Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/31/24

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organisat ... tionalists

(Redirected from Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists)

Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists

Організація українських націоналістів

Emblem of OUN-M

Emblem of OUN-B

Leader: Andriy Melnyk (conservative)[1]; Stepan Bandera (militant)

Foundation: 1929; 95 years ago

Ideology: Integral nationalism[2][3][4]; Corporate statism[5]; Ukrainian irredentism[6]; Ethnocracy[10][11]

Faction: Banderite (from Feb. 1940)[12]

Political position: Far-right

Slogan: "Slava Ukraini! Heroiam slava!"[13]

"March of Ukrainian Nationalists" (anthem)[14]

Major actions: Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

Notable attacks: Killing of Bronisław Pieracki

Size: 20,000 (1939 est.)[15][16]: 105

Part of: Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations

Allies: Ukrainian Insurgent Army (paramilitary wing)

Flag

Preceded by: Ukrainian Military Organization; League of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN; Ukrainian: Організація українських націоналістів, romanized: Orhanizatsiia ukrainskykh natsionalistiv) was a Ukrainian nationalist organization established in 1929 in Vienna, uniting the Ukrainian Military Organization with smaller, mainly youth, radical nationalist right-wing groups. The OUN was the largest and one of the most important far-right Ukrainian organizations operating in the interwar period on the territory of the Second Polish Republic.[17][18] The OUN was mostly active preceding, during, and immediately after the Second World War. Its ideology has been described as having been influenced by the writings of Dmytro Dontsov, from 1929 by Italian fascism, and from 1930 by German Nazism.[19][20][21][22][23][24] The OUN pursued a strategy of violence, terrorism, and assassinations with the goal of creating an ethnically homogenous and totalitarian Ukrainian state.[23][25]

During the Second World War, in 1940, the OUN split into two parts. The older, more moderate members supported Andriy Melnyk's OUN-M, while the younger and more radical members supported Stepan Bandera's OUN-B. On 30 June 1941 OUN-B declared an independent Ukrainian state in Lviv, which had just come under Nazi Germany's control in the early stages of the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union.[26] OUN-B pledged to work closely with Germany, which was described as freeing the Ukrainians from Soviet oppression, and OUN-B members subsequently took part in the Lviv pogroms.[27] In response to the OUN-B declaration of independence, the Nazi authorities suppressed the OUN leadership. Members of the OUN took an active part in the Holocaust in Ukraine and Poland. In October 1942, OUN-B established the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA).[nb 1] In 1943–1944, in an effort to prevent Polish efforts to re-establish prewar borders,[35] UPA units carried out massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.[26]

In the course of the war, with the approaching defeat of Nazi Germany, the OUN-B changed its political image, exchanging fascist symbolism and totalitarianism for democratic slogans.[36] After World War II, the UPA fought Soviet and Polish government forces. In 1947, in Operation Vistula, the Polish government deported 140,000 Ukrainians as part of the population exchange between Poland and Soviet Ukraine.[37] Soviet forces killed 153,000, arrested 134,000, and deported 203,000 UPA members, relatives, and supporters.[26][nb 2] During and after the Cold War, Western intelligence agencies, including the CIA, covertly supported the OUN.[38] A contemporary organization that claims to be the same Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists is still active in Ukraine.

History

Background and creation

Further information: Ukrainian Military Organization

Yevhen Konovalets, the OUN's leader from 1929 to 1938

In 1919, with the end of the Polish–Ukrainian War, the Second Polish Republic took over most of the territory claimed by the West Ukrainian People's Republic and the rest was absorbed by the Soviet Union. One year later, exiled Ukrainian officers, mostly former Sich Riflemen, founded the Ukrainian Military Organization (Ukrainian – Українська Військова Організація: Ukrayins'ka Viys'kova Orhanizatsiya, the UVO) [UVO], an underground military organization with the goals of continuing the armed struggle for independent Ukraine.[39] The UVO was strictly a military organization with a military command structure. Originally the UVO operated under the authority of the exiled government of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic, but in 1925 following a power struggle all the supporters of the exiled president Yevhen Petrushevych were expelled from the organization.[40]

Symon Petliura (center) and Colonel Yevhen Konovalets (to Petliura's right) taking the oath of office of the Sich Riflemen training school in Starokostiantyniv, 1919

The UVO leader was Yevhen Konovalets, the former commander of the elite Sich Riflemen. West Ukrainian political parties secretly funded the organization. The UVO organized a wave of sabotage actions in the second half of 1922, when Polish settlers were attacked, police stations, railroad stations, telegraph poles and railroad tracks were destroyed. An attempt to assassinate Poland's Chief of State Józef Piłsudski was made in 1921. In 1922, they organized 17 attacks on Polish officials, 5 of whom were killed, and 15 attacks on Ukrainians, whom they considered traitors, 9 of whom died, among them Sydir Tverdokhlib.[41]

UVO continued this type of activity, albeit on a smaller scale later. When the League of Nations recognized Polish rule over western Ukraine in 1923, many members left the UVO.[citation needed] The Ukrainian legal parties turned against the UVO's militant actions, preferring to work within the Polish political system. As a result, the UVO turned to Germany and Lithuania for political and financial support. It established contact with militant anti-Polish student organizations, such as the Group of Ukrainian National Youth, the League of Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Union of Ukrainian Nationalist Youth. After preliminary meetings in Berlin in 1927 and Prague in 1928, at the founding congress in Vienna in 1929 the veterans of the UVO and the student militants met and united to form the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). Although the members consisted mostly of Galician youths, Yevhen Konovalets served as its first leader and its leadership council, the Provid, comprised mostly veterans and was based abroad.[42][43]

Pre-war activities

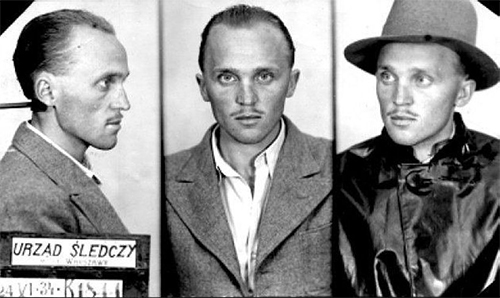

See also: Pacification of Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia (1930) and Assassination of Bronisław Pieracki

Prior to World War II, the OUN was smaller and less influential among the Ukrainians minority in Poland than the moderate Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance.[44][45] The OUN sought to infiltrate legal political parties, universities, and other political structures and institutions.[25][26][nb 3] OUN ideology was influenced by several political theorists,[19] such as Dmytro Dontsov, whose political thought was characterised by totalitarianism, national chauvinism, and antisemitism, as well as Mykola Stsiborskyi and Yevhen Onatsky [uk], and Italian fascism and German Nazism.[46][47][48] OUN nationalists were trained by Benito Mussolini in Sicily jointly with the Ustase, they also maintained offices in Berlin and Vienna.[49] Before the war, the OUN regarded the Second Polish Republic as an immediate target, but viewed the Soviet Union, although not operating on its territory, as the main enemy and greatest oppressor of the Ukrainian people.[50] Even before the war, impressed by the successes of fascism, OUN radicalised its stance, and it saw Nazi Germany as its main ally in the fight for independence.[51]

In contrast to UNDO, the OUN accepted violence as a political tool against foreign and domestic enemies of their cause. Most of its activity was directed against Polish politicians and government representatives. Under the command of the Western Ukrainian Territorial Executive (established in February 1929), the OUN carried out hundreds of acts of sabotage in Galicia and Volhynia, including a campaign of arson against Polish landowners (which helped provoke the 1930 Pacification), boycotts of state schools and Polish tobacco and liquor monopolies, dozens of expropriation attacks on government institutions to obtain funds for its activities, and assassinations. From 1921 to 1939 UVO and OUN carried out 63 known assassinations: 36 Ukrainians (among them one communist), 25 Poles, 1 Russian and 1 Jew.[52] This number is likely an underestimate because there were likely unrecorded killings in rural regions.[53]: 45

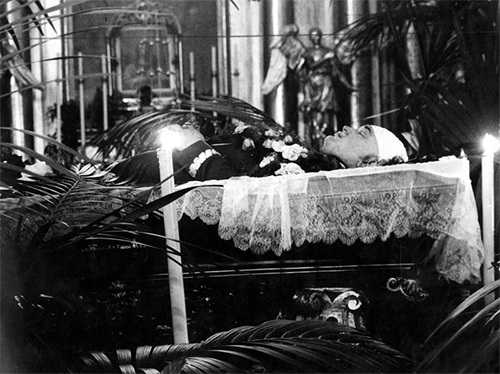

The corpse of Bronisław Pieracki on 18 June 1934

The OUN's victims during this period included Tadeusz Hołówko, a Polish promoter of Ukrainian-Polish compromise, Emilian Czechowski, Lwow's Polish police commissioner, Alexei Mailov, a Soviet consular official killed in retaliation for the Holodomor, and most notably Bronisław Pieracki, the Polish interior minister. The OUN also killed moderate Ukrainian figures such as the respected teacher (and former officer of the Ukrainian Galician Army) Ivan Babij. Most of these killings were organized locally and occurred without the authorization or knowledge of the OUN's emigre leaders abroad.[53] In 1930 OUN members assaulted the head of the Shevchenko Scientific Society Kyryl Studynsky in his office.[54] Such acts were condemned by the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Metropolitan Andriy Sheptytsky, who was particularly critical of the OUN's leadership in exile who inspired acts of youthful violence, writing that they were "using our children to kill their parents" and that "whoever demoralizes our youth is a criminal and an enemy of the people."[55] OUN's terrorist methods, fascination with fascism, rejection of parliamentary democracy and acting against Poland on behalf of Germany did not find support among many other Ukrainian organizations, especially among the Petlurites, i.e. former activists of the Ukrainian People's Republic.[56]

As the Polish state's repressive policies with respect to Ukrainians during the interwar period increased, many Ukrainians (particularly the youth, many of whom felt they had no future) lost faith in traditional legal approaches, in their elders, and in the western democracies who were seen as turning their backs on Ukraine. The young were much more radical, calling for the use of terror in political struggle, but both groups were united by national radicalism and advocacy of a totalitarian system.[57] The leader of the "old" group Andriy Melnyk claimed in a letter sent to the German minister of foreign affairs Joachim von Ribbentrop on 2 May 1938 that the OUN was "ideologically akin to similar movements in Europe, especially to National Socialism in Germany and Fascism in Italy".[58] This period of disillusionment coincided with the increase in support for the OUN. By the beginning of the Second World War, the OUN was estimated to have 20,000 active members and many times that number of sympathizers. Many bright students, such as the talented young poets Bohdan Kravtsiv [uk] and Olena Teliha (executed by the Nazis at Babi Yar) were attracted to the OUN's revolutionary message.[43]

As a means to gain independence from Polish and Soviet oppression, before World War II the OUN accepted material and moral support from Nazi Germany. The Germans, needing Ukrainian assistance against the Soviet Union, were expected by the OUN to further the goal of Ukrainian independence. Although some elements of the German military were inclined to do so, they were ultimately overruled by Adolf Hitler and his political organization, whose racial prejudice against the Ukrainians and desires for economic exploitation of Ukraine precluded cooperation.[citation needed] The interwar Lithuanian government had particularly close ties with the OUN.[59]

During World War II

See also: Occupation of Poland (1939–1945)

Split in the OUN

In September 1939 Poland was invaded and split by Germany and the Soviet Union. On 1 November 1939, Polish territories annexed by the Soviet Union (i.e. Volhynia and Eastern Galicia) were incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Initially, the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland was met with limited support from the ethnic Ukrainian population. Repression was directed mainly against the ethnic Poles, and the Ukrainisation of education, land reform, and other changes were popular among the Ukrainians. The situation changed in the middle of 1940 when collectivisation began and repressions hit the Ukrainian population. There were 2,779 Ukrainians arrested in 1939, 15,024 in 1940 and 5,500 in 1941, until the German invasion of the Soviet Union.[60]

The situation for ethnic Ukrainians under German occupation was much better. About 550,000 Ukrainians lived in the General Government in the German-occupied portion of Poland, and they were favoured at the expense of Poles. Approximately 20 thousand Ukrainian activists escaped from the Soviet occupation to Warsaw or Kraków.[61] In late 1939, Nazi Germany accommodated OUN leaders in the city of Kraków, the capital of the General Government and provided a financial support for the OUN.[62][63] The headquarters of the Ukrainian Central Committee headed by Volodymyr Kubiyovych, the legal representation of the Ukrainian community in the Nazi zone, were also located in Kraków.[64][65]

Stepan Bandera

Andriy Melnyk

Despite the differences, the OUN's leader Yevhen Konovalets was able to maintain unity within the organization. Konovalets was assassinated by a Soviet agent, Pavel Sudoplatov, in Rotterdam in May 1938. He was succeeded by Andriy Melnyk, a 48-year-old former colonel in the army of the Ukrainian People's Republic and one of the founders of the UVO. He was chosen to lead the OUN despite not having been involved in activities throughout the 1930s. Melnyk was more friendly to the Church than any of his associates (the OUN was generally anti-clerical), and had even become the chairman of a Ukrainian Catholic youth organization that was regarded as anti-nationalist by many OUN members. His choice was seen as an attempt by the leadership to repair ties with the Church and to become more pragmatic and moderate. However, this direction was opposite to the trend within western Ukraine itself.[66]

Bandera's Second OUN Conference resolutions legalised the existence of Bandera's OUN. OUN leader Andriy Melnyk denounced it as "saboteur".

In Kraków on 10 February 1940 a revolutionary faction of the OUN emerged, called the OUN-R or, after its leader Stepan Bandera, the OUN-B (Banderites). This was opposed by the current leadership of the organization, so it split, and the old group was called OUN-M after the leader Andriy Melnyk (Melnykites). The OUN-M dominated Ukrainian emigration and the Bukovina, but in Ukraine itself, the Banderists gained a decisive advantage (60% of the agent network in Volhynia and 80% in Eastern Galicia).[67] Political leader Transcarpathian Ukrainians Avgustyn Voloshyn praised Melnyk as a Christian of European culture, in contrast to many nationalists who placed the nation above God.[68] OUN-M leadership was more experienced and had some limited contacts in Eastern Ukraine; it also maintained contact with German intelligence and the Germany army.[69] OUN-B consisted mainly of Galician youth, who were earlier shut out of the leadership. It had a strong network of devoted followers and was powerfully aided by Mykola Lebed, who began to organize the feared Sluzhba Bezpeky or SB,[citation needed] a secret police force modelled on the Cheka with a reputation for ruthlessness.[citation needed]

Early years of the war and activities in Central and Eastern Ukraine

An OUN-B leaflet from the World War II era

On 25 February 1941, the head of Abwehr Wilhelm Franz Canaris sanctioned the creation of the "Ukrainian Legion". Ukrainian Nachtigall and Roland battalions were formed under German command and numbered about 800 men.[70] OUN-B expected that it would become the core of the future Ukrainian army. The OUN-B already in 1940 began preparations for an anti-Soviet uprising. However, Soviet repression delayed these plans and more serious fighting did not occur until after the German invasion of the USSR in July 1941. According to OUN-B reports, they then had about 20,000 men grouped in 3,300 locations in Western Ukraine.[71] The NKVD [Russian Interior Ministry] was determined to liquidate the Ukrainian underground, according to Soviet reports 4435 members were arrested between October 1939 and December 1940.[72] There were public trials and death sentences were carried out. In the first half of 1941, 3073 families (11329 people) of members of the Polish and Ukrainian underground were deported from Eastern Galicia and Volhynia.[73] Soviet repression forced about a thousand members of the Ukrainian underground to take up partisan activities even before the German invasion.[74]

After Germany's invasion of the USSR, on 30 June 1941, OUN seized about 213 villages and organized diversion in the rear of the Red Army. In the process, it lost 2,100 soldiers and 900 were wounded.[75] The OUN-B formed Ukrainian militias that, displaying exceptional cruelty, carried out antisemitic pogroms and massacres of Jews.[76][77][78] The biggest pogroms in which Ukrainian nationalists were complicit took place in Lviv in two waves in June–July 1941, involving OUN-B activists, German military and paramilitary personnel, Ukrainian, and to a lesser extent Polish urban residents and peasants from the nearby countryside, and in the later wave the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police.[79][80] Estimates of Jewish deaths in these events range between 4,000 (Dieter Pohl),[81] 5,000 (Richard Breitman),[82] and 6,000 (Peter Longerich).[83] The involvement of OUN-B is unclear, but certainly OUN-B propaganda fuelled antisemitism.[84] The vast majority of pogroms carried out by the Banderites occurred in Eastern Galicia and Volhynia.[85]

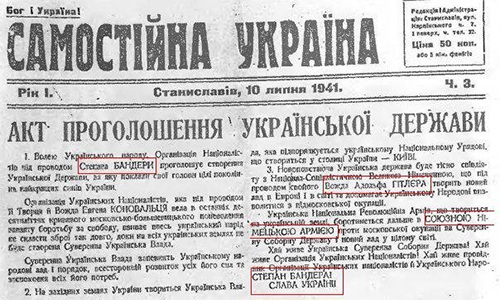

One of the versions of the "Act of Proclamation of Ukrainian State" signed by Stepan Bandera

Eight days after Germany's invasion of the USSR, on 30 June 1941, the OUN-B proclaimed the establishment of Ukrainian State in Lviv, with Yaroslav Stetsko as premier. In response to the declaration, OUN-B leaders and associates were arrested and imprisoned by the Gestapo (circa 1500 persons).[86] Many OUN-B members were killed outright or perished in jails and concentration camps (both of Bandera's brothers were eventually murdered at Auschwitz). On 18 September 1941, Bandera and Stetsko were sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp in "Zellenbau Bunker", where they were kept until September 1944. While imprisoned, Bandera received help from the OUN-B including financial assistance. The Germans permitted the Ukrainian nationalists to leave the bunker for an important meeting with OUN representatives in Fridental Castle which was 200 meters from Sachsenhausen.[87][verify]

As a result of the German crackdown on the OUN-B, the faction controlled by Melnyk enjoyed an advantage over its rival and was able to occupy many positions in the civil administration of former Soviet Ukraine during the first months of German occupation. The first city which it administered was Zhitomir, the first major city across the old Soviet-Polish border. Here, the OUN-M [Melnyk's OUN-M] helped stimulate the development of Prosvita societies, the appearance of local artists on Ukrainian-language broadcasts, the opening of two new secondary schools and a pedagogical institute, and the establishment of a school administration. Many locals were recruited into the OUN-M. The OUN-M also organized police forces, recruited from Soviet prisoners of war. Two senior members of its leadership, or Provid, even came to Zhitomir. At the end of August 1941, however, they were both gunned down, allegedly by the OUN-B which had justified the assassination in their literature and had issued a secret directive (referred to by Andriy Melnyk as a "death sentence") not to allow OUN-M leaders to reach Ukrainian SSR's capital Kiev (now Kyiv, Ukraine). In retaliation, the German authorities, often tipped off by OUN-M members, began mass arrests and executions of OUN-B members, to a large extent eliminating it in much of central and eastern Ukraine.[88]

According to the Nuremberg Trials documents, on 25 November 1941 Einsatzgruppe C5 received an order to "quietly liquidate" members of "Bandera-Movement" as it was confirmed that they were preparing a rebellion in the Reichskomissariat with the goal of establishing independent Ukraine.[89]

As the Wehrmacht moved East, the OUN-M established control of Kiev's civil administration; that city's mayor from October 1941 until January 1942, Volodymyr Bahaziy, belonged to the OUN-M and used his position to funnel money into it and to help the OUN-M take control over Kiev's police.[90] The OUN-M also initiated the creation of the Ukrainian National Council in Kiev, which was to become the basis for a future Ukrainian government.[91] At this time, the OUN-M also came to control Kiev's largest newspaper and was able to attract many supporters from the central and eastern Ukrainian intelligentsia. Alarmed by the OUN-M's growing strength in central and eastern Ukraine, the German Nazi authorities swiftly and brutally cracked down on it, arresting and executing many of its members in early 1942, including Volodymyr Bahaziy, and the writer Olena Teliha who had organized and led the League of Ukrainian Writers in Kiev.[90] Although during this time elements within the Wehrmacht tried in vain to protect OUN-M members, the organization was largely wiped out within central and eastern Ukraine.

A declassified 2007 CIA note summarised the situation as follows:

"The [German] army, which desired the genuine cooperation of the Ukrainians and was willing to allow the formation of a Ukrainian state, was quickly overruled by the [National-Socialist] party and the SS. The Germans used all means necessary to force the cooperation which the Ukrainians were largely unwilling to give. By summer 1941 a battle raged on Ukrainian soil between two ruthless exploiters and persecutors of the Ukrainian people [:] the Third Reich and the Soviet Union. The OUN and the partisan army created in late 1942, the UPA, fought bitterly against both the Germans and the Soviets and most of their respective allies".[92]

OUN-B's fight for dominance in western Ukraine

As the OUN-M was being wiped out in the regions of central and western Ukraine that had been east of the old Polish-Soviet border, in Volhynia the OUN-B, with easy access from its base in Galicia, began to establish and consolidate its control over the nationalist movement and much of the countryside. Unwilling and unable to openly resist the Germans in early 1942, it methodically set about creating a clandestine organization, engaging in propaganda work, and building weapons stockpiles.[93] A major aspect of its programme was the infiltration of the local police; the OUN-B was able to establish control over the police academy in Rivne. By doing so the OUN-B hoped to eventually overwhelm the German occupation authorities ("If there were fifty policemen to five Germans, who would hold power then?"). In their role within the police, Bandera's forces were involved in the extermination of Jewish civilians and the clearing of Jewish ghettos, actions that contributed to the OUN-B's weapon stockpiles. In addition, blackmailing Jews served as a source of added finances.[94] During the time that the OUN-B in Volhynia was avoiding conflict with the German authorities and working with them, resistance to the Germans was limited to Soviet partisans on the extreme northern edge of the region, to small bands of OUN-M fighters, and to a group of guerrillas knowns as the UPA or the Polessian Sich, unaffiliated with the OUN-B and led by Taras Bulba-Borovets of the exiled Ukrainian People's Republic.[93]

By late 1942, the status quo for the OUN-B was proving to be increasingly difficult. The German authorities were becoming increasingly repressive towards the Ukrainian population, and the Ukrainian police were reluctant to take part in such actions. Furthermore, Soviet partisan activity threatened to become the major outlet for anti-German resistance among western Ukrainians. By March 1943, the OUN-B leadership issued secret instructions ordering their members who had joined the German police in 1941–1942, numbering between 4,000 and 5,000 trained and armed soldiers, to desert with their weapons and to join the units of the OUN-B in Volyn.[95] Borovets attempted to unite his UPA, the smaller OUN-M and other nationalist bands, and the OUN-B underground into an all-party front. The OUN-M agreed while the OUN-B refused, in part due to the insistence of the OUN-B that their leaders be in control of the organization.

After negotiations failed, the OUN commander Dmytro Klyachkivsky coopted the name of Borovets' organization, UPA, and decided to accomplish by force what could not be accomplished through negotiation: the unification of Ukrainian nationalist forces under OUN-B control. On 6 July, the large OUN-M group was surrounded and surrendered, and soon afterward most of the independent groups disappeared; they were either destroyed by the Communist partisans or the OUN-B or joined the latter.[93] On 18 August 1943, Taras Bulba-Borovets and his headquarters were surrounded in a surprise attack by an OUN-B force consisting of several battalions. Some of his forces, including his wife, were captured, while five of his officers were killed. Borovets escaped but refused to submit, in a letter accusing the OUN-B of among other things: banditry; of wanting to establish a one-party state; and of fighting not for the people but in order to rule the people. In retaliation, his wife was murdered after two weeks of torture at the hands of the OUN-B's SB. In October 1943 Bulba-Borovets largely disbanded his depleted force in order to end further bloodshed.[96] In their struggle for dominance in Volhynia, the Banderists would kill tens of thousands of Ukrainians for links to Bulba-Borovets or Melnyk.[97]

OUN-B's fight against Germany, Soviet Union and Poland

Further information: Ukrainian Insurgent Army

Further information: Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

Besides armed struggle, according to ICJ documents, OUN-B (referred as "Banderagruppe") has been spreading anti-German propaganda comparing German policy towards Ukrainians with Holodomor.[98]

Further information: Hunger Plan

By the fall of 1943, the OUN-B forces had established their control over substantial portions of rural areas in Volhynia and southwestern Polesia. While the Germans controlled the large towns and major roads, such a large area east of Rivne had come under the control of the OUN-B that it was able to set about creating a "state" system with military training schools, hospitals and a school system, involving tens of thousands of personnel.[99] Its combat organization, the UPA, which came under the command of Roman Shukhevich in August 1943, would fight only limited skirmishes and defensive actions against the Germans. The USSR was considered the primary enemy, and the fight against the Soviets continued until the mid-1950s. It would also play a major role in the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia from western Ukraine.

Towards the end of the war

It is believed that the OUN ordered the assassination of Ukrainian writer Yaroslav Halan in 1949 who was highly critical of the organization.[citation needed]

After the Second World War

See also: Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists

After the war, the OUN in eastern and southern Ukraine continued to struggle against the Soviets; 1958 marked the last year when an OUN member was arrested in Donetsk.[100] Both branches of the OUN continued to be quite influential within the Ukrainian diaspora. The OUN-B was formed in 1943 by an organization called the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations [ABN] (headed by Yaroslav Stetsko). The Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations it created and headed would include at various times emigre organizations from almost every eastern European country with the exception of Poland: Croatia, the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, anti-communist emigre Cossacks, Hungary, Georgia, Bohemia-Moravia (today the Czech Republic), and Slovakia. In the 1970s, the ABN was joined by anti-communist Vietnamese and Cuban organizations.[101] The Lithuanian partisans had particularly close ties with the OUN.[59] In 1956, Bandera's OUN split into two parts,[102] the more moderate OUN(z) led by Lev Rebet and Zinoviy Matla, and the more conservative OUN led by Stepan Bandera.[102]

Euromaidan in Kyiv, December 2013. Protesters with OUN-B flag.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, both OUN factions resumed activities within Ukraine. The Melnyk faction threw its support behind the Ukrainian Republican Party at the time that it was headed by Levko Lukyanenko. The OUN-B reorganized itself within Ukraine as the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists (KUN) (registered as a political party in January 1993[103]). Its conspiratorial leaders within the diaspora did not want to openly enter Ukrainian politics and attempted to imbue this party with a democratic, moderate facade. However, within Ukraine, the project attracted more primitive nationalists who took the party to the right.[104] Until her death in 2003, KUN was headed by Slava Stetsko, widow of Yaroslav Stetsko, who also simultaneously headed the OUN and the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations.

On 9 March 2010, the Kyiv Post reported that the OUN political party[clarification needed] rejected Yulia Tymoshenko's calls to unite "all of the national patriotic forces" led Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko against President Viktor Yanukovych. The OUN political party did demand that Yanukovych should reject the idea of cancelling the Hero of Ukraine status given to Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych, Yanukovych should continue the practice of recognizing fighters for Ukraine's independence, which was launched by (his predecessor) Viktor Yushchenko, and posthumously award the Hero of Ukraine titles to Yevhen Konovalets. [a Ukrainian military commander and political leader of the Ukrainian nationalist movement.[105] On 19 November 2018, Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and fellow Ukrainian nationalist political organizations Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists, Right Sector and C14 endorsed Ruslan Koshulynskyi's candidacy in the 2019 Ukrainian presidential election.[106] In the election Koshulynskyi received 1.6% of the votes.[107]