EIGHT

Taggie was a very easy baby. In fact, had he not been my first child, I think I might have worried because he so rarely cried. You could do almost anything with him, take him anywhere, and he didn't complain unless he was hungry. He would go right back to sleep after I fed him or rest passively in his crib. Later, when we discovered that he had so many problems, I wished I had known what to look for earlier.

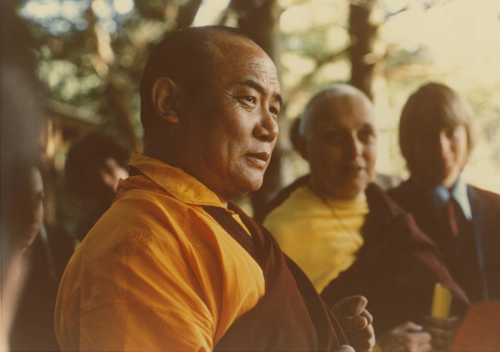

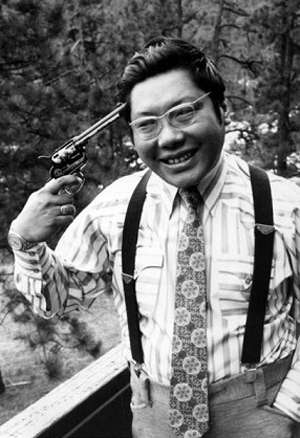

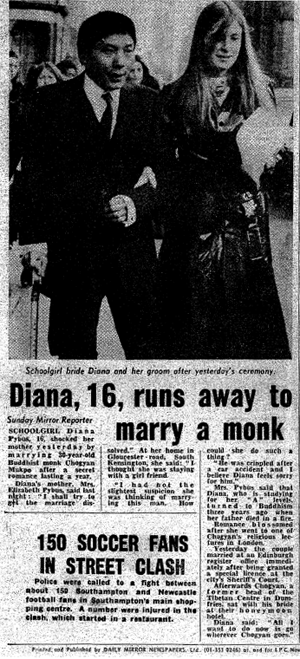

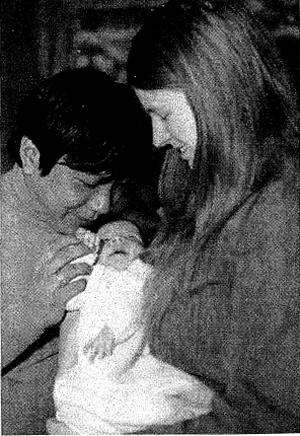

When the baby was around two months old, in May of 1971, we all went to California together. We visited Suzuki Roshi again, this time at San Francisco Zen Center on Page Street. We had tea with Roshi and his wife Okusan in the garden as SFZC, and Roshi did a special ceremony for Taggie. He bestowed on him the Japanese name Toronoko-san, which means "tiger cub" in Japanese. During our second visit to California, we also met Alan Watts, and Rinpoche gave a seminar on Alan's houseboat in Sausalito. Alan had converted part of the boat into a shrine hall where his students came to meditate. He would sit up in front in brown robes while people chanted, and then he would give his talk. The scene there felt strange to me, somewhat of a Westerner's kooky approach to Buddhism. Rinpoche, however, was quite fond of Alan and appreciated him for having laid the ground for the further introduction of Buddhism in America by popularizing Zen during the sixties.

John Baker came on the trip to California with us. One day John was driving us somewhere in Oakland, and he said to Rinpoche, "Could you tell me something about mindfulness in the Hinayana?" He said that right as he drove through a red light, and we had a car accident. Rinpoche ended up with a few broken ribs, but fortunately no one was seriously hurt.

When we left the Bay Area, we drove down the coast to spend several days at Tassajara, where we had had such a lovely visit with Roshi the year before. While we were there, Rinpoche received a letter, hand delivered by one of his students, from His Holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa, the head of Rinpoche's lineage. His Holiness said that he had recognized Taggie as a tulku, the reincarnation of one of his own teachers, Surmang Tenga Rinpoche. The night the letter arrived, Taggie cried all night, which was very, very unusual for him.

It was a great honor that our child was being recognized as an important Buddhist teacher. This announcement signaled some measure of acceptance from the head of the lineage -- who had not been especially happy when Rinpoche gave up his robes and married me. Still, we knew that this appointment would bring with it a heavy burden of expectation from the Tibetan hierarchy. Earlier, I described Rinpoche's education and upbringing in Tibet. This was the normally accepted pattern for raising a young tulku. Although everything in Tibet had been disrupted by the Chinese occupation, many of the Tibetan teachers who succeeded in escaping were establishing monasteries in India and other countries bordering Tibet. As much as they could, they were reinstating the traditional approach to educating young lamas. In fact, His Holiness Karmapa had established his monastery in Sikkim and was training many young teachers there. There would be pressure on Rinpoche and me to send Taggie over to be educated, as soon as he was old enough to go. The Tibetans believe that if a tulku is not recognized, enthroned, and properly educated, he will develop mental illness, a kind of tulku's disease, because he is not fulfilling the role that is intended for him and for which he presumably came back and took rebirth.

Rinpoche didn't want to send Taggie back to India for training. Because he felt so strongly that the future of Buddhism lay in the West, he thought it would be better if his children were educated here. From his own experience at Oxford, he had tremendous respect and appreciation for the Western educational system. He also didn't want to recreate the loneliness of his monastic childhood for his own children. As well, he wanted to play a personal role in their upbringing, not only as the children's father, but by providing whatever spiritual guidance his children might need. So he wanted Taggie to remain with us. Then, at a later date his son could receive further training in Asia. As Taggie's mother, naturally wanted him to stay at home with us. With all of these issues and feelings, it's no wonder that Taggie cried all night after we received the letter!

From Tassajara, we continued down the coast to Los Angeles, where Rinpoche taught a seminar entitled the "Battle of Ego." He began to attract committed students in L.A. We spent time with Baird Bryant and Johanna Demetrakas, two filmmakers with whom Rinpoche made a close connection. Rinpoche was in the early stages of making a film about the life of Milarepa, in which he wanted to try out an approach to filmmaking that involved applying concepts from the tantric or Vajrayana school of Buddhism in which he was trained. He was interested in applying a tantric framework called the Five Buddha Families to making a film.

The Five Buddha Families -- buddha, vajra, karma, padma, and ratna -- refer to five distinct styles of both enlightened and confused behavior. Each "family" has both a sane and a neurotic manifestation. I During the early seventies, Rinpoche used this paradigm in much of his work, not only as it applied to art but also in understanding human psychology. In terms of filmmaking, he felt that how a scene is shot can capture or convey the energy of any of the five families. The camera could look at the same situation from five different angles and convey five different interpretations or insights. The idea of working with the qualities of the buddha families in their art was intriguing to Johanna and Baird, as it was to many other artists Rinpoche would meet.

In 1973 Johanna and Baird would travel with Rinpoche to Stockholm, Sweden, to film some magnificent thangkas of Milarepa's life housed in ,the Museum Ethnographia. He intended to use the footage of these thangkas in his film, but because of a problem with the camera lens, the footage they shot was out of focus, and largely due to this obstacle, the movie was never completed.

While we were in Los Angeles, we were invited to have dinner with Krishna and Narayana at the Integral Yoga Institute, or the IYI as they called it which was Swami Satchidananda's center. Rinpoche was excited about going to the IYI for dinner because he liked Indian food so much. They served us an excellent Indian vegetarian meal. After meeting Krishna and Narayana in Boulder earlier that year, Rinpoche had become interested in getting to know them, better, particularly Narayana. Narayana came to dinner in a red velvet shirt. I was impressed by his charisma. He was warm and outgoing and seemed quite intelligent. Shortly after our visit, Narayana and his girlfriend, Lila, along with Krishna and his new girlfriend, Helen, joined our community. Rinpoche asked them to move to Tail of the Tiger, which they did that summer. On their way there, they drove through New York to get Swamiji's blessing, which was freely given, and headed on up to Tail. They got a house in Kirby, Vermont, where they started the Trikaya Bakery. Lila was pregnant at the time with their first child. She and Narayana were married at Tail.

Now that I had the responsibilities of motherhood, I stayed home more of the time when Rinpoche traveled. Over the next few years, he crisscrossed America I don't know how many times. I can't count the number of days a year he was on the road traveling and teaching. When he was in Boulder, there was still a beehive of activity at the Four Mile Canyon house. In spite of the chaos that was a feature of our lives, this was a truly magical time in my life and marriage with Rinpoche. We were very close during these years. It was a time full of hope and promise, and I remember this as a particularly happy chapter in our life together.

There was something energizing about the chaos, in fact. Rinpoche was so expansive in its midst, and we had a lot of fun together during this era. In spite of all the people around all the time, it was quite intimate in a way. The community was still small, relatively speaking, and I rather liked it that so much occurred at our house. I enjoyed having Rinpoche at home a lot, even though he brought so much activity in his wake. I could always go to bed when I got sick of it. There were obvious frustrations -- the house was a mess and we had almost no privacy -- but it was a very relaxed time. I was experiencing my own sense of exhilaration and relief that I'd gotten out of the English situation and away from my mother. I was riding on the freedom high and the fact that I had this wonderful relationship, a wonderful life. Having a child was also fulfilling for me. We had left behind the black era completely. I couldn't imagine my life being any other way.

In tantric Buddhism, there is a whole pantheon of deities that practitioners visualize as part of their meditation practice. Some of these have a rather normal anthropomorphic form: two arms and legs, one head, two eyes, two ears, and so forth. However, some of the Vajrayana deities have multiple arms and legs, a number of heads, and many eyes that see in all directions. This is connected with the accomplishment of compassion or the bodhisattva's skillful means. Avalokiteshvara, for example, the buddha of compassion, is sometimes depicted as having a thousand arms and a thousand eyes, to convey his untiring and remarkable efforts to alleviate the suffering of beings. Beginning in this era, Rinpoche seemed to take on this quality of all-accomplishing, all-seeing superhuman activity. The multifaceted way he worked with people was remarkable. He seemed to have hundreds of conversations about all kinds' of things going on with all kinds of people all the time. If I tried to describe all of these relationships to you or tried to tell you about everything he was doing, even in one month, it would take up hundreds of pages. At the same time, being with him, it often seemed as though nothing was happening. There was a way in which he was absolutely open and spacious in the midst of all of this activity; and you never felt that he was distracted when he was with you. When he was talking to you, you always felt that you had his complete attention. I think that is one reason that I was able to tolerate the chaos and all these people so intimately involved in our life. I didn't feel that they were stealing him away from me. He was very much there for me, when he was there!

On the other hand, we both began to acknowledge that if we wanted to have time alone together, it was not going to happen at our house in Boulder or on his teaching tours. So we began to take vacations, or holidays, as Rinpoche preferred to call them, which was time set aside for the family. Occasionally, someone would come along to help out, but in the early days, it would just be Rinpoche, me, and our child, or our children, as it became quite soon.

The first vacation I can remember us taking was to New Mexico in 1971 when Taggie was an infant. I now had a driver's license and I drove the three of us to Santa Fe. On the way down, we spent the night somewhere in the mountains of southern Colorado in a motel. We went to a cowboy cafe for breakfast, and Rinpoche wore his Stetson hat. Then we drove on into New Mexico. We had rented a. small trailer, which was located in the landlord's backyard behind the main house. Rinpoche helped out a lot with Taggie while we were there. He used to put Taggie in bed with us, and he was very sweet with him. He would watch him when I had a bath and call me if he cried. One time, I left Rinpoche alone with Taggie to go to the grocery store, and he figured out how to change diapers with one hand, but he got irritated that Taggie would squirm. Rinpoche also tried out his theories of insect control in New Mexico. He didn't want to kill the ants that invaded our trailer, so he put little lines of Ajax cleanser in front of the glasses and the plates, because he thought the ants wouldn't cross the Ajax. Actually, it did work.

We liked to walk around the plaza in downtown Santa Fe and look at the things for sale. Most of the vendors were Native Americans who had pottery, jewelry, and other items laid out on blankets or a table on the wide sidewalks along the sides of the square. Rinpoche bought me some silver and turquoise jewelry while we were there. He commented that the Native Americans looked a lot like Tibetans, and we talked about the magic in the Native American culture and his appreciation for that. We visited a number of pueblos in the surrounding area during our visit.

We both loved the spicy Mexican food in Santa Fe. One night we wanted to eat in an expensive restaurant in Santa Fe, which was still something quite rare for us because we didn't have very much money. Rinpoche insisted that we splurge. We dressed nicely and made a late reservation for a romantic dinner. The restaurant was completely done up in red velvet, and it seemed to be a very exclusive place, a place of fine dining. We were served an elegant meal, and everything was beautifully presented. In the middle of the meal, Rinpoche picked up his baked potato in his hand and bit into it. I said, "What are you doing? This is really, really embarrassing." He replied offhandedly, "Oh, Prince Philip would do something like this."

Altogether, he felt very connected with the land in the Santa Fe area and the Native American traditions. We enjoyed ourselves immensely, and we planned to return the next year. On the drive home, Rinpoche commented that we should have named our first son "Gesar," after the Tibetan warrior king. I told him not to worry, that we could give that name to our next son.

After we got back to Boulder, Rinpoche took off on another teaching tour, and I was left at home. John Baker went with Rinpoche, and Marvin Casper was away somewhere else. At this time, P.D., another senior student, was also staying in the house with us. While Rinpoche was away, P.D. started to lose touch with reality and ultimately had a psychotic episode, which I had to deal with on my own.

When the two of us went to the supermarket together, P.D. picked out a huge raw ham and an industrial-sized package of coffee filters. Nobody in the household drank coffee, so I found this odd, but I didn't think too much about it. That night, after I went to bed, P.D. came into my bedroom in a manic state. I felt threatened by his tone of voice and his erratic movements and comments. I had the baby and I didn't want him in my room, so I got him to leave, and then I put the dresser in front of my bedroom door. He banged on the door for a while and tried to push his way in. This went on for a few nights. Every night he would try to break into the bedroom, and I kept myself barricaded in. Then, one morning when I got up and moved the dresser, I looked around the house but P.D. was nowhere around. I got the baby up and dressed to go out shopping. When I went out to the car, I found P.D. walking naked down the road in front of our house at Four Mile Canyon. I convinced him to come back inside and get some clothes on.

At that point, I phoned Rinpoche and told him that we had to deal with this issue as soon as possible. The night that Rinpoche got home, there was a party at the house to welcome him back. As always, a lot of people showed up to hang out with Rinpoche. During the evening, P.D.'s behavior disintegrated, and it was obvious that he "needed help. After observing him for a while, Rinpoche said, "I think we have to take him down to the hospital." So John Baker took our disturbed friend in one car, and I drove Rinpoche in the other. We went down the canyon to Boulder Memorial Hospital at the end of Mapleton Avenue. At this point, it was about two in the morning.

P.D. and John Baker had arrived ahead of us, and we joined them in the waiting room. The psychiatrist on duty came over to where we were all sitting, and before anyone could say anything, P.D. announced, "Here is Mr. Mukpo. I've come to commit him." Rinpoche replied, "Actually, P.D., I've come to commit you." Confusion ensued, with P.D. insisting that Rinpoche was the prospective patient. Finally, the psychiatrist said, "I want everybody to be quiet. I'm going to ask a third party who has come to commit whom." Shortly thereafter" P.D. was admitted to the hospital. There were a lot of wild times, but this one stands out for me because I had to deal with much of the situation alone. To me, it signified how vulnerable and somewhat abandoned I felt at times when Rinpoche was away.

Later I encountered Kunga repeatedly, and we became friends. He continued to teach, and in 1971 Rinpoche told me to start teaching as well. But Kunga was the star. Until one day when he had been in San Francisco teaching, we received word that he had had a mental breakdown of some sort. The report was that he had tried to have sex inappropriately with a woman, had somehow gotten himself stabbed in the leg by someone unnamed, had been running down streets naked, and more. Rinpoche sent some students to San Francisco to bring him back, which they did. At that time Marvin Casper and I were living with Rinpoche in a house just outside Boulder, Colorado in Four-Mile Canyon. It was to this house that Kunga was transported, and for a few weeks I watched and participated as Rinpoche worked with Kunga. Eventually, he was committed for a few weeks to Boulder Psychiatric Institute. After that he calmed down and, more or less, recovered, but never again did he hold the position of prominence he had prior to his “break.”

-- My Love for Kunga Dawa [Richard Arthure], by John Baker

That summer, we went to Allen's Park, which is a small town near Rocky Mountain National Park, about an hour north of Boulder. Rinpoche conducted a major seminar there on the six states of bardo, teachings connected with the Tibetan Book of the Dead. We stayed in a small log cabin next to the main lodge at the conference facility in Allen's Park, and Rinpoche taught in an outdoor tent. By now, there were around three hundred students attending his major seminars in Colorado. The tent was packed.

Rinpoche explained to me that his lineage and his monastery in Tibet were particularly associated with practicing and propagating the bardo teachings, and during 1971 he gave three seminars on material related to this. Although he had people practicing a basic form of sitting meditation, his lectures in these early years imparted some of the most advanced teachings from his lineage. I think that most of us understood about 2 percent of what he was presenting at that time. Some of the material was incorporated over the next few years into the study material for students interested in Buddhist psychology, and some of it was used in Rinpoche's commentary on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which he translated with Francesca Fremantle. However, a great deal of it was simply being planted in people's subconscious, I think, so that much later they would come back to these lectures and begin to unravel the profundity of what he was presenting. After he died, the talks from this program were incorporated in a posthumous book, Transcending Madness: The Experience of the Six Bardos, edited by one of his senior students and primary editors, Judith Lief.

At the end of the summer, we went out to Tail for a month. We rented a house near Harvey's Lake, a five-minute drive from Tail of the Tiger, and Francesca Fremantle stayed there with us. Rinpoche taught a seminar entitled "Work, Sex, and Money," and then he gave another lecture series on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which he and Francesca were just starting to translate. She edited much of the material from his talks at Tail for the commentary in that book.

There was a huge group scene at Tail, but at the house we could get away from it and have time together as a family. Rinpoche was drinking a lot at the talks. One would have to say that his drinking was a regular feature of our lives. At that time, I didn't see it as a problem. Had Rinpoche remained in Tibet or the Tibetan diaspora in India, the ground would have been laid for him to present the Buddhist teachings. There was a traditional format there and a basic understanding to accommodate whatever he might want to present. Instead, he struck out into completely foreign territory. I feel that in presenting the Buddhist teachings in the West, alcohol was one of the vehicles that he employed. He told me that it helped to ground him and allowed him to communicate. Without it, I don't know if he would have taught with such outrageous directness and expansiveness. In tantric Buddhism, amrita, or blessed alcohol, represents turning poison into nectar or inspiration. It is the idea that you do not reject any situation or state of mind in your life, but you use the most extreme or negative things as fuel to transform the ignorance of ego into wakefulness. I think Rinpoche did use his drinking in that way, which I know is a controversial thing to say.2 On the other hand, I certainly acknowledge that, over time, alcohol was very destructive to his body. But that was not a question at that time, and in those days I didn't have an issue with his drinking.

And there is the drinking. We all know about alcohol because we use so much of it. Rinpoche drinks to the point where it is obvious to the community. It has figured in several incidents.

"Alcohol is the drug of choice at Naropa," said the Village Voice in an article on the school last fall. "With Alcohol, Rinpoche has said, you relate to the earth." And the Voice added "Or at least the linoleum around the toilet bowl."

We have arrived at a native intelligence about alcohol. We know that it contains a false wisdom.

-- The Great Naropa Poetry Wars, With a Copious Collection of Germane Documents Assembled by the Author, by Tom Clark

I was often Rinpoche's chauffeur to and from his talks. One night, he was quite drunk by the time we got into the car at Tail to come home. I parked in front by the house at Harvey's Lake, and he opened his door, stepped out, and just disappeared. When I got out, I realized that I had parked right next to a ditch on the property. Rinpoche was completely relaxed because of how much he had drunk, so luckily he was uninjured. I helped him scramble out of the ditch.

Another time at Harvey's Lake, one night after dinner, he drank until he sort of passed out on the hardwood floor in the living room. I didn't want to leave him there for the night, and I didn't want to sleep by myself, so I tried to figure out how to get him to bed. I found a large Indian blanket, I rolled him onto it, and I dragged him on the blanket down the hardwood corridor. He was quite heavy, so this wasn't all that easy to do. When I got to the bedroom, just when I was trying to figure out how to get him from the blanket to the bed, he started laughing, got up, and walked really fast back into the living room, where he lay back down and appeared to pass out again.

We often ate with people at Tail, but sometimes we would have a family dinner at the house. Rinpoche always liked meat for dinner. One night I worked really hard preparing a leg of lamb. He got impatient waiting for dinner to be served, and he said to me, "This is ridiculous. This whole cooking and eating thing doesn't make sense. You spend so much time cooking dinner, when it takes so little time to, eat it." I went out into the garden to pick some vegetables to go with dinner. When I came back, the leg of lamb -- which had been sitting on the table ready to carve -- had bite marks where big chunks of meat had been taken out of it. Rinpoche had just picked it up and eaten his dinner off the bone.

That summer, we spent time with Narayana, Lila, Krishna, and Helen at their house in Kirby, just outside of Barnet. Lila went into labor in September while we were staying at Harvey's Lake, and we went over to the house to witness the birth. Narayana was going to deliver the baby himself, but Lila had a terrible labor and ended up being driven to the hospital in St. Johnsbury, where she gave birth to their son Vajra. After that, Lila and I used to spend time together with our children. Rinpoche did a child blessing ceremony at Tail, and I remember Lila bringing Vajra to be blessed when he was just a tiny baby.

That fall when we left Vermont, I went with Taggie to England to visit Osel at the Pestalozzi Village. We were still waiting for the home visit from the Social Services people in Boulder. We didn't seem to be able to speed things up at all, which was quite frustrating. While I was in England, Rinpoche traveled to Canada to teach. I believe it was the first time he'd been back since arriving in the United States. He was scheduled to give seminars in both Montreal and Toronto. He kept phoning me in England to ask about Osel and to say how much he missed me. In Toronto, he gave a seminar at the home of one of his students, Beverly Webster, a very elegant woman who later became his executive secretary. While he was there, he met with Kalu Rinpoche, a venerable Tibetan teacher then in his mid-sixties, whom Rinpoche admired very much.

Suzuki Roshi had been quite ill and jaundiced that fall, but the cause, of his symptoms had not been diagnosed. Rinpoche always wanted to have news of what was happening with Roshi. One of Rinpoche's close students at this time, Bob Halpern, had been a student at San Francisco Zen Center for a long time before he joined us in Boulder. Bob went with Rinpoche on the trip to Canada, and Fran and Kesang also traveled with him. The night that Kalu Rinpoche visited, after he left, Kesang came to Rinpoche with the news that Roshi had been diagnosed with liver cancer, which was a terminal condition.

Before she finished telling him the news, he started weeping. Later, Bob told me that Rinpoche was screaming in agony, as though he were in the midst of death throes. Bob said that his tears actually turned red with blood, which fell on Beverly's snow-white carpet. After a long time, when he finally stopped, he said to Bob, "Go out first thing in the morning. I'll be there in a few days." He had his last visit with Roshi at San Francisco Zen Center a short time before Roshi's death; Rinpoche returned there for Roshi's funeral in December. During the ceremony, he went up to offer a khata, a Tibetan ceremonial white scarf. With one hand, he unfurled the scarf and it hung in the air and then draped perfectly, beautifully, over the casket at the same time that he uttered a piercing cry. After the funeral, he was asked to give a talk to everyone assembled at the Zen center, and during his remarks, he broke down in tears. Some people said that it helped them to recognize and express their own grief.

Do you remember at the funeral? Well first all these honchos from Japan and America one after another with red robes - the vice abbot of Eiheiji or whatever went by his casket and [Trungpa] Rinpoche walked up heaving in agony with the Tibetan white scarf and kept trying to put the scarf on him and he wouldn't go and it kept flipping off the casket and he was heaving with emotion and Okusan broke into tears who had been so composed through the ceremony and afterwards she in a hurried way ran upstairs to get his walking stick that he'd last used and came down into the hallway and gave it to Rinpoche.

-- Interviews: Bob Halpern cuke page, Crooked Cucumber: The Life and Zen Teaching of Shunryu Suzuki, by David Chadwick

Rinpoche was so moved by Roshi's life and example and so saddened by his death. I believe that it spurred him on to implement the plans that they had made. He pushed forward the Maitri Project, which involved starting a therapeutic community for people with mental problems. Maitri means "loving kindness" in Sanskrit. The Maitri facility opened in Elizabethtown, New York, in the fall of 1973, and moved to land in Wingdale, New York, donated by Lex and Sheila Hixon in early 1974. The Naropa Institute, based on another of their joint inspirations, was inaugurated in the summer of 1974.

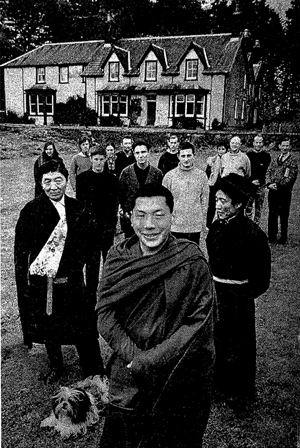

The end of 1971 was also an important time for another dharmic relationship in Rinpoche's life. In December, he spent another week at Tail teaching while I remained in Boulder. At that time, he met privately with Narayana and asked him to become his Vajra Regent and dharma heir, the primary inheritor of his spiritual lineage. In Rinpoche's tradition, the continuity of the teachings from one generation to the next is expressed through the teacher's handing down the oral teachings and the responsibility for maintaining the purity of the teachings to one or more dharma heirs. There is usually a primary dharma heir, as well as potentially many secondary heirs. In some situations, usually when a teacher has an established organization, he gives the position of regent to one student, who is expected to act on behalf of the teacher and the lineage after the teacher's death, until, in the case of many tulku lineages in Tibet, the teacher's next incarnation is old enough to assume his or her position. This idea of a regent who assumes power between one generation and the next has also been used in many monarchies, so regency is not purely an Asian concept.

For Rinpoche, it was extremely important to give the complete teachings of his lineage to a Westerner. In fact, I think he felt that he was giving many unique transmissions to his Western students, and he did not want them to feel that they were playing second fiddle to the Tibetans. So this appointment was a very important step. It showed that a Westerner could be trusted with the complete teachings and with the responsibility for the future of those teachings.

Rinpoche told Narayana to make plans to move to Boulder, so that Rinpoche could work closely with him, observing him and giving him proper training. Rinpoche had already told me that he was planning to do this. He often shared these kinds of plans and decisions with me. He would say, "This is a great person. I've brought him (or her) in. This is what he can do, and this is where we're going with it." Rinpoche asked Narayana to keep this future appointment secret for the time being. Rinpoche did not feel it was time yet to make this appointment public. With Rinpoche's permission, however, Narayana told his wife, his heart friend Krishna, and Helen. Indeed, this choice would have many implications for the future. I felt that Narayana was an excellent choice, although I didn't have Rinpoche's insight into his character. I thought he was quite charismatic and he had a special quality, a kind of intensity and brightness that were unique.

Our life was affected directly in another way by Rinpoche's visit to Tail that December. Another child came into our lives at this time. One of Rinpoche's students living on the East Coast, Eileen, was having serious psychological problems. She was a friend as well as a member of the sangha. She was so affected by her own psychological crisis that she couldn't care properly for her daughter Felicity, who was around seven. Felicity had been in a boarding school in New England, but she was very unhappy there. Eileen came to Tail of the Tiger with Felicity in tow when Rinpoche was there. She said that she couldn't handle her child any longer, and she was looking for someone to take her for a while. Rinpoche called and told me that he felt terrible about the situation. I suggested that we take Felicity, but he thought it would be too much for us to handle. Then Felicity gave Rinpoche a drawing she had made for him, and he was so touched by the gesture that he decided to bring her home with him. She joined our household for about a year.

During Taggie's first year, he was extremely uncomplicated. His motor development was quite advanced. He was sitting up and rolling over on his own at four months old. All the physical milestones were early, in fact. He was running around on his first birthday, in March 1972. However, I felt some concern when I talked with George Marshall, a student of Rinpoche's, when Taggie was fifteen months old. Adam, George's son, was the same age, and George told me how well Adam could talk. I thought to myself, "Oh, my child is a little slow in his speech development." Taggie did develop some speech, but often he just repeated what you said to him. He rarely vocalized anything on his own. He would repeat "doggie-dog" after me, for example, but he rarely would point at a dog and say, "doggie-dog" without prompting. However, he was my first child and I didn't know what to expect, so I didn't worry that much.

In the summer of 1972, Rinpoche and I went to Rocky Mountain Dharma Center for several weeks. It was to be the first time Rinpoche would teach a seminar there. For the summer, campgrounds were established for people attending the program, and a large tent was erected in a field, where Rinpoche would give his talks. I drove us up to "the Land," as we called it then. We had a Volkswagen Carmen Ghia at that time. As we were driving through the mountains, Rinpoche said to me, "Very soon we're going to be driving here in a Mercedes." I responded, "You know, you always have these terribly big plans." I wasn't convinced much would come of this. Sure enough, within a few years, we were driving to RMDC in a Mercedes, and Rinpoche reminded me about that conversation, as if to say, "See!"

As time progressed, our family finances became more stable. Rinpoche was able to take a salary for his work, and most of the time -- but not always -- he got paid. Our living situation remained modest for a number of years, and when we began to live in a more ostentatious way, it actually was not that we were spending huge amounts of money, but that we were using our rather modest mean~ and those of the organization to create an apparent manifestation of wealth. I am not saying that we remained terribly poor, by any means, but we were really living with what would be a comfortable middle-class income, most of the time. Sometimes, throughout our life together and up until the very end, there was no money and we were scrounging for the money to buy groceries. Most of the time, we were fine. On an inner -- nonmaterialistically based-level, Rinpoche was the wealthiest person I have ever known, but he wasn't the richest, in terms of financial assets. So, for example, when we got a Mercedes it was a used car. We never had a fleet of Mercedes or anything like that. We managed to keep up one slightly tattered vehicle for him at a time.

That summer we stayed in a little A-frame called Aloka, which means "light" in Sanskrit. Earlier that year, while we were at Tail, I had had a dream in which a being appeared to me and said, "Please give me a place in your body." I replied, "Yes, I will." While we were at RMDC, I conceived our second son, Gesar. He was the only one of my children who was planned, so to speak.

While I was pregnant with Gesar and we had both Taggie and Felicity at home with us, we received word that there would finally be a visit from Social Services in Boulder to establish whether we had a fit home for Osel. I had the house spotlessly clean when a man came to do the evaluation. He was a bit taken aback by how young I was, and when he saw that there were already two children in the home and that I was pregnant with a third, he questioned whether we could really handle another child. I was indignant. "Do my children look dirty? Do they look uncared for?" I guess that in the end we impressed him as being suitable parents for Osel, because not long after this we heard that Osel could come and live with us. Once again, Rinpoche's teaching schedule made it impossible for him to travel to England at the specified time, so once again I made the journey in the middle of a pregnancy to bring Osel home. This time, the outcome was as we had hoped. I picked him and his belongings up at the Pestalozzi Village, and we drove to London where we spent the night before flying to Denver.

To celebrate Osel's arrival and to help with his process of acclimatizing to family life and life in America altogether, Rinpoche and I decided to take another vacation to New Mexico before starting Osel in school. We decided to leave Felicity with friends in Boulder, and the four of us -- Rinpoche, Osel, Taggie, and I -- headed off to Santa Fe. For a few days, we stayed in the little trailer we'd had the year before, and then we moved in with Allen Ginsberg and a friend of his.

Just a few years ago, Osel -- who is now known as Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, the head of the Shambhala network of meditation centers -- shared with me jokingly how he felt as a child during this period. Apparently, when I told him we were going to take a family vacation alone, he was struck by anxiety. He thought to himself, "Oh no, nobody else is coming?" Rinpoche and I may have been somewhat overwhelming for him, and our unconventional, albeit cheerful, life was something he was not yet fully accustomed to. We thought it was so generous of us to take this trip, a great idea, at the time! He was probably relieved when we decided to stay with other people.

Allen Ginsberg suggested that we join him at David Padua's house, a friend in Santa Fe who had an adobe home near the Sangre de Cristo mountain range. Allen was staying there with his boyfriend Peter Orlovsky. During this vacation, it was pretty clear to me that Allen had a big crush on Rinpoche, and that he was a little jealous of me. When I went horseback riding with him one day, he made a number of sarcastic remarks that seemed out of place. I was surprised that he was mean to me. Allen probably imagined that, as Rinpoche's wife, I stood in the way of his having a relationship with the guru. Rinpoche was a beautiful young man at that time, just Allen's type. However, Rinpoche was not interested in men in that way. On the other hand, he and Allen had a lot to discuss in other areas. They were already making plans to launch a poetry school as part of the much bigger plans that Rinpoche had in mind for a Buddhist university.

Earlier that year, Allen had invited several poets to Boulder for a poetry reading. Gary Snyder, Robert Bly, and Nanao Sasaki were invited to read poetry with Allen Ginsberg and Rinpoche. In addition to his own poetry, Allen read some of Rinpoche's poems from a recently published book, Mudra, which included many of the early poems Rinpoche had written, in England in the sixties. The evening ended rather disastrously after Rinpoche put a large Japanese gong over his head while Robert Bly was reading a serious and significant poem. Rinpoche did a number of things to disrupt Bly's reading, actually. Gary Snyder and Robert Bly interpreted Rinpoche's behavior as rude and drunken. I guess it was, but from his point of view, their behavior was arrogant and bombastic, and he felt that humor was needed to lighten up the space. Allen took this controversy remarkably in stride, and managed to remain friends with all involved. Snyder and Bly, however, wanted nothing further to do with Rinpoche, and as far as I know, he had no regrets on his side.

Let us first briefly consider two prior episodes that occurred on the "Trungpa scene" in Boulder. They will help us understand Trungpa better.

The first was a benefit poetry reading for Trungpa's Karma Dzong Meditation Center, held at Macky Auditorium on the University of Colorado campus, May 6, 1972. Poets on hand included Ginsberg, Robert Bly, and Gary Snyder. Trungpa, acting as self-appointed emcee, was in his cups. During the reading, he upstaged the poets with his humorous antics, and at the end, he "apologized" for the poets in a muddled, patronizing speech ("I'm sure they don't mean what they said.") The evening ended with Trungpa drunk and truculent, yelling and beating on a big gong.

"If you think I'm doing this because I'm drunk," Trungpa told Ginsberg during the evening, "you're making a big mistake."

Ginsberg, already a great admirer of the young Tibetan master, was genuinely puzzled. "Is this just you," he asked, "or is this a traditional manner, or what?"

"I come from a long line of eccentric Buddhists," the eleventh Trungpa explained.

Ginsberg subsequently defended Trungpa for taking over the poetry reading.

But Gary Snyder, a longtime student of Zen, and Robert Bly, once a crazy-wisdom disciple at Samye-Ling, were offended by Trungpa's behavior -- Bly, as it was to turn out, quite seriously....

Unlike other Naropa faculty members, many Kerouac School poets have showed resentment when their paychecks were "loaned" back to the Institute without their having been asked.

In 1978, Ginsberg's pal, Gregory Corso, took out his resentment against the conservative Naropa administration by trashing his faculty apartment at the end of the summer session. This demonstration of Corso's own brand of crazy wisdom proved to be too much for the administration, which hasn't invited him back.

-- The Great Naropa Poetry Wars, With a Copious Collection of Germane Documents Assembled by the Author, by Tom Clark

Allen was an amazing human being in that way. As outrageous as he was and as much as he flaunted his sexuality and his politics, he was also a peacemaker and, except when he viewed me as a rival that one time, he was one of the most gentle, kind people I have ever known. It seemed to me that, sexual politics aside, he loved Rinpoche without hesitation, and as a student he was very devoted. He never seemed to doubt that what Rinpoche was doing was for the good of everyone involved -- even when it created difficulties for Allen in his relationships with other poets. He saw Rinpoche as a complete representative of the crazy wisdom lineage, and he took the crazy with the wisdom, with no questions asked.

While we were in New Mexico, Rinpoche killed a scorpion that we found in the boys' bedroom. It was the only time I ever saw Rinpoche kill anything. Rinpoche squashed it and flushed it down the sink. He felt badly about this, but he didn't want the boys to get bitten. While we were there, we also got our first big message that something was not right with Taggie. One morning, Taggie woke up early. He came and climbed into bed with me and put his hands on my chest. As I started to wake up, I saw that my chest was covered in blood. I soon realized that Taggie had cuts all over his hands. Somewhere in the. house, he had found pieces of broken glass and had been playing with them. I completely freaked out, but Rinpoche's response was very practical. He said that we should clean up his cuts and put socks on his hands. We did that, and he was okay. But it was very unsettling. Taggie's relationship with pain was never like a normal child's. A normal kid would cut himself once and cry, but Taggie kept playing with the glass. But we still weren't sure what it meant at this time.