by Erik D. Curren

© 2006 by Erik D. Curren

Book Design: Pat Gibson

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Do not accept my dharma merely out of respect for me, but analyze and check it the way a goldsmith analyzes gold, by rubbing, cutting, and melting it. -- Sutra on Pure Realms Spread out in Dense Array

Table of Contents:

• ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

• CAST OF CHARACTERS

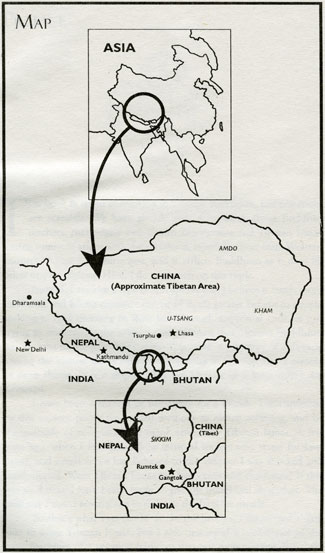

• MAP

• PREFACE

• INTRODUCTION

• Chapter 1: BAYONETS TO RUMTEK

• Chapter 2: THE PLACE OF POWER

• Chapter 3: AN ANCIENT RIVALRY

• Chapter 4: THE ORIGIN OF THE KARMAPAS

• Chapter 5: A LULL IN HOSTILITIES

• Chapter 6: EXILE, DEATH, AND DISSENT

• Chapter 7: THE TRADITIONALIST

• Chapter 8: THE MODERNIZER

• Chapter 9: A PRETENDER TO THE THRONE

• Chapter 10: ABORTIVE SKIRMISHES

• Chapter 11: THE YARNEY PUTSCH

• Chapter 12: UNDER OCCUPATION

• Chapter 13: LAMAS ON TRIAL

• Chapter 14: THE SECRET BOY

• Chapter 15: THE RETURN OF THE KING

• Chapter 16: CONCLUSION

• APPENDIX A: BUDDHISM AND THE KARMAPAS

• APPENDIX B: ANALYSIS OF ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS

• NOTES

• BIBLIOGRAPHY

• INDEX

• PHOTOGRAPHS

"In Tibet, the only dharma left is superficial teachings, so it is not worth your trouble to save it." -- The 10th Karmapa

***

During the next three days, the new Rumtek administration of Situ and Gyaltsab pressured the monks who had not fled or been arrested to sign a document affirming that they accepted Ogyen Trinley as the seventeenth Karmapa. On August 5, the police returned, again accompanied by Bhandari's party toughs from the Gangtok market. While the monks were assembled in the dining hall, the bullies and police entered. A group of the street toughs pulled the cook out of the kitchen and smeared chili powder over his face. They told him never to cook for the monks again. Then they put up a large framed photo of Ogyen Trinley and addressed the monks.

The leaders of the gang of toughs told the monks to perform prostrations in front of the photo as police looked on. "At gunpoint we were forced to accept Ogyen Trinley of Tibet as the one and only Karmapa," said Omze Yeshey. "We had to swear an oath on our acceptance. We were told that anybody who dared to say otherwise would face legal consequences." The intruders brought tape recorders to capture each oath. Then, the gang leaders drove the young monks into the kitchen and made them pick up the kitchen knives. They had to pose in menacing positions while the police snapped photographs, apparently to allege later that they were fighting. The police would create bogus criminal files for each monk.

Several of the street toughs carried knives and demanded keys to the monastery's prayer rooms and shrines. Just as they had refused to surrender the main temple keys three days before, so now the Rumtek monks would not yield the keys. This led to another stand-off. for six nerve-racking hours, the monks stood shoulder-to-shoulder in front of the door to the main shrine room, while Bhandari's bullies took up positions several feet opposite them, taunting the monks and periodically threatening to attack. The Sikkim police looked on without trying to stop the bullies or defuse the situation.

The stand-off was broken only by the appearance of more police officers at about five o'clock in the afternoon, this time elite security forces of the Sikkim Armed Police. With Situ and Gyaltsab leading the way, the soldiers chased the Rumtek monks to the back of the monastery. The monks locked themselves in a small storeroom. The soldiers and street toughs together broke down the locked door and began beating the monks, injuring twenty in the process.

Three Sikkim government officials -- Police Inspector General Tenzing, the fearsome Officer Suren Pradhan, and another policeman known as Kharel -- made a speech to the monks. They warned that unless all the keys were handed over, anything could happen. In response. the monks insisted that a monastery was a private religious institution protected by India's constitution from state interference. The government officials were not impressed with this argument, and they insisted on the keys. Finally, seeing that it was the only way to avoid further bloodshed, the monks handed over the keys to the police officers.

Officer Kharel then unlocked the main temple door and announced that from now on, Situ Rinpoche would control Rumtek. Later. the Sikkim home secretary handed over all the keys to Gyaltsab Rinpoche in exchange for a signed receipt.

Finally, the police arrested more monks. "A considerable number of our monks was illegally detained and locked up in police custody for several days," said Chultrirnpa Lungtog. Monks who were not arrested fled the monastery to take refuge in the surrounding forest. After the week was out, about a hundred monks, or ninety percent of Rumtek's original monks before Situ started bringing in outsiders in 1992, left Rumtek rather than accept Ogyen Trinley as the seventeenth Karmapa.

"We were no longer allowed to enter the monastery, so we had to find somewhere else to stay," said Omze Yeshey. "This is why we had to seek refuge in Shamar Rinpoche's residence, where we could be close to the Dharma Chakra Center. He himself wasn't there. No preparations or earlier arrangements had been made. In fact it was very difficult. The house isn't that big, and we were a considerable number of monks. So we had to contend with numerous problems in terms of our accommodation."

"It is deemed strange," wrote the Hindustan Times, "that pro-China Situ Rinpoche, who has never in the past taken up any responsibilities at Rumtek has suddenly chosen to muster the Sikkim Chief Minister's support, to execute a coup d'etat, while regent Shamar Rinpoche is abroad." [4]

***

In the late eighteenth century, at the time of the tenth Shamarpa Mipham Chodrup Gyatso (1742-92), a tragedy befell the line of the Shamarpas that would remove them from Tibetan public life until the middle of the twentieth century. The role of the tenth Shamarpa has been hotly contested by historians and journalists. It has become a test of the current Shamar's fitness to recognize the seventeenth Karmapa -- or to object to the recognition of Ogyen Trinley.

"Tibetan Buddhists believe that karma from one's past actions or deeds can cling to a person through many lifetimes," wrote British reporter Tim McGirk. "That is why many Tibetans explain the odd behavior of a lama named Shamar Rinpoche by referring to an event 202 years ago. In his incarnation then, Shamar Rinpoche was a monk so overcome by greed that he lured the Gurkha army into attacking a monastery for its treasure." [5]

Lea Terhune echoed this view in Karmapa: The Politics of Reincarnation: "The Gurkhas had been spoiling for a fight with Tibet. In this they were helped by the Shamarpa, who is credited by historians with instigating the Gurkha War with alluring descriptions of the riches at the Panchen Lama's monastery, Tashilhunpo, and egging on the Gurkha king." [6] Later, we will see how McGirk and Terhune worked as colleagues in New Delhi in the 1990s, so it would not be surprising that they shared the same interpretation of Tibetan history. In this case, their views appear to derive from the well-known history of Tibet by former Lhasa official Tsepon W.D. Shakabpa, whom we met in chapter 3, where we discussed his biased account of the fifth Dalai lama's rise to temporal power in the seventeenth century.

In his book, Shakabpa blamed the tenth Shamarpa for starting the Tibet-Gorkha war. After the Dalai lama's government intervened to prevent the Nepali Gorkhas from conquering Sikkim, Shakabpa wrote:The Gurkhas were annoyed at the Tibetan interference and were looking for an excuse to attack Tibet. An excuse was found in the controversy over the third Panchen Lama's personal property, which was being claimed by the Panchen's two brothers, Drungpa Trulku and Shamar Trulku; the latter was the ninth [sic] Red Hat Kar-ma-pa Lama named Chosdrup Gyatso. Shamar Trulku hoped to use Gurkha backing for his claim to the Panchen Lama's property in the Tashilhunpo monastery; while the Gurkhas wanted to use his claim as a pretext for invading Tibet. [7]

Shakabpa's interpretation of the Shamarpa's role in the Tibet-Gorkha War has been disseminated widely. Yet, as in the case of Shakabpa's account of the rivalry between the Karma Kagyu and the Gelugpa that led to the Dalai Lama's ascension to power in 1642, his story of the tenth Shamarpa does not agree with standard Tibetan historical sources of the period. [8] These sources show that Shakabpa is too easy on the Tibetan government of the time and too hard on the tenth Shamarpa. This is not surprising, considering that Shakabpa was a minister of the old Lhasa government, since the seventeenth century the historic enemy of the Shamarpas.

Tibetan chroniclers -- especially a general named Dhoring who led Tibetan forces in the Gorkha War and provided an eyewitness account of the major players involved -- are much more sympathetic to the tenth Shamarpa. These historians explain that while trying to claim his portion of a family inheritance, the tenth Shamarpa unwittingly became a pawn in a conflict between Central Tibet and its overlord China on the one hand, and Nepal and the British in India on the other. The outcome would have disastrous effects for the future of the Shamarpa line.

In the past, the Shamars and Karmapas sometimes appeared in the same family, as the fifth Shamarpa had predicted. As we have seen, the current Shamar is the nephew of the sixteenth Karmapa. However, in the eighteenth century, the Shamarpa took birth in the family of the second most powerful lama of the Dalai Lama's Gelug school, adding an unusual political twist. The tenth Shamarpa Mipham Chodrup Gyatso was born in 1742 in Tsang province as the half-brother of the third Panchen Lama Lobsang Palden Yeshe (1737-80). The Shamarpa was thirty-eight years old when his half-brother, age forty-three, died of smallpox while on a visit to the Qianlong emperor in Beijing in 1780. The emperor gave a substantial sum of silver coins as a condolence to one of the Panchen's brothers, known as the Drungpa Hutogatu, to distribute to the Panchen's family. The tenth Shamarpa and the Drungpa clashed about these funds.

The Shamarpa argued that the bequest was intended for the Panchen Lama's family, and as a half-brother of the late Panchen Lama, the Shamarpa claimed a portion of the emperor's gift. But the Drungpa refused to share the Chinese funds, saying they were intended for the Panchen Lama's Gelugpa order. Perhaps fearing that this position would not stand up in court, the Drungpa, who like the Panchen was a lama of the Gelugpa order, enlisted allies in the Lhasa government. We have seen how the Gelugpas came to enjoy government patronage after the fifth Dalai Lama took power in Lhasa in the seventeenth century. By the 1780s, government preference for the Gelugpa over the other religious schools had become established practice.

The Drungpa found a willing ear in the regent Ngawang Tsultrim, who had refused to relinquish effective control over the government after the eighth Dalai Lama Jampal Gyatso (1758-1804) reached adulthood in the late 1770s. Regent Ngawang apparently saw in the dispute between the Drungpa and the Shamarpa a pretext to accomplish three long-cherished political goals: to extend the power of the Gelugpa school further over its old rival the Karma Kagyu; to settle a long-running trade dispute with Nepal, where Shamar had powerful supporters; and to assert Tibetan autonomy against Nepal's patrons, the British East India Company's administration of India, which had been trying to establish trading posts inside Tibet. The Tibetans and their Chinese overlords feared that trade relations with the East India Company would open Tibet to British interference and perhaps even colonization.

The Qianlong emperor was particularly nervous about European encroachment on his empire, of which he considered Tibet to be a part. Qianlong is known in the West as the Chinese ruler who rebuffed Britain's commercial overtures in 1793, only a year after the Gorkha War, arrogantly informing King George III's envoy Lord George Macartney that the British had nothing to sell that the Chinese wanted to buy. Fifty years later, Anglo-Chinese tension would explode into the Opium War of the 1840s. In the late eighteenth century, as this tension began to grow, Qianlong was as eager to exclude the British from Tibet as he was to keep them out of the port cities of southeastern China.

The Shamarpa had great influence in the kingdom of Nepal. In the early years of their partnership, the Karmapa and Shamarpa had divided Tibet into geographical spheres of responsibility. The Karmapa would teach Buddhism in eastern Tibet, while the Shamarpa would cover the south. Historically, this southern region included Tibet's neighbor Nepal. Over the centuries, the Shamarpas gained thousands of followers there, and the Shamarpas came to serve as spiritual advisors to prominent noble clans and even to the royal family. Shamarpa influence in Nepal continued even after the invading Hindu Gorkhas overthrew the Malla kings of the Kathmandu valley and consolidated their power over the formerly Buddhist kingdom in 1769.

In Lhasa in the early 1790s, Regent Ngawang convinced important Central Tibetan officials and, more importantly, the Chinese Amban, the de facto ruler of Tibet, that the tenth Shamarpa was about to betray Tibet to Nepal and to the Gorkhas' British allies. The regent claimed that the Shamarpa had invited Gorkha forces to cross into Tibet, first to help him claim the wealth of the Panchen Lama and then to go on to Lhasa to pillage the city and force on Tibet a trade agreement favorable to Nepal. The regent was able to make these charges stick at the Dalai Lama's court and a warrant was put out for the Shamarpa's arrest. To escape capture and likely torture and execution without trial in Lhasa, as was Tibetan custom at the time, the tenth Shamarpa fled for safety to Nepal in 1791.

Nepal's King Prithi Narayanan Shah gave the Shamarpa political asylum -- and, to preempt a Tibetan invasion, he sent an expeditionary force across his northern border and into Tibet. Meeting little resistance from the small, poorly trained Tibetan army, the Gorkhas advanced towards Lhasa and prepared to take the city. To avert the capture of their capital, the Tibetans were required to call on the Chinese for help. It response, the Qianlong emperor sent thirteen thousand troops to join a Tibetan force as large as ten thousand to halt the Gorkha advance. The imperial army arrived just in time to prevent a total Tibetan rout, and the Gorkhas were turned back and put on the defensive.

Meanwhile, Regent Ngawang Tsultrim died in Lhasa. Karma Kagyu lamas said that their school's protector deity, Mahakala, had punished the regent for his attack on the Shamarpa. The regent was succeeded by his deputy Tenpai Gonpo Kundeling, who continued to sideline the Dalai Lama as his predecessor had. On his own initiative, the new regent concluded the war, with terms to his own advantage.

With Lhasa no longer under threat of being sacked by Gorkha cavalry, and with the power of the Shamarpas broken in Tibet, the regent could make use of the property of the maligned Red Hat Karmapa. Tenpai Gonpo confiscated the Shamarpa's monastic seat at Yangpachen and put it under the control of the large Gelugpa monastery Ganden, one of the powerful Three Seats. Dozens of other Shamarpa monasteries were forcibly converted to the Gelugpa order by official mandate. Regent Tenpai Gonpo personally took possession of the tenth Shamar Rinpoche's residence in Lhasa and turned it into a police court and lockup, where accused prisoners were subjected to physical mutilation and other tortures. [9] The regent then convinced the Qianlong emperor to issue a decree that forever after Shamar Rinpoche was prohibited from reincarnating in Tibet. The Lhasa government would enforce this distinctive punishment for the following two centuries.

The tenth Shamarpa died in 1792 in Nepal. Historians have speculated that he was poisoned by either the Nepalis or by Tibetan agents. But the current Shamar told me that his predecessor decided to transfer his consciousness out of his body through the practice of phowa -- essentially bringing on his own death -- to escape capture and torture by the Chinese. His body was cremated in Nepal, but this did not stop the victorious Qianlong emperor from demanding the the Nepalis hand over the ashes and charred pieces of bone, and taking them back to Beijing to undergo a ritual punishment as a warning for others, according to Qing dynasty custom.

Back in Tibet, the Shamar labrang was dissolved and the people and property attached to the Shamarpa under Tibet's feudal system were taken by the government or distributed to various Gelugpa and Karma Kagyu lamas. In light of the Lhasa government ban, no Karmapa could recognize or associate with a Shamarpa on an official basis. To avoid military reprisals against Karma Kagyu monasteries from the government of Central Tibet, the Karmapa observed the ban in public. In private, however, the Karmapas continued to recognize successive reincarnations of the Shamarpas for the next century and a half. [10]

-- Buddha's Not Smiling, by Erik D. Curren