by Jessica Corbett

Common Dreams

Mar 06, 2025

A federal judge on Thursday reinstated Gwynne Wilcox, a Democratic member of the National Labor Relations Board, and suggested that U.S. President Donald Trump's attempt to fire her was an example of the Republican testing how much he can exceed his constitutional powers.

Wilcox filed a federal lawsuit in February, after Trump ousted her and NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo. On Thursday, U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell—who was appointed by former President Barack Obama to serve in the District of Columbia—declared Wilcox's dismissal "unlawful and void."

"The Constitution and case law are clear in allowing Congress to limit the president's removal power and in allowing the courts to enjoin the executive branch from unlawful action," Howell wrote in a 36-page opinion. She also sounded the alarm about arguments made by lawyers for the defendants, Trump and Marvin Kaplan, chair of the NLRB.

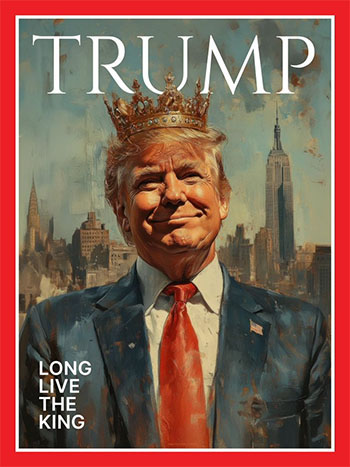

"A president who touts an image of himself as a 'king' or a 'dictator,' perhaps as his vision of effective leadership, fundamentally misapprehends the role under Article II of the U.S. Constitution."

12:31 PM · Feb 19, 2025

"Defendants' hyperbolic characterization that legislative and judicial checks on executive authority, as invoked by plaintiff, present 'extraordinary intrusion[s] on the executive branch,' ...is both incorrect and troubling," the judge wrote. "Under our constitutional system, such checks, by design, guard against executive overreach and the risk such overreach would pose of autocracy."

She stressed that "an American president is not a king—not even an 'elected' one—and his power to remove federal officers and honest civil servants like plaintiff is not absolute, but may be constrained in appropriate circumstances, as are present here."

"A president who touts an image of himself as a 'king' or a 'dictator,' perhaps as his vision of effective leadership, fundamentally misapprehends the role under Article II of the U.S. Constitution," Howell asserted. "In our constitutional order, the president is tasked to be a conscientious custodian of the law, albeit an energetic one, to take care of effectuating his enumerated duties, including the laws enacted by the Congress and as interpreted by the judiciary."

The judge cited a widely criticized February 19 social media post from the White House, which features an image of Trump in a crown, with text that states, "Long live the king."

"The president seems intent on pushing the bounds of his office and exercising his power in a manner violative of clear statutory law to test how much the courts will accept the notion of a presidency that is supreme," Howell warned. "The courts are now again forced to determine how much encroachment on the legislature our Constitution can bear and face a slippery slope toward endorsing a presidency that is untouchable by the law."

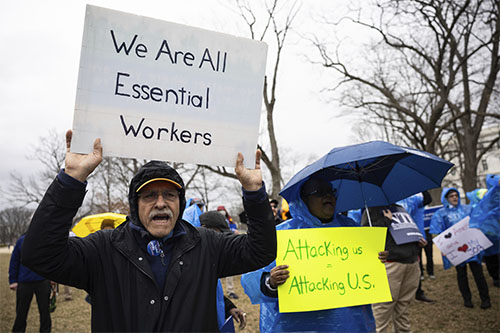

The president's attempt to fire Wilcox halted federal labor law enforcement in the United States. AFL-CIO president Liz Shuler celebrated Howell's ruling in a Thursday statement, saying that "more than a month after Trump effectively shut down the NLRB by illegally firing Gwynne Wilcox, denying it the quorum it needs to hold union-busters accountable, the court ordered Wilcox immediately returned to her seat, allowing the NLRB to get back to its essential work."

"The court also sent an important message that a president cannot undermine an independent agency by simply removing a member of the board because he disagrees with her decisions," she said. "Working people around the country count on equal justice and fair decision-making from an independent NLRB—and today, because of Wilcox's commitment to the mission of the NLRB and her refusal to stand by as Trump illegally removed her from the board, the NLRB can get back to work."

Wilcox isn't the only federal worker who has challenged the president's power to fire her. As Politico detailed:

On Thursday, a federal workplace watchdog fired by Trump—Special Counsel Hampton Dellinger—dropped his legal bid to reclaim his post after a federal appeals court permitted his termination. Cathy Harris, a member of the Merit Systems Protection Board, which oversees the grievance process for many federal employees, is also resisting Trump’s effort to remove her and was reinstated last month by a federal judge.

The Supreme Court likely will soon weigh in on Congress' ability to insulate executive branch officials from being fired by the president without cause. With Dellinger's decision to drop his legal fight, Harris' case appears likeliest to reach the high court in the near-term. It’s possible Wilcox's case will get folded into that ongoing fight.

The nation's highest court has a right-wing supermajority that includes three Trump appointees, though they have at times ruled against the president—including on Wednesday, when five justices refused to overturn a lower court order about foreign aid.

********************

Part 1 of 2

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

GWYNNE A. WILCOX,

Plaintiff,

v.

DONALD J. TRUMP, in his official capacity as President of the United States

and

MARVIN E. KAPLAN, in his official capacity as Chairman of the National Labor Relations Board,

Defendants.

Civil Action No. 25-334 (BAH)

Judge Beryl A. Howell

MEMORANDUM OPINION

Scholars have long debated the degree to which the Framers intended to consolidate executive power in the President. The “unitary executive theory”—the theory, in its purest form, that, under our tri-partite constitutional framework, executive power lodges in a single individual, the President, who may thus exercise complete control over all executive branch subordinates without interference by Congress—has been lauded by some as the hallmark of an energetic, politically accountable government, while rebuked by others as “anti-American,” a “myth,” and “invented history.”1 Both sides of the debate raise valid concerns, but this is no mere academic exercise.2 The outcome of this debate has profound consequences for how we Americans are governed. On the one hand, democratic principles militate against a “headless fourth branch”3 made up of politically unaccountable, independent government entities that might become agents of corrupt factions or private interest groups instead of the voting public. Additionally, at least theoretically, empowering a President with absolute control over how the Executive branch operates, including the power to “clean house” of federal employees, would promote efficient [???]implementation of presidential policies and campaign promises that are responsive to the national electorate. On the other hand, the advantages of impartial, expert-driven decision-making and congressional checks on executive authority favor some agency independence from political changes in presidential administrations, with the concomitant benefits of stability, reliability, and moderation in government actions. No matter where these pros and cons may lead, the crucial question here is, what does the U.S. Constitution allow?

To start, the Framers made clear that no one in our system of government was meant to be king—the President included—and not just in name only. See U.S. CONST. art. I, § 9, cl. 8 (“No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States.”). Indeed, the very structure of the Constitution was designed to ensure no one branch of government had absolute power, despite the perceived inefficiencies, inevitable delays, and seemingly anti-democratic consequences that may flow from the checks and balances foundational to our constitutional system of governance.

The Constitution provides guideposts to govern inter-branch relations but does not fully delineate the contours of the executive power or the degree to which the other two branches may place checks on the President’s execution of the laws. As pertinent here, the Constitution does not, even once, mention “removal” of executive branch officers. The only process to end federal service provided in the Constitution is impeachment, applicable to limited offices (like judges and the President) after a burdensome political process. See, e.g., id. art. II, § 4 (impeachment of President); id. art. III, § 1 (impeachment of federal judges). This constitutional silence on removal perplexed the First Congress, bedeviled a President shortly thereafter and a second President after the Civil War during Reconstruction (leading to condemnation of the former and impeachment proceedings against the latter), and has beset jurists and scholars in our modern era. See infra Part III.A.3.b.4

Yet, in assessing separation of powers, the Constitution itself is not the only available guide. Historical practice and a body of case law are, respectively, instructive and binding. See infra Part III.A.1; e.g., Zivotofsky ex rel. Zivotofsky v. Kerry, 576 U.S. 1, 23 (2015) (“In separation of powers cases this Court has often ‘put significant weight upon historical practice.’” (quoting NLRB v. Noel Canning, 573 U.S. 513, 524 (2014))). Both make clear that textual silence regarding removal does not confer absolute authority on a President to willy-nilly override a congressional judgment that expertise and insulation from direct presidential control take priority when a federal officer is tasked with carrying out certain adjudicative or administrative functions. As Justice Louis Brandeis eloquently opined, “[c]hecks and balances were established in order that this should be ‘a government of laws and not of men,’” observing further that the separation of powers was not adopted “to promote efficiency but to preclude the exercise of arbitrary power. The purpose was, not to avoid friction, but, by means of the inevitable friction incident to the distribution of the governmental powers among three departments, to save the people from autocracy.” Myers v. United States, 272 U.S. 52, 292-93 (1926) (Brandeis, J., dissenting).

A President who touts an image of himself as a “king” or a “dictator,”5 perhaps as his vision of effective leadership, fundamentally misapprehends the role under Article II of the U.S. Constitution. In our constitutional order, the President is tasked to be a conscientious custodian of the law, albeit an energetic one, to take care of effectuating his enumerated duties, including the laws enacted by the Congress and as interpreted by the Judiciary. U.S. CONST. art. II, § 3 (“[H]e shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed . . . .”). At issue in this case, is the President’s insistence that he has authority to fire whomever he wants within the Executive branch, overriding any congressionally mandated law in his way. See Letter from Sarah Harris, Acting Solicitor General, to Sen. Richard Durbin on Restrictions on the Removal of Certain Principal Officers of the United States (“Letter from Acting SG”) (Feb. 12, 2025), https://perma.cc/D67G-FKK4 (describing the Trump administration’s view of the removal power). Luckily, the Framers, anticipating such a power grab, vested in Article III, not Article II, the power to interpret the law, including resolving conflicts about congressional checks on presidential authority. The President’s interpretation of the scope of his constitutional power—or, more aptly, his aspiration—is flat wrong.

The President does not have the authority to terminate members of the National Labor Relations Board at will, and his attempt to fire plaintiff from her position on the Board was a blatant violation of the law. Defendants concede that removal of plaintiff as a Board Member violates the terms of the applicable statute, see Motions H’rg (Mar. 5, 2025), Rough Tr. at 51:12-13, and because this statute is a valid exercise of congressional power, the President’s excuse for his illegal act cannot be sustained.

I. BACKGROUND

The statutory and procedural background relevant to resolving this dispute is summarized below.

A. Statutory Background

The National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”) was established ninety years ago by Congress in the National Labor Relations Act (“NLRA”) in response to a long and violent struggle for workers’ rights. See generally, J. Warren Madden, Origin and Early Years of the National Labor Relations Act, 18 HASTINGS L.J. 571 (1967); Arnold Ordman, Fifty Years of the NLRA: An Overview, 88 W. VA. L. REV. 15, 15-16 (1985). Congress sought to protect industrial peace and stability in labor relations and thus created a board to resolve efficiently labor disputes and protect the rights of employees to “self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations [and] to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing.” 29 U.S.C. §157; see also id. § 151; Crey v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp., 375 U.S. 261, 271 (1964) (describing these goals); Colgate-Palmolive-Peet Co. v. NLRB, 338 U.S. 355, 362 (1949) (same).

The NLRB is a “bifurcated agency” consisting, on one side, of a five-member, quasi-judicial “Board” that adjudicates appeals of labor disputes from administrative law judges (“ALJs”), and on the other, of a General Counsel (“GC”) and several Regional Directors who prosecute unfair labor practices and enforce labor law and policy. See NLRB, Who We Are, https://perma.cc/9RLA-FSYL; 29 U.S.C. §§ 153(a), (d), 160; Starbucks v. McKinney, 602 U.S. 339, 357 (2024) (Jackson, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). The two sides operate independently, with the GC independent of the Board’s control. NLRB v. United Food & Com. Workers Union, Local 23, AFL-CIO, 484 U.S. 112, 117-18 (1987) (describing how the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947 amended the NLRA to separate the prosecutorial and adjudicatory functions between the Board and General Counsel).

The NLRB generally addresses labor disputes as follows: Upon the filing of a “charge” by an employer, employee, or labor union, a team working under the Regional Director will investigate and decide whether to pursue the allegation as a formal complaint. See NLRB, Investigate Charges, https://perma.cc/CU82-KU4V.6 If the parties do not settle and the Director formally pursues the complaint, the Director will issue notice of a hearing before an ALJ. Id.; 29 U.S.C. § 160(b); 29 C.F.R. § 101.10; Starbucks, 602 U.S. at 342-43.7 If necessary, after issuance of a complaint, the Board may seek temporary injunctive relief in federal district court while the dispute is pending at the NLRB. 29 U.S.C. § 160(j); Starbucks, 602 U.S. at 342. The ALJ then gathers evidence and presents “a proposed report, together with a recommended order to the Board.” 29 U.S.C. § 160(c). That order will become the order of the Board unless the parties file “exceptions.” Id.; 29 C.F.R. §§ 101.11-.12. If the parties file exceptions requesting the Board’s review, the Board will consider the ALJ’s recommendation, gather additional facts as necessary, and issue a decision. 29 U.S.C. § 160(c); 29 C.F.R. § 101.12. The Board may craft relief, such as a cease-and-desist order to halt unfair labor practices or an order requiring reinstatement of terminated employees. 29 U.S.C. § 160(c). These orders, however, are not independently enforceable; the Board must seek enforcement in a federal court of appeals (and may appoint attorneys to do so). Id. §§ 154, 160(e); In re NLRB, 304 U.S. 486, 495 (1938) (noting compliance with a Board order is not obligatory until entered as a decree by a court). Aside from adjudicating disputes, the Board may also conduct and certify the outcome of union elections, 29 U.S.C. § 159, and promulgate rules and regulations to carry out its statutory duties, id. § 156.

Although both the Board members and the GC are appointed by the President with “advice and consent” from the Senate, id. §§ 153(a), (d), only the Board is protected from removal at-will by the President, who is authorized to remove a Board member “upon notice and hearing, for neglect of duty or malfeasance in office, but for no other cause,” id. § 153(a). Such restrictions were intentional; much like many other multimember entities, the Board was designed to be an independent panel of experts that could impartially adjudicate disputes. See 29 U.S.C. § 153(a); Kirti Datla & Richard L. Revesz, Deconstructing Independent Agencies (and Executive Agencies), 98 CORNELL L. REV. 76, 770-71 (2013) (describing the NLRB as a classic example of an agency designed to be independent). Board members serve staggered five-year terms, and the President is authorized to designate one board member as Chairman. 29 U.S.C. § 153(a). In practice, the Board is partisan-balanced based on longstanding norms, though such a balance is not statutorily mandated. See Brian D. Feinstein & Daniel J. Hemel, Partisan Balance with Bite, 118 COLUM. L. REV. 9, 54-55 (2018).

B. Factual Background

As set out in plaintiff’s complaint and statement of material facts, and undisputed by defendants, plaintiff Gwynne Wilcox was nominated by President Biden and confirmed by the U.S. Senate to a second five-year term as member of the NLRB in September 2023. Pl.’s Mot. for Expedited Summ. J. (“Pl.’s Mot.”), Statement of Material Facts (“Pl.’s SMF”) ¶ 2, ECF No. 10-1; Defs.’ Cross-Mot. for Summ. J. and Opp’n to Pls.’ Mot. for Summ. J., Statement of Undisputed Material Facts (“Defs.’ SUMF”) ¶ 2, ECF No. 23-2. She was designated Chair of the Board in December 2024. Complaint ¶ 12, ECF No. 1.

Shortly after taking office, President Trump moved Marvin Kaplan, a then-sitting Board member and a defendant in this case, into the position of Chair, replacing plaintiff. Id. ¶ 13. President Trump then, on January 27, 2025, terminated plaintiff from her position on the Board via an email sent shortly before 11:00 PM, by the Deputy Director of the White House Presidential Personnel Office. Pl.’s Decl., Ex. A, ECF No. 10-4; Pl.’s SMF ¶ 3; Defs.’ SUMF ¶ 3. The termination was not preceded by “notice and hearing,” nor was any “neglect of duty or malfeasance” identified, despite the explicit restrictions to removal of a Board member in the NLRA. Pl.’s Decl. ¶¶ 3-4; Pl.’s SMF ¶¶ 4-5; Defs.’ SUMF ¶ 5 (regarding lack of notice and hearing); Motions H’rg (Mar. 5, 2025), Rough Tr. at 51:10-17. The email instead cited only political motivations—that plaintiff does not share the objectives of the President’s administration—and asserted, in a footnote, that the restriction on the President’s removal authority is unconstitutional as “inconsistent with the vesting of the executive Power in the President.” Pl.’s Decl. ¶ 3; Ex. A.

The NLRB’s Director of Administration, who reports directly to Mr. Kaplan, began the termination process, cutting off plaintiff’s access to her accounts and instructing her to clean out her office. Pl.’s Decl. ¶¶ 5-6. The Board already had two vacancies, and now, without plaintiff, it is reduced to only two sitting members—one short of the three-member quorum required to operate. [!!!] Compl. ¶ 18; 29 U.S.C. § 153(b). Removal of plaintiff has thus stymied the functioning of the Board.

Plaintiff filed the instant suit, challenging her removal and requesting injunctive relief against Mr. Kaplan so that she may resume her congressionally mandated role. See Compl. ¶¶ 21-22. Recognizing that this case involves a pure question of law, plaintiff moved for expedited summary judgment, on February 10, 2025, Pl.’s Mot., ECF No. 10, and defendants responded with a cross-motion for summary judgment, with briefing completed on a condensed schedule. See Defs.’ Cross-Mot. for Summ. J. and Opp’n to Pls.’ Mot. for Summ. J. (“Defs.’ Opp’n”), ECF No. 23; Pl.’s Opp’n to Defs.’ Cross-Mot. and Reply in Supp. of Mot. for Summ. J. (“Pl.’s Reply”), ECF No. 27; Defs.’ Reply in Supp. of Cross-Mot. for Summ. J. (“Defs.’ Reply”), ECF No. 30. Interested parties also weighed in as amici.8 Following a hearing, held on March 5, 2025, the parties’ cross-motions for summary judgement are ready for resolution.

II. LEGAL STANDARD

Summary judgment shall be granted “if the movant shows that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.” FED. R. CIV. P. 56(a). A fact is only “‘material’ if a dispute over it might affect the outcome of a suit under the governing law; factual disputes that are ‘irrelevant or unnecessary’ do not affect the summary judgment determination.” Holcomb v. Powell, 433 F.3d 889, 895 (D.C. Cir. 2006) (quoting Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986)). The dispute is only “genuine” if “the evidence is such that a reasonable jury could return a verdict for the non-moving party.” Id. (quoting Anderson, 477 U.S. at 248).

A plaintiff “seeking a permanent injunction . . . must demonstrate: (1) that it has suffered an irreparable injury; (2) that remedies available at law, such as monetary damages, are inadequate to compensate for that injury; (3) that, considering the balance of hardships between the plaintiff and defendant, a remedy in equity is warranted; and (4) that the public interest would not be disserved by a permanent injunction.” Monsanto Co v. Geertson Seed Farms, 561 U.S. 139, 156-57 (2010) (quoting eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388, 391 (2006)).

III. DISCUSSION

In the ninety years since the NLRB’s founding, the President has never removed a member of the Board. Pl.’s Mem. in Supp. of Pl.’s Mot. (“Pl.’s Mem.”) at 4, ECF No. 10-2. His attempt to do so here is blatantly illegal, and his constitutional arguments to excuse this illegal act are contrary to Supreme Court precedent and over a century of practice. For the reasons explained below, plaintiff’s motion is granted. Plaintiff’s termination from the Board was unlawful, and Mr. Kaplan and his subordinates are ordered to permit plaintiff to carry out all of her duties as a rightful, presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed member of the Board.

A. Humphrey’s Executor and its Progeny are Binding on this Court.

The Board is a paradigmatic example of a multimember group of experts who lead an independent federal office. Since the early days of the founding of this country, Congress, the President, and the Supreme Court all understood that Congress could craft executive offices with some independence, as a check on presidential authority. That understanding has not changed over the 150-year history of independent, multimember commissions, nor over the 90-year history of the NLRB. The Supreme Court recognized this history and tradition in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602 (1935), in upholding removal protections for such boards or commissions, and this precedent remains not only binding law, but also a well-reasoned reflection of the balance of power between the political branches sanctioned by the Constitution.

1. Removal Restrictions on Board Members are Well-Grounded in History and Binding Precedent.

As a textual matter, the Constitution is silent as to removals. See In re Hennen, 38 U.S. 230, 258 (1839). Consequently, though Article II grants the President authority over some appointments—with advice and consent of the Senate—and vests in him the “executive power,” Article II contains no express authority from which to infer an absolute removal power. Compare U.S. CONST. art. II, § 1, cl. 1 (vesting clause), and id., § 2, cl. 2 (appointments clause); to id. art. I, § 8, cl. 18 (clause granting Congress the authority “to make all laws” “necessary and proper” for carrying out its powers and “all other Powers vested . . . in the Government”). The Supreme Court has held that a general power to remove executive officers can be inferred from Article II, see Myers, 272 U.S. at 163-64, yet the contours of that removal power and the extent to which Congress may impose constraints are nowhere clearly laid out.

The courts in such cases must therefore turn to established precedent—judicial decisions as well as general practice and tradition. The Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized that “‘traditional ways of conducting government . . . give meaning’ to the Constitution.” Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361, 401 (1989) (alteration in original) (quoting Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 610 (1952) (Frankfurter, J., concurring)). Thus, “[ i]n separation-of-powers cases this Court has often ‘put significant weight upon historical practice.’” Zivotofsky, 576 U.S. at 23 (quoting Noel Canning, 573 U.S. at 524). Even when the validity of a particular power is in question, the Court will, “in determining the . . . existence of [that] power,” give weight to “the usage itself,” United States v. Midwest Oil Co., 236 U.S. 459, 473 (1915), and “hesitate to upset the compromises and working arrangements that the elected branches of Government themselves have reached,” Noel Canning, 573 U.S. at 526. Justice Frankfurter in his seminal concurring opinion in Youngstown declared that “systematic, unbroken” practice could even “be treated as a gloss on ‘executive Power’ vested in the President.” 343 U.S. at 610-11.

Not only are the removal protections on members of the independent, multimember boards like the NLRB supported by over a century of unbroken practice, but they have also been expressly upheld in clear Supreme Court precedent. Since 1887, Congress has created multiple independent offices led by panels whose members are appointed by the President but removable only for cause. See, e.g., Interstate Commerce Act, Pub. L. No. 49-41, ch. 104, § 11, 24 Stat. 379, 383 (1887) (creating the Interstate Commerce Commission, with restrictions on officers’ removal except for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance”); Federal Reserve Act, Pub. L. No. 63-64, ch. 6, § 10, 38 Stat. 251, 260-61 (1913) (creating the Federal Reserve Board, whose members are removable only “for cause”). In 1914, Congress established the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) with an “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office” removal restriction for its five commissioners. FTC Act, Pub. L. No. 63-203, ch. 311, § 1, 38 Stat. 717, 717-18 (1914).

The Supreme Court explicitly upheld removal restrictions for such boards when considering removal protections for the commissioners of the FTC in Humphrey’s Executor in 1935, while also recognizing the President’s general authority over removal of executive branch officials. The Court noted that commissioners of the FTC, “like the Interstate Commerce Commission” “are called upon to exercise the trained judgment of a body of experts ‘appointed by law and informed by experience.’” Id. at 624 (quoting Ill. Cent. R.R. Co. v. Interstate Com. Comm’n, 206 U.S. 441, 454 (1907)). Congress, having the power to create such expert commissions with quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial authority, must also have, “as an appropriate incident, power to fix the period during which they shall continue, and to forbid their removal for except for cause in the meantime.” Id. at 629.

Two months later, with the guidance supplied in Humphrey’s Executor and following the model of the FTC as endorsed by the Supreme Court there, Congress established the National Labor Relations Board. See Madden, supra, at 572-73; Yapp USA Auto. Sys., Inc. v. NLRB, --F. Supp. 3d--, No. 24-cv-12173, 2024 WL 4119058, at *5 (E.D. Mich. Sep. 9, 2024). Both entities—the FTC and NLRB—have five-member leadership boards with staggered terms of several years, minimizing instability and allowing for expertise to accrue. See 29 U.S.C. § 153(a); Seila L. LLC v. Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, 591 U.S. 197, 216 (2020). Both were intended to exercise impartial judgment. See Datla & Revesz, supra, at 770-71 (describing independence of the NLRB); Seila L., 591 U.S. at 215-16 (describing the FTC as “designed to be ‘non-partisan’ and ‘to act with entire impartiality’” (quoting Humphrey’s Ex’r, 295 U.S. at 624)). The Board, like the FTC, is “predominately quasi judicial and quasi legislative” in nature, with the primary responsibility of impartially reviewing decisions made by ALJs. Humphrey’s Ex’r, 292 U.S. at 624; see 29 U.S.C. § 160. In fact, the Board does not prosecute labor cases nor enforce its rulings. The side of the NLRB managed by the General Counsel—who is removable at-will by the President—carries out those more “executive” powers. See 29 U.S.C. § 153(d) (describing the General Counsel’s “final authority, on behalf of the Board” over “the investigation of charges and issuance of complaints . . . and . . . the prosecution of such complaints before the Board”). As plaintiff correctly states, the Board closely resembles the FTC and is thus “squarely at the heart of the rule adopted in Humphrey’s Executor.” Pl.’s Mem. at 9.

Numerous other offices have followed the mold of the NLRB and FTC with multimember independent leadership boards protected from at-will removal by the President. See Pl.’s Mem. at 7 n.2 (listing, e.g., the Merit Systems Protection Board, 5 U.S.C. § 1202(d); the Federal Labor Relations Authority, 5 U.S.C. § 7104(b); and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, 42 U.S.C. § 7171(b)(1)). “Since the Supreme Court's decision in Humphrey’s Executor, the constitutionality of independent [multimember] agencies, whose officials possess some degree of removal protection that insulates them from unlimited and instantaneous political control, has been uncontroversial.” Leachco, Inc. v. Consumer Prod. Safety Comm’n, 103 F.4th 748, 760 (10th Cir. 2024), cert. denied No. 24-156, 2025 WL 76435 (U.S. Jan. 13, 2025); see also The Pocket Veto Case, 279 U.S. 655, 689 (1929) (“Long settled and established practice is a consideration of great weight in a proper interpretation of constitutional” issues of separation of powers.).9

Recent consideration of the constitutionality of the removal protections for NLRB members have accordingly upheld those constraints on presidential removal authority under Humphrey’s Executor. See, e.g., Overstreet v. Lucid USA Inc., No. 24-cv-1356, 2024 WL 5200484, at *10 (D. Ariz. Dec. 23, 2024); Company v. NLRB, No. 24-cv-3277, 2024 WL 5004534, at *6 (W.D. Mo. Nov. 27, 2024); Kerwin v. Trinity Health Grand Haven Hosp., No. 24-cv-445, 2024 WL 4594709, at *7 (W.D. Mich. Oct. 25, 2024); Alivio Med. Ctr. v. Abruzzo, No. 24-cv-2717, 2024 WL 4188068, at *9 (N.D. Ill. Sep. 13, 2024); YAPP USA Automotive Sys., 2024 WL 4119058, at *7. Courts have also recently upheld restrictions on removal under Humphrey’s Executor for other multimember boards, such as the Consumer Product Safety Commission (“CPSC”). See, e.g., Leachco, 103 F.4th at 761-62; Consumers’ Rsch. v. CPSC, 91 F.4th 342, 352 (5th Cir. 2024); United States v. SunSetter Prods. LP, No. 23-cv-10744, 2024 WL 1116062, at *4 (D. Mass. Mar. 14, 2024). The same has been true for the FTC. See, e.g., Illumina, Inc. v. FTC, 88 F.4th 1036, 1046-47 (5th Cir. 2023); Meta Platforms, Inc. v. FTC, 723 F. Supp. 3d 64, 87 (D.D.C. 2024). A court in this district has also upheld removal protections for the Merit Systems Protection Board. See Harris v. Bessent, No. 25-cv-412 (RC), 2025 WL 679303, at *7 (D.D.C. Mar. 4, 2025). The 150-year history and tradition of multimember boards or commissions and 90-year precedent from the Supreme Court approving of removal protections for their officers dictates the same outcome for the NLRB here.

2. Defendants’ Argument that Humphrey’s Executor Does Not Control Fails.

Discounting this robust history, defendants posit that the President’s removal power is fundamentally “unrestricted” and that only two, narrow “exceptions” have been recognized: one for “inferior officers with narrowly defined duties,” as established in Morrison v. Olson, 487 U.S. 654 (1988), and the other for “multimember bod[ies] of experts, balanced along partisan lines, that performed legislative and judicial functions and [do not] exercise any executive power,” as established in Humphrey’s Executor. Defs.’ Opp’n at 5-6 (second passage quoting Seila L., 591 U.S. at 216). According to defendants, neither exception applies to the Board. Id. at 6. Putting aside to address later whether congressional authority to constrain the President’s removal authority is characterized fairly by defendants as a narrow “exception” to the rule of “unrestricted” removal power, see infra Part III.A.3.b, Humphrey’s Executor plainly controls.

Defendants emphasize that Humphrey’s Executor understood the FTC at the time not to exercise any “executive power,” which was key to its “exception,” and that the NLRB today clearly “wield[s] substantial executive power.” Defs.’ Opp’n at 6-8 (relying on Seila L., 591 U.S. at 216 n.2, 218); see also Defs.’ Reply at 3. They do not, however, meaningfully distinguish between the authority of the FTC in 1935, as recognized in Humphrey’s Executor, and the authority of the NLRB today. The FTC in 1935 had powers mimicking those of both the Board and the NLRB’s GC. The FTC had broad powers of investigation and could issue a complaint and hold a hearing for potential unfair methods of competition. See Humphrey’s Ex’r, 295 U.S. at 620, 621; see also 15 U.S.C. § 49 (authorizing the FTC’s subpoena power). The FTC, upon finding a violation, could issue a cease-and-desist order and then go to the Court of Appeals for enforcement. Humphrey’s Ex’r, 295 U.S. at 620-21; see also FTC Act, ch. 311, § 5, 38 Stat. at 719-20. The party subject to the order could also appeal to that court. Humphrey’s Ex’r, 295 U.S. at 621. Further, the FTC could issue rules and regulations regarding unfair and deceptive acts. See FTC Act, § 6, 38 Stat. at 722; Hon. R. E. Freer, Member of the FTC, Remarks on the FTC, its Powers and Duties at 2 (1940), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/docume ... welers.pdf.

The NLRB’s collective authority, though comparable, see supra Part I.A (describing the NLRB’s GC’s authority to investigate and pursue enforcement against unfair labor practices and the Board’s adjudicatory authority and power to issue unenforceable cease-and-desist orders), is, if anything, less extensive than that of the FTC. The NLRB hardly engages in rulemaking (other than to establish its own procedures), instead relying on adjudications for the setting of precedential guidance. See Allentown Mack Sales & Serv., Inc. v. NLRB, 522 U.S. 359, 374 (1998) (“The [NLRB], uniquely among major federal administrative agencies, has chosen to promulgate virtually all the legal rules in its field through adjudication rather than rulemaking.”). Moreover, the aspects of the NLRB’s authority most executive in nature—prosecutorial authority to investigate and bring civil enforcement actions—are tasks assigned to the GC instead of the Board itself. See 29 U.S.C. § 153(d).10

Even though the Supreme Court of 1935 may have not referred to these classic administrative powers as “executive” and the Supreme Court today would, see, e.g., Seila Law, 591 U.S. at 216 n.2, the substantive nature of authority granted to these two independent government entities does not significantly differ. If the Supreme Court has determined that removal restrictions on officers exercising substantially the same authority do not impermissibly intrude upon presidential authority, Humphrey’s Executor cannot be read to allow a different outcome here. That is especially true considering that the Supreme Court, in its next major decision addressing removal protections for executive branch officers, rejected the notion that the permissibility of “‘good cause’-type restriction[s] . . . turn[s] on whether or not th[e] official” is classified as “purely executive” or exercising quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial functions. See Morrison, 487 U.S. at 689.11

Defendants make a final, superficial distinction between the NLRB and the FTC to argue that the precedent of Humphrey’s Executor should not apply. Defs.’ Opp’n at 10. The NLRB, they note, has stricter removal protections because its members cannot be removed for “inefficiency,” whereas FTC members can. Id. In both Consumers’ Research, 91 F.4th at 346, 355-56, and Leachco, 103 F.4th at 761-63, however, courts of appeals upheld removal protections that did not include an exception for “inefficiency.” “Inefficiency” does not differ in substance from “neglect of duty,” so omitting “inefficiency” as a grounds for removal cannot be a dispositive difference in the President’s ability to exercise his Article II powers over the NLRB. See Jane Manners & Lev Menand, The Three Permissions: Presidential Removal and the Statutory Limits of Agency Independence, 121 COLUM. L. REV. 1, 8, 69 (2021) (explaining that the absence of “inefficiency” as a ground for removal does not unconstitutionally interfere with the President's authority). Defendants offer no reason to suggest otherwise. The NLRB fits well within the scope of Humphrey’s Executor.