Memorandum Opinion and Order

Bennie Thompson, et al., v. Donald J. Trump

USDC for the District of Columbia

by Judge Amit P. Mehta

February 18, 2022

Librarian's Comment:

[T]he phrase Colour of his Office appears as early as the thirteenth century, in an English statute providing "[t]hat no Escheator, Sheriff, nor other Bailiff of the King, by Colour of his Office, without special Warrant, or Commandment, or Authority certain pertaining to his Office, disseise any Man of his Freehold, nor of any Thing belonging to his Freehold." In his annotation of the statute, Sir Edward Coke explained the statutory phrase Per colour de son office:Colore officii is ... a seisure unduly made against law. And he may do it colore officii in two manner of wayes: either when he hath no warrant at all, or when he hath a warrant, and doth not pursue it.

When the Reconstruction Congresses incorporated the phrase in the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1871, under color of was a well known legal expression with a long and distinguished pedigree. Not surprisingly, the meaning of the phrase had shifted subtly as it was deployed in different doctrinal contexts that reflected different policy concems. Still, the central idea conveyed by the phrase had remained remarkably constant for six centuries: Under color of law referred to official action without authority of law, in the nineteenth as in the thirteenth century. At page 325 – 327.

[T]he obvious import of under color of law is that the phrase refers to official action that seems to be lawful and authorized, but turns out not to be. At page 328

[T]he misconduct of an official differs qualitatively from a mere private wrong.As if an officer will take more for his fees than he ought, this is done colore officii sui, but yet it is not part of his office, and it is called extortion, . . . which is no other than robbery, but it is more odious than robbery, for robbery is apparent, and always hath the countenance of vice, but extortion, being equally as great a vice as robbery, carries the mask of virtue, and is more difficult to be tried or discerned, and consequently more odious than robbery.

Page 346, quoting Dive v. Maningham, 1 Plowden Rep. 60, 61-62, 75 Eng. Rep. 96, 97-99 (Common Bench 1551) (first reported in 1578).

-- Steven L. Winter, The Meaning of "Under Color of" Law, Michigan L.R. 91:323 (1992)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

BENNIE G. THOMPSON et al.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

DONALD J. TRUMP et al.,

Defendants.

Case No. 21-cv-00400 (APM)

ERIC SWALWELL,

Plaintiff,

v.

DONALD J. TRUMP et al.,

Defendants.

Case No. 21-cv-00586 (APM)

JAMES BLASSINGAME & SIDNEY HEMBY,

Plaintiffs,

v.

DONALD J. TRUMP,

Defendant.

Case No. 21-cv-00858 (APM)

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

I. INTRODUCTION

January 6, 2021 was supposed to mark the peaceful transition of power. It had been that way for over two centuries, one presidential administration handing off peacefully to the next. President Ronald Reagan in his first inaugural address described “the orderly transfer of authority” as “nothing less than a miracle.”1 Violence and disruption happened in other countries, but not here. This is the United States of America, and it could never happen to our democracy.

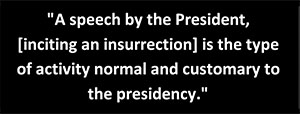

But it did that very afternoon. At around 1:30 p.m., thousands of supporters of President Donald J. Trump descended on the U.S. Capitol building, where Congress had convened a Joint Session for the Certification of the Electoral College vote. The crowd had just been at the Ellipse attending a “Save America” rally, where President Trump spoke. At the end of his remarks, he told rally-goers, “we fight, we fight like hell, and if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.” The President then directed the thousands gathered to march to the Capitol—an idea he had come up with himself. About 45 minutes after they arrived, hundreds of the President’s supporters forced their way into the Capitol building. Many overcame resistance by violently assaulting United States Capitol Police (“Capitol Police”) with their fists and with weapons. Others simply walked in as if invited guests. As Capitol Police valiantly fought back and diverted rioters, members of Congress adjourned the Joint Session and scrambled to safety. So, too, did the Vice President of the United States, who was there that day in his capacity as President of the Senate to preside over the Certification. Five people would die, dozens of police officers suffered physical and emotional injuries and abuse, and considerable damage was done to the Capitol building. But, in the end, after law enforcement succeeded in clearing rioters from the building, Congress convened again that evening and certified the next President and Vice President of the United States. The first ever presidential transfer of power marred by violence was over.

These cases concern who, if anyone, should be held civilly liable for the events of January 6th. The plaintiffs in these cases are eleven members of the House of Representatives in their personal capacities and two Capitol Police officers, James Blassingame and Sidney Hemby (“Blassingame Plaintiffs”). Taken together, they have named as defendants: President Trump; the President’s son, Donald J. Trump Jr.; the President’s counsel, Rudolph W. Giuliani; Representative Mo Brooks; and various organized militia groups—the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, and Warboys— as well as the leader of the Proud Boys, Enrique Tarrio.

Plaintiffs’ common and primary claim is that Defendants violated 42 U.S.C. § 1985(1), a provision of a Reconstruction-Era statute known as the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. The Act was aimed at eliminating extralegal violence committed by white supremacist and vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan and protecting the civil rights of freedmen and freedwomen secured by the Fourteenth Amendment. Section 1985(1) is not, however, strictly speaking a civil rights provision; rather, it safeguards federal officials and employees against conspiratorial acts directed at preventing them from performing their duties. It provides:

If two or more persons in any State or Territory conspire to prevent, by force, intimidation, or threat, any person from accepting or holding any office, trust, or place of confidence under the United States, or from discharging any duties thereof; or to induce by like means any officer of the United States to leave any State, district, or place, where his duties as an officer are required to be performed, or to injure him in his person or property on account of his lawful discharge of the duties of his office, or while engaged in the lawful discharge thereof, or to injure his property so as to molest, interrupt, hinder, or impede him in the discharge of his official duties.

42 U.S.C. § 1985(1). The statute, in short, proscribes conspiracies that, by means of force, intimidation, or threats, prevent federal officers from discharging their duties or accepting or holding office. A party injured by such a conspiracy can sue any coconspirator to recover damages. Id. § 1985(3).

Plaintiffs all contend that they are victims of a conspiracy prohibited by § 1985(1). They claim that, before and on January 6th, Defendants conspired to prevent members of Congress, by force, intimidation, and threats, from discharging their duties in connection with the Certification of the Electoral College and to prevent President-elect Joseph R. Biden and Vice President–elect Kamala D. Harris from accepting or holding their offices. More specifically, they allege that, before January 6th, President Trump and his allies purposely sowed seeds of doubt about the validity of the presidential election and promoted or condoned acts of violence by the President’s followers, all as part of a scheme to overturn the November 2020 presidential election. Those efforts culminated on January 6th, when the President’s supporters, including organized militia groups and others, attacked the Capitol building while Congress was in a Joint Session to certify the Electoral College votes. Notably, Plaintiffs allege that President Trump’s January 6 Rally Speech incited his supporters to commit imminent acts of violence and lawlessness at the Capitol. Plaintiffs all claim that they were physically or emotionally injured, or both, by the acts of the conspirators.

Plaintiffs advance other claims, as well. Swalwell alleges a violation of § 1986, a companion provision to § 1985. 42 U.S.C. § 1986. That statute makes a person in a position of power who knows about a conspiracy prohibited by § 1985, and who neglects or refuses to take steps to prevent such conspiracy, liable to a person injured by the conspiracy. Swalwell claims that President Trump, Trump Jr., Giuliani, and Brooks violated § 1986 by refusing to act to prevent the violence at the Capitol. Swalwell and the Blassingame Plaintiffs also advance numerous common law torts and statutory violations under District of Columbia law.

All Defendants have appeared except the Proud Boys and Warboys. Defendants have moved to dismiss all claims against them. They advance a host of arguments that, in the main, seek dismissal for lack of subject matter jurisdiction or for failure to state a claim. The parties have submitted extensive briefing on a range of constitutional, statutory, and common law issues. The court held a five-hour-long oral argument to consider them.

After a full deliberation over the parties’ positions and the record, the court rules as follows: (1) President Trump’s motion to dismiss is denied as to Plaintiffs’ § 1985(1) claim and certain District of Columbia–law claims and granted as to Swalwell’s § 1986 claim and certain District of Columbia–law claims; (2) Trump Jr.’s motion to dismiss is granted; (3) Giuliani’s motion to dismiss is granted; (4) the Oath Keepers’ motion to dismiss is denied; and (5) Tarrio’s motion to dismiss is denied. Separately, Brooks has moved to substitute the United States as the proper party under the Westfall Act. The court declines to rule on that motion and instead invites Brooks to file a motion to dismiss, which the court will grant for the same reasons it has granted Trump Jr.’s and Giuliani’s motions.

II. BACKGROUND

A. Facts Alleged

This summary of the alleged facts is drawn from the complaints in all three cases. There is substantial overlap, but there are some differences. The court has not referenced every fact alleged across the three complaints; this factual recitation is meant to summarize the main allegations. Additionally, a citation to one complaint should not be understood to mean that the allegation is not present in the other complaints. The court has limited the citations in the interest of efficiency. Additional facts will be referenced as appropriate in the Discussion section.

As is required on a motion to dismiss, the court assumes these facts to be “true (even if doubtful in fact).” Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 556 (2007). These are not the court’s factual findings.

1. The Weeks Following the Election

a. False claims of election fraud and theft

President Trump began to sow seeds of doubt about the validity of the November 2020 presidential election in the weeks leading up to Election Day. Am. Compl., Blassingame v. Trump, No. 21-cv-00858 (APM) (D.D.C.), ECF No. 3 [hereinafter Blassingame Compl.], ¶ 13. He claimed, among other things, that there would be “fraud,” the election was “rigged,” and his adversaries were “trying to steal” victory from him. Id. ¶¶ 13, 16; Compl., Swalwell v. Trump, No. 21-cv-00586 (APM) (D.D.C.), ECF No. 1 [hereinafter Swalwell Compl.]; Mot. for Leave to File Am. Compl., ECF No. 11, Am. Compl., ECF No. 11-1, [hereinafter, Thompson Compl.], ¶ 33.2

On election night, the President claimed victory before all the votes were counted. He tweeted that “they are trying to STEAL the Election. We will never let them do it.” Blassingame Compl. ¶ 17. He also would say in a primetime television address the next day, “If you count the legal votes, I easily win. If you count the illegal votes, they can try to steal the election from us.” Swalwell Compl. ¶ 33.

The President’s allies joined him in making similar claims. For example, on November 5, 2020, Brooks tweeted that he “lack[ed] faith that this was an honest election.” Id. ¶ 78. On November 6, 2021, Trump Jr. tweeted that his father’s campaign was uncovering evidence of voter fraud and that the media was creating a false narrative that voter fraud was not real. Id. ¶ 69. On November 7, 2020, one of President Trump’s lawyers, Rudolph Giuliani, held a press conference in suburban Philadelphia, during which he asserted that there was rampant voter fraud in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, which accounted for the President’s loss in Pennsylvania. Thompson Compl. ¶ 38.

b. Efforts to influence state and local election officials

The President also took his case directly to state and local election officials. These meetings occurred by phone and in person, and centered mostly on Georgia, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Swalwell Compl. ¶¶ 39, 45, 49, 52. In some instances, these efforts were followed by threatening words and conduct by some supporters.

In Georgia, for example, the President called Georgia’s Secretary of State an “enemy of the people” and tweeted about him over a dozen times. Swalwell Compl. ¶ 49. The Secretary and his family were then targeted by some of the President’s supporters with threats of violence and death. Id. ¶ 50. Another Georgia state official pleaded with the President to condemn death threats made to election workers in Georgia, but he refused to do so. Blassingame Compl. ¶ 29.

In another instance, in Michigan, on December 5, 2020, the President falsely declared that he had won almost every county in the state. Swalwell Compl. ¶ 40. The next day armed protesters went to the home of Michigan’s Secretary of State, demanding she overturn the election results. Thompson Compl. ¶ 50. During these weeks, the President also tweeted criticism of Republican governors in Arizona and Georgia, claiming that “[ i]f they were with us, we would have already won both.” Swalwell Compl. ¶ 36.

During these efforts, and aware of the threats directed against state election officials, the President tweeted, “People are upset, and they have a right to be.” Thompson Compl. ¶ 52.

The President’s allies, including Brooks and Giuliani, continued to support the President’s campaign to undo the election results. Brooks, for example, tweeted false claims that President-elect Joe Biden had not won Georgia, and he also announced that he would object to certifying the Electoral College ballots from Georgia. Swalwell Compl. ¶ 82. Giuliani also continued his efforts, falsely suggesting in mid-November that irregularities in Detroit were the reason for the President’s loss. Thompson Compl. ¶ 42. He asked then–Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security Ken Cuccinelli to seize voting machines. Swalwell Compl. ¶ 62. A Trump campaign attorney even suggested that an election official should be shot. Thompson Compl. ¶ 48.

c. “Stop the Steal” rallies

Dozens of protests sprung up around the country. Blassingame Compl. ¶ 22. Two in Washington, D.C., turned violent. On the evening of November 14, 2020, multiple police officers were injured and nearly two dozen arrests were made. Id. ¶ 26. Then, on December 12, 2020, supporters of the President clashed with District of Columbia police, injuring eight of them, which led to over 30 arrests, many for acts of assault. Id. ¶ 28. The President was aware of these rallies, as he tweeted about them, and he would have known about the violence that accompanied them. Id. ¶¶ 25, 27.

Organized militia groups attended these events in Washington, D.C. One of them was the Proud Boys. During a pre-election debate, the moderator asked whether President Trump would denounce white supremacist groups. When the President asked, “[W]ho would you like me to condemn?,” Vice President Biden suggested the “Proud Boys,” to which the President responded, “Proud Boys, stand back, and stand by.” Thompson Compl. ¶ 30. Tarrio, the head of the Proud Boys, tweeted in response, “Standing by sir.” Id.

Another militia group that came to Washington, D.C., for these rallies was the Oath Keepers. At the December rally, an Oath Keepers leader told the assembled crowd, the President “needs to know from you that you are with him, [and] that if he does not do it while he is commander in chief, we’re going to have to do it ourselves later, in a much more desperate, much more bloody war.” Id. ¶ 54.

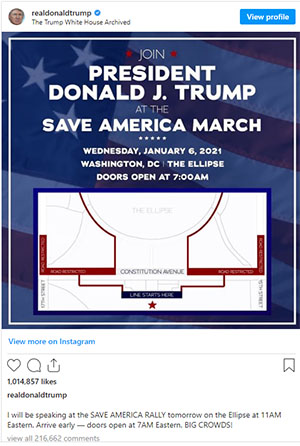

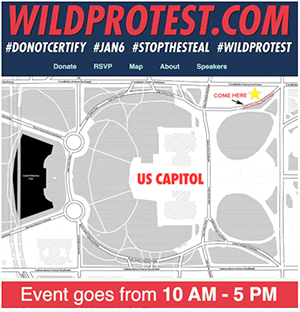

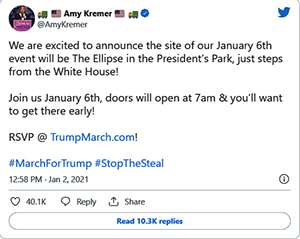

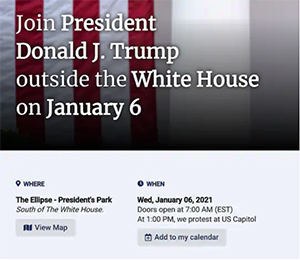

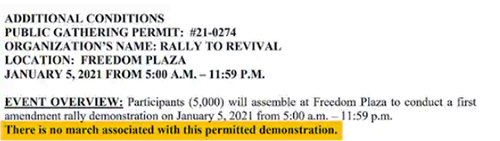

2. Preparations for the January 6 Rally

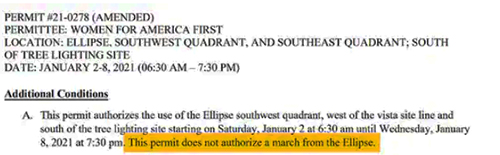

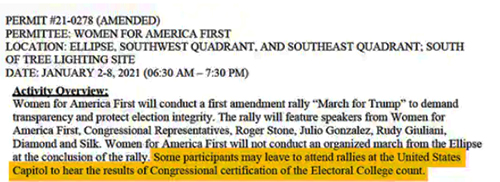

On December 19, 2020, President Trump announced that there would be a rally in Washington, D.C., on January 6th, the day of the Certification of the Electoral College: “Big protest in D.C. on January 6th. Be there, will be wild!” Swalwell Compl. ¶ 86. The President and his campaign were involved in planning and funding the rally. He participated in selecting the speaker lineup and music, and his campaign made direct payments of $3.5 million to rally organizers. Thompson Compl. ¶¶ 68–69. Significantly, the rally was not permitted for a march from the Ellipse. Id. ¶ 90. The President and his campaign came up with the idea for a march to the Capitol. Id. ¶ 69.

Pro-Trump message boards and social media lit up after the President’s tweet announcing the January 6 Rally. Some followers viewed the President’s tweet as “marching orders.” One user posted, referring to the President’s debate statement to the Proud Boys, “standing by no longer.” Swalwell Compl. ¶ 88; Thompson Compl. ¶ 57. Other supporters explicitly contemplated “[s]torm[ing] the [Capitol],” and some posted about “Operation Occupy the Capitol” or tweeted using the hashtag #OccupyCapitols. Swalwell Compl. ¶ 89; Thompson Compl. ¶ 62.

The President knew that his supporters had posted such messages. He and “his advisors actively monitored the websites where his followers made these posts.” Thompson Compl. ¶ 66. News outlets, including Fox News, discussed them, as well. Id. On December 28, 2020, in widely publicized remarks, a former White House aide predicted, “there will be violence on January 6th because the president himself encourages it.” Id.

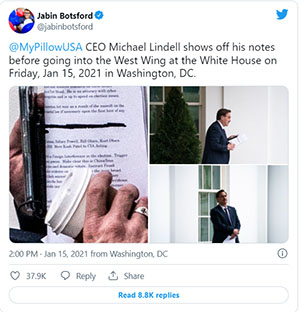

Trump’s allies also worked to promote the January 6 Rally. Trump Jr. posted a video on Instagram asking his followers to “Be Brave. Do Something.” Swalwell Compl. ¶ 74. Giuliani tweeted a video purporting to explain how Vice President Mike Pence could block the certification of the election results. Id. ¶ 65. Brooks posted on social media on the eve of the rally that the President “asked [him] personally to speak & tell the American people about the election system weaknesses that the Socialist Democrats exploited to steal this election.” Id. ¶ 84.

At the same time, members of the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers began their preparations for the rally in earnest. On December 19 and 25, 2020, leaders of the Oath Keepers announced that they had “organized an alliance” and “orchestrated a plan” with the Proud Boys. Thompson Compl. ¶ 63. Tarrio said that the Proud Boys would turn out in “record numbers.” Id. ¶ 64. The groups also secured tactical and communications equipment. Id. ¶ 65. The Oath Keepers recruited additional members and prepared them with military-style training. Id. ¶ 127.

3. January 6th—The Riot at the Capitol Building

The “Save America” rally on the Ellipse began at about 7:00 a.m. Blassingame Compl. ¶ 58. Brooks took the stage around 8:50 a.m. Swalwell Compl. ¶ 84. The Congressman said, among other things, that “[w]e are great because our ancestors sacrificed their blood, their sweat, their tears, their fortunes, and sometimes their lives,” and that “[t]oday is the day American patriots start taking down names and kicking ass!” Id. ¶¶ 106, 108. After Brooks finished, Giuliani spoke. He repeated that the “election was stolen” and said that it “has to be vindicated to save our country.” Id. ¶ 113. Then, in the context of discussing how disputes over election fraud might be resolved, he proclaimed, “Let’s have trial by combat!” Id. ¶ 114. Trump Jr. gave the last speech before the President took to the podium. He spent much of his remarks claiming that the Republican Party belongs to Donald Trump. He also warned Republican members of Congress, “If you’re gonna be the zero, and not the hero, we’re coming for you, and we’re gonna have a good time doing it.” Id. ¶¶ 117–119.

At about noon, President Trump took the stage. Id. ¶ 121. The court will discuss the President’s speech in much greater detail later in this opinion, so recites only portions here. The President spoke for 75 minutes, and during that time, he pressed the false narrative of a stolen election. He suggested that Vice President Pence could return Electoral College ballots to the states, allowing them to recertify Electors, which would bring about an election victory. He urged rally-goers to “fight like hell,” and he told them that “you’re allowed to go by very different rules” when fraud occurs. Swalwell Compl. ¶¶ 126, 128. Early in the speech he referenced a march to the Capitol and said he knew the crowd would be going there to “peacefully and patriotically” make their voices heard. An hour later, he punctuated his speech by saying that the election loss “can’t have happened and we fight, we fight like hell, and if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.” Thompson Compl. ¶ 88. He then directed his supporters to the Capitol. The crowd at various points responded, “Fight Like Hell. Fight for Trump,” and at other points, “Storm the Capitol,” “Invade the Capitol Building,” and “Take the Capitol right now.” Blassingame Compl. ¶ 61; Thompson Compl. ¶ 88.3 Responding to the President’s call, thousands marched to the Capitol building after he finished his remarks.

Meanwhile, Congress had convened a Joint Session at 1:00 p.m. to certify the Electoral College vote. Thompson Compl. ¶ 93. Outside the building, some supporters already had begun confrontations with Capitol Police. Even before the President’s speech had concluded, the Proud Boys, operating in small groups, had begun to breach the outer perimeter of the Capitol. Blassingame Compl. ¶ 66; Thompson Compl. ¶¶ 98–100. The Ellipse crowd began to arrive by 1:30 p.m. Blassingame Compl. ¶ 69. As their numbers grew, the crowd overwhelmed police and exterior barriers and entered the Capitol by 2:12 p.m. Swalwell Compl. ¶ 134. The Oath Keepers were among the crowd. Thompson Compl. ¶ 126. The Joint Session was suspended, and the Vice President and members of Congress were evacuated. Id. ¶ 111; Swalwell Compl. ¶¶ 135–136. Police officers, including the Blassingame Plaintiffs, were injured as violent confrontations continued with the President’s supporters.

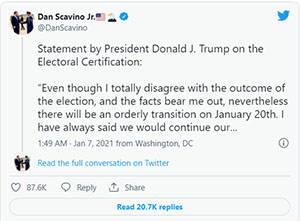

4. The President’s Response

After his speech, the President returned to the White House and watched the events at the Capitol unfold on television. Thompson Compl. ¶ 106. Despite pleas from advisors and Congressmen, the President did not immediately call on his supporters to leave the Capitol building. Blassingame Compl. ¶¶ 114, 116; Thompson Compl. ¶ 123. At about 2:24 p.m., after rioters had entered the Capitol, he sent a tweet critical of the Vice President for lacking “the courage to do what should have been done to protect our Country and our Constitution.” Blassingame Compl. ¶ 116. Eventually, two hours later, the President would tell his supporters to stand down. He tweeted a video calling on them to “[g]o home. We love you. You’re very special.” Id. ¶ 125.

The President sent one more tweet that day. After police had cleared the Capitol, around 6:00 p.m., the President said: “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide election victory is so unceremoniously & viciously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long. . . . Remember this day forever!” Id. ¶ 127.

The House of Representatives would later pass a single Article of Impeachment accusing President Trump of “Inciting an Insurrection,” but the Senate would acquit him after he left office.

B. Procedural History

1. Thompson v. Trump

The Thompson case was the first to come before the court on February 16, 2021. See Compl., ECF No. 1. The plaintiffs in that case are ten members of the House of Representatives.4 Although the case is captioned Thompson v. Trump, the court will refer to these plaintiffs as the “Bass Plaintiffs”—after the second named plaintiff, Representative Karen R. Bass—because the lead plaintiff, Representative Bennie G. Thompson, voluntarily dismissed his claims after his appointment to serve as the chair of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol. See Notice of Voluntary Dismissal, ECF No. 39. Although all are elected officials, the Bass Plaintiffs have filed suit in their personal capacities. See Thompson Compl.

The Bass Plaintiffs have named six defendants: President Trump, Giuliani, the Oath Keepers, Proud Boys International, Warboys LLC, and Tarrio. Id. They assert a single claim against all Defendants: a violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1985(1). Id. at 60. All Defendants except the Proud Boys and Warboys have appeared and moved to dismiss the claim against them. See Def. Oath Keepers’ Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 20 [hereinafter Thompson Oath Keepers’ Mot.]; Def. Giuliani’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 21, Mem. of P. & A. in Supp. of Def.’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 21-1 [hereinafter Thompson Giuliani Mot.]; Def. Trump’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 22, Mem. in Supp. of Def. Trump’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 22-1 [hereinafter Thompson Trump Mot.]; Def. Tarrio’s Notice of Intention to Join Mots. to Dismiss, ECF No. 64.

2. Swalwell v. Trump

Representative Eric Swalwell filed his action on March 5, 2021, also in his personal capacity. Swalwell Compl. He named as defendants President Trump, Trump Jr., Brooks, and Giuliani. His Complaint advances a host of federal and District of Columbia–law claims against all Defendants: (1) violation of § 1985(1) (Count 1); (2) violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1986 (Count 2); (3) two counts of negligence per se predicated on violations of District of Columbia anti-rioting and disorderly conduct criminal statutes (Counts 3 and 4); (4) violation of the District of Columbia anti-bias statute, D.C. Code § 22-3701 et seq. (Count 5); (5) intentional infliction of emotional distress (Count 6); (6) negligent infliction of emotional distress (Count 7); (7) aiding and abetting common law assault (Count 8); and (8) negligence (Count 9). Id. at 45–62.

Each Defendant except Brooks has moved to dismiss all claims against him. See Def. Giuliani’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 13, Mem. of P. & A. in Supp. of Def.’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 13-1 [hereinafter Swalwell Giuliani Mot.]; Defs. Trump & Trump Jr.’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 14, Mem. in Supp. of Trump & Trump Jr.’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 14-1 [hereinafter Swalwell Trump Mot.].

Brooks has moved for a scope-of-office certification under the Westfall Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2679. See Pet. to Certify Def. Mo Brooks Was Acting Within Scope of His Office or Employment, ECF No. 20. Under the Westfall Act, if the Attorney General certifies that a tort claim against an employee of government—including a member of Congress—arises from conduct performed while “acting within the scope of his office or employment,” the United States is to be substituted as the defendant. 28 U.S.C. § 2679(d)(1). Brooks asked the Attorney General for a Westfall Act certification, but he declined the request. See U.S. Resp. to Def. Mo Brooks’s Petition to Certify He Was Acting Within Scope of His Office or Employment, ECF No. 33 [hereinafter U.S. Resp. to Brooks]. Notwithstanding the Attorney General’s denial, the Westfall Act authorizes a court to make the requisite certification. See 28 U.S.C. § 2679(d)(3) (“In the event that the Attorney General has refused to certify scope of office or employment under this section, the employee may at any time before trial petition the court to find and certify that the employee was acting within the scope of his office or employment.”). Brooks seeks such relief from the court.

3. Blassingame v. Trump

The third action is brought by James Blassingame and Sidney Hemby, two Capitol Police officers who were on duty and injured on January 6th. They name only President Trump as a defendant. Blassingame Compl. They advance numerous federal and District of Columbia–law claims: (1) directing assault and battery (Count 1); (2) aiding and abetting assault and battery (Count 2); (3) directing intentional infliction of emotional distress (Count 3); (4) two counts of negligence per se predicated on violations of District of Columbia anti-rioting and disorderly conduct criminal statutes (Counts 4 and 5); (5) punitive damages (Count 6); (6) violation of § 1985(1) (Count 7); and (7) civil conspiracy in violation of common law (Count 8). See id. at 36–48.

Defendant Trump has moved to dismiss all counts against him. Def. Trump’s Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 10, Def.’s Mem. in Supp. of His Mot. to Dismiss, ECF No. 10-1 [hereinafter Blassingame Trump Mot.].

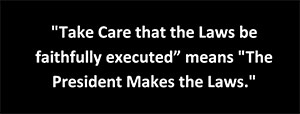

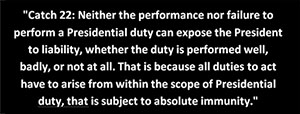

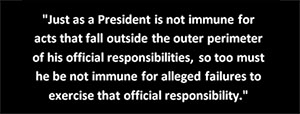

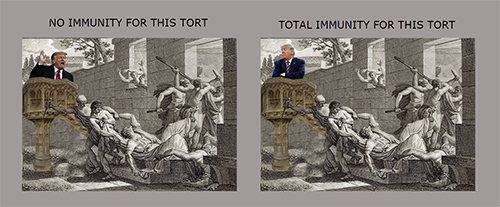

4. The Motions to Dismiss

Defendants’ arguments for dismissal are the same across all three cases. Generally, all Defendants contend the following: (1) Plaintiffs lack standing to sue under Article III of the Constitution; (2) the First Amendment bars Plaintiffs’ claims; and (3) Plaintiffs have failed to state claims under § 1985(1) and District of Columbia law. President Trump advances a number of contentions that are specific to him: (1) he is absolutely immune from suit; (2) the political question doctrine renders these cases nonjusticiable; (3) the Impeachment Judgment Clause bars civil suits against a government official, like him, acquitted following impeachment; and (4) the doctrines of res judicata and collateral estoppel premised on his acquittal by the Senate preclude all of Plaintiffs’ claims.

The court held oral argument on January 10, 2022, on Defendants’ motions. See Hr’g Tr., ECF No. 63.