CHAPTER XX

1873-1874

German University finances. Strassburg Professorship declined. Schliemann. Lectures on Darwin's Philosophy of Language. Emerson. Veddahs. Cromer. Lecture in Westminster Abbey. Order pour le Merita. Member of Hungarian Academy. Prince and Princess of Roumania. Oriental Congress. Last volume of Rig-veda. American attack on Max Muller.

The New Year found Max Muller quietly at Oxford, working at the last volume of the Veda, and at his Lectures on Religion, given in 1870, but never published, and preparing a short course of lectures for the British Institution on Language as the barrier between man and beast, which he called 'On Darwin's Philosophy of Language.' This was Prince Leopold's first year at Oxford as an undergraduate. Max Muller saw him constantly, and ever afterwards recalled their intercourse with genuine interest and affection, and he always hoped that the Prince might do much for his country as an enlightened patron of literature and art.

The following letter to Dr. Althaus refers to the dedication to Max Muller of Bulwer's Coming Race. The work was published anonymously, and it was only in the obituary notice in the Times that the secret of its authorship was disclosed.

Oxford, January 1, 1873.

'Many thanks for Bulwer. Only think, I never knew him, never even saw him, and learnt first after his death, who had written The Coming Race. One ought not to be proud of anything, but I was very much delighted.'

To R. B. D. Morier, Esq.

Oxford, January 1, 1873.

'My dear old Fellow,—Best wishes for the New Year. I don't know whether you see many English papers; old Stockmar has been reviewed in most of them, and it is very interesting to see how Johannes Bos has looked at him from different points. There was one review in the Morning Post more or less official, or Palmerstonian. It might be a good subject for an article in the Augsburger, or some other Zeitung, to show how the book has been received and partly digested in England. I have had several private letters which show that the book has told in various ways. I hope you observed Gladstone's civilities in his last Glasgow speech (before he came to Strauss). Do you know of anybody who could write such an article? Young Stockmar is not the man to do it; he is evidently put out by the critics, as if it was worth while writing a book to which everybody is to say Amen. Ever yours.'

To Canon, now Dean, Farrar.

January 6, 1873.

'Allow me to thank you at once for the copy of your Lectures on the Families of Speech, and for your very kind dedication. You say much more than I deserve, and all I can do is to do my best to deserve some part of your good opinion, by what I still hope to do for the Science of Language. At present my hands and my thoughts are full of other work. I am writing lectures on the "Science of Religion," and to know what to say and what not to say in four introductory lectures is no easy matter. In fact, I should gladly retire from my task, if I could, for I hardly feel up to work, and I am not satisfied with what I have written. As soon as I see a little daylight, and find leisure for other work, I shall read your lectures, and after I have done so I hope to write to you again, or, still better, have a talk with you on points on which we differ, and on points on which we agree. In the meantime accept my hearty thanks.'

Mr. Gladstone had addressed some inquiries to Max Muller on the constitution of German Universities, to which the following letter gives an answer:—

Parks End, January 12, 1873.

'I have no book at hand where I could find the exact sum allowed to each University by Government, but such books exist, and I have asked George Bunsen at Berlin to send me something like a Blue Book on the subject. The Universities derive their whole income from Government. Even in cases where there are ancient foundations still preserved, the funds or the land must be administered under the cognizance of Government, generally by a Government Commissioner. The only other source of income consists in the fees paid by the students. These in the case of the principal Professors, who lecture on Anatomy, Church History, or such like indispensable subjects, are considerable. Savigny, being Professor of Law at Berlin, declined the Ministry of Justice, unless his income as Minister could be raised to what his income was as Professor. A class of 400 students would yield a Professor during the two semesters 1,600 louis d'or, and some of the Professors in my time used to give two courses of lectures in each semester. The highest salary now paid to a Professor is only 4,000 thalers, or £600, yet even that is more than the average income of a Professor at Oxford, with the exception of the Theological Chairs. Considering the general income of the country, the sum expended by Government on the Universities is high. The number of Universities is large, each independent Prince wished to have a University, and I believe they will be kept up even now, for they have proved useful centres of intellectual life in every part of Germany. The difficulty to which you allude of teachers examining their own pupils is little felt. The Professor, lecturing to a large class, does not know many of the students personally. The examination is always conducted by a Commission consisting of five or six Professors. Besides, the University degree does not confer any tangible rights. In order to become a lawyer, a clergyman, a physician, a schoolmaster, every candidate has to pass the Government Examination, and with these the Professors, qua Professors, have nothing to do. It was to me a matter of great interest to compare the working of a German University, such as Strassburg, with what I knew of Oxford. Each country, no doubt, fashions its own Universities, and makes them to supply the real wants of the people. Yet there is much to be learnt from a comparison of the two systems. I shall be very glad to undergo a cross-examination when you are in London again. I believe the time will come when something will have to be done, not only for Ireland, but for England too. Oxford wants new life. Both teaching and learning seem to me to be regarded as a burden, which ought not to be. I send you a few papers which may partly answer your purpose. In the little calendar you will find the statistics of the German Universities, as far as their teaching staff and the number of students are concerned. In the plan of the lectures you see what is done even by so small a University as Strassburg. You can see how almost every Professor has a laboratory, seminary, hospital, or institution, supported by assistants, where he works with his pupils apart from his lectures. These institutions are the real secret of the success achieved by the German Universities. In several cases the students who are admitted to them receive, while they are at work, an exhibition or fellowship. Anyhow, these institutions are the real workshop where the tradition is handed down from generation to generation. The Colleges with their fellowships might be made to answer some such purpose. There are many Professors in Germany who would have spoken like Dollinger on Materialism. What I like in the German Universities is the frankness with which everybody states the convictions at which he has arrived. Strauss's book has been very severely treated in Germany. Yet there is a crisis going on there as in England; something is dying, whether we like it or not. To my mind Mansel's Bampton Lectures and the reception they met with were a sign of the times. They seemed to me far more irreligious than Herbert Spencer. They left religion as a mere cry of despair. Frederick Maurice saw the tendency of that school of thought which erects an insurmountable barrier between the finite mind and the infinite, but he could not make himself understood. Mansel and Herbert Spencer seem to me at the present moment to rule at Oxford in the two opposite camps, and I do not wonder that they produce in each much the same results. I spent some interesting hours with Dollinger at Munich. He is a man of great courage in thought and word; but, though he is a strong and vigorous old man, he shrinks from action. He is Erasmus over again; a rougher nature will be wanted to do the rougher work.'

To His Mother.

Translation. Oxford, January 18, 1873.

'Stockmar is selling well. The Queen has thanked me in the kindest manner for the preface. Prince Christian wrote at the Queen's desire, and she expressed herself kindly about the book altogether. ... I had almost forgotten the Emperor (Napoleon). Let him rest in peace. One must not judge him, but few men have caused so much misery in the world as he. He was always liked in England, so his death has called out a good deal of sympathy. The last years of his life must have been a hard penance.'

To The Same.

Translation. February 16.

'The Strassburg uncertainty is over. I wrote them word that with all my private work I could only lecture one term in the year, and on account of the other Professors they could not arrange that. I am glad, for I had done my duty, and should have had to make a great pecuniary sacrifice, and it would have taken up too much of my time, and I could not with a good conscience have undertaken more than I offered. My chief thought has been about the children, and whether it would not be better for them to be brought up in Germany. That is often a weight on me, for the arrangements here are very imperfect. One can manage for the girls, but how it will be for Wilhelm, I do not yet see. But time will show. As yet he learns nothing, but is healthy and merry. G. is not very unhappy about Strassburg.'

To Dean Stanley.

Oxford, February 21, 1873.

'I now have lectures in London and Birmingham. As soon as these are over the printing of Volume VI [of the Rig-veda] will begin, and then I shall go on with the translation. I found my work so in arrears, that for the present, at least, I have given up a change to Strassburg. I am very sorry, for the life in Strassburg was like a mental sea-bath. I wrote last week to give it up.'

To His Mother.

Translation. Oxford, February 25.

'Yesterday I dined with Prince Leopold, and he said the Queen had charged him to tell me how pleased she was that I had decided to stay in England. I am writing to Strassburg to found a Stipendium in their University with the 2,000 thalers they paid me last year, for the study of the Veda. It will not hurt me, and I am glad not to take any money from them. The people in Strassburg and Berlin have been very friendly over the whole matter; even Bismarck expressed his sorrow at my decision.'

And thus the uncertainty about Strassburg which had hung over the family for above a year came to an end. The Prize founded by Max Muller, and which bears his name, is given every third year for the best dissertation on 'Vedic Literature,' and may be competed for not merely by present students at Strassburg, but by those who have already taken their degree, provided they studied for at least four terms at that University.

It was in this year that Max Muller made the acquaintance of Dr. Schliemann, the famous excavator, at first by correspondence only. From the first, Max Muller took a great interest in Dr. Schliemann's work; the disinterested character of the discoverer appealed to him, though he often found himself unable to follow Dr. Schliemann's deductions, and to the last he used smilingly to say, 'He destroyed Troy for the last time.' In 1875 Dr. Schliemann paid a visit to Oxford, and stayed with Max Muller, who for several years was instrumental in getting Schliemann's papers and articles inserted in the leading newspapers and periodicals. When Dr. Schliemann exhibited his Trojan treasures at the South Kensington Museum, Max Muller spent some time in London helping him to arrange the things—an arduous task, for, as is well known, though he had the scent of a truffle dog for hidden treasures, he had little or no correct archaeological knowledge, and Max Muller found the things from the four different strata which Schliemann considered he had discovered at Troy in wild confusion—though he maintained they were all carefully packed in different cases. One day when Max Muller was busy over a case of the lowest stratum, he found a piece of pottery from the highest. 'Que voulez-vous? [Google translate: What do you want?]' said Schliemann, 'it has tumbled down!' Not long after, in a box of the highest stratum appeared a piece of the rough pottery from the lowest, 'Que voulez-vous?' said the imperturbable Doctor, 'it has tumbled up!' The friends met again at Maloja in 1885, Dr. Schliemann had meantime finished his beautiful house in Athens, in which two bedrooms were called after Max Muller, and many were the pressing invitations to occupy them; but when Max Muller visited Athens in 1893, his kind friend had passed away. He gave Max Muller a good many things from Mycenae, which are now in the Ashmolean Museum, and also a tiny bit of gold from Agamemnon's grave. The correspondence is of too technical a character to be given here; interesting letters from Max Muller on Athene Glaucopis and Hera Boopis, on the Hindu Svastika, and on Jade tools are inserted in Schliemann's Troja. Dr, Schliemann also gave Max Muller the valuable Tanagra figures, which his friends will remember in the drawing-room at 7, Norham Gardens.

Max Muller's American friend Mr. Conway was at this time preparing an Anthology culled from the religious books of different sects and beliefs. Hence the following letter. In the sentiments of the latter part most people will agree.

To Moncure D. Conway, Esq.

Parks End, March 13, 1873.

'I can see no objection to your printing a number of verses from the Dhammapada, but as the book is not my own, 1 think it would be better if you communicated with the publisher, Mr. Trubner. As to lectures, I am at present so overworked that I ought not to make new engagements. I shall have to give three lectures at the Royal Institution, then at Birmingham, and I have my Oxford lectures going on at the same time, so that this is as much as I can safely do. Lastly, a Mythological Society sounds a somewhat ominous name; yet I quite agree with you that it might do good. However, what I should like to see would be a concentration of the different Societies, and the constitution of a London Academy, divided into Sections. So much work and money are now frittered away, and the Transactions and Journals of the numerous Societies have become mere burial-grounds; for who can even cut open their pages? I read with great interest the Index, where I occasionally see your name. Does that paper tell in America? and what is or are the really powerful organs of thought in the United States?'

The end of March the three lectures on Mr. Darwin's Philosophy of Language were given at the Royal Institution. They were printed in Frasers Magazine, and also a very few copies for presentation, but were never republished in a collected form.

The following letter alludes to the completion this spring of Mr. Bellows' excellent pocket French Dictionary, a copy of which Max Muller always took about with him, and he invariably recommended it as the best type of dictionary he knew in any language:—

To Mr. Bellows.

Parks End, April 2, 1873.

'My dear Friend,—Many thanks for your charming Dictionary, which I found here on my return from London. I am too busy just now to do more than admire it, and congratulate you on its successful termination. I know no other pocket Dictionary that could compete with it. Your discoveries at Gloucester are very curious [Roman wall in his own garden], and I hope I shall be able to inspect them some day or other. Just now I am lecturing in London on "Language as the Barrier between Man and Beast," and I have hardly any thought for anything else. In a few weeks I hope I shall be more free again.'

The next letter refers to an interesting article written by Dr. Althaus in one of the magazines on 'The Germans in England,' Max Muller's is the last name in the article.

To Dr. Althaus.

Translation. Oxford, April 13.

'My dear Doctor,—I do not know how to thank you. I have just read your essay, and indeed I feel it would be superhuman if, after reading what you say, I did not feel as in a sort of champagne mood. I, of course, know best how much too much you have said of me, but even reducing it by half, there remains so much appreciation which I highly value. I have spent many happy and beautiful years in England, and even the little disappointments do not disturb me, and they cannot blur memory's sunny pictures. The only things I long for are my old friends. One feels more and more alone and solitary, and that feeling draws me so often towards Germany with a great longing. I do not know whether you feel the same. When I was young I did not know what Heimweh meant; now it increases with every new year.'

It was after the lectures in London that Emerson, who was paying his third and last visit to England, came to Oxford with his daughter as Max Muller's honoured guest. Max was one of Emerson's ardent admirers, and had known and loved his writings from his earliest days in England. On the second day of Mr. Emerson's visit. Prince Leopold lunched at 'Parks End' to meet the old man. It was a brilliant May day, and the whole party sat out in the garden after luncheon, and the hours slipped past in pleasant converse, till Prince Leopold proposed an adjournment to his house, which was near at hand, for five o'clock tea, when he delighted Mr. Emerson by showing him many private photographs of the rooms at Windsor, Osborne, and Balmoral. The next day, after attending Mr. Ruskin's lecture, the Max Mullers and Emersons visited him in his rooms at Corpus, where the scene recorded in Auld Lang Syne took place. Mr. Ruskin wrote afterwards to Max Muller to account for it, by saying, 'It chanced that both you and Mr. Emerson happened to say things from which I deeply and entirely dissented, and which reduced me at once to silence.'

To Charles Darwin, Esq.

Parks End, Oxford, June 29, 1873.

'Sir,—In taking the liberty of forwarding to you a copy of my Lectures, I feel certain that you will accept my remarks as what they were intended to be—an open statement of the difficulties which a student of language feels when called upon to explain the languages of man, such as he finds them, as the possible development of what has been called the language of animals. The interjectional and mimetic theories of the origin of language are no doubt very attractive and plausible, but if they were more than that, one at least of the great authorities in the science of language—Humboldt, Bopp, Grimm, Burnouf, Curtius, Schleicher, &c.—would have adopted them. However, it matters very little who is right and who is wrong; but it matters a great deal what is right and what is wrong, and as an honest, though it may be unsuccessful, attempt at finding out what is true with regard to the conditions under which human language is possible, I venture to send you my three Lectures, trusting that, though I differ from some of your conclusions, you will believe me to be one of your diligent readers and sincere admirers.'

That the Lectures did not alter Mr. Darwin's cordial appreciation of Max Muller is shown by the following charming letter, inserted by permission:—

Down, Beckenham, Kent, July 3, 1873.

'Dear Sir,—I am much obliged for your kind note and present of your Lectures. I am extremely glad to have received them from you, and I had intended ordering them. I feel quite sure from what I have read in your works that you would never say anything of an honest adversary to which he would have any just right to object; and as for myself, you have often spoken highly of me, perhaps more highly than I deserve.

'As far as language is concerned, I am not worthy to be your adversary, as I know extremely little about it, and that little learnt from very few books. I should have been glad to have avoided the whole subject, but was compelled to take it up as well as I could. He who is fully convinced, as I am, that man is descended from some lower animal, is almost forced to believe a priori that articulate language has been developed from inarticulate cries; and he is therefore hardly a fair judge of the arguments opposed to this belief.

'With cordial respect, I remain, dear Sir,

'Yours very faithfully,

'Charles Darwin.'

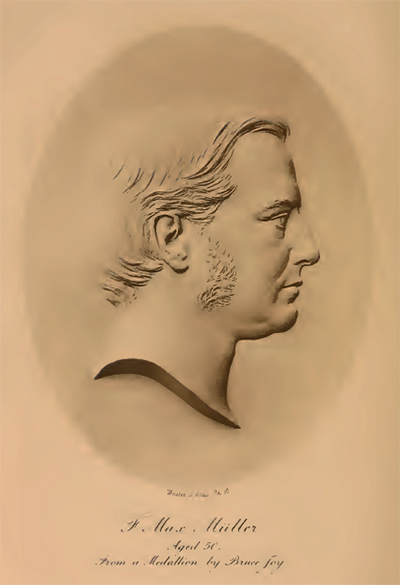

F. Max Muller, Aged 50. From a Medalliion by Bruce Foy

The Lectures were answered by Mr. Darwin's son, whose article was again replied to by Max Muller in the Contemporary Review, called, 'My reply to Mr. Darwin,' which in its turn provoked the violent attack by Professor Whitney on Max Muller described in the next chapter.

During this summer Max Muller sat to Mr. Bruce Joy for a medallion, and later on for a bust, in the habit brode [Google translate: He lives in Brode] of the French Institute, the clever artist being his guest whilst the work was carried out. Several pleasant and refreshing visits were paid to the Deanery, Westminster, which Lady Augusta Stanley made a second home to many of her husband's old Oxford friends. The Max Mullers also stayed at Sir William Siemens', for the Civil Engineers' soiree at the South Kensington Museum, an evening long remembered with pleasure, as spent almost entirely with Charles Kingsley looking at the Vernon collection of pictures, which at that time still hung there.

In July Max Muller went to Germany to bring his mother to England. She had been far from well for some months, and he found her at first unwilling to travel, and thus was kept longer in Germany than he expected.

To His Wife.

July, 1873.

'If we do a thing because we think it is our duty, we generally fail; that is the old law which makes slaves of us. The real spring of our life and our work in life must be love—true, deep love—not love of this or that person, or for this or that reason, but deep human love, devotion of soul to soul, love of God realized where alone it can be, in love of those whom He loves. Everything else is weak, and passes away; that love alone supports us, makes life tolerable, binds the present together with the past and future, and is, we may trust, imperishable.'

Whilst at Chemnitz with his mother, Max Muller wrote to tell Professor Benfey that his Index Verborum [Google translate: List of Words] of the Rig-veda was printed. He had prepared it himself before he brought out his first volume of the Rig-veda in 1849, and had lately employed a young German to arrange the Index for each one of the six volumes as a whole. It is still of great practical value, as, the references being to hymns and verses and lines, and not to pages, it can be used with any edition of the Rig-veda. He also mentions that a new edition of his Hitopadesa was called for, and of his Sanskrit Grammar in English, 'and yet,' he says, 'I have my hands already quite full.'

The Lectures on the Science of Religion, given in 1870, had been published just before Max Muller went to Germany, and were dedicated to Emerson, 'in memory of his visit to Oxford, and in acknowledgement of constant refreshment of head and heart derived from his writings during the last twenty-five years.'

The volume was favourably received, and called out less adverse criticism than it would have done three years before.

'Professor Max Muller,' says one reviewer, 'properly calls the lectures in this volume "An Introduction." They break ground in the little-trodden path of Comparative Theology. He tells us he is convinced that study here will ultimately produce as great a revolution in our ideas of man's past history, and in the relations and character of the various religions of mankind, as study of natural science has produced in our view of the Creation. Researches in the sphere of history, with the help of Comparative Mythology, prove that there are elements in human nature which must have been primal and original, which could never have been developed, which must have been implanted from the beginning—wherever we place that. That man, as a religious being, possesses such an element or disposition, we conceive Mr. Muller himself has gone far to prove. And the more we find, by comparison of the religions of the world, the distinctness and indestructibility, and yet the essential identity of this element under all varieties of forms of development, the more shall we be compelled to accept the fact of the Divine origin of mankind, and, even amid its worst corruptions, of the community of human nature with the Divine, of the finite with the Infinite.'

So little is still known about the Veddahs, that the following letter to Mr. Hartshorne may be of interest:—

Oxford, July 27, 1873.

'Dear Sir,—I have just returned from Germany, and I am afraid that my answer to your letter of June 23 will hardly reach you in time, before you start again on a new visit to the Veddahs. So much has been said about their peculiarities in language, thought, and manners, that a really trustworthy account of them would certainly be most valuable. How difficult such an account is you must know best by this time. In looking at your list of Veddah words I was struck at once by their Pali, i.e. secondary Sanskrit character. The question therefore, arises, are those Pali or Sinhalese words later importations, or is it possible to distinguish between an earlier substratum of Veddah speech and these clearly Aryan words? Or, does the Veddah language take its place simply as a degraded Sinhalese dialect, and the Veddah people as a degraded Sinhalese race, instead of being, as generally supposed, a remnant of a primitive and savage race? This question can be solved scientifically by linguistic evidence only. But the solution is most difficult. We must know what corruptions are possible between Veddah and Sinhalese, between Sinhalese and Elu, between Elu and Pali, between Pali and Sanskrit. ... I have marked on your list of Veddah words many that are clearly of Sinhalese kinship, and these are words which constitute the most necessary portion of a language; for instance, iht pronouns, words for man, cow, flowers, to cook, to go, &c. &c. Here and there I see a trace of grammatical structure, and you may be certain that there is as much grammar in the Veddah language as in English. You may say, that would not be much, but it presupposes much. No doubt it would be difficult to get an idea of English grammar from a Welsh coal-miner, and your Veddahs have evidently sunk much lower; but with great perseverance something of the grammatical articulation of the language might still be discovered, and has to be discovered, before we can say anything about their origin. 1 never believe that the Veddah language has no word for two. There may be Veddahs who do not count, or who, as philosophers would say, form no syntheses, but that a language which has a word for I and thou, for eye and ear, should have no sign for the dual concept, I shall never believe. More difficult even than the grammar is the religion of a people like the Veddahs. One occasionally sees accounts in the papers of a witness being sworn in an English Court of Law, and if one took his answers about the Deity, about life and death, and right and wrong, as materials on which to build a theory of the Christian religion, one would still be better off, I suppose, than with the best of the Veddahs. And yet these people have a religion, if one only knows how to disinter it. To call "the propitiation of the spirits of deceased ancestors" the most original form of religion is utterly wrong. It takes thousands of years before we arrive at such ideas. The idea of an ancestor involves the idea of relationship; a belief in deceased, but not yet extinct, ancestors implies the germs of a belief in immortality. The idea of a spirit, or of spirits of deceased persons, belongs to the tertiary age of thought, and as to propitiation, that is a concept not yet 3,000 years old. The time has not come yet for a chronology of religious beliefs; what we want are accurate statements of all manifestations which imply a conception of anything beyond what is given to man by his sensuous experience. All this is a work of very great difficulty, and it is because people do not see the difficulty, that we get so much material which is amusing and may fill volumes about Prehistoric Culture, and yet leaves us exactly where we were before. It is difficult when we have to deal with one individual, to say what he is no more, and what he is not yet; to say the same of a family, a clan, a tribe, a people, is much more difficult. And yet this is what we want to know about the Veddahs, whom many people are so anxious to represent as monkeys and not yet men, but who may be monkeys and men no longer.

'Excuse haste, and believe me,

'Yours very truly,

'F. M. M.'

After Max Muller's return to England with his mother, the whole family went to Cromer, which proved a time of great interest to him, as bringing him into closer contact with many members of the Gurney and Buxton families, with some of whom he had been associated years before through the marriages of his friends Ernest and George von Bunsen. On his return home he devoted himself to work on the sixth and last volume of the Rig-veda. He had during this year published the text of the Rig-veda in two small octavo volumes, according to the Pada and Samhita systems.

But his mind was ere long turned to another subject. His friend Dean Stanley had asked him the year before to give the evening address in Westminster Abbey on Christian Missions. Max Muller had then declined, but the Dean again urged his request this year. It was a bold step on the Dean's part, who had, however, ascertained that it was perfectly legal. He took the opinion on this point of Lord Coleridge, the Lord Chief Justice of England, who replied, 'It is perfectly legal, but whether it is expedient!' 'I did not ask your opinion on that point,' rejoined the intrepid little Dean. It needed no small courage in Max Muller to accept; but having ascertained from the Dean that it was legal, he now no longer hesitated, feeling it would put him in a position to say things that had long weighed on him. Having once made up his mind, he was perfectly unmoved by the storm it raised, and set about preparing his discourse with his usual tranquil self-possession and power of detaching himself from public opinion.

To R. B. D. Morier, Esq.

November 3.

'My dear Morier,—We had our orgie at All Souls last night, and I thought of you when I was presiding as Sub-Warden (the Warden being ill), supported by two noble lords, Lord Devon and Lord Bathurst, and proposing the different healths of the evening. I also thought of Bellum's and all that. Don't you think it is time for me to leave, having reached this exalted pinnacle?'

On December 2 the Max Mullers went to the Deanery at Westminster, and the next day the Lay Sermon was delivered. Charles Kingsley, Theodore Walrond, and Sir Charles Trevelyan dined and attended the service. It was very nervous work, both for the lecturer and many of his hearers, but his voice was clear and carried far, and his earnest, reverent manner impressed the vast congregation from the first moment. To one who for long years had wished that he could have an opportunity of uttering the great truths which were the foundation of his own life, other than that afforded by the Royal Institution, it was a unique moment, and a glance at his quiet, self-possessed face, showed that he was equal to the great task, and stilled all feeling of anxiety.

The next day both the congratulations and vituperations began; the latter made little impression. On his way home Max Muller met Dr. Liddon, who wrung his hand, saying, 'I rejoice from my heart that you have been helping us.' The author of The Childhood of Religion wrote:—

'I must thank you for your noble words in the Abbey last week, to which it was my delight to listen. I am sure they will do great good in directing attention to the place each faith has had in the order of this divinely-governed world.'

To The Dean of Westminster.

Parks End, Oxford, December 11, 1873.

'My dear Stanley,—So the work is done. I hope it may produce some good effect! I may tell you now that I never felt so nervous in my life before, but I had perfect confidence in you, that you would not have asked me unless you felt it ought to be done, and could be done. All the people I see here seem to acquiesce, but of course I have no opportunity of hearing their real opinion. Ruskin was truly pleased, and I believe would like to lecture himself. I wish the University Sermons could be opened to laymen—there seems to be no reason why they should not. Are you aware that in the Greek Church it is by no means unusual for laymen to occupy the pulpit? I read your sermon to-day—I had hardly heard it in the Abbey, I felt so excited. I like it very much. Did you see the new ending to my lecture? I felt there was something wanting to make the ending less abrupt, and as I am not likely to have another opportunity soon, I thought I might as well say all I had to say. Ever yours.

'I am truly grateful now that you asked me, and glad that I did it.'

To Professor Klaus Groth.

Translation. Oxford, December 14, 1873.

' My dear Friend,—It is long since I wrote. You have no idea how m time goes, and the letters I like to write have to wait for those I must write. I have written to Prince Christian about the Platt- Deutsch Bible: the thing can be done, and I have told him not to consult any one further, but to leave the arrangements entirely to you. One could begin with the New Testament—wait how that succeeds, before the Old Testament is undertaken. Yes, how much has happened again this year, and how little really effected! All has gone well with us. I am often frightened at our happiness. Wife and children well, my mother on a visit to us for the last six months, also far stronger than one dare expect. I certainly was laid up in summer, but am now quite well. I have said farewell to Strassburg with a heavy heart, but I hope wisely. It was not quite what I expected. There was a want of go, of initiative. My idea was that the best powers of Germany would come to this new Byzantium of literature, the Crown Prince at their head, that the Alsatians might be forced to be proud of their country, and that a new mental capital would be founded in Strassburg, as a make-weight to the military metropolis; but the reality, pleasant as it was, was different. Fritz Kraus1 [A young Swiss, who made an excellent translation of Shakespeare's Sonnets into German. He was a great invalid, and died of decline in 1881] has thanked vie for a notice you wrote on his Southampton Sonnets. Greetings to all our Kiel friends. ... I hope your Christmas will be one of undisturbed happiness. Your boys must be growing fast. Shall we soon meet? It does not look like it.'

To W. Longman, Esq.

Oxford, December 15.

'"Why is there so much delay about bringing out the Sermons?" the Dean writes to me from Windsor; but it is not my fault. I ordered my part for press on Wednesday. I look forward to three months' imprisonment with great pleasure. What an amount of work I shall be able to get through, having no dinner-parties, calls, meetings, &c., to interrupt my work!'

Some of the papers had threatened Max Muller with imprisonment for brawling in church, and an Oxford tradesman who had heard of this ran out of his shop one day as he was passing, and, seizing his hand, said, 'Well, sir, when they send you to prison, count on a hot dinner from my table every week.'