As well, Rinpoche always loved what he called "tent culture." In Tibet, he traveled in caravans from one monastery to the next over a period of days. The monks walked or rode on horseback and at night they camped. He loved this life. It was also how he lived for ten months when he walked out of Tibet. I think, being the person that he was, he had taken something very positive from that long, difficult journey and he wanted to share this outdoor life with his students. A great part of what he brought to the encampment was his appreciation for this. He also found that there were similarities between the military bivouac culture he created at the encampment and the monastic world that he came from. The quality of order and hierarchy applies to both. Rinpoche understood this as the ground of freedom, not the ground of aggression. I think that many of his students came to feel this quite profoundly as a result of the experiences they had at the encampment.

It is by distortedly exalting some men, that others are distortedly debased, till the whole is out of nature. A vast mass of mankind are degradedly thrown into the back-ground of the human picture, to bring forward, with greater glare, the puppet-show of state and aristocracy....

The French Constitution says, There shall be no titles; and, of consequence, all that class of equivocal generation which in some countries is called "aristocracy" and in others "nobility," is done away, and the peer is exalted into the MAN....

If no mischief had annexed itself to the folly of titles they would not have been worth a serious and formal destruction, such as the National Assembly have decreed them; and this makes it necessary to enquire farther into the nature and character of aristocracy.

That, then, which is called aristocracy in some countries and nobility in others arose out of the governments founded upon conquest. It was originally a military order for the purpose of supporting military government (for such were all governments founded in conquest); and to keep up a succession of this order for the purpose for which it was established, all the younger branches of those families were disinherited and the law of primogenitureship set up....

The more aristocracy appeared, the more it was despised; there was a visible imbecility and want of intellects in the majority, a sort of je ne sais quoi, that while it affected to be more than citizen, was less than man. It lost ground from contempt more than from hatred; and was rather jeered at as an ass, than dreaded as a lion. This is the general character of aristocracy, or what are called Nobles or Nobility, or rather No-ability, in all countries....

The two modes of the Government which prevail in the world, are --

First, Government by election and representation.

Secondly, Government by hereditary succession.

The former is generally known by the name of republic; the latter by that of monarchy and aristocracy.

Those two distinct and opposite forms erect themselves on the two distinct and opposite bases of Reason and Ignorance. As the exercise of Government requires talents and abilities, and as talents and abilities cannot have hereditary descent, it is evident that hereditary succession requires a belief from man to which his reason cannot subscribe, and which can only be established upon his ignorance; and the more ignorant any country is, the better it is fitted for this species of Government.

On the contrary, Government, in a well-constituted republic, requires no belief from man beyond what his reason can give. He sees the rationale of the whole system, its origin and its operation; and as it is best supported when best understood, the human faculties act with boldness, and acquire, under this form of government, a gigantic manliness....

When men are spoken of as kings and subjects, or when Government is mentioned under the distinct and combined heads of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, what is it that reasoning man is to understand by the terms? If there really existed in the world two or more distinct and separate elements of human power, we should then see the several origins to which those terms would descriptively apply; but as there is but one species of man, there can be but one element of human power; and that element is man himself. Monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, are but creatures of imagination; and a thousand such may be contrived as well as three....

As to the aristocratical form, it has the same vices and defects with the monarchical, except that the chance of abilities is better from the proportion of numbers, but there is still no security for the right use and application of them.*[17]

Referring them to the original simple democracy, it affords the true data from which government on a large scale can begin. It is incapable of extension, not from its principle, but from the inconvenience of its form; and monarchy and aristocracy, from their incapacity. Retaining, then, democracy as the ground, and rejecting the corrupt systems of monarchy and aristocracy, the representative system naturally presents itself; remedying at once the defects of the simple democracy as to form, and the incapacity of the other two with respect to knowledge....

The fraud, hypocrisy, and imposition of governments, are now beginning to be too well understood to promise them any long career. The farce of monarchy and aristocracy, in all countries, is following that of chivalry, and Mr. Burke is dressing for the funeral. Let it then pass quietly to the tomb of all other follies, and the mourners be comforted.

-- Rights of Man, by Thomas Paine

For me, these same years were also a time of committing myself to a discipline that had been firmly rooted for centuries in the life of the nobility in Europe. It was the kings and queens of Europe who kept dressage horses and built the great arenas for them to perform in. So, strangely enough, although I was away for much of the developing years of Rinpoche's Shambhala vision, I was also immersed in a regal training, of sorts.

In October 1978, I returned to the United States for the first Kalapa Assembly, the first large Shambhala program for the presentation of the most advanced Shambhala teachings. In this situation, as he had done in travelling through Nova Scotia, Rinpoche insisted that everything be conducted in a court mandala, with all of us living together in the Kingdom of Shambhala, but in Snowmass, Colorado! He presided over the assembly as the Sakyong, the ruling monarch of Shambhala, and I was at his side as the Sakyong Wangmo.

The first assembly was held in the same hotel in Snowmass where two of the earliest seminaries had taken place. Because the hotel could only hold about a hundred people, the assembly was divided into two two-week sessions, as there were now around two hundred people practicing the Shambhala teachings at the highest level. The whole program lasted for a month.

Rinpoche gave seventeen talks over the month, which was about one every other night. There was meditation practice during the day, people attended discussion groups, and then there were formal dinners, banquets, and a number of ceremonies. One of the highlights was a troupe of bugaku dancers performing an ancient repertoire of dances of the imperial court of Japan, who happened to be touring the United States at this time.

Bugaku Dance at Kurama dera in Kyoto.

The imperial way is the Great Way that the emperor has graciously bestowed on us to follow. For this reason, it is the Great Way that the multitudes should follow. It is the greatest way in the universe, the true reality of the emperor, the highest righteousness and the purest purity .... The imperial way is truly the fundamental principle for the guidance of the world. If the people are themselves righteous and pure, free of contentiousness, then they are one with the emperor; and the unity of the sovereign and his subjects is realized.

Is there anything that can be depended on other than the emperor's way? Is there a secret key to the salvation of humanity other than this? Is there a place of refuge other than this? The emperor should be revered for all eternity. Leading the masses, dash straight ahead on the emperor's way! Even if inundated by raging waves, or seared by a red-hot iron, or beset by all the nations of the world, go straight ahead on the emperor's way without the slightest hesitation! This is the best and shortest route to the manifestation of the divine land [of Japan].

The emperor's way is what has been taught by all the saints of the world. Do not confuse the highest righteousness and the purest purity with mere loyalty to this person or that, for only those who sacrifice themselves for the emperor possess these qualities. This is the true meaning of loyalty and filial piety....

The underlying assumption of the "imperial way" was that the nation is in essence a patriarchal family with the emperor as its head. It was taken for granted that individuals exist for the nation rather than the other way around. Equally important was the assumption that some men are born to rule while others are to be ruled because men are by nature unequal.

-- The Emergence of Imperial-State Zen and Soldier Zen [Chapter Eight], [Excerpt] from "Zen at War", by Brian Daizen Victoria

Rinpoche's lectures reminded me in a way of the first seminary, in that he was giving an overview of the entire Shambhala path, and he was pouring both information and emotion into his talks. He was sharing his heart of hearts with people, trying to give us the essence of his understanding of the Shambhala teachings. That aspect I found magical and wonderful.

I was not so enamored of other things. I could see the point of Rinpoche as Sakyong; he was transmitting the wisdom of Shambhala to people, and I saw him as a unique human being. I thought that there should be an acknowledgment of his leadership and the wisdom that he embodied. Seeing him as the Sakyong, a spiritual king and protector of the earth, was not difficult for me. However, I couldn't understand why we were building up so many other people, putting them into positions that I thought were rather bogus. What was the point of having all these lords, ladies, ministers, and generals?

So at the beginning of the first assembly, I was quite uncomfortable. Actually, a lot of the participants were having quite a hard time adjusting to this new Shambhala world. I was certainly not the only one. Everybody was calling me "Your Highness." I had Dorje Kasung members accompanying me wherever I went, and Rinpoche wanted me to have my own personal attendants and all the rest of it. I found it incredibly awkward and unsettling to land in the middle of this heightened environment and to have to function in that world. I trusted him fundamentally, but I thought things had gone crazy. Actually, in some ways, from a conventional point of view, things had gone crazy and I was expected to uphold this crazy world! It was one thing to adjust to it, but I was actually supposed to be a spokesperson for what was happening.

I remember the day that this all came out. He and I were together in the suite at the hotel, and I broke down crying at some point. We were out on the balcony of the suite, which was on the roof of the hotel. Things were overwhelming to me. He sat down with me and started to explain his thinking. He was very sweet.

I think it was a hallmark of the way Rinpoche taught that he always appreciated something about a situation. Even in the worst of the worst conditions, he could always find wisdom. In this case, he started describing his appreciation for Mao Tse-tung. In spite of the devastation Mao had wrought in Tibet, Rinpoche admired certain aspects of his approach. Only someone with such a big mind, like Rinpoche, could appreciate someone like Mao, who had done these awful things that had destroyed Rinpoche's life in Tibet. He described to me how Mao Tsetung proceeded when he decided he was going to conquer China. The first thing he did was to create the complete structure for the future government. Rinpoche said that Mao understood that when you attain power, there's a lot of chaos. You prepare for that future transition by having a structure in place that can function when things change. Rinpoche said that this applied to what we were creating with Shambhala; we had to plan for the chaos. If nothing else, Rinpoche had to plan for his own death. He wanted the people he was training to be prepared to go forward after his death and to have a big view of their responsibility and their duty in the future. He wanted to put them into positions of responsibility now so they would be fully trained and able to function after he was gone.

He explained to me that the future of the dharma in the West would inevitably involve pain and chaos. He thought it was quite sensible, in a strange way, to draw on Mao's approach. And you know, I actually could accept this. It made sense to me because I could see that the way he was working with people was preparing them to take on more responsibility, either within Vajradhatu or the larger society. You could see that people were becoming much more tamed and much more commanding at the same time. At that point, I was more able to relax and accept the situation.

After we talked, things seemed better to me. I decided that we weren't really nuts, although we were decidedly eccentric. What we were doing had a purpose that was founded in truth. Rinpoche also said that he was trying to provide an example for people, a structure for them to learn how to be, in ways that would be helpful to them. He talked about the importance of manifesting Shambhala society within our day-to-day lives. He was always thinking about how he could bring more people in and how he could work with people in an intimate way.

While I could accept this intellectually, it was extremely difficult for me to accept a total lack of freedom in my everyday life, which my role implied. Whenever I was living in Rinpoche's world, there was absolutely no break, no time off, so to speak. For so many years, even my bedroom wasn't my own. My attendants would come in and out of the bedroom all the time, and I was expected to be kind to them. There were constantly other people in the house. If I went into my kitchen, there were always other people there, even at three A.M. Although people were polite to me, there were people serving at the Court, especially men, who didn't understand what I needed for my children and myself. One of the reasons I was so upset, even in 1978, was that I could see that becoming the Sakyong Wangmo meant the complete relinquishment of my freedom, and that was extremely difficult for me to accept. Rinpoche was asking me to do what he had done, which was to accept having no privacy. Even now, I find this difficult. I have my own life, but when I go to programs with the Shambhala community, after three days, I think, "I'm so glad I don't live like this all the time!"

I gained some insight into how Rinpoche lived his whole life when I went to Tibet after his death. I saw that many of the teachers there live this way. They are completely accessible. People just come into a teacher's room unannounced all the time. I realized that this was how Rinpoche grew up -- without any understanding of what privacy meant. He belonged to the people. Maybe it's easier if you've grown up in that environment.

It was, however, a big jump for me. Rinpoche wasn't any longer just the Buddhist teacher going into his office and giving talks. He was essentially asking me and his whole family to join him in this new teaching adventure. He was asking me to also take on a role and to train people as well as train myself. Now it wasn't just that he wanted me to put up with students being around all the time. He also wanted me to think of myself as a teacher or a role model in the Court. It was intense and challenging. At the same time, it was remarkable, given his upbringing and his culture, that he wanted to offer such respect and responsibility to a woman. He had developed tremendous respect for women, and proclaiming my role as the Sakyong Wangmo was a way of expressing that.

Rinpoche told me that I was him, basically, that we were one mind. He said that I was the feminine representation of the Sakyong. He told me that I had the responsibility of nurturing the feminine in our world: the cultural and enriching aspects of the kingdom. He said that we had to work together as a team and therefore that he wanted to put me on the same elevation as him. In my role as Sakyong Wangmo, I was given the responsibility to create our kingdom's culture.

In the 19th century, American and British women's rights—or lack of them—depended heavily on the commentaries of William Blackstone which defined a married woman and man as one person under the law. Here's what William Blackstone wrote in 1765:By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband; under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs every thing; and is therefore called in our law-French a feme-covert, foemina viro co-operta; is said to be covert-baron, or under the protection and influence of her husband, her baron, or lord; and her condition during her marriage is called her coverture. Upon this principle, of a union of person in husband and wife, depend almost all the legal rights, duties, and disabilities, that either of them acquire by the marriage. I speak not at present of the rights of property, but of such as are merely personal. For this reason, a man cannot grant anything to his wife, or enter into covenant with her: for the grant would be to suppose her separate existence; and to covenant with her, would be only to covenant with himself: and therefore it is also generally true, that all compacts made between husband and wife, when single, are voided by the intermarriage. A woman indeed may be attorney for her husband; for that implies no separation from, but is rather a representation of, her lord. ....

-- The Blackstone Commentaries and Women's Rights, by Jone Johnson Lewis

That was what I was working with during the first Kalapa Assembly, and that was a huge leap for me at that point. On another very personal level, there was another big development in my life at this time. I became romantically involved with Rinpoche's doctor, Mitchell Levy, during the first assembly.

Before the assembly started, I was in Boulder with Rinpoche for a little while. It was the first time I had seen the new Kalapa Court, located at the corner of Eleventh and Cascade in Boulder. The house on Mapleton had proved too small for all of us, so we had found a new house, which was renovated over the summer of 1978. Rinpoche was able to move into the new Court a little while before the assembly started. He was anxious to share it with me. He and the Regent had worked together on the furniture and the interior decoration with various other people in the sangha, such as Robert Rader, a talented interior designer.

The new Court had much more light and a wonderful feeling to it, and it had more room for everyone, along with a beautiful garden. It was where we lived in Boulder until we moved to Nova Scotia in 1986, and it worked quite well for us. In the beginning, Rinpoche and I had a bedroom with a sitting room attached to it, and the Regent and Lila, who was now Lady Rich, were next door to us. Osel also had a bedroom on the same floor upstairs. Down the hall were rooms for Vajra and Anthony, the Regent's children, and a room for Gesar. The living room downstairs had blue rugs that had dragon designs cut into them. They were custom-made for the Court, and they were supposed to be very special, but they didn't turn out so well. I used to call them the bath mats, which Rinpoche hated. All in all, however, the new house was a great improvement.

When I got home, I had a bad cough, and I was sure that I had bronchitis. I had a tendency to get respiratory infections at that time because I smoked. The night I got in from Vienna, Rinpoche and I had dinner together, and I was coughing a lot, so he suggested that I go downstairs and see his doctor, who was hanging out in the basement. The new Court had a full, finished basement on the ground floor, with quite a lot of light, so it was much improved over the old house. John Perks and his wife Jeannie lived there; Shari and Bob also lived in the basement, and soon Walter and Joanne Fordham also joined us as part of the live-in Court staff. The people who had these live-in positions were close students and friends, not servants in the traditional sense. Rinpoche's lineage is called the Trungpa lineage, and in Tibetan trungpa means one who is close to the teacher, which basically means "servant." It is quite a desirable thing in this lineage to serve the teacher because this is how you receive the most intimate training.

In addition to bedrooms, offices, and a staff living room in the basement, the Court also included a little carriage house where various staff people lived over the years. During certain periods, John Perks organized staff dinners, which took place in the basement either before or after the family ate. It was quite a nice setup and a lot of socializing in the house went on down there.

In any case, I went down to the basement and looked around and finally found this young Jewish gentleman, whom I'd never met before. This was Dr. Levy. He had a great deal of hair at that time; it almost looked like he had an Afro. I told him that Rinpoche had sent me to see him and that I had bronchitis. He told me, "I hate patients who diagnose themselves." Then he listened to my chest and said that he didn't think that I had bronchitis, and I was probably okay. I insisted that I had bronchitis, and he got a bit pissed off. There was chemistry between us right from the start.

I proceeded to go on up to the assembly, where I became increasingly ill. Mitchell came to see me again and realized that I actually did have bronchitis. In the course of treating my illness, we developed a liking for one another. In addition to being Rinpoche's doctor, Mitchell was also one of his main attendants, or kusung. Rinpoche liked having him around, so Mitchell was there a lot. He was in the suite all day. After I got to know Mitchell, I developed a real crush on him. Finally, I confessed to Rinpoche that I wanted to sleep with his doctor. Rinpoche thought that was a great idea. He told Mitchell that he should ask me out on a date. Mitchell had only been married a few months, so this idea freaked him out quite a lot at first. At the same time, he and his wife had what you would call an open relationship; but he still hesitated. Finally, he decided that he'd like to spend time with me, so he asked me out and that's how we got together.

I suppose this sounds like it was a quite casual arrangement, which might be shocking to people. At the beginning, I did think of it as a casual liaison. My husband, as many people knew, had a great number of girlfriends. It was something that I accepted, and perhaps because that was our arrangement, I also had the occasional indiscretion myself. In my case, there were not many of them, and they didn't have a great deal of meaning to me. Sleeping with somebody else had been an expression of friendship, and of course of youthful passion. I imagined that spending time with Mitchell would be the same. But that was not at all the case. From the very beginning, I had a special connection with him. At that assembly, we spent a fair amount of time together. By the end, we developed a strong bond, and I was falling in love with him. Rinpoche didn't seem to have a problem with it at all, at least not at that time. It got a little bit rockier later.

I didn't exactly think that I was having an affair. I didn't conceptualize the relationship much at that time. It was just what was happening. Mitchell's wife, Sarah, knew what we were doing. In my mind, I figured everything was okay. I was married to Rinpoche, and Mitchell was married to Sarah. Mitchell and I had a nice relationship too, and it was going to be fine. I suppose it was a little naive on my part.

For the next two years, while I was living in Vienna, Mitchell and I saw each other whenever I was back in Boulder. When I was in town, we would spend about one night a week together. It seemed to be fine with everybody. It was, more or less, completely agreed upon. I adored Mitchell. I loved him. I found that there was great communication between us.

For me, one offshoot of the creation of the Court was that, in general, I found myself emotionally isolated from people. Having friendships with people was quite loaded in some ways. I had only a very few close friends. Other relationships seemed to be clouded by people having an agenda of personal gain. It was difficult to get away from that. I found that it was rare that I could have a relationship that didn't come with a lot of baggage.

My life was quite lonely at times. I felt a separation between me and the rest of the sangha, with me being the Sakyong Wangmo and being served and all of that. I imagine that my experience was somewhat like the queens of old. On some level we had recreated that culture. I felt that I had a fresh relationship with Mitchell, one completely outside of all of that. With him, I could really be who I was. I could share things with him, and I felt that he understood me better than almost anyone, except Rinpoche. My relationship with Mitchell gave me something to look forward to when I came home. As well, I could share my whole crazy life with him, without having to edit anything or hold anything back. I found that quite freeing. We shared a lot of the same perceptions, which was extremely helpful.

So this year, 1978, proved to be a watershed in our lives. After the Kalapa Assembly, I returned to Vienna. According to the Shambhala calendar, which we began to use in our community during this era, the new year usually comes in late January or February. The ten days at the end of the year are supposed to be a very tricky time, filled with obstacles. 1978 and early '79 was the Year of the Earth Horse, interesting for me because I was so involved with the horse world at this time. The very end of 1978 was when I had my automobile accident, which certainly seemed inauspicious. Because of this occurrence, I couldn't return to Boulder for the celebration of the New Year.

During the period that I was recuperating, Rinpoche phoned me several times a week to see how I was doing. In the middle of January, Rinpoche phoned me to tell me about a crisis involving the Vajra Regent. Since Rinpoche's return from Charlemont the previous year, the Regent had continued to manifest a lot of heavy-handedness and arrogance. He had moments when he really shone, and he worked extremely hard to grow into his role as Regent, but he also had a kind of street fighter's mentality that dumped a lot of aggression on others at times. More than that, he seemed to get carried away with who he was. In the fall of 1978, Rinpoche and the Regent taught several meditation programs together called "Transforming Confusion into Wisdom." They taught one in Boston and one in Los Angeles. The title of the seminar seemed to exemplify what Rinpoche was hoping could be accomplished in working with his Regent, Osel Tendzin.

By January 1979, while I was recovering from my accident, things were getting out of hand. One night Rinpoche attended a birthday party for Ken Green, who was a member of the Vajradhatu board. During the party, several board members took Rinpoche aside and began complaining to him about the Regent's conduct and their fears that he was becoming an egomaniac. On the spot, Rinpoche called a late-night meeting of his board of directors at the Kalapa Court to discuss the issues involving the Regent and his abuse of power. All the members of the board, as well as the two dapons, were summoned. David Rome was the chairman of the board, in addition to his other duties, and he also attended. That night, the Regent was at a private house party for gay men across town. Even before he and Lila moved into the Court with us, I became aware that the Regent was interested in men as sexual partners. He was, at the very least, bisexual.

It's probably important to clarify that Rinpoche did not have a problem with the Regent's sexual orientation per se. He was concerned with whether the Regent treated others properly, regardless of the sexual politics. Rinpoche had himself been concerned about the Regent's arrogance for some time, and that night in January he decided that it was time to do something about the situation. He called over to the party to tell the Regent to come to the Court to join the meeting. When the Regent didn't appear, Rinpoche sent Dapon Gimian to find the Regent and tell him to return to the Court right away. The Regent didn't appear for another hour.

When the Regent finally arrived, Rinpoche tried to get the board of directors to confront the problems with the Regent. They were all gathered in the blue room, the room with the blue rugs, in the Court. Rinpoche asked various members of the board to address the Regent directly and to say what they thought the problem was. Apparently, as Rinpoche told me later, the members of the board were rather feeble in their statements. After some time, Rinpoche said good night and went upstairs. Most of the board members left, but several people stayed behind to review what had happened. At that point, nothing had been resolved. Those who remained were David Rome, the Kasung Kyi Khyap; Jim Gimian, the Kasung Dapon; Lodro Dorje [Eric Holm], who was the head of practice and study and had the title of Dorje Loppon; and Michael Root, the Regent's chief of staff. The Regent was also there. Rinpoche sent John Perks down to ask everyone downstairs to join him.

They went upstairs to Rinpoche's sitting room, where he suggested that they all drop acid together. When Rinpoche had given bodhisattva vows earlier that month, a student had presented him with quite a large vial of LSD as a gift. As part of taking the bodhisattva vow, you give something to the teacher that symbolizes surrender to you. For this student, giving up drugs was that gesture. Rinpoche had held onto the vial of LSD, and he produced it for this occasion.

Rinpoche asked John Perks to be the attendant for the night, so John didn't take LSD. He was there to take care of everybody. As the LSD started to take effect, the Regent started to manifest more and more in a caricatured feminine way, as a woman. He was apparently quite outrageous and somewhat sleazily seductive, fawning over Rinpoche and the others. Rinpoche was trying to talk to him about the problems with his comportment as the Regent, but the Regent was quite out of it, and didn't seem able to hear what Rinpoche was saying at all.

At one point Rinpoche decided to phone me and asked me to talk to the Regent. (By the way, Rinpoche didn't change at all when he took LSD. Not one bit, although he understood completely what other people experienced on drugs.)

So I left to go to India, and I took a bottle of LSD with me, with the idea that I'd meet holy men along the way, and I'd give them LSD and they'd tell me what LSD is. Maybe I'd learn the missing clue....

At one point in the evening I was looking in my shoulder bag and came across the bottle of LSD.

"Wow! I've finally met a guy who is going to Know! He will definitely know what LSD is. I'll have to ask him. That's what I'll do. I'll ask him." Then I forgot about it.

The next morning, at 8 o'clock a messenger comes. Maharaji wants to see you immediately. We went in the Land Rover. The 12 miles to the other temple. When I'm approaching him, he yells out at me, "Have you got a question?"

And I take one look at him, and it's like looking at the sun. I suddenly feel all warm.

And he's very impatient with all this nonsense, and he says, "Where's the medicine?"

I got a translation of this. He said medicine. I said, "Medicine?" I never thought of LSD as medicine! And somebody said, he must mean the LSD. "LSD?" He said, "Ah-cha -- bring the LSD."

So I went to the car and got the little bottle of LSD and I came back.

"Let me see?"

So I poured it out in my hand "What's that?"

"That's STP ... That's librium and that's ..." A little of everything. Sort of a little traveling kit.

He says, "Gives you siddhis?"

I had never heard the word "siddhi" before. So I asked for a translation and siddhi was translated as "power". From where I was at in relation to these concepts, I thought he was like a little old man, asking for power. Perhaps he was losing his vitality and wanted Vitamin B 12. That was one thing I didn't have and I felt terribly apologetic because I would have given him anything. If he wanted the Land Rover, he could have it. And I said, "Oh, no, I'm sorry." I really felt bad I didn't have any and put it back in the bottle.

He looked at me and extended his hand. So I put into his hand what's called a "White Lightning". This is an LSD pill and this one was from a special batch that had been made specially for me for traveling. And each pill was 305 micrograms, and very pure. Very good acid. Usually you start a man over 60, maybe with 50 to 75 micrograms, very gently, so you won't upset him. 300 of pure acid is a very solid dose.

He looks at the pill and extends his hand further. So I put a second pill -- that's 610 micrograms -- then a third pill -- that's 915 micrograms into his palm.

That is sizeable for a first dose for anyone!

"Ah-cha,"

And he swallows them! I see them go down. There's no doubt. And that little scientist in me says, "This is going to be very interesting!"

All day long I'm there, and every now and then he twinkles at me and nothing -- nothing happens! That was his answer to my question. Now you have the data I have.

-- Be Here Now, by "Ram Dass," aka The Lama Foundation

Rinpoche said to me, "Sweetheart, I need your help. I need you to talk to the Regent. You have to bring him back. Make him understand what's happening." So Rinpoche passed the phone to the Regent and said, "Here's Diana to talk to you." For some reason, the Regent refused to believe that it was me. He kept saying, "Jane, is that you? Is that you, Jane?" I kept telling him that he should listen to what Rinpoche was saying to him, and that he should remember who he was. But he couldn't hear me at all. He passed the phone back to Rinpoche, saying, "That isn't Diana. That's Jane. I don't know what you're talking about."

After I hung up, still unable to get the Regent's attention, Rinpoche smashed his hand down on the coffee table in our sitting room at the Court and screamed "NO!!!!!!!!!!!" I heard that it was earsplitting. He put a dent in the table with his hand. Finally, he got through, and the Regent crumpled at his feet. Rinpoche placed his hands together in front of the Regent's face. He held up his two hands, cupping them as if they were holding a treasure. Indicating the space between his hands, with everyone as witnesses, he said to the Regent, "This is the dharma. This is unbelievably precious. And if you pervert the dharma, I will destroy you. You have to understand that I made you, and I can destroy you."

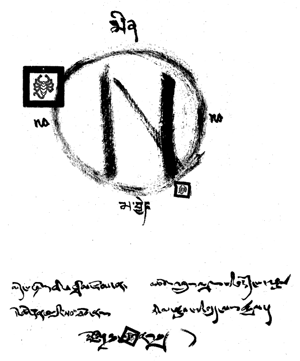

It was a very heavy message. After Rinpoche lowered the boom, so to speak, the Regent was a mess, and he became much more gentle and humble. He sat at Rinpoche's feet and tried to pull himself together. A few hours later, Rinpoche said that he wanted the wives of all of the people who were there to come over. Everybody phoned their spouses, who provided more witnesses to what was going on. When the ladies arrived, Rinpoche didn't say too much about what had happened. He asked everyone to join him downstairs in the front hallway of the Court. He said that he wanted to do a calligraphy to mark this occasion. He had a huge calligraphy brush that was kept on a shrine in the house. He asked for the brush to be brought into the hallway, along with a bowl of black sumi ink. He also asked for a long roll of paper, which was unrolled and spread out to give him room to do the calligraphy. Then, with everyone gathered around him, he made a huge slashing stroke with the brush and screamed the word NO again. Ink went everywhere. The entire hallway had to be repainted, and everyone's clothing was splattered with ink. It was a deafening message. At the end of the year, Rinpoche did another calligraphy for the Regent, which is made up of the word no, with the N inside of the O. At the end of 1980, Rinpoche wrote a poem about what he called the "Big No." Later, in 1982, he talked about the experience when he was conducting a Shambhala Training in Boulder. His talk was on the subject of self-deception. He said:

The antidote to a setting-sun mentality is to be free from deception. In connection with that, I'd like to tell you about the Big No, which is different than just saying no to our little habits, such as scratching yourself like a dog. When we scratch ourselves, we try to do it in a slightly more sophisticated way. But we're still scratching, and there is a limit: we have to learn how to be human, as opposed to how to be an animal.

The Big No is a whole different level of no. I think it's public knowledge; anyway, you should know that my Vajra Regent and I took LSD at the Kalapa Court, my house, some time ago. The concept of the Big No became the main point of our trip; That No is that you don't give in to things that indulge your reality. There is no special reality beyond your reality. That is the Big No, as opposed to the regular no.

The ordinary Shambhala type of no applies to things like not scratching yourself or keeping your hair brushed. That no brings a sense of discipline, rather than constantly negating you. In fact, it's a yes, the biggest yes.

When we took LSD together, the Big No came out. Everybody was indulging in their world so much. So how to say no? I had to crash my arm and fist down on my coffee table and break it. I painted a giant picture in the entrance hall of my house. Big No. From now onwards it's NO. Later on, I executed another calligraphy for the Regent as another special reminder, which he has in his office. If you want to look at it, you can. You can look at no no.

You cannot by any means, for any religious reasons or for any spiritual metaphysical reasons step on an ant or kill your mosquitoes -- at all. That is Buddhism. That is Shambhala. You cannot destroy life. We have to respect everybody. You cannot make a random judgment on that at all. That is the rule of the king of Shambhala. You can't act on your desires alone. You have to think, contemplate, the details of what needs to be removed and what needs to be cultivated. It's up to you.2

That message meant a great deal to him. It was meant not just for the Regent but also for all of his students. By the way, when this talk was published in the book Great Eastern Sun, we decided not to mention the LSD because it seemed unnecessary. But at this time, I feel that I have to tell the whole truth. Rinpoche didn't take drugs a lot; he used them very occasionally to break through with people who were particularly stuck. That was usually when he employed something like LSD.

His dalliance with Western pharmaceuticals soon blossomed into full-fledged addiction that clouded his judgment. Although his drinking and sexual exploits were never kept secret, his staggering coke habit was well concealed from his students....

In the end, the final proclamation of a guru’s worth can be found in his students. Those who remain loyal to Rinpoche’s vision display the pathetic lack of identity found in every cult. They are unhappy pod people who toast his posthumous brilliance with pretentious, self-aggrandizing platitudes. Denying his abuse of power and his rampant addictions (a $40,000-a-year cocaine habit, along with a penchant for Seconal and gallons of sake), they exhibit symptoms of untreated codependents.

-- The Other Side of Eden: Life With John Steinbeck, by John Steinbeck IV & Nancy Steinbeck

Yes, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche used cocaine -- a lot. Although there are people who have publicly talked about this using their real names, most of us 'in the know' don't for several reasons. First, cocaine is highly illegal. We don't want our names forever attached to cocaine and CTR on the internet. We have private lives, and don't want our kids, clients, and colleagues to know we were involved with cocaine (or that we stood on the sidelines as we watched our then-guru sniff and drink himself to death). Second, we don't want to be trolled by current Shambhala members, some of whom have voracious appetites for denial-fueled revenge. Current practitioners want to believe that CTR was upfront with everything he did, and they cite his horrific alcoholism and womanizing as examples of things he did not hide. So the realization that he was indeed a regular cocaine user -- and one who was not upfront about this -- rubs harshly against the myth of his openness. Another thing to keep in mind when trying to get info on this is that not a lot of people were aware of his cocaine use. His inner circle put forth considerable effort -- frequently laced with lies -- to conceal this. In any case, enough people did see it and I think in the future you'll find more and more people coming forward.

-- Prasunya, Reddit

One day I arrived at the court for a shift and I was told I was to receive another transmission from Marty Janowitz. I assumed this was to be like the others, perhaps he was giving me TGS transmission early. Marty told me this transmission was extremely sacred and was only known to a few close students. He then pulled out a vial filled with a white powdery substance. Marty told me it was ground up vitamin D or something. (I really can’t remember exactly what he said it was). He put a bit of it on the spoon and told me to rub it on my gums, which I did. It was not cocaine. It was part of our job description to always carry a vial of “Tabi” which was the code name for cocaine. Due to his paralysis, CTR only had the use of one hand, so when he called for tabi it was our job to go into the bathroom with him, keep him steady, help him get his penis out before he wet his pants and put the coke on a spoon for him to inhale. It was also our job to keep his nose clean, and as you can tell from the picture, we were not always successful. Later, when I went to the bathroom alone, I put some on my gums. It was definitely cocaine.

This is another secret I have kept for over 30 years. I can no longer keep it. I believe it is not of benefit to anyone to keep this secret anymore. I believe it’s important for the followers of Shambhala to know what really happened in the “inner circle” of the court. We all -- every one of us -- didn’t know how to say “no” to CTR. We were so busy tripping over each other to do his bidding that we never questioned why an enlightened mediation master would need copious amounts of cocaine and alcohol every day. We never questioned why he spoke of every woman or young girl in sexual terms. It was supposed to be a great honor to sleep with him. No one wondered if his sexual appetite for his female students might be unhealthy.

-- The first time I met His Majesty Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, by Leslie Hays

Maybe anyone put in the Regent's position would have gone through a period of being bloated like this. Certainly, everyone has plenty of self-deception to work through. But in the Regent's case, it was extreme, and I think Rinpoche felt that this was a kill or cure situation. It was his lineage that was at stake here, the depth of the teachings that he wanted to ensure would remain intact after his death. He was counting on the Regent to carry that forward, and I think that already by this time, Rinpoche had serious doubts that the Regent could carry this load.

After the Big No acid trip, Rinpoche and the Regent went on a vacation together to the house in Pitzcuaro where we usually stayed. They spent about ten days together, along with some other people who Rinpoche invited along, including Dapon Gimian and his wife. The Regent was very meek and gentle during that time, Rinpoche told me, but the real question was: Would it last? Would it take?

With these events, the Year of the Earth Horse came to an end in the Shambhala world. The last day of the year, February 26, 1979, there was a full solar eclipse. It was the last full eclipse of the millennium that was visible from the continental United States.

If you know "Not" and have discipline,

Then the ultimate "No" is attained,

Patience will arise along with exertion.

And you are victorious over the maras of the setting sun.

How to Know No

There was a giant No.

That No rained.

That No created a tremendous blizzard.

That No made a dent on the coffee table.

That No was the greatest No of No's in the universe.

That No showered and hailed.

That No created sunshine, and simultaneous eclipse of the sun and moon.

That No was a lady's legs with nicely heeled shoes.

That No is the best No of all.

When a gentleman smiles, a good man,

That No is the beauty of the hips.

When you watch the gait of youths as they walk with alternating cheek rhythm,

When you watch their behinds,

That No is fantastic thighs, not fat or thin but taut in their strength, Loveable or leaveable.

That No is shoulders that turn in or expand the chest, sad or happy,

Without giving in to a deep sigh.

That No is No of all No's.

Relaxation or restraint is in question.

Nobody knows that big No,

But we alone know that No.

This No is in the big sky, painted with sumi ink eternally.

This big No is tattooed on our genitals.

This big No is not purely freckles or birthmark,

But this big No is real big No.

Sky is blue,

Roses are red,

Violets are blue,

And therefore this big No is No.

Let us celebrate having that monumental No.

The monolithic No stands up and pierces heaven;

Therefore, monolithic No also spreads vast as the ocean.

Let us have great sunshine with this No No.

Let us have full moon with this No No.

Let us have cosmic No.

The cockroaches carry little No No's,

As well as giant elephants in African jungles --

Copulating No No and waltzing No No,

Guinea pig No No.

We find all the information and instructions when a mosquito buzzes.

We find some kind of No No.

Let our No No be the greatest motto:

No No for the king;

No No for the prime minister;

No No for the worms of our subjects.

Let us celebrate No No so that Presbyterian preachers can have speech impediments in proclaiming No No.

Let our horses neigh No No.

Let the vajra sangha fart No No --

Giant No No that made a great imprint on the coffee table.3