Screw your freedom and wear mask

by Arnold Schwarzenegger

August 11, 2021

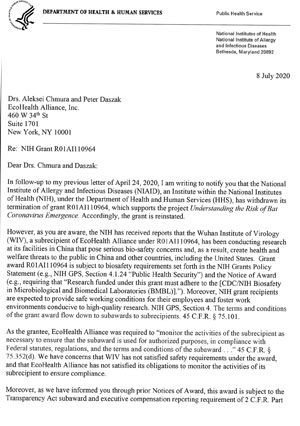

U.S. government gave $3.7 million grant to Wuhan lab at cent

Re: U.S. government gave $3.7 million grant to Wuhan lab at

Part 1 of 2

The origin of COVID: Did people or nature open Pandora’s box at Wuhan?

by Nicholas Wade

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

May 5, 2021

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted lives the world over for more than a year. Its death toll will soon reach three million people. Yet the origin of pandemic remains uncertain: The political agendas of governments and scientists have generated thick clouds of obfuscation, which the mainstream press seems helpless to dispel.

In what follows I will sort through the available scientific facts, which hold many clues as to what happened, and provide readers with the evidence to make their own judgments. I will then try to assess the complex issue of blame, which starts with, but extends far beyond, the government of China.

By the end of this article, you may have learned a lot about the molecular biology of viruses. I will try to keep this process as painless as possible. But the science cannot be avoided because for now, and probably for a long time hence, it offers the only sure thread through the maze.

The virus that caused the pandemic is known officially as SARS-CoV-2, but can be called SARS2 for short. As many people know, there are two main theories about its origin. One is that it jumped naturally from wildlife to people. The other is that the virus was under study in a lab, from which it escaped. It matters a great deal which is the case if we hope to prevent a second such occurrence.

I’ll describe the two theories, explain why each is plausible, and then ask which provides the better explanation of the available facts. It’s important to note that so far there is no direct evidence for either theory. Each depends on a set of reasonable conjectures but so far lacks proof. So I have only clues, not conclusions, to offer. But those clues point in a specific direction. And having inferred that direction, I’m going to delineate some of the strands in this tangled skein of disaster.

A tale of two theories.

After the pandemic first broke out in December 2019, Chinese authorities reported that many cases had occurred in the wet market — a place selling wild animals for meat — in Wuhan. This reminded experts of the SARS1 epidemic of 2002, in which a bat virus had spread first to civets, an animal sold in wet markets, and from civets to people. A similar bat virus caused a second epidemic, known as MERS, in 2012. This time the intermediary host animal was camels.

The decoding of the virus’s genome showed it belonged a viral family known as beta-coronaviruses, to which the SARS1 and MERS viruses also belong. The relationship supported the idea that, like them, it was a natural virus that had managed to jump from bats, via another animal host, to people. The wet market connection, the major point of similarity with the SARS1 and MERS epidemics, was soon broken: Chinese researchers found earlier cases in Wuhan with no link to the wet market. But that seemed not to matter when so much further evidence in support of natural emergence was expected shortly.

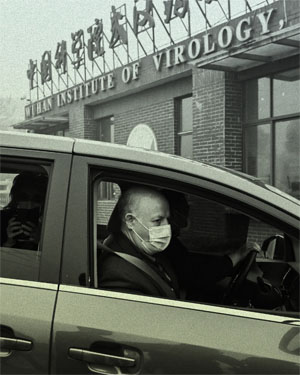

Wuhan, however, is home of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a leading world center for research on coronaviruses. So the possibility that the SARS2 virus had escaped from the lab could not be ruled out. Two reasonable scenarios of origin were on the table.

From early on, public and media perceptions were shaped in favor of the natural emergence scenario by strong statements from two scientific groups. These statements were not at first examined as critically as they should have been.

“We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin,” a group of virologists and others wrote in the Lancet on February 19, 2020, when it was really far too soon for anyone to be sure what had happened. Scientists “overwhelmingly conclude that this coronavirus originated in wildlife,” they said, with a stirring rallying call for readers to stand with Chinese colleagues on the frontline of fighting the disease.

Contrary to the letter writers’ assertion, the idea that the virus might have escaped from a lab invoked accident, not conspiracy. It surely needed to be explored, not rejected out of hand. A defining mark of good scientists is that they go to great pains to distinguish between what they know and what they don’t know. By this criterion, the signatories of the Lancet letter were behaving as poor scientists: They were assuring the public of facts they could not know for sure were true.

It later turned out that the Lancet letter had been organized and drafted by Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance of New York. Daszak’s organization funded coronavirus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. If the SARS2 virus had indeed escaped from research he funded, Daszak would be potentially culpable. This acute conflict of interest was not declared to the Lancet’s readers. To the contrary, the letter concluded, “We declare no competing interests.”

Virologists like Daszak had much at stake in the assigning of blame for the pandemic. For 20 years, mostly beneath the public’s attention, they had been playing a dangerous game. In their laboratories they routinely created viruses more dangerous than those that exist in nature. They argued that they could do so safely, and that by getting ahead of nature they could predict and prevent natural “spillovers,” the cross-over of viruses from an animal host to people. If SARS2 had indeed escaped from such a laboratory experiment, a savage blowback could be expected, and the storm of public indignation would affect virologists everywhere, not just in China. “It would shatter the scientific edifice top to bottom,” an MIT Technology Review editor, Antonio Regalado, said in March 2020.

A second statement that had enormous influence in shaping public attitudes was a letter (in other words an opinion piece, not a scientific article) published on 17 March 2020 in the journal Nature Medicine. Its authors were a group of virologists led by Kristian G. Andersen of the Scripps Research Institute. “Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus,” the five virologists declared in the second paragraph of their letter.

Unfortunately, this was another case of poor science, in the sense defined above. True, some older methods of cutting and pasting viral genomes retain tell-tale signs of manipulation. But newer methods, called “no-see-um” or “seamless” approaches, leave no defining marks. Nor do other methods for manipulating viruses such as serial passage, the repeated transfer of viruses from one culture of cells to another. If a virus has been manipulated, whether with a seamless method or by serial passage, there is no way of knowing that this is the case. Andersen and his colleagues were assuring their readers of something they could not know.

The discussion part of their letter begins, “It is improbable that SARS-CoV-2 emerged through laboratory manipulation of a related SARS-CoV-like coronavirus.” But wait, didn’t the lead say the virus had clearly not been manipulated? The authors’ degree of certainty seemed to slip several notches when it came to laying out their reasoning.

The reason for the slippage is clear once the technical language has been penetrated. The two reasons the authors give for supposing manipulation to be improbable are decidedly inconclusive.

First, they say that the spike protein of SARS2 binds very well to its target, the human ACE2 receptor, but does so in a different way from that which physical calculations suggest would be the best fit. Therefore the virus must have arisen by natural selection, not manipulation.

If this argument seems hard to grasp, it’s because it’s so strained. The authors’ basic assumption, not spelt out, is that anyone trying to make a bat virus bind to human cells could do so in only one way. First they would calculate the strongest possible fit between the human ACE2 receptor and the spike protein with which the virus latches onto it. They would then design the spike protein accordingly (by selecting the right string of amino acid units that compose it). Since the SARS2 spike protein is not of this calculated best design, the Andersen paper says, therefore it can’t have been manipulated.

But this ignores the way that virologists do in fact get spike proteins to bind to chosen targets, which is not by calculation but by splicing in spike protein genes from other viruses or by serial passage. With serial passage, each time the virus’s progeny are transferred to new cell cultures or animals, the more successful are selected until one emerges that makes a really tight bind to human cells. Natural selection has done all the heavy lifting. The Andersen paper’s speculation about designing a viral spike protein through calculation has no bearing on whether or not the virus was manipulated by one of the other two methods.

The authors’ second argument against manipulation is even more contrived. Although most living things use DNA as their hereditary material, a number of viruses use RNA, DNA’s close chemical cousin. But RNA is difficult to manipulate, so researchers working on coronaviruses, which are RNA-based, will first convert the RNA genome to DNA. They manipulate the DNA version, whether by adding or altering genes, and then arrange for the manipulated DNA genome to be converted back into infectious RNA.

Only a certain number of these DNA backbones have been described in the scientific literature. Anyone manipulating the SARS2 virus “would probably” have used one of these known backbones, the Andersen group writes, and since SARS2 is not derived from any of them, therefore it was not manipulated. But the argument is conspicuously inconclusive. DNA backbones are quite easy to make, so it’s obviously possible that SARS2 was manipulated using an unpublished DNA backbone.

And that’s it. These are the two arguments made by the Andersen group in support of their declaration that the SARS2 virus was clearly not manipulated. And this conclusion, grounded in nothing but two inconclusive speculations, convinced the world’s press that SARS2 could not have escaped from a lab. A technical critique of the Andersen letter takes it down in harsher words.

Science is supposedly a self-correcting community of experts who constantly check each other’s work. So why didn’t other virologists point out that the Andersen group’s argument was full of absurdly large holes? Perhaps because in today’s universities speech can be very costly. Careers can be destroyed for stepping out of line. Any virologist who challenges the community’s declared view risks having his next grant application turned down by the panel of fellow virologists that advises the government grant distribution agency.

The Daszak and Andersen letters were really political, not scientific, statements, yet were amazingly effective. Articles in the mainstream press repeatedly stated that a consensus of experts had ruled lab escape out of the question or extremely unlikely. Their authors relied for the most part on the Daszak and Andersen letters, failing to understand the yawning gaps in their arguments. Mainstream newspapers all have science journalists on their staff, as do the major networks, and these specialist reporters are supposed to be able to question scientists and check their assertions. But the Daszak and Andersen assertions went largely unchallenged.

Doubts about natural emergence.

Natural emergence was the media’s preferred theory until around February 2021 and the visit by a World Health Organization (WHO) commission to China. The commission’s composition and access were heavily controlled by the Chinese authorities. Its members, who included the ubiquitous Daszak, kept asserting before, during, and after their visit that lab escape was extremely unlikely. But this was not quite the propaganda victory the Chinese authorities may have been hoping for. What became clear was that the Chinese had no evidence to offer the commission in support of the natural emergence theory.

This was surprising because both the SARS1 and MERS viruses had left copious traces in the environment. The intermediary host species of SARS1 was identified within four months of the epidemic’s outbreak, and the host of MERS within nine months. Yet some 15 months after the SARS2 pandemic began, and after a presumably intensive search, Chinese researchers had failed to find either the original bat population, or the intermediate species to which SARS2 might have jumped, or any serological evidence that any Chinese population, including that of Wuhan, had ever been exposed to the virus prior to December 2019. Natural emergence remained a conjecture which, however plausible to begin with, had gained not a shred of supporting evidence in over a year.

And as long as that remains the case, it’s logical to pay serious attention to the alternative conjecture, that SARS2 escaped from a lab.

Why would anyone want to create a novel virus capable of causing a pandemic? Ever since virologists gained the tools for manipulating a virus’s genes, they have argued they could get ahead of a potential pandemic by exploring how close a given animal virus might be to making the jump to humans. And that justified lab experiments in enhancing the ability of dangerous animal viruses to infect people, virologists asserted.

With this rationale, they have recreated the 1918 flu virus, shown how the almost extinct polio virus can be synthesized from its published DNA sequence, and introduced a smallpox gene into a related virus.

These enhancements of viral capabilities are known blandly as gain-of-function experiments. With coronaviruses, there was particular interest in the spike proteins, which jut out all around the spherical surface of the virus and pretty much determine which species of animal it will target. In 2000 Dutch researchers, for instance, earned the gratitude of rodents everywhere by genetically engineering the spike protein of a mouse coronavirus so that it would attack only cats.

Virologists started studying bat coronaviruses in earnest after these turned out to be the source of both the SARS1 and MERS epidemics. In particular, researchers wanted to understand what changes needed to occur in a bat virus’s spike proteins before it could infect people.

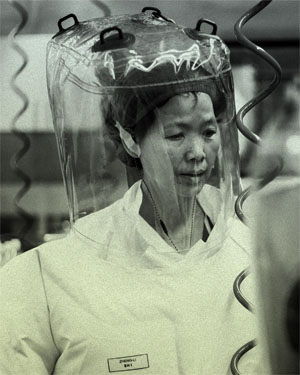

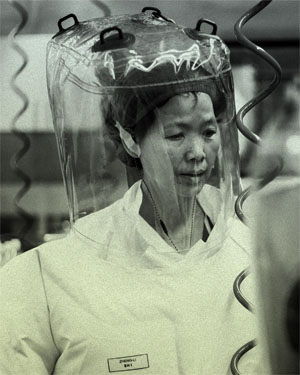

Researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, led by China’s leading expert on bat viruses, Shi Zheng-li or “Bat Lady,” mounted frequent expeditions to the bat-infested caves of Yunnan in southern China and collected around a hundred different bat coronaviruses.

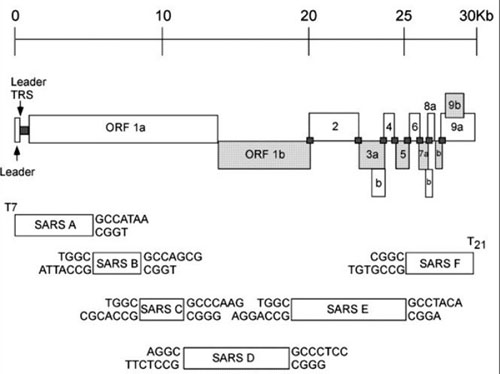

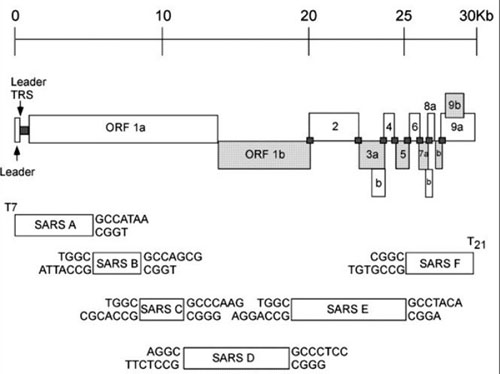

Shi then teamed up with Ralph S. Baric, an eminent coronavirus researcher at the University of North Carolina. Their work focused on enhancing the ability of bat viruses to attack humans so as to “examine the emergence potential (that is, the potential to infect humans) of circulating bat CoVs [coronaviruses].” In pursuit of this aim, in November 2015 they created a novel virus by taking the backbone of the SARS1 virus and replacing its spike protein with one from a bat virus (known as SHC014-CoV). This manufactured virus was able to infect the cells of the human airway, at least when tested against a lab culture of such cells.

The SHC014-CoV/SARS1 virus is known as a chimera because its genome contains genetic material from two strains of virus. If the SARS2 virus were to have been cooked up in Shi’s lab, then its direct prototype would have been the SHC014-CoV/SARS1 chimera, the potential danger of which concerned many observers and prompted intense discussion.

“If the virus escaped, nobody could predict the trajectory,” said Simon Wain-Hobson, a virologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

Baric and Shi referred to the obvious risks in their paper but argued they should be weighed against the benefit of foreshadowing future spillovers. Scientific review panels, they wrote, “may deem similar studies building chimeric viruses based on circulating strains too risky to pursue.” Given various restrictions being placed on gain-of function (GOF) research, matters had arrived in their view at “a crossroads of GOF research concerns; the potential to prepare for and mitigate future outbreaks must be weighed against the risk of creating more dangerous pathogens. In developing policies moving forward, it is important to consider the value of the data generated by these studies and whether these types of chimeric virus studies warrant further investigation versus the inherent risks involved.”

That statement was made in 2015. From the hindsight of 2021, one can say that the value of gain-of-function studies in preventing the SARS2 epidemic was zero. The risk was catastrophic, if indeed the SARS2 virus was generated in a gain-of-function experiment.

Inside the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Baric had developed, and taught Shi, a general method for engineering bat coronaviruses to attack other species. The specific targets were human cells grown in cultures and humanized mice. These laboratory mice, a cheap and ethical stand-in for human subjects, are genetically engineered to carry the human version of a protein called ACE2 that studs the surface of cells that line the airways.

Shi returned to her lab at the Wuhan Institute of Virology and resumed the work she had started on genetically engineering coronaviruses to attack human cells. How can we be so sure?

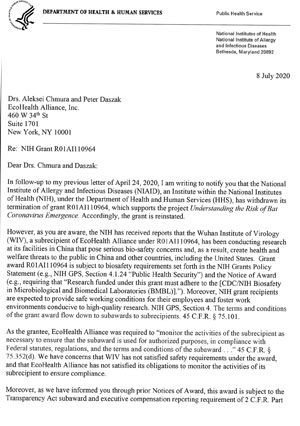

Because, by a strange twist in the story, her work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a part of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). And grant proposals that funded her work, which are a matter of public record, specify exactly what she planned to do with the money.

The grants were assigned to the prime contractor, Daszak of the EcoHealth Alliance, who subcontracted them to Shi. Here are extracts from the grants for fiscal years 2018 and 2019. (“CoV” stands for coronavirus and “S protein” refers to the virus’s spike protein.)

“Test predictions of CoV inter-species transmission. Predictive models of host range (i.e. emergence potential) will be tested experimentally using reverse genetics, pseudovirus and receptor binding assays, and virus infection experiments across a range of cell cultures from different species and humanized mice.”

“We will use S protein sequence data, infectious clone technology, in vitro and in vivo infection experiments and analysis of receptor binding to test the hypothesis that % divergence thresholds in S protein sequences predict spillover potential.”

What this means, in non-technical language, is that Shi set out to create novel coronaviruses with the highest possible infectivity for human cells. Her plan was to take genes that coded for spike proteins possessing a variety of measured affinities for human cells, ranging from high to low. She would insert these spike genes one by one into the backbone of a number of viral genomes (“reverse genetics” and “infectious clone technology”), creating a series of chimeric viruses. These chimeric viruses would then be tested for their ability to attack human cell cultures (“in vitro”) and humanized mice (“in vivo”). And this information would help predict the likelihood of “spillover,” the jump of a coronavirus from bats to people.

The methodical approach was designed to find the best combination of coronavirus backbone and spike protein for infecting human cells. The approach could have generated SARS2-like viruses, and indeed may have created the SARS2 virus itself with the right combination of virus backbone and spike protein.

It cannot yet be stated that Shi did or did not generate SARS2 in her lab because her records have been sealed, but it seems she was certainly on the right track to have done so. “It is clear that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was systematically constructing novel chimeric coronaviruses and was assessing their ability to infect human cells and human-ACE2-expressing mice,” says Richard H. Ebright, a molecular biologist at Rutgers University and leading expert on biosafety.

“It is also clear,” Ebright said, “that, depending on the constant genomic contexts chosen for analysis, this work could have produced SARS-CoV-2 or a proximal progenitor of SARS-CoV-2.” “Genomic context” refers to the particular viral backbone used as the testbed for the spike protein.

The lab escape scenario for the origin of the SARS2 virus, as should by now be evident, is not mere hand-waving in the direction of the Wuhan Institute of Virology. It is a detailed proposal, based on the specific project being funded there by the NIAID.

Even if the grant required the work plan described above, how can we be sure that the plan was in fact carried out? For that we can rely on the word of Daszak, who has been much protesting for the last 15 months that lab escape was a ludicrous conspiracy theory invented by China-bashers.

On December 9, 2019, before the outbreak of the pandemic became generally known, Daszak gave an interview in which he talked in glowing terms of how researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology had been reprogramming the spike protein and generating chimeric coronaviruses capable of infecting humanized mice.

“And we have now found, you know, after 6 or 7 years of doing this, over 100 new SARS-related coronaviruses, very close to SARS,” Daszak says around minute 28 of the interview. “Some of them get into human cells in the lab, some of them can cause SARS disease in humanized mice models and are untreatable with therapeutic monoclonals and you can’t vaccinate against them with a vaccine. So, these are a clear and present danger….

“Interviewer: You say these are diverse coronaviruses and you can’t vaccinate against them, and no anti-virals — so what do we do?

“Daszak: Well I think…coronaviruses — you can manipulate them in the lab pretty easily. Spike protein drives a lot of what happen with coronavirus, in zoonotic risk. So you can get the sequence, you can build the protein, and we work a lot with Ralph Baric at UNC to do this. Insert into the backbone of another virus and do some work in the lab. So you can get more predictive when you find a sequence. You’ve got this diversity. Now the logical progression for vaccines is, if you are going to develop a vaccine for SARS, people are going to use pandemic SARS, but let’s insert some of these other things and get a better vaccine.” The insertions he referred to perhaps included an element called the furin cleavage site, discussed below, which greatly increases viral infectivity for human cells.

In disjointed style, Daszak is referring to the fact that once you have generated a novel coronavirus that can attack human cells, you can take the spike protein and make it the basis for a vaccine.

One can only imagine Daszak’s reaction when he heard of the outbreak of the epidemic in Wuhan a few days later. He would have known better than anyone the Wuhan Institute’s goal of making bat coronaviruses infectious to humans, as well as the weaknesses in the institute’s defense against their own researchers becoming infected.

But instead of providing public health authorities with the plentiful information at his disposal, he immediately launched a public relations campaign to persuade the world that the epidemic couldn’t possibly have been caused by one of the institute’s souped-up viruses. “The idea that this virus escaped from a lab is just pure baloney. It’s simply not true,” he declared in an April 2020 interview.

The safety arrangements at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Daszak was possibly unaware of, or perhaps he knew all too well, the long history of viruses escaping from even the best run laboratories. The smallpox virus escaped three times from labs in England in the 1960’s and 1970’s, causing 80 cases and 3 deaths. Dangerous viruses have leaked out of labs almost every year since. Coming to more recent times, the SARS1 virus has proved a true escape artist, leaking from laboratories in Singapore, Taiwan, and no less than four times from the Chinese National Institute of Virology in Beijing.

One reason for SARS1 being so hard to handle is that there were no vaccines available to protect laboratory workers. As Daszak mentioned in the December 19 interview quoted above, the Wuhan researchers too had been unable to develop vaccines against the coronaviruses they had designed to infect human cells. They would have been as defenseless against the SARS2 virus, if it were generated in their lab, as their Beijing colleagues were against SARS1.

A second reason for the severe danger of novel coronaviruses has to do with the required levels of lab safety. There are four degrees of safety, designated BSL1 to BSL4, with BSL4 being the most restrictive and designed for deadly pathogens like the Ebola virus.

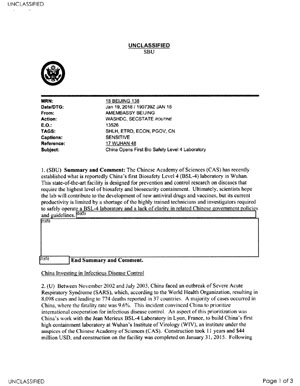

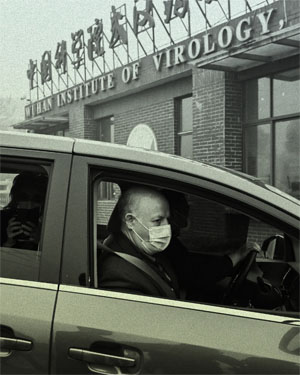

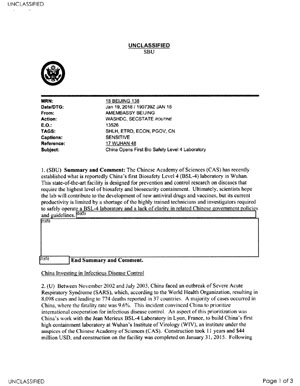

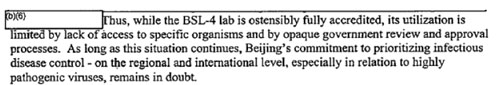

The Wuhan Institute of Virology had a new BSL4 lab, but its state of readiness considerably alarmed the State Department inspectors who visited it from the Beijing embassy in 2018. “The new lab has a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory,” the inspectors wrote in a cable of January 19, 2018.

The real problem, however, was not the unsafe state of the Wuhan BSL4 lab but the fact that virologists worldwide don’t like working in BSL4 conditions. You have to wear a space suit, do operations in closed cabinets, and accept that everything will take twice as long. So the rules assigning each kind of virus to a given safety level were laxer than some might think was prudent.

Before 2020, the rules followed by virologists in China and elsewhere required that experiments with the SARS1 and MERS viruses be conducted in BSL3 conditions. But all other bat coronaviruses could be studied in BSL2, the next level down. BSL2 requires taking fairly minimal safety precautions, such as wearing lab coats and gloves, not sucking up liquids in a pipette, and putting up biohazard warning signs. Yet a gain-of-function experiment conducted in BSL2 might produce an agent more infectious than either SARS1 or MERS. And if it did, then lab workers would stand a high chance of infection, especially if unvaccinated.

Much of Shi’s work on gain-of-function in coronaviruses was performed at the BSL2 safety level, as is stated in her publications and other documents. She has said in an interview with Science magazine that “[t]he coronavirus research in our laboratory is conducted in BSL-2 or BSL-3 laboratories.”

“It is clear that some or all of this work was being performed using a biosafety standard — biosafety level 2, the biosafety level of a standard US dentist’s office — that would pose an unacceptably high risk of infection of laboratory staff upon contact with a virus having the transmission properties of SARS-CoV-2,” Ebright says.

“It also is clear,” he adds, “that this work never should have been funded and never should have been performed.”

This is a view he holds regardless of whether or not the SARS2 virus ever saw the inside of a lab.

Concern about safety conditions at the Wuhan lab was not, it seems, misplaced. According to a fact sheet issued by the State Department on January 15, 2021, “The U.S. government has reason to believe that several researchers inside the WIV became sick in autumn 2019, before the first identified case of the outbreak, with symptoms consistent with both COVID-19 and common seasonal illnesses.”

David Asher, a fellow of the Hudson Institute and former consultant to the State Department, provided more detail about the incident at a seminar. Knowledge of the incident came from a mix of public information and “some high end information collected by our intelligence community,” he said. Three people working at a BSL3 lab at the institute fell sick within a week of each other with severe symptoms that required hospitalization. This was “the first known cluster that we’re aware of, of victims of what we believe to be COVID-19.” Influenza could not completely be ruled out but seemed unlikely in the circumstances, he said.

Comparing the rival scenarios of SARS2 origin.

The evidence above adds up to a serious case that the SARS2 virus could have been created in a lab, from which it then escaped. But the case, however substantial, falls short of proof. Proof would consist of evidence from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, or related labs in Wuhan, that SARS2 or a predecessor virus was under development there. For lack of access to such records, another approach is to take certain salient facts about the SARS2 virus and ask how well each is explained by the two rival scenarios of origin, those of natural emergence and lab escape. Here are four tests of the two hypotheses. A couple have some technical detail, but these are among the most persuasive for those who may care to follow the argument.

The origin of COVID: Did people or nature open Pandora’s box at Wuhan?

by Nicholas Wade

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

May 5, 2021

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

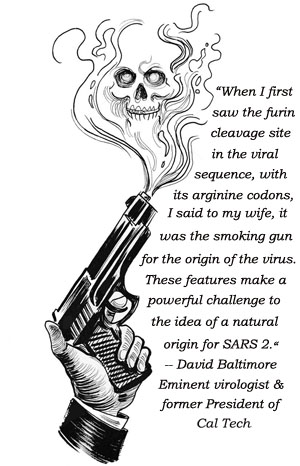

“When I first saw the furin cleavage site in the viral sequence, with its arginine codons, I said to my wife it was the smoking gun for the origin of the virus,” said David Baltimore, an eminent virologist and former president of CalTech. “These features make a powerful challenge to the idea of a natural origin for SARS2,” he said.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted lives the world over for more than a year. Its death toll will soon reach three million people. Yet the origin of pandemic remains uncertain: The political agendas of governments and scientists have generated thick clouds of obfuscation, which the mainstream press seems helpless to dispel.

In what follows I will sort through the available scientific facts, which hold many clues as to what happened, and provide readers with the evidence to make their own judgments. I will then try to assess the complex issue of blame, which starts with, but extends far beyond, the government of China.

By the end of this article, you may have learned a lot about the molecular biology of viruses. I will try to keep this process as painless as possible. But the science cannot be avoided because for now, and probably for a long time hence, it offers the only sure thread through the maze.

The virus that caused the pandemic is known officially as SARS-CoV-2, but can be called SARS2 for short. As many people know, there are two main theories about its origin. One is that it jumped naturally from wildlife to people. The other is that the virus was under study in a lab, from which it escaped. It matters a great deal which is the case if we hope to prevent a second such occurrence.

I’ll describe the two theories, explain why each is plausible, and then ask which provides the better explanation of the available facts. It’s important to note that so far there is no direct evidence for either theory. Each depends on a set of reasonable conjectures but so far lacks proof. So I have only clues, not conclusions, to offer. But those clues point in a specific direction. And having inferred that direction, I’m going to delineate some of the strands in this tangled skein of disaster.

A tale of two theories.

After the pandemic first broke out in December 2019, Chinese authorities reported that many cases had occurred in the wet market — a place selling wild animals for meat — in Wuhan. This reminded experts of the SARS1 epidemic of 2002, in which a bat virus had spread first to civets, an animal sold in wet markets, and from civets to people. A similar bat virus caused a second epidemic, known as MERS, in 2012. This time the intermediary host animal was camels.

The decoding of the virus’s genome showed it belonged a viral family known as beta-coronaviruses, to which the SARS1 and MERS viruses also belong. The relationship supported the idea that, like them, it was a natural virus that had managed to jump from bats, via another animal host, to people. The wet market connection, the major point of similarity with the SARS1 and MERS epidemics, was soon broken: Chinese researchers found earlier cases in Wuhan with no link to the wet market. But that seemed not to matter when so much further evidence in support of natural emergence was expected shortly.

Wuhan, however, is home of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, a leading world center for research on coronaviruses. So the possibility that the SARS2 virus had escaped from the lab could not be ruled out. Two reasonable scenarios of origin were on the table.

From early on, public and media perceptions were shaped in favor of the natural emergence scenario by strong statements from two scientific groups. These statements were not at first examined as critically as they should have been.

“We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin,” a group of virologists and others wrote in the Lancet on February 19, 2020, when it was really far too soon for anyone to be sure what had happened. Scientists “overwhelmingly conclude that this coronavirus originated in wildlife,” they said, with a stirring rallying call for readers to stand with Chinese colleagues on the frontline of fighting the disease.

Contrary to the letter writers’ assertion, the idea that the virus might have escaped from a lab invoked accident, not conspiracy. It surely needed to be explored, not rejected out of hand. A defining mark of good scientists is that they go to great pains to distinguish between what they know and what they don’t know. By this criterion, the signatories of the Lancet letter were behaving as poor scientists: They were assuring the public of facts they could not know for sure were true.

It later turned out that the Lancet letter had been organized and drafted by Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance of New York. Daszak’s organization funded coronavirus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. If the SARS2 virus had indeed escaped from research he funded, Daszak would be potentially culpable. This acute conflict of interest was not declared to the Lancet’s readers. To the contrary, the letter concluded, “We declare no competing interests.”

Virologists like Daszak had much at stake in the assigning of blame for the pandemic. For 20 years, mostly beneath the public’s attention, they had been playing a dangerous game. In their laboratories they routinely created viruses more dangerous than those that exist in nature. They argued that they could do so safely, and that by getting ahead of nature they could predict and prevent natural “spillovers,” the cross-over of viruses from an animal host to people. If SARS2 had indeed escaped from such a laboratory experiment, a savage blowback could be expected, and the storm of public indignation would affect virologists everywhere, not just in China. “It would shatter the scientific edifice top to bottom,” an MIT Technology Review editor, Antonio Regalado, said in March 2020.

A second statement that had enormous influence in shaping public attitudes was a letter (in other words an opinion piece, not a scientific article) published on 17 March 2020 in the journal Nature Medicine. Its authors were a group of virologists led by Kristian G. Andersen of the Scripps Research Institute. “Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus,” the five virologists declared in the second paragraph of their letter.

Unfortunately, this was another case of poor science, in the sense defined above. True, some older methods of cutting and pasting viral genomes retain tell-tale signs of manipulation. But newer methods, called “no-see-um” or “seamless” approaches, leave no defining marks. Nor do other methods for manipulating viruses such as serial passage, the repeated transfer of viruses from one culture of cells to another. If a virus has been manipulated, whether with a seamless method or by serial passage, there is no way of knowing that this is the case. Andersen and his colleagues were assuring their readers of something they could not know.

The discussion part of their letter begins, “It is improbable that SARS-CoV-2 emerged through laboratory manipulation of a related SARS-CoV-like coronavirus.” But wait, didn’t the lead say the virus had clearly not been manipulated? The authors’ degree of certainty seemed to slip several notches when it came to laying out their reasoning.

The reason for the slippage is clear once the technical language has been penetrated. The two reasons the authors give for supposing manipulation to be improbable are decidedly inconclusive.

First, they say that the spike protein of SARS2 binds very well to its target, the human ACE2 receptor, but does so in a different way from that which physical calculations suggest would be the best fit. Therefore the virus must have arisen by natural selection, not manipulation.

If this argument seems hard to grasp, it’s because it’s so strained. The authors’ basic assumption, not spelt out, is that anyone trying to make a bat virus bind to human cells could do so in only one way. First they would calculate the strongest possible fit between the human ACE2 receptor and the spike protein with which the virus latches onto it. They would then design the spike protein accordingly (by selecting the right string of amino acid units that compose it). Since the SARS2 spike protein is not of this calculated best design, the Andersen paper says, therefore it can’t have been manipulated.

But this ignores the way that virologists do in fact get spike proteins to bind to chosen targets, which is not by calculation but by splicing in spike protein genes from other viruses or by serial passage. With serial passage, each time the virus’s progeny are transferred to new cell cultures or animals, the more successful are selected until one emerges that makes a really tight bind to human cells. Natural selection has done all the heavy lifting. The Andersen paper’s speculation about designing a viral spike protein through calculation has no bearing on whether or not the virus was manipulated by one of the other two methods.

The authors’ second argument against manipulation is even more contrived. Although most living things use DNA as their hereditary material, a number of viruses use RNA, DNA’s close chemical cousin. But RNA is difficult to manipulate, so researchers working on coronaviruses, which are RNA-based, will first convert the RNA genome to DNA. They manipulate the DNA version, whether by adding or altering genes, and then arrange for the manipulated DNA genome to be converted back into infectious RNA.

Only a certain number of these DNA backbones have been described in the scientific literature. Anyone manipulating the SARS2 virus “would probably” have used one of these known backbones, the Andersen group writes, and since SARS2 is not derived from any of them, therefore it was not manipulated. But the argument is conspicuously inconclusive. DNA backbones are quite easy to make, so it’s obviously possible that SARS2 was manipulated using an unpublished DNA backbone.

And that’s it. These are the two arguments made by the Andersen group in support of their declaration that the SARS2 virus was clearly not manipulated. And this conclusion, grounded in nothing but two inconclusive speculations, convinced the world’s press that SARS2 could not have escaped from a lab. A technical critique of the Andersen letter takes it down in harsher words.

Science is supposedly a self-correcting community of experts who constantly check each other’s work. So why didn’t other virologists point out that the Andersen group’s argument was full of absurdly large holes? Perhaps because in today’s universities speech can be very costly. Careers can be destroyed for stepping out of line. Any virologist who challenges the community’s declared view risks having his next grant application turned down by the panel of fellow virologists that advises the government grant distribution agency.

The Daszak and Andersen letters were really political, not scientific, statements, yet were amazingly effective. Articles in the mainstream press repeatedly stated that a consensus of experts had ruled lab escape out of the question or extremely unlikely. Their authors relied for the most part on the Daszak and Andersen letters, failing to understand the yawning gaps in their arguments. Mainstream newspapers all have science journalists on their staff, as do the major networks, and these specialist reporters are supposed to be able to question scientists and check their assertions. But the Daszak and Andersen assertions went largely unchallenged.

Doubts about natural emergence.

Natural emergence was the media’s preferred theory until around February 2021 and the visit by a World Health Organization (WHO) commission to China. The commission’s composition and access were heavily controlled by the Chinese authorities. Its members, who included the ubiquitous Daszak, kept asserting before, during, and after their visit that lab escape was extremely unlikely. But this was not quite the propaganda victory the Chinese authorities may have been hoping for. What became clear was that the Chinese had no evidence to offer the commission in support of the natural emergence theory.

This was surprising because both the SARS1 and MERS viruses had left copious traces in the environment. The intermediary host species of SARS1 was identified within four months of the epidemic’s outbreak, and the host of MERS within nine months. Yet some 15 months after the SARS2 pandemic began, and after a presumably intensive search, Chinese researchers had failed to find either the original bat population, or the intermediate species to which SARS2 might have jumped, or any serological evidence that any Chinese population, including that of Wuhan, had ever been exposed to the virus prior to December 2019. Natural emergence remained a conjecture which, however plausible to begin with, had gained not a shred of supporting evidence in over a year.

And as long as that remains the case, it’s logical to pay serious attention to the alternative conjecture, that SARS2 escaped from a lab.

Why would anyone want to create a novel virus capable of causing a pandemic? Ever since virologists gained the tools for manipulating a virus’s genes, they have argued they could get ahead of a potential pandemic by exploring how close a given animal virus might be to making the jump to humans. And that justified lab experiments in enhancing the ability of dangerous animal viruses to infect people, virologists asserted.

With this rationale, they have recreated the 1918 flu virus, shown how the almost extinct polio virus can be synthesized from its published DNA sequence, and introduced a smallpox gene into a related virus.

These enhancements of viral capabilities are known blandly as gain-of-function experiments. With coronaviruses, there was particular interest in the spike proteins, which jut out all around the spherical surface of the virus and pretty much determine which species of animal it will target. In 2000 Dutch researchers, for instance, earned the gratitude of rodents everywhere by genetically engineering the spike protein of a mouse coronavirus so that it would attack only cats.

Virologists started studying bat coronaviruses in earnest after these turned out to be the source of both the SARS1 and MERS epidemics. In particular, researchers wanted to understand what changes needed to occur in a bat virus’s spike proteins before it could infect people.

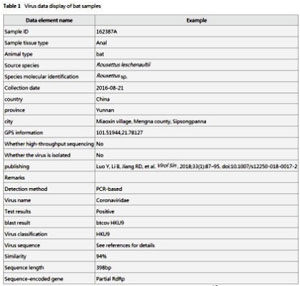

Researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, led by China’s leading expert on bat viruses, Shi Zheng-li or “Bat Lady,” mounted frequent expeditions to the bat-infested caves of Yunnan in southern China and collected around a hundred different bat coronaviruses.

Shi then teamed up with Ralph S. Baric, an eminent coronavirus researcher at the University of North Carolina. Their work focused on enhancing the ability of bat viruses to attack humans so as to “examine the emergence potential (that is, the potential to infect humans) of circulating bat CoVs [coronaviruses].” In pursuit of this aim, in November 2015 they created a novel virus by taking the backbone of the SARS1 virus and replacing its spike protein with one from a bat virus (known as SHC014-CoV). This manufactured virus was able to infect the cells of the human airway, at least when tested against a lab culture of such cells.

The SHC014-CoV/SARS1 virus is known as a chimera because its genome contains genetic material from two strains of virus. If the SARS2 virus were to have been cooked up in Shi’s lab, then its direct prototype would have been the SHC014-CoV/SARS1 chimera, the potential danger of which concerned many observers and prompted intense discussion.

“If the virus escaped, nobody could predict the trajectory,” said Simon Wain-Hobson, a virologist at the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

Baric and Shi referred to the obvious risks in their paper but argued they should be weighed against the benefit of foreshadowing future spillovers. Scientific review panels, they wrote, “may deem similar studies building chimeric viruses based on circulating strains too risky to pursue.” Given various restrictions being placed on gain-of function (GOF) research, matters had arrived in their view at “a crossroads of GOF research concerns; the potential to prepare for and mitigate future outbreaks must be weighed against the risk of creating more dangerous pathogens. In developing policies moving forward, it is important to consider the value of the data generated by these studies and whether these types of chimeric virus studies warrant further investigation versus the inherent risks involved.”

That statement was made in 2015. From the hindsight of 2021, one can say that the value of gain-of-function studies in preventing the SARS2 epidemic was zero. The risk was catastrophic, if indeed the SARS2 virus was generated in a gain-of-function experiment.

Inside the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Baric had developed, and taught Shi, a general method for engineering bat coronaviruses to attack other species. The specific targets were human cells grown in cultures and humanized mice. These laboratory mice, a cheap and ethical stand-in for human subjects, are genetically engineered to carry the human version of a protein called ACE2 that studs the surface of cells that line the airways.

Shi returned to her lab at the Wuhan Institute of Virology and resumed the work she had started on genetically engineering coronaviruses to attack human cells. How can we be so sure?

Because, by a strange twist in the story, her work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a part of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). And grant proposals that funded her work, which are a matter of public record, specify exactly what she planned to do with the money.

The grants were assigned to the prime contractor, Daszak of the EcoHealth Alliance, who subcontracted them to Shi. Here are extracts from the grants for fiscal years 2018 and 2019. (“CoV” stands for coronavirus and “S protein” refers to the virus’s spike protein.)

“Test predictions of CoV inter-species transmission. Predictive models of host range (i.e. emergence potential) will be tested experimentally using reverse genetics, pseudovirus and receptor binding assays, and virus infection experiments across a range of cell cultures from different species and humanized mice.”

“We will use S protein sequence data, infectious clone technology, in vitro and in vivo infection experiments and analysis of receptor binding to test the hypothesis that % divergence thresholds in S protein sequences predict spillover potential.”

What this means, in non-technical language, is that Shi set out to create novel coronaviruses with the highest possible infectivity for human cells. Her plan was to take genes that coded for spike proteins possessing a variety of measured affinities for human cells, ranging from high to low. She would insert these spike genes one by one into the backbone of a number of viral genomes (“reverse genetics” and “infectious clone technology”), creating a series of chimeric viruses. These chimeric viruses would then be tested for their ability to attack human cell cultures (“in vitro”) and humanized mice (“in vivo”). And this information would help predict the likelihood of “spillover,” the jump of a coronavirus from bats to people.

The methodical approach was designed to find the best combination of coronavirus backbone and spike protein for infecting human cells. The approach could have generated SARS2-like viruses, and indeed may have created the SARS2 virus itself with the right combination of virus backbone and spike protein.

It cannot yet be stated that Shi did or did not generate SARS2 in her lab because her records have been sealed, but it seems she was certainly on the right track to have done so. “It is clear that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was systematically constructing novel chimeric coronaviruses and was assessing their ability to infect human cells and human-ACE2-expressing mice,” says Richard H. Ebright, a molecular biologist at Rutgers University and leading expert on biosafety.

“It is also clear,” Ebright said, “that, depending on the constant genomic contexts chosen for analysis, this work could have produced SARS-CoV-2 or a proximal progenitor of SARS-CoV-2.” “Genomic context” refers to the particular viral backbone used as the testbed for the spike protein.

The lab escape scenario for the origin of the SARS2 virus, as should by now be evident, is not mere hand-waving in the direction of the Wuhan Institute of Virology. It is a detailed proposal, based on the specific project being funded there by the NIAID.

Even if the grant required the work plan described above, how can we be sure that the plan was in fact carried out? For that we can rely on the word of Daszak, who has been much protesting for the last 15 months that lab escape was a ludicrous conspiracy theory invented by China-bashers.

On December 9, 2019, before the outbreak of the pandemic became generally known, Daszak gave an interview in which he talked in glowing terms of how researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology had been reprogramming the spike protein and generating chimeric coronaviruses capable of infecting humanized mice.

“And we have now found, you know, after 6 or 7 years of doing this, over 100 new SARS-related coronaviruses, very close to SARS,” Daszak says around minute 28 of the interview. “Some of them get into human cells in the lab, some of them can cause SARS disease in humanized mice models and are untreatable with therapeutic monoclonals and you can’t vaccinate against them with a vaccine. So, these are a clear and present danger….

“Interviewer: You say these are diverse coronaviruses and you can’t vaccinate against them, and no anti-virals — so what do we do?

“Daszak: Well I think…coronaviruses — you can manipulate them in the lab pretty easily. Spike protein drives a lot of what happen with coronavirus, in zoonotic risk. So you can get the sequence, you can build the protein, and we work a lot with Ralph Baric at UNC to do this. Insert into the backbone of another virus and do some work in the lab. So you can get more predictive when you find a sequence. You’ve got this diversity. Now the logical progression for vaccines is, if you are going to develop a vaccine for SARS, people are going to use pandemic SARS, but let’s insert some of these other things and get a better vaccine.” The insertions he referred to perhaps included an element called the furin cleavage site, discussed below, which greatly increases viral infectivity for human cells.

In disjointed style, Daszak is referring to the fact that once you have generated a novel coronavirus that can attack human cells, you can take the spike protein and make it the basis for a vaccine.

One can only imagine Daszak’s reaction when he heard of the outbreak of the epidemic in Wuhan a few days later. He would have known better than anyone the Wuhan Institute’s goal of making bat coronaviruses infectious to humans, as well as the weaknesses in the institute’s defense against their own researchers becoming infected.

But instead of providing public health authorities with the plentiful information at his disposal, he immediately launched a public relations campaign to persuade the world that the epidemic couldn’t possibly have been caused by one of the institute’s souped-up viruses. “The idea that this virus escaped from a lab is just pure baloney. It’s simply not true,” he declared in an April 2020 interview.

The safety arrangements at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Daszak was possibly unaware of, or perhaps he knew all too well, the long history of viruses escaping from even the best run laboratories. The smallpox virus escaped three times from labs in England in the 1960’s and 1970’s, causing 80 cases and 3 deaths. Dangerous viruses have leaked out of labs almost every year since. Coming to more recent times, the SARS1 virus has proved a true escape artist, leaking from laboratories in Singapore, Taiwan, and no less than four times from the Chinese National Institute of Virology in Beijing.

One reason for SARS1 being so hard to handle is that there were no vaccines available to protect laboratory workers. As Daszak mentioned in the December 19 interview quoted above, the Wuhan researchers too had been unable to develop vaccines against the coronaviruses they had designed to infect human cells. They would have been as defenseless against the SARS2 virus, if it were generated in their lab, as their Beijing colleagues were against SARS1.

A second reason for the severe danger of novel coronaviruses has to do with the required levels of lab safety. There are four degrees of safety, designated BSL1 to BSL4, with BSL4 being the most restrictive and designed for deadly pathogens like the Ebola virus.

The Wuhan Institute of Virology had a new BSL4 lab, but its state of readiness considerably alarmed the State Department inspectors who visited it from the Beijing embassy in 2018. “The new lab has a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory,” the inspectors wrote in a cable of January 19, 2018.

The real problem, however, was not the unsafe state of the Wuhan BSL4 lab but the fact that virologists worldwide don’t like working in BSL4 conditions. You have to wear a space suit, do operations in closed cabinets, and accept that everything will take twice as long. So the rules assigning each kind of virus to a given safety level were laxer than some might think was prudent.

Before 2020, the rules followed by virologists in China and elsewhere required that experiments with the SARS1 and MERS viruses be conducted in BSL3 conditions. But all other bat coronaviruses could be studied in BSL2, the next level down. BSL2 requires taking fairly minimal safety precautions, such as wearing lab coats and gloves, not sucking up liquids in a pipette, and putting up biohazard warning signs. Yet a gain-of-function experiment conducted in BSL2 might produce an agent more infectious than either SARS1 or MERS. And if it did, then lab workers would stand a high chance of infection, especially if unvaccinated.

Much of Shi’s work on gain-of-function in coronaviruses was performed at the BSL2 safety level, as is stated in her publications and other documents. She has said in an interview with Science magazine that “[t]he coronavirus research in our laboratory is conducted in BSL-2 or BSL-3 laboratories.”

“It is clear that some or all of this work was being performed using a biosafety standard — biosafety level 2, the biosafety level of a standard US dentist’s office — that would pose an unacceptably high risk of infection of laboratory staff upon contact with a virus having the transmission properties of SARS-CoV-2,” Ebright says.

“It also is clear,” he adds, “that this work never should have been funded and never should have been performed.”

This is a view he holds regardless of whether or not the SARS2 virus ever saw the inside of a lab.

Concern about safety conditions at the Wuhan lab was not, it seems, misplaced. According to a fact sheet issued by the State Department on January 15, 2021, “The U.S. government has reason to believe that several researchers inside the WIV became sick in autumn 2019, before the first identified case of the outbreak, with symptoms consistent with both COVID-19 and common seasonal illnesses.”

David Asher, a fellow of the Hudson Institute and former consultant to the State Department, provided more detail about the incident at a seminar. Knowledge of the incident came from a mix of public information and “some high end information collected by our intelligence community,” he said. Three people working at a BSL3 lab at the institute fell sick within a week of each other with severe symptoms that required hospitalization. This was “the first known cluster that we’re aware of, of victims of what we believe to be COVID-19.” Influenza could not completely be ruled out but seemed unlikely in the circumstances, he said.

Comparing the rival scenarios of SARS2 origin.

The evidence above adds up to a serious case that the SARS2 virus could have been created in a lab, from which it then escaped. But the case, however substantial, falls short of proof. Proof would consist of evidence from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, or related labs in Wuhan, that SARS2 or a predecessor virus was under development there. For lack of access to such records, another approach is to take certain salient facts about the SARS2 virus and ask how well each is explained by the two rival scenarios of origin, those of natural emergence and lab escape. Here are four tests of the two hypotheses. A couple have some technical detail, but these are among the most persuasive for those who may care to follow the argument.

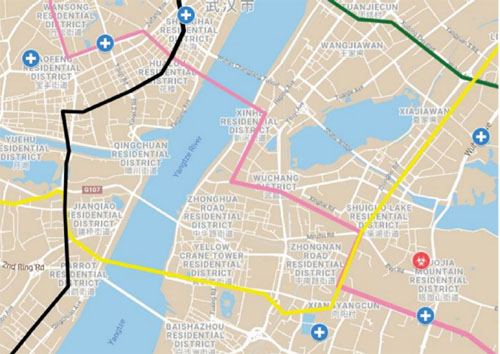

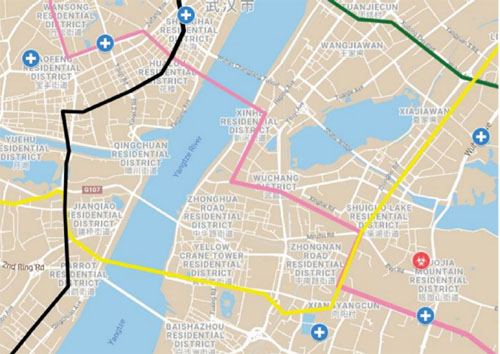

1) The place of origin. Start with geography. The two closest known relatives of the SARS2 virus were collected from bats living in caves in Yunnan, a province of southern China. If the SARS2 virus had first infected people living around the Yunnan caves, that would strongly support the idea that the virus had spilled over to people naturally. But this isn’t what happened. The pandemic broke out 1,500 kilometers away, in Wuhan.

Beta-coronaviruses, the family of bat viruses to which SARS2 belongs, infect the horseshoe bat Rhinolophus affinis, which ranges across southern China. The bats’ range is 50 kilometers, so it’s unlikely that any made it to Wuhan. In any case, the first cases of the COVID-19 pandemic probably occurred in September, when temperatures in Hubei province are already cold enough to send bats into hibernation.

What if the bat viruses infected some intermediate host first? You would need a longstanding population of bats in frequent proximity with an intermediate host, which in turn must often cross paths with people. All these exchanges of virus must take place somewhere outside Wuhan, a busy metropolis which so far as is known is not a natural habitat of Rhinolophus bat colonies. The infected person (or animal) carrying this highly transmissible virus must have traveled to Wuhan without infecting anyone else. No one in his or her family got sick. If the person jumped on a train to Wuhan, no fellow passengers fell ill.

It’s a stretch, in other words, to get the pandemic to break out naturally outside Wuhan and then, without leaving any trace, to make its first appearance there.

For the lab escape scenario, a Wuhan origin for the virus is a no-brainer. Wuhan is home to China’s leading center of coronavirus research where, as noted above, researchers were genetically engineering bat coronaviruses to attack human cells. They were doing so under the minimal safety conditions of a BSL2 lab. If a virus with the unexpected infectiousness of SARS2 had been generated there, its escape would be no surprise.

2) Natural history and evolution. The initial location of the pandemic is a small part of a larger problem, that of its natural history. Viruses don’t just make one time jumps from one species to another. The coronavirus spike protein, adapted to attack bat cells, needs repeated jumps to another species, most of which fail, before it gains a lucky mutation. Mutation — a change in one of its RNA units — causes a different amino acid unit to be incorporated into its spike protein and makes the spike protein better able to attack the cells of some other species.

Through several more such mutation-driven adjustments, the virus adapts to its new host, say some animal with which bats are in frequent contact. The whole process then resumes as the virus moves from this intermediate host to people.

In the case of SARS1, researchers have documented the successive changes in its spike protein as the virus evolved step by step into a dangerous pathogen. After it had gotten from bats into civets, there were six further changes in its spike protein before it became a mild pathogen in people. After a further 14 changes, the virus was much better adapted to humans, and with a further four, the epidemic took off.

But when you look for the fingerprints of a similar transition in SARS2, a strange surprise awaits. The virus has changed hardly at all, at least until recently. From its very first appearance, it was well adapted to human cells. Researchers led by Alina Chan of the Broad Institute compared SARS2 with late stage SARS1, which by then was well adapted to human cells, and found that the two viruses were similarly well adapted. “By the time SARS-CoV-2 was first detected in late 2019, it was already pre-adapted to human transmission to an extent similar to late epidemic SARS-CoV,” they wrote.

Even those who think lab origin unlikely agree that SARS2 genomes are remarkably uniform. Baric writes that “early strains identified in Wuhan, China, showed limited genetic diversity, which suggests that the virus may have been introduced from a single source.”

A single source would of course be compatible with lab escape, less so with the massive variation and selection which is evolution’s hallmark way of doing business.

The uniform structure of SARS2 genomes gives no hint of any passage through an intermediate animal host, and no such host has been identified in nature.

Proponents of natural emergence suggest that SARS2 incubated in a yet-to-be found human population before gaining its special properties. Or that it jumped to a host animal outside China.

All these conjectures are possible, but strained. Proponents of a lab leak have a simpler explanation. SARS2 was adapted to human cells from the start because it was grown in humanized mice or in lab cultures of human cells, just as described in Daszak’s grant proposal. Its genome shows little diversity because the hallmark of lab cultures is uniformity.

Proponents of laboratory escape joke that of course the SARS2 virus infected an intermediary host species before spreading to people, and that they have identified it — a humanized mouse from the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

3) The furin cleavage site. The furin cleavage site is a minute part of the virus’s anatomy but one that exerts great influence on its infectivity. It sits in the middle of the SARS2 spike protein. It also lies at the heart of the puzzle of where the virus came from.

The spike protein has two sub-units with different roles. The first, called S1, recognizes the virus’s target, a protein called angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (or ACE2) which studs the surface of cells lining the human airways. The second, S2, helps the virus, once anchored to the cell, to fuse with the cell’s membrane. After the virus’s outer membrane has coalesced with that of the stricken cell, the viral genome is injected into the cell, hijacks its protein-making machinery and forces it to generate new viruses.

But this invasion cannot begin until the S1 and S2 subunits have been cut apart. And there, right at the S1/S2 junction, is the furin cleavage site that ensures the spike protein will be cleaved in exactly the right place.

The virus, a model of economic design, does not carry its own cleaver. It relies on the cell to do the cleaving for it. Human cells have a protein cutting tool on their surface known as furin. Furin will cut any protein chain that carries its signature target cutting site. This is the sequence of amino acid units proline-arginine-arginine-alanine, or PRRA in the code that refers to each amino acid by a letter of the alphabet. PRRA is the amino acid sequence at the core of SARS2’s furin cleavage site.

Viruses have all kinds of clever tricks, so why does the furin cleavage site stand out? Because of all known SARS-related beta-coronaviruses, only SARS2 possesses a furin cleavage site. All the other viruses have their S2 unit cleaved at a different site and by a different mechanism.

How then did SARS2 acquire its furin cleavage site? Either the site evolved naturally, or it was inserted by researchers at the S1/S2 junction in a gain-of-function experiment.

Consider natural origin first. Two ways viruses evolve are by mutation and by recombination. Mutation is the process of random change in DNA (or RNA for coronaviruses) that usually results in one amino acid in a protein chain being switched for another. Many of these changes harm the virus but natural selection retains the few that do something useful. Mutation is the process by which the SARS1 spike protein gradually switched its preferred target cells from those of bats to civets, and then to humans.

Mutation seems a less likely way for SARS2’s furin cleavage site to be generated, even though it can’t completely be ruled out. The site’s four amino acid units are all together, and all at just the right place in the S1/S2 junction. Mutation is a random process triggered by copying errors (when new viral genomes are being generated) or by chemical decay of genomic units. So it typically affects single amino acids at different spots in a protein chain. A string of amino acids like that of the furin cleavage site is much more likely to be acquired all together through a quite different process known as recombination.

Recombination is an inadvertent swapping of genomic material that occurs when two viruses happen to invade the same cell, and their progeny are assembled with bits and pieces of RNA belonging to the other. Beta-coronaviruses will only combine with other beta-coronaviruses but can acquire, by recombination, almost any genetic element present in the collective genomic pool. What they cannot acquire is an element the pool does not possess. And no known SARS-related beta-coronavirus, the class to which SARS2 belongs, possesses a furin cleavage site.

Proponents of natural emergence say SARS2 could have picked up the site from some as yet unknown beta-coronavirus. But bat SARS-related beta-coronaviruses evidently don’t need a furin cleavage site to infect bat cells, so there’s no great likelihood that any in fact possesses one, and indeed none has been found so far.

The proponents’ next argument is that SARS2 acquired its furin cleavage site from people. A predecessor of SARS2 could have been circulating in the human population for months or years until at some point it acquired a furin cleavage site from human cells. It would then have been ready to break out as a pandemic.

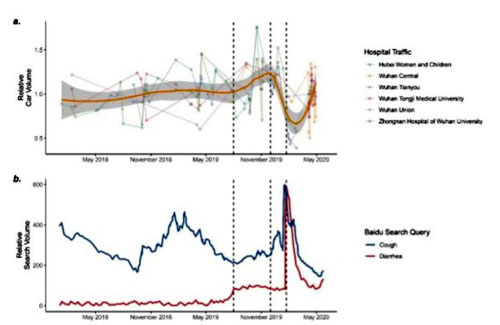

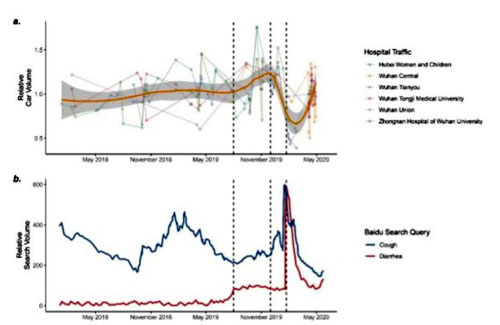

If this is what happened, there should be traces in hospital surveillance records of the people infected by the slowly evolving virus. But none has so far come to light. According to the WHO report on the origins of the virus, the sentinel hospitals in Hubei province, home of Wuhan, routinely monitor influenza-like illnesses and “no evidence to suggest substantial SARSCoV-2 transmission in the months preceding the outbreak in December was observed.”

So it’s hard to explain how the SARS2 virus picked up its furin cleavage site naturally, whether by mutation or recombination.

That leaves a gain-of-function experiment. For those who think SARS2 may have escaped from a lab, explaining the furin cleavage site is no problem at all. “Since 1992 the virology community has known that the one sure way to make a virus deadlier is to give it a furin cleavage site at the S1/S2 junction in the laboratory,” writes Steven Quay, a biotech entrepreneur interested in the origins of SARS2. “At least 11 gain-of-function experiments, adding a furin site to make a virus more infective, are published in the open literature, including [by] Dr. Zhengli Shi, head of coronavirus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.”

4) A question of codons. There’s another aspect of the furin cleavage site that narrows the path for a natural emergence origin even further.

As everyone knows (or may at least recall from high school), the genetic code uses three units of DNA to specify each amino acid unit of a protein chain. When read in groups of 3, the 4 different kinds of DNA unit can specify 4 x 4 x 4 or 64 different triplets, or codons as they are called. Since there are only 20 kinds of amino acid, there are more than enough codons to go around, allowing some amino acids to be specified by more than one codon. The amino acid arginine, for instance, can be designated by any of the six codons CGU, CGC, CGA, CGG, AGA or AGG, where A, U, G and C stand for the four different kinds of unit in RNA.

Here’s where it gets interesting. Different organisms have different codon preferences. Human cells like to designate arginine with the codons CGT, CGC or CGG. But CGG is coronavirus’s least popular codon for arginine. Keep that in mind when looking at how the amino acids in the furin cleavage site are encoded in the SARS2 genome.

Now the functional reason why SARS2 has a furin cleavage site, and its cousin viruses don’t, can be seen by lining up (in a computer) the string of nearly 30,000 nucleotides in its genome with those of its cousin coronaviruses, of which the closest so far known is one called RaTG13. Compared with RaTG13, SARS2 has a 12-nucleotide insert right at the S1/S2 junction. The insert is the sequence T-CCT-CGG-CGG-GC. The CCT codes for proline, the two CGG’s for two arginines, and the GC is the beginning of a GCA codon that codes for alanine.

There are several curious features about this insert but the oddest is that of the two side-by-side CGG codons. Only 5 percent of SARS2’s arginine codons are CGG, and the double codon CGG-CGG has not been found in any other beta-coronavirus. So how did SARS2 acquire a pair of arginine codons that are favored by human cells but not by coronaviruses?

Proponents of natural emergence have an up-hill task to explain all the features of SARS2’s furin cleavage site. They have to postulate a recombination event at a site on the virus’s genome where recombinations are rare, and the insertion of a 12-nucleotide sequence with a double arginine codon unknown in the beta-coronavirus repertoire, at the only site in the genome that would significantly expand the virus’s infectivity.

“Yes, but your wording makes this sound unlikely — viruses are specialists at unusual events,” is the riposte of David L. Robertson, a virologist at the University of Glasgow who regards lab escape as a conspiracy theory. “Recombination is naturally very, very frequent in these viruses, there are recombination breakpoints in the spike protein and these codons appear unusual exactly because we’ve not sampled enough.”

Robertson is correct that evolution is always producing results that may seem unlikely but in fact are not. Viruses can generate untold numbers of variants but we see only the one-in-a-billion that natural selection picks for survival. But this argument could be pushed too far. For instance, any result of a gain-of-function experiment could be explained as one that evolution would have arrived at in time. And the numbers game can be played the other way. For the furin cleavage site to arise naturally in SARS2, a chain of events has to happen, each of which is quite unlikely for the reasons given above. A long chain with several improbable steps is unlikely to ever be completed.

For the lab escape scenario, the double CGG codon is no surprise. The human-preferred codon is routinely used in labs. So anyone who wanted to insert a furin cleavage site into the virus’s genome would synthesize the PRRA-making sequence in the lab and would be likely to use CGG codons to do so.

“When I first saw the furin cleavage site in the viral sequence, with its arginine codons, I said to my wife it was the smoking gun for the origin of the virus,” said David Baltimore, an eminent virologist and former president of CalTech. “These features make a powerful challenge to the idea of a natural origin for SARS2,” he said. [1]

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36135

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: U.S. government gave $3.7 million grant to Wuhan lab at

Part 2 of 2

A third scenario of origin.

There’s a variation on the natural emergence scenario that’s worth considering. This is the idea that SARS2 jumped directly from bats to humans, without going through an intermediate host as SARS1 and MERS did. A leading advocate is the virologist David Robertson who notes that SARS2 can attack several other species besides humans. He believes the virus evolved a generalist capability while still in bats. Because the bats it infects are widely distributed in southern and central China, the virus had ample opportunity to jump to people, even though it seems to have done so on only one known occasion. Robertson’s thesis explains why no one has so far found a trace of SARS2 in any intermediate host or in human populations surveilled before December 2019. It would also explain the puzzling fact that SARS2 has not changed since it first appeared in humans — it didn’t need to because it could already attack human cells efficiently.

One problem with this idea, though, is that if SARS2 jumped from bats to people in a single leap and hasn’t changed much since, it should still be good at infecting bats. And it seems it isn’t.

“Tested bat species are poorly infected by SARS-CoV-2 and they are therefore unlikely to be the direct source for human infection,” write a scientific group skeptical of natural emergence.

Still, Robertson may be onto something. The bat coronaviruses of the Yunnan caves can infect people directly. In April 2012 six miners clearing bat guano from the Mojiang mine contracted severe pneumonia with COVID-19-like symptoms and three eventually died. A virus isolated from the Mojiang mine, called RaTG13, is still the closest known relative of SARS2. Much mystery surrounds the origin, reporting and strangely low affinity of RaTG13 for bat cells, as well as the nature of 8 similar viruses that Shi reports she collected at the same time but has not yet published despite their great relevance to the ancestry of SARS2. But all that is a story for another time. The point here is that bat viruses can infect people directly, though only in special conditions.

So who else, besides miners excavating bat guano, comes into particularly close contact with bat coronaviruses? Well, coronavirus researchers do. Shi says she and her group collected more than 1,300 bat samples during some eight visits to the Mojiang cave between 2012 and 2015, and there were doubtless many expeditions to other Yunnan caves.

Imagine the researchers making frequent trips from Wuhan to Yunnan and back, stirring up bat guano in dark caves and mines, and now you begin to see a possible missing link between the two places. Researchers could have gotten infected during their collecting trips, or while working with the new viruses at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The virus that escaped from the lab would have been a natural virus, not one cooked up by gain of function.

The direct-from-bats thesis is a chimera between the natural emergence and lab escape scenarios. It’s a possibility that can’t be dismissed. But against it are the facts that 1) both SARS2 and RaTG13 seem to have only feeble affinity for bat cells, so one can’t be fully confident that either ever saw the inside of a bat; and 2) the theory is no better than the natural emergence scenario at explaining how SARS2 gained its furin cleavage site, or why the furin cleavage site is determined by human-preferred arginine codons instead of by the bat-preferred codons.

Where we are so far. Neither the natural emergence nor the lab escape hypothesis can yet be ruled out. There is still no direct evidence for either. So no definitive conclusion can be reached.

That said, the available evidence leans more strongly in one direction than the other. Readers will form their own opinion. But it seems to me that proponents of lab escape can explain all the available facts about SARS2 considerably more easily than can those who favor natural emergence.