Venerable Kapilavaddho and the English Sangha Trust

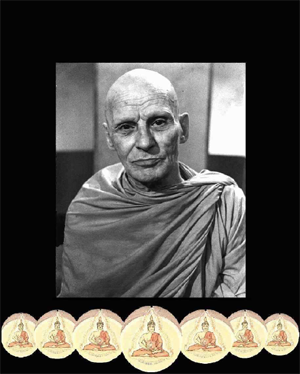

1955-1957We pay tribute to a man who founded the English Sangha Trust and who, after an absence of ten years, returned to lead it from the dolorous state into which it had fallen. He had in the course of his lifetime several different names, as will appear but it is fitting to head this tribute with the name and designation that he twice bore with wisdom, courage and dignity. There will be many, to whom the earlier parts of the almost incredible saga of this man are unknown, and it is with such people in mind that the story is told at some length.

William August Purfurst was born at Hanwell, Middlesex, on 2nd June 1906.

William August Eugene Purfurst, 1906-1971

William August Eugene Purfurst was born ... to William August Eugene Purfurst and Margaret Holland Purfurst (born Woods).

Margaret Holland Woods, 1886-1957

Birth: June 1886, Hanwell, Middlesex, England, United Kingdom

Death : 9 April 1957, Westminster, London, England, United Kingdom

-- Margaret Holland Woods, by ancestors.familysearch.org

William was born on July 20 1880, in Kensington, Middlesex, England, United Kingdom.

Margaret was born in June 1886, in Hanwell, Middlesex, England, United Kingdom.

William had one sister: Margaret Elizabeth Mary Purfurst.

-- William Purfurst, by myheritage.com

As the name indicates, his father was of German origin, and he was an only child. His father died when he was quite small, and he was brought up under the care of his mother, to whom he remained devotedly attached until her death in 1957. Young William soon showed himself to be a man of many and brilliant gifts. There is no doubt that he could have made a career for himself either in business or in the academic world. He had a remarkable gift for acquiring a wide variety of experiences and — what is more — profiting from them. At the age of 20 he was living in Bristol as manager of a branch of an internationally know typewriter firm, but the world of business could not satisfy him. He started studying such things as psychology and philosophy, eagerly seeking to find answers to life’s riddle. But his compulsively inquiring mind was not so easily satisfied with the “solutions” proffered by the books he read. Perhaps already at this time he began to suspect that the scholars and philosophers of the West had no monopoly of wisdom. In any case, he felt that the only place for him to pursue his studies further was London. After two years, he gave up his Bristol job and set out for the capital where he had been born, on foot: an action, which was symbolic of his future career. From then on, he stood on his own two feet, and if necessary walked on them to wherever he felt he had to go.

An expert photographer, he soon got himself a job in Fleet Street. He returned each night from the day’s work to his private studies, his private questing. He was ever trying to find out the nature of things, the reason for man’s existence, and was not going to be fobbed off with any easy answers. But as happens, the deeper he probed the further off the solution to his questions appeared.

At the same time, the first of his teachers appeared on the scene. This man, perceiving qualities that resided in the young Purfurst, took him under his wing, giving him an intensive course in the philosophy of the East. Starting with the Vedas and the Upanishads, Yoga and Vedanta — all as a preliminary to the real kernel of the course, which was Buddhism. Discipline under his teacher was strict — he had to work each evening at his studies, and also undertake a regime of strict physical training. He stuck it out, mastered the philosophical course and at the same time gained considerable control over his own body and emotions. All this had been undertaken in his spare time, in the evenings after his journalistic work.When his friend and mentor died, he continued on his own, extending his studies into other fields such as anatomy and chemistry. As a result of these studies, he was able to develop a new colour printing process which in one form or another, is still in use today.

This was his life until the outbreak of war in 1939, when he became an official war photographer. However as a man of action, he found life dull in the early days of the war. Nothing seemed to happen, so he trained as a fireman. By the time his training was completed, the picture had changed. The blitz had begun. As an officer of the National Fire Service in London he soon found all the “action” he could ask for, and more.

He had some hair-raising experiences amid burning, crashing buildings, while bombs rained down and the ack-ack guns opened up, amid burst mains and sewers. Crawling among precarious ruins, digging out the living and the dead, going without sleep, food, drink, or even his precious cigarettes, and of course constantly risking his own life for the sake of others. In his case, though he distinguished himself by his fearlessness, such a life was after all not so very exceptional. He was a Londoner born and bred. Although they had not yet met, there was another man in London doing very similar things, whom one would scarcely have expected to meet in such a situation. This was a Burmese bhikkhu, the Venerable U Thittila, who had come to work in London at scholarly pursuits when war overtook him. He was equal to the occasion and, boldly doffing the robe, he joined the ambulance service and worked in blitzed London under similar conditions to William Purfurst. This experience gave Venerable U Thittila a unique insight into the British character. And it probably also did much to forge the bond of friendship, which eventually grew between the two men.

As D-Day approached, William Purfurst’s wartime activities changed in character. He became a civilian photographer attached to the Royal Air Force, his job being to take pictures of army parachutists who were dropped on enemy territory. In order to equip himself for this task, he himself volunteered for a parachute course took the full training and did a number of drops. He then went as a photographer on a number of missions until the war in Europe finally ended.

Towards the end of the war he also got married, and having left the service he became a WEA (Workers Educational Association) lecturer in philosophy, in which capacity he travelled a great deal up and down the country.It was about this time that he met Venerable U Thittila, whose pupil he promptly became. The bhikkhu who had been supported by the Buddhist Society resumed the robe somewhat informally (he had to be re-ordained, later, in Burma) and gave many lectures and classes at the Society’s old premises in Great Russell Street, where William Purfurst was also active as a speaker.The Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland

Table of Contents of The Buddhist Review, July, August, September, 1911

Frontispiece: The Central Portion of the Temple of Angkor Wat.

The Great Temple of Angkor Wat. By M. George Coedes.

Knowledge and Ignorance. By Dr. Edmund J. Mills, F.R.S.

The Ballad of the Lamp. By Pathiko.

Buddhism and Theism. By Sakyo Kanda.

Buddha Day Celebration in London.

The Daily Duties of a Buddhist. By the Anagarika H. Dharmapala.

The Passing of a Great Man.

Third Annual Meeting and Balance Sheet of the Society.

New Books and New Editions.

Notes and News.

The Society has for its objects the extension of the knowledge of the tenets of Buddhism, and the promotion of the study of Pali, a language allied to Sanskrit, in which the original Buddhist Scriptures are written.

The Society publishes quarterly The Buddhist Review, and issues works on Buddhism, which are on sale to the general public at 46 Great Russell Street, London, W.C.Membership of the Society does not imply that the holder is a Buddhist, but that he or she is interested in some branch of the Society's work.

The Annual Subscription is One Guinea (Members), or Ten Shillings and Six-pence (Associates), payable in advance at any date. Donations will be gratefully accepted.

Meetings are now being held each Sunday at 7 p.m. at the rooms of the Bacon Society, 11, Hart Street, Bloomsbury, London, W.C. Friends are invited to take part in these meetings, which are open to all, and to help by delivering lectures or sending papers to be read. Contributors should, if possible, submit their papers to the Lecture Secretary at least one week in advance.

-- The Open Court, A Monthly Magazine, Volume XXV,

Open Court Publishing, 1911

Purfurst’s activities were by no means confined to London. There were eleven people in Manchester who had been studying the Buddha Dhamma under him, for nearly a year. They had formed themselves into a group called the Phoenix Society; and each weekend he travelled from London to conduct an exhaustive program of theory and practice. Others came and the group grew, within months it became the Buddhist Society of Manchester. It was the first active society outside London. Almost at the same time the teacher had taken his own first steps towards becoming a Buddhist monk. The urge to proceed along the Buddhist path is the only way open to a man of his temperament, namely the total devotion to and immersion in the Dhamma implied by the bhikkhu life. It was so strong that eventually an understanding wife gave him the freedom to answer this call. It was indeed she who urged this step on him. Thus they parted, and shortly before Wesak in 1952 William Purfurst adopted the status of a homeless one, an anagārika. Following this he took the Pabbajjā or novice ordination to become Sāmaṇera Dhammānanda, which he did under the Venerable U Thittila on Wesak 1952.

Venerable U Thittila remained his mentor until himself returning to Burma to take up a university post in Rangoon.

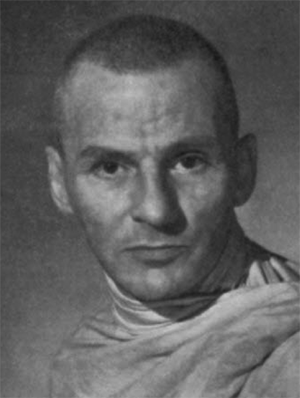

Now the name of William Purfurst disappears, and instead there is the Sāmaṇera Dhammānanda working for the Buddhist Society, lecturing and conducting classes, travelling up and down the country in his three cotton robes, inspiring and founding Buddhist Societies at Oxford and Cambridge. During this time the Buddhist Summer School, later taken over by the Buddhist Society, was founded, and continues to this day as an increasingly popular annual event. The sheer physical hardship of his existence at this time should not be under-rated. At one time, in fact, he even “went missing” for a fortnight, virtually starving and sleeping on park benches in his scanty attire, till he almost succumbed to exhaustion and fever. But this was merely typical of the man. He conducted experiments on his own body and mind in much the same spirit as the late Prof. J. B. S. Haldiane had done in the name of science. Nor was he unmindful of the six years of austerity and self-torment, endured by Gautama in the days of his Noble Quest (Ariyapariyesanā, cf. Middle Length Sayings, No. 26), which preceded his enlightenment. Even his sternest critics and it is only truthful to admit that he had many at times, were bound to concede that he had the sheer guts to do many things that most of them would never have attempted.

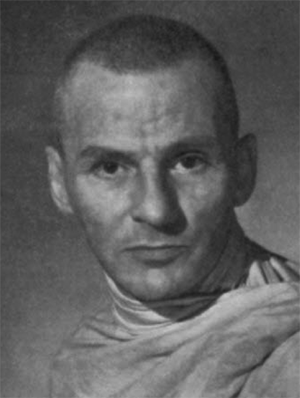

The Sāmaṇera Dhammānanda

The Sāmaṇera DhammānandaHis uncompromising adherence to the precepts and rules of the Sangha, and his determination to prove that the bhikkhu life was liveable in the West, eventually drew respect and support, not just for him as a man, but for the Buddha Dhamma. For his way of life gave new meaning and confidence to many people to whom Buddhism had merely been a remote eastern religion. The new “Apostle” of Buddhism attracted a good deal of attention, not all of it uniformly favourable or kindly, from press, radio and TV.

Incidentally, the sāmaṇera’s wanderings up and down the country entailed a certain amount of organising to enable him to keep the rules strictly — and those included not handling money. Thus when he travelled by train to, say, Manchester, he was escorted to the station where a return ticket was bought for him, met at the other end and taken to the meeting-place by car, and so on. On the other hand, his pupils or listeners did not have to bother about an evening meal for him: all that had to be provided (where he was not staying the night) was a cup or two of tea. His one indulgence, permitted by the rules, was smoking, and a packet of cigarettes was always gratefully received. There were some who criticised him for this, which they might have been entitled to do had they been willing to put up with the other austerities and inconveniences of his life. As a matter of fact, bhikkhus in the East frequently smoke, and if they don’t, they probably chew betel nut instead.

However, it was not possible in the long run to proceed further on his chosen course without going East. It was not only impossible for him to obtain the higher ordination as a bhikkhu in the West — it was also clearly imperative to go to an Eastern monastery for a spell of intensive training before he would be fully equipped to live and teach the Dhamma in Britain. This posed a serious problem of finance. In fact the only way out at that time was to revert to lay life, get a job and earn some money. The Sāmaṇera Dhammānanda therefore once again became William Purfurst. The job he got was that of barman in a Surrey hotel. He was completely careless of the criticism which this action of his aroused in some quarters. It was neither the first nor the last occasion that wagging tongues were set in motion against him. He was no more deterred by these things than by the physical obstacles he had encountered in the past. As usual, he just went straight ahead.

His teacher being Burmese, Burma was the place he might have made for, but difficulties presented themselves here and he could not get a visa. In the end it was Thailand to which he went. In October 1953, Phra Ṭhittavadho arrived in England from Bangkok and it was through his intervention that a visa was obtained. Money for the journey was raised in England, and in March (February according to Life as a Siamese monk) 1954, William Purfurst travelled to Bangkok. The Lord Abbot, the Venerable Chao Khun Bhāvanākosol, accepted him at Wat Paknam, Bhasicharoen, Dhonburi. His Lower ordination took place on 19th April, and on 17th, May 1954 at Wesak, he at last became a fully ordained bhikkhu with the name of Kapilavaḍḍho (“he who spreads the Dhamma,” but at the same time with a reference to Kapilavatthu, the Buddha’s birthplace).

Here he submitted to a severe course of training as a vipassanā bhikkhu. He also passed examinations in Vinaya, Sutta and Abhidhamma, thereby qualifying as a teacher in both theory and practice. Under this great teacher at Wat Paknam he gradually became renowned as a highly skilled meditator and as a scholar in the Dhamma. He lectured throughout the length and breadth of Thailand to vast crowds, and with an ever growing reputation for his qualities as a teacher and for his rigid observance of the traditional bhikkhu life. As a result, he was given permission by the Lord Abbot to return to Britain with full authority to give instruction in meditation as well as the theory of Buddhism.

He became the first European to be ordained a Bhikkhu in Thailand The long wait…The Sāmaṇera having answered all the questions and paid salutations taken the ten precepts. Having received instructions on the holy life and possessing the eight allowances he waits in meditation for the call of the Upacāriya, the call famous throughout two thousand four hundred and ninety eight years, “come bhikkhu.” On this call he will go into the body of the Saṅgha.

The long wait…The Sāmaṇera having answered all the questions and paid salutations taken the ten precepts. Having received instructions on the holy life and possessing the eight allowances he waits in meditation for the call of the Upacāriya, the call famous throughout two thousand four hundred and ninety eight years, “come bhikkhu.” On this call he will go into the body of the Saṅgha.During this period he was interviewed by Robert Samek, Lecturer in Commercial Law in the University of Melbourne, and the text of this interview was later published as An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy.

The procession, led by Upāsikās (female disciples keeping eight precepts) followed by many happy lay followers, set off on the walk three times around the pagoda. The Sāmaṇera coming for final ordination follows behind, being attended by supporters and walking under the protection of ceremonial sunshades.

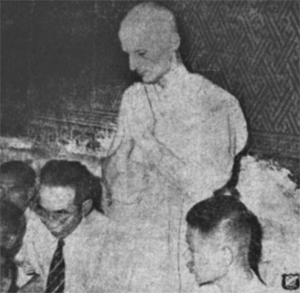

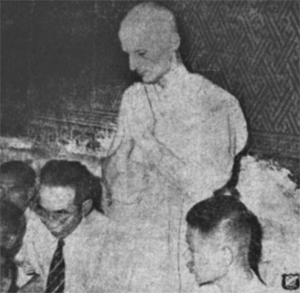

The procession, led by Upāsikās (female disciples keeping eight precepts) followed by many happy lay followers, set off on the walk three times around the pagoda. The Sāmaṇera coming for final ordination follows behind, being attended by supporters and walking under the protection of ceremonial sunshades.On 12th November 1954, the new bhikkhu returned to England. His return was given considerable press coverage. Meantime, on initiative from Ceylon, Venerable Nārada Mahāthera had opened the London Buddhist Vihāra at Ovington Gardens Knightsbridge on 17th May 1954 (since moved to Chiswick). It was here that he took up residence, after a brief stay in Manchester. A picture of the Prime Minister of Ceylon, on a visit to London, prostrating himself before the English bhikkhu, attracted much attention and even appeared in the Italian press.

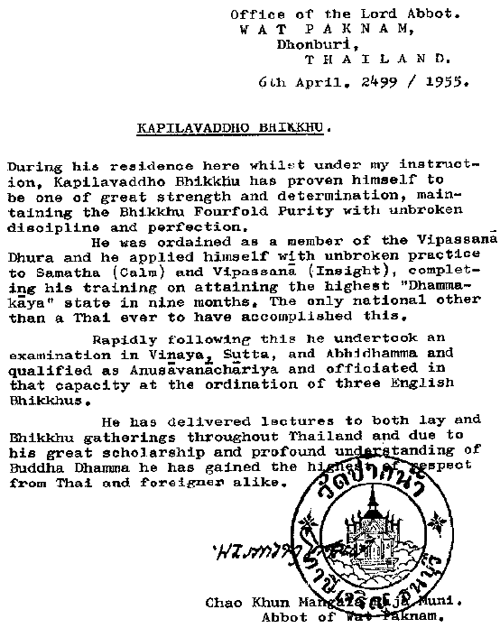

Office of the Lord Abbot.

Office of the Lord Abbot.

WAT PAKNAM,

Dhonburi,

THAILAND.

6th April. 2499 / 1955.

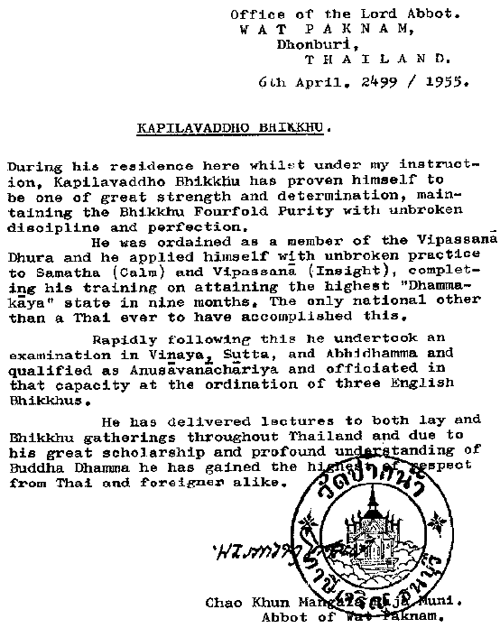

KAPILAVADDHO BHIKKHU.

During his residence here whilst under my instruction, Kapilavaddho Bhikkhu has proven himself to be one of great strength and determination, maintaining the Bhikkhu Fourfold Purity with unbroken discipline and perfection.

He was ordained as a member of the Vipassana Dhura and he applied himself with unbroken practice to Samatha (Calm) and Vipassana (Insight), completing his training on attaining the highest "Dhammakaya" state in nine months. The only national other than a Thai ever to have accomplished this.

Rapidly following this he undertook an examination in Vinaya, Sutta, and Abhidhamma and qualified as Anusavanachariya and officiated in that capacity at the ordination of three English Bhikkus.

He has delivered lectures to both lay and Bhikkhu gatherings throughout Thailand and due to his great scholarship and profound understanding of Buddha Dhamma he has gained the higest of respect from Thai and foreigner alike.

Chao Khun Manga___ Muni.

Abbot of Wat Paknam.

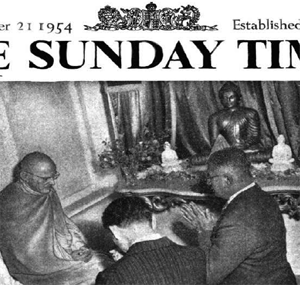

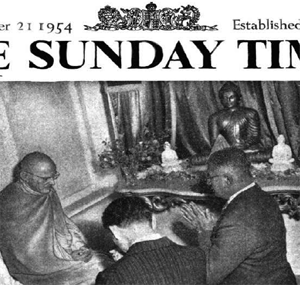

Source: Alan James, (Aukana Trust) Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho scrapbook"Sunday Times"

21st November 1954

The Prime Minister of Ceylon, Sir John Kotelawala, now on a visit to London, went yesterday to Knightsbridge to Britons only Buddhist Temple to pray at the shrine of Buddha, on which he laid a bowl of chrysanthemums. The saffron-robed monk before whom he kneels is an Englishman, Mr W. A. Purfurst, known as Bhikkhu Kapilavaddho.

The Prime Minister of Ceylon, Sir John Kotelawala, now on a visit to London, went yesterday to Knightsbridge to Britons only Buddhist Temple to pray at the shrine of Buddha, on which he laid a bowl of chrysanthemums. The saffron-robed monk before whom he kneels is an Englishman, Mr W. A. Purfurst, known as Bhikkhu Kapilavaddho.

Source: Alan James, (Aukana Trust) Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho scrapbookThe Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho’s mode of practice at this time was called the “Wat Paknam” method or Vijjā Dhammakāya meditation (also called Solasakāya) (see warning page p43 ED).

“The technique leads the meditator directly along the path to enlightenment and emancipation by combining concentration (samatha) and insight (vipassanā) meditation techniques. It is thus extremely focused and effective. The technique begins by concentrating on a point inside the body in the centre of the abdomen, two finger-widths above the navel. This point is said to be the place where consciousness has its seat. The words “Sammā Arahaṃ” can be repeated mentally to aid initial development of concentration. A luminous nucleus appears at the centre point, and then develops into a still and translucent sphere about 2 cm in diameter. Within the sphere appears another nucleus, which emerges into a sphere. The process continues with increasingly refined spheres or forms appearing in succession. The high levels of concentration achieved are used in vipassanā to develop penetrating insight. A qualified teacher is important in this practice. The late abbot Venerable Chao Khun Mongkol- Thepmuni (1884-1959) popularised this meditation system. The Wat has a book in English, “Sammā Samādhi” by T. Magness, which explains the technique in detail” (Wat Paknam website). Cyril Bartlett composed a 16 body picture for this purpose (EST library).

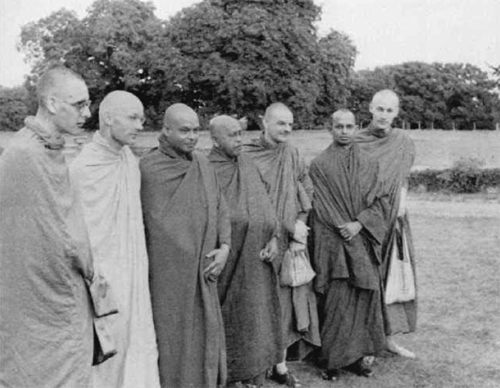

Hodderston Summer School 1955

Hodderston Summer School 1955

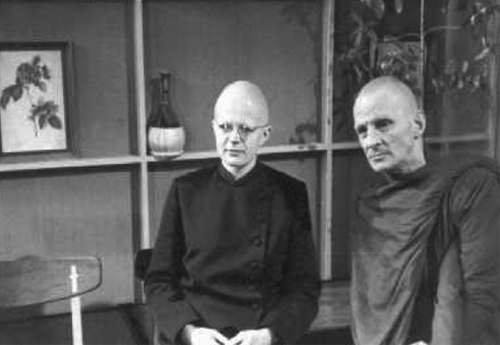

1. Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho

2. Sāmaṇera Saddhāvaḍḍho

3. Maurice Walshe:- Vice Chairman of the Buddhist Society 1957; Chairman of the English Sangha Trust 1962

4. Mr Maung maung Ji

Source: Ajahn Paññāvaḍḍho, Abbot of the English Sangha Trust 1957-61A principal reason for his return was the establishment of an English branch of the bhikkhu Sangha. This became a possibility once three young men (one English, one Welsh and one West Indian) joined him. The first step was taken when, on 5th July 1955 the first of three lower ordinations took place at Ovington gardens. Those ordained were Robert Albison, George Blake and Peter Morgan. They became the Sāmaṇeras Saddhāvaḍḍho, Vijjāvaḍḍho and Paññāvaḍḍho (He who spreads Faith, Knowledge, and Wisdom respectively), the officiating bhikkhus being Venerable Gunasiri Mahāthera the incumbent, and the Venerable Mahānāma Mahāthera, both from Ceylon, besides of course the Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho himself. The bhikkhu and the first named of these sāmaṇeras made a noteworthy, and much publicised, appearance at the Summer School at Hodderston in August 1955.

1. Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho

1. Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho

2. Sāmaṇera Saddhāvaḍḍho (Robert Albison)

3. Mr Bartlett (EST Chairman)

4. Peter Morgan (To become Venerable Paññāvaḍḍho)

5. Mrs Bartlett

6. Mr Mynssen (EST Director)

7. Mr Bradbury (EST Director)

8. Mrs Bradbury

9. Miss Markuse (Latvian Upasika)

Source: Ajahn Paññāvaḍḍho, Abbot of the English Sangha Trust 1957-61The need for more organisation and funds to promote an English Sangha arose. Steps were soon taken to implement this. From Manchester he organised the first vipassanā meditation seminars later developing into courses of two weeks every year. It was at one of the early weekend courses that the English Sangha Trust was brought into being.

On the 16th Nov 1955, the first inaugural meeting of the English Sangha Trust took place (M-EST), it was incorporated on the 1st May 1956. The first committee were as follows:-

• Cyril John Bartlett (Chairman),

• Reginald Charles Howes (Secretary),

• Albert Ernest Allen (Treasurer),

• Hans Gunther Mynssen,

• Frederick Henry Bradbury,

• Ronald Joseph Browning,

• Mr Marcus acted as Solicitor for the Trust.

Mr Cyril Bartlett served on both the MBS and EST. (MW 55/56) (M-EST). Initially this new trust was heavily supported by the “Dāna fund” set up by the MBS.

On the 14th December 1955, the party of four set out for Thailand, and on 27th January 1956, the triple upasampadā ordination took place at Wat Paknam(AP) with Venerable Chao Khun Bhāvanakosol the officiating Upajjhāya (preceptor). The Venerable Chao Khun Dhammavorodon, who later became Somdet — Vice- Patriarch of Thailand, assisted as Kammavācāya.

The three sāmaṇeras were ordained together in a ceremony reported to be the biggest higher ordination ceremony known in the history of Thailand. Some 10,000 people crowded the monastery ground and its environs to witness history in the making. For history was made; for these three junior bhikkhus and their elder brother, Kapilavaḍḍho, comprising the minimum number required by vinaya to form a quorum, have established the first English Sangha. (This may be technically correct or incorrect as the four English bhikkhus were in Thailand ED) Some reports attribute the attendance of ten thousand people to Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho’s ordination in May 1954 and others to the following ordination of the three English sāmaṇeras in Jan 1956. However, according to Ajahn Paññāvaḍḍho both ceremonies would have attracted similar numbers.

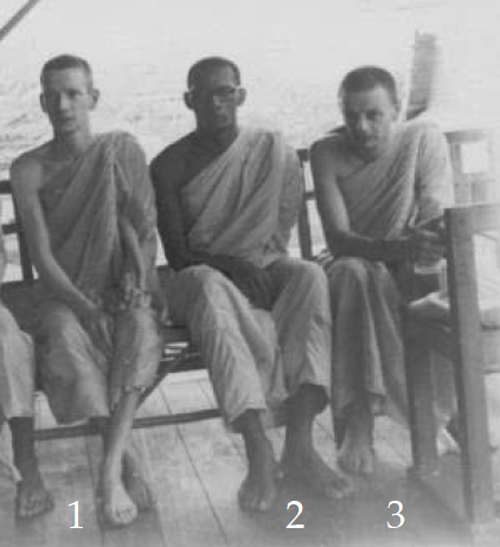

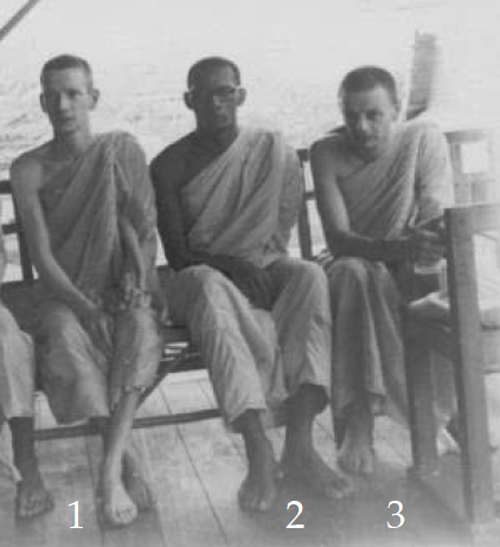

1956. Wat Tartong (Golden Element) Sukhumvit Road, Bangkok

1956. Wat Tartong (Golden Element) Sukhumvit Road, Bangkok

1. Venerable Saddhāvaḍḍho (Robert Albison)

2. Venerable Vijjāvaḍḍho (George Blake)

3. Venerable Paññavaḍḍho (Peter Morgan)It will be of interest to English Buddhists to note the special tribute paid to one of their number on this occasion by the nomination of Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho Bhikkhu by the Mahā-Saṅgha of Thailand to act as anusāsanācariya (second assistant to the upajjhāya) for the ceremony. A duty customarily performed by a qualified bhikkhu of not less than ten years in the Order. A bhikkhu of fewer years may be elected to this rank only if he possesses not less than five special qualities as laid down in the vinaya rules; he must, for example, be thoroughly fit to instruct in bhāvanā and Dhamma. Kapilavaḍḍho had not yet completed his third vassa as a bhikkhu. Further more, as the strong discipline of the Sangha in Thailand necessitates the signatures of the Sangha Rāja and H.M. the King of Thailand as qualifying authorities to this nomination, English Buddhists can be justly proud of the honour conferred on one of their brothers. The three new bhikkhus retained the names given them in London: Saddhāvaḍḍho, Vijjāvaḍḍho and Paññāvaḍḍho.

The Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho returned to England alone on 21st March 1956 and resumed his work of teaching and spreading the Dhamma.

“As to the method of meditation that the Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho taught, there are two avenues of thought. Certainly he taught the Wat Paknam method at first. However it is possible that on returning to England from Thailand in March 1956 he could have taught the Mahāsī method of vipassanā meditation (Mahāsī Sayādaw method was available in Thailand from 1952). The extract below supports this:” (ED)

“History has again been made by the Buddhist Society, Manchester when they organised a summer meditation week. From the 11th to the 18th August sixteen people undertook a week’s strict training in Satipaṭṭhāna under the guidance of the Venerable Bhikkhu Kapilavaḍḍho.

Those who have never undertaken a meditation week may like to know what takes place. At the beginning of the week the Venerable Bhikkhu Kapilavaḍḍho gave a talk outlining the procedure, which necessitates every physical movement being undertaken mindfully. Not a limb should be moved without doing it consciously and carefully, thus, walking is slow, and eating is very slow. At the same time, thoughts are carefully watched, and breaks in concentration noted. People stay in their own room, except for meals. No reading is allowed, and as much time as possible is devoted to meditation practice under strict instruction and guidance. Before a session commences the eight precepts are taken, which includes not eating after mid-day.

What are the results? No one can tell you what it is like — you can only experience it, and then know. You cannot fail to learn a great deal. If you want to make real progress in understanding the Dhamma it is advisable that such work should be undertaken, for no amount of intellectual knowledge alone can give real insight and certainty. Dr Suzuki’s words at the beginning of one of his lectures at Gordon Square are the key to the situation. He said, “Throw away all books. For no amount of book learning can give true understanding.”

(Reported by R Howes, MW Nov 1956)

“However, according to Ajahn Paññāvaḍḍho he continued to teach the Wat Paknam method at least until he disrobed in 1957. It could be that he retained the Wat Paknam Method for his own practice and the Mahāsī method for others on retreat. Or it could be that the Wat Paknam method included this slow moving process as well, but I doubt it.

Dr M. Clark, who in 1967 was a disciple of the Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho said that at that time he taught the Mahāsī method, because he had found that the “Wat Paknam” method could have an adverse effect on people’s minds. He suggested that the Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho may have found the Mahāsī method in two books — “The Heart of Buddhist Meditation” by Nyanaponika and “The Way of Mindfulness” by Soma Thera.” (ED)

* * * * *

Walking“RUJING SAID. One of the most essential practices for the training in the monks’ hall is the practice of slow walking. There are many elders here and there nowadays who do not know about this practice. In fact, only a few people know how to do it. To do the slow walking practice you co-ordinate the steps with the breathing. You walk without looking at the feet, without bending over or looking up. You go so slowly it looks like you’re not moving at all. Do not sway when you walk. Then he walked back and forth several times in the Great Light Storehouse Hall to show me how to do it and said to me; nowadays I am the only one who knows this slow walking practice. If you ask elders in different monasteries about it, I’m sure you’ll find they don’t know it.”

I ASKED. The nature of all things is either good, bad, or neutral. Which of these is the Buddha Dhamma?

RUJING SAID. The Buddha Dhamma goes beyond these three.

I ASKED. The wide road of the Buddhas and ancestors cannot be confined to a small space. How can we limit it to something as small as the “Zen school”?

RUJING REPLIED. To call the wide road of the Buddhas and ancestors “the Zen school” “is thoughtless talk. “The Zen school” is a false name used by baldheaded idiots, and all sages from ancient times are aware of this.

Tiantong Rujing: [Tendo Nyojo] 1163-1228, China. A dharma heir of Xuedou Zhijian, Caodong School. Taught at Qingliang Monastery, Jiankang (Jiangsu), at Ruiyan Monastery, Tai Region (Zhejiang) and at Jingci Monastery, Hang Region (Zhejiang). In 1225 he became abbot of Jingde Monastery, Mt. Tiantong, Ming Region (Zhejiang), where he transmitted dharma to Dogen.

Source: Enlightenment Unfolds, edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi. (C) 1999 by San Francisco Zen Centre. Reprinted by arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc., Boston,

http://www.shambhala.com* * * * *

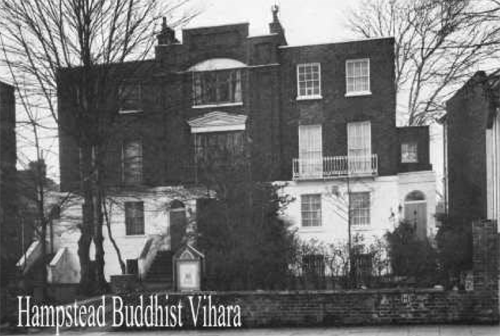

A flat was rented in June 1956 at 10 Orme Court, Bayswater, followed by leasing a house in December 1956 at 50 Alexandra Road, Swiss Cottage. The monthly journal Sangha was started under the editorship of Ruth Lester.

Picture of the First Published Magazine

Picture of the First Published Magazine

Source: Sangha MagazineIn April 1956 Bhikkhu Saddhāvaḍḍho returned to England and disrobed. In June, news arrived that Bhikkhu Vijjāvaḍḍho was ill, so Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho went to Thailand. He returned to England with the Bhikkhus Vijjāvaḍḍho and Paññāvaḍḍho. Shortly after this, the Venerable Vijjāvaḍḍho disrobed.

The Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho lectured in Europe. Whilst in Germany, he met Dr Lisa Schroeder (philosophy) and twin brothers Walter and Gunther Kulbarz who later came to stay with him in England. Dr Lisa Schroeder became Upāsikā Cintavāsī and the twins became Sāmaṇeras Saññāvaḍḍho and Sativaḍḍho. Arthur Wooster became Sāmaṇera Ñāṇavaḍḍho (see page 105 ED). Venerable Paññāvaḍḍho lived in Sale, Cheshire in charge of the Manchester Buddhist Society for some four or five months.

The pace never slackened and his output of work, writing, teaching, and administration grew. His weekly itinerary was exhausting, almost every weekend he would be in Manchester with a program of classes, talks, and interviews which started at noon on the Saturday and continued usually (quite literally) right through until we took him to his train early on Monday morning. What breaks there were, were for food and a half-hour rest between activities. He went immediately to Leeds, then to Oxford, Cambridge, and Brighton and back to London. To my knowledge he seldom slept more than three hours a night. He would meditate, study, and write throughout the usual hours for sleep and his day was filled by teaching and travelling.

Obviously such a pace could not continue without effect, even allowing for his iron constitution and a similar will to drive it to its limits. His health rapidly deteriorated. He became almost blind at one point and finally he retired from the Order in June 1957, having been given an average estimate of one month to live by four independent doctors, fortunately the doctors were wrong. To preserve his anonymity, he did not revert to the name of William Purfurst, becoming instead Richard Randall. At first he was nursed though the critical stage of his illness by Ruth Lester, who had edited Sangha from its inception. Presently, she became Ruth Randall and the time was to come when he was restored to health and devote his time and strength (apart from holding down a strenuous job) to nursing her in the grievous illness that had befallen her. Ten years elapsed during which time the Buddhist community in Britain knew nothing of the whereabouts of the man who had been Bhikkhu Kapilavaḍḍho.

Sources: The above has been compiled mainly from articles written by Maurice Walshe and John Garry (see chronology) on Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho. However additional information has been added to this from other sources.

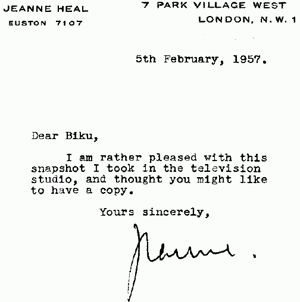

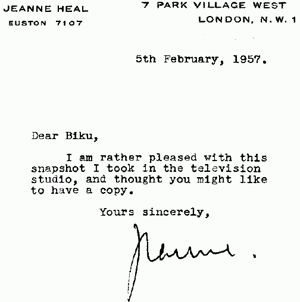

JEANNE HEAL

JEANNE HEAL

7 PARK VILLAGE WEST

LONDON, N.W. 1

EUSTON 7107

5th February, 1957.

Dear Biku,

I am rather pleased with this snapshot I took in the television studio, and thought you might like to have a copy.

Yours sincerely,

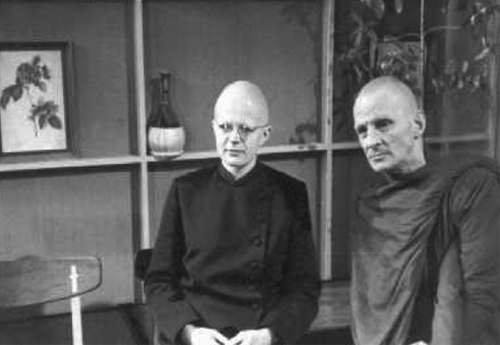

Jeanne Upāsikā Cintavāsī formerly Dr Lisa Schroeder (philosophy)

Upāsikā Cintavāsī formerly Dr Lisa Schroeder (philosophy)

Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho

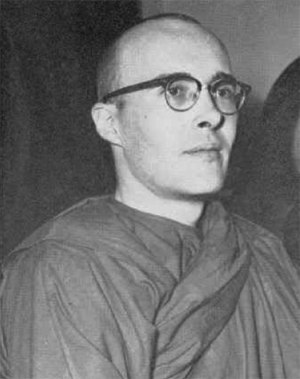

Source: Alan James, Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho scrapbook, Aukana Trust"Manchester Evening News"

21st Sept 1956

Monk Morgan Brings Buddha to the North West

Bhikkhu Pannavaddho (formerly Peter Morgan) sits beside a Buddha statue at the house in Grosvenor Square, Sale where he lives.

Bhikkhu Pannavaddho (formerly Peter Morgan) sits beside a Buddha statue at the house in Grosvenor Square, Sale where he lives.

Evening news reporter

In the front room in a quiet, leafy, Sale, Cheshire road, sits a young man of history. For he is the first resident minister in the English provinces of a world religion born about 2,400 years ago.

Peter Morgan was the Christening name given to Bhikkhu (monk) Pannavaddho, aged 30 who once worked as an electrical engineer. He spent most of his life in Llanelly, Carmarthenshire.

Then he picked up a booklet on Buddhism. It interested him…and in January this year he was ordained as a bhikkhu in Thailand.

Now Pannavaddho (Pali for “He who spreads and increases wisdom”) has only eight worldly possessions — and exactly 227 rules of life.

HE OWNS: Three robes, a begging bowl, razor, water strainer, needle and cotton.

He is maintained by the small but growing Manchester Buddhist community. His rules forbid him to possess or handle money.

Source: Alan James, (Aukana Trust) Venerable Kapilavaḍḍho scrapbook* * * * *

People all over the world who are interested in Buddhism and keep in touch with its news and activities must have heard of the Buddha Jayanti celebrations held a few years ago in all Buddhist countries, including India and Japan. It was in 1957 or, according to the reckoning of some Buddhist countries, in 1956, that Buddhism, as founded by Gotama the Buddha, had completed its 2,500th year of existence. The Buddhist tradition especially of the Theravāda or Southern School such as now prevails in Burma, Ceylon, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand, has it that on the completion of 2,500 years from its foundation, Buddhism would undergo a great revival. Resulting in its all-round progress, in both the fields of study and practice. Buddhists throughout the world, therefore, commemorated the occasion in 1956-57 by various kinds of activities such as meetings, symposiums, exhibitions and the publication of Buddhist texts and literature.

Source: (Ebooks buddhanet.net) “Buddhism in Thailand Its Past and its present” by Karuna Kusalasaya. First published by Buddhist Publication Society 1965