Part 2 of 2

Vadim (real name withheld two unofficial places of detention in government-controlled territory, exact locations unknown)Pro-Kyiv forces forcibly disappeared Vadim, 39, a real estate agent from Donetsk, in April 2015 next to government-controlled Kurakhove. He spent around six weeks in unacknowledged detention, the first three days on the premises of an alleged base of Right Sector and then on the premises of an alleged SBU base in an unknown location. His interrogators subjected Vadim to various forms of torture.[77]

Detention at checkpoint and transfer to alleged Right Sector baseOn the morning of April 9, 2015, Vadim boarded a Donetsk-bound shuttle bus in government-controlled Slovyansk, where he had spent the previous day on real estate business. At the Georgievsky checkpoint near Kurakhove, checkpoint personnel collected all the passengers’ passports, which is routine checkpoint procedure. A gunman holding Vadim’s passport ordered Vadim to get off the bus with his belongings and instructed the driver to proceed without him.[78]

Three men in camouflaged uniforms without insignia led Vadim into a small cabin at the checkpoint, took away his phone, and searched him thoroughly. When going through his papers, they found a badge identifying him as one of the organizers of the May 2014 separatist referendum in Donetsk. They tied his hands behind his back with his own belt, pulled a bag over his head, pushed him to his knees, called him a “separatist thug,” and questioned him about his connections in Slovyansk. They threw him into the back seat of a car and drove off with him sandwiched between two gunmen.

According to Vadim, after a two-hour drive his captors dragged him out of the vehicle and led him through a gate with a checkpoint next to it. They put Vadim next to a wall in a yard. One of the gunmen punched him hard in his lower back, saying, “Hello from Pumpkin!”[79] At that point, Vadim realized that the detention was related to his acquaintance Marina (not her real name), or “Pumpkin,” who was affiliated with the DNR intelligence service and whose sister, Natalia (not her real name), he was courting at the time. Vadim told Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch that several weeks earlier Natalia had hinted to him that any military activity by the Ukrainian forces he saw during his travels in Ukrainian government-controlled territory would be of interest to her sister. He called Natalia on his way to Slovyansk on April 8 and told her that he had seen several Ukrainian tanks and personnel carriers on the road.

Torture at alleged Right Sector baseAccording to Vadim, his captors handed him over to other Ukrainian gunmen who took him to a basement and interrogated him for hours, asking about his connections with Pumpkin and some other people whose names did not sound familiar. They beat him with sticks on his arms, legs, and back, kicked and punched him, and tortured him with electric shocks. Twenty grams of gold, which he had bought to make a ring, had been found on him, along with some cash a client had paid him in Slovyansk, and the torturers wanted to know where he had his “cache” with money and gold supposedly used for separatist activities. Vadim described his torture in detail:

They attached two stripped wires to my fingers and turned a knob on some kind of device.... There were crackling sounds and electric current went through me. I was howling from pain.… The bag [on my head] was blocking my vision, so I could not see them. They kept asking their questions. One of them demanded I kneel and sing the Ukrainian anthem.... They put out their cigarettes on my back and torso. It must’ve gone on for hours. I lost count of time. Finally, they left me alone, handcuffed to a bar on the wall. In the morning, a guard came up to me, un-cuffed me, gave me some water, and took me to the toilet. He asked if I could move my left hand. I tried and it was clear two fingers were broken.… Then, it started all over again. Judging by their voices, they were different people. They un-cuffed me from the bar, threw me to the floor and kicked me. Then, they cuffed me again and gave me shocks, then they beat me again.[80]

According to Vadim, during a break in the interrogation, a sympathetic guard un-cuffed one of his hands, allowed him to remove the bag, gave him a cigarette, and left him alone for a while. He saw that there was a table in the room, close to where he was tied to the bar, with a sheaf of papers on it. Stretching his free hand, he could look at some of the papers, and realized that his captors had a full print-out of his April 8 telephone conversation with Natalia and what appeared to be his phone billing for a month, with a long list of numbers and names of people who had called him and whom he had called. He recognized some of the names his torturers were inquiring about and understood that they were among the individuals he had been in touch with on real estate business. “As a realtor, I talk to lots of people but I don’t remember their full names, just the properties and their [first] names. So naturally, the interrogators called out those names and said they were separatist something or other, and I had no idea who those people were before seeing that paper,” he said.[81]

According to Vadim, towards the end of his second day of detention, the guards took him to a small, dark shed. He had to crawl to get inside. The ceiling was so low he could not stand straight. The shed had a partition in the middle, and there was another captive behind it. Vadim’s section of the shed had a bed in it, a slop bucket, and a pail of water. The man behind the partition told Vadim that he had been there for two months already and that, from what he could gather from overheard snatches of conversations between guards, they were being held in a Right Sector compound.

Transfer to an unknown locationThe next day, Vadim and the other inmate were given some bread. Then, two gunmen came for Vadim, telling him to put the bag back on and to crawl out of the shed with his hands behind his head. They said they were transferring him “to another place,” and he “would live” provided he was “on his best behavior.”[82]

They hid Vadim on the back seat of a car and drove for about 90 minutes. They brought him to a compound with lots of armed servicemen on the premises and handed him over to the personnel based there. Vadim was marched into a basement where he spent the next several weeks, handcuffed to the radiator by one hand. According to Vadim, the basement was bare, but he talked one of the guards into giving him a woolen blanket to sleep on. Guards took him to interrogations several times, and the interrogators beat him but were not as “vicious” as at his first place of confinement. They also asked him about his trip to Slovyansk, his connection to Pumpkin, his phone conversation with Natalia, his alleged collaborators, and where he was “hiding money and weapons.”[83] His interrogators used an electric shock device on him once but mainly resorted to kicks and punches.

Vadim's head was covered by a bag during interrogations and whenever the guards or other servicemen entered his cell. Often he heard screams of other prisoners under interrogation. Sometimes the guards brought food to him twice a day, sometimes only once a day, and on several occasions they left him without any food for a couple of days. Throughout his six-week confinement, despite his numerous requests, Vadim had only two opportunities to shower and shave. Based on snatches of conversations of the guards and the interrogators he overheard, Vadim believed that he was held in an SBU compound.

According to Vadim, in the early morning of what proved to be the last day of his detention, May 22, 2015, three servicemen entered his cell. One of them, whom Vadim said seemed more senior, had a video camera. He told Vadim to take off the bag and say on camera that he had been “recruited by Natalia, the sister of Marina, code name Pumpkin, to carry out intelligence activities in Ukraine’s territory” and to call on the Ukrainian authorities to hold them both to account.[84] The more senior servicemen indicated that Vadim would be released if he cooperated. Vadim did precisely as asked. The more senior serviceman turned off the camera and instructed Vadim to put the bag back on. Then, the servicemen led him out of the building, hid him on the back seat of a car, and drove for a while, going through several checkpoints. Finally, they stopped and ordered Vadim to get out of the vehicle, lie flat on the ground with his face down and count to a hundred before getting up. They told him they had put 200 UAH (just over US$7) and his passport in his pocket so that he could make his way home.

A few minutes after they left, Vadim got up, finding himself next to a major road, and managed to flag a taxi. The driver told him it was nearly 8 a.m. on May 22 and he was close to Kurakhove. On May 23, he returned to Donetsk, where he was promptly detained by DNR security services on suspicion of having been recruited by Ukraine’s SBU.

IV. Disappearances, Incommunicado Detention, Ill-treatment and Torture in Separatist-Controlled Areas

OverviewAmnesty International and Human Rights Watch documented nine cases in which Russia-backed separatists held civilians in arbitrary, incommunicado detention for weeks or months without charge and, in most cases, subjected them to ill-treatment. Six of these cases are documented below.[85]

Four of the six individuals were detained in 2015 and two in early 2016. At the end of June 2016, two of the six individuals remained in custody, awaiting trial. The others were released, most of them in exchange for individuals held by Ukrainian authorities.

De facto authorities accused the six of, variously, spying for the Ukrainian government, possessing weapons, and membership of pro-Ukrainian “extremist” organizations.

The facilities where de facto authorities held these individuals include: in Donetsk, the former SBU building currently used by DNR defense structures; the headquarters of what is known as the Ministry of State Security (in the Russian abbreviation, MGB) in the former location of the Donetsk Administrative Appeals Court; the Donetsk State Financial Inspection office; the Donetsk Tax Inspectorate; and in Luhansk, on the premises of the MGB (formerly the tax inspectorate building) and on the grounds of the local bullet factory.

After the DNR authorities or the LNR authorities finally “charged” the individuals, either on clearly fabricated evidence or without any tangible evidence at all, they were transferred to remand prisons, where some of them were allowed access to a lawyer. At time of writing, two of the six were still detained in the Donetsk pre-trial detention facility, awaiting trials that, in the absence of a functional criminal justice system, stand little chance of being fair. One of the six, the leader of a Donetsk-based humanitarian organization, was expelled from DNR-controlled territory. Another was released without charge after over two months of detention. Two others were released by LNR as part of “prisoner exchange” with the Ukrainian government.

Lack of access for independent monitorsIn its most recent Ukraine report, OHCHR spoke of new allegations of killings, arbitrary detention and torture in the areas controlled by DNR and LNR and deplored the de facto authorities’ refusal to grant OHCHR “access to places of deprivation of liberty on the territories they control.”[86]

Representatives of other international organizations, including the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, also expressed to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch their regrets about not having access to places of detention in DNR- and LNR-controlled territories. Nils Muižnieks, the High Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, noted in his report of a visit in March 2016 that relevant interlocutors in Donetsk told him that the “‘local legislation’ does not at present allow for this kind of supervision of the places of detention.”[87] As of the end of June 2016, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) also had no access to places of detention in DNR and LNR.

Local regulations governing the detention of criminal suspects in DNR and LNRThe de facto authorities in DNR have issued regulations that delegate powers of detention on a variety of grounds to locally-created structures. For example, a special DNR cabinet decree allows the MGB to hold individuals for up to 30 days without charge.[88] In some of the cases documented below, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch reviewed materials—letters from the prosecutor’s office and the like—that referred specifically to DNR Cabinet Decree #34, of August 8, 2014, “On emergency measures aimed at protecting the public from banditry and other manifestations of organized crime.”[89] Also, a DNR law “On the Ministry of State Security” states that this agency may administratively detain people who try to enter “specially protected territories with secure facilities, restricted [areas] and other protected objects, and check identity papers, demand explanations, conduct a body search, check and confiscate personal belongings and documents.”[90]

In LNR, the work of security services is regulated by a special decree entitled “Temporary Regimen for the Work of State Security Agencies in the Luhansk People’s Republic,” issued by the de facto head of the self-proclaimed republic, which gives the local MGB overwhelmingly broad powers and authority.[91]

Numerous interlocutors in the DNR told Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch that the MGB is “the most powerful and the most feared organization,” which “operates without any checks and balances.”[92] Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch heard a similar assessment of LNR’s MGB from residents of Luhansk.[93]

Abuses in DNR

Yuri (real name withheld; location of detention: Donetsk)Yuri, a 23-year-old blogger, arrived in Makiivka from Kyiv on December 26, 2015 to spend the winter holidays with his father and mother. A former resident of Makiivka, Yuri had moved to Kyiv in 2014, as the conflict was beginning, to continue his higher education there. MGB servicemen detained him on January 4, 2016 at his parents’ apartment in Makiivka. He spent the next two months in incommunicado detention at the MGB headquarters in Donetsk and in early March was “charged” with illegal possession of weapons, based on apparently fabricated evidence. As of the end of June 2016, he was being held in Donetsk remand prison, pending “trial.” He faces up to four years of imprisonment.[94]

Yuri’s father told Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch researchers that his son was home alone when three MGB officers came for him at around 3 p.m. on January 4:

My wife returned home at around 3:30 or 4 p.m. and saw our desktop computer in the hall, next to the door. She entered the living room, and there was our son with three armed servicemen. One was in fatigues, his face concealed by a black mask. The other two were in civilian clothing. Our son’s t-shirt was torn and his face bruised. The servicemen said they were from the MGB. They neither provided any form of identification nor gave their names. They said that they came to take Yuri to their quarters for a conversation.[95]

According to Yuri’s father, MBG officers searched the apartment using two neighbors as witnesses to the search. Yuri’s father arrived at around 5 p.m. when the search was almost over. He and his wife signed a search protocol which indicated that the officers were removing their family desktop computer, Yuri’s cell phone, and several Ukrainian flags Yuri kept in the apartment. The officials did not provide a copy of the protocol. They said that the flags were “bad news” and escorted Yuri downstairs. His mother begged them to allow her to accompany her son, but the officers refused.[96]

Yuri’s parents followed the MGB officials to Donetsk in another car, until the MGB vehicle entered the gates of the MGB headquarters in central Donetsk.

At around 7 p.m., they saw their son being led across the yard by two armed officials. Yuri was handcuffed and a dark hood covered his head. The parents asked the guard at the gate for information. He eventually told them that they should leave because their son would be “held in custody for the next three days.”

Three days later, MGB officers told the parents they were planning to hold Yuri for another week. They allowed food parcels but provided no information as to the grounds for Yuri’s detention. On January 11, his parents filed a petition with the DNR prosecutor’s office asking for an inquiry into the detention of their son. They also met with a representative of the DNR ombudsperson’s office who told them the ombudsperson could not be of any help in this case as “the laws of wartime allowed the MGB to hold people without charge for one month or even up to two if necessary.”

Yuri’s parents continued to visit MGB headquarters every three days, bringing food parcels for their son and pleading for information. They repeatedly asked MGB officials to let them get a lawyer for their son but their requests were denied, as were their requests to see him.

On February 11, they received a letter from the DNR prosecutor’s office saying that Yuri had been detained by the MGB “on suspicion of affiliation with an extremist organization.”[97] The parents asked MGB officials to confirm this, but they refused to provide any information.

Finally, on February 23, Yuri’s parents received a phone call from an MGB investigator who said that Yuri was suspected of being a member of Svoboda party (a right-wing party registered in Ukraine) and of unlawful possession of weapons. The investigator explained that when they had searched Yuri upon his arrival at MGB headquarters they found two hand grenades in his jacket pocket, which he had supposedly brought from Kyiv. He also emphasized that Yuri had confessed to the possession of the grenades.[98]

According to his parents, Yuri was wearing a t-shirt at home, and he put on his jacket only when leaving the apartment with MGB officials after the search, during which no weapons were found. As the grenades were supposedly “found” in the pocket of that jacket, and since it is very unlikely that Yuri would have chosen to wear a jacket to MGB headquarters if it had grenades in the pocket, the MGB’s version of events seems highly questionable. The fact that Yuri confessed to the possession of those grenades gives grounds for concern that the confession may have been coerced under duress, for example through threats or even torture.

On March 2 or 3, the de facto authorities brought charges against Yuri based on his written confession and the supposed physical evidence, i.e. the two grenades, and transferred him to the Donetsk remand prison. Once registered there, Yuri finally got access to a lawyer hired by his parents. The lawyer told the parents that the authorities dropped the charge of membership in an extremist organization and Yuri would go on trial solely for possession of weapons. She also confirmed that Yuri had signed a confession of weapons possession and was not planning to withdraw it. Despite numerous requests by Yuri and his parents, the prison officials have not allowed a family visit. At time of writing, Yuri’s trial was scheduled for later in the summer at the Makiivka court.[99]

Igor Kozlovsky (location of detention: Donetsk)Igor Kozlovsky, 63, spent a month in incommunicado detention following his arbitrary detention on January 27, 2016 and is currently facing charges of illegal weapons possession and, possibly, of espionage.[100] Before his arrest he taught anthropology and humanities at Donetsk University.

Dr. Kozlovsky was known for his pro-Ukrainian views and for having been an active participant in the Donetsk ecumenical prayer marathon for united Ukraine in 2014. At the time of his detention, Dr. Kozlovsky was working on an article about the influence of the armed conflict on religious communities in separatist-controlled territories in eastern Ukraine, with a particular focus on the persecution and consequent exodus of minority groups.

On January 27, 2016 between 2 and 3 p.m., MGB personnel surrounded Kozovsky near his apartment building in Donetsk, threw him into a jeep, and drove off. According to eyewitnesses, six officers stayed behind and forcibly entered Kozlovsky’s apartment.

Dr. Kozlovsky’s son, Svyatoslav (born 1979), who has severe and multiple disabilities, including Down Syndrome and physical paralysis, was alone when MGB personnel entered the apartment. According to Dr. Kozlovsky’s spouse, Valentina Kozlovskaya, Svyatoslav was unable to move and may not have been able to fully understand what was happening. He still experiences trauma and often recalls how “bad men came and made noise.”[101]

Without any regard for Svyatoslav, MGB personnel proceeded to search the apartment. Dr. Kozlovsky’s spouse, who was in Kyiv on business, eventually became worried that Dr. Kozlovsky was not answering her phone calls and called a distant relative, asking her to check the apartment. MGB personnel were still at the apartment when the relative arrived at around 10 p.m. They let her in and allowed her to attend to Svyatoslav’s health needs. They did not introduce themselves but told the woman that Dr. Kozlovsky had been detained.

Valentina Kozlovskaya filed an inquiry with local police immediately upon her return to Donetsk on the evening of January 28, but police told her that the detention “bore the hallmarks of the MGB” and advised her to speak to the MGB.[102] In the morning she went to the MGB compound, where MGB personnel confirmed that Dr. Kozlovsky was in their custody and informed her that a decision had been made to detain him for 30 days. They provided no information as to the reasons behind the detention and did not allow her to see her husband or pass on food and clothing.

Valentina Kozlovskaya filed an inquiry with the MGB regarding her husband’s detention and the unlawful search (MGB personnel had seized all electronic devices, some of the valuables, and most of the documents kept by the Kozlovskys in the apartment). The next day she also filed a complaint with the office of the DNR ombudsperson. For the next two days she made repeated inquiries with the Dontesk remand prison, hoping that her husband would be transferred there.

She also gave an interview to Russian independent Internet-based Dozhd TV.[103]

On January 31, she went back to the MGB where an MGB officer told her that giving interviews was “a bad idea.” He said Dr. Kozlovsky was still in their custody and was being treated well. He told Valentina Kozlovskaya that Dr. Kozlovsky had been detained on account of his connections with “Ukrainian nationalists” and that he had posted some “problematic” comments on social media. He agreed to accept a parcel with food and clothing for Dr. Kozlovsky. Valentina Kozlovskaya was denied access to her husband for next four weeks, and he was unable to speak to a lawyer.[104]

Dr. Kozlovsky was transferred to a remand prison only on February 26, a month after his detention, and charged with membership in an extremist organization and weapon possession. At this time his wife was able to hire a lawyer to represent him. One of Dr. Kozlovsky’s cellmates had a cell phone, so he managed to contact his wife. He told her the MGB kept him in a basement cell in “awful conditions” with only a mattress on the floor and no other conveniences. The guards brought food to him twice a day and took him to the toilet twice a day. He also said that his leg had been “hurt” and was “healing slowly.” According to his wife, he had been in good health before his detention, with no leg injury, and therefore the injury to his leg could only have occurred during his time in the hands of MGB personnel.

Soon after her husband’s transfer to the remand prison, Valentina Kozlovskaya received her first formal response from the MGB regarding her inquiry. The letter, dated February 26 (the day of Kozlovsky’s transfer) and signed by the “acting minister for state security,” stated that Dr. Kozlovsky “had been arrested by DNR’s state security officials through administrative arrest procedure based on paragraphs 1, 3, and 5 of article one, part one, of the August 8, 2014 Decree by DNR Cabinet ‘On emergency measures to protect the public from banditry and other manifestations of organized crime.’”[105]

On March 11, Valentina Kozlovskaya also received a response from the DNR administration in response to her petition to the head of DNR, which informed her that on January 27 Dr. Kozlovsky had been taken under “administrative arrest” for 30 days “on suspicion of [unspecified] crimes provided for by DNR Criminal Code also indicated that the “administrative arrest had been carried out in line with DNR Cabinet Decree ‘On emergency measures’…” The letter also said that on February 26, when his 30 days of “administrative arrest” were about to expire, Dr. Kozlovsky was charged with unlawful acquisition and/or possession of weapons “under Article 256 of DNR Criminal Code.”[106]

In April 2016, Valentina Kozlovskaya, who maintained correspondence with the DNR prosecutor’s office regarding her husband’s case, received a letter from the prosecutor’s office informing her that the charge of membership in an extremist organization had been dropped but the weapon possession charge remained.[107] In June, when discussing exchanges of prisoners with Ukrainian officials at a meeting of the humanitarian sub-group of the tripartite contact group on Donbass at Minsk, DNR representatives mentioned Igor Kozlovsky, saying he was a Ukrainian “spy” and a “weapons-manufacturer.”[108] It is likely that the DNR authorities continue to hold Dr. Kozlovsky as a bargaining chip for exchange purposes.

As of the end of June, Dr. Kozlovsky remained in the Donetsk remand prison. His wife quit her job to become the sole caregiver for their son.[109]

Marina Cherenkova and Responsible Citizens groupMarina Cherenkova is a leading activist and a founding member of Responsible Citizens, a humanitarian group created by activists in DNR-controlled territory in 2014 to coordinate the distribution of humanitarian aid to civilians affected by the war. Operating out of Donetsk, the group established links with Ukrainian and international aid organizations, which made DNR authorities increasingly suspicious.

In early 2016 the MGB detained and expelled five founding members of Responsible Citizens group—Marina Cherenkova, Enrique Menendez, brothers Evheniy and Dmitry Shibalov, and Olga Kosse—from DNR-controlled territory. While the MGB accused the activists of providing intelligence “to western security services,” none of the five was charged with any crime.[110]

On January 29, 2016, the MGB detained Cherenkova, held her for 24 days, and then expelled her. The other three men were expelled on February 2, right after MGB investigators interrogated them, and Olga Kosse was expelled several days later. [111]

In the evening of January 29, MGB officers took Cherenkova from her home to the MGB headquarters. She managed to send a text message to her colleagues that the MGB was detaining her. For the next three days she was forcibly disappeared, as the MGB held her at their premises but denied she was there. Olga Kosse explained: “After we got [Marina’s] text message, we immediately went to the MGB building but they denied that they were holding her, so we were looking everywhere…”[112]

According to Kosse, on February 2, apparently on MGB orders, Cherenkova called Menendez, the Shibalov brothers, and her, and told them to come to the MGB without providing any additional information:

We needed to know what was going on with Marina, so we all did as we were told. They [MGB officials] brought us to the fourth floor of the building, put me in a room by myself and the others into another room. An investigator who introduced himself as Vadim Vasilyevich took my phone and started going through its contents. He asked me about our international partners, our contacts in DNR, what I think of the conflict. Then, a second investigator, who they called Zampolit [a Soviet term for deputy commander in charge of ideology], started threatening me and accusing me of espionage, conspiracy, of preparing another Maydan [anti-government protests].[113]

In the other room, MGB “investigators” also bombarded Menendez and the Shibalov brothers with questions about their international contacts and accused them of espionage. After about seven hours of interrogation, the investigators told the three that they were being “deported from DNR.” MGB personnel drove the three men to their respective homes, gave them 15 minutes to collect their belongings, then took them to the Oleniivka checkpoint and told them to cross to government-controlled territory and never return to DNR.[114]

Meanwhile, Olga Kosse was allowed to return home. One of the MGB “investigators” told her that Cherenkova had been placed under “administrative arrest” for 30 days and allowed her to pass on to her colleague packages with food and clothing.[115] On February 12, however, when Kosse called the investigator to inquire if she could bring another package to the MGB compound, he agreed to accept the package but told Kosse she would be deported on the same day:

I went to the MGB [compound] with another package for Marina. Then, some men in uniforms with automatic rifles, whom I had never seen before, escorted me home, allowed me to pack my belongings, and drove me to the Oleniivka checkpoint. They didn’t show any documents. At the checkpoint, they ordered me to cross [to the government controlled side] and said I was “on the list” and therefore, should make no attempts to come back.[116]

Cherenkova spent the next 10 days in detention at the MGB compound. On February 22, MGB personnel expelled her from DNR-controlled territory in the same manner as her colleagues. In a statement on Cherenkova’s “deportation,” the MGB emphasized that “as a gesture of good will … before the expiration of her term of administrative arrest and without opening a criminal case against her.”[117] The statement also said that “prompt reaction by Ukraine and US representatives to Cherenkova’s arrest serves to confirm that western security services paid special attention to the activities of Cherenkova and her organization” and that she was “used by foreign security services to undermine the security of the [Donetsk People’s] Republic.”[118]

Responsible Citizens had to discontinue its work despite the considerable humanitarian needs of the population.[119] In April 2016, the group resumed humanitarian aid distribution, but only in government-controlled territory of eastern Ukraine.

Vadim (real name withheld, location of detention: Donetsk)Vadim is the 39-year-old realtor from Donetsk whose detention and torture ordeal in government-controlled territory is described above. On May 25, 2015, DNR de facto authorities detained him as soon as he returned home following his release by the Ukrainian side, and he spent over two months in incommunicado detention in an unofficial prison maintained by DNR in the former SBU building in central Donetsk, on suspicion of having been recruited by Ukraine’s SBU while in captivity in government-controlled territory. He was released on August 3, 2015. Representatives from the DNR Defense Ministry’s intelligence unit and the MGB were involved with his prolonged arbitrary detention, which included ill-treatment and beatings.[120]

Incommunicado Detention and TortureOn May 24, 2015, an acquaintance of Vadim’s in Donetsk who was affiliated with the intelligence unit of DNR’s Ministry of Defense told him that DNR intelligence officers needed to debrief him the next day, supposedly “a standard procedure for all those released from Ukrainian captivity.”[121] Vadim complied, forgoing a doctor’s appointment to have a thorough check-up and get a medical record of his torture-related injuries.

On May 25, Vadim arrived at the former SBU building in central Donetsk. A DNR intelligence investigator, who introduced himself as “Dmitry,” asked him a few questions about his experience in captivity and told him he would be taken into custody. He provided no reasons behind this decision.

Vadim was locked in a small cell with three other cellmates, one of whom had a phone on him and let Vadim made a quick call to his mother. Immediately afterwards, several armed men ran into the room screaming, “What the … do you think you’re doing?” They kicked Vadim with booted feet and punched him several times.[122]

Although Vadim had no access to a lawyer and was not allowed any contact with the outside world, the guards at the gate of the building accepted food parcels for him from his mother. The cell was approximately 3.5 square meters in size and accommodated up to four inmates. According to Vadim, some of his cellmates would stay there for a few days, others for two or three weeks; one had already been there for several months, since before Vadim’s detention. Among his cellmates were other suspected “spies,” young men caught drunk after curfew, and an elderly man who left his house after dusk without an ID.

For the next month, the guards took Vadim to several interrogations carried out by the same investigator, Dmitry, and several other armed officials in camouflaged uniforms. The interrogators accused Vadim of having been recruited by Ukrainian forces to spy on DNR forces. According to Vadim, one of them, whom the others addressed as Denis, was particularly vicious. He screamed at Vadim, punched him in the head, kicked him, tore a chain with a cross off his neck, and threatened to kill him.

Vadim told our researchers:

I kept asking them to let me undergo a medical check-up. I explained that it was my intention to file a complaint against Ukraine with the European Court of Human Rights and I needed a full medical record of my injuries, but they would not listen.… They kept accusing me of having been recruited as a spy and spotter for Ukraine. ‘Stop spinning your tales! Why would they return your documents and even give you transportation money, if they haven’t recruited you? Why would they let you go at all? You should better confess if you want to live!’ The physical abuse and the psychological pressure were pretty bad.[123]

Towards the end of June, an investigator from the DNR MGB nicknamed Grandpa [Ded in Russian] interviewed Vadim asking him the same questions as the previous interrogators. When Vadim asked how much longer he would be in custody, the investigator yelled, “As long as necessary! Shut your trap!” Vadim mumbled a sarcastic comment, and the investigator threw himself on Vadim, kicking and punching him and threatening to kill him.

On July 31, another detainee with a phone on him moved into Vadim’s cell. Vadim called his mother, the first contact he had with family or loved one for nearly two months. He found out that unidentified armed men in camouflaged uniforms had searched his office following on his detention and seized all the electronic equipment there.

Vadim’s mother also told him that she had promptly filed inquiries about his detention with the DNR ombudsperson’s office, the DNR prosecutor’s office, and the DNR Ministry of State Security. The latter got back to her with a written response, dated July 14, confirming that Vadim “is held at 62 Schors St. in Donetsk without explanation as to the reasons behind [his] detention.” The letter, which is now on file with Human Rights Watch along with other case-related documents, also indicated that the MGB had forwarded the case file to the DNR military prosecutor’s office “for a procedural decision to be made.” Vadim’s mother also wrote to the DNR military prosecutor, enclosing the MGB letter and asking for her son’s release.

Release and aftermathOn the evening of August 1, a female MGB investigator met with Vadim and told him she got his situation “sorted out” and he was free to go. On August 3, Vadim had his check-up at a hospital in Donetsk. By that time his bruises (those inflicted by Ukrainian servicemen and those inflicted by DNR investigators) had cleared up, but an x-ray confirmed that two fingers on his left hand had been fractured in the recent past.[124]

In December 2015, Vadim lodged an application with the European Court on Human Rights alleging arbitrary detention and cruel and degrading treatment by both Ukrainian forces and the de facto DNR authorities. The case is pending.[125]

Abuses in LNR

Anatoly Polyakov (location of detention: Luhansk)Anatoly Polyakov, 43, a Russian citizen and vocal critic of Vladimir Putin, traveled to Ukraine in 2014 to support the EuroMaydan protests in Kyiv. After the protests ended, he organized anti-war protests in Russia, and in Ukraine participated in a volunteer organization helping civilians affected by the conflict. Unknown individuals seized Polyakov in March 2015 in Luhansk, and he was held in secret detention for more than nine months, during which he was tortured.[126]

Initial detentionPolyakov arrived in Luhansk on March 12, 2015 to facilitate a prisoner exchange between LNR and Ukrainian authorities and organize a transfer of children for medical care to government-controlled territories. He was in LNR at the invitation of representatives of Igor Plotnitski, the de facto head of LNR. On March 14, he was scheduled to meet with Plotnitski but instead was arrested and spent the next nine months in captivity. He told our researchers:

I was heading to my meeting [with Plotnitsky] when someone hit me on the back of the head. I lost consciousness. When I came to, I had a bag on my head, and my hand were handcuffed and locked to a [pipe], and my legs were locked to it by another pair of plastic hand-cuffs, so I could only sit in a crouched position. On that first day, no one talked to me or asked me anything. The next day, interrogators hit me on the head, ears and crotch, talking in Ukrainian, which I don’t speak, and hitting me harder when I didn’t understand.[127]

Initially, Polyakov’s captors told him that they were pro-Ukrainian saboteurs and that they wanted a US$100,000 ransom to release him. They questioned him about his Ukrainian contacts, especially in eastern Ukraine. Polyakov, however, suspected that these men were in fact from LNR security services who resorted to this farce to make him turn over his contacts.[128]

These captors held Polyakov for a month in the basement of an unidentified facility, repeatedly interrogated him and subjected him to vicious beatings and a mock execution. He was often allowed no more than 15-20 seconds in the toilet. At night, his captors removed the cuffs from his legs, and he could sleep on his side while still chained to the pipe by his hands. In the morning, someone would cuff him back in a sitting position.

After about a month a guard told Polyakov that they were going to release him because “people were looking” for him. They put him in a car, drove for several minutes, and threw him out in the street, with the bag still on his head and his hands and legs still cuffed.

Secret detention at bullet factorySeveral men who said they were LNR fighters immediately picked up Polyakov. They accused him of being a Ukrainian spy and took him to another basement prison facility where he would later be subjected to torture during interrogations, including beatings and a mock execution:

They told me that I’m an “information soldier” because I participated in the EuroMaydan and accused me of being an enemy because of my protest activities in Russia. They said that I’m against Putin, so I’m a criminal. They made me write a will and then carried out a mock execution. They told me to write a note to my family, then took me out into the yard, I could hear them recharging, then a bullet swished close to my ear. I was deafened by the shot.[129]

Polyakov was not totally blinded by the bag his captors kept on his head most of the time. After his release months later, having spoken to other former LNR prisoners and residents of Luhansk, Polyakov came to a firm conclusion that the basement where he had spent his second month in captivity is located on the premises of the Lenin bullet factory in Luhansk, which is used as a military base by LNR forces.

After Polyakov had spent a month at the bullet factory, Boris Petrenko, deputy head of the MGB investigative agency, told Polyakov he was being charged with espionage and attempted subversion against LNR. Petrenko then took Polyakov to the local MGB headquarters in the former Ukrainian Tax Inspectorate building in Luhansk. There, Petrenko handed Polyakov a “confession” to sign, in which Polyakov was described as working for the Ukrainian Defense Ministry, planning “terrorist attacks” in LNR and child kidnappings. After Polyakov refused to sign the documents, he was moved from the MGB premises to a remand prison in Luhansk where he shared a cell with 15 detainees, all of them local residents or separatist fighters accused of looting or petty crimes. Polyakov spent a month there, without being interrogated or subjected to ill-treatment. Then, MGB officers returned for Polyakov and, without any explanation, moved him to a basement cell on the MGB premises. Polyakov described his protracted confinement:

The room was very dusty and dark. Sometimes it got so hot, that I had to lie down next to the door, gasping for a breath of air. They never took me out for a walk. My health severely deteriorated because of the earlier beatings—I had several inflamed wounds, with pus coming out of them, but they would not let me see a doctor. Sometimes they brought visitors and paraded me in front of them—look what we have here, the fifth column, a EuroMaydan fighter!”[130]

On July 29, 2015, his captors briefly transferred Polyakov from the MGB basement back to the Luhansk remand prison and told him that he was to be exchanged. That exchange was suspended, however[131], and they returned Polyakov to the MGB basement for another five months before his release on December 29, 2015, most likely in exchange for some captured pro-Russian separatists.

Mariya Varfolomeeva (location of detention: Luhansk)Mariya Varfolomeeva, 31, a freelance journalist from Luhansk, was arrested by LNR security personnel in January 2015 and held for 14 months in incommunicado detention, first on the premises of LNR’s Ministry of Internal Affairs, then on the premises of LNR MGB headquarters before being transferred to the Luhansk remand prison on charges of being a member of an illegal armed group. She was released as part of an exchange with the Ukrainian side in March 2016. Varfolomeeva’s captors repeatedly threatened her with beatings and electric shocks, pushed her roughly, manhandled and harassed her.[132]

On January 9, 2015, LNR security officers caught Varfolomeeva photographing a residential building used by separatist fighters in Luhansk. They accused her of being an artillery spotter for Ukraine, forced her into a car, took her to the building occupied by LNR’s Ministry of Internal Affairs, and kept her there for the night. She recounted:

When they first detained me, they took me to the basement of the Interior Ministry. There, the interrogators showed me batons and electric shocker devices and threatened to use them on me if I don’t tell them what they want to hear. They asked who sent me and how long was I working for the Ukrainians. One of them said that he’d love to hit me if not for me being so thin that I could break.[133]

On January 10, Varfolomeeva’s captors moved her to the MGB building in Luhansk (former Tax Inspectorate building). The guards tried to reassure her that “they don’t torture people there,” but in the hall she saw a man escorted from an interrogation, his face “all bloody and bruised.” During the several weeks that she spent in a basement cell, other inmates described to her how they were tortured by MGB officers who applied electric wires to their earlobes, saying in jest they were making a “a call to [president] Obama.”[134]

On March 27, the LNR MGB announced through its website that a “criminal investigation” into Varfolomeeva’s actions was completed and it “fully proved” that she was a member of Right Sector and a spotter for Ukrainian forces. Around that time, MGB personnel told Varfolomeeva she would be offered for exchange. They also filmed her interrogation and provided the video to Russian TV station Lifenews and LNR television.[135]

Varfolomeeva spent the next year in a women’s cell of the Luhansk remand prison. Most of the time, there were no other female detainees, and Varfolomeeva was on her own. During that time, she was allowed no contact with the outside world, though she regularly received parcels with food and clothing from her father. To the best of her knowledge, LNR authorities never transferred her case to a court. Instead, they sent her on several failed exchanges—on July 29 and November 19, 2015, and on February 26, 2016—and finally released her in exchange for one captive held by Ukrainian authorities on March 3, 2016.[136]

Recommendations

To The Government of Ukraine

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch call upon the Ukrainian government to:• Take immediate steps to end any and all enforced disappearances, including unacknowledged detentions for any period of time and irrespective of who is the detaining body;

• Investigate all allegations of enforced disappearances and bring those responsible for such crimes to justice through fair trials;

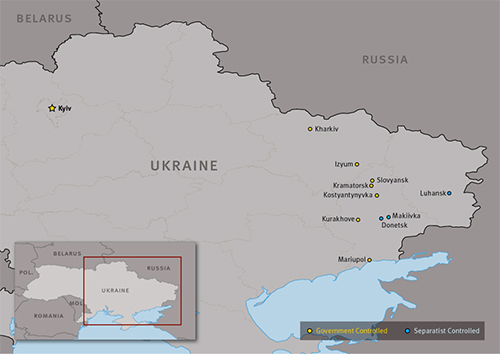

• Conduct immediate, effective and impartial investigations of the allegations of unacknowledged detention of individuals at the SBU facilities in Kharkov, Kramatorsk, Mariupol, and Izyum during the whole of the period since the beginning of the conflict in eastern Ukraine in April 2014;

• Take immediate steps to ensure that no individual held by any law enforcement and security agency and other official forces is subjected to torture or other ill-treatment;

• Undertake prompt, thorough and impartial investigations into all well-founded allegations of torture or other ill-treatment, report publicly on the findings of those investigations, and bring all those responsible for violations against detainees to justice through fair proceedings;

• Immediately end all practices of arbitrary detention, including detention by members of paramilitary forces and by members of any government agencies which do not have the authority to hold individuals in custody, detention of individuals outside of officially designated places of detention, and incommunicado detention;

• Investigate all credible allegations of arbitrary detention by forces and agencies under their control; identify and, where evidence permits, prosecute in conformity with international standards of fairness all those implicated in such practices, including law enforcement and military officials who condone, or are complicit in, such practice;

• Suspend officials implicated in any of the above unlawful practices, including commanding officers suspected of condoning or tolerating such practices; prevent these officials from having any further contact with detainees until investigations have been completed; where there is sufficient evidence that these officials have committed a crime under international law or other serious violation of human rights, prosecute them in conformity with fair trial standards;

• Immediately reveal, or promptly establish, the fate and whereabouts of all missing persons, and specifically those who have been allegedly taken into custody or otherwise forcibly disappeared by members of forces under the Ukrainian government’s control;

• Either charge any individual in the custody of the Ukrainian government with an internationally recognized crime, in which case give them immediate access to lawyers of their choice and inform their family accordingly, or immediately release them;

• Introduce and consistently enforce, with immediate effect, a policy of “zero tolerance” of torture throughout the criminal justice system;

• In all remand hearings and other court proceedings, when detainees are brought before a judge, ensure that members of the judiciary and prosecution and government officials are attentive to indications and allegations that prisoners have been subjected to torture or other ill-treatment; if signs of ill-treatment are observed or if such allegations are substantiated by other credible evidence, order prompt, thorough and impartial investigations;

• Ensure that all those involved in military and law-enforcement operations are made fully aware of the provisions of national and international law applicable to their actions and their potential personal and command responsibility for any breaches of these provisions;

• Fully cooperate with the relevant special procedures mechanisms of the UN, specifically the Special Rapporteur on Torture, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions, and the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; allow these special procedures mechanisms to undertake visits to Ukraine, issue invitations to their members, and provide access to both official places of detention and other places where unofficial detention of individuals has been alleged;

• Fully cooperate with the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (SPT), established under the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; in particular, host and facilitate a repeat visit by its delegates to Ukraine under guarantees of unhindered access to all detention facilities, including those that the subcommittee had been prevented from inspecting on their suspended visit in May 2016, in full conformity with Ukraine’s obligations under this instrument;

• Investigate the allegations of arbitrary detention of individuals for the purpose of “prisoner exchange”, and bring to justice the alleged perpetrators of such practice in proceedings that meet international standards of fairness.

To the Separatist ForcesAmnesty International and Human Rights Watch call upon the de facto authorities in the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics to:• Take immediate steps to ensure that no individual in their custody is subjected to torture or other ill-treatment;

• End the alleged practice of arbitrary detention of individuals for the purpose of “prisoner exchange”;

• Prohibit any form of arbitrary detention by members of forces under their control, including detention in secret locations and incommunicado detention;

• Investigate promptly, thoroughly and impartially all allegations of enforced disappearances and incommunicado detention, including in the facilities named in this report, and of torture or other ill-treatment by forces under their control, and ensure that suspected perpetrators are brought to justice through fair trials;

• Suspend persons suspected or accused of crimes involving individuals in their custody from their duties and prevent them from having further contact with detainees during investigations and any further proceedings;

• Ensure that all those involved in military and law enforcement operations are made fully aware of the provisions of international law applicable to their actions and their potential personal and command responsibility for any breaches of these provisions;

• Fully cooperate with the relevant special procedures mechanisms of the UN, specifically the Special Rapporteur on Torture, the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions, and the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances should they be willing to visit territory and all places of detention, as requested, under the control of the de facto authorities.

To the International Community

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch call on Ukraine’s international partners to:• Monitor and report on human rights abuses by both parties of the conflict in Ukraine;

• Raise findings and concerns with the Ukrainian authorities at every opportunity, in the relevant bi- and multilateral fora. Ensure that recommendations to all parties are reflected in relevant multilateral decisions and resolutions addressing human rights in Ukraine. In particular, insist on a “zero tolerance” policy with regard to enforced disappearances and incommunicado detention, as well as torture and other ill-treatment by members of military, security, and law enforcement agencies.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch call on the authorities of the Russian Federation to exercise their leverage over the de facto authorities in the DNR and LNR to ensure that disappearances, arbitrary and incommunicado detention, as well as torture and other ill-treatment practices, are stopped immediately and that all alleged perpetrators of such abuses are held accountable.

AcknowledgementsThis report was researched and written by Tanya Lokshina, senior researcher with Human Rights Watch’s Europe and Central Asia division, and a team of experts at Amnesty International.

The report was edited by Rachel Denber, deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia division, who also contributed to the analysis. Aisling Reidy, senior legal advisor, provided legal review and contributed to legal analysis, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director, provided program review. Amnesty International also reviewed the report and contributed to legal analysis.

Production assistance was provided by Anastasia Ovsyannikova, Kathryn Zehr and Anze Mocilnik, associates in the Europe and Central Asia division; and Christina Kovacs, coordinator in the Program Office. Layout and production were undertaken by Grace Choi, publications director; Olivia Hunter, photo and publications associate; and Fitzroy Hepkins, production manager.The cover illustration was designed by Brian Stauffer. The map was designed by John Emerson.

Human Rights Watch wishes to thank Amnesty International for cooperation on this very important project. We also wish to thank witnesses and other individuals who came forward and offered testimony and other information for this report.