by Fred Pearce

New Scientist

September 29, 1983

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

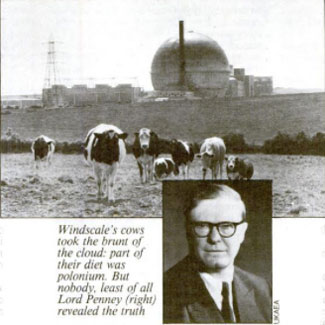

Windscale's cows took the brunt of the cloud: part of their diet was polonium. But nobody, least of all Lord Penney (right) revealed the truth

Britain's nuclear chiefs have kept secret for 26 years the truth about the extent of the release of radioactivity during a fire at the Windscale nuclear complex in 1957 -- until now. They did so, apparently, to preserve a military secret from their ally, the U.S.

Only a chance observation by a librarian at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne flushed out the admission that large quantities of the deadly isotope polonium-210 were released. His researches, published in New Scientist earlier this year (vol 97, p. 867), have forced the publication of classified reports on the make-up of the radioactive cloud that was released during the fire. The contents of those papers are revealed for the first time this week in a new report on the fire, published by the National Radiological Protection Board (NRPB)*.

But uncertainty still hangs over how many people died as a result of fallout from the cloud as it spread across Britain and on into Europe in October 1957?

The fire at Windscale's No. 1 pile remains the most serious accident in the nuclear industry of the West. The radioactivity was probably responsible for the deaths of dozens of people. The fire engulfed the pile, where uranium was being converted to plutonium for the British atomic bomb. But other materials were also secretly being produced in "loops" around the pile.

The official reports on the fire at the time said that by far the most important radioactive isotope released in the fire was iodine-131, produced in the core of the pile. But they made no mention of the fire reaching the loops or of anything in those loops escaping.

Now, the NRPB report reveals that "a number of sealed cartridges undergoing irradiation ... leaked in the course of the fire." The most important of these contained polonium-210, which was being produced by the irradiation of bismuth. Polonium was, at that time, a vital component of the British bomb, which was at that time undergoing tests at Christmas Island in the Pacific Ocean.

Scientists at Windscale knew from the beginning that large quantities of polonium were released during the fire. The isotope was found on filters at the top of the pile's chimney and at another filter nearby at Calder Hall. Several of the scientists recorded their findings in reports. But each of those reports was given the official stamp of secrecy and their publication stopped, until their "declassification" in recent weeks.

The official inquiries knew of the large polonium release. But the published version of the reports by Sir Alexander Fleck and Lord Penney, make no mention of polonium. Why the secrecy? Polonium was a vital component of the British bomb. It is highly radioactive and unstable and served, at that time, as the initiator, in the heart of the bomb by setting the whole chain reaction in progress. In the 1940s, when British scientists, including Penney, worked at Los Alamos in the U.S. to help make the first atomic bomb, its properties and chemistry were so secret that, according to Professor Margaret Gowing in the official history of the British nuclear industry: "This was one area of the Los Alamos work about which the British knew nothing."

Ten years later, the Americans had probably developed alternatives to polonium. But Britain had not.

One highly placed source in the nuclear business today told New Scientist that "Britain just did not want the Americans to know how we were making our bombs."

Certainly, the fact that Britain used the Windscale pile to produce polonium was kept a closely guarded secret, and was revealed only in Gowing's official history, published in 1974. Even in 1981, when a scientist from the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority, A.C. Chamberlain, reviewed the makeup of the Windscale cloud, his report went on the "secret" list.

Ironically, the only official paper published in the aftermath of the fire which so much as mentioned polonium was written by the man who is now the head of the NRPB, John Dunster.

In an obscure paper on the environmental effects of the fire, which was presented to a scientific session at the U.N. but never published in Britain, Dunster included in a list of substances released in the fire polonium-210. But he gave no figure for the amount released nor did he explain how it came to have been released.

One further question remains: how deadly were the 240 curies of polonium that the NRPB now estimates were released? Here the Dunster paper creates a second embarrassment for the NRPB. One table presented by Dunster, but again not commented on, reveals that, while sampling milk from cows near Windscale, Dunster and his colleagues found an average of 5 nanocuries of alpha-emitting particles per litre. This would, it turns out, have been almost entirely polonium. As the NRPB report now points out, apparently for the first time, this is an extraordinarily high figure which should have set alarm bells ringing. Today, however, the NRPB dismisses the result. There were "inconsistencies" in the research and the result is "very much higher than could be reasonably expected," given the amount of polonium on the grass. But this, in turn, raises doubts about the NRPB's method of calculating the amount of polonium that passes into a cow's milk or meat.

The NRPB now dismisses a model used in its own assessment of the effect of polonium emissions from coal-fired power stations. When John Urquhart, the Newcastle librarian, used the model in his own calculations, he came up with a figure that suggested that up to 1,000 people may have died from the polonium.

The NRPB's new model, based on what it admits are "sparse" data, suggests that much less polonium than once supposed will reach the meat and milk of cows. It implies, The NRPB says, that up to 12 people might have died from the polonium's radioactivity. But this long after the event, it is anybody's guess.

An Assessment of the Radiological Impact of the Windscale Reactor Fire, October 1957, NRPB E3.