Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine16 November 2015 to 15 February 2016

by Office of the United Nations, High Commissioner for Human Rights

ContentsI. Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 1–21 6

II. Rights to life, liberty, security and physical integrity .............................................. 22–67 10

A. Alleged violations of international humanitarian law ..................................... 22–31 10

B. Casualties ........................................................................................................ 32–37 12

C. Missing persons .............................................................................................. 38–44 14

D. Summary executions, enforced disappearances, unlawful and arbitrary

detention, and torture and ill-treatment ........................................................... 45–66 15

III. Accountability and administration of justice ........................................................... 67–107 21

A. Accountability for human rights violations and abuses in the east ................. 67–85 21

B. Individual cases .............................................................................................. 86–90 24

C. High-profile cases of violence related to riots and public disturbances .......... 92–107 26

IV. Fundamental freedoms ............................................................................................ 108–148 30

A. Violations of the right to freedom of movement ............................................. 108–118 30

B. Violations of the right to freedom of religion or belief ................................... 119–126 32

C. Violations of the right to freedom of peaceful assembly ................................ 127–132 33

D. Violations of the right to freedom of association ............................................ 133–139 34

E. Violations of the right to freedom of opinion and expression......................... 140–147 35

V. Economic and social rights ..................................................................................... 148–165 36

A. Right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health .......... 152–158 38

B. Housing, land and property rights ................................................................... 159–165 39

VI. Legal developments and institutional reforms......................................................... 166–182 40

A. Notification on derogation from the International Covenant on Civil

and Political Rights ......................................................................................... 166–167 40

B. Notification in relation to 16 United Nations treaties ..................................... 168–169 41

C. Constitutional reform ...................................................................................... 170–171 42

D. Implementation of the Human Rights Action Plan ......................................... 172–173 42

E. Adoption of the law on internally displaced persons ...................................... 174–175 42

F. Draft law on temporarily occupied territory ................................................... 176–178 43

G. Amendments to the criminal law .................................................................... 179 43

H. Reform of the civil service .............................................................................. 180 43

I. Civil registration ............................................................................................. 181–182 44

VII. Human Rights in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea .......................................... 183–200 44

A. Due process and fair trial rights ...................................................................... 188–190 45

B. Rights to life, liberty, security and physical integrity ..................................... 191 46

C. Violations of the right to freedom of opinion and expression......................... 192 46

D. Violations of the right to freedom of religion or belief ................................... 193–194 46

E. Right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health .......... 195 47

F. Discrimination in access to services ............................................................... 196 47

G. The ‘civil blockade’ of Crimea ....................................................................... 197–200 47

VIII. Conclusions and recommendations ......................................................................... 201–215 48

I. Executive Summary

I. Executive Summary1. This is the thirteenth report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on the situation of human rights in Ukraine, based on the work of the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU)1. It covers the period from 16 November 2015 to 15 February 20162.

2. During the reporting period, despite a reduction in hostilities, the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine continued to significantly affect people residing in the conflict zone and all their human rights. The Government of Ukraine continued to not have effective control over considerable parts of the border with the Russian Federation (in certain districts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions). Reportedly, this facilitated an inflow of ammunition, weaponry and fighters from the Russian Federation to the territories controlled by the armed groups.

3. The ceasefire in certain districts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions in eastern Ukraine agreed upon during the previous reporting period was further strengthened by the “regime of complete silence” introduced on 23 December 2015. However, in January and February, the Special Monitoring Mission of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) observed systematic violations of the ceasefire. During the same period, clashes and exchanges of fire have escalated in several flashpoints, predominantly near the cities of Donetsk and Horlivka (both controlled by the armed groups), and in small villages and towns located on the contact line, such as Kominternove (controlled by armed groups) and Shyrokyne and Zaitseve (divided between Ukrainian armed forces and armed groups).

4. While small arms and light weapons were most frequently employed during these incidents, the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission continued to report the presence of heavy weapons, tanks and artillery systems under 100mm calibre on either side of the contact line. Even if sporadic, the continued occurrences of indiscriminate shelling and the presence of anti-personnel mines and remnants of war exposed civilians to a constant threat of death or injury. During the reporting period, explosive remnants of war (ERW) and improvised explosive devices (IED) remained the main cause of civilian casualties in the conflict zone.

5. In addition, Ukrainian armed forces continue to position themselves near towns and villages while armed groups have embedded deeper into residential areas, further endangering the local population. The risk of re-escalation of hostilities therefore remained high.

6. The conflict continued to cause civilian casualties. Between 16 November 2015 and 15 February 2016, OHCHR recorded 78 conflict-related civilian casualties in eastern Ukraine: 21 killed (13 men and eight women), and 57 injured (41 men, eight women, six boys and two girls) – compared with 178 civilian casualties recorded (47 killed and 131 injured) during the previous reporting period of 16 August – 15 November 2015. Overall, the average monthly number of civilian casualties during the reporting period was among the lowest since the beginning of the conflict. In total, from the beginning of the conflict in mid-April 2014 to 15 February 2016, OHCHR recorded 30,211 casualties in eastern Ukraine, among civilians, Ukrainian armed forces, and members of armed groups – including 9,167 people killed and 21,044 injured.3

7. In the absence of massive artillery shelling of populated areas, ERW and IEDs remained the main cause of civilian casualties in the conflict zone during the reporting period. Given the threat that is presented by such weapons, there is an urgent need for extensive mine action activities, including the establishment of appropriate coordination mechanisms, mapping, mine risk education and awareness, on either side of the contact line.

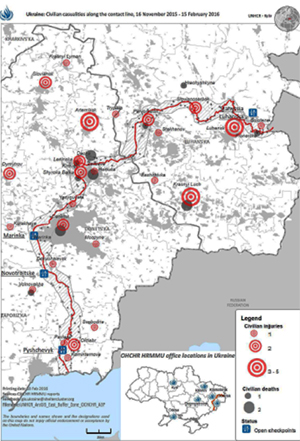

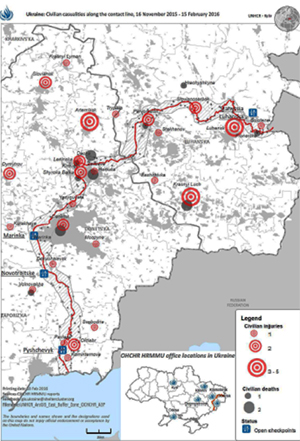

8. People living in the conflict-affected area shared with OHCHR that they feel abandoned, particularly in villages located in the ‘grey’ or ‘buffer’ zone (See Map of Ukraine: Civilian casualties along the contact line, 16 November 2015 – 15 February 2016)4. Often trapped between Government and armed group checkpoints, some of these areas, such as Kominternove, have been deprived of any effective administration for prolonged periods of time. Others are divided by opposing armed forces (such as Shyrokyne and Zaitseve), while some towns are located near frontline hotspots (such as Debaltseve and Horlivka). The contact line has physically, politically, socially and economically isolated civilians, impacting all of their human rights and complicating the prospect for peace and reconciliation. Over three million people live in the areas directly affected by the conflict5 and urgent attention must be paid to protect and support them. Their incremental isolation emboldens those who promote enmity and violence, and undermines the prospect for peace.

9. Some assistance to territories under armed group control is being provided by local humanitarian partners, bilateral donors, and reportedly the Russian Federation, which delivers convoys, without the full consent or inspection of Ukraine. However, this aid is insufficient to respond to all the needs of 2.7 million civilians living in territories under the control of armed groups, and particularly those 800,000 living close to the contact line, who are particularly vulnerable.

10. The Government has registered 1.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs), who have fled their homes as a result of the conflict. Between 800,000 and 1 million IDPs are living in territories controlled by the Government, where some continue to face discrimination in accessing public services. OHCHR has observed that some IDPs are returning to their homes, while others are unable to do so due to the destruction or military use of their property. According to government sources in neighbouring and European Union countries, over 1 million Ukrainians are seeking asylum or protection abroad, with the majority going to the Russian Federation and Belarus6.

11. According to the State Border Service, some 8,000 to 15,000 civilians cross the contact line on a daily basis, passing through six checkpoints in each transport corridor: three checkpoints operated by the Government, and three by the self-proclaimed ‘Donetsk people’s republic’7, with a stretch of no-man’s land in between. OHCHR has regularly observed up to 300-400 vehicles – cars, minivans and buses – waiting in rows on either side of the road. Passengers spend the night in freezing temperatures and without access to water ‘Donetsk people’s republic’, freedom of movement has been further restricted, aggravating the isolation of those living in the conflict-affected areas. Policy decisions by the Government of Ukraine have further reinforced the existing contact line barrier. Moreover, there remains an almost total absence of information regarding procedures at checkpoints, subjecting civilians to uncertainty and arbitrariness.

12. Residents of territories under the armed groups’ control are particularly vulnerable to human rights abuses, which are exacerbated by the absence of the rule of law and any real protection. OHCHR continued to receive and verify allegations of killings, arbitrary and incommunicado detention, torture and ill-treatment in the ‘Donetsk people’s republic’ and ‘Luhansk people’s republic’8. In these territories, armed groups have established parallel ‘administrative structures’ and have imposed a growing framework of ‘legislation’ which violate international law, as well as the Minsk Agreements.

13. The ‘Donetsk people’s republic’ and ‘Luhansk people’s republic’ continued to deny OHCHR access to places of detention. OHCHR is concerned about the situation of individuals deprived of their liberty in the territories controlled by armed groups, due to the complete absence of due process and redress mechanisms. Of particular concern are those currently held in the former Security Service building in Donetsk and in the buildings currently occupied by the ‘ministries of state security’ of the ‘Donetsk people’s republic’ and ‘Luhansk people’s republic’.

14. OHCHR is also increasingly concerned about the lack of space for civil society actors to operate and for people to exercise their rights to freedoms of expression, religion, peaceful assembly and association in the territories controlled by armed groups. In January 2016, the ‘ministry of state security’ carried out a wave of arrests and detention of civil society actors in the ‘Donetsk people’s republic’.

15. OHCHR documented allegations of enforced disappearances, arbitrary and incommunicado detention, and torture and ill-treatment, perpetrated with impunity by Ukrainian law enforcement officials, mainly by elements of the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU). OHCHR urges the Ukrainian authorities to ensure prompt and impartial investigation into each reported case of human rights violations, as well as the prosecution of perpetrators. Accountability is critical to bring justice for victims, curtail impunity, and foster long-lasting peace.

16. OHCHR was granted access to official pre-trial detention facilities throughout areas under Government control9 and, following some of its interventions, noted some improvements in conditions of detention and access to medical care for some detainees in pre-trial detention in Odesa, Kharkiv, Mariupol, Artemivsk and Zaporizhzhia. In some cases, OHCHR intervention also led to due attention being afforded to allegations of illtreatment and to law enforcement investigations into violations of other human rights in custody. These improvements confirm the importance for OHCHR to enjoy unfettered access to all places of detention.

17. OHCHR is concerned about the lack of action toward clarifying the fate of missing persons and preventing persons from going missing as a result of the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine. There should be a clear commitment at the highest levels of the Government of Ukraine and by the ‘Donetsk people’s republic’ and ‘Luhansk people’s republic’ to fully cooperate on missing persons cases. Mechanisms to clarify the fate of missing persons need to be effective, impartial and transparent, and the victims and their families should always be at the centre of any action.

18. OHCHR continued to monitor the investigations and proceedings into the killings that occurred during the 2014 Maidan events, the 2 May 2014 Odesa violence, the 9 May 2014 Mariupol incidents and the 31 August 2015 Kyiv violence. The lack of progress in these cases undermines public confidence in the criminal justice system. It is essential that they be promptly addressed with absolute impartiality as their mishandling can jeopardize the peaceful resolution of disputes and fuel instability.

19. During the reporting period, the Government of Ukraine took steps towards ensuring greater independence of the judiciary, adopted a plan of action for the implementation of the National Human Rights Strategy, and improved its legislation on internally displaced persons (IDPs). However, some critical measures remain to be adopted, including the much-awaited parliamentary vote on decentralization, which has been postponed and should take place by 22 July 2016. Envisioned as part of the Minsk Process, this vote is to be the precursor to a series of steps toward peace. Decentralization was conceived as part of a package of confidence-building measures. These measures included the immediate and full ceasefire; pull-out of all heavy weaponry by either side of the contact line; dialogue on the modalities of conducting local elections in accordance with Ukrainian legislation; pardon and amnesty through law; release and exchange of all hostages and illegally-held persons; safe access and delivery of humanitarian aid; modalities for the full restoration of social and economic connections; restoration of control of the state border by the Ukrainian government in the whole conflict zone; pull-out of all foreign armed formations, military equipment, and mercenaries; constitutional reform containing the element of decentralization and approval of the special status of particular districts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions10.

20. The Government of Ukraine extended the territorial scope of its intended derogation from certain provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) to territories it does not effectively control, as well as to areas it partially or fully controls in Donetsk and Luhansk regions. This may further undermine human rights protection for those affected.

21. Despite being denied access to the peninsula, OHCHR continued to closely follow the situation in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (“Crimea”)11, primarily relying on first-hand accounts. OHCHR, guided by the United Nations General Assembly resolution 68/262 on the territorial integrity of Ukraine remains concerned about violations taking place in Crimea, which is under the effective control of the Russian Federation. The imposition of the citizenship and the legislative framework of the Russian Federation, including penal laws, and the resulting administration of justice, has affected human rights in Crimea, especially for ethnic Ukrainians, minority groups, and indigenous peoples, such as Crimean Tatars. During the reporting period, OHCHR documented a continuing trend of criminal prosecution of Crimean Tatar demonstrators as well as arrests of Crimean Tatars for their alleged membership in ‘terrorist’ organizations. In a significant and worrying development, on 15 February, the prosecutor of Crimea filed a request with the supreme court of Crimea to recognize the Mejlis, the self-governing body of the Crimean Tatars, as an extremist organization and to ban its activities. Some decisions by the Government of Ukraine also affected the human rights of Crimeans, including those limiting their access to banking services in mainland Ukraine. The ‘civil blockade’ which Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian activists imposed as of 20 September 2015 – and which led to some human rights abuses – was lifted on 17 January 2016.

_______________

Notes:1 HRMMU was deployed on 14 March 2014 to monitor and report on the human rights situation throughout Ukraine and to propose recommendations to the Government and other actors to address human rights concerns. For more details, see paragraphs 7–8 of the report of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Ukraine of 19 September 2014 (A/HRC/27/75).

2 The report also provides an update of recent developments on cases that occurred during previous reporting periods.

3 This is a conservative estimate of OHCHR based on available data.

4 The 2016 UN Humanitarian Response Plan for Ukraine identifies the 0.8 million people living in areas along the contact line (200,000 in areas under Government control and 600,000 in areas under the control of the armed groups) as being in particular need of humanitarian assistance and protection.

5 This comprises 2.7 million in areas under the control of the armed groups and 200,000 near the contact line in areas under government control.

6 UNHCR, Ukraine Operational Update, 20 January – 9 February 2016.

7 Hereinafter ‘Donetsk people’s republic’.

8 Hereinafter ‘Luhansk people’s republic’.

9 In particular, in December 2015 and January 2016, HRMMU was granted unimpeded access to Mariupol SIZO and Artemivsk Penal Institution No. 6 of the State Penitentiary Service of Ukraine, where it could conduct confidential interviews with detainees. The administration and personnel of SIZO and the Penal Institution were transparent and constructive during these visits. The heads and medical personnel expressed commitment to improve medical care for detainees.

10 Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, 12 February 2015.

11 The Autonomous Republic of Crimea technically known as the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol.