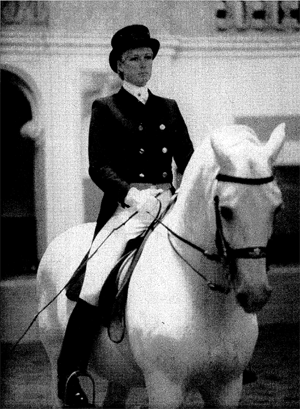

THIRTEENIn the months before Rinpoche left for retreat, I was making my own plans for the coming year. I began to turn my mind to going to Europe to further my dressage training. Since Rinpoche and I had been deeply impressed with the Spanish Riding School when we visited Vienna in 1975, it was natural to think about studying with someone from the Spanish as the next step in my education. At that time, I did not think it would actually be possible for me to study in the school itself; it was an all-male institution, and, as far as I knew, they only accepted Austrian nationals as riders in the school.

When we watched the performance there, one rider in particular had impressed me, Ernst Bachinger. I wrote a letter to him in early 1977 telling him that I would like to come and study with him. He replied that he had just left the school and was in a time of personal transition, so he was not accepting new students. He recommended that I train with Arthur Kottas, who had his own training facility near Vienna. I wrote to Kottas and asked him if he would accept me as a student.

Within a month, he wrote back saying that I could come that summer. Rinpoche was tremendously supportive of my going to Vienna, much more so than he had been about California. He felt that the classical tradition practiced in Austria was the real McCoy, so to speak. When I received the letter of acceptance from Kottas, we were both overjoyed.

Mter Rinpoche left for Charlemont, I stayed on in Boulder for several months, preparing for my trip. I took German lessons from the Berlitz Institute in Denver so I would be able to communicate a little bit in German with my teachers and fellow riders. I also sold Vajra Dance before leaving. I knew that I would need a better horse in Vienna.

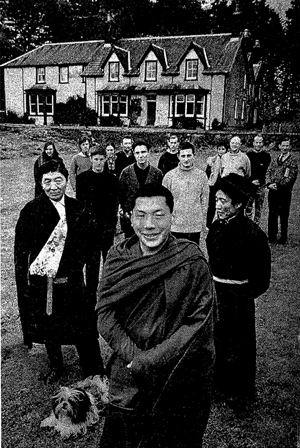

Rinpoche had been thinking for some time about establishing Vajradhatu in Europe. There was already a meditation group in England, but he felt it was time to start something on the continent. He also wanted me to have support, being a bit worried about me going over to Vienna alone. He asked one of his close students, Michael Kohn, if he and his family would move to Vienna to start the Vienna dharmadhatu, to get things rolling in Europe. Michael was to be the Vajradhatu ambassador to Europe. Michael was a very literate person who had worked on a number of Rinpoche's early books and other editorial projects, and he had a facility with foreign languages. He was very devoted to Rinpoche and had been trained by him as a meditation instructor and teacher, and for all these reasons Rinpoche thought he would be an excellent person for the job. The plan was that Michael would be based in Vienna and would travel and teach in a number of locations throughout western Europe. Michael, his wife Judy, and their daughter (a second child was born in Europe ) relocated to Vienna around the same time that I did. The Vienna dharmadhatu has continued to this day, although after I left, Michael and his family relocated to Amsterdam and then finally established the headquarters of Vajradhatu Europe in Marburg, Germany.

Rinpoche also wanted me to have someone to help out at the house, and this was the beginning, really, of my having personal attendants. Rinpoche asked Jeanine Wieder, a French woman in the sangha, if she would accompany me. During this era, Rinpoche was trying to include the family and me much more as part of the environment of the teachings that should be respected. I think that he may have realized that there was a problem with the large discrepancy in how students treated him -- almost like a god -- and how we were treated -- often like unwelcome interlopers in his life. With the emphasis on a Court mandala in his presentation of the Shambhala teachings, it made sense that the entire household had to be included and regarded as part of the sacredness of his world. As well, the message he Was trying to communicate to all of his students was that every part of one's life is part of one's practice. You don't just meditate in the midst of your dirty pots and pans, ignoring your spouse and children. Given the hippie roots of many of his students, there was sometimes this tendency to ignore the basic details and fabric of everyday life. In fact, this was one reason that some of Rinpoche's students were resistant to his presentation of the Shambhala teachings. They didn't want to have to clean up their act. They liked the smelly nest, which Rinpoche referred to in his Shambhala presentations as "the cocoon."

My mother wrote an amusing letter to Rinpoche during the first month of his retreat, March 1977, about her view of hippie society in Boulder and why Rinpoche would want to get away from it for awhile. She wrote, "I can understand that you might want to escape the trivia that populate Boulder with its various cares and stores. Most of these people appear to lack all idea of personal grooming and one cannot begin to imagine whether anything exists within the cerebral cranium. It is a horrifying aspect of an ignorance bordering on barbarity."1 Rinpoche I think shared her view that people looked worse than unkempt on the outside, but he saw the intelligence behind the "barbarous" exterior.

At this time, Rinpoche was beginning to work much more with promoting feminine energy, not just in the abstract -- which is certainly an important part of the Vajrayana Buddhist teachings -- but the energy of women in the community. I think it's interesting that this coincided with his presentation of the Vajrayogini abhisheka. Vajrayogini is the personification of wisdom and represents the feminine principle. But interestingly, at the same time that he started giving this practice to people, he also began to appoint many more women to important leadership roles, and he suggested that I should also have such a role within the Shambhala world. Rinpoche's contact with and understanding of Western women had been growing exponentially since he came to North America and since we married. I think he got to know "woman" on an intimate, day-to-day basis in part through our marriage, as well as through other relationships with Western women students. Just as he broke through so many other cultural divides, his chauvinism began to wear out in a fundamental way, and he started to feel that women could play very important roles. Here again, we take these things for granted now, but in that era, leadership was not as open for women as it is now.

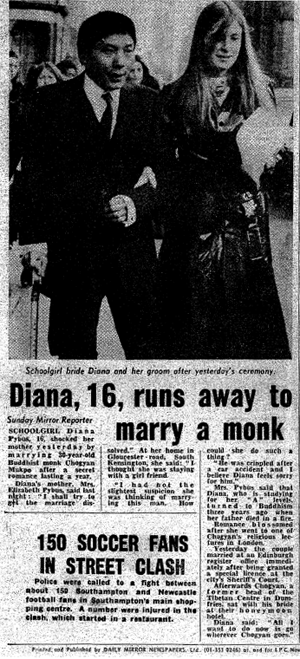

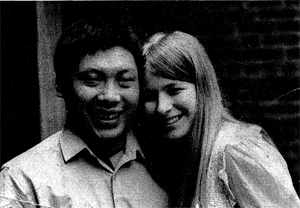

In any case, during this period, one of the changes that he instituted involved elevating my status, which was often uncomfortable for me. I don't think I always handled it well, especially in the beginning. At the seminary the previous fall, Rinpoche had floated his idea with some senior students that perhaps I should now be addressed as Her Highness Lady Diana Mukpo. He said that he wanted me to have a tide that was commensurate with him being referred to as the Vajracharya or the Sakyong. David Rome, among others, tried to talk him out of this, as did I initially, but he would not be dissuaded, no matter how ridiculous people told him it was. I reluctantly came to the conclusion that, if we were going to live in a Shambhala Court, it would not be completely inappropriate for me to be a lady. Within a few months, I became used to people calling me "Your Highness" within the Buddhist community. I still found it awkward when this tide was used in the larger world by well-intentioned but -- from my point of view -- naive community members.

I think that one reason that students were willing to "attend" me was because of all this energy that Rinpoche was putting into expanding the Shambhala world and extending that into our home. Jeanine referred to me at home as "Lady Diana." Unfortunately, she also called me that frequently when I was riding at Kottas's barn, no matter how many times I asked her to just call me Diana when we were there. On some level, I didn't find it that bizarre, but I was trying to keep these two worlds separate. When Jeanine called me Lady. Diana at the barn, I cringed. I wanted to be ordinary in that situation, get my work done, and focus purely on my riding.

For my first day at Kottas's school, I drove through the Vienna Woods and turned off onto a small driveway that led to his barn. The barn was in a large clearing, and there were about twenty-five horses stabled there. There was a well-appointed indoor arena, as well as paths on the property where you could ride your horse through the forest.

I was dressed in my best riding clothes, and I was quite excited. I thought I was pretty hot stuff, and I imagined that I would impress Herr Kottas. He greeted me and told me that he had a nice horse for me to ride. He said, "Let me see what you can do." The horse was the current Austrian champion. I realized almost immediately that I was in trouble. I couldn't make the horse do anything. Obviously, the way I had been trained to ride in the. United States was completely different from what they expected in Vienna. I felt humiliated. Afterward, I went out for coffee with Kottas, and he said to me, "If you don't improve greatly within the next three months, you'll have to leave. I'm represented by my students. If you don't get better, you'll go. That's that."

He told me that if! wanted to stay and train with him, first I would have to go to his barn every morning while he was away riding at the Spanish. I would report to his assistant, and she would longe me. Longeing is a means to teach the rider to sit correctly on the horse. The instructor has the horse on a long line called a longe line. You sit on the horse without reins or stirrups,. and you learn how to balance and keep your body in exactly the correct position. Kottas wanted me to return to this absolutely basic training before going any further.

I agreed to his terms, and starting the next day, I reported every morning to his assistant, a German woman named Jutta. Every morning, I was given the same horse to be longed on, a seventeen-hand Bavarian warmblood by the name of Donald. Donald had a terrible habit of bucking, and he bucked me off almost every day. It was a good day if I hadn't fallen off him. I spent my first three months sitting on this horse and ending up in the dirt on an ongoing basis. Fortunately, I was never seriously hurt, hut it wasn't a pleasant experience. When I fell off, Jutta would say to me, "Get up. Get back on." She never said, "Are you okay?" The custom at the barn was that you were expected to buy a liter of wine for people every time you fell off a horse. At one point, I bought eighteen liters of wine. I invited everyone; I put the wine out for them and said "Drink up!" It was a miserable time.

After about a month of this, I became discouraged and convinced that I was never going to make any progress. I felt ready to pack up and go back to the United States. I missed everyone terribly, especially Gesar, and I thought that at the end of the year I would go home. I called Rinpoche a number of times to discuss all this. I was looking for understanding and sympathy somewhere in my life. Altogether, I felt discouraged and inadequate.

In mid-September Rinpoche wrote me a letter. To me, it exemplifies how he worked with all of his students. He was immensely kind and loving, but he expected a lot from everyone -- especially his wife, as I realized when I read what he had written. It was somewhat shocking, because he was so honest and unguarded and offered such direct advice. He wrote:

My darling,

Isn't it magnificent that I am writing a letter to you? We have never communicated with each other in this way before. Usually we use a telephone or mutual mind contact. But I hope that what I have to say in this letter won't shock you too much.

I have never met a human being like you. You are so extraordinary, outrageous, and intrinsically good. I miss you a lot, but sometimes I feel for your future. I want you to be the world's most outstanding dressage rider. This is not just because I am going along with your schemes or your plans, but I want you really to become a truly good equestrian. Therefore I would like to push you in your discipline.

Thank you, by the way, for your letter and your phone calls. I understand how you feel about all of this, the riding and your disappointment in the Spanish Court Riding School. But I would like to encourage you as your husband and your good friend. I do not want you to chicken out. I want you to know that my pride is not purely invested in you as my famous wife. But I certainly do feel that it is my role and my delightful duty to push you to become the top rider in the dressage world. Therefore I would like you to stay longer with Kottas and study with him. Any financial or moral support, whatever is needed, I obviously volunteer. Of course, it is my duty.

Sometimes you feel disappointed because of your impatience. Sometimes you feel disappointed because of what you expected' from the best system of dressage in the world. If you could stay beyond Christmas and at least spend next year with Kottas, I would feel more proud of you. You might find it strange that my urge to push you becomes greater. As far as I am concerned, it is my pride in you and in me. I hope you will never give up all this. Please consider: patience is great .... I want you to stay with the discipline of the Spanish Court Riding School. If this seems unreasonable, let us talk about it when we are together -- but I want you to stay in this school.

You said the European championship was so materialistic. Sometimes it is necessary to give in to people's trips; otherwise there is no working basis. As long as you are not hypocritical to yourself, that is the key to remaining genuine.

There is something to the Spanish Court Riding School. It is internationally acceptable, and moreover it has a great lineage which has been handed down from generation to generation. You can't find that kind of inspiration from individual practice alone. I know that; I have done it myself. If you try to do your own trip and practice riding by yourself independent of any tradition, you are going to become the Ram Dass of the dressage tradition.

You might want to do it on your own terms, but self-styled disciplines are dubious. Only the Americans do things that way because they don't like the discipline of the forefathers of whatever lineage they might have belonged to. Instead, they prefer to give up any pain they feel and try to insert their own pleasure by manufacturing their own discipline. Darling, I don't want you to become Americanized. It is silly and ridiculous.

Sweetheart, I don't want to push you, but I feel if you trust me, my judgment is right. I know it is painful and uncomfortable not being with our people, but our people will appreciate you more if you come back victorious and good. I really insist on this, you know. Please think it over. We can discuss it when we are together.

The main point is that you realize that no discipline will come along with hospitality. Exertion and diligence beyond physical discomfort are the key.

Your most loving Sakyong and husband writes this letter remembering you with tremendous love and longing. Sweetheart, I remain your most obedient husband, the Sakyong ....

I love you CT2

I couldn't ignore a message like this. It was really the heart advice that I would have given myself, had I been able to transcend my own doubt and see things from a bigger perspective. Rinpoche told me things that at some level I already knew and believed. I had to admit that he was right. From that point on, my attitude changed. I gave up any thought of leaving, and I started to work really hard. Between that and my change of attitude, I made quite a lot of progress.

In his letter, when Rinpoche told me that he didn't want me to become "Americanized" in my approach to riding, he was appealing to my English chauvinism. From the time we arrived in the United States, although we both appreciated the fresh, unbridled quality of the American spirit, we were also both aware of what we perceived as a lack of discipline and a rejection of tradition. As much as I rebelled against my upbringing, there was much that I appreciated about the British mentality. It was part of me. There was a stuffiness and close-mindedness that I reacted against, but I also learned about genuine discipline from growing up in England. I also appreciated that Rinpoche had this connection to discipline from his own education and upbringing, so I knew that he spoke from firsthand experience.

In terms of my education as a rider, before coming over to Europe, I had realized that there was something missing in my training in America. I had seemed to make extremely rapid progress there, but the foundation of the discipline was not well established, and a certain attention to the basics was missing. Having to start over from the ground up was not just helpful but essential to my progress as a rider.

In dressage, the first objective for the rider should be to learn to follow the horse's movements and to be able to stay in balance with the horse, without hanging onto the reins or squeezing with your legs. First, you have to learn to harmonize with the horse's movement, and this process can take a long time. If riders don't have correct training on the seat position early on, it's going to show up later in their riding because there will be always be some degree of inability to harmonize with the horse. And if the rider can't harmonize with the horse, then the horse's movements can't be graceful or beautiful.

When dressage is performed at the highest levels, with a skilled rider and a well-trained horse, the communication between the horse and the rider should be almost indiscernible. This certainly doesn't mean that the rider is not doing anything. The rider may be doing quite a bit, giving the horse various aids or instructions. This is done through leg movements, how you hold the reins, and how you sit in the saddle, but all of this should be so extremely well-timed and subtle that the casual observer may notice nothing but the unity of horse and rider. It takes a minimum of five years to train a dressage horse to the highest level. Throughout that process you refine the aids. When you see a completely finished horse, when you watch him going through all the highest movements of dressage, the rider's influence should be almost imperceptible. Horse and rider should look as if they're moving as one.

It was this basic connection to the horse that I was gaining through my work on the longe line. Rinpoche was absolutely correct about the training in Europe. Especially in Vienna, where they follow this classical approach, training is not based on immediate gratification. New riders always spend a long time on the longe line. When you longe a horse, it is controlled by the instructor on the ground, and the horse walks, trots, and canters on command, in a circle around the instructor. The student's only objective is to learn how to sit, and how to synchronize and to follow along with the horse's movements. I was told that in the Spanish Riding School, the young apprentices would often longe for six months before they're ever given the stirrups or the reins. In the end, I was grateful to have had a similar experience.

Several weeks after he sent me the letter, Rinpoche came over to Vienna. I guess you could say that he took a kind of vacation from his retreat! He traveled with a group of his students to see me and to check in on how Michael Kohn was doing setting up the European branch of Vajradhatu. I was delighted to see him.

Kottas's training facility was near a small village called Tulbingerkogel. There was a very nice hotel in the village, the Berghotel Tulbingerkogel, a few minutes up the road, owned by the Blauel family. Rinpoche and his party stayed there. (Interestingly enough, one of the sons in the Blauel family later became a member of the Buddhist community.) John Perks accompanied Rinpoche, as did Sam Bercholz. The party also included Jim Gimian, who Rinpoche was about to appoint to an important post within the vajra guards. Jim's rank was to be just below David Rome. Rinpoche had decided to create two divisions within the guards. Jim was to be the dapon, or chief, of the kasung division providing the outer protection for Rinpoche and his world, while John Perks was being appointed as the dapon of the kusung division, which included the personal attendants, or the inner service, to Rinpoche, myself, the Regent, and a few others. Jim, a very warm man with a great sense of humor, was also the associate publisher at Shambhala Publications.

Rinpoche had also invited Sara Kapp to accompany him, a runway model well known in both New York and Europe. Sara was famous for having pioneered a certain look on the runway, and she became the model for mannequins at Saks Fifth Avenue in the eighties. Later, she was the first "Princess Borghese," the face of the Borghese line of cosmetics.

In short, she was a very elegant woman, and she was one of Rinpoche's close friends, girlfriends, at the time. Several famous Italian and French designers had loaned Sara evening gowns to wear on this tour of Europe. Every evening, she would appear for dinner in yet another extraordinary outfit. I was by this time in our married life quite accustomed to Rinpoche having relationships with other women. In general, for whatever reasons, I did not find them threatening or degrading. Many of these women were my friends. We shared the appreciation of Rinpoche as an extraordinary human being, someone who no one person could possess in the traditional sense. I did find it difficult if a woman spending time with Rinpoche did not have some respect for my position as his wife. This was rare, luckily. In Sara's case, we were old friends, and I was happy to see her.

Rinpoche, as I mentioned earlier, had always made an effort to celebrate my birthday with me, and this year was no exception. I turned twenty-four while he was in Vienna. Throughout the visit, John Perks shaved his moustache to look "Hitlerian," and Rinpoche kept saying "Fetus" to people instead of ''AufWiedersehen,'' which means good-bye in German. No one seemed to notice. I'm sure they just thought he couldn't speak the language. Rinpoche and John were often making fun of Austria's Nazi past in the most tasteless fashion. (Rinpoche could make fun of almost anything.)

For my birthday, Rinpoche reserved a private room at the hotel and ordered a whole wild boar to be roasted and served at the table. It cheered me up a lot to have him and his crazy, loving world there for a few days. During his visit, we ate a lot of Sacher torte for dessert, which Rinpoche was very fond of.

While he was there, Rinpoche and I talked further about my riding. I told him that I was going to stick it out and also that I had heard that the Spanish Riding School was now accepting a few foreign students. It was my extraordinary good fortune to be there during this era. I told Rinpoche that it was my greatest desire to work hard and progress so that I would be able to apply. I understood at this point that it was only by following the approach he was suggesting that I would ever master the discipline to the point that I might be accepted.

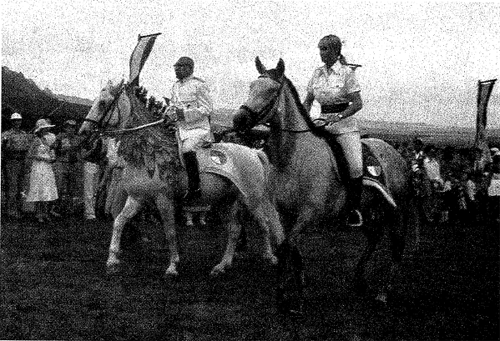

Rinpoche came out to Kottas's barn to meet him and to see me ride, and he really loved it there. He had ridden in Tibet, and from that he had a great appreciation for riding, as well as an intuitive feeling for it. I also took him and his party to the Spanish Riding School. Since I was now studying under one of the riders at the school, I was able to arrange for Rinpoche and his party to watch the morning lessons and to have a private tour of the facilities, rather than having to attend a performance with a huge crowd of people. I was so sad to see him leave, but altogether, his visit gave me the further encouragement I needed.

For the next year, I continued my training with Arthur Kottas. At the end of Rinpoche's retreat, December 1977, I traveled back to Boulder to spend time with him. Throughout 1978, I made several visits to the United States to participate in various activities in the Buddhist community, but for most of this time I was based in Vienna.

A few months after I settled in Vienna, Taggie came through on his way to His Holiness's monastery in Rumtek, Sikkim, chaperoned by Karl Springer. When His Holiness had made his second visit to America, he saw Taggie at Karme Choling. He strongly suggested to Rinpoche and me that we allow Taggie to go to Rumtek, where he would be formally enthroned as Tenga Rinpoche. His Holiness thought this might help Taggie. I had visited my son at Karme Choling several times, and during that period I continued to hold out hope that he was going to somehow become a more normal child. When I saw him in Vienna, however, it was absolutely clear that he was not normal, and I began to give up any expectation. At this point, although he was my child and always will be, I became more disconnected from him. I didn't know what else to do. His life was out of my control now. Rinpoche had agreed with His Holiness and made the decision to send Taggie to Rumtek. I couldn't care for him. When he came through, it was very difficult for me because I felt our connection dissolving. I felt the hopelessness of it all. I remained skeptical that Taggie's condition was tulku disease.

Perhaps in part in reaction to the pain of seeing Taggie, I threw myself even more into my riding after his visit. At a certain point, when I began to feel that I was making adequate progress, and taking to heart Rinpoche's offer of financial support, I decided to purchase a horse for myself.

I wanted a horse that was already trained to the medium level in Europe. (This is roughly the equivalent of the fourth, or highest, national level in the United States. After that there are four international levels, which are the same throughout the world.) Kottas was kind enough to accompany me to Munich to look at a Hungarian horse that was owned by a woman by the name of Katrina Hilger Henkel (of the Henkel family who produces a popular sparkling wine in Germany). Her stable was near Munich, where she had competed him through the medium level of dressage. When I rode the horse, I instantly felt a connection and felt he suited me well. He was a chestnut horse, maybe sixteen one hands, not very big, but very pleasant to ride.

There are certain guidelines one uses in picking a horse for dressage. When you evaluate a young untrained horse as a dressage prospect, you are looking for a very sensitive horse. When he's young, he might misbehave sometimes, but you want that sort of hot temperament, because that shows you that he's sensitive and energetic. If a dressage horse were a person, he would not be a couch potato. Dressage becomes very taxing physiologically as the training goes on, so you need a horse that is a natural athlete. That's one thing to look for: the athletic ability of the horses, as well as their desire to do the work. You want a horse with plenty of energy when it's young.

Male horses are generally better for dressage. There are very few mares in competition, although there are some very good ones at the top of our sport. At the Spanish Riding School, only stallions are used. However, the vast majority of dressage horses in competition are geldings, castrated males. The problem with the stallions is that they often have other things on their mind than dressage and therefore need a very experienced rider.

When I was at the Henkel barn, I saw another horse that absolutely wowed me. He was my ideal of a dressage horse at the time, a sixteen two hand liver chestnut Hanoverian who exhibited tremendous energy and supple movements. I asked Katrina Hilger Henkel if that horse was for sale, but she was not willing to sell him. We ended up buying the Hungarian. I brought him back to Vienna and named him Shambhala. Two weeks later, I got a phone call from Katrina, telling me that the other horse was now available. Without much hesitation, I agreed to buy him as well, much to the understandable consternation of the financial people in Vajradhatu to whom Rinpoche turned to finance the purchase. In Vienna, I was surrounded by wealthy people, many of whom had a number of expensive horses, and I think I lost my perspective a bit.

There was one person within Vajradhatu in charge of our family finances, Chuck Lief, a student of Rinpoche's since 1970. Chuck was quite upset, and I don't really blame him; I had just gone ahead without thinking, saying, "Fine, we'll have the second horse as well" -- and they certainly were not inexpensive. Over the years, Chuck had a lot of handwringing to do in connection with my dressage horses.

Nevertheless, both purchases went ahead, and within a few weeks, I ended up with two very interesting horses to ride and compete. I named the second horse Warrior. In 1978, I began competing Shambhala in Austria. The first year, I didn't do dismally, but I was not tremendously successful. However, by the second year, I did very well with Shambhala, winning a number of tests at the medium level. Toward the end of my time in Vienna, I started competing both horses in the first international level, the Prix St. Georges.

Studying with Arthur Kottas, I was learning how to be a good rider. Kottas's approach was very demanding; it was very tough training for me, but it was necessary to go through this process. I was also beginning to learn how to train my horses. I began to realize that, as a rider, you are like the personal trainer of the horse. It's very much a mutual relationship; the rider also has to learn to listen to the horse. If you're a really good rider, you're going to discover how your horse wants to be ridden. You have to learn to adjust to the needs of each horse. Every horse is different, and the hallmark of a good rider is that he can get on many different horses and quickly figure out where the problems are. To begin with, the horse always has to be obedient to the rider and has to follow the direction of the rider. On the other hand, the rider has to be able to communicate to the horse in a precise manner what he wants the horse to do. So dressage involves two-way communication.

If you look at dressage training in terms of the alphabet, when you ride a very young horse, you only teach him the letters A and B. A is that he must go forward, and B is that he has to stop. Ultimately, when your horse is at the Grand Prix level, he should know all twenty-six letters, so to speak, and you should be able to make words with them. How does the communication take place? It has to be accomplished through subtle movements, by closing your leg, by bracing your back, by putting pressure on your seat bones or closing your fist on the reins. As a result of training, all those little things mean something to the horse, and eventually the different combinations of those aids will also mean something to him.

Dressage is a bit like ballet. In the early training, you concentrate on basic movements. The basic elements eventually are put together into complex movements that look somewhat like dance. On the other hand , it's quite different than becoming a dancer in that you are trying to train not just your own mind and body, but also the mind and body of another being, a huge, twelve-hundred-pound animal. You are trying to harness and direct the energy of this being, and beyond that, you are trying to connect with the animal in the most fundamental way, so that at times, there is no division between you and the horse. You feel that you are completely in sync, physically, mentally, and one might almost say spiritually, or at least energetically.

In the Shambhala teachings that Rinpoche began presenting in this era, there is extensive discussion of the principle of windhorse, or lungta in Tibetan. This term refers to raising or harnessing your energy. Rinpoche described lungta as follows:

When we pay attention to every thing around us, the overall effect is upliftedness. The Shambhalian term for that is windhorse. The wind principle is very airy and powerful. Horse means that the energy is ridable. That particular airy and sophisticated energy, so clean and full of decency, can be ridden. You don't just have a bird flying by itself in the sky, but you have something to ride on. Such energy is fresh and exuberant but, at the same time, ridable. Therefore, it is known as windhorse.3

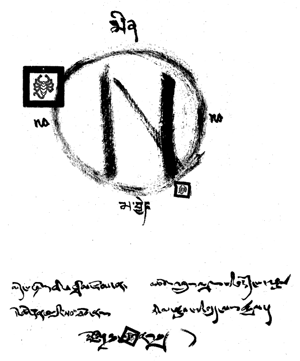

Lamas sending Paper-horses to Travellers.

Lamas sending Paper-horses to Travellers.***

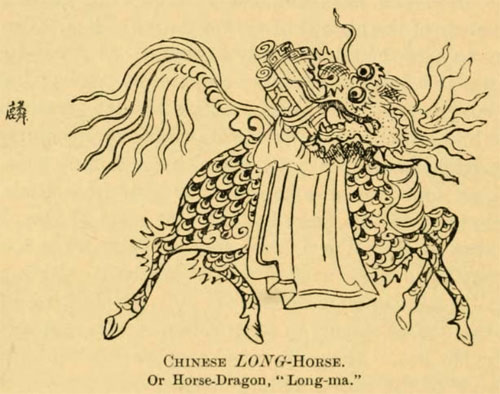

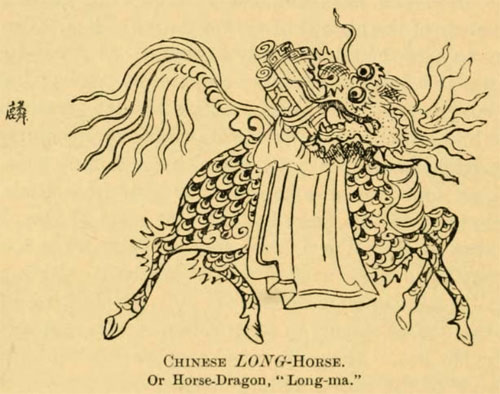

Chinese Long-Horse. Or Horse-Dragon, "Long-ma." The prayer-flags are used by the Lamas as luck-commanding talismans; and the commonest of them, the so-called "Airy horse," seems to me to be clearly based upon and also bearing the same name as "The Horse-dragon" of the Chinese.

Chinese Long-Horse. Or Horse-Dragon, "Long-ma." The prayer-flags are used by the Lamas as luck-commanding talismans; and the commonest of them, the so-called "Airy horse," seems to me to be clearly based upon and also bearing the same name as "The Horse-dragon" of the Chinese.

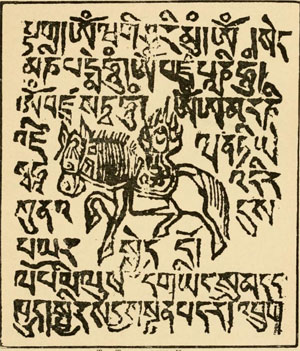

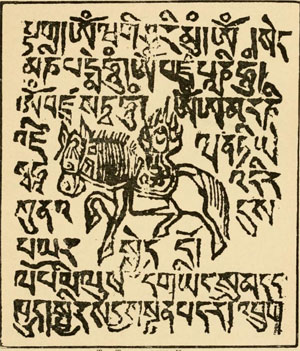

This Horse-dragon or "Long-horse" is one of the four great mythic animals of China, and it is the symbol for grandeur. It is represented, as in the figure on the opposite page, as a dragon-headed horse, carrying on its back the civilizing Book of the Law.  The Tibetan Lung-Horse. Now this is practically the same figure as "The Lung-horse" (literally "Wind-horse") of the Lamaist flag, which also is used for the expressed purpose of increasing the grandeur of the votary; indeed, this is the sole purpose for which the flag is used by the Tibetan laity, with whom these flags are extremely popular.

The Tibetan Lung-Horse. Now this is practically the same figure as "The Lung-horse" (literally "Wind-horse") of the Lamaist flag, which also is used for the expressed purpose of increasing the grandeur of the votary; indeed, this is the sole purpose for which the flag is used by the Tibetan laity, with whom these flags are extremely popular.

And the conversion of "The Horse-dragon" of the Chinese into the Wind-horse of the Tibetans is easily accounted for by a confusion of homonyms. The Chinese word for "Horse-dragon" is Long-ma,59 of which Long = Dragon, and ma = Horse. In Tibet, where Chinese is practically unknown, Long, being the radical word, would tend to be retained for a time, while the qualifying word, ma, translated into Tibetan, becomes "rta." Hence we get the form "Long-rta." But as the foreign word Long was unintelligible in Tibet, and the symbolic animal is used almost solely for fluttering in the wind, the "Long" would naturally become changed after a time into Lung or "wind," in order to give it some meaning, hence, so it seems to me, arose the word Lung- rta,60 or "Wind-horse."

In appearance the Tibetan "Lung-horse" so closely resembles its evident prototype the "Horse-dragon," that it could easily be mistaken for it. On the animal's back, in place of the Chinese civilizing Book of the Law, the Lamas have substituted the Buddhist emblem of the civilizing Three Gems, which include the Buddhist Law. But the Tibetans, in their usual sordid way, view these objects as the material gems and wealth of good luck which this horse will bring to its votaries. The symbol is avowedly a luck-commanding talisman for enhancing the grandeur61 of the votary.

Indian myth also lends itself to the association of the horse with luck; for the Jewel-horse of the universal monarch, such as Buddha was to have been had he cared for worldly grandeur, carries its rider, Pegasus-like, through the air in whatever direction wished for, and thus it would become associated with the idea of realization of material wishes, and especially wealth and jewels. This horse also forms the throne-support of the mythical celestial Buddha named Ratna-sambhava, or "the Jewel-born One," who is often represented symbolically by a jewel. And we find in many of these luck-flags that the picture of a jewel takes the place of the horse. It is also notable that the mythical people of the northern continent, subject to the god of wealth, Kuvera, or Vaisravana, are "horse-faced." -- The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in its Relation to Indian Buddhism, by Luarence Austine Waddell, M.B., F.L.S., F.R.G.S.

This is parallel to what you are doing in dressage. I found that the Shambhala teachings altogether were often applicable to my experience as a dressage rider. In the Shambhala teachings, one of the factors in raising windhorse is that the uplifted quality of lungta arises from applying mindfulness and awareness in everyday life. This lofty quality rests on the foundation of paying attention to every aspect of your life. That is exactly the same as in dressage, and that is what I was learning in such great detail during that early phase in Vienna. I already had some intuitive sense of the possible grandeur and magnificence and power of dressage, but I needed to concentrate on the essentials.

To find the path back to truth, the Germans must simply become mindful of themselves: “This I call a German look, strong, well-bred, and refined,” Rahel said. God and humans, poets and prophets, man and woman call out to the German: be German! The Germans, as a people, are now strong; but “well-bred” only in part, and “refined” even less. – For their education is false, and the false is never refined. He who gives up the invaluable good of his individuality for the cheap finery of a false education is not wiser than the Negro who sells his land and his freedom for a bottle of fake rum and a few beads of glass. Strong, well-bred, and refined – is the character of Bach’s music; with it and towards it the Germans should form themselves; strong, well-bred, and refined – is the content of Rembrandt’s painting; in it the Germans should immerse themselves.

-- Rembrandt as Educator (1890), by Julius Langbehn

It's beyond the scope of this book to go into detail about every aspect of dressage, but I would like to explain some basic principles, which are relevant to training in other disciplines as well. All the movements in dressage are natural movements of the horse. You just harness them. Everything that you see someone do on a dressage horse, with perhaps one exception, the horse will naturally do in the field. For example, horses in a field outdoors will canter a lot and change which leg they are leading with. When you train a horse, you are putting the natural movement in a context, while building up the horse's strength and his ability to understand and move in unity with the rider. If you train your horse incorrectly, which means using undue force, the horse may cease to enjoy his work. He has to be a willing partner. As soon as the horse stops enjoying what he's doing, it becomes very evident: the movement is no longer beautiful. So there's a real psychological aspect to this work. You work with your horse so that his body's fit for what he's doing and also so that he feels good in his mind about it. When those things work together, then you can have a beautiful and harmonious picture. This is, in fact, similar to the principles that one applies in meditation. Meditation works with the natural qualities and habits of mind, gradually building on the student's natural capacity for wakefulness.

In dressage, one of the key principles that you work on developing is collection. Collection is when the horse's energy is gradually controlled without being reduced. A young horse will trot and canter forward with very long strides, and his balance will be a little bit on his forelegs. When you train the horse, you teach him to take more weight on the hindquarters, and the center of gravity will gradually shift backward. Over years, this allows him to have what we call lightness of the forehand. You gradually teach the horse to channel the energy upward and his movement becomes more elevated.

Midway through my training with Kottas, His Holiness the Karmapa visited Vienna. He came to the dharmadhatu to perform the Vajra Crown ceremony while he was in Europe. It was a big to-do. I had a white Mercedes at the time, which I loaned to the dharmadhatu for His Holiness's use during the visit. While His Holiness was visiting, I arranged for him to attend a performance at the Spanish Riding School. I was able to get seats for his party in the Royal Box, which is reserved for special guests. Located underneath the portrait of the Austrian emperor, the Royal Box has upholstered chairs and is the only heated part of the arena. Among all of us in the dharmadhatu, we only had one decent car, the Mercedes, so His Holiness and I both rode in it. Generally, he never rode in a car with a woman because of his monastic vows. However, because I was Rinpoche's wife, he made an exception. (I had already ridden with him in Boulder once before, as he may have remembered.)

I had a mink stole that I was very proud of, and I wore it to the Spanish with an evening gown. We sat together in the Royal Box and watched the performance, which never failed to move me. At one point, His Holiness pointed at my stole and, through his translator, said to me, "So many rabbits died to make that!" I turned to the translator and I said, "Please tell His Holiness, actually it was so many minks." Then His Holiness wanted to know how much it would cost to buy one of the Lipizzaners, the rare breed of horse ridden at the Spanish. I told him it would be about $100,000, and he was somewhat shocked by that.

He enjoyed watching the performance for awhile, but then toward the end, he realized it was time to do his evening meditation, which included a number of chants. It was cold in the box, even with the heat, so he decided that he would also do a meditation practice called tummo, which among other things generates warmth in your body. I was paralyzed with embarrassment as he started to· do his evening practice right there during the performance. Everyone in the arena could hear him chanting. Later, Rinpoche told me I could have told the Karmapa that the program would be over soon and that he could go home and do his practice there. Instead I just sat there, quietly freaking out. At one point, when he was doing his tummo practice, he held my hand for a moment, and his body really was hot, which was kind of amazing. Once again, it was strange to see these worlds of mine coming together, but I survived and in the end, I was delighted that His Holiness had come to the Spanish.