by Stephen Greenblatt

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

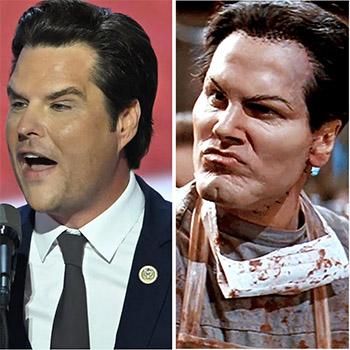

Trump: Long Live the King!

IN DEPICTING THE aspiring tyrant's strategy, Shakespeare carefully noted among the landed classes of his time the strong current of contempt for the masses and for democracy as a viable political possibility. Populism may look like an embrace of the have-nots, but in reality it is a form of cynical exploitation. The unscrupulous leader has no actual interest in bettering the lot of the poor. Surrounded from birth with great wealth, his tastes run to extravagant luxuries, and he finds nothing remotely appealing in the lives of underclasses. In fact, he despises them, hates the smell of their breath, fears that carry diseases, and regards them as fickle, stupid, worthless and expendable. But he sees that they can be made to further his ambitions.

It is not the well-meaning king, or the principled civil ' servant Duke Humphrey, who understands what is down there at thevery bottom of the realm. It is York's genius, if that is the right word for something so base, to grasp the use he can make of the resentment that seethes among the poorest of the poor. "I will stir up in England some black storm," he broods to himself, a storm that will not cease to rage until the crown he plans to seize -- "the golden circuit on my head" -- shines like the sun and calms the fury. And he has, he reveals, found the perfect person to be his agent: "I have seduced a headstrong Kentishman,/John Cade" (2 Henry VI 3.1.349-57).

John (or Jack) Cade was an actual person- -- a lower-class rebel about whom few personal details are known -- who led a bloody popular revolt that flared up against the English government in I 450 and was quickly and violently suppressed: To fashion his character, Shakespeare cobbled together materials he gathered from the historical chronicles (including the charge that Cade was secretly funded by York), combined them with the traces of other peasant uprisings, and added details drawn from his own vivid imagination.

The grand Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, does not care in the slightest about the ultimate fate of the base man he has seduced into furthering his designs, and he cares still less about the ragged mob he intended to stir up into rebellion. But he has observed Cade carefully and seen qualities that may make him useful, including an uncanny indifference to pain and, therefore, an ability to keep hidden their secret bond:

Say he be taken, racked, and tortured,

I know no pain they can inflict upon him

Will make him say I moved him to those arms.

(3.1.376-78)

Secrecy is important: it would not do for the powerful aristocrat to be revealed as the instigator of a vicious popular uprising.

The uprising turns out to be an even greater storm than York could have wished. The mob, gathering just outside London in Blackheath, is rallied by Cade, who proves himself to be an effective demagogue, the master of voodoo economics:

There shall be in England seven halfpenny loaves sold for a penny, the three-hooped pot shall have ten hoops, and I will make it felony to drink small beer. All the realm shall be in common ..... [T]here shall be no money; all shall eat and drink on my score. (4.2.61-68)

When the crowd roars its approval, Cade sounds exactly like a modern stump speaker: "I thank you, good people" (4.2.167).

The absurdity of these campaign promises is not an impediment to their effectiveness. On the contrary: Cade keeps producing demonstrable falsehoods about his origins and making wild claims about the great things he will do, and the crowds eagerly swallow them. To be sure, his neighbors know that Cade is a congenital liar:

CADE: My mother a Plantagenet --

BUTCHER: [Aside] I knew her well; she was a midwife.

CADE: My wife descended of the Lacys --

BUTCHER: [Aside] She was indeed a peddler's daughter and sold laces. (4.2.39-43)

Cade's absurd assertions of aristocratic lineage should make him seem merely a buffoon. Far from a wealthy, high-born magnate, he is little more than a vagabond: "I have seen him whipped three market days together" (4.2.53-54), whispers one of his supporters. But, strangely enough, this knowledge does not diminish the mob's faith.

Cade himself, for all we know, may think that what he is so obviously making up as he goes along will actually come to pass. Drawing on an indifference to the truth, shamelessness, and hyperinflated self-confidence, the loudmouthed demagogue is entering a fantasyland -- "When I am king, as king I will be" -- and he invites his listeners to enter the same magical space with him. In that space; two and two do not have to equal four, and. the most recent assertion need . not remember the contradictory assertion that was· made a few seconds earlier.

In ordinary times, when a public figure is caught in a lie or simply reveals blatant ignorance of the truth, his standing is diminished. But these are not ordinary times. If a dispassionate bystander were to point out all of Cade's grotesque distortions, mistakes, and downright lies, the crowd's anger would light on the skeptic and not on Cade. Famously, it is at the end of one of Cade's speeches that someone in the crowd shouts, "The first thing we do, let's kill all the lawyers" (4.2.71).

Shakespeare knew that the line would get laughs, as it has done for the last four centuries. It releases the current of aggression that swirls around the whole enterprise of the law -- directed not merely at venal attorneys but at all the agents of the vast social apparatus that compels the honoring of contracts, the payment of debts, the fulfillment of obligations. We blithely imagine that the crowd wants such responsible qualities in its leaders, but the scene suggests otherwise. What it wants instead is permission to ignore commitments; to violate promises, and to break the rules.

Cade begins by talking vaguely about "reformation," but his actual appeal is wholesale destruction. He urges the mob to pull down London's law schools, the Inns of Court, but that is only the beginning. "I have a suit unto your lordship," entreats one of his chief followers, "that the laws of England may come out of your mouth" (4.7.3-7). "I have thought upon it," Cade replies, "it shall be so. Away! Burn all the records of the realm; my mouth shall be the Parliament of England" (4.7-.11-13).

That in this destruction the common people would lose even the very limited power they possess -- the power expressed when they voted in parliamentary elections -- does not matter. For Cade's ardent supporters, the time-honored institutional system of representation is worthless. It has, they feel, never represented them. Their inchoate wish is to tear up all the agreements, cancel all the debts, and wreck all the existing institutions. Better to have the law come from the mouth of the dictator, who may claim to be a Plantagenet but whom they recognize as one of their own. The masses are perfectly aware that he is a liar, but -- venal, cruel, and self-serving though he is -- he succeeds in articulating their dream: "Henceforward all things shall be in common" (4.7.16).

Cade's rant stands in for any transparency about his own past. and any serious commitment to make good on this or that particular promise. Far from demanding that he keep his word, his followers are gratified when he rails against all contracts: "Is not this a lamentable thing, that the skin of an innocent lamb should be made parchment; that parchment, being scribbled o'er, should undo a man?, (4.2.72-75). The remark about the "scribbled-over" parchment is at once ridiculous -- how else should legal documents look? -- and canny. The poor whose passions Cade is arousing feel excluded, despised, and vaguely ashamed. They have been left out of an economy that increasingly demands possession of a once-esoteric technology: literacy. They do not imagine that they can master this new skill, nor does their leader propose that they undertake any education. It would hardly suit his purposes if they did so. What he does instead is manipulate their resentment of the educated.

The mob quickly apprehends a clerk and levels an accusation against him: "he can write and read." Indeed, his accusers report, "We took him setting of boys' copies" (4.2.81) -- that is, preparing writing exercises for schoolboys. Cade undertakes to conduct the interrogation: "Dost thou use to write thy name,'' he asks. "Or hast thou a mark to thyself, like a honest plain-dealing man?" (4.2.92-93). If the clerk knew what was good for him, he would insist that he was illiterate and signed his name only with a mark. Instead he proudly proclaims his accomplishment: "Sir, I thank God I have been so well brought up that I can write my name." "He hath confessed!" the mob shouts. ''Away with him! He's a villain and a traitor." "Away with him, I say!" orders Cade, echoing the crowd's demand. "Hang him with his pen and ink-horn about his neck" (4.2.94-99).

Jack Cade longs for the time when, as he puts it, boys played games of toss "for French crowns," a time before the country was "maimed and fain to go with a staff" (4.2.145-50). Until weaklings led it astray, he suggests, England compelled its enemies to tremble before its power, and that glorious swaggering must now be recovered. He promises to make England great again. How will he do that? He shows the crowd at once: he attacks education. The educated elite has betrayed the people. They are traitors who will all be brought to justice, and this justice will be meted out not by judges and lawyers but in a call-and-response between the leader and his mob. The English treasurer Lord Saye "can speak French" -- "and therefore he is a traitor" (4.2.153). It makes perfect sense: "The Frenchmen are our enemies .... I ask but this: can he that speaks with the tongue of an enemy be a good counselor, or no?" The crowd roars the answer: "No, no -- and therefore we'll have his head!" (4.2.155-58).

When the mob, having broken through London's defenses, streams into the city and captures this very Lord Saye, Cade experiences the full flush of triumph. He has in his hands the realm's highest fiscal officer, the emblem of the swamp that he has pledged to drain. (The demagogue's actual metaphor for what he intends to do is slightly homelier:. "Be it known," he declares, "that I am the besom" -- the broom -- "that must sweep the court clean of such filth as thou art" [4.7.27-28].) With his excited followers hanging on every word, he enumerates the charges against his prisoner. He accuses Saye of having done something even worse than giving Normandy to the French:

Thou hast most traitorously corrupted the youth of the realm in erecting a grammar school; and whereas, before, our forefathers had no other books but the score and the tally, thou hast caused printing to be used, and, contrary to the King, his crown, and dignity, thou hast built a paper mill. (4.7.28-33)

Helping foster an educated citizenry -- people who read books -- is Saye's most egregious crime. And Cade has corroborating evidence: "It will be proved to thy face that thou hast men about thee that usually talk of a noun and a verb and such abominable words no Christian ear can endure to hear" (4.7.33-36).

We are meant to find this ridiculous, of course; the scene is quite rightly played for laughs. But Shakespeare grasped something critically important: although the absurdity of the demagogue's rhetoric was blatantly obvious, the laughter it elicited did not for a minute diminish its menace. Cade and his followers will not slink away because the traditional political elite and the entirety of the educated populace regard him as a jackass.

That Cade himself understands the base of his power is suggested by the lines that immediately follow his drivel about nouns and verbs. "Thou hast appointed justices of the peace," he charges Lord Saye,

to call poor men before them about matters they were not able to answer. Moreover, thou hast put them in prison and, because they could not read, thou hast hanged them, when indeed only for that cause they have been most worthy to live. (4.7.36-41)

In some sense, this rant is an extension of the rubbish Cade has been spouting: it is ridiculous for him to suggest that criminals deserve to be pardoned simply because they are illiterate. But the joke begins to curdle. The play has already amply shown that the rich and well-born can get away with murder. Moreover, Shakespeare's audience was well aware that the courts in their own time allowed something called "benefit of clergy," a legal device whereby those condemned to be executed for murder or theft could, if they demonstrated that they were literate, be remanded to jurisdictions which had no death penalty. Cade's accusation that those who could not read were hanged is perfectly accurate -- and it gets at a whole legal system heavily weighted to favor the educated elite.

Small wonder then that there is a fathomless pool of lower-class resentment upon which Cade can draw, and small wonder, too, that the ridicule and contempt heaped upon him and his followers only intensifies this resentment. "Rebellious hinds, the filth and scum of Kent, / Marked for the gallows," the royal officer Sir Humphrey Stafford rails at the mob, "lay your weapons down! / Home to your cottages" (4.2.111-13). Calling them "filth and scum" simply helps highlight the ceremonious show of respect their leader offers them: "It is to you, good people, that I speak," Cade tells them, "Over whom, in time to come, I hope to reign, / For I am rightful heir unto the crown" (4.2.118-20). Once again he advances his grotesque lie, and once again there is an official attempt to expose it: "Villain, thy father was a plasterer," Stafford fumes. To this Cade replies, "And Adam was a gardener" (4.2.121-23).

This reply is something more than a simple non sequitur. Cade's words allude to the slogan of the Peasants' Revolt in the late fourteenth century: "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?" The peasants' leader, the revolutionary priest John Ball, spelled out the meaning of his incendiary little rhyme: "From the beginning all men were created equal by nature." Before it was over, rebels had torched court records, opened jails, and killed officials of the crown.

Shakespeare carries over into his depiction of Cade's uprising the fear and loathing aroused among the propertied classes by lower-class insurgency. The peasant rebels are fueled by something like the murderous vision of Cambodia's Pol Pot: their goal is to destroy not merely the high-ranking nobles but the entire educated population of the country. "All scholars, lawyers, courtiers, gentlemen," one appalled observer reports. "They call false caterpillars and intend their death" (4.4.35-'36). The common people have been exploited and enslaved; this is the moment for them to seize liberty. "We will not leave one lord, one gentleman," Cade chillingly promises, exhorting his followers to "Spare none but such as go in clouted shoon" (4.2.169-70) -- that is, in the hobnailed boots of peasants. The rural poor have not joined the rebelling urban masses, but the peasants, as Cade puts it, are "such / As would, but that they dare not, take our parts" (4.2.172). They are fellow travelers in the war of the ignorant against the literate and would, if they had the courage, applaud the grisly end he orders for the likes of the well-spoken Lord Saye: "Go, take him away, I say, and strike off his head presently, and then break into his son-in-law's house, Sir James Cromer, and strike off his head, and bring them both upon two poles hither" (4.7.99-101).

When his command is carried out, and the heads are duly brought to him, Cade arranges a piece of sadistic political theater. "Let them kiss one another," he orders, "for they loved well when they were alive." Then he adds, with the cruel sarcasm that perfectly typifies this kind of demagogu, "Now part them again, lest they consult about the giving up of some more towns in France" (4.7.119-22).

Cade aspires to being a tyrant, and a rich one at that: "The proudest peer in the realm shall not wear a head on his shoulders unless he pay me tribute" (4.7.109-10). He imagines for himself, as well, the right to sleep, with all the women he can put his hands on. For a time, he manages to whip his followers into a frenzy of destructiveness: "Up Fish Street! Down Saint Magnus' Corner! Kill and knock down! Throw them into Thames!" (4.8.1-2). But he has no organizational skills or party on which to draw, and we know (though his followers do not) that he is merely the tool of the sinister York.

When the moment is ripe, by borrowing from Cade's own book and appealing to nativist sentiments and dreams of plunder, the royal authorities lure the mob away from their rebellion and in a different direction -- "To France, to France, and get what you have lost!" Isolated and embittered, Cade flees for his life, cursing those who had followed him:

I thought ye would never have given out these arms till you had recovered your ancient freedom. But you are all recreants and dastards and delight to live in slavery to the nobility. Let them break your backs with burdens, take your houses over your heads, ravish your wives and daughters before your faces. (4.8.23-29)

When we next see Cade, he is a starving fugitive, breaking into a garden "to see if I can eat graas, or pick a salad" (4.10.6-7). The garden's owner easily dispatches the emaciated rebel with his sword and drags his corpse "Unto a dunghill which shall be thy grave'' (4.10.76).

King Henry breathes a sigh of relief, but the news of Cade's downfall is accompanied at almost the same moment by word that York, with an Irish army, is advancing toward the royal encampment; York is clever enough to keep his intentions hidden until he has strength enough to act, but he makes clear in his soliloquies that he will settle for nothing less than the crown. What follows is a complex tangle of events, mingling wars in France with domestic conspiracy, treachery, and violence. The outcome is full-scale war between the two parties, the red roses and the white, Lancastrians and Yorkists.

The horrors of this war epitomize the breakdown of basic values -- respect for order, civility, and human decency -- which paves the way for the tyrant's rise. The seeds of the breakdown had already been glimpsed in the argument between York and Somerset, where a disagreement over an obscure point of law had quickly escalated into a barrage of insults. The anger was intensified by the rise of party politics and then, through York's subterfuge, had led to the murder of Duke Humphrey and Jack Cade's rebellion. But civil war lifts the veil of subterfuge: the principal political figures no longer hide their highest ambitions or leave the enactment of their sadistic impulses to their subordinates. The byzantine complexity of the plot from this point forward has made the final play of Shakespeare's trilogy notoriously difficult to stage, but several things are particularly notable.

First, rising chaos makes the outcome of the struggle for power completely unpredictable. When he was operating in the half-shadows and effecting his wishes through substitutes like Cade, York had seemed almost invulnerable. But once he is in the open -- at one point he actually seats himself on the throne, though he is quickly forced to step down -- he and his family become direct targets of the opposing faction. His enemies capture and kill his twelve-year-old son. When, shortly afterward, they capture York himself, they mockingly offer him a handkerchief soaked in his son's blood. Then they taunt him and adorn him with a paper crown before stabbing him to death. Such is the vicious cruelty that he himself has helped to release and legitimate, and such, too, is the end of the would-be tyrant.

Second, the dream of absolute rule is not the goal of a single person alone; in the political conception of the age, it is a dynastic ambition, a family affair. In an age in which power routinely passed from father to the eldest son (or, in the absence of sons, to the eldest daughter), it made perfect sense for tyrants to model themselves after the monarchs they sought to displace and to attempt to secure power for their heirs. Even in democratic systems where succession is determined by vote, we have by no means left dynastic ambition behind; it seems, if anything, to be intensifying in contemporary politics. Besides, who can the perennially insecure tyrant trust more than the members of his own family?

But family interest is only one element in the continuing turmoil Shakespeare depicts. The turmoil is also a consequence of party politics, symbolized here by the plucking of the white and red roses. York's death is significant blow to his party, but it by no means puts an end to the struggle to destroy the legitimate monarch. The Yorkists find a new candidate, York's son Edward, and advance his claim in any way they can.

Third, the political party determined to seize power at any cost makes secret contact with the country's traditional enemy. England's enmity with the nation across the Channel -- constantly fanned by all the overheated patriotic talk of recovering its territories there, and fueled by all the treasure and blood spilled in the attempt to do so -- suddenly vanishes. The Yorkists -- who, in the person of Cade, had pretended to consider it an act of treason even to speak French -- enter into a set of secret negotiations with France. Nominally, the negotiations aim to end hostilities between the two countries by arranging a dynastic marriage, but they actually spring, as Queen Margaret cynically observes, "from deceit, bred by necessity" (3 Henry VI 3.3.68). To bring Edward Plantagenet to the throne, the Yorkists seek to enhance their candidate's power. He still lacks the strength to topple Henry, and his party will obtain that strength wherever they can find it, even if it means betraying their country. It does not matter that the Yorkists have constantly lamented the loss of so much territory to their hated rivals, the French, and have vociferously blamed Henry for the loss. Now suddenly the Yorkists make a show of "kindness and unfeigned love" (3.3.51) to their enemy. Ardent patriots like Talbot are hopelessly naive to believe that loyalty to the nation trumps personal interest. A cynical insider like Queen Margaret knows better: "How can tyrants safely govern home," she asks, "Unless abroad they purchase great alliance?" (3.3.69-70).

Fourth, the legitimate, moderate leader cannot count on popular gratitude or support. In the chaotic free-for-all into which the realm has fallen, this apparent betrayal of principle does hot produce any great outrage. What might at another time have provoked charges of treason is simply accepted as the way things are. And if there are no longer the expected punishments for treachery, so, too, there are no longer the anticipated rewards for virtue. Perhaps such anticipation was always a delusion: a decent ruler should never count on the gratitude of the people. That had already been demonstrated in the Cade rebellion, but it is brought home again, still more fatally, at the climax of the civil war. Just before his downfall, Henry expresses confidence that his subjects will support him because he has always been a reasonably just, caring, and moderate king. The claim is true enough; the mistake, a fatal one, is to think that this will earn him secure popular support. "I have not stopped mine ears to their demands," Henry reassures himself,

Nor posted off their suits with slow delays.

My pity hath been balm to heal their wounds;

My mildness hath allayed their swelling griefs;

My mercy dried their water-flowing tears.

I have not been desirous of their wealth

Nor much oppressed them with great subsidies,

Nor forward of revenge, though they much erred.

Then why should they love Edward more than me? (4.9.7-15)

But when the moment of truth comes, in the battle that decides whether the Yorkists will finally succeed in seizing power; there is no rush of popular support for the virtuous Henry. First his son and heir is captured and stabbed to death by the sons of York, and then it is his own turn to die at the hands of Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the most ruthless of these sons. The Yorkist leader, Edward Plantagenet, ascends the throne.

And fifth, the apparent restoration of order, in the wake of national turmoil, may be an illusion. Eager to "spend the time / With stately triumphs, mirthful comic shows" (5.7.42-43), Edward is a more moderate figure than York, his father, far less consumed with fantasies of absolute power. To return the country to a semblance of normal, legitimate rule, he hopes to bring about a collective forgetting of the nightmare from which everyone has barely awakened. In this spirit of amnesia, he characterizes the bloodshed that his party has caused a "sour annoy." And he cheerfully declares that the threats have all vanished: "Thus have we swept suspicion from our seat / And made our footstool of security" (5.7.I1-14).

Everything in the realm, in the new king's final words, seems happily settled: "For here I hope begins our lasting joy" (5.7.46). Yet at the close of Shakespeare's Wars of the Roses trilogy, the audience knows that the joy will be anything but lasting. Edward largely owed his party's victory and, hence, his kingship to his stalwart brothers, George, Duke of Clarence, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester. George, to be sure, wavered at one point in the civil war, siding briefly with the Lancastrians, but he came back to fight for the Yorkist cause. Richard never wavered, and it was he who murdered Henry VI. But with the king bleeding to death at his feet, Richard had quietly made it clear that his only allegiance was to himself. "I have no brother," he declared. "I am myself alone" (5.6.80-83). A new tyrant is waiting in the wings.

***************************

Tyrant by Stephen Greenblatt review – Shakespeare, power and sadistic impulses: The literary scholar leaves parallels with today inexplicit, but has written an engaging study of some of the most eloquent despots on stage

by John Mullan

The Guardian

Fri 6 Jul 2018 03.59 EDT

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/ ... att-review

Near the end of this book, Stephen Greenblatt observes that Shakespeare was unusually good at staying out of trouble. His friend and rival Ben Jonson was imprisoned for the allegedly seditious play The Isle of Dogs. Their contemporary, Thomas Kyd, fled from an arrest warrant for sedition and was interrogated under torture. Christopher Marlowe was stabbed to death by a government agent, while awaiting an investigation of his unconventional religious beliefs. The career of playwright was not a safe one in Elizabethan or Jacobean England. Greenblatt’s opening chapter lays out the evidence for the dangers of staging drama in Shakespeare’s day, culminating in the elderly Elizabeth I reportedly likening herself to Shakespeare’s Richard II, a monarch defeated and finally murdered by rebels.

Yet Richard II was never banned. Shakespeare prospered while creating his anatomies of power and its abuse. No reader of this single-minded book could be in any doubt of Shakespeare’s fascination with the ways in which a tyrant exercised power. Some of his greatest characters are tyrants, displayed for spectators who knew that, outside the theatre, political dissent or religious heterodoxy could be death. Some of the most memorably caustic lines about the arbitrariness of authority – “a dog’s obeyed in office” – were spoken on Shakespeare’s stage to an audience that included government agents. Yet, as Greenblatt puts it with winning anachronism, “the police were never called”. If the maddened Lear said it, it was allowable. Sentiments that would have been dangerous to voice in the tavern could be broadcast at the Globe.

Greenblatt is returning here to some of the questions that occupied him in the early criticism that made his name, and that established him as the leading light of new historicism. That critical movement specialised in audacious sallies of interpretation; in contrast, this book sticks to dutiful exegesis of Shakespeare’s dialogues. New historicism allowed critics to flourish their ingenuity by finding repressed meanings that their chosen authors had not themselves acknowledged. Now Greenblatt seems almost to believe in the playwright’s intentions.

Anyone who has struggled with Shakespeare’s earliest history plays, his Henry VI trilogy, will be pleased to find here a condensed account of the conspiracy and treachery they dramatise, including the terrifying rise and inevitable fall of the rebel Jack Cade. It is a story of the “sadistic impulses” shared by those who love power. These three plays were the prelude to Richard III, whose warped protagonist appals and captivates Greenblatt. Richard’s skill is “the ability to force his way into the minds of those around him”. He is definitive on Richard’s psychopathology. “Sexual conquest excites him, but only for the endlessly reiterated proof that he can have anything he likes.”

Tyranny is a madness that becomes eloquent in Shakespeare. Not for him the banality of the despot. Macbeth may be a “butcher”, but no one speaks better. Leontes in A Winter’s Tale turns language itself into a fevered, flickering register of paranoia. In every way, these characters are compelling. As Greenblatt elegantly shows, Shakespeare dramatises the very exercise of power – the ways in which subjects and collaborators are seduced or numbed into complicity. Those few who resist intrigue him. The book’s hero is the Duke of Cornwall’s unnamed servant in King Lear who, with his master urged on by his wife Regan to pluck out Gloucester’s eyes, calls on him to stop. The man has served Cornwall “since I was a child”, but now shows his “better service” by trying to stand between the torturer and his victim. “A peasant stand up thus?” is Regan’s contemptuous question, as she stabs him to death.

Greenblatt is not unerring. He says that in Macbeth we witness “the birth of a tyrant” in the famous dialogue where Lady Macbeth goads her hesitating husband into murder. Yet the play is careful to let us know that the scheme to murder Duncan has been hatched some time before the play begins. The witches are not putting something into his head but reminding him of his own dark plans. He is already the would-be tyrant. There is also some uncertainty about what a tyrant is. We get a sharply observed chapter on Coriolanus, but its protagonist is revealed to be anything but a tyrant. He is disabled from wielding power by his distaste for the business of winning over the populace. As Greenblatt himself points out, Coriolanus’s political opponents manipulate him precisely by depicting him to the people as a would-be tyrant. A better candidate for inclusion would surely have been Hamlet’s uncle Claudius, a ruler who can manage sweet reason in his speeches alongside utter ruthlessness in his orders. And what about the Puritan tyrant Angelo in Measure for Measure, soberly making others pay for what are in fact his own sins?

The book may have begun as a newspaper article, drawing lessons from Shakespeare on the eve of the 2016 presidential election, but mostly the reader is left to draw his or her lessons for the present. There are some calculatedly anachronistic analogies: Mary Queen of Scots’ beheading is likened to the killing of Osama bin Laden. Greenblatt admires Shakespeare as “the master of the oblique angle” on power – and wants to find that angle for himself.

Tyrant: Shakespeare on Power is published by Bodley Head. To order a copy for £14.44 (RRP £16.99) go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.