by Chief Moran and addressed to Chief Sullivan. Despite all the evidence IAD had obtained about his corrupt activities, the final report makes not a single mention of Michael Dowd. No one at IAD ever initiated a single investigation of Dowd or any other police officer of the 75th Precinct despite the extensive evidence.

Incredibly, neither Callahan, Bradley, nor any other IAD investigator communicated this vital information to Sergeant Trimboli, who, by this time, was conducting a one-man, precinct-wide investigation into corruption in the 75th Precinct. It was only in October 1989, when Trimboli was finally allowed to review IAD's case files, that he learned about Yurkiw's girlfriend's information, Yurkiw's telephone conversation overheard by Detective Wiser, and the fact that at the time of his sentencing Guzzo offered to provide information to IAD about other corrupt cops in the 75th Precinct -- all critical information that IAD had in its possession for months, never put to any use, and never told to Sergeant Trimboli.

The Trimboli InvestigationAt the same time IAD was investigating the R&T Grocery Store robbery with a team of seven investigators, including two sergeants, two lieutenants, and a captain, Sergeant Trimboli alone was conducting the investigation that IAD should have undertaken: the investigation of potentially widespread corruption within the 75th Precinct. When questioned by former Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly and later by Commission investigators about IAD's startling lack of action against Dowd during the R&T Grocery Store investigation, Callahan stated that he thought PBBN/FIAU was "hot on the trail of Michael Dowd." But Callahan and his superiors had reason to know otherwise.

When Trimboli launched the PBBN /FIAU's self-generated case (corruption case no. 88-966) in July 1988, IAD's Chief Moran or his executive officer, Chief Carney, ordered a "monitor" of the investigation, a relatively rare practice for IAD. The monitor required Trimboli to submit his worksheets to IAD on a weekly basis, allowing them to watch Trimboli's progress closely and keep a contemporaneous account of his investigation's developments. Placing a monitor on the case told Trimboli that, for better or for worse, IAD's commanders had a special interest in the progress of his investigation.

By the Fall of 1988, when IAD had already ruled out Dowd as a subject of their robbery investigation, Trimboli had acquired enough information to know that the 75th Precinct's corruption problems went far beyond even Michael Dowd. And, through its monitor of the case, so did IAD.

Two months into Trimboli's investigation, in September 1988, 75th Precinct detectives arrested Jorge Royos, [6] a drug dealer with connections to East New York drug traffickers Adam Diaz and Baron Perez. After his arrest, Royos, wanting to make a deal, told detectives he often socialized with police officers, including Michael Dowd, his brother, Guzzo, Guevara, and Kenneth Eurell. He informed the detectives that the Dowds used cocaine and associated with drug dealers at Auto Sound City, an East New York car stereo store. Trimboli knew that Auto Sound City was connected to Dowd. On two separate occasions Trimboli observed Dowd's red Corvette parked inside the location. On the second occasion, Trimboli actually had a conversation with Perez who admitted that he knew Dowd and that various cops from the 75th Precinct visited Auto Sound City.

While in jail awaiting trial, Royos telephoned Trimboli in October 1988, about a month after their first meeting. He told Trimboli that he was willing to give him more information about "the man with the red Corvette." After notifying IAD of the offer, Trimboli interviewed him.

Royos confirmed what Trimboli had already strongly suspected. Auto Sound City was a front for a large drug organization and was used as a center for the delivery and distribution of cocaine and the transportation of guns. He told Trimboli that someone named Adam (Adam Diaz) ran the operation and paid off Dowd for police protection and for special deliveries of cocaine in amounts of five kilograms or more. He told Trimboli that Yurkiw, Guzzo, and Guevara committed armed robberies of drug locations where Dowd informed them drugs had been delivered. He also told Trimboli that Eurell was a heavy drug user. Royos agreed to view photo arrays and assist Trimboli's investigation.

With Royos's help, Trimboli's investigation now showed promise of apprehending 75th Precinct officers who were involved in serious narcotics corruption. But he knew he could not do it alone. A case of such magnitude, he believed, required IAD's assistance and expertise. He also knew that at that very time, IAD's Captain Callahan was investigating the armed robbery of the R&T Grocery Store committed by Yurkiw, Guzzo, and Guevara, three of the 75th Precinct Police Officers Royos identified.

The day after he interviewed Royos, Trimboli telephoned IAD. He spoke to lieutenant Hotaling of IAD's Staff Supervisory Unit, briefed him on Royos's information, and requested IAD's participation and assistance. Hotaling, sensing that the case had reached a critical juncture, told Trimboli that he would consult Callahan.

When questioned by Commission investigators, Hotaling stated that in the Fall of 1988, the R&T Grocery Store robbery investigation was the most significant police corruption case IAD was conducting at that time. According to his testimony, IAD investigators and their superiors were well aware of the dimension of the corruption problems in the 75th Precinct, Dowd's central role in that corruption, and Trimboli's investigation. On occasion, he would inform Callahan of Trimboli's developments in an effort to persuade Callahan to expand his investigation to include Dowd and other 75th Precinct officers. Hotaling described Callahan's reaction to his attempts in a private hearing:

Question: Were you bringing Callahan the worksheets [of Trimboli's investigation]?

Hotaling: Oh yeah, I was bringing them to him let's say for the first three or four months. Captain Callahan wasn't thrilled with the fact that I was bringing him [Trimboli's] worksheets.

Question: What do you mean?

Hotaling: ... [I]t got to the point when he said to me one time -- I brought a worksheet to him -- and I said, 'Captain, I got a worksheet on Dowd.' And he got very upset and he said, 'What are you bringing this here for?' [I said,] 'I'm doing a monitor on it and its relevant to the 75 [precinct] and the case you are doing.' Then I was told by him, 'What does this have to do with my case? ... I don't know why you are bringing this. It has nothing to do with my case, so don't bring it to me.' So I didn't bring them [Trimboli's worksheets] to him anymore ....

Question: So you were basically told by Captain Callahan not to give him information on Dowd?

Hotaling: ... I wrote it off to the fact that Callahan ... didn't want more work and what I was bringing to him might broaden his investigation; you know, it was the old 'kill the messenger' syndrome.

Just hours after Trimboli's conversation with Hotaling about Royos's information, Sergeant Robert Rockiki, Hotaling's subordinate, telephoned Trimboli and informed him that Callahan declined to become involved with Trimboli's case and that Trimboli should continue with his own investigation. In response to IAD's refusal to assist Trimboli, the FIAU's commanding officer, Captain Friedland, telephoned IAD to reiterate the request for assistance. He was told by Captain (now Deputy Inspector) Martin Johnson, the commanding officer of the Staff Supervisory Unit, that IAD would provide no assistance and that the FIAU was free to contact any outside agency for assistance. Thereafter, Trimboli informed attorneys of the OSSP about the developments in his case.

In essence, Johnson's message was clear: IAD, the Department's central anticorruption division, refused to assist an investigation of potential large-scale corruption; that if the FIAU needed help, it could turn to any agency but the one it was supposed to. This would not be the last time IAD refused Trimboli's pleas for help.

As Trimboli's investigation continued in November 1988, yet another informant [7] surfaced who had information on police corruption in the 75th Precinct. In jail on charges of burglary, this informant told PBBN /FIAU's Sergeant Kenneth Carlson that several officers of the 75th Precinct regularly bought and sold narcotics. His information corroborated what Royos had told Trimboli. He told Carlson (who debriefed the informant in Trimboli's absence) that he knew of seven officers, including Dowd, who were engaged in narcotics trafficking and was able to identify three of the officers from photo arrays. As Royos told Trimboli, this informant told Carlson that the officer who "drives the red Corvette" (Dowd) is a "runner" for a drug organization and makes deliveries of narcotics out of Auto Sound City. Also consistent with Royos's information, he told Carlson that Dowd set up the robbery of the R&T Grocery Store in July.

Even in the face of this corroborating information, IAD still failed to initiate a case against Dowd or other officers in the precinct. In fact, this information came less than four weeks before Yurkiw's girlfriend informed IAD's Sergeant Bradley of extensive drug corruption in the 75th Precinct. Yet, despite this mounting information, IAD's commanders, Moran, Carney, Pietrunti, and Callahan -- as they had done in the past -- treated these new allegations as a separate and unrelated case, gave it a new corruption case number, and assigned the investigation to the PBBN /FIAU.

Of course, when Trimboli received these new allegations he knew his case was expanding rapidly. According to Trimboli, by the end of November 1988, he already had fifteen to twenty 75th Precinct officers as subjects of his investigation. And IAD knew it. They continued to receive his worksheets on a weekly basis and continued to refuse to offer any assistance.

But Trimboli was not through asking for help. In late November 1988, the commanding officer of the Whitestone Pound, where Dowd had been assigned since August after his release from an alcohol rehabilitation clinic, notified Trimboli that he observed Walter Yurkiw at the Pound. To Trimboli and Friedland, Yurkiw's presence at the Pound where his car was being held as evidence in the grocery store robbery, confirmed Dowd's continuing association with corrupt cops despite his transfer out of the 75th Precinct.

In light of this event and the rapidly accumulating information about Dowd and others, Trimboli and Friedland met with their borough commander, Assistant Chief Thomas Gallagher, to inform him of the developments in Trimboli's investigation. According to Trimboli, Friedland, and the records in Trimboli's case file, Gallagher ordered Friedland to arrange a meeting for him with IAD's commanders to discuss a joint investigation into the 75th Precinct. When questioned by Commission investigators, however, Gallagher testified he had no recollection of ever requesting such a meeting.

Despite Gallagher's lack of memory, Trimboli's worksheets show that on November 21, 1988, Friedland telephoned Captain Johnson and Captain Joseph Nakovics of IAD to communicate the request, on behalf of Chief Gallagher, for a meeting with IAD's commanding officer, Chief Moran, to discuss the FIAU's need for personnel and equipment to assist Trimboli's investigation. Nakovics returned Friedland's call and told him that IAD would not offer any assistance to the FIAU, that there was no personnel or equipment to spare, and that a meeting at IAD was not necessary.

Trimboli was dumbfounded. He could not believe that IAD would abruptly refuse a borough commander's request for a meeting on an important case of police corruption. This was the second occasion that IAD refused the FIAU's direct appeal for assistance. From then on, Trimboli knew that if he was ever to apprehend Michael Dowd, he would have to do it alone. In his view, IAD's inexplicable behavior could only be explained in one way: IAD simply did not want his investigation to succeed; or as he testified at the public bearings, "they did not want it to exist."

Of course, although IAD told the FIAU to go away, information about Dowd simply would not go away. In December 1988, Trimboli and OSSP attorneys debriefed Royos again and he gave even more details of his involvement with Dowd, Yurkiw, and other officers. Most significantly, he stated that he was involved with Yurkiw, Guzzo, Guevara, and Dowd, in a number of armed robberies of drug locations. He stated that he set up the first of several stickups at the R&T Grocery Store by tipping off Yurkiw when narcotics would be on the premises. He stated that Yurkiw, Guzzo, and Guevara robbed the place on a number of occasions, culminating with their arrests in July 1988. He told Trimboli and OSSP attorneys Dennis Hawkins and Daniel Landes that after the robberies, they would meet at Bailey's Bar to divide the proceeds, ranging from a half pound to a full pound of cocaine. At least ten police officers, including Michael Dowd, his brother, and Kenneth Eurell used and divided the drugs. Royos also indicated that Adam Diaz, the boss of the drug organization connected to Auto Sound City, rented his father's grocery store on Blake Avenue in East New York and used it as drug sale spot. During that time, Dowd and Eurell were in the store on a regular basis to collect their payoffs from Diaz. Trimboli passed on this information to IAD through its monitor of his case. Although Royos's latest information surfaced before CIU 1 closed its robbery investigation of the very same officers Royos identified, IAD still did not expand its robbery investigation to include these growing allegations.

Within a month, Trimboli got more news about Dowd. In late January 1989, he discovered that Dowd and a police officer, who was still assigned to the 75th Precinct, were taking a trip to the Dominican Republic, Adam's home country. The trip confirmed that Dowd continued his association with 75th Precinct officers who were subjects of Trimboli's investigation and made him suspect that Dowd might be delivering drugs for Adam across international borders. On his own initiative, Trimboli made arrangements with the Drug Enforcement Administration to keep track of Dowd's activities while in the Dominican Republic. Upon their return to New York, an FIAU investigator observed Walter Yurkiw at the airport to meet Dowd confirming their continuing association. This information was also delivered to IAD.

The Pro-Active PlanDuring February 1989, Trimboli and the OSSP made plans to release Royos from prison so that he could make a drug buy from Diaz in an attempt to turn him against Dowd, Eurell, and any other officers involved with Adam's drug ring. Once the OSSP finalized the arrangements with Royos and his attorney, Friedland notified IAD. This time IAD consented to a meeting.

Trimboli was suspicious. For the past ten months of his investigation, IAD had done nothing but throw roadblocks across his path. Now that, despite the odds, his investigation had achieved the prospect of infiltrating the drug ring at the center of police corruption in the 75th Precinct, IAD wanted to be consulted. As he told Commission investigators, Royos's cooperation was the most promising development of his investigation. But he was not sure whether IAD really wanted to help or simply wanted to keep an eye on what might be the beginning of another police corruption scandal. On March 9, 1989, Friedland and Trimboli attended a meeting at IAD, represented by Deputy Chief Carney, Deputy Inspector Pietrunti, Captain Johnson, and Captain Callahan. Although recollections differ greatly about the discussion at this meeting, it apparently involved obtaining IAD's approval for the planned use of Royos as an operative in Trimboli's investigation. Curiously, neither Moran nor Sullivan attended the meeting -- although they were the only two in IAD's strict command structure with the authority to approve such an operation.

The results of the meeting, however, are clear. IAD refused to take any responsibility for removing Royos from prison to participate in the operation. According to Friedland, Moran had serious misgivings about removing Royos from prison for an operation with a "remote chance of success." Moran insisted that if Royos were used, OSSP would have to take full responsibility for Royos and the operation, and Trimboli was prohibited -- either on his own account or on behalf of the OSSP -- from signing Royos out of prison. According to Friedland's recollection, Captain Johnson stated that if these conditions were met, IAD would provide an undercover officer for the operation.

In Trimboli's view, IAD's response to the Royos plan was another attempt to impede his investigation at its most critical juncture. Since his investigation had finally produced a potentially productive opportunity, IAD's commanders were in no position to disapprove it outright. Instead, they imposed difficult conditions of approval they thought could not be met.

To Trimboli, Johnson's conditional offer of an undercover officer was also suspect, since only Moran or Sullivan had the authority to authorize it, and neither of them even attended the meeting or ever communicated their approval of the plan to Friedland or Gallagher. Trimboli's view has merit. During interviews with Commission investigators, neither Chief Moran nor Chief Sullivan recalled being consulted on a plan to use Royos, let alone approving the use of an IAD undercover.

In response to IAD's conditions, the OSSP agreed to accept full responsibility for Royos and the operation. But before Royos ever hit the street, Trimboli ran into another roadblock. But this time it came not from IAD, but from his own borough commander.