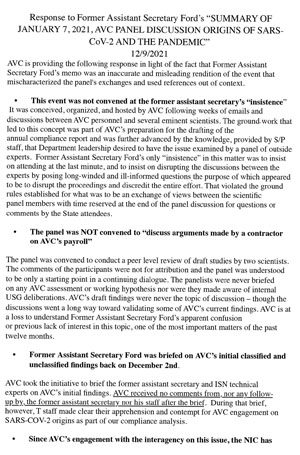

The Lab-Leak Theory: Inside the Fight to Uncover COVID-19’s Origins: Throughout 2020, the notion that the novel coronavirus leaked from a lab was off-limits. Those who dared to push for transparency say toxic politics and hidden agendas kept us in the dark.

by Katherine Eban

Vanity Fair

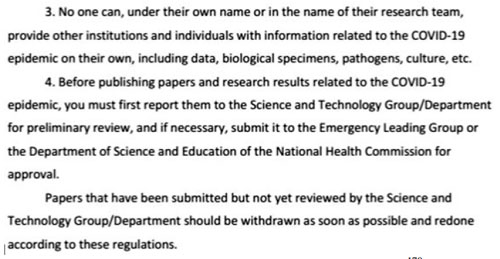

JUNE 3, 2021

I. A Group Called DRASTIC

Gilles Demaneuf is a data scientist with the Bank of New Zealand in Auckland. He was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome ten years ago, and believes it gives him a professional advantage. “I’m very good at finding patterns in data, when other people see nothing,” he says.

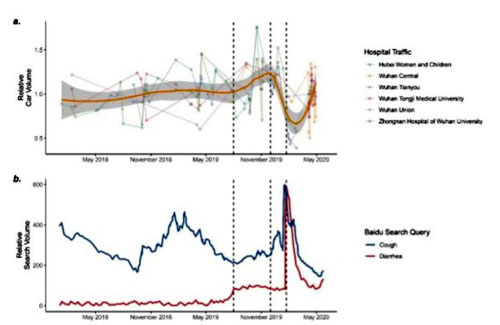

Early last spring, as cities worldwide were shutting down to halt the spread of COVID-19, Demaneuf, 52, began reading up on the origins of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease. The prevailing theory was that it had jumped from bats to some other species before making the leap to humans at a market in China, where some of the earliest cases appeared in late 2019. The Huanan wholesale market, in the city of Wuhan, is a complex of markets selling seafood, meat, fruit, and vegetables. A handful of vendors sold live wild animals—a possible source of the virus.

That wasn’t the only theory, though. Wuhan is also home to China’s foremost coronavirus research laboratory, housing one of the world’s largest collections of bat samples and bat-virus strains. The Wuhan Institute of Virology’s lead coronavirus researcher, Shi Zhengli, was among the first to identify horseshoe bats as the natural reservoirs for SARS-CoV, the virus that sparked an outbreak in 2002, killing 774 people and sickening more than 8,000 globally. After SARS, bats became a major subject of study for virologists around the world, and Shi became known in China as “Bat Woman” for her fearless exploration of their caves to collect samples. More recently, Shi and her colleagues at the WIV have performed high-profile experiments that made pathogens more infectious. Such research, known as “gain-of-function,” has generated heated controversy among virologists.

To some people, it seemed natural to ask whether the virus causing the global pandemic had somehow leaked from one of the WIV’s labs—a possibility Shi has strenuously denied.

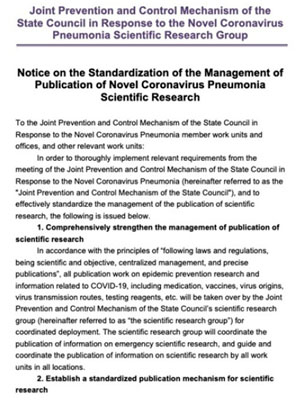

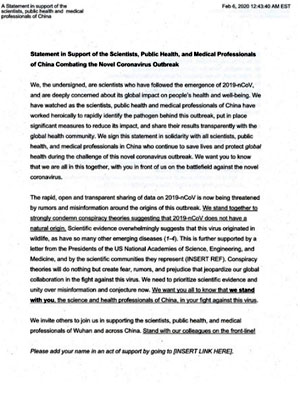

On February 19, 2020, The Lancet, among the most respected and influential medical journals in the world, published a statement that roundly rejected the lab-leak hypothesis, effectively casting it as a xenophobic cousin to climate change denialism and anti-vaxxism. Signed by 27 scientists, the statement expressed “solidarity with all scientists and health professionals in China” and asserted: “We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin.”

The Lancet statement effectively ended the debate over COVID-19’s origins before it began. To Gilles Demaneuf, following along from the sidelines, it was as if it had been “nailed to the church doors,” establishing the natural origin theory as orthodoxy. “Everyone had to follow it. Everyone was intimidated. That set the tone.”

The statement struck Demaneuf as “totally nonscientific.” To him, it seemed to contain no evidence or information. And so he decided to begin his own inquiry in a “proper” way, with no idea of what he would find.

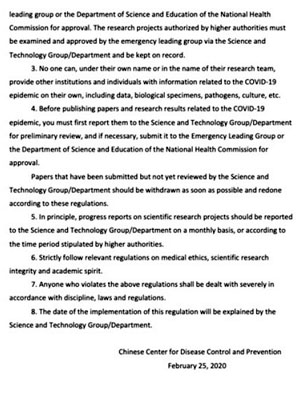

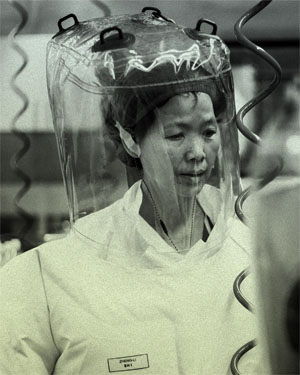

Shi Zhengli, the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s lead coronavirus researcher, is frequently pictured in a full-body positive-pressure suit, though not all the labs there require one. BY JOHANNES EISELE/AFP/GETTY IMAGES.

Demaneuf began searching for patterns in the available data, and it wasn’t long before he spotted one. China’s laboratories were said to be airtight, with safety practices equivalent to those in the U.S. and other developed countries. But Demaneuf soon discovered that there had been four incidents of SARS-related lab breaches since 2004, two occurring at a top laboratory in Beijing. Due to overcrowding there, a live SARS virus that had been improperly deactivated, had been moved to a refrigerator in a corridor. A graduate student then examined it in the electron microscope room and sparked an outbreak.

Demaneuf published his findings in a Medium post, titled “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: a review of SARS Lab Escapes.” By then, he had begun working with another armchair investigator, Rodolphe de Maistre. A laboratory project director based in Paris who had previously studied and worked in China, de Maistre was busy debunking the notion that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was a “laboratory” at all. In fact, the WIV housed numerous laboratories that worked on coronaviruses. Only one of them has the highest biosafety protocol: BSL-4, in which researchers must wear full-body pressurized suits with independent oxygen. Others are designated BSL-3 and even BSL-2, roughly as secure as an American dentist’s office.

Having connected online, Demaneuf and de Maistre began assembling a comprehensive list of research laboratories in China. As they posted their findings on Twitter, they were soon joined by others around the world. Some were cutting-edge scientists at prestigious research institutes. Others were science enthusiasts. Together, they formed a group called DRASTIC, short for Decentralized Radical Autonomous Search Team Investigating COVID-19. Their stated objective was to solve the riddle of COVID-19’s origin.

State Department investigators say they were repeatedly advised not to open a “Pandora’s box.”

At times, it seemed the only other people entertaining the lab-leak theory were crackpots or political hacks hoping to wield COVID-19 as a cudgel against China. President Donald Trump’s former political adviser Steve Bannon, for instance, joined forces with an exiled Chinese billionaire named Guo Wengui to fuel claims that China had developed the disease as a bioweapon and purposefully unleashed it on the world. As proof, they paraded a Hong Kong scientist around right-wing media outlets until her manifest lack of expertise doomed the charade.

With disreputable wing nuts on one side of them and scornful experts on the other, the DRASTIC researchers often felt as if they were on their own in the wilderness, working on the world’s most urgent mystery. They weren’t alone. But investigators inside the U.S. government asking similar questions were operating in an environment that was as politicized and hostile to open inquiry as any Twitter echo chamber. When Trump himself floated the lab-leak hypothesis last April, his divisiveness and lack of credibility made things more, not less, challenging for those seeking the truth.

“The DRASTIC people are doing better research than the U.S. government,” says David Asher, a former senior investigator under contract to the State Department.

The question is: Why?

II. “A Can of Worms”

Since December 1, 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 has infected more than 170 million people around the world and killed more than 3.5 million. To this day, we don’t know how or why this novel coronavirus suddenly appeared in the human population. Answering that question is more than an academic pursuit: Without knowing where it came from, we can’t be sure we’re taking the right steps to prevent a recurrence.

And yet, in the wake of the Lancet statement and under the cloud of Donald Trump’s toxic racism, which contributed to an alarming wave of anti-Asian violence in the U.S., one possible answer to this all-important question remained largely off-limits until the spring of 2021.

Behind closed doors, however, national security and public health experts and officials across a range of departments in the executive branch were locked in high-stakes battles over what could and couldn’t be investigated and made public.

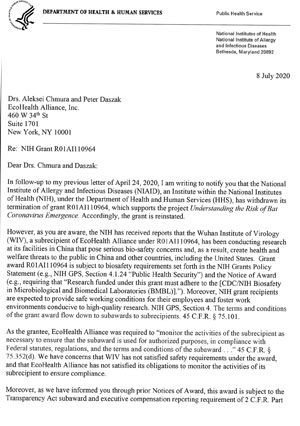

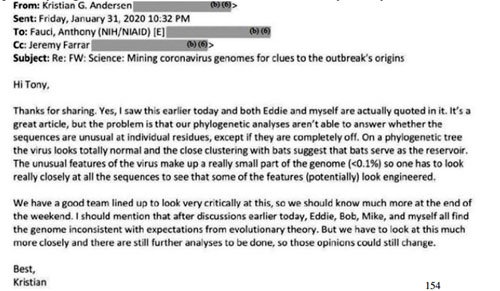

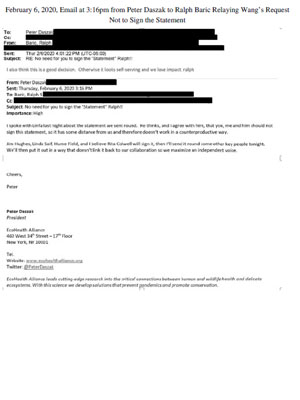

A months long Vanity Fair investigation, interviews with more than 40 people, and a review of hundreds of pages of U.S. government documents, including internal memos, meeting minutes, and email correspondence, found that conflicts of interest, stemming in part from large government grants supporting controversial virology research, hampered the U.S. investigation into COVID-19’s origin at every step. In one State Department meeting, officials seeking to demand transparency from the Chinese government say they were explicitly told by colleagues not to explore the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s gain-of-function research, because it would bring unwelcome attention to U.S. government funding of it.

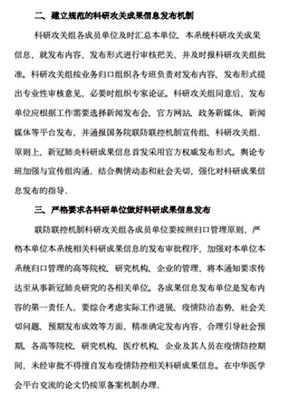

In an internal memo obtained by Vanity Fair, Thomas DiNanno, former acting assistant secretary of the State Department’s Bureau of Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance, wrote that staff from two bureaus, his own and the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, “warned” leaders within his bureau “not to pursue an investigation into the origin of COVID-19” because it would “‘open a can of worms’ if it continued.”

There are reasons to doubt the lab-leak hypothesis. There is a long, well-documented history of natural spillovers leading to outbreaks, even when the initial and intermediate host animals have remained a mystery for months and years, and some expert virologists say the supposed oddities of the SARS-CoV-2 sequence have been found in nature.

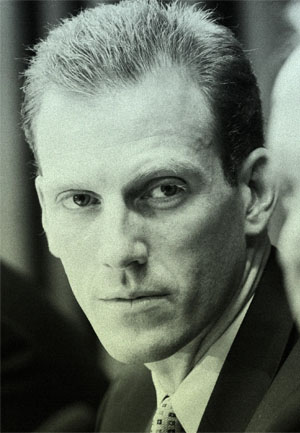

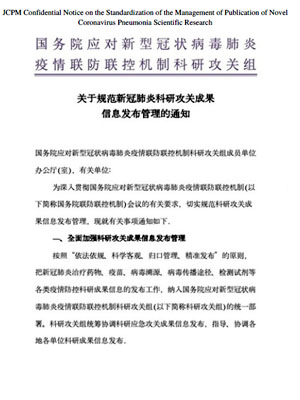

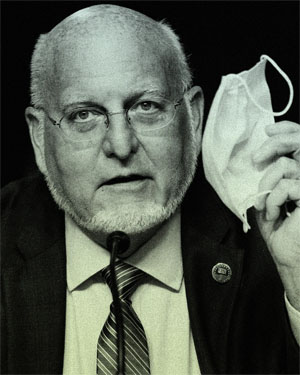

Dr. Robert Redfield, former director of the CDC, said he received death threats from fellow scientists after telling CNN he thought the virus likely escaped from a lab. “I expected it from politicians. I didn’t expect it from science,” he said. BY ANDREW HARNIK/GETTY IMAGES

But for most of the past year, the lab-leak scenario was treated not simply as unlikely or even inaccurate but as morally out-of-bounds. In late March, former Centers for Disease Control director Robert Redfield received death threats from fellow scientists after telling CNN that he believed COVID-19 had originated in a lab. “I was threatened and ostracized because I proposed another hypothesis,” Redfield told Vanity Fair. “I expected it from politicians. I didn’t expect it from science.”

With President Trump out of office, it should be possible to reject his xenophobic agenda and still ask why, in all places in the world, did the outbreak begin in the city with a laboratory housing one of the world’s most extensive collection of bat viruses, doing some of the most aggressive research?

Dr. Richard Ebright, board of governors professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Rutgers University, said that from the very first reports of a novel bat-related coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, it took him “a nanosecond or a picosecond” to consider a link to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Only two other labs in the world, in Galveston, Texas, and Chapel Hill, North Carolina, were doing similar research. “It’s not a dozen cities,” he said. “It’s three places.”

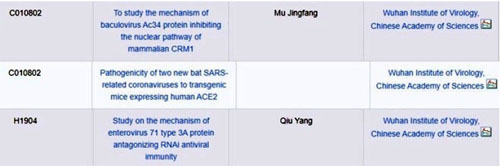

Then came the revelation that the Lancet statement was not only signed but organized by a zoologist named Peter Daszak, who has repackaged U.S. government grants and allocated them to facilities conducting gain-of-function research—among them the WIV itself. David Asher, now a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, ran the State Department’s day-to-day COVID-19 origins inquiry. He said it soon became clear that “there is a huge gain-of-function bureaucracy” inside the federal government.

As months go by without a host animal that proves the natural theory, the questions from credible doubters have gained in urgency. To one former federal health official, the situation boiled down to this: An institute “funded by American dollars is trying to teach a bat virus to infect human cells, then there is a virus” in the same city as that lab. It is “not being intellectually honest not to consider the hypothesis” of a lab escape.

And given how aggressively China blocked efforts at a transparent investigation, and in light of its government’s own history of lying, obfuscating, and crushing dissent, it’s fair to ask if Shi Zhengli, the Wuhan Institute’s lead coronavirus researcher, would be at liberty to report a leak from her lab even if she’d wanted to.

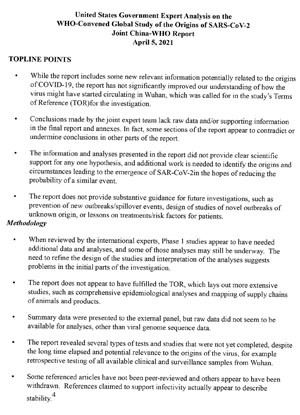

On May 26, the steady crescendo of questions led President Joe Biden to release a statement acknowledging that the intelligence community had “coalesced around two likely scenarios,” and announce that he had asked for a more definitive conclusion within 90 days. His statement noted, “The failure to get our inspectors on the ground in those early months will always hamper any investigation into the origin of COVID-19.” But that wasn’t the only failure.

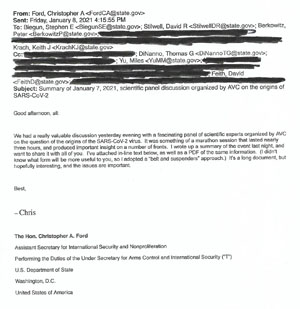

In the words of David Feith, former deputy assistant secretary of state in the East Asia bureau, “The story of why parts of the U.S. government were not as curious as many of us think they should have been is a hugely important one.”

III. “Smelled Like a Cover-Up”

On December 9, 2020, roughly a dozen State Department employees from four different bureaus gathered in a conference room in Foggy Bottom to discuss an upcoming fact-finding mission to Wuhan organized in part by the World Health Organization. The group agreed on the need to press China to allow a thorough, credible, and transparent investigation, with unfettered access to markets, hospitals, and government laboratories. The conversation then turned to the more sensitive question: What should the U.S. government say publicly about the Wuhan Institute of Virology?

A small group within the State Department’s Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance bureau had been studying the Institute for months. The group had recently acquired classified intelligence suggesting that three WIV researchers conducting gain-of-function experiments on coronavirus samples had fallen ill in the autumn of 2019, before the COVID-19 outbreak was known to have started.

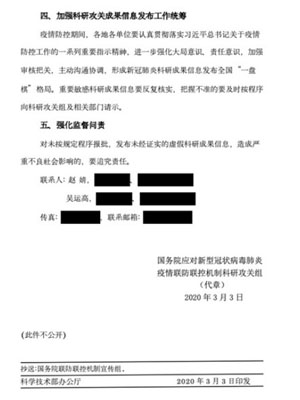

As officials at the meeting discussed what they could share with the public, they were advised by Christopher Park, the director of the State Department’s Biological Policy Staff in the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, not to say anything that would point to the U.S. government’s own role in gain-of-function research, according to documentation of the meeting obtained by Vanity Fair.

Only two other labs in the world, in Texas and North Carolina, were doing similar research. “It’s not a dozen cities,” Dr. Richard Ebright said. “It’s three places.”

Some of the attendees were “absolutely floored,” said an official familiar with the proceedings. That someone in the U.S. government could “make an argument that is so nakedly against transparency, in light of the unfolding catastrophe, was…shocking and disturbing.”

Park, who in 2017 had been involved in lifting a U.S. government moratorium on funding for gain-of-function research, was not the only official to warn the State Department investigators against digging in sensitive places. As the group probed the lab-leak scenario, among other possibilities, its members were repeatedly advised not to open a “Pandora’s box,” said four former State Department officials interviewed by Vanity Fair. The admonitions “smelled like a cover-up,” said Thomas DiNanno, “and I wasn’t going to be part of it.”

Reached for comment, Chris Park told Vanity Fair, “I am skeptical that people genuinely felt they were being discouraged from presenting facts.” He added that he was simply arguing that it “is making an enormous and unjustifiable leap…to suggest that research of that kind [meant] that something untoward is going on.”

IV. An “Antibody Response”

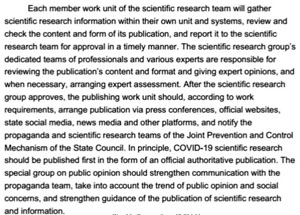

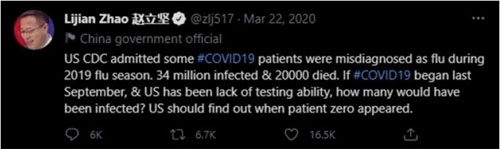

There were two main teams inside the U.S. government working to uncover the origins of COVID-19: one in the State Department and another under the direction of the National Security Council. No one at the State Department had much interest in Wuhan’s laboratories at the start of the pandemic, but they were gravely concerned with China’s apparent cover-up of the outbreak’s severity. The government had shut down the Huanan market, ordered laboratory samples destroyed, claimed the right to review any scientific research about COVID-19 ahead of publication, and expelled a team of Wall Street Journal reporters.

In January 2020, a Wuhan ophthalmologist named Li Wenliang, who’d tried to warn his colleagues that the pneumonia could be a form of SARS was arrested, accused of disrupting the social order, and forced to write a self-criticism. He died of COVID-19 in February, lionized by the Chinese public as a hero and whistleblower.

“You had Chinese [government] coercion and suppression,” said David Feith of the State Department’s East Asia bureau. “We were very concerned that they were covering it up and whether the information coming to the World Health Organization was reliable.”

As questions swirled, Miles Yu, the State Department’s principal China strategist, noted that the WIV had remained largely silent. Yu, who is fluent in Mandarin, began mirroring its website and compiling a dossier of questions about its research. In April, he gave his dossier to Secretary of State Pompeo, who in turn publicly demanded access to the laboratories there.

It is not clear whether Yu’s dossier made its way to President Trump. But on April 30, 2020, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence put out an ambiguous statement whose apparent goal was to suppress a growing furor around the lab-leak theory. It said that the intelligence community “concurs with the wide scientific consensus that the COVID-19 virus was not manmade or genetically modified” but would continue to assess “whether the outbreak began through contact with infected animals or if it was the result of an accident at a laboratory in Wuhan.”

State Department official Thomas DiNanno wrote a memo charging that staff from his bureau were “warned…not to pursue an investigation into the origin of COVID-19” because it would “‘open a can of worms’ if it continued.” SOURCE: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE

“It was pure panic,” said former deputy national security adviser Matthew Pottinger. “They were getting flooded with queries. Someone made the unfortunate decision to say, ‘We basically know nothing, so let’s put out the statement.’”

Then, the bomb-thrower-in-chief weighed in. At a press briefing just hours later, Trump contradicted his own intelligence officials and claimed that he had seen classified information indicating that the virus had come from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Asked what the evidence was, he said, “I can’t tell you that. I’m not allowed to tell you that.”

Trump’s premature statement poisoned the waters for anyone seeking an honest answer to the question of where COVID-19 came from. According to Pottinger, there was an “antibody response” within the government, in which any discussion of a possible lab origin was linked to destructive nativist posturing.

The revulsion extended to the international science community, whose “maddening silence” frustrated Miles Yu. He recalled, “Anyone who dares speak out would be ostracized.”

V. “Too Risky to Pursue”

The idea of a lab leak first came to NSC officials not from hawkish Trumpists but from Chinese social media users, who began sharing their suspicions as early as January 2020. Then, in February, a research paper coauthored by two Chinese scientists, based at separate Wuhan universities, appeared online as a preprint. It tackled a fundamental question: How did a novel bat coronavirus get to a major metropolis of 11 million people in central China, in the dead of winter when most bats were hibernating, and turn a market where bats weren’t sold into the epicenter of an outbreak?

The paper offered an answer: “We screened the area around the seafood market and identified two laboratories conducting research on bat coronavirus.” The first was the Wuhan Center for Disease Control and Prevention, which sat just 280 meters from the Huanan market and had been known to collect hundreds of bat samples. The second, the researchers wrote, was the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

The paper came to a staggeringly blunt conclusion about COVID-19: “the killer coronavirus probably originated from a laboratory in Wuhan.... Regulations may be taken to relocate these laboratories far away from city center and other densely populated places.” Almost as soon as the paper appeared on the internet, it disappeared, but not before U.S. government officials took note.[/b]

By then, Matthew Pottinger had approved a COVID-19 origins team, run by the NSC directorate that oversaw issues related to weapons of mass destruction. A longtime Asia expert and former journalist, Pottinger purposefully kept the team small, because there were so many people within the government “wholly discounting the possibility of a lab leak, who were predisposed that it was impossible,” said Pottinger. In addition, many leading experts had either received or approved funding for gain-of-function research. Their “conflicted” status, said Pottinger, “played a profound role in muddying the waters and contaminating the shot at having an impartial inquiry.”

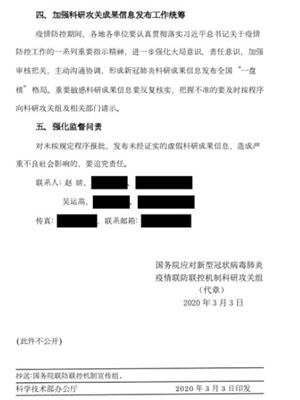

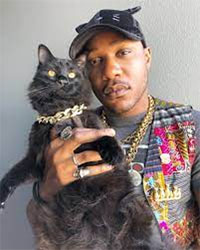

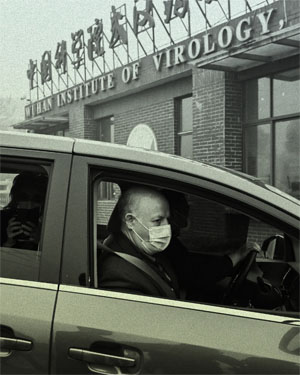

Peter Daszak, who repackaged U.S. government grants and allocated the funds to research institutes including the WIV, arrives there on February 3, 2021, during a fact-finding mission organized in part by the World Health Organization. BY HECTOR RETAMAL/AFP/GETTY IMAGES.

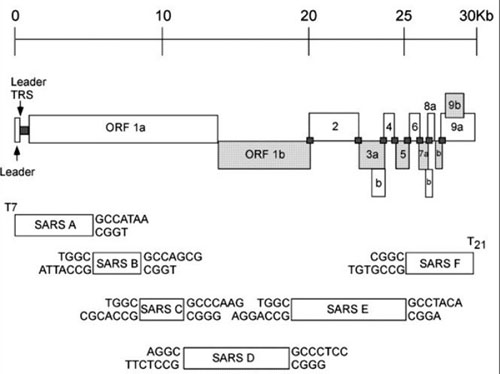

As they combed open sources as well as classified information, the team’s members soon stumbled on a 2015 research paper by Shi Zhengli and the University of North Carolina epidemiologist Ralph Baric proving that the spike protein of a novel coronavirus could infect human cells. Using mice as subjects, they inserted the protein from a Chinese rufous horseshoe bat into the molecular structure of the SARS virus from 2002, creating a new, infectious pathogen.

This gain-of-function experiment was so fraught that the authors flagged the danger themselves, writing, “scientific review panels may deem similar studies…too risky to pursue.” In fact, the study was intended to raise an alarm and warn the world of “a potential risk of SARS-CoV re-emergence from viruses currently circulating in bat populations.” The paper’s acknowledgments cited funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and from a nonprofit called EcoHealth Alliance, which had parceled out grant money from the U.S. Agency for International Development. EcoHealth Alliance is run by Peter Daszak, the zoologist who helped organize the Lancet statement.

That a genetically engineered virus might have escaped from the WIV was one alarming scenario. But it was also possible that a research trip to collect bat samples could have led to infection in the field, or back at the lab.

The NSC investigators found ready evidence that China’s labs were not as safe as advertised. Shi Zhengli herself had publicly acknowledged that, until the pandemic, all of her team’s coronavirus research—some involving live SARS-like viruses—had been conducted in less secure BSL-3 and even BSL-2 laboratories.

In 2018, a delegation of American diplomats visited the WIV for the opening of its BSL-4 laboratory, a major event. In an unclassified cable, as a Washington Post columnist reported, they wrote that a shortage of highly trained technicians and clear protocols threatened the facility’s safe operations. The issues had not stopped the WIV’s leadership from declaring the lab “ready for research on class-four pathogens (P4), among which are the most virulent viruses that pose a high risk of aerosolized person-to-person transmission.”

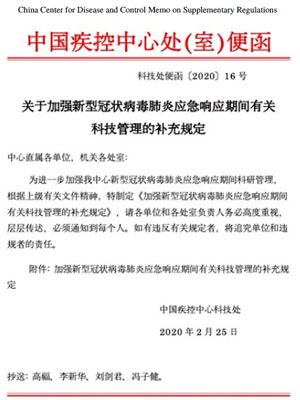

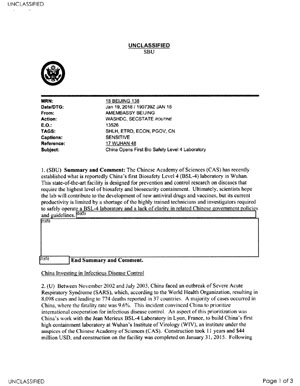

Memo

MRN: 18 BEIJING 138

Date/DTG: Jan 19, 2018 / 190739Z Jan 18

From: AMEMBASSY BEIJING

Action: WASHDC, SECSTATE ROUTINE

E.O.: 13526

TAGS: SHLH, ETRD, ECON, PGOV, CN

Captions: SENSITIVE

Reference: 17 WUHAN 48

Subject: China Opens First Bio Safety Level 4 Laboratory

1. (SBU) Summary and Comment: The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) has recently established what is reportedly China's first Biosafety Level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory in Wuhan. This state-of-the-art facility is designed for prevention and control research on diseases that require the highest level of biosafety and biosecurity containment. Ultimately, scientists hope the lab will contribute to the development of new antiviral drugs and vaccines, but its current productivity is limited by a shortage of the highly trained technicians and investigators required to safely operate a BSL-4 laboratory and a lack of clarity in related Chinese government policies and guidelines. (b)(5) [DELETE] (b)(5) (b)(5) End Summary and Comment.

China Investing in Infectious Disease Control

2. (U) Between November 2002 and July 2003, China faced an outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which, according to the World Health Organization, resulting in 8,098 cases and leading to 774 deaths reported in 37 countries. A majority of cases occurred in China, where the fatality rate was 9.6%. This incident convinced China to prioritize international cooperation for infectious disease control. An aspect of this prioritization was China's work with the Jean Merieux BSL-4 Laboratory in Lyon, France, to build China's first high containment laboratory at Wuhan's Institute of Virology (WIV), an institute under the auspices of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). Construction took 11 years and $44 million USD. and construction on the facility was completed on January 31, 2015. Following two years of effort, which is not unusual for such facilities, the WIV lab was accredited in February 2017 by the China National Accreditation Service for Conformity Assessment. It occupies four floors and consists of over 32,000 square feet. WIV leadership now considers the lab operational and ready for research on class-four pathogens (P4), among which are the most virulent viruses that pose a high risk of aerosolized person-to-person transmission.

Unclear Guidelines on Virus Access and a Lack of Trained Talent Impede Research

3. (SBU) In addition to accreditation, the lab must also receive permission from the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) to initiate research on specific highly contagious pathogens. According to some WIV scientists, it is unclear how NHFPC determines what viruses can or cannot be studied in the new laboratory. To date, WIV has obtained permission for research on three viruses: Ebola virus, Nipah virus, and Xinjiang hemorrhagic fever virus (a strain of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever found in China's Xinjiang Province). Despite this permission, however, the Chinese government has not allowed the WIV to import Ebola viruses for study in the BSL-4 lab. Therefore, WIV scientists are frustrated and have pointed out that they won't be able to conduct research project with Ebola viruses at the new BSL-4 lab despite of the permission.

(b)(6) [DELETE]

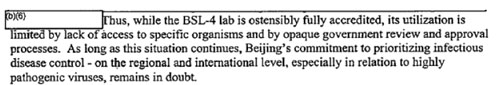

(b)(6) Thus, while the BSL-4 lab is ostensibly fully accredited, its utilization is limited by lack of access to specific organisms and by opaque government review and approval processes. As long as this situation continues, Beijing's commitment to prioritizing infectious disease control -- on the regional and international level, especially in relation to highly pathogenic viruses, remains in doubt.

(b)(6) [DELETE] noted that the new lab has a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory. University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston (UTMB), which has one of several well-established BSL-4 labs in the United States (supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID of NIH)), has scientific collaborations with WIV, which may help alleviate this talent gap over time. Reportedly, researchers from TMB are helping train technicians who work in the WIV BSL-4 lab. Despite this (b)(6) [DELETE] they would welcome more help from U.S. and international organizations as they establish "gold standard" operating procedures and training courses for the first time in China. As China is building more BSL-4 labs, including one in Harbin Veterinary Research Institute subordinated to the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS) for veterinary research use (b)(6) [DELETE] the training for technicians and investigators working on dangerous pathogens will certainly be in demand.

Despite Limitations. WIV Researchers Produce SARS Discoveries

6. (SBU) The ability of WIV scientists to undertake productive research despite limitations on the use of the new BSL-4 facility is demonstrated by a recent publication on the origins of SARS. Over a five-year study, (b)(6) [DELETE] (and their research team) widely sampled bats in Yunnan province with funding support from NIAID/NIH, USAID, and several Chinese funding agencies. The study results were published in PLoS Pathogens online on Nov. 30, 2017 (1), and it demonstrated that a SARS-like corona viruses isolated from horseshoe bats in a single cave contain all the building blocks of the pandemic SARS-coronavirus genome that caused the human outbreak. These results strongly suggest that the highly pathogenic SARS-coronavirus originated in this bat population. Most importantly, the researchers also showed that various SARS-like coronaviruses can interact with ACE2, the human receptor identified for SARS-coronavirus. This finding strongly suggests that SARS-like coronaviruses from bats can be transmitted to humans to cause SARS-like disease. From a public health perspective, this makes the continued surveillance of SARS-like coronaviruses in bats and study of the animal-human interface critical to future emerging corona virus outbreak prediction and prevention (b)(5) [DELETE] (b)(5) WIV scientists are allowed to study the SARS-like coronaviruses isolated from bats while they are precluded from studying human-disease causing SARS coronavirus in their new BSL-4 lab until permission for such work is granted by the NHFCP.

1. Hu B, Zeng L-P, Yang X-L, Ge X-Y, Zhang W, Li B, et a1. (2017) Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog 13(11): e1006698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698

Signature: BRANSTAD

Drafted By: (b)(6) [DELETE]

Cleared By: (b)(6) [DELETE]

Approved By: (b)(6) [DELETE]

Released By: (b)(6) [DELETE]

Info: CHINA POSTS COLLECTIVE ROUTINE

Dissemination Rule: Archive Copy

UNCLASSIFIED

SBU

On February 14, 2020, to the surprise of NSC officials, President Xi Jinping of China announced a plan to fast-track a new biosecurity law to tighten safety procedures throughout the country’s laboratories. Was this a response to confidential information? “In the early weeks of the pandemic, it didn’t seem crazy to wonder if this thing came out of a lab,” Pottinger reflected.

Apparently, it didn’t seem crazy to Shi Zhengli either. A Scientific American article first published in March 2020, for which she was interviewed, described how her lab had been the first to sequence the virus in those terrible first weeks. It also recounted how:

[S]he frantically went through her own lab’s records from the past few years to check for any mishandling of experimental materials, especially during disposal. Shi breathed a sigh of relief when the results came back: none of the sequences matched those of the viruses her team had sampled from bat caves. “That really took a load off my mind,” she says. “I had not slept a wink for days.”

As the NSC tracked these disparate clues, U.S. government virologists advising them flagged one study first submitted in April 2020. Eleven of its 23 coauthors worked for the Academy of Military Medical Sciences, the Chinese army’s medical research institute. Using the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR, the researchers had engineered mice with humanized lungs, then studied their susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. As the NSC officials worked backward from the date of publication to establish a timeline for the study, it became clear that the mice had been engineered sometime in the summer of 2019, before the pandemic even started. The NSC officials were left wondering: Had the Chinese military been running viruses through humanized mouse models, to see which might be infectious to humans?

Believing they had uncovered important evidence in favor of the lab-leak hypothesis, the NSC investigators began reaching out to other agencies. That’s when the hammer came down. “We were dismissed,” said Anthony Ruggiero, the NSC’s senior director for counterproliferation and biodefense. “The response was very negative.”

VI. Sticklers for Accuracy

By the summer of 2020, Gilles Demaneuf was spending up to four hours a day researching the origins of COVID-19, joining Zoom meetings before dawn with European collaborators and not sleeping much. He began to receive anonymous calls and notice strange activity on his computer, which he attributed to Chinese government surveillance. “We are being monitored for sure,” he says. He moved his work to the encrypted platforms Signal and ProtonMail.

As they posted their findings, the DRASTIC researchers attracted new allies. Among the most prominent was Jamie Metzl, who launched a blog on April 16 that became a go-to site for government researchers and journalists examining the lab-leak hypothesis. A former executive vice president of the Asia Society, Metzl sits on the World Health Organization’s advisory committee on human genome editing and served in the Clinton administration as the NSC’s director for multilateral affairs. In his first post on the subject, he made clear that he had no definitive proof and believed that Chinese researchers at the WIV had the “best intentions.” Metzl also noted, “In no way do I seek to support or align myself with any activities that may be considered unfair, dishonest, nationalistic, racist, bigoted, or biased in any way.”

Blocking pro-democracy activist from attending event

Pro-democracy activist and secretary-general of Demosisto Joshua Wong was allegedly disallowed by Asia Society Hong Kong from speaking at a book launch originally scheduled to take place at its Hong Kong venue on June 28, 2017. It was understood that Asia Society Hong Kong was approached by PEN Hong Kong to co-curate the book launch, but negotiations stalled upon the former's request for a more diverse panel of speakers. PEN Hong Kong, a non-profit organization supporting literature and freedom of expression, eventually decided to relocate the launch of Hong Kong 20/20: Reflections on a Borrowed Place – of which Wong was one of the authors – to the Foreign Correspondents Club. Joshua Wong says that Asia Society Hong Kong needs to give a “reasonable explanation” for the incident.

“The mission of PEN Hong Kong is to promote literature and defend the freedom of expression. To bar one of the contributors to our anthology, whether it is Joshua Wong or somebody else, from speaking at our launch event would undermine and in fact contravene that mission,” said PEN Hong Kong President Jason Y. Ng.

Back to November 2016, Asia Society Hong Kong also canceled a scheduled screening of Raise The Umbrellas, a documentary on the 2014 Occupy protests with appearance of Joshua Wong. Asia Society Hong Kong has similarly cited the lack of balanced speaker representation at the pre-screening talk as the reason for not screening the film.

US Congressman Chris Smith, co-chairperson of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, expressed that “The Asia Society has some explaining to do after two events that featured Joshua Wong prominently were canceled over the past nine months,” said the New Jersey representative. “I commend PEN Hong Kong for not appeasing the Asia Society’s demands.”....

On July 10, 2017, Forbes magazine ran an article revealing Hong Kong real estate magnate and Asia Society Co-chair Ronnie Chan (a US citizen) to be the political force behind the Joshua Wong incident. It alleged that wealthy Asians have been behind US think tanks and NGOs and effectively turning them into foreign policy tools of the People's Republic of China (Beijing).

-- Asia Society, by Wikipedia

On December 11, 2020, Demaneuf—a stickler for accuracy—reached out to Metzl to alert him to a mistake on his blog. The 2004 SARS lab escape in Beijing, Demaneuf pointed out, had led to 11 infections, not four. Demaneuf was “impressed” by Metzl’s immediate willingness to correct the information. “From that time, we started working together.”

“If the pandemic started as part of a lab leak, it had the potential to do to virology what Three Mile Island and Chernobyl did to nuclear science.”

Metzl, in turn, was in touch with the Paris Group, a collective of more than 30 skeptical scientific experts who met by Zoom once a month for hours-long meetings to hash out emerging clues. Before joining the Paris Group, Dr. Filippa Lentzos, a biosecurity expert at King’s College London, had pushed back online against wild conspiracies. No, COVID-19 was not a bioweapon used by the Chinese to infect American athletes at the Military World Games in Wuhan in October 2019.

The 2019 Military World Games and Sick Athletes

The 7th International Military Sports Council Military World Games (MWGs) opened in Wuhan on October 18, 2019. The games are similar to the Olympic games but consist of military athletes with some added military disciplines. The MWGs in Wuhan drew 9,308 athletes, representing 109 countries, to compete in 329 events across 27 sports. Twenty-five countries sent delegations of more than 100 athletes, including Russia, Brazil, France, Germany, and Poland. [65] ["Military Games to Open Friday in China.” China Daily, 17 Oct. 2019, http://www.china.org.cn/sports/2019- 10/17/content_75311946.htm.]

The PRC government recruited 236,000 volunteers for the games, which required 90 hotels, three railroad stations, and more than 2,000 drivers. [66] [“2019 Military World Games Kicks off in Central China's Wuhan.” CISION, 17 Oct. 2019, http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases ... orldgames- kicks-off-in-central-chinas-wuhan-300940464.html.] An archived version of the competition’s website from October 20, 2019, lists the more than thirty venues that hosted events for the MWGs across Wuhan and the broader Hubei province. [67] [“Competition Venues.” Wuhan 2019 Military World Games, https://web.archive.org/web/20191020154 ... on_venues/.] The live website is no longer accessible – it is unclear why it was removed.

During the games, many of the international athletes became sick with what now appear to be symptoms of COVID-19. In one interview, an athlete from Luxembourg described Wuhan as a “ghost town,”[68] [Houston, Michael. “More athletes claim they contracted COVID-19 at Military World Games in Wuhan.” Inside the Games, 17 May 2020, https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles ... s-covid-19] and recalls having his temperature taken upon arriving at the city’s airport. In an interview with The Financial Post, a Canadian newspaper, one member of the Canadian Armed Forces who participated in the games said (emphasis added):This was a city of 15 million people that was in lockdown. It was strange, but we were told this was to make it easy for the Games’ participants to get around. [I got] very sick 12 days after we arrived, with fever, chills, vomiting, insomnia.… On our flight to come home, 60 Canadian athletes on the flight were put in isolation [at the back of the plane] for the 12-hour flight. We were sick with symptoms ranging from coughs to diarrhea and in between. [69] [Francis, Diane. “Diane Francis: Canadian Forces Have Right to Know If They Got COVID at the 2019 Military World Games in Wuhan.” Financial Post, 25 June 2021, https://financialpost.com/diane-francis ... taryworld- games-in-wuhan.]

The service member also revealed his family members became ill as his symptoms increased, [70] [Ibid.] a development that is consistent with both human-to-human transmission of a viral infection and COVID-19. Similar claims about COVID-19 like symptoms have been made by athletes from Germany, France, Italy, [71] [Houston.] and Sweden. [72] [Liao, George. “Coronavirus May Have Been Spreading since Wuhan Military Games Last October.” Taiwan News, 13 May 2020, http://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3932712.]

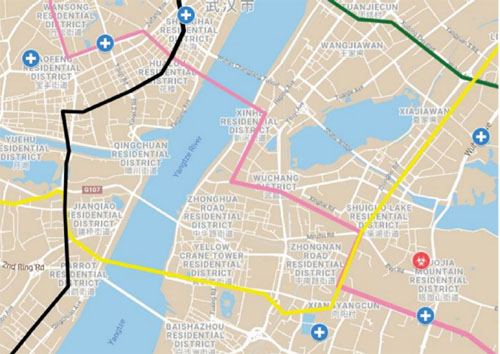

By cross referencing the listed MWG venues with publicly available mapping data, it is possible to visualize the venues (in black) in relation to the WIV Headquarters (in red) and the abovementioned hospitals (in blue). The green figures represent athletes who have publicly expressed their belief they contracted COVID-19 while in Wuhan and are mapped at the venues which hosted the events in which they competed. Some of these athletes resided in the military athletes’ village.

Map 2: WIV Headquarters, Hospitals, MWG Venues, and Sick Athletes

At least four countries who sent delegations to the MWGs have now confirmed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 cases within their borders in November and December 2019, before the news of an outbreak first became public....

As stated above, athletes from France, Italy, and Sweden also complained of illnesses with symptoms similar to COVID-19 while at the MWGs in Wuhan. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in four countries, on two separate continents, suggests a common source. If, as presumed, SARS-CoV-2 first infected humans in Wuhan before spreading to the rest of the world, the 2019 Military World Games in Wuhan appears to be a key vector in the global spread – in other words, potentially one of the first “super spreader” events.

-- The Origins of COVID-19: An Investigation of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, by House Foreign Affairs Committee

But the more she researched, the more concerned she became that not every possibility was being explored. On May 1, 2020, she published a careful assessment in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists describing just how a pathogen could have escaped the Wuhan Institute of Virology. She noted that a September 2019 paper in an academic journal by the director of the WIV’s BSL-4 laboratory, Yuan Zhiming, had outlined safety deficiencies in China’s labs. “Maintenance cost is generally neglected,” he had written. “Some BSL-3 laboratories run on extremely minimal operational costs or in some cases none at all.”

Alina Chan, a young molecular biologist and postdoctoral fellow at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University, found that early sequences of the virus showed very little evidence of mutation. Had the virus jumped from animals to humans, one would expect to see numerous adaptations, as was true in the 2002 SARS outbreak. To Chan, it appeared that SARS-CoV-2 was already “pre-adapted to human transmission,” she wrote in a preprint paper in May 2020.

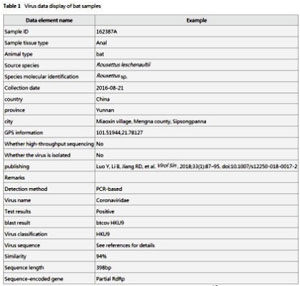

But perhaps the most startling find was made by an anonymous DRASTIC researcher, known on Twitter as @TheSeeker268. The Seeker, as it turns out, is a young former science teacher from Eastern India. He had begun plugging keywords into the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, a website that houses papers from 2,000 Chinese journals, and running the results through Google Translate.

One day last May, he fished up a thesis from 2013 written by a master’s student in Kunming, China. The thesis opened an extraordinary window into a bat-filled mine shaft in Yunnan province and raised sharp questions about what Shi Zhengli had failed to mention in the course of making her denials.