A few weeks later, I decided to go up to see Rinpoche again. Unless your parents made special arrangements, on weekends you were expected to stay at school. My mother, of course, had no idea what I was up to and hadn't given her permission for me to go anywhere, but I decided to leave school for the weekend anyway. This time, I didn't cover my tracks so well. I just split.

My mother wouldn't give me any spending money because she thought that I would use it to buy drugs. So there I was in the south of England, and I had to find a way to get up to Scotland without any cash. I called Rinpoche, and he said that if I could get to the Carlisle train station, which was the station nearest to Samye Ling, he would pay for my taxi the rest of the way.

I hitchhiked part of the way up to Scotland. A truck driver picked me up ~d drove me all the way up to Yorkshire. There I boarded the train to Carlisle. In England in those days, you had to give your ticket to the conductor at your destination. Since I had no ticket, I waited until the train slowed down coming into Carlisle Station, and I opened the door and jumped off the train. I remember hitting the ground with a big thonk and rolling down an embankment. Then I had to climb over several fences, which led me into a chicken farm. There were hundreds of chickens running around in the yard. When I got out of the farm, I walked around to the front of the train station, relatively unscathed, and took the hour-long taxi drive up to Garwald House. Rinpoche, as he'd promised, paid for the taxi.

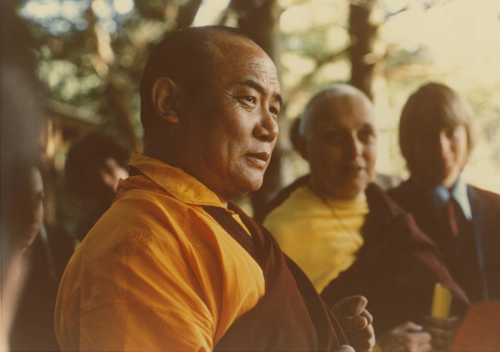

We had a fabulous weekend together. It only deepened my connection with him, and we were able to talk about a lot of things. I had some questions about our relationship and whether it was appropriate for a Tibetan lama to be sexually active. When Rinpoche and I were in bed together that second weekend, I said to him, "You know, I thought sex was bad, especially for people like you." I told him that I'd heard that the Dalai Lama had spoken about the value of sexual abstinence. Rinpoche told me that was true for some people, but that it wasn't true for everyone. He pointed out to me that he was no longer a monk.

In Tibetan Buddhism there is quite an old established tradition of married lamas, who can be revered spiritual teachers. Khyentse Rinpoche, one of my husband's main mentors, was one of these married teachers. It is often the case, for some reason, that tertons marry. When Rinpoche began finding hidden treasures, terma, in Tibet, some of the older monks at his monastery speculated that he might take a consort in the future.

Speaking more broadly, I believe that sexuality is viewed differently in Buddhism than it is within the Judeo-Christian tradition. I think that many Oriental teachers who've come to the West have hidden their views on sex from their Western disciples because they've realized that these attitudes, which are cultural as well as religious, would be misconstrued. Some Western adherents of Buddhism advocate a very conservative, almost moralistic, approach, but that doesn't come from the Buddhist tradition itself. There is, of course, an emphasis on not causing harm to others, which applies to one's sexual behavior as well as to other < areas of conduct. But that doesn't mean that one must have a prudish approach toward sex.

In any case, Rinpoche and I spent the entire weekend in bed together, just as we had the first time we were together. I can remember lying awake one of the nights that I was there feeling how special it was to be with him. I was very much in love. The time went by quickly, and I was sad to have to leave. When I had to go, Rinpoche found someone to drive me partway, and then I hitchhiked the rest of the way back to school. This time, when I got back, the school officials as well as the police were waiting for me, and they demanded to know where I'd been. I refused to tell them. There were two or three policemen trying to intimidate me. I dug in my heels and didn't say anything. I knew that if I told them where I'd been or that I had been with Rinpoche or anything like that, it would destroy my chances of ever seeing him again. Finally, they told me, "All right, but if you ever leave school again without permission, you'll be expelled and put into juvenile detention."

At school they were now aware that I was in real trouble. I had reached a point where I was not functioning, not doing anything. The housemistress was very sweet and not judgmental at all. She tried to be helpful. She knew that I was in a difficult family situation, my father having died and my mother being so unstable at this point.

During this time, I went home for a few days. I had an appointment with our family physician, and I told him that I was sexually active. He immediately wanted to give me contraception. He told me that my mother was having a nervous crisis and that if I became pregnant, it would finish her off. My mother had many psychological problems even before my father died. The biggest problem for me was that she wanted me to be a particular way, and what I did was never good enough for her. During this period, she ignored the fact that I was in psychological distress myself and just kept saying, "Oh why can't you be like so and so?" She wanted me to be, not even who she was, but who she had always wanted to be.

She was trying to advance me socially, to have me marry the right man and do the right things and have the right sort of feminine attitude and all of that. She didn't seem to appreciate how unhappy and miserable and confused I was. All I wanted to do was to be with Rinpoche and I couldn't relate to anything else.

My mother did send me to a psychiatrist in London during this period. He opened our session by saying, "Your mother tells me that you want to be a dropout from society." I replied eagerly, "Yes, I do!" So he said, "Oh, do tell me about it:' He was so enthusiastic that I felt that he was about ready to drop out himself. We talked about Buddhism and other things, and finally he said to me, "You know something, I have to confide in you. Your mother is a very troubled person. She has alienated a lot of people around her, including you. I actually think you're doing quite fine." For a short time, this made me feel a bit better about myself.

Throughout the term at Kirby Lodge, I continued to be out of touch with the academic situation. I maintained a vegetarian diet at school, eating the rather disgusting English boarding school food, but not meat or eggs. I became somewhat disconnected from the world around me. The more I thought about it, the more I felt that I couldn't continue to live with my mother. My sister had already moved out, and the spectacle of being alone in London with Mother over the upcoming Christmas holiday was unbearable. I talked to my housemistress about this, and she seemed very understanding. We talked about alternatives, and we came up with the idea that I could stay with my aunt and uncle in Northumberland. I asked to be put in their custody. I thought that was a good option. They seemed to be fairly stable people, and I felt that I'd be in a more neutral situation with them.

Shortly thereafter I got a telephone call from my mother. The housemistress had obviously phoned her. Mother was furious and told me, "I can't believe you've done this. I'm expecting you home for the Christmas holidays, and I've already bought flowers for the house. I can't believe you're thinking of not coming back." That was the depth of our communication at that point. I felt that I had no choice but to give in to her, so I ended up going home for Christmas. I had a shrine in my bedroom there, with a picture of Rinpoche, a statue of the Buddha, and some butter lamps on it. My sister had painted my room in bright Tibetan colors: orange and maroon and deep blue, which I loved. While I was away at school, my mother had my bedroom redecorated. She repainted, did away with my shrine, and put up curtains with a Chinese design on them. She said to me, "Well, you should like this. It has an Asian theme." It was just Mother and me for Christmas. Did we celebrate? I don't even remember.

Right after Christmas, Rinpoche called me in London, pleading with me to come up to Scotland for the New Year. I didn't know how to persuade my mother to let me go, but then I hatched a plan. I called some friends who were also students of Rinpoche's, Stash and Amalie, who lived near Eskdalemuir, and told them that I needed a cover so that I could see Rinpoche. Stash knew how to do the English upper-crust thing really well, so he called my mother and said that he and his wife were having a lovely New Year's Eve party at their home in Scotland. He told my mother, "I'd really like Diana to come for it. But please be very careful about train tickets, because of all the drunken people on the train this time of year. I think you'll have to spend the money on a first-class ticket, and we'll pick her up at the station in Carlisle." My mother was quite charmed, so this time I ended up having my way paid first class to Carlisle.

I had an instinct that I would never be coming back. When I was packing, my mother walked into the bedroom and said, "You're taking so many things. You're packing as if you're leaving home." I laughed and said, "Oh well, I just don't know what I'm going to need to wear."

When I got off the train, I got a taxi directly to Garwald House and met Rinpoche there. I never even saw Stash and Amalie that night. I arrived on December 30. The next night, New Year's Eve, was wild. Rinpoche and I drove around with some friends to visit various people. The first place we stopped, the people had put hashish in their Christmas cake. After they'd eaten it, they'd had a terrible fight and had broken every piece of china in the house. We went on from there to visit Stash and Amalie, who lived in a cottage in a remote area. We continued making the rounds at Eskdalemuir, stopping at a number of friends' houses.

Halfway through the evening, we joined up with the Woodmans, who owned the house where Rinpoche was living. After that, I remember encountering a lot of negativity toward Rinpoche, and some that was directed at the two of us. I don't know exactly what had happened, whether Rinpoche had gone one step too far for them at that point, or if there was jealousy because of me, or what. However, the situation felt hostile and rather weird.

For Rinpoche at that time, there was so much personal crisis and personal growth taking place simultaneously. He was quite young, if you think about it, just twenty-eight, and he was dealing with incredible forces of change in his life. He'd lost his own culture in a horribly brutal way and had been exiled to a strange land. Then he'd had the big message of his car accident and the subsequent paralysis, which was a major turning point for him spiritually. He used to say to me that there was a point in your spiritual development where you could either go crazy or become enlightened. He was right there, on that point.

I think that he felt abandoned to a large extent, misunderstood both by the Tibetans and by his students. Most of the English students, even those who had been quite close to him, couldn't go along with him at this point. He just didn't fit the mold of a spiritual teacher that the English people wanted. They found him brilliant, but they were also intimidated by him. They could venerate an Asian guru if he remained a holy little man, but a powerful figure like Rinpoche was threatening.

So when I came into his life, there weren't very many people there for him. At the same time, although this era was terribly bleak, he was giving birth to something much more powerful than what had happened in the past. It was a very pregnant time. In October of 1969, Rinpoche had sent a letter to the lawyer for Samye Ling, who was also one of his students, in which he talked frankly about the whole situation. Early in the letter he talks about his decision to disrobe:

I have decided to give up the robe, which I feel stood as a subtle obstacle to the formulation of my teaching in the West. The monk's robe confused many here as a glorious image of spirituality. However, my teaching concerns actual experience. I don't feel that I need to hide behind something, though some people are critical of me for coming out and showing myself as a human being.1

He continues,

To be quite frank with you, I feel that I must make it quite clear that the disapproval which has been directed toward me from some so-called Buddhists, including some of my compatriots, has been a fear of plunging in in this way. My very existence becomes an enormous threat to them because I am utterly without fear in this world of violent change.2

That New Year's Eve, after we went round and visited Rinpoche's students in Eskdalemuir, we went back to Garwald House. Rinpoche got on the phone, and at first I thought he was calling people to wish them a happy New Year. I finally realized that he was calling his old girlfriends and inviting them up to the house. Four or five young women arrived within the hour, and they were each put up in a different bedroom for the night, while I slept with Rinpoche in his room. When I asked him what on earth he was doing, he said, "I'm trying to decide which of you I'm going to marry." Somehow I knew that it would be me, so I didn't feel threatened, as strange as that might sound. But what a bizarre spectacle!

In the morning when I woke up, I wanted to go down to the kitchen to get something to eat, but I couldn't find my nightgown or a robe to put on, so I grabbed Rinpoche's Tibetan robe, his chuba, wrapped it around myself, and went downstairs. Pamela Woodman was there, and when she saw me, she started screaming at me, "Who do you think you are? Who do you think you are that you can wear his chuba?" There was tremendous black negativity in the air.

Later that day, after saying goodbye to all the assembled ladies, Rinpoche and I decided to escape the whole scene at Garwald House and go to Edinburgh. 1 thought that we might be getting married there. Rinpoche just said, "Let's get out of here," and I agreed. I phoned my sister, and she and her boyfriend Roderick arrived at Garwald House to drive us. We packed a few things, got in their car, and headed north. We stopped in Glasgow for the night. We didn't have much money, so we stayed in a tiny, disgusting little place where every hour or two the heater would go off and you had to spend a half-crown to get it to come back on. Rinpoche and I would fall asleep, only to be woken up when it was freezing in the room. Then we'd have to find another half-crown and put it in the heater. We spent the whole night like that. The next night we moved into a nicer hotel in Edinburgh.

The period from Rinpoche's accident until we married and left for America a year later was one of the darkest times in his life. Rinpoche was often in the depths of depression. He was sick with pleurisy and pneumonia, he was crippled, his Tibetan compatriots were trying to control him, and many of his students had left him. He felt that his only reason for existence was to present the Buddhist teachings. Akong refused to support him in teaching the way that he wanted to, and he had very few students in England who could hear what he had to say. For Rinpoche, if he had no opportunity to present the buddhadharma, the Buddhist teachings, life was not worth living. He told me at several points that if he couldn't teach, he had no reason to go on.

That night in the hotel, Rinpoche had a big jar of Seconals, which are sleeping pills. I don't know where he had obtained them. At one point that night, he turned to me and said, "Let's take all these pills. Let's just do it." I grabbed the bottle out of his hand and threw the pills out of the hotel window, saying, "We're not going to do that. There's a future for us." Then we went to bed.

I'm not sure if Rinpoche really meant it, if he actually would have taken an overdose. One might think he was testing me somehow, but I'm not so sure. If! had said, "Okay, yes, let's kill ourselves," I think he might have gone ahead. He loved those Japanese movies where the star-crossed lovers commit double suicide, a bit like Romeo and Juliet.

I'm sure it's difficult to understand how a spiritual teacher could even contemplate taking his own life. But Rinpoche was just so real. He wasn't like anybody's concept of a spiritual teacher. Of course, I found the suggestion that we take all those pills quite shocking, although I felt tremendous sympathy for what Rinpoche was going through. In a way, it seemed like a very human response to his situation. Thank heavens I kept my faith in our ability to transcend this awful situation. I don't mean to suggest that I saved his life, exactly. It was more that I was part of the circumstances or the atmosphere that gave him a future. I don't know if you can understand this, but there were many times in my husband's life when circumstances intervened and helped him. I felt as though I were part of that support system -- which almost felt like a cosmic coincidence of some kind.

Later, I heard about another great Tibetan teacher who was driven to the brink of self-destruction. In the eleventh century in Tibet, there was a famous meditator named Milarepa, who is probably the greatest saint. in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. He spent years trying to receive the highest teachings from his guru. Because of Milarepa's particularly stubborn and difficult nature and because of his many misdeeds in the past, his teacher made him undergo many tests and trials. Nothing seemed to please his guru. Finally, Milarepa became so discouraged and convinced that he would never receive the final spiritual empowerment that he decided he would take his own life. His teacher appeared just as he was about to hurl himself over a cliff. At that point, feeling that Milarepa had finally surrendered completely, his guru gave him the ultimate transmission. My husband always said that he admired Milarepa because everything he did was undertaken with an attitude of complete warriorship. My husband lived his life in the same way. He was an extreme human being, and he lived his life with extreme and immaculate concern for others. When he became depressed and suicidal, it was not out of self-pity.

The next morning, January 3, 1970, we decided that we were going to get married. What an outrageous time to make this decision! Most people, looking back on their courtship and marriage, would see a happy picture, I think. Our bond, obviously, was not forged out of any such cheerful circumstances. What we had, however, was a true connection, and I never doubted my love for Rinpoche or his genuine love for me.

On January 1, a law had gone into effect in Scotland that made it legal to get married at sixteen years of age without your parents' consent. The morning of the third, Rinpoche called Akong and Sherab Palden at Samye Ling and told them that we were getting married. They came up to Edinburgh right away, but it was like they'd come for a funeral. That's the only way I can describe it. Our marriage was a huge mistake as far as Rinpoche's Tibetan colleagues were concerned, further proof that he was not going to remain securely within the fold. Akong was sullen and wouldn't look me in the eye. I think the icing on the cake for him, so to speak, was that Rinpoche was going to marry a white girl. At that point, Akong might have given in and softened to the situation, but instead he seemed to become more rigid. In doing so, he sealed shut a door of intimacy that had been open between Rinpoche and him, not just in this life, but for many lifetimes. In the letter I quoted from earlier, Rinpoche also addressed his relationship with Akong:

There is much that I think you ought to know about the situation at Samye Ling .... Most of the difficulty boils down to a basic disagreement between Akong and myself. I have not acted more forcefully as of yet because I feel that he is involved in a deep personal crisis through which I want him to discover his own way himself. At heart the problem is that same lack of courage and lack of faith which I have tried to impress on you as the ultimate danger ....

The point is that Akong wishes to control me and use me in a very limited way. He feels that my "becoming Western" is a "disgrace to Tibet" -- (pride lies very near the surface here). But my role is a far deeper one than a mere cultural mission, a representative of the East in the West. I am not Tibetan but Human and my mission is to teach others as effectively as I can in the world in which I find myself. Therefore, I refuse to be bound by any "national" considerations whatsoever. And if Akong wishes to work effectively now, he too must have the courage to break through his Tibetanness, to stop hiding behind our national background .... 3

I think that Akong was hoping that at the last minute Trungpa Rinpoche would change his mind about marrying me, but that didn't happen. Akong and Sherab went with Rinpoche and me to a very formal old Scottish building to apply for our marriage licenses. Rinpoche and I must have been quite a sight as we approached the registrar: a rather short, crippled Tibetan man, age twenty-nine, wearing a special caliper on his leg and a cumbersome walker to support him, and a tall, sixteen-year- old English girl with long blonde hair. The registrar had a Bible, and he said to Rinpoche, "Put your hand on this Bible and swear before God." And Rinpoche said, "I'm sorry, I can't do that. I'm a Buddhist." That was all right for him, but then the registrar gave me the same instruction, and I said, "I'm also sorry I can't do this. I'm a Buddhist." This absolutely appalled him. Here I was, a young English girl who had obviously run away from home and a good family, and on top of that I had renounced Christianity. I thought for a moment that he might not give us the marriage licenses, but he did.

After we got the license, we had to go to the justice of the peace to perform the actual wedding. Before the ceremony, Akong and Sherab bowed out and went back to Samye Ling. Rinpoche had taken me shopping earlier in the day and had bought me a beige camel-hair suit, so at least I didn't get married in one of my hippie caftans. I think he was trying to clean up my act a little. He wore a dark gray flannel suit and tie. Before we got married, we got our picture taken in one of those booths where you put in a coin and take four pictures really quickly.

My sister, her boyfriend, and a couple of other friends went with us to a little hall where we were married by a justice of the peace. We took our vows sitting on folding chairs. We said all the traditional things: we promised to honor, obey, and love one another. I got two gifts: a muslin shirt and a bunch of daffodils. Later, Rinpoche said that we should get married again and have a proper wedding, but we never did.

When we came out of the hall after the ceremony, there was a scene with the press. Because of the new law, a number of reporters were hanging around to see who was getting married, and as we left the hall, they took photographs and tried to interview us. After we escaped the reporters, we went out to eat with our friends and then went back to the hotel and got in bed.

Shortly thereafter, our hotel room door burst open and more reporters came into the bedroom. They said to me, "We want to get some information. You've married your gobo. We need information. Tell us all about it." They didn't know what a guru was, so they kept calling Rinpoche my" gobo," a meaningless word. We were both horrified. That was one of the few times in those early days that I saw Rinpoche become really angry. He yelled at them, "Get out of here before I smash your cameras." And they left.

There were other ,dramas that evening. The press went to my mother's house in London and said that they wanted to ask her some questions about the daughter who'd just married a Tibetan guru -- or gobo. My mother went into shock and said, "Oh my God, oh my God, Tessa got married. I can't believe it." Then they told her, "No, no, it's not Tessa, it's Diana." My mother fainted.

Rinpoche and I received a telephone call later that night from a friend of my mother's, saying that my mother was having the marriage annulled because I was underage. Rinpoche kept telling me not to worry, that it was okay, and that she wouldn't be able to do that because the marriage was legal and we had the marriage license to prove it. But it was still frightening.

The next morning we got the newspapers and discovered that our marriage had made the front page of the People and the Express, as well as the back page of the Sunday Mirror, none of which are among the better English papers. The Sunday Mirror featured a picture of Rinpoche and me, with the caption "Diana, 16, Runs Away to Marry a Monk." Seeing our picture in the tabloids must have been terribly humiliating for my mother.

However, for me, the most outrageous event occurred after all the reporters had gone away and the phone calls had ended. Late that morning, while we were lying in bed, Rinpoche decided he would call some friends to announce our marriage. His first call was to a friend in Wales, and I remember him saying, "Mary, a very exciting thing has happened to me. I'm married." And then he said, "Yes, yes, she's sixteen years old." Then I could hear her talking on the other end of the line, but I couldn't) hear what she was saying. Rinpoche looked slightly quizzical, there was a pause, and then he said, "Hold on a minute." He put his hand over the mouthpiece of the telephone, and he turned to me and said, "Excuse me, Sweetheart, but what's your name?"

He had actually forgotten my name! Rinpoche lived his life without the conventional reference points that most of us cling to as the anchors of our sanity. I don't know if you can possibly imagine what I felt at this moment. It wasn't that I felt he didn't care about me or that fundamentally he didn't know who I was. In fact, he knew me better than anyone else dig. But on the morning after our wedding, he couldn't remember my name. Not at all. Not Diana, not Pybus, not any of it. So I told him my name, and he happily went back to his phone conversation as though nothing had happened.

I, meanwhile, was freaking out. There was no regret on my part, but I realized that I had gotten myself into the wildest situation possible. I lay in bed thinking, "I don't know what's going to happen in my life.You know, I really at this point do not know at all what lies in my future. But I do know one thing: my life will never be boring. It definitely is going to be amazing and unusual." On the whole, I was both excited and terrified at the prospect of spending my life with such a person.

That was how our marriage began. I don't really blame my parents for the unusual path I've taken. They had something to do with it, but it is also the result of who I am. I chose this marriage and this life. As I said before, until I met Rinpoche, I never could connect with the world as a whole. I always felt different. I never felt like I was one of "them" at all. Meeting Rinpoche and being in his world were the first real things that happened for me in my life.

Once I entered his world, I didn't have any objective reference points, nothing to fall back on and say, "Well, this is normal, this is civilized. This isn't." For me, there was absolutely no other reference point. Just him. Just us. Just our marriage. I spent a lot of years married to Rinpoche operating in that space with him.

Later, when I started my intensive dressage training, I knew that I had to acknowledge the conventional world and some sort of conventional wisdom and behavior if I was going to find a place for myself in the riding world. I tried to keep those two worlds, my marriage and my career, separate so that I would be accepted in the riding world. Rinpoche's world was not a problem for me. It was just a bit of a balancing act.