When we got back to Boulder, we settled into a kind of routine, to the extent that our lives were ever routine, with me taking care of the three children in the household, and Rinpoche putting most of his time into teaching and the many other projects he had going. He lectured at the University of Colorado several times a week, and he traveled to both coasts to teach, as well as making side trips to many new places like Minneapolis and Topeka, Kansas. He also gave a number of seminars in Boulder over the next six months, and he had special meetings and led workshops for people involved in psychology, film, and theater. In the spring of 1973, he and his students in Boulder were going to host a seminar on the Milarepa film project, as well as two other week-long conferences, one on the Maitri approach to psychology (involving the Five Buddha Families and other concepts) and a ten-day conference sponsored by the Mudra theater group, which was working with exercises that Rinpoche was developing out of his own experiences with monastic dance in Tibet. The theater conference was being partially funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, which Jean-Claude van Itallie had obtained. He invited a number of prominent theater people to the conference in Boulder, including Robert Wilson, the eminent American artist and playwright, and his group of actors, as well as many others. There was a tremendous amount of work to prepare for all of this. And these are just a few highlights of what Rinpoche was doing at this time, just the tip of the-iceberg.

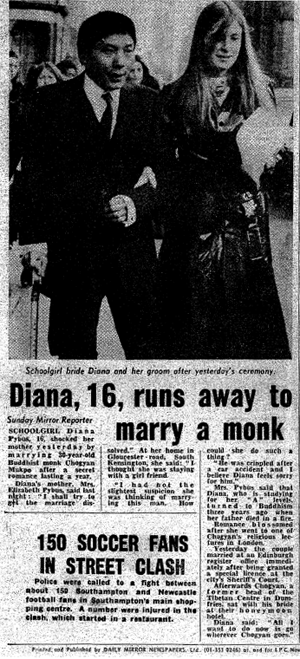

Rinpoche was incorporating facets of the Tibetan Vajrayana tradition into his presentation of secular disciplines such as film, theater, and psychology; later he would expand into many other areas as well. This weaving together of the secular and the sacred was characteristic of how he taught. Even in Great Britain he had had this tendency. In the 1960s he had already recognized that he was going to work with both the secular and the spiritual as indivisible aspects of his teaching. In the diary that he kept at that time, he wrote:

There are many people who are more learned than I and more elevated in their wisdom. However, I have never made a separation between the spiritual and the worldly. If you understand the ultimate aspect of the dharma, this is the ultimate aspect of the world. And if you should cultivate the ultimate aspect of the world, this should be in harmony with the dharma. I am alone in presenting the tradition of thinking this way.3

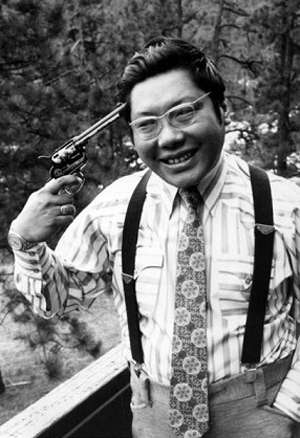

In December 1972, Rinpoche spent ten days in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, near Yellowstone National Park, teaching a seminar on crazy wisdom. Several of his students had bought a hotel there and were renovating it, planning to operate it as a tourist hotel called the Snow Lion Inn. In his seminar he presented an in-depth examination of the life of Padmasambhava and how his teachings and many manifestations were applicable to the present day as well as to the Tibetan medieval world of the eighth century. We all went to Tail of the Tiger for the Christmas holidays that year, where Rinpoche gave another crazy wisdom seminar. The teachings were magnificent, very much the heart's blood of his lineage. He had been waiting so long to present this material. After his death, these two seminars were edited into the book Crazy Wisdom.

Although I supported Rinpoche in whatever he felt he needed to do at this time, his lack of everyday involvement in our household was not ideal for our young family. When you have young children, I think almost everyone goes through a period that seems completely insane, and this was the era we were in during the early seventies, especially since we had so many children join our family so quickly. At this time, I was not even twenty years old. We didn't have much money for babysitters, and Rinpoche thought it was odd and somewhat degrading to hire people as domestic help. In Tibet, people served a teacher out of devotion rather than for money. It wasn't that Rinpoche was miserly, but he really felt that this kind of master-servant relationship was not healthy when it was purely a financial deal. He hoped that his students would help us out, and many of them did. I found, however, that by and large people didn't appreciate the difficulties of our domestic situation. Nevertheless, we made do as best we could.

Osel was trying to adjust to life in America and found school very challenging. Felicity was spaced out and often depressed and needing cheering up, and Taggie was becoming a real handful. I would get phone calls from the neighbors at five in the morning to tell me that Taggie was running around somewhere. While the rest of the household was still sleeping, Taggie would get out of his crib and go off for an adventure by himself in the neighborhood. One time, I found him playing on the roof of the garage of the Four Mile Canyon house. I remember trying to lure him away from the edge with jelly beans, holding them in my open palm and saying, "Candies, candies." Eventually I realized that I had to put an intercom in his room, and later I had to put a hook on the outside of the door. I felt terrible about locking him into his bedroom at night, but it seemed to be the only way to keep him safe. Once, when I was quite pregnant with Gesar, he slipped out of the house when I had taken my eyes off him for just a minute. I turned around and he was gone. He had on a little yellow, black, and red striped sweater, and I rushed frantically out of the house to see if I could spot him in the yard. Finally, I spied him in his bright-colored sweater across the highway halfway up a mountain. I had to climb the mountain in my pregnant state and carry him down. He was becoming difficult to care for.

Osel came into an already chaotic home situation, and in retrospect I feel that I was not a very good mother to him during these years. He was trying to adjust to America and to learn English, and on top of that, we found out later that he had a learning disability that exacerbated his problems. It took years to sort all of this out. When Osel was having trouble with math in school, for example, I would review his multiplication tables with him over and over. The next day, he would fail his math test, and I would become quite exasperated. He was incredibly shy, which made it more difficult for me to communicate with him. I was only nineteen at this point, and coping with three children -- each of whom had unique difficulties that needed attending to -- proved difficult. I was often frustrated.

Rinpoche was away a great deal of the time, and when he was in town he had so much going on that he was rarely home. There was still a lot of activity at the house, but in late 1971 we had acquired space for a meditation center in downtown Boulder, at 1111 Pearl Street, on what would later become the Boulder Mall. There was a meditation hall that could hold about a hundred people, several meeting rooms, and a suite of offices. Rinpoche gave the name Karma Dzong to the new center, which means "fortress of action," or it could also mean "fortress of the Karma Kagyu lineage." Rinpoche's students paid membership dues to cover the rent on this space. Although the hordes would still descend on the house from time to time, now much of the community activity was centered around Karma Dzong. So I was frequently home alone with the kids, even when Rinpoche was in town. Although this was a difficult adjustment, I also found that I enjoyed the space. I began to have more sense of my own life, apart from the scene that surrounded our life together.

However, I didn't have enough help with the children. Rinpoche and I talked about all this many times, and he tried to help find solutions. He continued to ask some of his students to provide assistance at the house. However, they were much more interested in being with him than in spending time with the children and me. Also, there weren't many people in our community at that time who had children. Rinpoche's students, many of them young people in their twenties, couldn't relate to what I was going through at all. There were a few mothers who were sympathetic, but they had their own families to care for. A few other people stepped forward and offered to help. However, sometimes, if I asked for someone's help, he or she would criticize me, saying that I should be doing a better job on my own. This didn't help the situation at all.

I wished that Rinpoche had more time for the family, and I think that he would have liked that too. He enjoyed those times that we were together as a family, on our vacations and such. But in general he was not that involved day to day. He had warned me this would be the case when we were first at Tail of the Tiger. Everything else came second to the dharma in his life. His mission, as I guess you might call it, was to bring the Buddhist teachings to America and to make sure that they flourished here, and he sacrificed much personal happiness for that. Unfortunately, his family suffered as well. On the other hand, he loved all of us tremendously, and he tried to be there for us as much as he could be. Whenever anyone in the family was having an acute problem, he would make time to attend to that. However, he couldn't do much to improve the overall quality of our family life during this era.

In the very early days, when we were still at Samye Ling, he once said to me, "I wish I were someone like Einstein." I asked him, "What do you mean?" He said, "Well, I wish I was one of those people who was so into something that I would get up in the morning and I would have a mission, something to do that was really driving me." Well, as they say, you should be careful what you wish for! He certainly became one of those people.

Luckily, with everything else that was going on, I had a very straightforward pregnancy with Gesar. I hardly had morning sickness or nausea throughout the pregnancy, which was good, because I didn't have time for it. By the time I was eight-and-a-half months pregnant, I was ready for this pregnancy to end. I wanted to get on with it. Hoping to induce labor, I went riding when I was enormous. When that didn't jump-start my labor, I came home and drank a glass of castor oil mixed in orange juice. (Somehow I knew that castor oil can cause contractions of the uterus.) Undoubtedly, it was an irresponsible thing to do. My water broke soon after that. I was admitted to Community Hospital in Boulder, and my doctor, Dr. Brown, was quite upset when I told him what I had done.

Although my water had broken, my labor didn't progress. They held me in the hospital, and after twenty-four hours, they began to administer Pitocin to induce labor. Dr. Brown had to leave unexpectedly, and I was left with another doctor. After I had contractions for twelve hours, he told me that he had surgery at 7 A.M., which was a few hours away, and that in hadn't had the baby by 5 A.M., he was going to do a C-section.

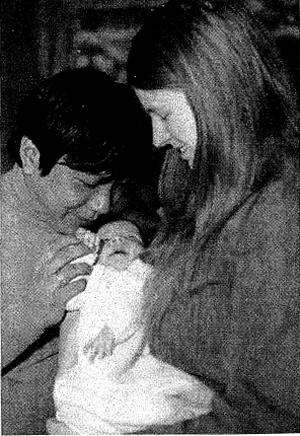

Quite a large group of sangha members was hanging out in Community Hospital, camped out in the waiting room, waiting for the child to be born. They were calculating the baby's astrological aspects while I was having contractions. Different people kept coming into my labor room, saying, "If you hold off just another half hour, the moon will be in the tenth house" and things like that. When Gesar was finally born, he was a triple Taurus. Rinpoche was with me the whole time. I was in an enormous amount of pain, the kind of pain where you don't know where the center or the focus of the pain is. They tried to give me a spinal injection of anesthesia, but it didn't work. The pain just kept going and going and going. Rinpoche was a fabulous labor coach, it turned out. He seemed . to know exactly how I was experiencing the pain, and he advised me on how to get through each contraction.

Gesar was finally born early in the morning on April 26. He came out with a full head of black hair and long fingernails. When they opened his mouth to suction him, I said to the doctor, "He has teeth!" The doctor said, "No, he doesn't have teeth." The doctor was fed up with me at that point because the whole thing had gone on forever. He said, "He doesn't have teeth. I've delivered thousands of babies, and babies aren't born with teeth." I started to have a panic attack, because I thought that if he had teeth, he might have a deformity. So I insisted, "No, he has teeth!" He said, "Listen, you need a cup of tea. You're English, and that will help. I'm going to show you the baby now, and the baby doesn't have teeth." Then he exclaimed, "Wait a minute. He's got teeth!" He had two pointed teeth that looked like fangs.

Gesar emerged as a strong personality in all respects. We gave him the name Gesar Tsewang· Arthur Mukpo. According to Rinpoche, King Gesar of Tibet was the first Mukpo, and he is regarded as a great warrior-protector of the Tibetan people. Tsewang means "lord of life." We added Arthur for King Arthur, another regal warrior king. Gesar was a little dynamo from the beginning. They removed his teeth in the hospital, because they were loose. Two months later he was teething again. He grew several teeth on the bottom, and they were also an odd set of teeth, so he was in the dentist's chair at two months old. Then, he didn't have center teeth on the bottom until his permanent teeth came in. The dentist put in a spacer to hold his back teeth· in the proper position and prevent them from filling in the front. As a toddler, Gesar used to bite other kids sometimes, and you could always tell if it was Gesar because you could see the mark of the spacer.

When Gesar was an infant, we were still living at Four Mile Canyon. When he was just a few days old and we were just back from the hospital, I put him in his bassinette and went to take a hot bath. Taggie came into the bathroom while I was in the tub, and I asked him, "How is Gesar?" And Taggie said, "Gesar is good. He's eating candies." I jumped out of the bath and ran into the other room. Taggie had stuffed lots of candies into Gesar's mouth, which I had to fish out. Another time, Taggie fed Gesar a container of blue shoe polish with a spoon. I became a rather frequent visitor to the emergency room.

As a baby, Gesar slept in the room with us. Rinpoche said that Tibetans would never have a separate bed for the baby, but I always thought we should have the baby in a bassinette or a crib. When Gesar was just a few days old, I put him to bed in his crib with a windup mobile. Whenever the mobile stopped moving, Gesar would start screaming. This continued until around two A.M., when Rinpoche insisted that we put him in bed with us. He said that if Gesar were in the middle, between us, he would be content and fall asleep. I told Rinpoche that I was afraid one of us would roll over on him in our sleep. Rinpoche said, "A father's instinct would never allow this." I gave in. About two hours later, I awoke to small muffled cries. In his sleep, Rinpoche had rolled on top of Gesar and was basically suffocating him. I started screaming to wake Rinpoche up, "Get off him! Get off him!" After that, if I put Gesar in bed with us, he slept on my side of the bed.

Gesar took to solid food very early, around three or four months old. At one point, I told Rinpoche that I didn't know when to stop feeding him, because Gesar would take everything I gave him. He never closed his mouth to refuse food, like Taggie did. So Rinpoche suggested, "Let's stage an experiment. Let's feed him and see how much he'll eat." Gesar sat in his infant chair, and Rinpoche and I fed him two bananas, a bowl of yogurt, and two pots of meat. We kept feeding him, and he ate until he threw up!

Gesar walked when he was eight months old, and he was an extremely active little boy. I remember thinking of him as a mindless body that destroyed my house. At age three and a half, Taggie began having seizures, but before that point, Taggie was actually much more in touch with the things around him than he was later, and he did talk a little bit. He was very fond of his brother and liked to take care of him. When Gesar was one and Taggie was three, they accidentally walked in on us making love. They stood at the door for a while staring at us, hand in hand. At a certain point, Taggie said, "Gesar, you can't be here. Go back to bed."

Two weeks after Gesar was born, Rinpoche and I took the two youngest boys with us to California. We stayed in the Bay Area for several weeks while Rinpoche taught a seminar on "The Nine Yanas of Tibetan Buddhism," which was the basis for a book entitled the Lion's Roar, published in 1992. Rinpoche was preparing to teach the first Vajradhatu Seminary in the fall of 1973, a three-month intensive program, during which he was going to make a formal transmission of the Vajrayana teachings to his most senior students. He saw this as a crucial step in the full transmission of Buddhism to the West, and he was thinking a great deal about the proper way to introduce this material. It was not just going to be an intellectual presentation, but he wanted to enter his students into the full practice and study of Vajrayana, which brings with it a heavy burden of responsibility for both the students and the teacher. He was acutely aware that if this were not properly done, if he failed to plant the true heart of Vajrayana in his students, it would be catastrophic for the future of his work altogether.

In preparation for the presentation at the seminary in the fall, he had decided to teach a more in-depth public seminar on the different stages of the Buddhist path. This was the "Nine Yanas" lecture series given in May 1973 in San Francisco. Rinpoche's students rented a small bungalow for us in a modest neighborhood in Berkeley, across the bay from San Francisco. I tried to attend most of the talks, but much of my time was consumed with caring for Taggie and the baby.

In early 1973, Krishna and his family had made the move to Boulder at Rinpoche's request. At that time, Rinpoche established Vajradhatu, which means "indestructible space," as the umbrella organization for all of his meditation centers and his work in the United States. He appointed a board of directors that included Marvin Casper, Fran Lewis, Krishna (also known as Ken Green), and several. others. Rinpoche wanted to overcome territorial struggles between the two power centers of his work: Tail of the Tiger in Vermont and Karma Dzong in Boulder. Not long after this, Narayana (who was now going by his given name, Thomas Rich) also moved to Boulder and joined the board. Rinpoche wanted to make Boulder the national headquarters of what he envisioned would become a large organization made up of many centers around the country. Vajradhatu and its board were set up to oversee the activities of all of the centers and the expansion of the spiritual empire, of sorts, that Rinpoche was creating. Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism was published in 1973, and sales of the book were taking off. It came onto the spiritual scene in America at just the right time to spark tremendous interest. It sold more than a hundred thousand copies in the first two years, which was a lot of books for that time. It spoke to the counterculture of that era in a direct, intimate way. More and more people came to hear Rinpoche speak. When Rinpoche gave a public talk in San Francisco during our visit in 1973, more than five hundred people attended. Within a year, there would be more like fifteen hundred in the audience.

Once again, all of these developments brought energy and chaos into our domestic life. Rinpoche had invited several members of the board to come to California with him, including Marvin, Tom, and Ken. A quorum of the board of directors was having spontaneous meetings in our dining room in Berkeley every other day and night, and the house was filled with a kind of backroom, smoky, corporate power-politics energy. The scene during this era was a bit like our version of scenes from the reality show The Apprentice. All of these guys -- and it was definitely a huge preponderance of male energy -- were learning how to be spiritual corporate types under Rinpoche's tutelage.

Starting around this time, Rinpoche began to experiment with the corporate model to see if it could be adapted as the framework for organizing the Buddhist world in America. This energy was certainly an antidote to the energy of hippiedom. Rinpoche had already put forward the idea to his students that they should view themselves as yogi householders rather than as monks and nuns. He definitely felt that a secular model was the way to go in America. Beyond that, he needed a structure for what was emerging as a large and complex spiritual organism with many arms and legs. As he brought new people onto the board, each one was given areas of responsibility. The growing staff at Karma Dzong was organized into departments, with each employee reporting to a department head who reported to a member of the board. Some of the plans for this structure were hatched in our little house in Berkeley. The group literally met around the dining room table a lot of the time. I found that I didn't want or need a seat at that table, and I watched this emerging organization with interest and some bemusement. Energy was really high during this visit.

Before going back to Boulder, we passed through Los Angeles, where Rinpoche gave a weekend seminar, and then we headed down to Acapulco for a few weeks of vacation. Gesar was only about six weeks old at this time, so it was quite adventurous of us. My sister, Tessa, was now living in Boulder, and she came along on the trip. We were invited to Mexico by Marty Franco, a student from Mexico, who paid all the expenses. She had a mariachi band meet us at the airport, and she arranged for us to stay in a diplomat's apartment, which came with maids. The maids cooked three meals a day for us. The first night they served us a cold beetroot soup, which no one liked except Rinpoche. He drank everybody's soup, and the next day his bowel movement was absolutely red and he was afraid that he had blood in his stool. I don't think he'd ever eaten beets before. The maids decided we really liked the soup, so they started making it every other night for dinner, and every time it was served, Rinpoche would drink all the soup. After a few of these meals, he finally said, "I can't drink this stuff anymore." There was a potted palm tree in the hall, planted in a hollowed-out elephant's foot, and we decided to pour the soup in the soil. Rinpoche didn't want to hurt the maids' feelings. However, they came in to clear the soup bowls just as we were pouring it out; we were never given that soup again.

There was a swimming pool in the apartment complex, and I gave Rinpoche swimming lessons while we were there. He was absolutely terrified of water. (Tibetans have no tradition of swimming at all. However, it distressed him that he couldn't swim, and he wanted to overcome his fear.) So every day we'd go into the pool together. I would hold his neck while trying to teach him to float on his back. I would tell him to relax, because he would completely tense up in the water. If I let go of his neck, suddenly he would sink. Finally, we got him a huge inner tube, so that he could enjoy being in the water and maneuver around the pool.

Our apartment had a balcony with a narrow railing that looked out over the pool. At night, Rinpoche liked to sit on the balcony and try to hit the swimming pool with melons from the fruit bowl. He usually missed, so in the morning there would be squashed melons around the sides of the pool as well as floating in the water. Eventually, the superintendent figured out who was doing this. They didn't kick us out; they just told us that we couldn't throw melons anymore.

Rinpoche also went parasailing in Acapulco.You are taken out on the ocean in a speedboat, with a parachute strapped to your body, and as the boat speeds up you're lifted into the air. I was so frightened for him that I couldn't watch. With his paralysis, I thought this was an absolutely insane thing to do. A week before a tourist had been killed parasailing. I went into the bedroom and closed all the curtains so I wouldn't catch sight of him. Apparently, when the sail brought him down in the water, he started to sink, so all these people had to swim out and save him from drowning.

While we were in Acapulco, Rinpoche wanted to take me to a tailor to have a suit made. The dress code was beginning to change in that era, and my hippie clothes no longer fit the visualization. Rinpoche thought that we should get a pale blue suit made for me, like the one that the Pan Am stewardesses wore. He thought that would be the perfect outfit for me.

Some days, we would sit and watch the cliff divers at the beach. We spent a lot of time at the beach, and Rinpoche got a dark tan. One day, when we were walking around town, an American woman came up and started talking to him in broken Spanish. He let her go on for a while, but eventually he said, "Madam, you can speak English if you want." I think she was taken aback by his proper English accent. Rinpoche also liked to go to the local market where you could bargain over the price of things. While we were in Acapulco, we took a side trip up to Tasco, where all the Mexican silver was made. It was quite a nice trip for all of us.

That summer there were further seminars at Rocky Mountain Dharma Center (RMDC). He gave another seminar on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which was attended by about four hundred students. His second seminar there that summer was entitled "The Energy of Discipline," again perhaps in preparation for the seminary. At RMDC, they had purchased a small used trailer for Rinpoche to live in. They put it on a hillside that overlooked the tent where he gave his talks. It was a tiny place with a cramped living room and kitchen combined and a small bedroom in the back, barely big enough to fit our bed. It got quite hot in there in the summer, but Rinpoche loved it. They built a deck out the front door where he could sit and look at the mountains in the distance , and he also liked to sit out back behind the trailer, under some small pine trees. He was still waking up in the middle of the night and asking for a snack, and during this era he became fond of cold Spam and tomatoes on French bread. He called this "food-o," a pun on the Japanese bodhisattva, Fudo.

That year a house was purchased for us in Vermont, about ten minutes from Tail, and we went out to stay there for two weeks at the end of the summer. Rinpoche gave it the name Bhumipali Bhavan, which means the "place of the female earth protector." Rinpoche told me that it was named for me and was to be my house, and I have always thought of it that way. It was an old Vermont farmhouse with a spacious kitchen, dining room, and large living room on the main floor and four bedrooms upstairs. There was plenty of room for the whole family there. Rinpoche taught a seminar on "The True Nature of Devotion," and a second one entitled "The Question of Reality," in which he compared the Buddhist teachings to the teachings of Don Juan, which were popularized by Carlos Castaneda in that era. Some of his students were interested in the Don Juan books, and Rinpoche indicated that there was some sanity in them, along with a lot of confused ideas.

"What is death, don Juan?"

"I don't know," he said, smiling.

"I mean, how would you describe death? I want your opinions. I think everybody has definite opinions about death."

I don't know what you're talking about.

I had the Tibetan Book of the Dead in the trunk of my car. It occurred to me to use it as a topic of conversation, since it dealt with death. I said I was going to read it to him and began to get up. He made me sit down and went out and got the book himself.

"The morning is a bad time for sorcerers," he said as an explanation for my having to stay put.

"You're too weak to leave my room. Inside here you are protected. If you were to wander off now, chances are that you would find a terrible disaster. An ally could kill you on the road or in the bush, and later on when they found your body they would say that you had either died mysteriously or had an accident."

I was in no position or mood to question his decisions, so I stayed put nearly all morning reading and explaining some parts of the book to him. He listened attentively and did not interrupt me at all. Twice I had to stop for short periods of time while he brought some water and food, but as soon as he was free again he urged me to continue reading. He seemed to be very interested.

When I finished he looked at me.

"I don't understand why those people talk about death as if death were like life," he said softly.

"Maybe that's the way they understand it. Do you think the Tibetans see?"

"Hardly. When a man learns to see, not a single thing he knows prevails. Not a single one. If the Tibetans could see they could tell right away that not a single thing is any longer the same. Once we see, nothing is known; nothing remains as we used to know it when we didn't see."

"Perhaps, don Juan, seeing is not the same for everyone."

"True. It's not the same. Still, that does not mean that the meanings of life prevail. When one learns to see, not a single thing is the same."

"Tibetans obviously think that death is like life. What do you think death is like, yourself?" I asked.

"I don't think death is like anything and I think the Tibetans must be talking about something else. At any rate, what they're talking about is not death."

"What do you think they're talking about?"

"Maybe you can tell me that. You're the one who reads."

I tried to say something else but he began to laugh.

"Perhaps the Tibetans really see," don Juan went on, "in which case they must have realized that what they see makes no sense at all and they wrote that bunch of crap because it doesn't make any difference to them; in which case what they wrote is not crap at all."

"I really don't care about what the Tibetans have to say," I said, "but I certainly care about what you have to say. I would like to hear what you think about death."

He stared at me for an instant and then giggled. He opened his eyes and raised his eyebrows in a comical gesture of surprise.

"Death is a whorl," he said. "Death is the face of the ally; death is a shiny cloud over the horizon; death is the whisper of Mescalito in your ears; death is the toothless mouth of the guardian; death is Genaro sitting on his head; death is me talking; death is you and your writing pad; death is nothing. Nothing! It is here yet it isn't here at all."

Don Juan laughed with great delight. His laughter was like a song, it had a sort of dancing rhythm.

"I make no sense, huh?" don Juan said. "I cannot tell you what death is like."

-- A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with Don Juan, by Carlos Castaneda

Ram Dass attended this seminar, having connected with Rinpoche in Boulder earlier that year. Rinpoche teased him a lot during the talks. At one point during a talk, he had Ram Dass sit at his feet, and he dropped the ashes from his cigarette onto his head. Ram Dass was quite into the outer purity approach: wearing white, eating special food, and doing purifications of the body. So perhaps Rinpoche was making a statement to him about innate purity.

In one of the most vivid dreams, I lived in a nunnery on a large white lake in Tibet… in a large room dominated by a huge white statue of a Buddha… people from a nearby village raised the money to build a white facade to the cave…. Rinpoche was going to marry a white girl…. We undertook other commando operations with odd code names: Operation Awake, Operation Blue Pancake, Operation Secret Mind, and Operation Snow White…. The women who [served] in the rest of the house wore white aprons with very ostentatious white shoulders over a black dress….. In Boulder a large white mansion on Mapleton Hill, about six blocks from our house, was rented for [H.H. Karmapa].…. I had a white Mercedes at the time, which I loaned to the dharmadhatu for His Holiness's use during the visit…. Rinpoche and I were both dressed in white….[Rinpoche] insisted that we should only have white towels in the bathroom. His philosophy was that with white towels you could see if they were dirty. Rinpoche himself didn't like to shower, but he insisted that we had to have these pristine white towels….. We started out wearing simple white clothing, somewhat like being on stage in our pajamas. This signified our basic human nakedness, which was adorned progressively throughout the course of the enthronement….. Rinpoche was given a white naval peaked cap, and His Holiness blessed a small white gold tiara inlaid with diamonds for me (a gift from Rinpoche)…. I noticed how beautiful the purkhang was, ornamented with its gold designs and with the Mukpo colors: brilliant white, bright red and orange, and deep blue….. A white cloud in the shape of an Ashe appeared.

-- Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chogyam Trungpa, by Diana J. Mukpo with Carolyn Rose Gimian

In any case, their interactions were quite playful and fun to observe. Ram Dass was taken with Rinpoche in that era, and they were making plans to teach together. His long-haired Hindu persona was a contrast to the approach now developing within the community. We were starting to wear more conservative dress at that time, not yet suits and ties, but the bare-chested men were putting on shirts, and the madras and paisley were disappearing.

Then in the summer of 1974 I was at Naropa Institute teaching a course in the Bhagavad Gita, a course for which I felt Maharaj-ji was giving his blessings. There at Naropa I was part of a whole other scene, because Trungpa Rinpoche represents a different lineage. I found myself floundering a little bit because my own tradition was so amorphous compared to the tightness of the Tibetan tradition. Trungpa and I did a few television shows together. We did one about lineages and I felt bankrupt. I had Maharaj-ji's transmission of love and service but I knew nothing about his history. I didn't know how to talk about what came through me in terms of a formal lineage. I was also getting caught in more worldly play, and I felt more and more depressed and hypocritical. So by the end of the summer I decided to return to India. I didn't know what I'd find, but I'd go anyway. I knew I was different than I was ten years before, but I was still not cooked, and what we owe each other is to get cooked.

-- Grist for the Mill, by Ram Dass

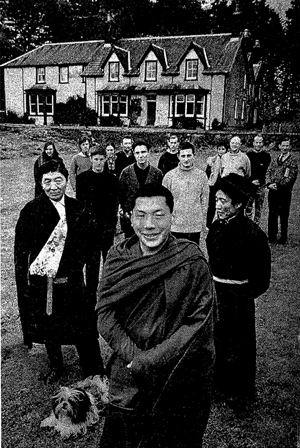

At the end of September, Rinpoche went off to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where the first seminary was being held at the Snow Lion Inn. There were less than one hundred students accepted for the seminary, because Rinpoche wanted to be sure that he had a small group to whom he could impart these teachings very intimately the first time. There were many qualified people, but he took less than half of those who applied. It was important to him to have the right group and the right chemistry among the students and with him. Everybody lived in the lodge, and there was a schedule for everybody to help with cooking, cleaning, and other chores. The program was divided into three sections: Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. Each section was further subdivided into a practice period and a period of study, during which the students attended discussion groups and took courses from student-instructors during the day and attended Rinpoche's talks in the late afternoon or evening.

The seminary began with a week of sitting meditation. Everyone was expected to sit from seven A.M. until eight or nine o'clock at night, with breaks for meals and chores. Rinpoche gave one orientation talk, and then left for the week while people meditated. He went right back out on the road and gave talks in Boston while people were practicing at the seminary. He wanted them to really clear the decks, so to speak, by sitting for a week before study commenced.

When the seminary started, I was left back in Boulder with Osel, Taggie, and Gesar. Felicity had gone to live with her grandmother by this time. I was going for the Vajrayana portion of the program at the end of November, but I just couldn't take the children there for the whole three months. I celebrated my twentieth birthday on October 8, and I felt so lonely. This was the first time Rinpoche had been away for my birthday since we were married. He had celebrated my birthday each year with a special dinner, a gift, or a small party, which was really important to me, especially after the way my mother often ignored these events during my childhood. Some friends organized a small party, but I was still missing him. I went to my birthday party telling myself that I would have a good time. After everyone arrived, the host said that Rinpoche had sent a present for me and that it was in the closet. With much urging, I opened the closet door, and out he came. He had come back for my birthday.

He stayed a night or two and then went back to the seminary. I joined him there with the two youngest boys about a month later, just before he began presenting the Vajrayana teachings. This was such a significant event for Rinpoche. There were many reasons why he might not have gone ahead with this. For one thing, although there was a great deal of interest in Eastern religion at this time, there was also tremendous naivete and spiritual materialism in the United States. Many people saw Tibetan Buddhism as a set of magical and esoteric teachings and as a way to gain instant -- or at least quick -- enlightenment. There was much misunderstanding about what genuine spirituality is in the Buddhist tradition. Teachers like Suzuki Roshi had laid the ground for a true understanding of Mahayana Buddhism and had begun to teach the importance of practicing the teachings through meditation and applying them through the discipline of everyday life. However, there were still huge areas of misunderstanding.

Rinpoche had been working extremely hard to plow what he saw as fertile but confused ground, planting the genuine seeds of dharma in the American soil. During the three years that he had been in the country -- and it had only been three years -- his students had transformed themselves in many ways. He always attracted an incredibly intelligent bunch, and he nurtured that intelligence and encouraged a degree of cynicism and doubt to cut through the fascination with spirituality as a gadget or a toy. However, he also had to work with the ingrained individualism of the culture, which was both a strength and an obstacle to understanding the nature of a real devotional relationship between teacher and student. There has to be a degree of giving in or surrendering one's hard edge of egotism; otherwise, the Vajrayana teachings in particular can be perverted into egomania or misconstrued as purely an intellectual, or mind, game.

When people see photographs or videos from the very early days, what they are shocked· by is how disheveled, underdressed, and hairy everybody was. In fact, that was a relatively small obstacle. The real question was whether Rinpoche could actually penetrate past the shell, the veneer, that people were presenting. Could he get to the heart of the matter with them? It was still an open question for him after all this time.

He gave twenty talks in the first part of the seminary, in which he presented the Hinayana and the Mahayana aspects of the Buddhist path. People weren't sitting as much as he would have liked; they were partying a bit too much, but generally he was pleased with people's attitude and openness. He felt that people were ready and receptive for him to launch into the presentation of Vajrayana. This was a detailed but also very deep presentation of the path of tantra. He was pouring information into people, but much more than that, he was pouring his heart and the heart of his tradition into the minds and hearts of the students. Once he started, he was so inspired that his talks grew longer and longer. He himself was studying the teachings of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great, his root teacher's predecessor, as the basis for his presentation, and he was so animated and excited to be able to share this material with people.

About halfway through the Vajrayana section of the seminary, just as he was reaching a crescendo in the presentation of the material, as he began to describe the parts of the path that were central to the practices that his students would soon begin to practice -- just at that point, there was a disastrous incident. One afternoon, Rinpoche was so inspired that he talked for several hours without giving us any kind of a break. He seemed ready to continue lecturing on into the night. People began to get restless and fidgety. Usually the talks took place before dinner, and people were getting hungry. Their appetite for Rinpoche and the teachings, which had seemed insatiable for so long, was now overridden by their appetite for dinner. People were, I think, a bit overwhelmed by what Rinpoche was presenting, so their restlessness in part reflected their inability to take it all in. He went beyond anyone's idea of what was acceptable, conventional, in terms of how long he talked. Finally, someone suggested taking a break and continuing the next day. Then one of Rinpoche's closest students, who was a member of the board and someone we were very close to, suggested to Rinpoche that they vote on whether to continue or to stop for the night.

He could not have made a worse suggestion. The idea that the timing of the inaugural presentation in America of the essence of Rinpoche's lineage was going to be decided by a vote, by democratic process, was antithetical to the understanding of devotion that Rinpoche had been trying to foster in his students. It suggested to him that perhaps they hadn't heard a word he had said. When the students applied and were accepted to the seminary, it was like becoming engaged, in a spiritual sense. It wasn't a casual invitation. Presenting the Vajrayana teachings was, for Rinpoche, like getting married to these students. They were mutually about to embark on a relationship that would last throughout the rest of their lives and hopefully one that would be transformative for everyone involved. Essentially, he and the students were at the altar, in the middle of a wedding ceremony. When they decided to take a vote, he was about to present the ring, kiss the bride, and say, "I do." They were asking him to stop the ceremony in midstream.

He asked them to repeat what had been said. Someone else said, "Let's vote." He threw down the microphone and walked out of the hall. As he strode out, someone said, "Rinpoche, come back. He doesn't speak for all of us." It was too late. The air was black. He was never coming back. People sensed that immediately.

Rinpoche had been waiting ever since he came to the West to make this presentation. America had been waiting centuries for these teachings. But the students couldn't wait to have their dinner. It was over.

It seemed that way for several days. I have never seen him angrier. People were devastated. A huge black space hung over the seminary. Slowly, there was an outpouring of people's love and dedication to what was happening there. The students supplicated Rinpoche to continue. In the end, he saw, I guess, that there was ground to go forward, without compromise. Four days later he started to teach again, and this time, people were ready to hear what he was presenting, with no strings attached, no boundaries. He went forward and completed the presentation, and it was beyond magnificent. These were really unspeakably brilliant teachings.

What was so interesting was that when he got over his anger, he was completely over it. There was no hangover. Of course, people never forgot that lesson, and news of what had happened spread throughout the sangha. In a way, it completely changed the tenor of the space in which he taught from then· on. It wasn't a game. It wasn't a party. This was real.

During the last days of the seminary, we received the sad news that Alan Watts had died suddenly of a heart attack in California. The next day Rinpoche and I were alone, sitting together in our room. We both turned to each other at the same time and said, "Alan Watts." We felt him go through the room at the same instant. I'm sure his consciousness passed through.

At the end of the seminary, just a day or so before we were preparing to return to Boulder, Rinpoche said to me, "You know, I might die soon." I said to him, "What do you mean?" He responded, "Well, now that I've finished the seminary, I've taught everything I have to teach. There's nothing left for me to present. So I might die soon." He'd been in the United States for just three years. Now, he was saying that he'd done all he could. I told him, "That can't possibly be true. There must be something more." He paused for a minute, and then he said, "Yes, well, I have been having dreams about being a general. I had one last night. I was a general and I was leading the troops in battle. That was fantastic." Then he said, "I'd love to be a general." Finally, he said, "I guess if I could become a king and rule a nation, then I would have something to live for!"

This was one of those times when I realized that I did not know at all what to expect from Rinpoche. Ultimately, I don't think anybody did. You could never apply the same logic to Rinpoche that you could to other human beings. When you're very close to somebody, you presume that when a situation comes up, you can predict how this person is going to react. With Rinpoche, you never really knew, because he was operating in such a vast space compared to ordinary people. I wondered what to expect from him in the future. Clearly, it would be something out of the ordinary.