Part 1 of 3

In a Zen Monasteryby Muriel Daw

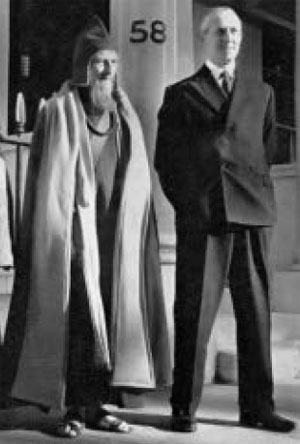

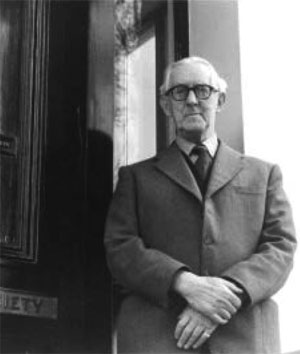

With much gratitude to the Venerable Roshi Soen Nakagawa, Abbot of Ryutakuji, and Toby, otherwise known as Christmas Humphreys, founder of the London Buddhist Society and the leader of its Zen group until his death in 1983When I was in a Japanese Zen monastery working under Soen Roshi, he paid me only one compliment all the time I was there. He said approvingly, ‘You the only Westerner I know who doesn’t want to talk about Zen.’ In the light of that, you may well wonder what I am doing now. Many books have been written and many lectures given about Zen. But is there any Zen in them? For me, Zen is not something to talk about and discuss. There is no such thing as abstract truth; there is only reality. As Keats said, philosophy will clip an angel’s wings. Bodhidharma, the founder of the Zen school, described Zen as:

A special transmission outside the Scriptures;

No dependence on words or letters;

Direct pointing at the Mind of man;

Seeing into one’s own Nature; and the

attainment of Buddhahood.

The nature of Zen is the true nature of each thing or person. The Zen of snail-ness was caught by the poet Issa when he said,

O snail,

Climb Mount Fuji,

But slowly, slowly!

I have seen my roshi stand in front of a wild lily, and bow before it, then pick it for a vase in the temple. The very picking was a natural ceremony. That was Zen, but my telling you about it is not, so that is no good.

It is all very well saying that the universe is one interdependent whole and that each separate one of us is that whole. This is a perfectly sound statement of the way things really are, but unless each one of us really knows it for himself – so what? And this experience can be found only inside ourselves. Buddha means awakened, and it is only we who can awaken. It is said, ‘When you awaken, it is your own mind that is awakened. If you look for a tangible Buddha somewhere outside, you are foolish. It is like a man looking for a fish: he must first look in the water because that is where you find fish.’

I cannot write about Zen, but I can tell you what it feels like to be in a Zen monastery and to be in the presence of a roshi who lives totally and universally while manifesting his true self in each moment as he experiences it. Perhaps you may be able to get a trace of the fragrance of Zen.

Zen in Japanese, Dhy›na in Sanskrit and Ch‘an in Chinese, all translate as meditation, which means to be still and focus the mind; inner vision. So, the Zen School is the Meditation School, and we can talk about that quite easily. But Zen itself is the realization of what is experienced during that meditation, and this cannot be talked about. It has something to do with that state of mind in which we are not separate from other things, are indeed identical with them, yet retain our own individuality and personal peculiarities.

I once heard a roshi give an ‘as-if’ explanation of Rinzai Zen methods. He said that when one becomes completely discontented with being in the suffering world of Samsara and doing things that seem worthless – what we might call ‘the divine discontent’ – it feels as though the whole structure of relativity surrounds one; and there arises a longing to break completely out of the whole thing and see reality for ourselves.

The structure surrounds and traps us as though we were living in a prison. It is like being in a greenhouse made of frosted glass, and in meditation we attack it. Some people start breathing and rubbing at the frosting until they can see through a large patch, but it is dim and smeared. Others start scratching away with a fingernail until they get a bright peep-hole; but although sharply clear, it is very tiny. We must try to shatter the whole thing and find that ‘Nothing exists except pure radiant mind.’

It is a school in which the immediate eagerness for ‘Enlightenment here and now’ directly permeates all everyday actions. It cuts through emotions, intellect, and all swollen-headed perceptions of ourselves. We have only to remove our own shadow, which is much harder than it sounds, in order to experience the light that is ever-existent. It is a way full of hard work, joy, beauty and the laughter of true freedom.

Of course, simply being in the presence of an enlightened roshi is a spiritual training in itself. There are no habit-formations, so every one of his actions is new, fresh, creative.

The pupil has to leap up to the master’s level of insight to experience it, because if the teacher brings his level down to words and talking, well, we might just as well read a book.

A Zen master will resort to any means he can think of to make us realize the truth of all pairs of opposites.

He sternly demands: see this stick – it has two ends – Now, what else could you call the ends? Give them another name!

Two ends of a stick indeed! There is no such thing. It is not cut into two ends and if it were, how many ends would there be? It is one stick, one wholeness, one stick-ness, and to name it as anything at all is miles away from the real-ness of it. Talking about a stick bears no relationship at all to the thing in itself. He is just tricking us into low-level relative argument; and we are silly if we let ourselves be tricked. Still, we learn by it. One day, if he asks such a silly question about names for two ends of a stick, someone will show him the function of a stick and threaten to beat him with it.

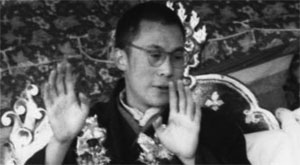

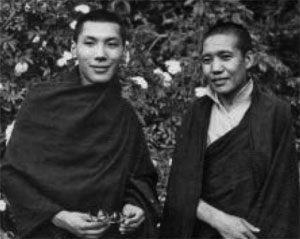

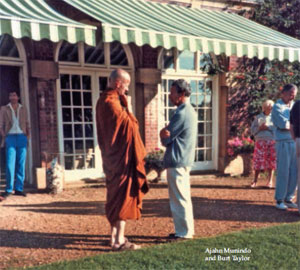

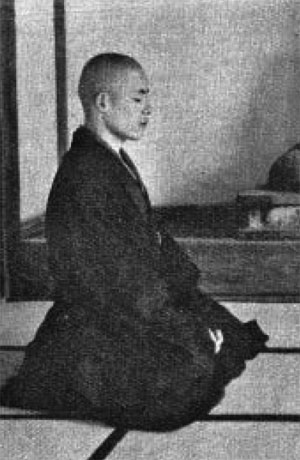

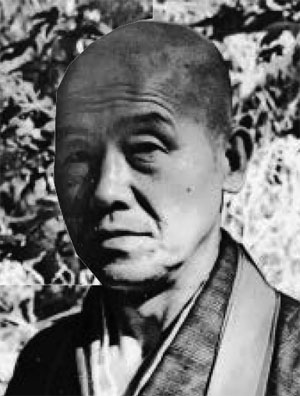

Soen Nakagawa Roshi

Soen Nakagawa RoshiZen is the direct way – straight up the mountain-side. If you like to take the path that spirals round the mountain, that’s fine. It eventually leads to the same place. But that means following another school.

The Buddha’s BirthdayThe eighth of April is celebrated as the Buddha’s birthday in Japan. On the eighth of April, 1963 in England, [I was 40 at the time], a harassed airport official telephoned the Buddhist Society and said, ‘We have a VIP stranded overnight, and he is a Zen Buddhist abbot. What should we do with him?’ Toby said promptly, ‘Put him in a car and send him here. We’ll look after him.’

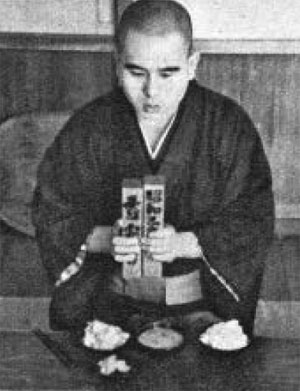

That evening, the Zen class at the Buddhist Society had Soen Roshi as an honoured guest. We were delighted, not only was he a roshi, a teacher of exceptional standing, but he also had a fair amount of English.

At that time Soen Nakagawa, Abbot of Ryutakuji Monastery, was the only Japanese roshi who could speak English, and he had landed in London – by accident?

Towards the end of the evening he addressed one personal sentence to me about the Heart Sutra, a short Buddhist scripture. The heavens shattered, creation dissolved about me, the solid wholeness of the universe seemed to be present in a lightning flash. I was totally confused. Quite helpless, I muttered some inadequate response, and for the next few days was conscious of nothing else. I was blind and deaf to all other matters.

PreparationIt took me two years to get to Japan, but I knew I HAD to work under this man who could play with universal awareness as though it were a violin. People said to me patiently, don’t be stupid. He’s the abbot of a monastery. Monasteries don’t take women! I took no notice. I learned a few basic words of Japanese.

I practised a lot of zazen sitting. I never could sit in the lotus position, but I managed. I re-arranged things at work in order to take several months’ leave. I continued to work hard in the Zen class, and recited the Heart Sutra to myself practically non-stop. And I found out as much as I could about life in a Zen monastery.

There is always a very tough probation before being accepted by a Zen teacher: the would-be pupil has first to prove both determination and ability to stand any amount of hardship. Zen is the direct way and is only for those with intense determination and longing for truth. Imagine someone holding your head down under water until you are choking. Only when your need for Enlightenment is as great as the need for air will you feel the need for Zen monastic training.

TraditionHere is a little about Japanese tradition before I tell you what happened to me. In Japan people do not separate religions as we do, and families belong both to a Shinto shrine and to a Buddhist temple.

Shinto is the ancient religion of Japan, and consists of worship of the kami, the spirits, with much purification and dignified ceremony. The kami are rather like the Olympian Gods and Heroes, with all their legendary history, celestial grandeur, and robust earthiness. Sometimes a particular tree or rock is a kami and has a special sacred rope around it, marking it off from this secular world. Some historical emperors and heroes are kami – they have a special numinous quality. Thomas Edison lived a while in Japan, and with his power over electricity he was obviously a genuine kami. After he died, a Shinto shrine was built to him, and you can go there at any time to pay your respects to Edison and worship him.

Every Japanese baby is born into Shinto, and in their early days, babies are ceremonially presented at the shrine to which the family is attached. Shinto is a religion that, like Confucianism, has very clear ideals of behaviour to family, ancestors, the state, and, above all, the Emperor.

The growing youngster will perform all his duties to family, school, and then employer, under the auspices of Shinto. Marriage will be celebrated with a Shinto ceremony (and maybe with a Christian one too if he is modern and broadminded, and likes to be thought fashionable). But when midway through life and having presented his own children at the Shinto shrine and watched them become independent, he will usually change to Buddhism and start attending the temple to which his family is attached. In the afternoon and evening of his life he has different needs, and these must be respected. Eventually he will be buried by Buddhist rites. So within each family, some members follow Shinto and some Buddhism.

Japanese boys tend to be much less individualistic than Westerners, and if one boy turns out to have a vocation for Zen Buddhism among all his Shinto companions this is quite outstanding.

His parents will take him to the local Zen temple (not a monastery); and if his character and sense of religious urgency seem strong enough, he will be accepted as a novice. From that time on, he will live in the local temple, going from there to school, and then to university if he is academically minded. There he would take Buddhist Religious Studies, and probably classical Chinese and Sanskrit.

Living in the temple, he gets up for an hour’s ceremony and meditation before breakfast. He studies the Buddhist scriptures, helps with public ceremonies, cleans the temple, and acts as attendant to his teacher. He learns to perform all physical actions quickly, adeptly and in a Zen spirit.

If he flourishes in this atmosphere and his intent is eager and firm [it needs to be very strong indeed], his master will prepare him for entry into the monastery when the time is ripe. He will also warn him of the coming hardships. A would-be monk has a very tough probation before he is accepted.

One day the young man sets off carrying a very small pack with only bare necessities. When he reaches the monastery, he enters the compound and bows respectfully at the main door. He begs for admission and presents a letter of introduction from his teacher. Back comes the answer: ‘No room, we have as many monks as we can feed,’ or some such reply, and he is refused admission.

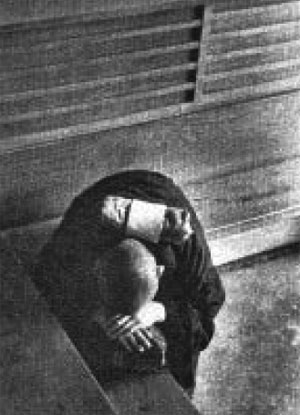

Motionless for several days.

Motionless for several days.The would-be monk does not leave. He puts his pack on the high step, kneels down on the ground with his head on the pack in a supplicating position, and does not move. He stays motionless in this position for several days, and refuses to budge.

Every few hours, three or four burly monks come and punch him, beat him up, and throw him out, slamming the gate. This gives him a chance to stretch and relieve his aches. Next he sits cross-legged outside until the gate is opened to admit someone else and then he can slip in and resumes his supplicating position at the front door.

Each night, he is grudgingly allowed entry to an outer guest room, where he does not lie down, but sits in lotus position all night. Next morning he is given a bowl of rice and is thrown out again. So it goes on, until he has proved both his determination, and his ability to stand any amount of gruelling hardship for the sake of being allowed to search for truth under the guidance of the roshi, the old Teacher.

Eventually, after five or seven days, if the would-be monk has withstood the test, he is admitted to the guest-room for three days of probation. Only after that can he be admitted to the monastery proper.

One day in the future, he will roar with laughter at the memory of those terrifying monks all punching and beating him. He will learn for himself exactly which muscle to pummel when it aches, how to hit hard enough to give relief to the great trapezoid muscles, and the best way to knuckle the spine into giving a glow of life through-out the body.

A monk does not make a life-long profession, but requests permission to train in the monastery for a certain length of time, probably three years to start with. During this time, his head will be shaved, he will keep the Monastic Precepts, and he will live a celibate life. For these first three years no academic books or scriptures are allowed. Only immediate experience will help him; academic knowledge is useless. At the end of this time he will either return to the world or ask to stay on again for another period. If people come in wishing to stay for life, they will continually renew their commitment. Others may wish to spend only a few years in meditation in order to deepen their insight before coming out again.

Eventually comes the day of the new monk’s first interview with the roshi, and he will ask to be allowed to stay in the monastery for an agreed period. He is given a meditation practice by his new teacher. It may be counting the breath, counting each out-going breath. ONE, TWO, THREE, up to TEN, and then again 1 to 10, interminably. It is not a matter of focusing on each number, but on so much becoming the number itself that there is nothing but that one number in the whole universe.

Or he may be given his first koan, an unsolvable spiritual riddle, as a meditation theme. For the first stage in Rinzai Zen one of the following three koans for beginners is usually given:

A monk asked Joshu ‘Has the dog a Buddha-nature or not?’

Joshu answered ‘MU’ [‘No’ or ‘No–thingness’].

Listen to the sound of the Single Hand.

Thinking of neither good nor evil; at this very moment what is your original face before your father and mother were born?

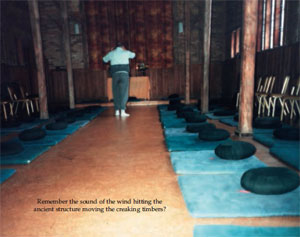

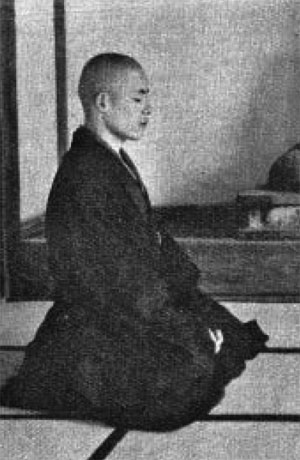

Next the new monk will be taken to the Meditation hall, and be shown the place where he will live. It is a strip of rush matting, three feet by six feet. There he will have his mattress, which in the day-time will be rolled up to use as his seat for zazen meditation.

There, in a row with all the other monks, he will spend his first three years. When get-up bell rings at four in the morning, they rise together, chanting while they put on their robes. In file they will use the toilet, and rinse their mouths; and within ten minutes they will be seated in rows in the Great Hall for the early morning ceremony. During the three training years, all meditation and work will be performed together, and be performed with dignity, beauty and harmony.

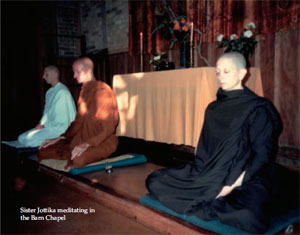

The rhythm of the day will afford no indecision or hindrance to the importance of the chief task, which is maintaining complete absorption in the koan. Meditation, chanting, communal work, and the begging round – these go on throughout the year. Every fourth week of the meditation term is Sesshin Week, which trained lay-people may also attend with special permission.

The Sesshin WeekEveryone gets-up at 3.30 a.m. and there is only a little communal work. Hour after hour of meditation is given to the koan, in lotus posture. Private interviews are held several times a day with Roshi. These are no gentle spiritual talks; but urgent, intense, sometimes violent, as the monk throws his whole being into breaking the barrier that holds him in the bondage of his own illusion. He is fighting with all his strength to get his head above the water that is drowning him. He knows that his koan is the only way through.

He knows that his own greed, hatred and ignorance are the three things forming a thick cloud around him, and he needs to get through this cloud. He needs to wake up, to cease looking at the universe through his own personality of ‘what I like’ and ‘what I don’t like,’ which can only distort his view. His first insight into what things are really like is called kensho, and once this is experienced, he has real incentive to continue with the training.

The sesshin is a week of physical agony and spiritual tension. At the end of each day, the monks file, exhausted, back to the Zendo taking off their robes while chanting. They lie down, each straight on his mattress, lying on his right side, head resting on his right hand. And so ends the communal day.

But the koan is still there, and so is the picture of Roshi waiting like a lion ready to pounce at the special sanzen interview the next morning. One after another, silent forms slip out of bed. Some sit and meditate under the eaves of buildings; some like to go down to the cemetery; others prefer the woods: all silent figures sitting cross-legged in the moonlight. But by 3.30 in the morning, there are the straight lines of monks in bed, lying on their right sides and ready for the get-up bell.

Sesshin week gets worse and worse. Nerves are strained to breakingpoint. The tension rises. Then, usually around the fourth day, there is a sudden lull, and every-one gets his second wind. What has for each been an individual life-and-death struggle, becomes a harmony. Face-to-face confrontations between Roshi and pupil are still intense, but they have a deeper multi-dimensional quality in this new atmosphere. The week continues like the last movement of a concerto building up to its great climax.

Monastic life is natural and cyclical. Spiritual growth takes place in rest periods alternating with sudden flowerings.

At the end of the three years of communal training, the monk’s future will be decided. Maybe he will go back to lay life. Zen training is highly regarded in the business and academic worlds. Or he may go home to the farm.

Perhaps he wishes to take office in a small local temple, the equivalent of our village priest. If he aspires to a larger place, he would not be accepted without at least 10 years of training in the monastery.

Of course, by this time he may love monastic life. If he stays on, he will probably be given a room of his own, be allowed to read and study again, and to a certain extent to follow his own tastes. He will take his turn in responsible posts in the running of the monastery, and perhaps even be a roshi himself one day.

To RyutakujiTwo years after the visit of Soen Roshi, I wrote asking permission to enter Ryutakuji Monastery as a lay-woman for one term (three and a half months), and enclosed an official letter of introduction from Toby. Back came the answer. I was accepted for one week only. The letter told me that it was a monastery (not a nunnery), and that there were no facilities for regular lay-people. However, I might come to a sesshin week when a few other lay-people would be present. I was recommended to go after that to a meditation place for women 60 miles away.

Oh dear! ONE WEEK! I certainly could not afford to go all the way to Japan for one week.

My next thought was: ONE WEEK, well, that’s fine, I defy anyone, Zen master or not, to get me out of that monastery once I’ve got my foot in the door.

The first impact was sheer beauty: a steep valley in the foothills of Mount Fuji; paddy-fields terraced all the way; a tiny village with a stony path leading to the forest on the hill-side beyond; stone steps flanked with masses of rhododendrons and huge butterflies; and up, up to the great monastery gate and a group of perfectly-shaped buildings with winged eaves hung with little bells. The background to everything indoors and out was always a sheer, breath-taking beauty.

Next day I had my formal interview with Roshi – I was terrified. I made three full length prostrations; I saw an inscrutable face with a cold courteous nod as I presented my gift. Of course, I asked to stay the whole term. A shrug of the shoulders – the monastery was run by and for monks. I asked again. No, there was nowhere I could sleep outside so that I could come in by day. I asked for the third time: PLEASE. Well, he would tell the chief monks to watch me very carefully during the week; and he rang his bell, which means instant dismissal. I bowed and left.

The next day a monk formally returned my gift, still wrapped. ‘Thank you, but Roshi does not need it.’

That was worse than a slap in the face. For a Japanese to return a gift is a deep insult. It is a very clear way of showing intense displeasure. During my interview I had felt that he had not recognized me, although with his phrase about the Heart Sutra he had turned my whole world inside out two years ago.

That sesshin was hell, but I loved every minute of it. However awful all the surface things were, inside my heart I knew that for this part of my life, here was where I belonged.

Such was my confusion during that week, that I only recall fleeting glimpses. And always the eyes of the three chief monks were on me: eyes watching when I lost my place in the sutra book; when it seemed impossible to manage my chopsticks; when I moved during meditation; eyes watching my dreadful ungainliness, and my constant struggle to keep in time with the beauty of all the movements of the monks in their flowing robes.

I remember tagging along as the last of the long line and the terrible moments when I lost my end place in the file. We would cross the courtyard, kick off our straw sandals and go up the steps and through a chain of buildings. Then the procession would perhaps go through the Zendo and out the other side. As I could not follow through the monks quarters, I had to race back to the door where I had left my sandals; chase through the courtyards and gardens, and try to discover where they had got to so that I could tag along at the end again.

I was never in the right place at the right time. I had no idea what the various signals of bells, gongs and clappers meant. Everyone else knew what to do, but I did not. There was no-one to ask – they did not speak English. Anyway there was a silence rule, and if I bothered the monks, they certainly would not let me stay.

Hours on the meditation cushion I had expected, but somehow I had not realized that everything else would be even worse. How did one kneel back on one’s heels for an hour each day for the daily teisho (sermon)? And there was just the rush matting, not even a cushion – and one had to sit MOTIONLESS, with calm face, and eyes lowered in meditation because to twitch or to move would have been disrespectful. And was my spine quite straight? I could feel the eyes of one of the chief monks boring right through me. And then there was the kneeling back on one’s heels again for meals. During sesshin week one spends 12 hours each day either sitting cross-legged on a cushion or kneeling on the floor. By the end of the week the fronts of my feet were badly split and bleeding. They did not heal properly during all the time I was there.

Then there was more kneeling [this time motionless on hard-ribbed matting], for over half an hour while waiting for my first sanzen interview with Roshi. The monks call the sanzen room ‘the tiger’s cave.’ Despite all my efforts for two years to come and work under Soen Roshi, I dreaded presenting myself again to meet those inscrutable eyes. I knew he disliked me; he had returned my ceremonial gift. He would, of course, give me 1 to 10 counting practice because I was a beginner. I hadn’t been working at Zen as a novice for years beforehand.

Kneeling, waiting, the moment came. I struck the gong twice, as I had seen others do, and went along the passage, over a running stream, up the stairs, I made three full-length prostrations outside the door, three more inside, then three more face to face with Roshi. Miracle of miracles! I was given a koan!

And then that diabolical man said, ‘Of course, each meditation period, must calm mind first. Start by counting breath 1 to 10. Whenever anything else at all flickers into mind, stop, go back to one. When you’ve reached 10 about 8 or 9 times, then koan.’

Believe me, I may have been officially given a koan: but back on my meditation cushion, could I ever get to it? – I hardly ever reached beyond counting. Such a medley of new experiences, and so much mental stress and physical pain seemed to put calmness of mind completely beyond possibility. And that was what I was there for.

For instance, I shall never forget that first sesshin morning. The get-up bell would ring at 3.30, but I knew I could never get up, wash, dress, cross the compound and be standing by the Great Hall ready quietly to slip into my place at the tail-end of the file in ten minutes. So I set my alarm for 3.l5 a.m. It would be an hour’s ceremony, then meditation, including Sanzen, for another hour-and-a-half. Nothing to eat or drink till 6 o’clock breakfast. But suddenly, Joy oh joy! At about 5 o’clock, a monk appeared with a huge teapot. We all bowed our thanks and held out our tea-bowls. I took a deep gulp of the lovely steaming liquid. It was hot, very salty water – brine. We were supposed to be striving so hard with our koans, that by now we should be sweating and need some salt intake.

Then there was the Chief Monk of Discipline walking round with the stick. Nowadays this kind of thing happens often outside Japan; but then one had only read about it, and it was unnerving at first. He has a flat stick, the keisaku and he paces round. You are never hit with it unless you request it by bowing. When one has been sitting a long time, the spine aches and shoulder muscles feel awful, and then it is very welcome. On the other hand, you may feel fine, but he thinks you need it. If so, he just stands in front of you, waiting, and you realize your number is up, and politely put hands together asking him to hit you!

I was just beginning to get the hang of things; knowing where I was supposed to be and when, by the time that terrible week ended. Needless to say, I had not yet spent much time on my koan, but I had been counting like anything. The whole thing had been a wonderful experience. The other lay-people packed up and went home, and I was left alone with the monks. Can you imagine how anxious I was about the verdict?

I asked if I might see Roshi, and was told: tomorrow; then the next day, tomorrow; and then again – tomorrow.

At last a monk came. ‘Daw-san, Roshi.’ So off I went to his room. I had a coldly formal reception, never a smile. [And he had seemed such a radiant person when in London.] Nevertheless, I was given tea and told, ‘Monks don’t mind if you stay; but no proper room. You can sleep over storeroom.’

My Probation Was OverHow happy I was. One end of my room was the store for the picture scrolls, chests of robes and ceremonial altar hangings; and the other end was full of spare meditation cushions, mattresses, quilts, and bean-bags. These last were pillows – bags stuffed with dried beans and most uncomfortable. I helped myself to a mattress, a quilt, and then an extra quilt to roll up for a pillow and then I unpacked my bag, and made myself at home. Now this was REALLY my home for the next three months.

There were two windows. One was very large and would not open, but it looked out over the main courtyard and I could see everything that went on. The other was very small, but unglazed, and therefore would not shut. The room was up under the roof and got unbearably hot in summer, but fortunately a very large and friendly striped spider made a web right across my unglazed opening and kept all the mosquitoes out.

The really odd thing about my room was the way the monks treated it. Sometimes it was Daw-san’s room, and sometimes it was the storeroom. There would be a polite scratch on the door, and a monk bringing a letter. They practically fought each other to bring my post, and then stood waiting hopefully for the foreign stamp. Or at other times it would be a polite scratch and – ‘Daw-san, Roshi.’ But sometimes it was the storeroom: No scratch on the door – a monk flying straight in, and rushing to one of the chests, whether or not I happened to be washing or dressing. Once, when there was a panic on over a funeral, six monks came into my room before four in the morning. Eventually I found a lovely gilt screen and fixed myself a little dressing-corner.

A Zen monastery is a very strict affair: full-time Zen training is only for those who are completely dedicated. For instance, when a bell rings, one immediately drops whatever one is doing, and turns to next thing to be done. Suppose you are writing a letter home. At first, you finish the sentence and leave the rest till later. As the training proceeds, you finish only the word you are writing, and think ‘I’ll finish that tomorrow.’ Later, you hone it down finer and finer, until the bell rings, the pen drops [even in the middle of a letter in the middle of a word] and there is no thought of finishing at any time, but simply openness to the need of the moment.

One day, there was a snake in my room. It was quite big, about 4 feet long, and it disappeared among all the cushions and quilts. I went down to find a monk, and fortunately I happened to know the Japanese word for snake, hebi. Soon four monks arrived with the snake-kit. Two carried a long hollow piece of bamboo on ropes; one had a drum; and the fourth brought a giant pair of bamboo chopsticks.

The theory is that you make a noise with the drum that scares the snake out of its hiding-place. Then you catch its neck with the giant chopsticks, and push its head into the bamboo pipe. It can only wriggle forwards, so when it is in, you clap something over each end, carry it away in the pipe, and let it free in the forest. Simple!

Unfortunately, my snake wouldn’t be frightened out. [Maybe it had been caught that way before.] After much searching through a large area, with bedding stuffed high to the ceiling, the four monks gave up. All together, with much laughter, they gave me a graphically mimed description of how to suck a snake-bite wound and spit heartily. Off they went, chuckling.

The next few mornings, as I got up long before dawn and went barefoot down the stairs, I wondered whether the snake or I should be more scared if I stepped on it in the dark.

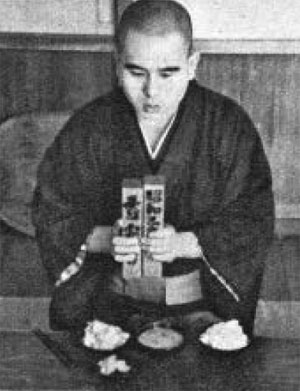

I happily started fitting in to the monastery routine. Morning ceremony and meditation. The ritual and the chanting always moved me deeply. To see and feel form perfectly carried out in order to let life flow through is awe-inspiring. Power builds up and builds up until there are voices chanting that are certainly not our voices. Then starting to make the power useful – our vows, always a very meaningful moment in the day; the circling sutra of the monks, channelling the rhythmic power into real live movement. Then the best moment of all: Roshi, the abbot, walking slowly to the open door and spreading the Dharma through the world. This is Reality.

Breakfast at 6 a.m: rice gruel, two salt plums, a piece of pickled radish, and hot water to drink. Then an hour spent on indoor cleaning. I was responsible for the founder‘s shrine, where I did my meditation. It was set at right angles to the Zendo, and I could see the head monk, and hear his clappers and bell. They were signals for the beginning and end of chanting and meditation periods.

Then came communal outdoor work for the monks, which of course I could not join in, but I found a neglected part of the old graveyard and kept it swept and weeded.

At 10 o’clock was scripture reading for an hour. By a happy coincidence, the scripture for that term was Hui Neng’s Platform Sutra. I had brought only three books with me, and one of them was Hui Neng. (The other two were Suzuki’s Manual of Zen, which contains the chants for the morning ceremony, and a Japanese dictionary.)

The scriptures are not read, but are chanted for an hour. Japanese is a syllabic language, so anything can be chanted. On the first day, I knelt on the floor in formal position and listened. Roshi shouted at me, ‘Why you so lazy? Why you not chant scripture?’ He was always very rude to me, or else I was ignored as completely as a speck of dust on the ground. Until I got used to it, I felt very miserable. It hurt every time, but eventually I accepted it. I thought ‘I’m here to learn, and I am learning. It is so very kind of him to have me here at all. Why should I be unhappy just because he seems to dislike me so much?’

Anyway, this time I got out my Hui-Neng and obediently started chanting in English, and you really couldn’t imagine anything so funny in your life. In this beautiful hall, rows of yellow-faced shaven-headed monks solemnly chanting in Japanese, their black robes making beautiful flowing shapes against the translucent rice-paper windows; and there, right at the end of the very last row, a white woman in a Western cotton dress, equally solemnly chanting: ‘Learned- au-di-ence-your-own-Mindis- the-Bud-dha-All-of-you-are-the-o-ri-gi-nal-Mind-which-produ-ces-all-things . . .’

At first it seemed a silly way to read the scriptures, but later on it began to make sense. The syllables just roll on and on. We are not meditating on them, but on the koan. Suddenly one comes across a sentence that completely integrates with the meditation, and the whole thing lights up like a flash.

The main meal of the day is at 11a.m., and we take our chopsticks and set of bowls in with us. The five black lacquer bowls fit neatly inside each other, and are easily carried in the pockets of the long flowing sleeves. There is a good thick vegetable soup made with plenty of soya flour and rice, a vegetable, pickled radish and tea. The meal is strictly silent, and the food is served beautifully. Two monks enter carrying heavy wooden rice tubs high over their heads. With a graceful movement they dip right down to the ground in front of Roshi and the chief monks. They are seated on the floor of course, so it is a long way down. Then the monks get right up again and down in front of the next monks, and so on right down to me at the far end.

I shall never forget one day when the monk with the great tub swooped down in front of me. And instead of mounds of beautiful white rice and a ladle; to my horror I saw piles of long, long slippery noodles and a pair of serving chop-sticks as large as pokers. I knew perfectly well that I could not handle that situation gracefully, so – no lunch. I bowed politely, indicating that I did not want any, thank you. But they all realized why, and a great roar of laughter went right round the silent room, Roshi included. The serving monk, grinning from ear to ear, picked up the giant chopsticks, and filled my bowl to over-flowing.

Anyway, when the food is all served and getting cold, we chant for about ten minutes: the Heart Sutra, invocations to Vairocana, Shakyamuni, Maitreya, Manjusri, Samantabhadra, Avalokita, Prana, and to all other Buddhas and bodhisattvas in the ten directions and the three periods of time. Then come the Five Reflections:

First, let us reflect on our own work. Let us see whence this comes.

Second, let us reflect how imperfect our virtue is, whether we deserve this offering.

Third what is most essential is to hold our minds in control and be detached from greed, hatred, delusion.

Fourth, that this is taken as medicinal and is to keep our bodies in good health.

Fifth, in order to accomplish the task of Enlightenment, we accept this food.

Next, the first three mouthfuls of food are dedicated:

The first morsel is to destroy all evil;

The second morsel is to practise all good deeds,

The third morsel is to save all living beings,

so that we all attain Buddhahood.

After that, we may eat. There is plenty of food, and the hungry young monks have their bowls refilled several times. I never take an extra serving because all my muscles are so aching and exhausted that my fingers are clumsy. We all finish together, taking our last mouthful of rice at the same moment that Roshi takes his. [He, too, takes only one serving, but he eats slowly so that the youngsters have time to eat as much as they need.] Then the tea comes round, and you hold up your largest bowl, the one that is still soupy. You do not drink it yet. Picking up the piece of pickled radish in your chop-sticks, you clean the smaller bowls and wash them up in the tea. Then you drink the tea and stack the bowls back inside each other – washing-up done. The whole thing is performed silently, like a ritual ballet. The koan is held in mind, and again, nothing but sheer beauty. Then comes the last little verse to be chanted before we all file off:

Having finished the rice-meal, my bodily strength is fully restored.

My power extends over the ten quarters and through the three periods of time, and I am strong.

As to reversing the Wheel of cause and effect, no thought is to be wasted on it.

May all beings attain miraculous powers.

After lunch is rest for one-and-a-half hours. Indescribable bliss, but of course there is still the koan. But when you are lying down comfortably it seems quite a different experience! There is communal work until 3 p.m; then a sermon, or teisho.

Zen masters do not preach from a pulpit. They sit at the end of the hall facing a statue of the Buddha and offer the Buddha their own understanding of the truth. It is their sanzen direct to the Buddha. The monks are allowed to be present and listen, but through their koan meditation, not thinking about it with the logical mind. Traditionally, during teisho, flashes of truth fly up like water in a fountain, and everyone receives at least a spark of insight.

Zen Master Rinzai once gave this short sermon:

‘There is one true man with no name who presides over your body of red flesh. He is all the time coming in and going out through your sense organs. You who have not yet experienced this, look, look.’

A monk came forward and asked:

‘Who is this true man with no name!’

Rinzai came down from his chair, took hold of the monk and said:

‘Speak! Speak!’ The monk hesitated, whereat the master let go of him saying: ‘What a worthless piece of stick is this true man with no name!’ and returned to his own quarters.

After this, there is meditation for an hour till the medicinal meal at 4 p.m. In hot climates where Buddhism originated the monks never eat after midday. But in cold countries, and especially where the monks do hard physical labour, more is necessary. Nothing is cooked specially for this meal, but if anything is left over from lunch, it is heated up. (Naturally, the cooks see that there is something left over!) And no chanting because it is not a real meal, only heated-up left-over rice and vegetables, the inevitable pickled radish, and hot water to wash the bowls with and drink afterwards. If local farmers have anything they cannot sell, they give it to the monastery. Once someone gave us a load of cabbages. For a whole week we ate cabbage for lunch, with cabbage soup, and then, at 4 o’clock, – heated-up cabbage.

Afterwards comes rest for three-quarters of an hour while the monks take their turn in the o-furo. The o-furo, or bath, is an astonishing thing, like a great old-fashioned metal copper pot, heated by a wood fire underneath that is fed from outside the bath-house. It has room for four people to soak at a time. Naturally you cannot touch the hot metal itself, but there is a wooden raft floating on top, and slowly you develop the art of standing on it, so that it sinks under you. Then you can soak in almost scalding hot water up to the chin. If you are clumsy, the raft tips, and you get blistered on red-hot metal. (You only really appreciate that nearly boiling water when your muscles are almost at screaming point during sesshin.)

Anyway, someone bangs the wooden clappers every few minutes. At the first clappers, four monks go in and prostrate themselves three times in front of a statue of a sage who got enlightened in a hot bath. Then they undress. At the next clappers, they go down to the stone floor and soap themselves clean, rinsing off with buckets of water, while four more come in to the undressing part. At the next clappers, the first four get into that strange tub full of clean, scalding-hot water, while the other fours move on. At the next clappers: the soakers get out and dress to make room for the next four, and so on. There can be sixteen monks there, in various stages.

These monastic rules were set down by Master Po-Chang in China, over a thousand years ago, and naturally there is nothing in them about a Western woman needing a bath. So there is no possibility during the monastic routine. However, late every evening, the dear kind monk in charge of o-furo went and lit the fire and heated up the water again. ‘Daw-san, o-furo.’

Of course, it was the same water that all the monks had used earlier. And although the principle is that the water is perfectly clean, because everyone rinses carefully before getting into it; nevertheless, it was rather a peculiar colour, and I always wondered about a small fishing net hung handily beside it. Never mind, I had a beautifully hot bath every night and a very warm heart inside me for the kindness of that monk and his extra work.

For three hours every evening, there was further meditation. The big teapot came round, this time with real Japanese green tea, and a small cake with bean-paste in it. This was the sugar intake for the day. At 9 p.m. was the closing ceremony and then bed.

There was three weeks of this until the next sesshin week, by which time I felt like a seasoned campaigner. Now it was a familiar struggle, a battle to be entered joyously, for all its hardships. One had learned little tricks, such as a few dry tea-leaves hidden in a pocket. Chewing them during a break is a great help.

The weeks flowed past until I had been there nearly two months. I was always dirt underfoot, and the least and lowest tagging on the end of the line, and there was always pain. But the koan training went on, and there was a singing in my heart.

One day the monks were cutting trees for a new building. They were very tired, and that night Roshi announced: ‘Hard work today. Halfhour oversleep in morning.’ Laughing, he looked over his shoulder at me. ‘You not deserve over-sleep. You not work.’

I thought ‘Do I take that as a joke or not? – Better not.’

So, in the pitch dark next morning, I went to my place, ready to sit there for half-an-hour’s meditation before the get-up bell. Hardly had I settled down on the cushion, than along came Roshi. ‘Ah, you up early! – Come for walk.’

That early-morning walk was a gift that will always be with me. Up through the forest to the ridge of the hill, sunrise over Mount Fuji with a friendly Roshi – at last I was really accepted. What would I have missed if I’d stayed in bed that extra half-hour!

At last, Roshi was prepared to give me individual teaching, but the monastic rules were laid down a thousand years ago. There is literally no time or opportunity in a monastery to teach a woman who cannot even understand Japanese. So – bless his heart – they say a roshi treats his pupils with grandmotherly kindness, and it is TRUE. For the rest of my stay he got up half an hour earlier every day, just to help me.

He had been lovingly kind to me when he was being cruel, and now he was being lovingly kind to me with all his laughing companionship. It was all the same to him: the means towards the Enlightenment of all living beings must be as skilful as possible, and I happened to be the one needing help at this very moment.