In 1903 an International Buddhist Society had been founded, following the period spent in the East by Allan Bennett, alias the "Bikkhu Ananda Metteya," who had passed into Buddhism from the magical activities of the Golden Dawn. An English Buddhist Society was formed in 1907, but by 1924 the chief association for the dissemination of Buddhist doctrine in England was the Buddhist Lodge of the Theosophical Society, founded by the eminent lawyer and judge Christmas Humphreys. In 1936 Alan Watts took over the editorship of the Buddhist Lodge's magazine, Buddhism in England, at the age of sixteen, and the same year, he published his Spirit of Zen. The father of this prodigy, L. W. Watts, was the treasurer and vice-president of the Buddhist Lodge; [30. Christmas Humphreys, Sixty Years of Buddhism in England (London, 1968), pp. 20-40. Other heroes of Kerouac -- for example, Dwight Godard, compiler of A Buddhist Bible, published in the United States in 1928 -- are also the heroes of the European Buddhists.] and Alan Watts also sat at the feet of Dmitrije Mitrinovic. In 1938 the younger Watts left for the United States and became a doctor of theology and an Anglican counselor at Northwestern University. Then he moved to San Francisco from where his influence spread first throughout the Beatnik, then throughout the hippie world. As has been rightly pointed out, [31. Theodore Roszack, The Making of a Counter-Culture (London, 1970), p. 132.] it is more the influence of Watts than the more learned message of the leading Zen authority for the West, D. T. Suzuki -- whose second wife was American -- that has been responsible for spreading Zen ideas. Watts by no means confined himself to Zen and was himself the modern representative of those "mediators between East and West" who first became prominent in Europe and America in the middle of the last century. [32. An additional factor in spreading consciousness of Zen in America was undoubtedly the occupation of Japan. After 1945 there was a great increase in East Asian studies, and it is interesting that Zen properly entered England after the Second World War, when Christmas Humphreys -- who had been sent as a counsel to the War Crimes Trials in Tokyo -- visited Suzuki. It is symptomatic of the close links between the Occult Revival and the coming of Zen to the West that at the time of his trip Humphreys was preparing a new edition of the Mahatma Letters to H. P. Blavatsky, and that his journey included a visit to the headquarters of the Theosophical Society at Adyar near Madras. See Humphreys, Via Tokyo (London, 1948).]

-- The Occult Establishment, by James Webb

The Buddhist Society had been founded in 1924 as the Buddhist Lodge of the Theosophical Society, from which it separated two years later as a result of the Krishnamurti debacle, and members and friends would soon be celebrating its fortieth anniversary. Christmas Humphreys, the President (‘Toby’ to his intimates within the Society), was Britain’s best-known Buddhist and his best-selling Pelican Buddhism had probably introduced more people to the Buddha and his teachings than had any other book since the publication of Sir Edwin Arnold’s The Light of Asia in 1879. Perhaps because of its origins in the Theosophical movement, and Humphreys’ personal sympathies (he believed Buddhism and Theosophy to be complementary), the Buddhist Society’s approach to the Buddha-Dharma was not sectarian but ecumenical. Besides running its own classes and holding the Summer School, it provided a platform for visiting Buddhist teachers of all traditions, and was the central body to which what London-based Buddhists called ‘the provincial groups’ were loosely affiliated. Since the appearance of Dr D.T. Suzuki’s writings in the fifties, Christmas Humphreys’ special interest within the field of Buddhism had been Zen, and his ‘Zen class’ (the scare quotes indicate its admittedly non-traditional status) was in effect the Buddhist Society’s equivalent of the Theosophical Society’s esoteric section. Other members of the society had a special interest in the Theravãda and it was one of these who, as the Bhikkhu Kapilavaddho (formerly William Purfurst), had in 1956 been mainly responsible for forming the [English] Sangha Trust and, I think, the Sangha Association, with the object of creating in Great Britain a monastic community for Westerners.

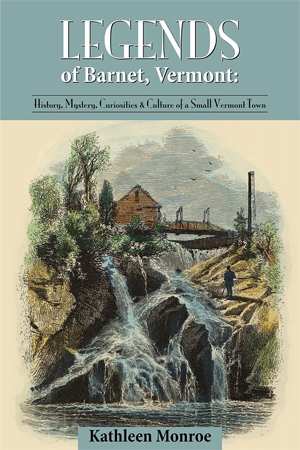

-- Moving Against the Stream: The Birth of a new Buddhist Movement, by Sangharakshita [Dennis Lingwood]

A.C. March, a Founding Member of the Buddhist Society and the creator of its Journal, now The Middle Way.

Buddhist Lodge Monthly Bulletin, edited by A.C. March, 1925-1926

-- Issei Buddhism in the Americas, edited by Duncan Ryuken Williams, Tomoe Moriya

"An Analysis of the Pali Canon" was originally the work of A.C. March, the founder-editor of "Buddhism in England" (from 1943, The Middle Way), the quarterly journal of The Buddhist Lodge (now The Buddhist Society, London). It appeared in the issues for Volume 3 and was later offprinted as a pamphlet. Finally, after extensive revision by I.B. Horner (the late President of the Pali Text Society) and Jack Austin, it appeared as an integral part of "A Buddhist Student's Manual," published in 1956 by The Buddhist Society to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of its founding.

-- An Analysis of the Pali Canon and a Reference Table of Pali Literature, by Russell Webb, Bhikkhu Nyanatusita

A.C. March (1929), "Comment on Ananda Metteya's Article," BE, 4(6), p. 130.

-- Men, Masculinities and Religious Change in Twentieth-Century Britain, edited by L. Delap, S. Morgan

Taixu, then thirty-nine years old, returned to China from the United States in late April 1929, arriving in Shanghai feeling rather optimistic about the future of his program of modernization and reform. He was encouraged by the response that he had received in the West to his plans for a World Buddhist Institute and to his call for greater cooperation among Buddhists around the globe, and obviously pleased that many had recognized him as a religious leader with both a vision for the modern reformation of Buddhism and a realistic plan for carrying it out. A.C. March, of the Buddhist Lodge of London, had concluded, for example, that "Taixu is a very practical man. He is no dreamer.... Now that China has definitely entered the work of establishing Buddhism throughout the world as a universal religion, we may expect great results to follow."

-- Toward a Modern Chinese buddhism: Taixu's Reforms, by Don Alvin Pittman

The same year, Humphreys founded the London Buddhist Lodge, which later changed its name to the Buddhist Society.[1] The impetus for founding the Lodge came from theosophists with whom Humphreys socialised. Both at his home and at the lodge, he played host for eminent spiritual authors such as Nicholas Roerich and Dr Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan, and for prominent Theosophists like Alice Bailey and far Eastern Buddhist authorities like D.T. Suzuki. Other regular visitors in the 1930s were the Russian singer Vladimir Rosing and the young philosopher Alan Watts,[3] and in 1931 Humphreys met the spiritual teacher Meher Baba.[4] The Buddhist Society of London is one of the oldest Buddhist organisations outside Asia.

-- Christmas Humphreys, by Wikipedia

Buddhist Society in England (was the Buddhist lodge of the Theosophical Society), was founded by the most famous and influential of Western Buddhists, Christmas Humphreys (see Christmas Humphreys), who was a member of the Theosophical Society early in his life and who wrote appreciatively about H.P. Blavatsky to the end of his life.

-- Famous People and the impact of the Theosophical Society: Inventory of the influence of the Theosophical Society, by Katinka Hesselink

Resources for Buddhist Lodge (London, England).

Buddhism in England

Buddhist Lodge (London England)

Periodical: 1926-1943

Buddhism and the Buddhist movement to-day: an explanatory booklet compiled for the benefit of enquirers / compiled by the Buddhist Lodge, London

Buddhist Lodge (London, England)

[Book: 1930]

Concentration and meditation: a manual of mind development

Buddhist Lodge (London, England)

[Book: 1935 ]

What is Buddhism? : an answer from the Western point of view / compiled by the Buddhist Lodge, London

Buddhist Lodge (London, England)

[Book: 1929-1931 ]

I heard one of the Warriors of the Lodge say once that he is sick of hearing about the Vidyadhara. Perhaps he was referring to habitual patterns of some students living in the past. Perhaps fifteen years ago, there was a point to making a sharp distinction between the past and present. But that logic no longer serves the situation. It is simply not true that we, as a community, or we, as senior students, are clinging to the Vidyadhara’s memory, instead of living in the present Dharmic norm, generally speaking, although perhaps it does occur. The problem here is not clinging to the past. The problem is competing with it.

-- Keeping Alive the Transmissions of the great Vidyadhara, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, by Bill Karelis

Whoever set up that secret society Lodge business (Rome?) made a HUGE error. Set the whole thing back by decades. .....

-- Baron Ash, from Inside the Tiny Pathetic World of Sakyong Mipham, by allthewholeworld

When I wasn’t with CTR, I was completing my tasks as a nanny. And I was introduced to the Shambhala lodge with a party in my honor.

-- The first time I met His Majesty Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, by Leslie Hays

Scorpion Seal Authorization

This text is restricted to practitioners who have attended a Scorpion Seal Assembly or have been a Shambhala Lodge member prior to 1990. Please state the date and location where you attended SSA1 or received Lodge transmission.

-- Scorpion Seal of the Golden Sun, by Nalanda Translation

In 1975, Shambhala Lodge was founded, by a group of students dedicated to fostering enlightened society.

-- Shambhala Buddhism, by WikiMili

1975: Forms the organization that will become the Shambhala Lodge, a group of students dedicated to fostering enlightened society. Founds the Nalanda Translation Committee for the translation of Buddhist texts from Tibetan and Sanskrit. Establishes Ashoka Credit Union.

-- Chögyam Trungpa, by Wikipedia

The Council of Warriors and its Warrior General Martin Janowitz were empowered by Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche in 1997 with the mission of re-energizing Shambhala’s world-wide commitment to realize enlightened societies in Nova Scotia and beyond and to promote the essential practices of Shambhala. The Halifax Kalapa Shambhala Society was initially formed as the Shambhala Lodge during the epoch of the Druk Sakyong, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. The Society included all Halifax practitioners who had received the authorizations to attend Kalapa Assemblies and to practice the Werma Sadhana and most recently was led by Warriors of the Centre Bob Vogler and Marguerite Drescher. As part of the transition to Shambhala’s current pattern of governance the Council of Warriors, worldwide ‘Lodges’ and Warriors of Centers were retired.

-- Windows!, by halifax.shambhala.org

Acharya Janowitz became a student of the Druk Sakyong (Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche) in 1970. He taught a wide array of programs and co-designed the first teacher training course. He was among a pilot group of Shambhala Training Directors. He traveled widely with the Druk Sakyong for many years and was named Kusung Dapon — senior Kusung (Court Protector) responsible for oversight of the personal guardian attendants of the Mukpo family, the Vajra Regent and his family, and the Kalapa Court. In 1997 he was appointed Warrior General of Shambhala by the Sakyong a position he held until 2010. The Warrior General is responsible for the leadership of the Council of Warriors, Warriors Centres and Kalapa Lodges worldwide. Acharya Janowitz is a member of Shambhala’s Touching the Earth Working Group and has developed Spirituality and Sustainability dharma programs. He was the founding Treasurer of Ashoka Credit Union. He was also founding Executive Director of Naropa Institute (now University) as well as a founding member of the Naropa Board of Trustees. Acharya Janowitz was Chair of the Board from 2000 to 2012. He has worked on numerous environmental sustainability and alternative energy development initiatives and is currently Chair of the Nova Scotia Roundtable on Environment and Sustainable Prosperity. He is also the Chair of The Authentic Leadership in Action Institute, or ALIA (formerly the Shambhala Institute) and Vice President and Practice Leader for Sustainable Development for Stantec Consulting. Stantec focuses on community sustainability, climate change adaptation, corporate social responsibility, sustainable infrastructure and strategic sustainability performance. He is a member of the Halifax Strategic Urban Partnership Core Leadership Group, Envision Nova Scotia Steering Committee, and Buddhist Climate Change Initiative.

-- Acharya Martin Janowitz, by shambhalaonline.org

The following is part of a talk given by the Dorje Dradül to members of the Shambhala Lodge in January of 1979:

“... Also in our kingdom, we might have a percentage of citizens or subjects who might be Christians or Jews in their own right, and of their own faith. And it is necessary for them to take Shambhala Training as we run our country, and beyond that, they will find their own religious conviction of becoming true and good Christians or good Jews, speaking Hebrew perfectly. We should try to institute that particular approach. People of any faith that come along to our kingdom would practice their own discipline. Their theism has no problem if there is any contemplative discipline of their theism.

“So you are not taking this oath just to make people into Buddhists, but you are taking this oath so that you can afford to be beyond Buddhism. That's why we call it Shambhala. The oath water that you are going to drink is the water of greater vision.”

-- Shambhala Guide Resource Manual: A Resource for Directors, Students, and Centre Administrators

*************************

"Buddhism as Theosophy," Excerpt from Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and the Columbian Exposition

by Judith Snodgrass

Buddhism as Theosophy

Olcott had originally accepted the invitation to Ceylon as an opportunity to establish branches of the Theosophical Society. Once he became involved in local issues, however, the promotion of Buddhist reform took priority and he declared that the Theosophical Society in Ceylon would be "devoted to all matters concerning Buddhism and would be the means of spreading Buddhist propaganda."22 The non-Theosophical nature of the society in Ceylon was underlined by the formation of a small and entirely separate "Lanka Theosophical Society composed of Freethinkers and amateurs of occult research."23

Similarly, although the invitation to tour Japan included the inducement of forming Japanese branches of the Theosophical Society, the one local branch of the society created with "Hongwanji officials for officers" was, as even Olcott observed, a mere formality; it "never did any practical work as such."24 By the time of his visit to Japan Olcott had become occupied with the idea of uniting the various Buddhists of the world, creating a united front against Christianity, and a common platform from which to proselytize. This was to be achieved through the Buddhist Division of the Theosophical Society, led by Olcott himself, "for it goes without saying that it can never be effected by any existing organization known as a Buddhistic agency."25 By the end of his first tour of Japan, Olcott was so enthusiastic about the plan that he considered resigning from the Theosophical movement to devote himself entirely to building up "an International Buddhistic League that might send the Dharma like a tidal wave around the world." Nothing eventuated from this idea because it was opposed by both Madame Blavatsky and "a far higher personage than she."26

Olcott's personal ambition for his visit to Japan was to initiate this movement by uniting Southern and Northern Buddhists, and to this end he carried a letter in Sanskrit from Sumangala, representing Theravada Buddhists, to the chief priests of Japanese Buddhism expressing the hope that the Buddhists of Asia would unite for the good of the whole Eastern world.27 As Olcott informed the gathering of the heads of the Eight Buddhist Sects of Japan: "My mission is not to propagate the peculiar doctrines of anyone sect but to unite you in one sacred undertaking."28 While Meiji Buddhist reformers were similarly committed to a united, nonsectarian platform, their goal was a union of Japanese Buddhist sects. Any vision they might have held of union between Mahayana and Theravada Buddhists was not to be achieved by reduction to a lowest common denominator, as Olcott proposed, but by encompassing the Theravada within the ultimate truth of Japanese Mahayana.

Why did Olcott wish to promote Buddhist unity? One reason was that he was opposed to the Christian missionary effort in Asia and believed that only by banding together could Buddhists be strong enough to compete with the Christians and counter the immense strength and wealth of the Christians with their Bible, tract, Sunday school, and missionary societies.29 Another reason was his Theosophical interpretation of Buddhism, which saw the Buddha as one of the Adepts and equated his teaching with Theosophy, the occult science that lay at the root of all true knowledge.30 Olcott's own account of taking Buddhist vows in Ceylon shows that he rejected all existing Buddhist practice: "[T]o be a regular Buddhist is one thing, and to be a debased modern Buddhist sectarian is quite another." He also claimed the greatest possible freedom for personal interpretation: "[ i]f Buddhism contained a single dogma that we were compelled to accept, we would not have taken the pansil nor remained Buddhists ten minutes."31 Olcott's public avowal of "Buddhism" was for him simply a statement of his commitment to Theosophy.32 "Our Buddhism was that of the Master-Adept Gautama Buddha, which was identically the Wisdom Religion of the Aryan Upanishads, and the soul of all the ancient world-faiths."33

Consequently, although Olcott's interpretation of Buddhism, like that of Pali scholars, denied the legitimacy of contemporary Buddhists whose practices he regarded as degenerations from the original teachings of the Master-Adept, it diverged significantly in other respects. It did not privilege Theravada Buddhism over the later Mahayana Buddhism, for it was here that he most readily found the "Mahatmas" and the "siddhis" of Theosophy. He also accepted the doctrine of the succession of Buddhas, the teaching that Sakyamuni was one in a line of Buddhas that are born in this world to revive the perennial dharma. This doctrine, though found in the earliest Pali sutras, was typically dismissed as "priestly elaboration" because it conflicted with the historical view that Buddhism was founded by Sakyamuni. It did, however, conform to the Theosophical account of the Adepts, conveniently providing Madame Blavatsky's "pre-Vedic Buddhism."

Olcott's Buddhist publications borrowed freely from the sources of both Northern and Southern Buddhism to support his Theosophical mission. The Golden Rules of Buddhism (1887) contained a chapter called "Adeptship a Fact" -- an overt appropriation of Buddhism to the cause of Theosophy -- that depended on selected passages from Chinese Buddhist texts.34 These liberties did not go unnoticed. Olcott's first publication on the subject was The Buddhist Catechism (1881), a Buddhist version of those "elementary handbooks so effectively used among Western Christian sects."35 It was intended for use in Buddhist schools and Sunday schools, to protest against and substitute for the Christian Bible tracts used to teach English in Sinhalese schools. The Buddhist Catechism incorporated Buddhist "legitimation" of concepts of Theosophical interest such as auras, hypnotism and mesmerism, the capacity for occult powers, and displays of phenomena.36 Apart from such dubious additions, it was a gross simplification of the doctrine and caused considerable uneasiness among the monks who supervised its production. Olcott commented that it would not have been published if he were Asian, but "knowing something of the bull-dog pertinacity of the Anglo-Saxon character, and holding me in real personal affection, they finally succumbed to my importunity."37 Even with these concessions, an impasse over the definition of nirvana almost aborted the project. Olcott attempted to suggest the "survival of some sort of 'subjective entity' in that state of existence," claiming that this was the view of Northern Buddhists, but "the two erudite critics caught me up at the first glance at the paragraph."38 On this occasion Olcott reluctantly modified his entry. He did nevertheless manage to produce in the Catechism a version of Buddhism that supported and propagated his Theosophical beliefs, and this anecdote-suggesting as it does that the work was produced under the strict supervision of specialists -- claimed authentication for it as an accurate interpretation of Buddhism.

Although the Catechism served its immediate political purpose and survived through multiple editions in several languages, Olcott's erstwhile patron Mohottivatte began composing his own catechism in 1887, explaining specifically the need to reassert the true doctrines of Buddhism against the false teachings many Western sympathizers had begun to incorporate into the religion.39 Since this incident occurred before Olcott's trip to Japan, the invitation was presumably offered in the knowledge of the shortcomings of Olcott's mastery of Buddhism.

Because he perceived a relation between Northern Buddhism and Theosophy, Olcott was predisposed to discovering Theosophy in Japanese sects. "It is averred ... that the Shingons are the esoteric Buddhists of the country. They know of the Mahatmas, the Siddhis (spiritual powers in man), and quite readily admit that there were priests in their order who exercised them."40 "Esoteric" here refers not to the Japanese Buddhist technical term mikkyo but to the Theosophical use of the word as it appeared in Sinnett's Esoteric Buddhism, published in 1883, a sense specifically denied by Japanese Buddhist priests.41 Olcott's comment that Fenollosa and Bigelow's "Guru," presumably the Tendai master from Miidera, was "a mystic and partial adept (they say)"42 reveals both his expectations of Mahayana Buddhism and his skepticism that a Japanese Buddhist priest could have such powers. His skepticism was also apparent in his disparagement of Japanese paintings of Rakan (Sanskrit arhat, Buddhist sages). To Olcott they were mere "caricatures ... of Mahatmas."43 Japanese Buddhism was, after all, "debased modern sectarian Buddhism" and was to be measured against Theosophy, which was for him "regular Buddhism."

Japanese disdain for Olcott's understanding of Buddhism became apparent in 1891 when he returned to Japan with the draft of the pamphlet Fundamental Buddhistic Beliefs. This was a grossly simplistic reduction of Buddhism to a mere fourteen points "upon which all Buddhists could agree," which Olcott intended to use as the platform for the proposed International Buddhistic League. Like the Catechism, it presented Buddhism at the level of sophistication of a Sunday school tract. Olcott, misinterpreting the courtesy shown him on his previous tour, had expected his document to be signed by all the leading abbots, the promoters and supporters of his first visit. To his disappointment, the Japanese refused to sign "these condensed bits of doctrine," complaining that "there was infinitely more than that in the Mahayana."44 He persuaded one member of the committee to sign by arguing the vital necessity of the Northern and Southern churches offering a united front to a hostile world. However, even this endorsement appears with the qualification that the fourteen points are "accepted as included within the body of Northern Buddhism" as "a basket of soil is to Mt. Fuji," an attempt to avoid the implication that the extract represented the essence of Buddhism.45 A partial understanding of Buddhism was acceptable, even commendable, coming from a sympathetic Westerner. It could not, however, be endorsed as institutionally accepted truth, even as a political expedient.

Olcott did eventually manage to obtain signatures from representatives of most of the sects, if not at the level of authority he had expected. Among the Japanese names are those of Kazen Gunaratna and Tokuzawa Chieza, for example, two young priests sent to Ceylon to study Pali. They had no institutional authority and were guests at Adyar at the time. One sect that is not represented is the Jadoshinshu, from which came the principal benefactors of his earlier tour and, incidentally, the official, if inactive, representatives of the local branch of the Buddhist Theosophical Society formed in 1889. Olcott, upset at this rejection, fell back behind the defense of Western scholarship and its model of Original Buddhism as the ascetic, world-rejecting, and egalitarian teaching of the historical Sakyamuni. On his first visit he had favorably characterized the Jadoshinshu as "the Lutherans of Japan."46 After the rejection, he wrote that they occupied "an entirely anomalous position in Buddhism, as their priests marry-in direct violation of the rule established by the Buddha for his Sangha" (that is, they were not ascetic). They were "the cleverest sectarian managers in all Japan" (not otherworldly), and "the most aristocratic religious body in the empire" (not egalitarian).47 Olcott, the "champion of Buddhism," exploited the versatility of the Orientalist stereotype against modern Buddhists. Those who conformed to it were criticized for not meeting the needs of the modern world. Those who did meet the needs of the world were simply not real Buddhists and could be criticized for failing to uphold the ideals.