Presidents, Patriots, and the First Amendment: Can President Trump Legally Praise Putin?

By Chat GPT

5/12/25

Q. Does Pres. Trump have the legal right to express support for Russia as to the Russia-Ukrainian war when a lot of people think that stand is against American foreign policy interests? And isn't the president the ultimate determiner of what is in our best foreign interests? Does this come under the President's 1st amendment rights, just as it does with the rest of us, or is he a special exception who does not have that 1st amendment right to speech like the rest of us?

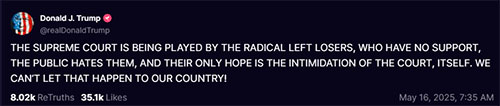

A. President Donald Trump’s favorable remarks about Vladimir Putin and criticism of U.S. support for Ukraine have ignited a firestorm. His opponents call it unpatriotic or even treasonous. But in a country founded on free speech and governed by the Constitution, the issue is not how the comments are perceived—but whether they are lawful.

The answer is yes. President Trump’s statements are constitutionally protected, and indeed, as the current head of state, he possesses wide discretion to set and express foreign policy—even when it runs counter to tradition or popular opinion.

The First Amendment Applies to Presidents, Too

The First Amendment protects the right to freedom of speech for everyone—including the President of the United States. There is no exception carved out for speech that diverges from conventional foreign policy positions or criticizes longstanding alliances.

Presidents have historically used their office to challenge prior policies. Think of Woodrow Wilson’s neutrality, FDR’s early reluctance to confront Nazi Germany, or Richard Nixon’s overtures to Communist China. These weren’t illegal—they were constitutional exercises of executive leadership.

Even if the public or Congress disagrees, the President retains the right to voice and implement his views, unless constrained by statute or treaty.

The President Shapes Foreign Policy

Under Article II of the Constitution, the President is the Commander in Chief of the armed forces and the chief architect of foreign policy. This authority was emphasized by the Supreme Court in United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. (1936), which described the President as the “sole organ” of the federal government in international relations.

So, when President Trump expresses skepticism about NATO or support for negotiations with Russia, he isn’t merely offering an opinion—he’s performing his constitutional role.

Whether his views are controversial or unconventional is politically relevant—but not legally disqualifying.

Treason? Not Even Close

Some critics reach for the most inflammatory accusation: treason. But treason is narrowly defined in the Constitution (Art. III, §3) as levying war against the U.S. or “adhering to [its] enemies, giving them aid and comfort.” Expressing admiration for a foreign leader, proposing peace talks, or questioning military aid does not meet that bar—not even remotely.

No court has ever held that a President’s statements, by themselves, constitute treason—no matter how unorthodox or unpatriotic they might sound.

Dangerous Speech? That’s a Political Judgment

Under Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), speech cannot be punished unless it is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and likely to do so. President Trump’s foreign policy views, no matter how divisive, fall far outside that exception.

The appropriate check on presidential speech is not prosecution—it is political accountability: elections, congressional oversight, and the public square.

Dissent in the Oval Office Is Not New

History is replete with examples of presidents who challenged the foreign policy consensus:

• FDR defied isolationists to support Britain before WWII.

• Reagan negotiated with the “evil empire” despite years of Cold War hostility.

• Obama negotiated a nuclear deal with Iran amid fierce bipartisan criticism.

President Trump’s views on Russia may provoke outrage, but he follows in a long tradition of American leaders willing to break foreign policy molds.

Conclusion: A Constitutional Right and Presidential Power

President Trump is not only allowed to express controversial views about Russia—he is constitutionally empowered to reshape U.S. foreign policy based on those views. That power is not unchecked, but it is real. If the public or Congress disagrees, they have political tools—not legal ones.

Calling such speech “treason” or “illegal” is not just inaccurate—it risks undermining the very freedoms we claim to defend.

In America, we don’t jail presidents for their opinions. We debate them, we oppose them, or we vote them out. That’s how constitutional government works—even in times of global conflict and political strife.

********************************

Part 2

Q. Do a lot of Americans think that Russia is a Communist country, and Putin is a communist dictator? And is Russia an automatic symbol of communism to a lot of Americans?

ChatGPT said:

Yes, many Americans—especially older generations or those less familiar with post-Soviet geopolitics—still conflate modern Russia with Soviet-style communism, and often view Vladimir Putin as a "communist dictator" despite the current reality being quite different. This stems from a combination of historical memory, political rhetoric, and oversimplified media portrayals. Let’s break it down:

1. Historical Legacy: Cold War Conditioning

• For decades during the Cold War, the Soviet Union was the primary adversary of the United States and the leader of the global communist bloc.

• Russia, as the largest Soviet republic, was often seen as synonymous with communism.

• American culture, media, and education during the 20th century instilled a deep-seated association: Russia = Communism = Enemy.

• For Baby Boomers and Gen X, that association remains psychologically sticky, even though the USSR dissolved in 1991.

2. Is Russia Communist Today? No.

• Modern Russia is not a communist country. It is a federal semi-presidential republic with a capitalist economy dominated by oligarchic state-private alliances.

• The Communist Party of the Russian Federation exists, but it is an opposition party and does not govern.

• The ruling party is United Russia, which espouses nationalism, authoritarianism, and “managed democracy”—not communism.

3. Is Putin a Communist Dictator?

• No, not in the classical sense. Vladimir Putin is an authoritarian strongman, but his ideology is not Marxist-Leninist.

• Putin promotes Orthodox Christian nationalism, imperial nostalgia, and anti-Western sentiment, but not state socialism or classless communism.

• He has also made explicit efforts to rehabilitate the image of the Russian Empire and the Orthodox Church, not the Communist Party.

4. Why Do Some Americans Still Use “Communist” as a Label?

• In U.S. political discourse, especially in populist or right-wing rhetoric, “communist” is often used as a general insult for any authoritarian or anti-American regime.

• Some Americans may label Putin a communist out of habit, confusion, or as shorthand for “bad foreign leader aligned against the U.S.”

• Media simplifications, limited foreign affairs education, and ideological tribalism all reinforce this conflation.

5. So Is Russia Still a “Symbol of Communism”?

• To some Americans, yes—particularly older generations, Cold War veterans, or those who don’t distinguish between Soviet history and modern geopolitics.

• To more informed or younger Americans, Russia is more accurately seen as an autocratic, nationalist, corrupt capitalist state—not a communist one.

Conclusion

While Russia today is not communist, many Americans still reflexively associate it with communism, and some wrongly describe Putin as a communist dictator. This is more about historical memory and rhetorical shorthand than political reality.

***************

Part 3

And when did Ukraine become a "democratic" state, and under which American-led circumstances did it become so?

ChatGPT said:

Ukraine’s evolution into a democratic state has been messy, contested, and incomplete, but it has generally moved toward democracy since gaining independence in 1991. However, its progress has been heavily influenced by American and European support, especially after two major popular uprisings—the Orange Revolution (2004) and the Euromaidan Revolution (2013–2014).

Here's a structured overview of when and how Ukraine became a “democratic” state, and how the U.S. helped shape that process:

Ukraine’s Path Toward Democracy

• 1991: Independence from the Soviet Union

Ukraine declared independence on August 24, 1991, and confirmed it by popular referendum in December 1991.

The first president, Leonid Kravchuk, was a former Communist official, and the early 1990s were marked by oligarchic capitalism, corruption, and weak institutions.

While technically a republic with elections, democracy was largely nominal in the 1990s.

• 2004: The Orange Revolution

Presidential elections in 2004 were widely seen as rigged in favor of pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych.

Massive protests erupted in Kyiv, culminating in the Orange Revolution.

The U.S. supported civil society groups, election monitors, and independent media via USAID, NED (National Endowment for Democracy), and other channels.

A re-run of the election led to a victory for pro-Western candidate Viktor Yushchenko.

U.S. Role: While not a direct “regime change,” American NGOs and State Department programs helped fund democratic activism. Russia denounced it as a CIA-backed color revolution.

• 2010–2014: Authoritarian Backslide and Euromaidan

Yanukovych returned to power in 2010 and began consolidating authoritarian control.

In 2013, he rejected an EU Association Agreement, triggering mass protests—known as the Euromaidan Revolution or Revolution of Dignity.

Violent crackdowns in early 2014 led to Yanukovych fleeing the country.

• U.S. Role: The U.S. openly supported Euromaidan activists, with Senator John McCain and Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland visiting the square. Leaked calls revealed U.S. interest in shaping post-Yanukovych leadership.

• 2014–Present: Post-Revolution Reform and War

After 2014, Ukraine undertook democratic reforms, strengthened its parliament, and cracked down on corruption (with limited success).

Russia responded by annexing Crimea and backing separatists in eastern Ukraine.

In 2019, comedian-turned-reformer Volodymyr Zelenskyy was elected president with a strong anti-corruption and pro-Western mandate.

• U.S. Role: After 2014, the U.S. significantly increased support for Ukrainian democracy, defense, anti-corruption efforts, and integration with NATO and the EU. This support further deepened the West/Russia divide.

So When Did Ukraine Become “Democratic”?

There is no single date when Ukraine became a true democracy, but the post-2014 period, especially after the Euromaidan uprising, is when democratic institutions began to solidify—under direct Western encouragement and with U.S. strategic backing.

It is still a hybrid system, with corruption, oligarchic influence, and wartime martial laws complicating the picture. But it holds competitive elections, has relatively free media (compared to Russia), and a vibrant civil society.

Summary of American-Led Circumstances

Year / Event / U.S. Involvement

1991 Independence Recognized Ukraine; began aid programs

2004 Orange Revolution Funded NGOs, election monitoring; supported pro-democracy protests

2013–14 Euromaidan Supported civil society; criticized Yanukovych; encouraged EU alignment

2014–2022 Post-Maidan Funded reforms, training, military assistance; aligned with NATO strategy

2022–Now Russian invasion Massive U.S. military, economic, and democratic support

*******************

Part 4

Q. What is the role and history of Victoria Nuland in Ukraine's "democracy building" exercise?

ChatGPT said:

Victoria Nuland has played a central and highly visible role in the U.S. government's efforts to influence Ukraine’s political trajectory, particularly during key democratic upheavals. A career diplomat and foreign policy heavyweight, Nuland has served as a senior architect of U.S. policy toward Ukraine across both Republican and Democratic administrations.

Her involvement spans nearly two decades, peaking during the 2013–2014 Euromaidan Revolution, when she became both a symbol of U.S. support for democracy and, in the eyes of critics, a lightning rod for accusations of American regime meddling.

Who Is Victoria Nuland?

Career: U.S. diplomat with posts under Cheney, Clinton, Obama, and Biden.

Key Roles:

• U.S. Ambassador to NATO (2005–2008)

• State Dept. Spokesperson under Secretary Hillary Clinton (2011–2013)

• Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs (2013–2017)

• Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs (2021–2024) under President Biden

She is married to neoconservative writer Robert Kagan, co-founder of the Project for the New American Century (PNAC).

Victoria Nuland’s Role in Ukraine

1. Pre-Euromaidan Diplomacy (2013)

• As Assistant Secretary of State, Nuland pressed the Yanukovych government to sign an EU Association Agreement.

• When President Yanukovych rejected it in favor of closer Russian ties, mass protests erupted in Kyiv—the start of the Euromaidan movement.

2. “Cookies on the Maidan” (December 2013)

• Nuland visited protesters in Independence Square (Maidan) and handed out food, symbolizing U.S. solidarity with anti-Yanukovych demonstrators.

• This was widely broadcast and criticized by Russia as direct interference in Ukraine’s internal affairs.

3. The Leaked Call ("F* the EU") — February 2014**

• A phone call between Nuland and U.S. Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt was leaked online.

• They discussed preferred opposition leaders and how to “glue this thing together.”

• Nuland said “F* the EU**,” reflecting frustration with EU diplomacy.

• Russia used the leak as proof of U.S. orchestration of regime change.

Key Quote:

“Yats is the guy... He’s got the economic experience, the governing experience.”

(referring to Arseniy Yatsenyuk, who soon became prime minister)

4. Post-Revolution Period (2014–2016)

• Nuland remained deeply involved in shaping U.S. support for Ukraine’s transitional government.

• Promoted anti-corruption measures, constitutional reforms, and NATO integration.

• Worked on U.S. military and financial assistance packages.

• Helped isolate Russia diplomatically and build support for sanctions after Crimea’s annexation.

5. Under Biden (2021–2024)

• Returned as Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs.

• Advocated continued military and economic support to Ukraine after Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

• Championed the narrative that Ukraine’s democratic resilience is critical to U.S. national interest.

Controversy & Criticism

Russia’s View: “Regime Change Architect”

• Nuland is a frequent target of Russian propaganda, portrayed as a “color revolution” puppet master.

• The 2014 leak and public support for regime change are cited as proof of U.S. interference.

Criticism from Non-Interventionists

• Critics, including some on the American right and left, argue that Nuland helped provoke Russia into aggression by pushing NATO alignment and regime change.

Summary of Nuland’s Impact

Period / Action / Effect

2013 Advocated EU alignment Sparked tension with Yanukovych

2013–14 Supported Maidan protesters Emboldened revolutionaries, angered Russia

Feb 2014 Leaked call Damaged EU-U.S. unity, exposed backchannel strategy

2014–16 Supported reform agenda Boosted U.S. influence in post-Yanukovych Ukraine

2021–24 Led State Dept. policy under Biden Central figure in post-2022 support for Ukraine

Final Thought

Victoria Nuland's role in Ukraine is emblematic of modern U.S. democracy promotion: a mix of diplomacy, realpolitik, soft power, and strategic containment of adversaries like Russia. Whether seen as a champion of democratic values or an agent of foreign interference, she has undeniably been one of the most influential American officials in shaping Ukraine’s current political direction.

Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Gates

Re: Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Ga

Trump Thinks He Can Get Around Due Process by Suspending Habeas Corpus? Federal Judges Disagree!

by Glenn Kirschner

May 12, 2025

Donald Trump apparently thinks the Constitution is inconvenient, getting in the way of his fervent desire to deport anyone and everyone he wants out of the United States.

His latest unconstitutional scheme is to suspend the writ of Habeas Corpus, which enables people being confined by Trump's executive branch to challenge the legality of their detention.

Trump and his henchmen, guys like Stephen Miller, apparently think they can unilaterally suspend habeas corpus? The problem for them is the federal courts disagree, including Republican/conservative icon, the late Justice Antonin Scalia.

Transcript

so friends donald trump and his little

minions like steven miller and others

find the constitution really

inconvenient because it's stopping them

from doing what they want to do

fortunately federal judges continue to

insist that trump's executive branch

abide by the

constitution let's talk about that

because justice

[Music]

matters hey all glen kersner here so

friends donald trump really wants to

deport folks doesn't he i mean starting

with immigrants but does anybody doubt

that he'll make his way to imprisoning

and deporting his political opponents

and heck anybody who displeases him but

there's a problem for donald trump a

real challenge it is that pesky

constitutional right of due process

notice and opportunity to be heard by a

judge because it's not donald trump who

makes the ultimate decision whether

somebody can be properly detained and

deported no it's a

judge and trump and steven miller and

those of their ilk don't like that one

little bit so they're cooking up a new

scheme and federal judges are sounding

alarm bells

let's start with some new reporting in

politico headline judges warn trump's

mass deportations could lay groundwork

to ensnare americans and that article

begins a fundamental promise by

americans founders that no one should be

punished by the state by the government

without a fair hearing is under threat a

growing chorus of federal judges say and

here's what some of those federal judges

are saying quote "when the courts say

due process is important we're not

unhinged we're not radicals." us

district judge anna reyes a washington

dcbased appointee of president joe biden

said at a recent hearing quote "we are

literally trying to enforce a process

embodied in probably the most

significant document with respect to

people's rights against tyrannical

government oppression." that's what

we're doing here okay and friends it's

not just judges who were appointed by

presidents who happen to be democrats

that are sounding the alarm about what

trump and company are trying to do

there's this from a judge appointed by

president ronald reagan

quote "if today the executive claims the

right to deport without due process,"

and this was judge wilkinson speaking

about immigrants in the context of the

abrego garcia case if the executive the

president claims the right to deport

without due process and in disregard of

court orders what assurance will there

be tomorrow that it will not deport

american citizens and then disclaim

responsibility to bring them home

wondered j harvey wilkinson a ronald

reagan appointee to the richmondbased

fourth circuit court of appeals judge

wilkinson described an incipient crisis

but also an opportunity to rally around

the rule of law and in the abrego garcia

opinion judge wilkinson went on to say

this and what asurances shall there be

that the executive the president will

not train its broad discretionary powers

upon its political enemies

the threat even if not the actuality

would always be president and the

executive's obligation to take care that

the laws be faithfully executed would

lose its meaning and friends can i

reference just one more judge or

actually in this case a supreme court

justice who believes that the

constitutional due process right of

notice and opportunity to be heard by a

judge are pretty damn important

it's a fight the judges are increasingly

casting as existential rooted in the

fifth amendment's guarantee that no

person shall be deprived of life liberty

or property without due process of law

the word person courts have noted makes

no distinction between citizens or

non-citizens

the supreme court has long held that

this fundamental promise extends to

immigrants in deportation proceedings in

a 1993 opinion justice antinine scalia

called that principle well

established that's right friends supreme

court justice antinine scalia it doesn't

get any more conservative in recent

generations on the supreme court than

justice scalia and he said "it is well

established that citizens and

noncitizens enjoy due process rights."

but donald trump and steven miller don't

like that they don't like the kind of

things that reagan appointed judge

harvey wilkinson say about how everyone

every person enjoys due process rights

notice and opportunity to be heard by a

judge they don't like courts having

their say they don't like the

constitution having its say donald trump

doesn't seem to be fond of the whole

checks and balances that are necessary

to the lawful operation of our

government so they are hatching a new

unconstitutional

scheme just get rid of due process

altogether

extinguish the right of the people to

notice an opportunity to be heard by

suspending the process that protects

that right the writ of habius corpus

what we refer to as the great writ it is

the writ it is the vehicle the mechanism

the procedure that protects people

citizens and non-citizens alike from

being unlawfully

imprisoned

unconstitutionally detained by the

executive branch by the trump

administration

and here's some of the reporting

regarding this new

unconstitutional scheme miller trump and

others are cooking

up trump administration's threat to

suspend core us legal right sparks

outcry and

alarm and that article begins "legal

experts and democrats expressed growing

alarm over the weekend that trump

administration officials are openly

discussing unilaterally suspending

habius corpus a bedrock american legal

right without the approval of congress

the rid of habius corpus which dates

back centuries grants anyone detained in

the us the right to see a judge

challenged the government's evidence

against them and present a defense but

white house deputy chief of staff steven

miller downplayed its significance on

friday suggesting that the

administration could move to suspend it

unilaterally

quote "that's an option we're actively

looking at," miller told reporters at

the white house steven vladic a

constitutional law professor at

georgetown university described miller's

statement on substack as factually and

legally nuts and called it the most

remarkable and remarkably scary comments

about federal courts that i think we've

ever heard from a senior white house

official

other legal scholars strongly challenged

miller's assertion that the president

could unilaterally suspend habius corpus

latin for that you have the body and let

me just add here essentially the writ of

habius corpus is a writ that can be

ordered issued by a judge directing the

government the executive branch to bring

me the body of the person you are

detaining

vladic and three other experts said that

a legal consensus has existed for

decades that only congress has the

authority to suspend the right the rid

of habius corpus they noted that article

one of the constitution which describes

congress's powers states the privilege

of the writ of habius corpus shall not

be suspended unless when in cases of

rebellion or invasion the public safety

may require it ilia sman a law professor

at george mason university called

miller's claim that the president has

the power to unilaterally suspend habius

corpus false quote "habius corpus can

only be suspended under the constitution

in times of invasion or insurrection

none of that is happening now said sman

a libertarian legal scholar and the

simon chair of constitutional studies at

the libertarian kato institute quote and

it can only be done by congress not the

president acting on his own

sman and jonathan adler a law professor

at case western reserve university cited

a 2004 supreme court ruling in which

conservative justice sandre de o' conor

concluded that only congress has the

authority to suspend habius corpus

justice okconor also emphasized that

habius corpus has acted as a critical

check on the executive branch's power in

other words a critical check on donald

trump's power to unlawfully detain

individuals in the us and one more time

let's go to the guru of all things

conservative on the supreme court

justice

scalia supreme court justice antinine

scalia a conservative icon agreed in an

opinion of his own that the power to

suspend habius corpus rests solely with

congress he also said that the executive

branch the trump administration cannot

unilaterally round up americans and hold

them in detention without charge even in

times of rebellion

you know friends these conservative

icons who are revered in republican

circles justice scalia justice okconor

judge wilkinson all prove to any

thinking person's

satisfaction that donald trump and

steven miller are

unconstitutional

hacks i would go so far as to call them

constitutional cannibals

and yet what do we hear from the

republicans in

congress

crickets i mean are they really going to

let donald trump destroy our

constitution terminate our

constitutional construct of government

or at some point will they cross the

aisle to save democracy

you know to our republican friends i

would say in a world of donald trump's

and stephen

miller's be a liz

cheney be an adam

kinzinger just cross the aisle to save

democracy because

justice

matters friends as always please stay

safe please stay tuned and i look

forward to talking with you all again

tomorrow

[Music]

by Glenn Kirschner

May 12, 2025

Donald Trump apparently thinks the Constitution is inconvenient, getting in the way of his fervent desire to deport anyone and everyone he wants out of the United States.

His latest unconstitutional scheme is to suspend the writ of Habeas Corpus, which enables people being confined by Trump's executive branch to challenge the legality of their detention.

Trump and his henchmen, guys like Stephen Miller, apparently think they can unilaterally suspend habeas corpus? The problem for them is the federal courts disagree, including Republican/conservative icon, the late Justice Antonin Scalia.

Transcript

so friends donald trump and his little

minions like steven miller and others

find the constitution really

inconvenient because it's stopping them

from doing what they want to do

fortunately federal judges continue to

insist that trump's executive branch

abide by the

constitution let's talk about that

because justice

[Music]

matters hey all glen kersner here so

friends donald trump really wants to

deport folks doesn't he i mean starting

with immigrants but does anybody doubt

that he'll make his way to imprisoning

and deporting his political opponents

and heck anybody who displeases him but

there's a problem for donald trump a

real challenge it is that pesky

constitutional right of due process

notice and opportunity to be heard by a

judge because it's not donald trump who

makes the ultimate decision whether

somebody can be properly detained and

deported no it's a

judge and trump and steven miller and

those of their ilk don't like that one

little bit so they're cooking up a new

scheme and federal judges are sounding

alarm bells

let's start with some new reporting in

politico headline judges warn trump's

mass deportations could lay groundwork

to ensnare americans and that article

begins a fundamental promise by

americans founders that no one should be

punished by the state by the government

without a fair hearing is under threat a

growing chorus of federal judges say and

here's what some of those federal judges

are saying quote "when the courts say

due process is important we're not

unhinged we're not radicals." us

district judge anna reyes a washington

dcbased appointee of president joe biden

said at a recent hearing quote "we are

literally trying to enforce a process

embodied in probably the most

significant document with respect to

people's rights against tyrannical

government oppression." that's what

we're doing here okay and friends it's

not just judges who were appointed by

presidents who happen to be democrats

that are sounding the alarm about what

trump and company are trying to do

there's this from a judge appointed by

president ronald reagan

quote "if today the executive claims the

right to deport without due process,"

and this was judge wilkinson speaking

about immigrants in the context of the

abrego garcia case if the executive the

president claims the right to deport

without due process and in disregard of

court orders what assurance will there

be tomorrow that it will not deport

american citizens and then disclaim

responsibility to bring them home

wondered j harvey wilkinson a ronald

reagan appointee to the richmondbased

fourth circuit court of appeals judge

wilkinson described an incipient crisis

but also an opportunity to rally around

the rule of law and in the abrego garcia

opinion judge wilkinson went on to say

this and what asurances shall there be

that the executive the president will

not train its broad discretionary powers

upon its political enemies

the threat even if not the actuality

would always be president and the

executive's obligation to take care that

the laws be faithfully executed would

lose its meaning and friends can i

reference just one more judge or

actually in this case a supreme court

justice who believes that the

constitutional due process right of

notice and opportunity to be heard by a

judge are pretty damn important

it's a fight the judges are increasingly

casting as existential rooted in the

fifth amendment's guarantee that no

person shall be deprived of life liberty

or property without due process of law

the word person courts have noted makes

no distinction between citizens or

non-citizens

the supreme court has long held that

this fundamental promise extends to

immigrants in deportation proceedings in

a 1993 opinion justice antinine scalia

called that principle well

established that's right friends supreme

court justice antinine scalia it doesn't

get any more conservative in recent

generations on the supreme court than

justice scalia and he said "it is well

established that citizens and

noncitizens enjoy due process rights."

but donald trump and steven miller don't

like that they don't like the kind of

things that reagan appointed judge

harvey wilkinson say about how everyone

every person enjoys due process rights

notice and opportunity to be heard by a

judge they don't like courts having

their say they don't like the

constitution having its say donald trump

doesn't seem to be fond of the whole

checks and balances that are necessary

to the lawful operation of our

government so they are hatching a new

unconstitutional

scheme just get rid of due process

altogether

extinguish the right of the people to

notice an opportunity to be heard by

suspending the process that protects

that right the writ of habius corpus

what we refer to as the great writ it is

the writ it is the vehicle the mechanism

the procedure that protects people

citizens and non-citizens alike from

being unlawfully

imprisoned

unconstitutionally detained by the

executive branch by the trump

administration

and here's some of the reporting

regarding this new

unconstitutional scheme miller trump and

others are cooking

up trump administration's threat to

suspend core us legal right sparks

outcry and

alarm and that article begins "legal

experts and democrats expressed growing

alarm over the weekend that trump

administration officials are openly

discussing unilaterally suspending

habius corpus a bedrock american legal

right without the approval of congress

the rid of habius corpus which dates

back centuries grants anyone detained in

the us the right to see a judge

challenged the government's evidence

against them and present a defense but

white house deputy chief of staff steven

miller downplayed its significance on

friday suggesting that the

administration could move to suspend it

unilaterally

quote "that's an option we're actively

looking at," miller told reporters at

the white house steven vladic a

constitutional law professor at

georgetown university described miller's

statement on substack as factually and

legally nuts and called it the most

remarkable and remarkably scary comments

about federal courts that i think we've

ever heard from a senior white house

official

other legal scholars strongly challenged

miller's assertion that the president

could unilaterally suspend habius corpus

latin for that you have the body and let

me just add here essentially the writ of

habius corpus is a writ that can be

ordered issued by a judge directing the

government the executive branch to bring

me the body of the person you are

detaining

vladic and three other experts said that

a legal consensus has existed for

decades that only congress has the

authority to suspend the right the rid

of habius corpus they noted that article

one of the constitution which describes

congress's powers states the privilege

of the writ of habius corpus shall not

be suspended unless when in cases of

rebellion or invasion the public safety

may require it ilia sman a law professor

at george mason university called

miller's claim that the president has

the power to unilaterally suspend habius

corpus false quote "habius corpus can

only be suspended under the constitution

in times of invasion or insurrection

none of that is happening now said sman

a libertarian legal scholar and the

simon chair of constitutional studies at

the libertarian kato institute quote and

it can only be done by congress not the

president acting on his own

sman and jonathan adler a law professor

at case western reserve university cited

a 2004 supreme court ruling in which

conservative justice sandre de o' conor

concluded that only congress has the

authority to suspend habius corpus

justice okconor also emphasized that

habius corpus has acted as a critical

check on the executive branch's power in

other words a critical check on donald

trump's power to unlawfully detain

individuals in the us and one more time

let's go to the guru of all things

conservative on the supreme court

justice

scalia supreme court justice antinine

scalia a conservative icon agreed in an

opinion of his own that the power to

suspend habius corpus rests solely with

congress he also said that the executive

branch the trump administration cannot

unilaterally round up americans and hold

them in detention without charge even in

times of rebellion

you know friends these conservative

icons who are revered in republican

circles justice scalia justice okconor

judge wilkinson all prove to any

thinking person's

satisfaction that donald trump and

steven miller are

unconstitutional

hacks i would go so far as to call them

constitutional cannibals

and yet what do we hear from the

republicans in

congress

crickets i mean are they really going to

let donald trump destroy our

constitution terminate our

constitutional construct of government

or at some point will they cross the

aisle to save democracy

you know to our republican friends i

would say in a world of donald trump's

and stephen

miller's be a liz

cheney be an adam

kinzinger just cross the aisle to save

democracy because

justice

matters friends as always please stay

safe please stay tuned and i look

forward to talking with you all again

tomorrow

[Music]

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40037

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Ga

Donald Trump speaks at Saudi-US investment forum in Riyadh – watch live

Guardian News

The US president, Donald Trump, speaks at the Saudi-US investment forum in Riyadh, which is being attended by some of America's top bankers, tech executives, Saudi officials and business leaders

Guardian News

The US president, Donald Trump, speaks at the Saudi-US investment forum in Riyadh, which is being attended by some of America's top bankers, tech executives, Saudi officials and business leaders

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40037

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Ga

Georgetown scholar Badar Khan Suri released after ICE detention in Texas

by Gloria Pazmino and Emily R. Condon

CNN

5/15/25

https://www.cnn.com/2025/05/14/us/judge ... -khan-suri

Georgetown University post-doctoral fellow Badar Khan Suri has been ordered released by a US district judge in Virginia. Georgetown University

Georgetown University scholar Badar Khan Suri was released from a federal detention center in Texas on Wednesday, marking at least the third time a detained student or academic targeted by the Trump administration because of their protest activity or affiliation was released from immigration detention.

Earlier on Wednesday, US District Court Judge Patricia Tolliver Giles, issuing her ruling from the bench, said the government had failed to provide any evidence to continue to detain Khan Suri, who has been held in a Texas immigration detention facility for two months.

“I gave the government multiple opportunities to submit any type of filing to controvert these claims or support their opposition to these motions and they declined,” Tolliver Giles said.

The judge ordered Khan Suri’s release without bond, only requiring him to continue living in Virginia and to attend court proceedings in person. Khan Suri will be able to attend his deportation proceedings virtually, which are unfolding in Texas, Tolliver Giles said.

Badar Khan Suri (left) is photographed leaving US Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Prairieland Detention Facility in Alvarado, Texas on Wednesday. Phuong Tran/ACLU

Khan Suri is one of several non-citizen international scholars, faculty and students who have been detained or targeted for immigration enforcement as part of the Trump administration’s effort to target noncitizens who have participated in pro-Palestinian activism. Others include Mahmoud Khalil, Rümeysa Öztürk, Mohsen Madawi and Momodou Taal.

Last month, a Vermont judge ordered Columbia University student and permanent US resident Mohsen Mahdawi to be released. Mahdawi helped organize pro-Palestinian protests at Columbia and was detained during a citizenship appointment.

In Vermont last week, a judge ordered the release of Rümeysa Öztürk, a Turkish national and Tufts University student who was detained a year after she co-authored an op-ed in the school newspaper which was critical of the school’s response to the war in Gaza.

The cases have raised thorny legal questions about jurisdiction as well as First Amendment rights to free speech, which extend to both citizens and noncitizens under the US Constitution.

“He should have never been arrested and jailed for his constitutionally protected speech, just because our government disagrees with him,” said Sophia Gregg, an attorney for the ACLU, who argued on Khan Suri’s behalf Wednesday.

Khan Suri’s attorneys said his detention was “punitive in purpose” and a retaliatory measure for his advocacy for Gaza and association with his wife and her father, a government official in Gaza, during the hearing.

His wife, Mapheze Saleh, is a Palestinian American. Saleh is also a former employee of the Qatari-based news network Al Jazeera and the daughter of Ahmed Yousef, a former adviser to Ismail Haniyeh, a Hamas leader assassinated by Israel in Iran last year.

Khan Suri, who has not been charged with a crime, has been in the United States since 2022 on a valid visa. According to court documents, Khan Suri is a post-doctoral fellow and taught a course focused on South Asian minority rights at Georgetown.

The Trump administration revoked Khan Suri’s visa and accused him of having ties to Hamas, a terrorist organization. He was detained by masked federal officers outside his home in Rosslyn, Virginia, in March. He was moved across multiple state lines shortly after his arrest before being held in custody in a Texas detention center.

Saleh, who was in court during Wednesday’s proceedings, said her husband has told her he wears his detention “as a badge of honor” because he believes he was targeted because of his wife’s Palestinian background.

“Badar is a scholar, a researcher and a lover of freedom, truth and justice. I’m proud to be his wife and the mother of his three children,” Saleh said. “I’m a Palestinian woman who feels the pain of my people in Gaza. I’m also an American who believes in the freedom of speech. We are here in US, to live, to learn, to research and practice our profession, not to be separated as a family, not to be tortured, not to be disappeared, and definitely not to be to put in the detention center for no crime.”

by Gloria Pazmino and Emily R. Condon

CNN

5/15/25

https://www.cnn.com/2025/05/14/us/judge ... -khan-suri

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/69 ... i-v-trump/

Suri v. Trump (1:25-cv-00480)

District Court, E.D. Virginia

Last Updated: May 14, 2025, 3:58 p.m.

Assigned To: Patricia Tolliver Giles

Referred To: William B. Porter

64. May 14, 2025. Minute Entry for proceedings held before District Judge Patricia Tolliver Giles: Motions Hearing held on 5/14/2025.Appearances of Counsel for Petitioner and Counsel for Respondents.RE: 20 MOTION for Release on Bond filed by Badar Khan Suri - MATTER ARGUED AND GRANTED; 5 MOTION to compel respondents to return petitioner to this district filed by Badar Khan Suri - DENIED AS MOOT; Respondents Oral Motion to Stay Release DENIED. ORDER TO FOLLOW. Court Reporter: S. Wallace (pmil, ) (Entered: 05/14/2025)

65. May 14, 2025. ORDER, for the reasons stated in open court, Petitioner's 20 Motion for Release on Bond is GRANTED and Petitioner's 5 Motion to Compel Respondents to Return Petitioner to this District is DENIED as moot; Petitioner Dr. Khan Suri is to be immediately released on his personal recognizance during the pendency of his habeas proceedings subject to the following conditions: (see Order for details); Respondents shall not attempt to re-detain Petitioner without providing 48-hours notice to the Court and Petitioner's counsel; Respondent's request to stay this Court's decision pending appeal is DENIED. Signed by District Judge Patricia Tolliver Giles on 05/14/25. (pmil, ) (Entered: 05/14/2025)

Georgetown University post-doctoral fellow Badar Khan Suri has been ordered released by a US district judge in Virginia. Georgetown University

Georgetown University scholar Badar Khan Suri was released from a federal detention center in Texas on Wednesday, marking at least the third time a detained student or academic targeted by the Trump administration because of their protest activity or affiliation was released from immigration detention.

Earlier on Wednesday, US District Court Judge Patricia Tolliver Giles, issuing her ruling from the bench, said the government had failed to provide any evidence to continue to detain Khan Suri, who has been held in a Texas immigration detention facility for two months.

“I gave the government multiple opportunities to submit any type of filing to controvert these claims or support their opposition to these motions and they declined,” Tolliver Giles said.

The judge ordered Khan Suri’s release without bond, only requiring him to continue living in Virginia and to attend court proceedings in person. Khan Suri will be able to attend his deportation proceedings virtually, which are unfolding in Texas, Tolliver Giles said.

Badar Khan Suri (left) is photographed leaving US Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Prairieland Detention Facility in Alvarado, Texas on Wednesday. Phuong Tran/ACLU

Khan Suri is one of several non-citizen international scholars, faculty and students who have been detained or targeted for immigration enforcement as part of the Trump administration’s effort to target noncitizens who have participated in pro-Palestinian activism. Others include Mahmoud Khalil, Rümeysa Öztürk, Mohsen Madawi and Momodou Taal.

Last month, a Vermont judge ordered Columbia University student and permanent US resident Mohsen Mahdawi to be released. Mahdawi helped organize pro-Palestinian protests at Columbia and was detained during a citizenship appointment.

In Vermont last week, a judge ordered the release of Rümeysa Öztürk, a Turkish national and Tufts University student who was detained a year after she co-authored an op-ed in the school newspaper which was critical of the school’s response to the war in Gaza.

The cases have raised thorny legal questions about jurisdiction as well as First Amendment rights to free speech, which extend to both citizens and noncitizens under the US Constitution.

“He should have never been arrested and jailed for his constitutionally protected speech, just because our government disagrees with him,” said Sophia Gregg, an attorney for the ACLU, who argued on Khan Suri’s behalf Wednesday.

Khan Suri’s attorneys said his detention was “punitive in purpose” and a retaliatory measure for his advocacy for Gaza and association with his wife and her father, a government official in Gaza, during the hearing.

His wife, Mapheze Saleh, is a Palestinian American. Saleh is also a former employee of the Qatari-based news network Al Jazeera and the daughter of Ahmed Yousef, a former adviser to Ismail Haniyeh, a Hamas leader assassinated by Israel in Iran last year.

Khan Suri, who has not been charged with a crime, has been in the United States since 2022 on a valid visa. According to court documents, Khan Suri is a post-doctoral fellow and taught a course focused on South Asian minority rights at Georgetown.

The Trump administration revoked Khan Suri’s visa and accused him of having ties to Hamas, a terrorist organization. He was detained by masked federal officers outside his home in Rosslyn, Virginia, in March. He was moved across multiple state lines shortly after his arrest before being held in custody in a Texas detention center.

Saleh, who was in court during Wednesday’s proceedings, said her husband has told her he wears his detention “as a badge of honor” because he believes he was targeted because of his wife’s Palestinian background.

“Badar is a scholar, a researcher and a lover of freedom, truth and justice. I’m proud to be his wife and the mother of his three children,” Saleh said. “I’m a Palestinian woman who feels the pain of my people in Gaza. I’m also an American who believes in the freedom of speech. We are here in US, to live, to learn, to research and practice our profession, not to be separated as a family, not to be tortured, not to be disappeared, and definitely not to be to put in the detention center for no crime.”

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40037

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Ga

Gabbard fires officials who released memo contradicting Trump’s Venezuela gang claims. Two highest-ranking employees fired due to opposition to Trump, says Tulsi Gabbard’s office, without giving examples

by Coral Murphy Marcos and agency

Wed 14 May 2025 20.57 EDT

The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/202 ... ce-firings

Tulsi Gabbard, the US director of national intelligence, has fired the two highest-ranking officials at the National Intelligence Council (NIC) just weeks after the council released an assessment that contradicted Donald Trump’s justification for using the Alien Enemies Act to deport alleged Venezuelan gang members without due process.

Mike Collins was serving as acting chair of the NIC before he was dismissed alongside his deputy, Maria Langan-Riekhof. They each had more than 25 years of intelligence experience.

The two were fired because of their opposition to the US president, Gabbard’s office said in an email on Wednesday, without offering examples.

“The director is working alongside President Trump to end the weaponization and politicization of the intelligence community,” the office said.

The firings follow the release of a declassified memo from the NIC that found no coordination between Venezuela’s government and the Tren de Aragua gang. The Trump administration had given that as reasoning for invoking the Alien Enemies Act and deporting Venezuelan immigrants. The intelligence assessment was released in response to an open records request filed by the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

The latest round of intelligence firings comes as Gabbard and her team aim to eliminate what they view as bias and inefficiency within the intelligence community. On X, formerly Twitter, Gabbard’s deputy chief of staff, Alexa Henning, said the NIC officials, whom she referred to as “Biden holdovers”, were removed for “politicizing intelligence”.

While it’s not uncommon for new administrations to replace senior officials with their own picks, the firings of two respected intelligence officials who had served presidents of both parties have prompted concern. US congressman Jim Himes of Connecticut, the senior Democrat on the House intelligence committee, said he’s seen no details to explain the dismissals.

“Absent evidence to justify the firings, the workforce can only conclude that their jobs are contingent on producing analysis that is aligned with the President’s political agenda, rather than truthful and apolitical,” Himes said in a statement.

Though it’s not widely known to the public, the NIC plays a key role in the country’s spy services, helping combine intelligence gathered from different agencies into comprehensive assessments used by the White House and senior national security officials.

Collins was considered one of the intelligence service’s top authorities on East Asia. Langan-Riekhof has served as a senior analyst and director of the CIA’s strategic insight department and is an expert on the Middle East.

Attempts to reach both were unsuccessful on Wednesday. The CIA declined to comment publicly, citing personnel matters.

Gabbard also is consolidating some of the intelligence community’s key operations, moving some offices now located at the CIA to buildings for the office of the director of national intelligence (ODNI), her office said. They include the NIC as well as the staff who prepare the president’s daily brief, the report to the president that contains the most important intelligence and national security information.

The move will give Gabbard more direct control over the brief. While the brief is already ODNI’s responsibility, the CIA has long played a significant role in its preparation, providing physical infrastructure and staffing that will have to be moved to ODNI or recreated.

Gabbard oversees and coordinates the work of 18 federal intelligence agencies. She has worked to reshape the intelligence community – eliminating diversity, equity and inclusion programs under Trump’s orders and creating a taskforce to examine ways to cut costs and consider whether to declassify material relating to Covid-19 and other topics.

Gabbard also has vowed to investigate intelligence leaks and end what she said was the misuse of intelligence for political aims.

The Associated Press contributed reporting

by Coral Murphy Marcos and agency

Wed 14 May 2025 20.57 EDT

The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/202 ... ce-firings

Tulsi Gabbard, the US director of national intelligence, has fired the two highest-ranking officials at the National Intelligence Council (NIC) just weeks after the council released an assessment that contradicted Donald Trump’s justification for using the Alien Enemies Act to deport alleged Venezuelan gang members without due process.

Mike Collins was serving as acting chair of the NIC before he was dismissed alongside his deputy, Maria Langan-Riekhof. They each had more than 25 years of intelligence experience.

The two were fired because of their opposition to the US president, Gabbard’s office said in an email on Wednesday, without offering examples.

“The director is working alongside President Trump to end the weaponization and politicization of the intelligence community,” the office said.

The firings follow the release of a declassified memo from the NIC that found no coordination between Venezuela’s government and the Tren de Aragua gang. The Trump administration had given that as reasoning for invoking the Alien Enemies Act and deporting Venezuelan immigrants. The intelligence assessment was released in response to an open records request filed by the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

The latest round of intelligence firings comes as Gabbard and her team aim to eliminate what they view as bias and inefficiency within the intelligence community. On X, formerly Twitter, Gabbard’s deputy chief of staff, Alexa Henning, said the NIC officials, whom she referred to as “Biden holdovers”, were removed for “politicizing intelligence”.

While it’s not uncommon for new administrations to replace senior officials with their own picks, the firings of two respected intelligence officials who had served presidents of both parties have prompted concern. US congressman Jim Himes of Connecticut, the senior Democrat on the House intelligence committee, said he’s seen no details to explain the dismissals.

“Absent evidence to justify the firings, the workforce can only conclude that their jobs are contingent on producing analysis that is aligned with the President’s political agenda, rather than truthful and apolitical,” Himes said in a statement.

Though it’s not widely known to the public, the NIC plays a key role in the country’s spy services, helping combine intelligence gathered from different agencies into comprehensive assessments used by the White House and senior national security officials.

Collins was considered one of the intelligence service’s top authorities on East Asia. Langan-Riekhof has served as a senior analyst and director of the CIA’s strategic insight department and is an expert on the Middle East.

Attempts to reach both were unsuccessful on Wednesday. The CIA declined to comment publicly, citing personnel matters.

Gabbard also is consolidating some of the intelligence community’s key operations, moving some offices now located at the CIA to buildings for the office of the director of national intelligence (ODNI), her office said. They include the NIC as well as the staff who prepare the president’s daily brief, the report to the president that contains the most important intelligence and national security information.

The move will give Gabbard more direct control over the brief. While the brief is already ODNI’s responsibility, the CIA has long played a significant role in its preparation, providing physical infrastructure and staffing that will have to be moved to ODNI or recreated.

Gabbard oversees and coordinates the work of 18 federal intelligence agencies. She has worked to reshape the intelligence community – eliminating diversity, equity and inclusion programs under Trump’s orders and creating a taskforce to examine ways to cut costs and consider whether to declassify material relating to Covid-19 and other topics.

Gabbard also has vowed to investigate intelligence leaks and end what she said was the misuse of intelligence for political aims.

The Associated Press contributed reporting

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40037

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Ga

https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/ ... ezuela.pdf

Approved for release by ODNI on 5/5/2025, Case No. DF-2025-00379

NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE COUNCIL

SENSE OF THE COMMUNITY MEMORANDUM

7 April 2025 SOCM 2025-11374

(b)(3) [DELETE] Venezuela: Examining Regime Ties to Tren de Aragua

* (U) This assessment was prepared under the auspices of the National Intelligence Officer (NIO) for Western Hemisphere. It was drafted by the National Intelligence Council (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. Classified By: (b)(3) [DELETE] Derived From: (b)(3) [DELETE] Declassify On: (b)(3) [DELETE] (b)(3) [DELETE]

(b)(3) [DELETE] Tren de Aragua (TDA) is a transnational gang based in Venezuela that has spread to at least seven South America and Caribbean countries, operating in loosely-organized cells of localized, individual criminal networks. TDA leaders have historically been located and broadly benefitted from various permissive conditions and incapacities in Venezuela. They probably communicate to varying degrees with some TDA cells in other countries, although other cells probably operate and coordinate amongst themselves independently, judging from DHS reporting (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. Some self-described TDA criminal entities or individuals lack direct ties to TDA leadership but still use the TDA moniker for reputational benefits, complicating the IC’s ability to identify and track authentic group members and networks.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] TDA formed around 2007 in the Tocoron Prison located in Aragua State, Venezuela, which served as its initial base of operations. The group’s senior founders and probable core leaders are Hector Guerrero Flores, a.k.a. Nino Guerrero or El Nino, Yohan Jose Romero a.k.a. Johan Petrica, and Larry Alvarez Nunez, a.k.a. Larry Changa. Alvarez Nunez is in Colombian custody.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] In recent years, TDA leadership has faced setbacks, including losing their centralized location in Tocoron Prison and having several senior TDA leaders arrested in Colombia by the Colombian National Police. In 2023, the Venezuelan regime cleared TDA from Tocoron Prison, although the group’s leaders were able to escape in the operation, possibly assisted by low-level Venezuelan military and political leaders, judging from DHS reporting. The regime may have expelled TDA from the prison to undercut regional press alleging TDA ties to disputed Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, or to disrupt further destabilizing activities by gang members inside Venezuela.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] TDA and other Venezuelan organized criminal groups have spread to other countries, aided by the movement of the larger body of Venezuelan migrants into Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, and the United States, in particular. Nicaragua and Panama have also reported encountering TDA affiliates, (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. From 2021 to 2024 there was a spike in Venezuelan encounters at the US-Mexico border, in which some TDA members could have been present as they have generally moved with Venezuelan migrant communities and profit from human trafficking and migrant smuggling. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. The small size of TDA’s cells, its focus on low-skill criminal activities, and its decentralized structure make it highly unlikely that TDA coordinates large volumes of human trafficking or migrant smuggling.

(b)(3) [DELETE] Maduro Regime Probably Maintains Ad Hoc Links to Some Criminal Groups in Venezuela

(b)(3) [DELETE] Maduro regime leadership probably sometimes tolerates TDA's presence in Venezuela, and some government officials may cooperate with TDA for financial gain. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] instances of regime officials' cooperation with various armed and criminal groups, such as Colombia's National Liberation Army or Los Colectivos, have been ad-hoc and reportedly driven by the regime's desire for help controlling territory or deterring a perceived threat of invasion, or for individual financial gain.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] The Madura regime generally does not impede illegal armed and criminal groups from operating in Venezuela, but it does combat and seek to contain them when it fears they could destabilize the regime or when corrupt deals sour. Venezuela 's security services lack the capacity to fully control Venezuelan territory, giving the regime an interest in cooperating with armed groups for insight and control in areas outside the services' traditional areas of operation. Furthermore, combatting such groups often results in personnel losses, probably encouraging the regime to at times cooperate with some groups instead of contesting them.

• b)(3) [DELETE] Some mid- to low-level Venezuelan officials probably profit from TDA's illicit activities, according to (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] and press reporting. For example, local military officials have alerted other armed and criminal groups conducting aerial drug shipments to Venezuelan Air Force patrols and might have alerted TDA leadership of a planned raid in 2023 against the prison that was its base of operations.

(b)(3) [DELETE] Maduro Regime Probably Not Directing TDA Activities

(b)(3) [DELETE] While Venezuela's permissive environment enables TDA to operate, the Maduro regime probably does not have a policy of cooperating with TDA and is not directing TDA movement to and operations in the United States. The IC bases this judgment on Venezuelan law enforcement actions demonstrating the regime treats TDA as a threat; an uneasy mix of cooperation and confrontation rather than top-down directives characterizing the regime's ties to other armed groups; and the decentralized makeup of TDA that would make such a relationship logistically challenging. Furthermore, most of the IC judges that intelligence indicating that regime leaders are directing or enabling TDA migration to the United States is not credible and would need (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] reporting (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] corroborated (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. While FBI analysts agree with the above assessment, they assess some Venezuelan government officials facilitate TDA members' migration from Venezuela to the United States and use members as proxies in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and the United States to advance what they see as the Maduro regime's goal of destabilizing governments and undermining public safety in these countries, based on DHS and FBI reporting as of February 2024.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] Venezuelan intelligence, military, and police services view TDA as a security threat (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] and operate against it in ways that make it highly unlikely the two sides would cooperate in a strategic or consistent way, according to (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] and press reporting (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. In late January, at least two Venezuelan National Guard units arrested TDA members in Venezuela in separate operations.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] Since at least 2016, Venezuelan security forces have periodically engaged in armed confrontations with TDA, resulting in the killing of some TDA members, according to (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE].

• (b)(3) [DELETE] The IC has not observed the regime directing TDA, including to push migrants to the United States, which probably would require extensive (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] coordination and funding between regime entities and TDA leaders that we would collect. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. The IC also recognizes the regime appreciates migration as a safety valve, allowing discontented Venezuelans to leave. US border encounters of Venezuelan national have decreased since January because of migrant perceptions of new US enforcement policies. Since late January, border encounters have plummeted more than 80 percent, according to (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] reaching the lowest level in decades.

• (b)(3) [DELETE]. The limited IC reporting suggesting a link between TDA and some Venezuelan officials aimed at facilitating TDA migration to the United States (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. In some cases, reporting warns that these sources could also be motivated to fabricate information. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE].

(b)(3) [DELETE]. Some regime officials are probably willing to capitalize on migration flows for personal financial or other benefits, even though the Maduro regime probably is not systematically directing Venezuelan outflows, such as to sow chaos in receiving countries. The intelligence record indicates Venezuelans have migrated voluntarily, often at great personal risk, to flee political instability and near-collapse of Venezuela's economy. The IC attributes increased migration flows, including the spike in US arrivals from 2021 to 2024 (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] of Venezuelan nationals -- which could include some TDA members -- to a variety of push and pull factors, including socioeconomic conditions, family ties to the United States, and migrants' perceptions of US and regional enforcement. At the same time, Maduro has not taken meaningful steps to curb migration, highlighting his partial accountability, probably because it has helped him retain power by having dissidents leave the country, increasing remittances to Venezuela that help ease economic strains for remaining populations, and allowing the regime to spend less on social services. The Maduro regime may have also welcomed the logistical, financial, and political headaches that unregulated migration has caused for the US Government, its perceived principal adversary, even if not a principal intent.

• (b)(3) [DELETE]. Since 2014, an estimated 7.8 million Venezuelans have departed their country, with roughly 6.6 million now residing in Latin America and the Caribbean as of late 2024. Increased migration flows have coincided with periods of acute political and economic instability in Venezuela, and irritated regional receiving countries, including neighboring Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Most Venezuelan migrants, including those traveling to the United States and in the region, seek more stable economic and political environments, judging from surveys and interviews with regional and US-bound Venezuelan migrants.

• (b)(3) [DELETE]. The lack of transparency and accountability in Venezuela has created an environment for widespread corruption and for regime officials to benefit from a variety of illicit activities, an environment fueled by Maduro's illegitimate and autocratic grip on power. This persistent outflow of migrants probably offers opportunities for some regime officials in capacities to facilitate migration movement to look for and receive personal kickbacks for their services, and to conceal the benefits they receive.

(b)(3) [DELETE] Potential Indicators of a Change in the Maduro Regime-TDA Relationship

(b)(3) [DELETE] The IC is closely tracking key indicators of any shift in the relationship between the Maduro regime and TDA, including (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] weapons transfers, (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. If the regime's relationship with the group became more cooperative, the IC would expect to see most regime operations against TDA to cease and some indication that the regime was providing TDA state resources. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE].

• (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]

• (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. Local press provides some insight on potential ties between the regime and TDA, but the IC typically does not rely solely on such media given the highly polarized media environment.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] US law enforcement reporting has the most focus on TDA and its activities in the United States because of its unique legal collection authorities among IC components. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE].

• (b)(3) [DELETE]. The next event that may shed light on regime ties to TDA involves the legal case in 2023 of a junior Venezuelan military officer who escaped imprisonment in Venezuela after he participated in coup plotting against the regime and was killed in Chile in 2024. Last week, Chilean officials took the case to the international Criminal Court (ICC), alleging the Maduro regime is involved in the killing, acting via TDA. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE].

• (b)(3) [DELETE]

Approved for release by ODNI on 5/5/2025, Case No. DF-2025-00379

NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE COUNCIL

SENSE OF THE COMMUNITY MEMORANDUM

7 April 2025 SOCM 2025-11374

(b)(3) [DELETE] Venezuela: Examining Regime Ties to Tren de Aragua

* (U) This assessment was prepared under the auspices of the National Intelligence Officer (NIO) for Western Hemisphere. It was drafted by the National Intelligence Council (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. Classified By: (b)(3) [DELETE] Derived From: (b)(3) [DELETE] Declassify On: (b)(3) [DELETE] (b)(3) [DELETE]

(b)(3) [DELETE] Tren de Aragua (TDA) is a transnational gang based in Venezuela that has spread to at least seven South America and Caribbean countries, operating in loosely-organized cells of localized, individual criminal networks. TDA leaders have historically been located and broadly benefitted from various permissive conditions and incapacities in Venezuela. They probably communicate to varying degrees with some TDA cells in other countries, although other cells probably operate and coordinate amongst themselves independently, judging from DHS reporting (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. Some self-described TDA criminal entities or individuals lack direct ties to TDA leadership but still use the TDA moniker for reputational benefits, complicating the IC’s ability to identify and track authentic group members and networks.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] TDA formed around 2007 in the Tocoron Prison located in Aragua State, Venezuela, which served as its initial base of operations. The group’s senior founders and probable core leaders are Hector Guerrero Flores, a.k.a. Nino Guerrero or El Nino, Yohan Jose Romero a.k.a. Johan Petrica, and Larry Alvarez Nunez, a.k.a. Larry Changa. Alvarez Nunez is in Colombian custody.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] In recent years, TDA leadership has faced setbacks, including losing their centralized location in Tocoron Prison and having several senior TDA leaders arrested in Colombia by the Colombian National Police. In 2023, the Venezuelan regime cleared TDA from Tocoron Prison, although the group’s leaders were able to escape in the operation, possibly assisted by low-level Venezuelan military and political leaders, judging from DHS reporting. The regime may have expelled TDA from the prison to undercut regional press alleging TDA ties to disputed Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, or to disrupt further destabilizing activities by gang members inside Venezuela.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] TDA and other Venezuelan organized criminal groups have spread to other countries, aided by the movement of the larger body of Venezuelan migrants into Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, and the United States, in particular. Nicaragua and Panama have also reported encountering TDA affiliates, (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. From 2021 to 2024 there was a spike in Venezuelan encounters at the US-Mexico border, in which some TDA members could have been present as they have generally moved with Venezuelan migrant communities and profit from human trafficking and migrant smuggling. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. The small size of TDA’s cells, its focus on low-skill criminal activities, and its decentralized structure make it highly unlikely that TDA coordinates large volumes of human trafficking or migrant smuggling.

(b)(3) [DELETE] Maduro Regime Probably Maintains Ad Hoc Links to Some Criminal Groups in Venezuela

(b)(3) [DELETE] Maduro regime leadership probably sometimes tolerates TDA's presence in Venezuela, and some government officials may cooperate with TDA for financial gain. (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] instances of regime officials' cooperation with various armed and criminal groups, such as Colombia's National Liberation Army or Los Colectivos, have been ad-hoc and reportedly driven by the regime's desire for help controlling territory or deterring a perceived threat of invasion, or for individual financial gain.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] The Madura regime generally does not impede illegal armed and criminal groups from operating in Venezuela, but it does combat and seek to contain them when it fears they could destabilize the regime or when corrupt deals sour. Venezuela 's security services lack the capacity to fully control Venezuelan territory, giving the regime an interest in cooperating with armed groups for insight and control in areas outside the services' traditional areas of operation. Furthermore, combatting such groups often results in personnel losses, probably encouraging the regime to at times cooperate with some groups instead of contesting them.

• b)(3) [DELETE] Some mid- to low-level Venezuelan officials probably profit from TDA's illicit activities, according to (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] and press reporting. For example, local military officials have alerted other armed and criminal groups conducting aerial drug shipments to Venezuelan Air Force patrols and might have alerted TDA leadership of a planned raid in 2023 against the prison that was its base of operations.

(b)(3) [DELETE] Maduro Regime Probably Not Directing TDA Activities

(b)(3) [DELETE] While Venezuela's permissive environment enables TDA to operate, the Maduro regime probably does not have a policy of cooperating with TDA and is not directing TDA movement to and operations in the United States. The IC bases this judgment on Venezuelan law enforcement actions demonstrating the regime treats TDA as a threat; an uneasy mix of cooperation and confrontation rather than top-down directives characterizing the regime's ties to other armed groups; and the decentralized makeup of TDA that would make such a relationship logistically challenging. Furthermore, most of the IC judges that intelligence indicating that regime leaders are directing or enabling TDA migration to the United States is not credible and would need (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] reporting (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] corroborated (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. While FBI analysts agree with the above assessment, they assess some Venezuelan government officials facilitate TDA members' migration from Venezuela to the United States and use members as proxies in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and the United States to advance what they see as the Maduro regime's goal of destabilizing governments and undermining public safety in these countries, based on DHS and FBI reporting as of February 2024.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] Venezuelan intelligence, military, and police services view TDA as a security threat (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] and operate against it in ways that make it highly unlikely the two sides would cooperate in a strategic or consistent way, according to (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE] and press reporting (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE]. In late January, at least two Venezuelan National Guard units arrested TDA members in Venezuela in separate operations.

• (b)(3) [DELETE] Since at least 2016, Venezuelan security forces have periodically engaged in armed confrontations with TDA, resulting in the killing of some TDA members, according to (b)(1), (b)(3) [DELETE].