United States District Court for the District of Columbia: National Council of Nonprofits, Plaintiffs, v. Office of Management and Budget, Defendants, Civil Action No. 25 - 239 (LLA); Memorandum Opinion and Order: "Defendants are enjoined from implementing, giving effect to, or reinstating under a different name the directives in OMB Memorandum M-25-13 with respect to the disbursement of Federal funds under all open awards

by USDC Judge Loren L. Alikhan

February 3, 2025

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF NONPROFITS, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET, et al.,

Defendants.

ORDERED that Defendants are enjoined from implementing, giving effect to, or reinstating under a different name the directives in OMB Memorandum M-25-13 with respect to the disbursement of Federal funds under all open awards; it is further

ORDERED that Defendants must provide written notice of the court’s temporary restraining order to all agencies to which OMB Memorandum M-25-13 was addressed. The written notice shall instruct those agencies that they may not take any steps to implement, give effect to, or reinstate under a different name the directives in OMB Memorandum M-25-13 with respect to the disbursement of Federal Funds under all open awards. It shall also instruct those agencies to release any disbursements on open awards that were paused due to OMB Memorandum M-25-13; it is further

ORDERED that this Order shall apply to the maximum extent provided for by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65(d)(2) and 5 U.S.C. §§ 705 and 706.

Civil Action No. 25 - 239 (LLA)

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

This matter is before the court on Plaintiffs’ Motion for a Temporary Restraining Order, ECF No. 5, and Defendants' Motion to Dismiss, ECF No. 21. Upon consideration of the parties’ briefs, oral argument, and for the reasons explained below, the court grants Plaintiffs' motion, denies Defendants’ motion, and enters a temporary restraining order against Defendants pursuant to the terms outlined at the end of this order.

I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY

A. Office of Management and Budget Memorandum M-25-13

On January 27, 2025, Matthew J. Vaeth, Acting Director of the Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”), issued a memorandum (“M-25-13”) directing federal agencies to “complete a comprehensive analysis of all of their Federal financial assistance programs to identify programs, projects, and activities that may be implicated by any of the President’s executive orders.” ECF No. 1 ¶ 15. The memorandum further stated that, “[ i]n the interim, to the extent permissible under applicable law, Federal agencies must temporarily pause all activities related to [the] obligation or disbursement of all Federal financial assistance, and other relevant agency acti[vities] that may be implicated by the executive orders, including, but not limited to, financial assistance for foreign aid, nongovernmental organizations, DEI, woke gender ideology, and the green new deal.” Id. ¶ 16; Off. of Mgmt. & Budget, Exec. Off. of the President, Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs (Jan. 27, 2025), https://perma.cc/69QB-VFG8 (“OMB Pause Memorandum”).

The memorandum defined “Federal financial assistance” as: “(i) all forms of assistance listed in paragraphs (1) and (2) of the definition of this term at 2 [C.F.R. §] 200.1; and (ii) assistance received or administered by recipients or subrecipients of any type except for assistance received directly by individuals.” Id. ¶ 17. This includes all federal assistance in the form of grants, loans, loan guarantees, and insurance. Id. ¶ 18; see 2 C.F.R. § 200.1. As relevant executive orders, it listed:

▪ Protecting the American People Against Invasion (Jan. 20, 2025);

▪ Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid (Jan. 20, 2025);

▪ Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements (Jan. 20, 2025);

▪ Unleashing American Energy (Jan. 20, 2025);

▪ Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing (Jan. 20, 2025);

▪ Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government (Jan. 20, 2025); and

▪ Enforcing the Hyde Amendment (Jan. 24, 2025).

OMB Pause Memorandum, at 1-2.

The memorandum stated that “[t]he temporary pause [would] become effective on January 28, 2025 at 5:00 PM.” Id. at 2. During the pause, agencies were directed to “submit to OMB detailed information on any programs, projects[,] or activities subject to [the] pause” on or before February 10, 2025. Id. at 2.

B. Complaint, Emergency Hearing, and Administrative Stay

Shortly after noon on January 28, several coalitions of nonprofit organizations brought this action against OMB and Acting Director Vaeth arguing that OMB’s action violated the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”), 5 U.S.C. § 701 et seq. ECF No. 1. Plaintiffs alleged that the implicated federal grants and funding “are the lifeblood of operations and programs for many . . . nonprofits, and [that] even a short pause in funding . . . could deprive people and communities of their life-saving services.” Id. ¶ 32. They argue that Defendants’ action was arbitrary and capricious, violated the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, and exceeded OMB’s statutory authority. Id. ¶¶ 43-61.

Along with their complaint, Plaintiffs sought a temporary restraining order (“TRO”) “barring the OMB and all of its officers, employees, and agents from taking any steps to implement, apply, or enforce Memo M-25-13.” ECF No. 5, at 18. Defendants entered an appearance, ECF No. 9, and the court held an emergency hearing at 4:00 p.m. on January 28 to discern the parties’ positions with respect to the issuance of a brief administrative stay pending the resolution of Plaintiffs’ request for a TRO, Minute Order (D.D.C. Jan. 28, 2025).

Given the extreme time constraints of the litigation and the magnitude of the legal issues, the court entered a brief administrative stay to permit the parties to fully brief the TRO motion and “buy[] the court time to deliberate.”1 ECF No. 13, at 3 (quoting United States v. Texas, 144 S. Ct. 797, 798 (2024) (Barrett, J., concurring)). The administrative stay prohibited Defendants “from implementing OMB Memorandum M-25-13 with respect to the disbursement of Federal funds under all open awards” until 5:00 p.m. on February 3, 2025. Id. at 4-5. The court also set a hearing on Plaintiffs’ TRO motion for 11:00 a.m. on February 3, 2025. Id. at 5.

C. Rescission of Memorandum M-25-13 and Aftermath

On January 29, the day after the court entered its administrative stay, OMB issued a new memorandum (“M-25-14”) that purported to rescind M-25-13. See ECF Nos. 18, 18-1. The new memorandum consisted of two sentences: “OMB Memorandum M-25-13 is rescinded. If you have questions about implementing the President’s Executive Orders, please contact your agency General Counsel.” ECF No. 18-1.

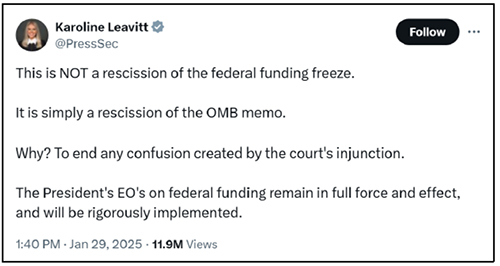

Shortly after this “rescission” was issued, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt announced from her official social media account that the new memorandum was “NOT a rescission of the federal funding freeze.” Karoline Leavitt, X (formerly Twitter) (Jan. 29, 2025), https://perma.cc/99C4-5V6G. Instead, she stated that “[ i]t [was] simply a rescission of [OMB memorandum M-25-13].” Id. She further explained that the purpose of the rescission was “[t]o end any confusion created by the court’s injunction.” Id. The entire post may be viewed below:

Karoline Leavitt

@PressSec

This is NOT a rescission of the federal funding freeze.

It is simply a rescission of the OMB memo.

Why? To end any confusion created by the court's injunction.

The President's EO's on federal funding remain in full force and effect, and will be rigorously implemented.

11:40 AM · Jan 29, 2025

Id.

On January 30, Defendants filed their opposition to Plaintiffs’ TRO motion and concurrently moved to dismiss the complaint for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. ECF Nos. 20, 21. As of February 1, both motions were fully briefed. ECF Nos. 24, 25, 26.

D. Temporary Restraining Order Hearing

On the morning of February 3, 2025, the court held a hearing on Plaintiffs’ motion for a TRO. See Minute Entry, (D.D.C. Feb. 3, 2025). At the conclusion of the hearing, the court explained that it was inclined to grant a TRO and deny Defendants’ motion to dismiss. Oral Argument, Nat’l Council of Nonprofits v. Off. of Mgmt. & Budget, No. 25-CV-239 (D.D.C. Feb. 3, 2025). Pursuant to the court’s request, Plaintiffs submitted a proposed TRO order shortly after the hearing concluded, and Defendants responded to the proposed order by mid-afternoon.

E. Parallel Litigation in the District of Rhode Island

On the same day Plaintiffs filed this suit, and several hours before memorandum M-25-13’s pause was to go into effect, twenty-two states and the District of Columbia filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Rhode Island and sought a TRO to halt implementation of the memorandum. See Compl., New York v. Trump, No. 25-CV-39 (D.R.I. Jan. 28, 2025), ECF No. 1. The district court scheduled a hearing for January 29 at 3:00 p.m.

Following the hearing, which took place after OMB had “rescinded” memorandum M-25-13, the court granted the States’ request and issued a TRO on January 31, 2025. TRO, New York, No. 25-CV-39 (D.R.I. Jan. 31, 2025), ECF No. 50. The restraining order prohibited the defendants (President Trump, OMB, and eleven federal agencies) from “paus[ing], freez[ing], imped[ing], block[ing], cancel[ing], or terminat[ing] [their] compliance with awards and obligations to provide federal financial assistance to the [plaintiff] States.” Id. at 11. The order also prohibited the defendants “from reissuing, adopting, implementing, or otherwise giving effect to the [OMB memorandum M-25-13] under any other name or title, . . . such as the continued implementation identified by the White House Press Secretary’s statement of January 29, 2025.” Id. at 12. Finally, the court directed the plaintiff States to file their forthcoming motion for a preliminary injunction expeditiously. Id. at 11.

On the morning of February 3, the defendants filed a notice of compliance with the court’s TRO. Notice of Compliance with Court’s TRO, New York, No. 25-CV-39 (D.R.I. Feb. 3, 2025), ECF No. 51. In it, the defendants explained that they had provided written notice to all defendant agencies on January 31 to inform them of the TRO and instruct them to comply with its restrictions. Id. ¶ 1. The defendants also notified the court that they believed certain terms of the TRO “constitute[d] significant intrusions on the Executive Branch’s lawful authorities and the separation of powers.” Id. ¶ 2.

The litigation remains ongoing.

II. DISCUSSION

A. Jurisdiction

Before reaching the merits, Defendants raise two threshold jurisdictional arguments. First, they argue that Plaintiffs lack standing because they have not adequately alleged injury in fact, causation, or redressability. ECF No. 21-1, at 7-11. Second, they claim that the case is now moot because OMB rescinded memorandum M-25-13 after Plaintiffs filed suit. Id. at 6. The court is unpersuaded on both counts.

1. Standing

A plaintiff seeking relief in federal court must establish standing by showing: (1) that it suffered an injury in fact, which is a concrete and particularized harm that is actual or imminent, rather than hypothetical, (2) a causal connection between the injury and the challenged conduct that is fairly traceable to the defendant’s actions, and (3) a non-speculative likelihood that the injury will be redressed by a decision in the plaintiff’s favor. Lujan v. Defs. of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560-61 (1992). Standing is “assessed as of the time a suit commences,” meaning that post-complaint events will not deprive a plaintiff of standing. Chamber of Commerce of the U.S. v. EPA, 642 F.3d 192, 200 (D.C. Cir. 2011). Defendants argue that Plaintiffs fail to satisfy all three elements of standing. The court disagrees.

a. Injury in fact

When a plaintiff association tries to sue on behalf of its members, it must demonstrate that: “(a) its members would otherwise have standing to sue in their own right; (b) the interests it seeks to protect are germane to the organization’s purpose; and (c) neither the claim asserted nor the relief requested requires the participation of individual members in the lawsuit.”2 Metro. Wash. Chapter, Associated Builders & Contractors, Inc. v. District of Columbia, 62 F.4th 567, 572 (D.C. Cir. 2023) (quoting Hunt v. Wash. State Apple Advert Comm’n, 432 U.S. 333, 343 (1977)). When facing a motion to dismiss, an association plaintiff “need only make a plausible allegation of facts establishing each element of standing.” Cutler v. U.S. Dep’t of Health & Hum. Servs., 797 F.3d 1173, 1179 (D.C. Cir. 2015).

Defendants claim that Plaintiffs have failed to “identif[y] a single member who . . . would be injured,” ECF No. 21-1, at 9 (quoting Chamber of Commerce, 642 F.3d at 200), but that is incorrect. Plaintiffs allege that even a temporary pause in funding to their members, such as the American Public Health Association and Main Street Alliance, would destroy their ability to provide medical and low-income childcare services. ECF No. 1 ¶¶ 33-34, 36-40. On top of these economic injuries, Plaintiffs’ members face First Amendment harms because the memorandum targets funds that relate to “DEI [and] woke gender ideology.” OMB Pause Memorandum, at 2; ECF No. 1 ¶¶ 35-36, 42. Defendants reply that Plaintiffs “must present more than allegations of a subjective chill” and need to allege “present objective harm or a threat of specific future harm.” ECF No. 26, at 3 (quoting Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S. 809, 816-17 (1975)). At this early stage, Plaintiffs have done exactly that: they claim that Defendants have singled out their funding programs (in other words, their economic lifelines) based on their exercise of speech and association.

Defendants further argue that a temporary pause would be far too brief to cause lasting damage, but the record belies these claims. First, Defendants have no factual basis on which to build such a counterargument. The pause outlined in memorandum M-25-13 is effectively indefinite with no clear parameters for when it will end. OMB Pause Memorandum, at 2. Second, Plaintiffs have provided numerous declarations showing that many organizations need weekly injections of federal funds in order to continue operating.3 One health center pays its employees “biweekly, on Thursdays,” requiring it to “draw down grant funds on the preceding Tuesday” so that they reach the health center’s bank account by Wednesday. ECF No. 24-4 ¶ 6. Some of those employees “live paycheck to paycheck,” meaning that a single missed payment could prevent them from buying groceries or paying rent. Id. ¶ 7. Separately, a member of a tribal organization was forced to lay off two employees on January 28 because it could not access its grant funds that day. ECF No. 24-5 ¶ 13. And another nonprofit dedicated to ending homelessness was forced to suspend a birth certificate and identification card program just so that it could keep its employees on payroll. ECF No. 24-7 ¶ 20-21.

Defendants also speculate that, at least for some organizations, OMB may have pre-approved certain programs so as to prevent any interruption in disbursements. Unfortunately for Defendants, the precise opposite appears to be true. According to Plaintiffs’ declarations, many organizations were blocked from accessing their funds well before 5:00 p.m. on January 28, when the freeze was set to begin. See, e.g., ECF Nos. 24-4 ¶ 8 (unable to access fund portal during the day on January 28); 24-7 ¶ 13 (same); 24-8 ¶ 9 (unable to access fund portal on January 27).

The alleged injuries to Plaintiffs’ many members are sufficiently concrete and imminent to satisfy the first element of standing. For many, the harms caused by the freeze are non-speculative, impending, and potentially catastrophic. Defendants’ assertion that these injuries are nothing more than “a setback to [Plaintiffs’] abstract social interests,” ECF No. 26, at 3-4 (quoting Food & Drug Admin. v. Alliance for Hippocratic Med., 602 U.S. 367, 394 (2024)), is blatantly contradicted by the record. Plaintiffs have adequately shown injury in fact.

b. Causation

Defendants next try to break the causal chain between memorandum M-25-13 and Plaintiffs’ harms. Defendants argue that with the memorandum now rescinded, any lingering pauses in funding are not fairly traceable to the memorandum itself. Instead, they say, Plaintiffs must take up their grievances with the individual agencies responsible for disbursing their funds. ECF Nos. 21-1, at 10-11; 26, at 5-7.

At a high level, Defendants are correct that harms caused by third parties are generally not traceable to the defendant. See Fla. Audubon Soc’y v. Bentsen, 94 F.3d 658, 664 (D.C. Cir. 1996) (en banc) (explaining that traceability must be to “the challenged acts of the defendant, not of some absent third party”). And where causation “hinge[s] on the independent choices of [a] regulated third party,” like the states or other federal actors, it is the plaintiff’s burden “to adduce facts showing that those choices have been or will be made in such manner as to produce causation.” Ctr. for L. & Educ. v. Dep’t of Educ., 396 F.3d 1152, 1161 (D.C. Cir. 2005). Plaintiffs claim that memorandum M-25-13 “was not a suggestion but a command to agencies, and [the agencies] have treated it as such.” ECF No. 24, at 17. They further allege that their economic and constitutional harms stem directly from the memorandum’s directives, making OMB and Acting Director Vaeth the proper defendants. Id.

In their briefing, Defendants rely on two cases to make their counterargument. See ECF No. 21-1, at 10-11. In Louisiana ex rel. Landry v. Biden, 64 F.4th 674 (5th Cir. 2023), the Fifth Circuit held that an OMB working group’s “guidance” and publication of cost estimates did not confer standing on plaintiffs who sought to block its effects, id. at 681-82. As an initial matter, the Fifth Circuit’s ruling had nothing to do with the causation element of standing. The court only considered whether the “possibility of regulation” was an “injury in fact.” Id. (quoting Nat’l Ass’n of Home Builders v. EPA, 667 F.3d 6, 13 (D.C. Cir. 2011)). But even if the court were to extend its reasoning to causation, Defendants’ argument still fails. The executive order in Louisiana “d[id] not require any action from federal agencies.” Id. at 681. Agencies were not mandated to “implement the Interim Estimates” and could “exercise discretion” in choosing whether or not they applied. Id. In contrast, memorandum M-25-13 states in no uncertain terms (and in bold typeface, no less) that “Federal agencies must temporarily pause all activities related to [the] obligation or disbursement of all Federal financial assistance.” OMB Pause Memorandum, at 2. Such a directive leaves no room for discretion. Louisiana is therefore inapposite.

Defendants’ second case fares no better. In Jacobson v. Florida Secretary of State, 974 F.3d 1236 (11th Cir. 2020), voters sued to change the process by which gubernatorial candidates were listed on voting ballots, id. at 1242. The plaintiffs only named the Florida secretary of state as a defendant. Id. The Eleventh Circuit held that the plaintiffs could not show causation because nonparty “supervisors of elections”—not the secretary of state—determined the ballot order. Id. at 1253. But critical to the court’s ruling was the fact that the supervisors were “independent officials under Florida law who [were] not subject to the [s]ecretary’s control.” Id. Instead, they were “constitutional officers who [were] elected at the county level by the people of Florida.” Id. Suing the secretary was therefore futile because she exercised no executive, statutory, or other authority over the supervisors’ actions. Here, however, Defendants do not argue that OMB is powerless to dictate executive policy, nor could they (indeed, they try to argue the exact opposite). See 31 U.S.C. § 503 (establishing that OMB “[p]rovides overall direction and leadership to the executive branch on financial management matters by establishing financial management policies and requirements”); ECF No. 21-1, at 16-20. Unlike the secretary in Jacobson, OMB can exert some influence on federal spending policy (even though Plaintiffs dispute the extend of that authority). Its actions therefore give rise to causation in this case.

The record also supports Plaintiffs’ allegations of causation. On January 30, after this court’s administrative stay and OMB’s purported “rescission” of M-25-13, the Environmental Protection Agency responded to a nonprofit’s funding inquiry by saying that it was still “working diligently to implement [OMB]’s memorandum, Temporary Pause of Agency Grant, Loan, and Other Financial Assistance Programs.” ECF No. 24-1, at 7. The EPA further explained that it was “temporarily pausing all activities related to the obligation or disbursement of EPA Federal financial assistance at this time” and was “continuing to work with OMB” to do so. Id. The EPA’s statement that it was freezing funds in order to “implement” memorandum M-25-13 contradicts Defendants’ claim that continued pauses are only attributable to independent agency action. At oral argument, Defendants represented that as soon as they learned of EPA’s continued pause, they contacted the agency to correct any misunderstandings. Oral Argument, Nat’l Council of Nonprofits, No. 25-CV-239 (D.D.C. Feb. 3, 2025). In this early posture, however, and pending further factual development by the parties, the court relies on Plaintiffs’ post-rescission declarations to conclude that Plaintiffs have sufficiently alleged causation.

c. Redressability

Causation and redressability are closely related. While the former “focus[es] on whether a particular party is appropriate[,] redressability [considers] whether the forum is.” Bentsen, 94 F.3d at 664. In short, a plaintiff must demonstrate that the relief sought, if granted, “will likely alleviate the particularized injury alleged.” Id. at 663-64. Plaintiffs argue that blocking Defendants from doing anything to implement the substance of memorandum M-25-13 would remedy their harms. ECF No. 24, at 17-18.

Defendants respond by saying that blocking memorandum M-25-13 “would not prevent non-defendant agencies from exercising their own independent authorities to determine whether . . . a pause is warranted.” ECF No. 21-1, at 11. But, as discussed above, there is at least some evidence that agencies are pausing disbursements because of memorandum M-25-13. See supra Part II.A.1.b.

Prior to the issuance of memorandum M-25-13, Plaintiffs’ members reportedly never had problems drawing down funds or receiving financial assistance. ECF Nos. 24-4 ¶ 8; 24-5 ¶ 10. That all changed beginning January 28, immediately after OMB issued memorandum M-25-13. Streams of funds that had steadily flowed for years without issue suddenly ran dry. If the court were to grant Plaintiffs’ requested relief, Defendants would be barred from instructing all federal agencies across the board to temporarily pause (or continue pausing) financial assistance on the basis of the memorandum or its substance.4 In other words, agencies would need to behave as if the memorandum were never issued. Defendants act as if any continued freeze is merely a random coincidence that could not possibly have anything to do with their memorandum. In the court’s view, that explanation ignores both logic and fact. Plaintiffs have adequately shown that a ruling in their favor will alleviate their alleged injuries.

2. Mootness

Mootness concerns whether there is still a live controversy for the court to adjudicate. Courts often describe mootness as “the doctrine of standing set in a time frame.” U.S. Parole Comm’n v. Geraghty, 445 U.S. 388, 397 (1980) (quoting Henry P. Monaghan, Constitutional Adjudication: The Who and When, 82 Yale L.J. 1363, 1384 (1973)). Defendants characterize Plaintiffs’ complaint as only challenging OMB memorandum M-25-13. ECF No. 21-1, at 6. Therefore, in Defendants’ view, OMB’s post-complaint rescission of that memorandum eliminated the lawsuit’s only basis and mooted Plaintiffs’ claims. Id. This fails for several reasons.

First, it is blackletter law that a defendant’s “voluntary cessation of a challenged practice does not deprive a federal court of its power to determine [its] legality.” Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Env’t Servs. (TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 189 (2000) (quoting City of Mesquite v. Aladdin’s Castle, Inc., 455 U.S. 283, 289 (1982)). If voluntary cessation automatically mooted every case, a defendant would be “free to return to [its] old ways” as soon as the case was dismissed. Id. (quoting City of Mesquite, 455 U.S. at 289). Voluntary cessation can only deprive the court of jurisdiction if it is “absolutely clear [that] the allegedly wrongful behavior could not reasonably be expected to recur.” Pub. Citizen, Inc. v. Fed. Energy Reg. Comm’n, 92 F.4th 1124, 1128 (D.C. Cir. 2024) (emphasis added) (quoting Friends of the Earth, Inc., 528 U.S. at 189). This is a “heavy burden” for the party asserting mootness. Id.

Here, Defendants claim that they have ended any allegedly unlawful activity by retracting memorandum M-25-13. Even taking the rescission at face value, however, Defendants have not convincingly shown that they will refrain from “resum[ing] the challenged activity” in the future. Pub. Citizen, Inc., 92 F.4th at 1128. As evidenced by the White House Press Secretary’s statements, OMB and the various agencies it communicates with appear committed to restricting federal funding. If Defendants retracted the memorandum in name only while continuing to execute its directives, it is far from “absolutely clear” that the conduct is gone for good. There is nothing stopping OMB from rewording, repackaging, or reissuing the substance of memorandum M-25-13 if the court were to dismiss this lawsuit.

The voluntary cessation doctrine is especially important in cases where the defendant is suspected of “manipulating the judicial process through the false pretense of singlehandedly ending a dispute.” Pub. Citizen, Inc., 92 F.4th at 1128 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Guedes v. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms & Explosives, 920 F.3d 1, 15 (D.C. Cir. 2019) (per curiam)). Plaintiffs accuse Defendants of doing exactly that here. ECF No. 24, at 19-20.

Defendants understandably dispute this accusation. They protest that such a conclusion “would be contrary to the presumption of good faith that courts routinely accord the government when assessing voluntary cessation.” ECF No. 26, at 8 (citing Am. Cargo Transp., Inc. v. United States, 625 F.3d 1176, 1180 (9th Cir. 2010)). Defendants are correct that courts of this circuit generally hesitate “to impute such manipulative conduct to a coordinate branch of government.” Pub. Citizen, Inc., 92 F.4th at 1128-29 (quoting Clarke v. United States, 915 F.2d 699, 705 (D.C. Cir. 1990) (en banc)). But this reluctance does not apply when the government defendant deliberately acts “in order to avoid litigation.” Alaska v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric., 17 F.4th 1224, 1229 (D.C. Cir. 2021) (quoting Am. Bar Ass’n v. Fed. Trade Comm’n, 636 F.3d 641, 648 (D.C. Cir. 2011)). Here, Defendants’ plea for a presumption of good faith rings hollow when their own actions contradict their representations.

Within hours of OMB’s rescission, White House Press Secretary Leavitt announced that the rescission was to have no tangible effect on “the federal funding freeze.” Leavitt, X (formerly Twitter) (Jan. 29, 2025), https://perma.cc/99C4-5V6G. Moreover, she explained that the primary purpose of the rescission was “[t]o end any confusion created by the court’s injunction.” Id. That statement unambiguously reflects that the rescission was in direct response to this court’s issuance of an administrative stay on January 28.5 For Defendants to innocently claim that OMB’s post-stay actions were merely a noble attempt to “end[] confusion,” ECF No. 26, at 8, strains credulity. By rescinding the memorandum that announced the freeze, but “NOT . . . the federal funding freeze” itself, id., it appears that OMB sought to overcome a judicially imposed obstacle without actually ceasing the challenged conduct. The court can think of few things more disingenuous. Preventing a defendant from evading judicial review under such false pretenses is precisely why the voluntary cessation doctrine exists. The rescission, if it can be called that, appears to be nothing more than a thinly veiled attempt to prevent this court from granting relief.

Second, even if voluntary cessation did not apply, the facts on the ground indicate that this case is anything but moot. Even aside from the Press Secretary’s seeming admission that the pause will continue as planned, Plaintiffs have presented evidence that fund recipients continue to be deprived of critical loans, grants, and other resources. For example, the chief executive officer of a community health center stated that he was unable to access critical funds awarded under an H80 grant (authorized by the Public Health Service Act) starting on January 28. ECF No. 24-4 ¶ 10. After this court entered its administrative stay that afternoon, he was still unable to access funds the next day. Id. ¶ 11. And after OMB rescinded memorandum M-25-13 on January 29, he was still blocked from accessing grant funds as recently as January 31. Id. ¶ 12. Similarly, members of a tribal organization who were unable to draw down grant funds starting on January 28 had still not received any funds as recently as January 31. ECF No. 24-5 ¶ 24. And low-income parents who rely on federal grants to enable their children to attend childcare still had not received their subsidies as recently as January 31. ECF No. 24-11 ¶ 19; see, e.g., ECF Nos. 24-6, 24-7, 24-8, 24-9. Each of these examples indicates that the funding pause remains in effect—at least for some recipients—despite OMB’s rescission of memorandum M-25-13. Defendants cannot persuasively argue that the rescission of memorandum M-25-13 moots the case if the effects and directives of that memorandum continue to remain in full force. Destroying the paper trail of allegedly illegal activity means nothing if the activity persists.

In a last-ditch effort to toss the case on mootness grounds, Defendants argue that even if aspects of the funding freeze remain in effect, they persist independent of memorandum M-25-13 and thus must be challenged in a different lawsuit. ECF No. 26, at 9. In their view, just because some money is not “going out the door” does not necessarily mean that it is due to OMB’s action. Oral Argument, Nat’l Council of Nonprofits, No. 25-CV-239 (D.D.C. Feb. 3, 2025). To the extent that funds still remain paused in spite of this court’s administrative stay or the memorandum’s rescission, Defendants argue that those pauses are the result of independent agency discretion or the President’s executive orders.

This is essentially a slightly repackaged version of Defendants’ causation argument: with the memorandum now rescinded, any lingering pauses in funding are not fairly traceable to the memorandum itself. Insofar as this lawsuit challenges the memorandum, Defendants argue that that avenue to relief is now closed. But, as explained above, supra Part II.A.1.b. & n.4, the court is not persuaded that the continuing freezes are solely due to independent agency action. Both logic and record evidence point to the opposite conclusion. As Plaintiffs’ counsel noted at oral argument, it is unclear whether twenty-four hours is sufficient time for an agency to independently review a single grant, let alone hundreds of thousands of them. Oral Argument, Nat’l Council of Nonprofits, No. 25-CV-239 (D.D.C. Feb. 3, 2025).

With respect to the executive orders, which the parties discussed at length during oral argument, the court remains unconvinced. Defendants’ counsel cited provisions of the executive orders referenced in M-25-13 that purportedly required temporary pauses in funding. Id. It is true that at least some of the executive orders contain language that could be construed as requiring fund pauses (albeit on much more drawn out timelines than memorandum M-25-13). See Exec. Order No. 14,151, Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing, 90 Fed. Reg. 8339 (Jan. 20, 2025) (requiring all federal agencies to “terminate, to the maximum extent allowed by law, . . . ‘equity-related’ grants or contracts” within sixty days); Exec. Order No. 14,162, Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements, 90 Fed. Reg. 8455 (Jan. 20, 2025) (directing the United States Ambassador to the United Nations to “immediately cease or revoke any purported financial commitment made by the United States under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change”). But Plaintiffs have provided evidence that the scope of frozen funds appears to extend far beyond the reach of the executive orders, thus undermining Defendants’ claims.

As just one example, a health center that provides medical, dental, and behavioral health services to a rural community was denied access to grant funds. See ECF No. 24-4. None of the seven executive orders listed in memorandum M-25-13 would seem to cover such activity. See, e.g., Exec. Order No. 14,159, Protecting the American People Against Invasion, 90 Fed. Reg. 8443 (Jan. 20, 2025) (addressing illegal immigration); Exec. Order No. 14,169, Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid, 90 Fed. Reg. 8619 (Jan. 20, 2025) (addressing foreign aid); Exec. Order No. 14,162, Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements, 90 Fed. Reg. 8455 (Jan. 20, 2025) (addressing international environmental agreements); Exec. Order No. 14,154, Unleashing American Energy, 90 Fed. Reg. 8353 (Jan. 20, 2025) (addressing energy industry and regulations); Exec. Order No. 14,151, Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing, 90 Fed. Reg. 8339 (Jan. 20, 2025) (addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion programs); Exec. Order No. 14,168, Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government, 90 Fed. Reg. 8615 (Jan. 20, 2025) (addressing “gender ideology”); Exec. Order No. 14,182, Enforcing the Hyde Amendment, 90 Fed. Reg. 8751 (Jan. 24, 2025) (addressing federal funding of abortion). At oral argument, when asked about another declarant who was receiving a grant from the National Science Foundation, see ECF No. 24-7, Defendants could not give a clear answer as to why that recipient would be denied funds pursuant to the executive orders, Oral Argument, Nat’l Council of Nonprofits, No. 25-CV-239 (D.D.C. Feb. 3, 2025). In sum, the court agrees with Plaintiffs that rescinding memorandum M-25-13 did not moot the case.

* * *

For these reasons, the court concludes that it has jurisdiction over Plaintiffs’ complaint.