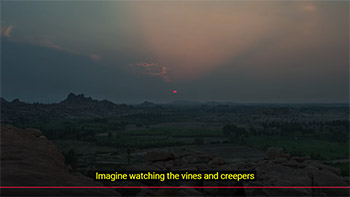

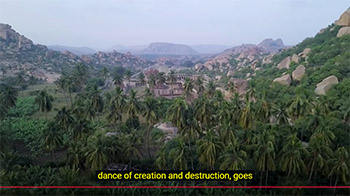

Plant life would have gradually crept in to reclaim the empty streets.

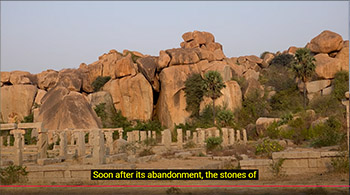

Soon after its abandonment, the stones of Vijayanagara would have sprouted with grasses. Banana and coconut palms would have begun to spring up in the streets

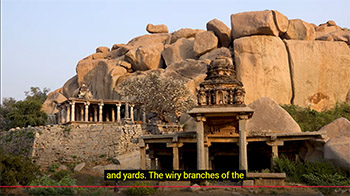

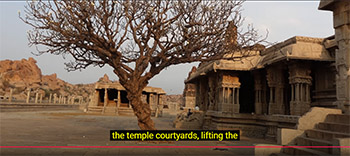

and yards. The wiry branches of the frangipani tree would burst up through

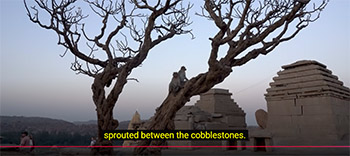

the temple courtyards, lifting the flagstones with their roots, while perennial weeds like the lion's ear and prickly pears would have

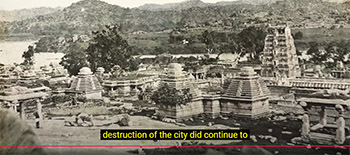

sprouted between the cobblestones. The kings of Vijayanagara who fled the

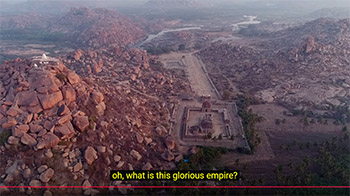

destruction of the city did continue to rule in a much diminished form for several more decades, and shifted their courts to their remaining territories in southern Andhra. In their grandeur and ceremony, their

processions and festivals, they attempted to recreate the splendor of their past, but in reality, they would never again

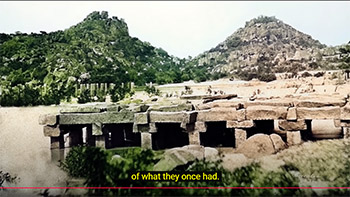

wield power in the same way. The glorious days of the great capital were now a distant memory. Like their great rivals the Delhi Sultanate and Bahmani Sultanate before them, they now ruled over a tiny portion

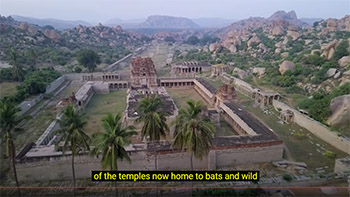

of what they once had. By the dawn of the 17th century, that power, too, evaporated, and the last of Vijayanagara's Nayaka lords went their separate ways. With the economic heart ripped out of the empire, without the booming economy of the temples and the markets of the

great metropolis, the surrounding towns and villages also went into decline. Port towns far away on the western coast like Bhatkal and on the eastern coast like Pulicat also shrunk around this time.

The dance of Shiva went on, and another great empire had passed into ruins. The historian Manu Pillai describes this time. The lessons for the sultans in the northern Deccan from this episode should have been clear; it was the inability of the Deccan's

ancient rulers, the Kakatiyas, Hoysalas, and Yadavas, to join together against their common enemy that led to the fall of their order at the hands of the Khiljis and Tughlaqs.

When the Bahmani Sultanate emerged, its leaders too ultimately failed to reign in dissension, and in only a few generations, the kingdom was on its way to decline and disintegration. The rebel sultans who seceded from the Bahmanis continued this tradition by constantly feuding with one another, but

Ramaraya's ambition reminded them at last that in the game they were playing, they were all destined to suffer as losers.

Together then, they rose against Ramaraya and demolished Vijayanagar for once and forever, achieving in a stroke something that even they perhaps could not have believed was entirely possible.

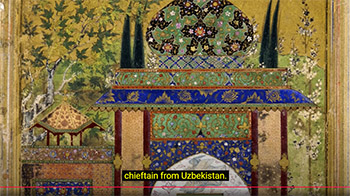

In the following years, in the north of India, a new power would rise in Delhi, founded by a warrior

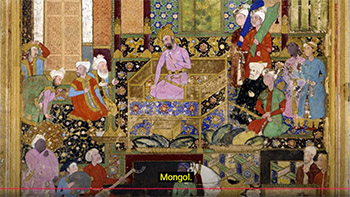

chieftain from Uzbekistan. He was Turco-Mongolian in ethnicity, and today we know the dynasty he founded by a name derived from the Persian word for

Mongol.

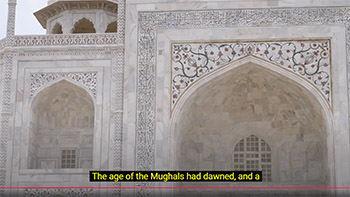

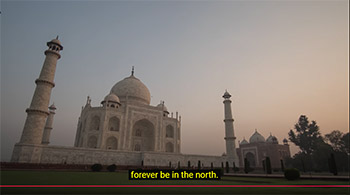

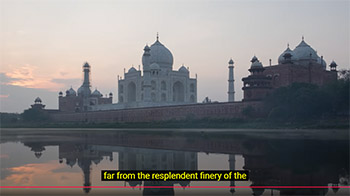

The age of the Mughals had dawned, and a new, glorious stage of Indian history would now begin. But the center of Indian power would now

forever be in the north. Around the same time, another much more underwhelming event would take place,

far from the resplendent finery of the Mughal court that would have perhaps an even greater impact on the history of this land.

In the year 1626, little more than 60 years after the battle of Talikota, the

British East India Company built its first fortified port near the coastal

town of Pulicat. This town was once the gateway by sea to the Vijayanagara Empire, and through here,

the empire had traded with Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and China. But in the decades since, the port town had fallen on hard times.