Donald J Trump

@ real Donald Trump

He who saves his country does not violate any law

******

Donald J Trump

@ real Donald Trump

Should I audit the IRS into Oblivion?

10:11 AM

February 15, 2025

Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Gates

Re: Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Ga

NDP MP Charlie Angus urges Canadian response to Trump threats

by cpac

February 14, 2025

NDP MP Charlie Angus is joined by Fareed Khan (Canadians United Against Hate) and Anne Lagacé Dowson (Canadian Health Coalition) at a news conference on Parliament Hill. On the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the adoption of the Canadian flag, they are calling on Canadians to respond to United States President Donald Trump's recent threats concerning possible tariffs on Canadian goods or the possible annexation of Canada by the U.S.

Transcript @ 3:03

[Fareed Khan (Canadians United Against Hate)] Thank you. And thank you Charlie for having me here.

I'd like to acknowledge that we are speaking from the unceded territory of the Algonquin Nishnawbe Aski people. My name is Fareed Khan. I'm a human rights activist, an anti-hate activist, and the founder of the advocacy group Canadians United Against Hate.

Tomorrow, February 15th, is Canada's flag day. It marks the 60th anniversary of the adoption of the red and white Maple Leaf flag, a symbol of Canada recognized around the world, and a symbol that Canadians are very proud to display.

As we mark this occasion, we're reminded of the values that have made Canada a beacon of hope and freedom. But today, we're also reminded of the very real threat hanging over our country, the threat of Donald Trump and his fascist and racist ambitions.

I'm here to speak today as a Canadian citizen, as an immigrant, as a child of refugee parents. I'm here to speak for the millions of Canadians who are watching with alarm as Canada-U.S. relations worsen day by day, with every new word that comes out of the mouth of Donald Trump as he refers to Canada. And because of Trump's threats to wreck Canada's economy, and annex us as the 51st state. I'm here to say to Donald Trump and his MAGA cultists that Canada will never become part of the U.S., and it'll only happen when hell freezes is over and all Canadians are gone from this land.

For my entire life, Canada has stood tall as a nation that values diversity, equity, and inclusion. But with Trump's threats, these values are also under threat. A vision of the future under Trump can be seen in the fascist edicts that have come out of his office which target migrants, refugees, the lgbtq community, women, Muslims, and vulnerable minorities; edicts which perpetuate hate, bigotry, misogyny, transphobia, and xenophobia, and violate fundamental human rights.

And make no mistake, Trump is a fascist. That's not my assessment, but that of 11 former high-ranking officials from his previous administration, including his longest serving chief of staff, and his former chief of defense staff.

My parents, and millions of others, chose to immigrate to Canada because of its values and the economic opportunities it presented. They chose to settle here, over other nations, because they wanted their children to be Canadian -- not American! And so it's only natural that immigrants, along with all patriotic Canadians, stand up and defend our country against Trump's unofficial Declaration of War, which is what his threats to impose 25% tariffs, and annex Canada are. Trump's repeated comments about annexing Canada, and his actions, reveal a sociopathy that was described in detail in the 2017 book "The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump." In it, 27 psychiatrists and mental health professionals made it clear that Trump is a sociopath who poses a threat not just to the U.S., but to the entire world. Some of the assessments of Trump's personality in the book include the following -- and mind you, these are assessments made by professionals who work in the area of mental health. "Trump is an impulsive, immature, incompetent person who, when in the position of ultimate power, would easily slide into the role of tyrant. His sociopathic characteristics are undeniable ,and present a profound threat to democracy. He is profoundly an evil man, exhibiting malignant narcissism. And if left unchecked, his pathological narcissism could lead to World War III.

I would encourage members of the media who haven't looked at this book to please take a look at it, and get a real look into the kind of person that Donald Trump is, if you don't know already from the insanity that comes out of his mouth.

To our political leaders I say, Canada cannot engage with him as we do with other normal leaders. He has shown himself to be an enemy to Canada, and we have to treat him as a clear and present danger to our country, and to our allies.

And to the Canadian media I say, "Begin telling the story of the fascist sociopath occupying the White House using that language, so that Canadians in the world know the very real danger he presents to peace and stability.

Dring World War II, over 45,000 Canadian soldiers, sailors, and airmen paid the ultimate price to defend Canada from a fascist threat, as did millions of others from Allied Nations. Let's not let those sacrifices be in vain as we face another fascist threat today.

And as we Mark the 60th anniversary of the Canadian flag, all Canadians who say that they love Canada, who want to continue to build the just society that Pierre Trudeau spoke of over 50 years ago, who want to protect our communities from the fascist, racist, misogynistic, and transphobic demagogue that is trying to destroy Canada, we need to stand together and defend our flag, our country, and our sovereignty. Thank you. [Charlies Angus] Good morning, and happy Valentine's Day. I want to say this morning how much I love my country. We don't tend to do that in Canada. We think that that's kind of gauche. We don't feel we need to say how much we love our country. But when we see the criminal gang that is taking control in Washington telling us we do not have a right to our nation, well, oh yeah, not only am I going to love my country, and its values, and the people from one end of this beautiful Nation to another, but I'm going to work with those ordinary Canadians to defend our right to continue to exist as an independent nation.

And for this, on the eve of the 60th anniversary of the Canadian flag, I encourage Canadians to reflect what that symbol means; that symbol that has been in war zones; that symbol that has been since Canadians went to fight famines in other countries; that symbol of openness and inclusion that is the direct opposite to the politics of Elon Musk and Donald Trump.

This week we saw the shameful actions by Donald Trump to negotiate with Vladimir Putin -- another gangster -- to sell the people of Ukraine out. Mr Putin thinks that Vladimir Putin is a savvy genius, and he detests our country? Well, he's sending us a very clear message of the kind of man he is. Our neighbors are no longer our allies. We are dealing with a regime next door to us that is ignoring the international rule of law. And we have to take this dead serious, as a nation with our political leaders, but with ordinary Canadians.

So what do we do right now? Well, I'm extremely encouraged by the incredible response we've received from this Pledge For Canada that's now, just in the space of two weeks, had over 62,000 people sign up, people from across the political spectrum. Former Prime Minister Kim Campbell, former Attorney General Alan Rock, former Premier Danny Williams, but also the incredible artists and indigenous activists, and labor activists, and ordinary people across this country who said that there's a value to our nation that we're willing to defend.

And I also want to encourage and thank the ordinary people who, on their own, began the boycott of all things American.

Now some might think well, you know, if you just choose not to go down to Tennessee this year, who's going to notice? Well, right now, we're seeing the American tourism industry is in full-on panic. There are now over $2 billion in travel that is at risk. That's 140,000 American jobs. That's if just 10% of Canadians cancel their trips. It's still too early to say how many are cancelling, but from the evidence that we're gathering, it's much much higher than 10%.

And it's about sending a message, sending a message to Texas governor Greg Abbot who said Canada was going to learn a lesson. Oh really? Texas is going to teach Canada a lesson? Well, we've got $400 Million worth of travel that goes to Texas Mr. Abbott. How about we teach you a lesson, and say we got better places to go than Texas? If that's your attitude of Canadians, we will not go. Hell no we will not go.

The boycott is going to target many many areas of the United States that are very vulnerable right now. Kentucky has already started to speak up about the huge losses that they're facing in Kentucky bourbon, and Kentucky whiskey, because their No. 1 market is Canadians. So when Canadians stop buying, it's sending a message. And we know this is the only way right now that Americans are going to be able to put pressure on Donald Trump. Because what's at risk here, is the future of an international order, where we respect the rights of countries to be independent; we respect the international rule of law; we respect our neighbors and borders. And this is something Mr. Trump is saying he will not respect.

So on this Festival where we celebrate Canada as a nation and our flag, I am encouraged. I want to thank Canadians. I want to say we are strong; we do not bend; and we will never ever ever kiss the ring of that gangster from Mar-a-Lago.

So let's celebrate this 60th anniversary for Canada, and our flag, in a way that we have never done before.

Thank you. Merci. We'll take any questions.

Q. Mr. Angus, we've heard from you before this idea that you'd like to see your party continue to be able to work with the Liberals to keep Parliament going. Is that your view still, that you'd like to see whoever becomes the next prime minister to strike a deal with the NDP to keep Parliament moving?

[Charlie Angus] Since January 6th, the world for Canada's turned upside down. We are in completely uncharted territory. And nobody can say they have a plan to deal with this: none of our Comm's teams; none of our political planners; there's not a politician who's ready to deal with the crisis, because this is the biggest crisis we've seen since the 1930s.

So my simple position as a member of Parliament is to encourage all Parliamentarians to say, "Let's go back to Parliament. Let's see if we can put a plan in place to get Canada through this period. There will be lots of time to to bicker and batter as we love to do. But right now I think my focus is Canada.

Q. On the topic that my colleague just brought up, a little bit of a different focus. Is now perhaps the right time for an early election given the uncertainty surrounding Donald Trump and his administration and the threat of tariffs?

[Charlie Angus] I think what people were thinking on January 1st, and what people saw after January 6th, our world has turned upside down. And we see that Mr. Trump is continuing to attack and menace not just Canada, but the international order. I'm just one Parliamentarian, and I'm ready to go back to Parliament and make it work. I'm willing to do whatever I have to to try and put a plan in place to help Canada get through this. Maybe there will be an election, maybe there won't, but I think we all have an obligation right now to try to reassure Canadians that we are there for them, and that we will do our job to get through what is unprecedented turbulence....'

My focus right now is what do we do to go back to Parliament and try and get a plan for Canadians? That is where we have to stay focused right now.

I think we have to go back and say, "What is it going to mean to work as a Parliament to put in place, the measures at the federal level to withstand the threat, not just economic threats, but the threats to the international order; the threats that we're seeing to NATO; the threats to our sovereignty? There's so many things that we could be doing. But to do that we all have to agree that right now Canada's primary focus needs to be Canada.

Q. So the Trump tariff threats kind of spark some conversations that a lot of our oil is flowing north to south rather than east-west, and to ports, I guess, and it's exposed a weakness in Canadian energy. Some complain that NDP standards stood in the way of these pipelines, as well as some First Nations. What you think about that. Would you be willing to work more to get some of these projects going forward?

[Charlie Angus] Well, it's amazing, you know -- never give up a good opportunity to burn the planet when there's a crisis. Canadians paid $34 billion dollars to build a pipeline. Canadians are subsidizing over 50 cents on every dollar for the pipeline. To be told that Canada hasn't done its share? Why aren't we talking about the huge opportunities to reinvest across the board with energy? The idea that we're going to spend 15 years building a pipeline to oppose Pump-Trump, when we've just built a pipeline, I'd like to see what the oil sector is going to do. They're making record profits, and I haven't seen them offer to do anything yet, except we've seen Madame Smith say that any efforts to have oil and the energy sector play their part, is some kind of threat to Canada.

So this is all speculation. But there's huge things that we could do across our regions that we'd get bigger bang for the bucks. So if they want to post trial balloons, go ahead. But I think there's many opportunities we can have to make a resilient economy right now in the short term.

[Hostess] Thank you. This concludes the press conference.

[Charlie Angus] Thank you.

by cpac

February 14, 2025

NDP MP Charlie Angus is joined by Fareed Khan (Canadians United Against Hate) and Anne Lagacé Dowson (Canadian Health Coalition) at a news conference on Parliament Hill. On the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the adoption of the Canadian flag, they are calling on Canadians to respond to United States President Donald Trump's recent threats concerning possible tariffs on Canadian goods or the possible annexation of Canada by the U.S.

Transcript @ 3:03

[Fareed Khan (Canadians United Against Hate)] Thank you. And thank you Charlie for having me here.

I'd like to acknowledge that we are speaking from the unceded territory of the Algonquin Nishnawbe Aski people. My name is Fareed Khan. I'm a human rights activist, an anti-hate activist, and the founder of the advocacy group Canadians United Against Hate.

Tomorrow, February 15th, is Canada's flag day. It marks the 60th anniversary of the adoption of the red and white Maple Leaf flag, a symbol of Canada recognized around the world, and a symbol that Canadians are very proud to display.

As we mark this occasion, we're reminded of the values that have made Canada a beacon of hope and freedom. But today, we're also reminded of the very real threat hanging over our country, the threat of Donald Trump and his fascist and racist ambitions.

I'm here to speak today as a Canadian citizen, as an immigrant, as a child of refugee parents. I'm here to speak for the millions of Canadians who are watching with alarm as Canada-U.S. relations worsen day by day, with every new word that comes out of the mouth of Donald Trump as he refers to Canada. And because of Trump's threats to wreck Canada's economy, and annex us as the 51st state. I'm here to say to Donald Trump and his MAGA cultists that Canada will never become part of the U.S., and it'll only happen when hell freezes is over and all Canadians are gone from this land.

For my entire life, Canada has stood tall as a nation that values diversity, equity, and inclusion. But with Trump's threats, these values are also under threat. A vision of the future under Trump can be seen in the fascist edicts that have come out of his office which target migrants, refugees, the lgbtq community, women, Muslims, and vulnerable minorities; edicts which perpetuate hate, bigotry, misogyny, transphobia, and xenophobia, and violate fundamental human rights.

And make no mistake, Trump is a fascist. That's not my assessment, but that of 11 former high-ranking officials from his previous administration, including his longest serving chief of staff, and his former chief of defense staff.

My parents, and millions of others, chose to immigrate to Canada because of its values and the economic opportunities it presented. They chose to settle here, over other nations, because they wanted their children to be Canadian -- not American! And so it's only natural that immigrants, along with all patriotic Canadians, stand up and defend our country against Trump's unofficial Declaration of War, which is what his threats to impose 25% tariffs, and annex Canada are. Trump's repeated comments about annexing Canada, and his actions, reveal a sociopathy that was described in detail in the 2017 book "The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump." In it, 27 psychiatrists and mental health professionals made it clear that Trump is a sociopath who poses a threat not just to the U.S., but to the entire world. Some of the assessments of Trump's personality in the book include the following -- and mind you, these are assessments made by professionals who work in the area of mental health. "Trump is an impulsive, immature, incompetent person who, when in the position of ultimate power, would easily slide into the role of tyrant. His sociopathic characteristics are undeniable ,and present a profound threat to democracy. He is profoundly an evil man, exhibiting malignant narcissism. And if left unchecked, his pathological narcissism could lead to World War III.

I would encourage members of the media who haven't looked at this book to please take a look at it, and get a real look into the kind of person that Donald Trump is, if you don't know already from the insanity that comes out of his mouth.

To our political leaders I say, Canada cannot engage with him as we do with other normal leaders. He has shown himself to be an enemy to Canada, and we have to treat him as a clear and present danger to our country, and to our allies.

And to the Canadian media I say, "Begin telling the story of the fascist sociopath occupying the White House using that language, so that Canadians in the world know the very real danger he presents to peace and stability.

Dring World War II, over 45,000 Canadian soldiers, sailors, and airmen paid the ultimate price to defend Canada from a fascist threat, as did millions of others from Allied Nations. Let's not let those sacrifices be in vain as we face another fascist threat today.

And as we Mark the 60th anniversary of the Canadian flag, all Canadians who say that they love Canada, who want to continue to build the just society that Pierre Trudeau spoke of over 50 years ago, who want to protect our communities from the fascist, racist, misogynistic, and transphobic demagogue that is trying to destroy Canada, we need to stand together and defend our flag, our country, and our sovereignty. Thank you. [Charlies Angus] Good morning, and happy Valentine's Day. I want to say this morning how much I love my country. We don't tend to do that in Canada. We think that that's kind of gauche. We don't feel we need to say how much we love our country. But when we see the criminal gang that is taking control in Washington telling us we do not have a right to our nation, well, oh yeah, not only am I going to love my country, and its values, and the people from one end of this beautiful Nation to another, but I'm going to work with those ordinary Canadians to defend our right to continue to exist as an independent nation.

And for this, on the eve of the 60th anniversary of the Canadian flag, I encourage Canadians to reflect what that symbol means; that symbol that has been in war zones; that symbol that has been since Canadians went to fight famines in other countries; that symbol of openness and inclusion that is the direct opposite to the politics of Elon Musk and Donald Trump.

This week we saw the shameful actions by Donald Trump to negotiate with Vladimir Putin -- another gangster -- to sell the people of Ukraine out. Mr Putin thinks that Vladimir Putin is a savvy genius, and he detests our country? Well, he's sending us a very clear message of the kind of man he is. Our neighbors are no longer our allies. We are dealing with a regime next door to us that is ignoring the international rule of law. And we have to take this dead serious, as a nation with our political leaders, but with ordinary Canadians.

So what do we do right now? Well, I'm extremely encouraged by the incredible response we've received from this Pledge For Canada that's now, just in the space of two weeks, had over 62,000 people sign up, people from across the political spectrum. Former Prime Minister Kim Campbell, former Attorney General Alan Rock, former Premier Danny Williams, but also the incredible artists and indigenous activists, and labor activists, and ordinary people across this country who said that there's a value to our nation that we're willing to defend.

And I also want to encourage and thank the ordinary people who, on their own, began the boycott of all things American.

Now some might think well, you know, if you just choose not to go down to Tennessee this year, who's going to notice? Well, right now, we're seeing the American tourism industry is in full-on panic. There are now over $2 billion in travel that is at risk. That's 140,000 American jobs. That's if just 10% of Canadians cancel their trips. It's still too early to say how many are cancelling, but from the evidence that we're gathering, it's much much higher than 10%.

And it's about sending a message, sending a message to Texas governor Greg Abbot who said Canada was going to learn a lesson. Oh really? Texas is going to teach Canada a lesson? Well, we've got $400 Million worth of travel that goes to Texas Mr. Abbott. How about we teach you a lesson, and say we got better places to go than Texas? If that's your attitude of Canadians, we will not go. Hell no we will not go.

The boycott is going to target many many areas of the United States that are very vulnerable right now. Kentucky has already started to speak up about the huge losses that they're facing in Kentucky bourbon, and Kentucky whiskey, because their No. 1 market is Canadians. So when Canadians stop buying, it's sending a message. And we know this is the only way right now that Americans are going to be able to put pressure on Donald Trump. Because what's at risk here, is the future of an international order, where we respect the rights of countries to be independent; we respect the international rule of law; we respect our neighbors and borders. And this is something Mr. Trump is saying he will not respect.

So on this Festival where we celebrate Canada as a nation and our flag, I am encouraged. I want to thank Canadians. I want to say we are strong; we do not bend; and we will never ever ever kiss the ring of that gangster from Mar-a-Lago.

So let's celebrate this 60th anniversary for Canada, and our flag, in a way that we have never done before.

Thank you. Merci. We'll take any questions.

Q. Mr. Angus, we've heard from you before this idea that you'd like to see your party continue to be able to work with the Liberals to keep Parliament going. Is that your view still, that you'd like to see whoever becomes the next prime minister to strike a deal with the NDP to keep Parliament moving?

[Charlie Angus] Since January 6th, the world for Canada's turned upside down. We are in completely uncharted territory. And nobody can say they have a plan to deal with this: none of our Comm's teams; none of our political planners; there's not a politician who's ready to deal with the crisis, because this is the biggest crisis we've seen since the 1930s.

So my simple position as a member of Parliament is to encourage all Parliamentarians to say, "Let's go back to Parliament. Let's see if we can put a plan in place to get Canada through this period. There will be lots of time to to bicker and batter as we love to do. But right now I think my focus is Canada.

Q. On the topic that my colleague just brought up, a little bit of a different focus. Is now perhaps the right time for an early election given the uncertainty surrounding Donald Trump and his administration and the threat of tariffs?

[Charlie Angus] I think what people were thinking on January 1st, and what people saw after January 6th, our world has turned upside down. And we see that Mr. Trump is continuing to attack and menace not just Canada, but the international order. I'm just one Parliamentarian, and I'm ready to go back to Parliament and make it work. I'm willing to do whatever I have to to try and put a plan in place to help Canada get through this. Maybe there will be an election, maybe there won't, but I think we all have an obligation right now to try to reassure Canadians that we are there for them, and that we will do our job to get through what is unprecedented turbulence....'

My focus right now is what do we do to go back to Parliament and try and get a plan for Canadians? That is where we have to stay focused right now.

I think we have to go back and say, "What is it going to mean to work as a Parliament to put in place, the measures at the federal level to withstand the threat, not just economic threats, but the threats to the international order; the threats that we're seeing to NATO; the threats to our sovereignty? There's so many things that we could be doing. But to do that we all have to agree that right now Canada's primary focus needs to be Canada.

Q. So the Trump tariff threats kind of spark some conversations that a lot of our oil is flowing north to south rather than east-west, and to ports, I guess, and it's exposed a weakness in Canadian energy. Some complain that NDP standards stood in the way of these pipelines, as well as some First Nations. What you think about that. Would you be willing to work more to get some of these projects going forward?

[Charlie Angus] Well, it's amazing, you know -- never give up a good opportunity to burn the planet when there's a crisis. Canadians paid $34 billion dollars to build a pipeline. Canadians are subsidizing over 50 cents on every dollar for the pipeline. To be told that Canada hasn't done its share? Why aren't we talking about the huge opportunities to reinvest across the board with energy? The idea that we're going to spend 15 years building a pipeline to oppose Pump-Trump, when we've just built a pipeline, I'd like to see what the oil sector is going to do. They're making record profits, and I haven't seen them offer to do anything yet, except we've seen Madame Smith say that any efforts to have oil and the energy sector play their part, is some kind of threat to Canada.

So this is all speculation. But there's huge things that we could do across our regions that we'd get bigger bang for the bucks. So if they want to post trial balloons, go ahead. But I think there's many opportunities we can have to make a resilient economy right now in the short term.

[Hostess] Thank you. This concludes the press conference.

[Charlie Angus] Thank you.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 39937

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Anti-Anti-Nazi Barbarian Hordes are Knocking Down the Ga

Jamie Raskin Talks About Silicon Valleys' Techno-Libertarian Fascists

by Brian Tyler Cohen

Feb 15, 2025 Interviews with Brian Tyler Cohen

INTERVIEW - Brian interviews Rep. Jamie Raskin about Elon profiting off the federal government while simultaneously slashing programs for working class Americans.

Transcript @6:40

[Jamie Raskin] We need to be supporting the lawyers and the people who are willing to take Trump to court, because we are winning. And that's going to be a really important part of filling that gap you talk about between what the rule of law says, and then what's actually happening. Because we're dealing with a band of incorrigible, lawless plutocrats who think that they can just control the whole U.S. government. And I keep thinking about what Steve Bannon said about Elon Musk. He said he's a truly evil individual. He knows that whole crowd, so he knows what he's talking about. And so that's quite a statement. But in the Silicon Valley network of right-wing, billionaire, libertarian-turned-authoritarians, they are very open about the fact that they think that democracy is obsolete, we're living in a post-Constitutional America, and the Constitution no longer fits. And they are trying to get everybody ready for a Techno-State Monarchy. And in their writings about it, they suggest that seizure of the control of technology, and computers, and financial payments, is the essence to moving from one form of government to another.

So we're really talking about people who would like to abolish American Constitutional institutions, and representative democracy, and the rights and freedom of the people.

Their guy, Curtis Yarvin, who's their big intellectual hero, has said people have got to overcome their fear of the word "Dictator." He says a Dictator is basically just like a corporate CEO, who are all Dictators in their businesses.

And so we need a Dictator that is the corporation, that's the United States of America. And obviously they have Elon Musk in mind, because he could never run for President, he wasn't born in the United States of America, and he's had citizenship in three different countries. He was actually an undocumented immigrant here for many months before he got work authorization, for all the right-wingers out there who want to kick all the undocumented people out of the country, although that might be an argument in their favor. I don't know. But in any event, these people are talking about supplanting our system of Constitutional democracy with a completely different kind of government controlled by Dictatorship.

******************

Curtis Yarvin

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/16/25

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtis_Yarvin

Yarvin in 2023

Born: 1973 (age 51–52)

Nationality: American

Other names: Mencius Moldbug

Education: Brown University (BA); University of California, Berkeley

Spouse(s): Jennifer Kollmer (died 2021); Kristine Militello (2024–)

School: Neo-monarchism; Neo-reactionism; Dark Enlightenment; Anti-egalitarianism; Anti-democracy; Anti-liberalism; Neocameralism; Technofeudalism

Website: Unqualified Reservations – his old blog; Gray Mirror – his new blog

Part of a series on Anarcho-capitalism

People

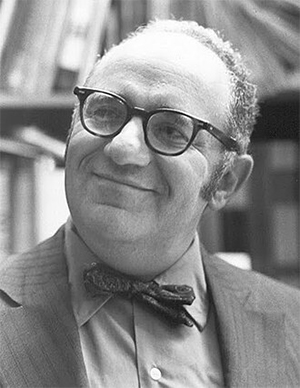

Bruce L. Benson; Walter Block; Bryan Caplan; Gerard Casey; Anthony de Jasay; David D. Friedman; Hans-Hermann Hoppe; Michael Huemer; Stephan Kinsella; Nick Land; Michael Malice; Javier Milei; Robert P. Murphy; Wendy McElroy; Lew Rockwell; Murray Rothbard; Joseph Salerno; Jeffrey Tucker; Tom Woods; Curtis Yarvin

Curtis Guy Yarvin (born 1973), also known by the pen name Mencius Moldbug, is an American blogger. He is known, along with philosopher Nick Land, for founding the anti-egalitarian and anti-democratic philosophical movement known as the Dark Enlightenment or neo-reactionary movement (NRx).[1][2][3][4]

In his blog Unqualified Reservations, which he wrote from 2007 to 2014, and in his later newsletter Gray Mirror, which he started in 2020, he argues that American democracy is a failed experiment[5] that should be replaced by an accountable monarchy, similar to the governance structure of corporations.[6] In 2002, Yarvin began work on a personal software project that eventually became the Urbit networked computing platform. In 2013, he co-founded the company Tlon to oversee the Urbit project and helped lead it until 2019.[7]

Yarvin has been described as a "neo-reactionary", "neo-monarchist" and "neo-feudalist" who "sees liberalism as creating a Matrix-like totalitarian system, and who wants to replace American democracy with a sort of techno-monarchy".[8][9][10][11] He has defended the institution of slavery, and has suggested that certain races may be more naturally inclined toward servitude than others.[12][13] He has claimed that whites have higher IQs than black people, but does not consider himself a white nationalist. He is a critic of US civil rights programs, and has called the civil rights movement a "black-rage industry".[14]

Yarvin has influenced some prominent Silicon Valley investors and Republican politicians, with venture capitalist Peter Thiel described as his "most important connection".[15] Political strategist Steve Bannon has read and admired his work.[16] U.S. Vice President JD Vance has cited Yarvin as an influence.[17][18][19] Michael Anton, the State Department Director of Policy Planning during Trump's second presidency, has also discussed Yarvin's ideas.[20] In January 2025, Yarvin attended a Trump inaugural gala in Washington; Politico reported he was "an informal guest of honor" due to his "outsize influence over the Trumpian right."[21]

Biography

Early life and education

Curtis Guy Yarvin[22] was born in 1973 to a liberal, secular family.[23] His grandparents on his father's side were Jewish American and communists. His father, Herbert Yarvin, worked for the US government as a diplomat,[24] and his mother was a Protestant from Westchester County.[25] In 1985, he entered Johns Hopkins' longitudinal Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth. In 1988, Yarvin graduated from Wilde Lake High School,[26] a public high school in the planned community of Columbia, Maryland.

He attended Brown University from 1988 to 1992, then was a graduate student in a computer science PhD program at UC Berkeley before dropping out after a year and a half to join a tech company.[27][25] During the 1990s, Yarvin was influenced by the libertarian tech culture of Silicon Valley.[27] Yarvin read right-wing and American conservative works. The libertarian University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds introduced him to writers like Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard. The rejection of empiricism by Mises and the Austrian School, who favored instead deduction from first principles, influenced Yarvin's mindset.[28]

Yarvin's pen name, Mencius Moldbug, is a combination of the Confucian philosopher "Mencius" and a play on "goldbug."[24]

Urbit

In 2002, Yarvin founded the Urbit computer platform as a decentralized network of personal servers. In 2013, he co-founded the San Francisco-based company Tlön Corp to build out Urbit further with funding from Peter Thiel's venture capital arm, the Founders Fund.[29][30] In 2016, Yarvin was invited to present on the functional programming aspects of Urbit at LambdaConf 2016, which resulted in the withdrawal of five speakers, two sub-conferences, and several sponsors.[31][32] Yarvin left Tlön in January 2019, but retains some intellectual and financial involvement in the development of Urbit.[7]

Neo-reactionary blogging

Yarvin's reading of Thomas Carlyle convinced him that libertarianism was a doomed project without the inclusion of authoritarianism, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe's 2001 book "Democracy: The God That Failed," marked Yarvin's first break with democracy. Another influence was James Burnham, who asserted that real politics occurred through the actions of elites, beneath what he called apparent democratic or socialist rhetoric.[33] In the 2000s, the failures of US-led nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan strengthened Yarvin's anti-democratic views, the federal response to the 2008 financial crisis strengthened his libertarian convictions, and Barack Obama's election as US president later that year reinforced his belief that history inevitably progresses toward left-leaning societies.[34]

In 2007, Yarvin began the blog Unqualified Reservations to promote his political vision.[35] In an early blog post, he adapted a phrase from the movie The Matrix, repurposing "red pill" to mean a shattering of progressive illusions.[25] He largely stopped updating his blog in 2013, when he began to focus on Urbit; in April 2016, he announced that Unqualified Reservations had "completed its mission".[36]

In 2020, Yarvin began blogging his views on under the page name Gray Mirror.[18] His posts, such as "Reflections on the late election" (2020) and "The butterfly revolution" (2022), are thought experiments on how to achieve an American coup and replace democracy with a new form of monarchy, ideas that critics have described as "fascist".[37]

In January 2025, Yarvin attended a Trump inaugural gala in Washington, D.C., hosted by the far-right publishing house Passage Press; Politico reported he was "an informal guest of honor" due to his "outsize[d] influence over the Trumpian right."[38]

Views

Dark Enlightenment

Main article: Dark Enlightenment

Yarvin believes that real political power in the United States is held by something he calls "the Cathedral", an informal amalgam of universities and the mainstream press, which collude to sway public opinion.[39] According to him, a so-called "Brahmin" social class (in reference to the Brahmin class of India's caste system and the American Boston Brahmin) dominates American society, preaching progressive values to the masses. The socio-religious analogy originates from Yarvin's opinion that the progressive ideology of the Cathedral is delivered to and internalized by the general populace much in the same way religious authorities and institutions deliver religious dogma to fanatical worshippers. Yarvin and the Dark Enlightenment (sometimes abbreviated to "NRx") movement assert that the Cathedral's commitment to equality and justice erodes social order.[40] He advocates an American 'monarch' dissolving elite academic institutions and media outlets within the first few months of their reign.[37]

Drawing on computer metaphors, Yarvin contends that society needs a "hard reset" or a "rebooting", not a series of gradual political reforms.[41] Instead of activism, he advocates passivism, claiming that progressivism would fail without right-wing opposition.[42] According to him, NRx adherents should rather design "new architectures of exit" than engage in ineffective political activism.[43]

Yarvin argues for a "neo-cameralist" philosophy based on Frederick the Great of Prussia's cameralism.[44] In Yarvin's view, democratic governments are inefficient and wasteful and should be replaced with sovereign joint-stock corporations whose "shareholders" (large owners) elect an executive with total power, but who must serve at their pleasure.[41] The executive, unencumbered by liberal-democratic procedures, could rule efficiently much like a CEO-monarch.[41] Yarvin admires Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping for his pragmatic and market-oriented authoritarianism, and the city-state of Singapore as an example of a successful authoritarian regime. He sees the U.S. as soft on crime, dominated by economic and democratic delusions.[40]

Yarvin supports authoritarianism on right-libertarian grounds, claiming that the division of political sovereignty expands the scope of the state, whereas strong governments with clear hierarchies remain minimal and narrowly focused.[40] According to scholar Joshua Tait, "Moldbug imagines a radical libertarian utopia with maximum freedom in all things except politics."[45] He has favored same-sex marriage, freedom of religion, and private use of drugs, and has written against race- or gender-based discriminatory laws, although, according to Tait, "he self-consciously proposed private welfare and prison reforms that resembled slavery".[41] Tait describes Yarvin's writing as contradictory, saying: "He advocates hierarchy, yet deeply resents cultural elites. His political vision is futuristic and libertarian, yet expressed in the language of monarchy and reaction. He is irreligious and socially liberal on many issues but angrily anti-progressive. He presents himself as a thinker searching for truth but admits to lying to his readers, saturating his arguments with jokes and irony. These tensions indicate broader fissures among the online Right."[27]

Under his Moldbug pseudonym, Yarvin gave a talk about "rebooting" the American government at the 2012 BIL Conference. He used it to advocate the acronym "RAGE", which he defined as "Retire All Government Employees". He described what he felt were flaws in the accepted "World War II mythology", alluding to the idea that Hitler's invasions were acts of self-defense. He argued these discrepancies were pushed by America's "ruling communists", who invented political correctness as an "extremely elaborate mechanism for persecuting racists and fascists". "If Americans want to change their government," he said, "they're going to have to get over their dictator phobia."[46]

In the inaugural article published on Unqualified Reservations in 2007, entitled a formalist manifesto, Yarvin called his concept of aligning property rights with political power "formalism", that is, the formal recognition of realities of the existing power, which should eventually be replaced in his views by a new ideology that rejects progressive doctrines transmitted by the Cathedral.[45][47] Yarvin's first use of the term "neoreactionary" to describe his project occurred in 2008.[48][49] His ideas have also been described by Dylan Matthews of Vox as "neo-monarchist".[9]

Yarvin's ideas have been influential among right-libertarians and paleolibertarians, and the public discourses of prominent investors like Peter Thiel have echoed Yarvin's project of seceding from the United States to establish tech-CEO dictatorships.[50][15] Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, an informal adviser to Donald Trump, has spoken approvingly of Yarvin's thinking.[51] Political strategist Steve Bannon has read and admired his work.[16] Vice-president JD Vance has cited Yarvin as an influence, saying in 2021, "So there's this guy Curtis Yarvin who has written about these things," which included "Retire All Government Employees," or RAGE, written in 2012. Vance said that if Trump became president again, "I think what Trump should do, if I was giving him one piece of advice: Fire every single midlevel bureaucrat, every civil servant in the administrative state, and replace them with our people. And when the courts stop you, stand before the country and say, 'The chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it.'"[17][52]

Yarvin suggested in a January 2025 New York Times interview that there was historical precedent to support his reasoning, asserting that in his first inaugural address FDR "essentially says, Hey, Congress, give me absolute power, or I'll take it anyway. So did FDR actually take that level of power? Yeah, he did." The interviewer, David Marchese, remarked that "Yarvin relies on what those sympathetic to his views might see as a helpful serving of historical references — and what others see as a highly distorting mix of gross oversimplification, cherry-picking and personal interpretation presented as fact."[51]

According to Tait, "Moldbug's relationship with the investor-entrepreneur Thiel is his most important connection."[15] Thiel was an investor in Yarvin's startup Tlon and gave $100,000 to Tlon's co-founder John Burnham in 2011.[53][15] In 2016, Yarvin privately asserted to Milo Yiannopoulos that he had been "coaching Thiel" and that he had watched the 2016 US election at Thiel's house.[54] In his writings, Yarvin has pointed to [u]a 2009 essay by Thiel, in which the latter declared: "I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible... Since 1920, the vast increase in welfare beneficiaries and the extension of the franchise to women—two constituencies that are notoriously tough for libertarians—have rendered the notion of 'capitalist democracy' into an oxymoron."[/u][55]

Investor Balaji Srinivasan has also echoed Yarvin's ideas of techno-corporate cameralism. He advocated in a 2013 speech a "society run by Silicon Valley [...] an opt-in society, ultimately outside the US, run by technology."[56][15]

Alt-right

Yarvin has been described as part of the alt-right by journalists and commentators.[44][57][10] Journalist Mike Wendling has called Yarvin "the alt-right's favorite philosophy instructor".[58][44] Tait describes Unqualified Reservations as a "'highbrow' predecessor and later companion to the transgressive anti-'politically correct' metapolitics of nebulous online communities like 4chan and /pol/."[15] Yarvin has publicly distanced himself from the alt-right. In a private message, Yarvin counseled Milo Yiannopoulos, then a reporter at Breitbart News, to deal with neo-Nazis "the way some perfectly tailored high-communist NYT reporter handles a herd of greasy anarchist hippies. Patronizing contempt. Your heart is in the right place, young lady, now get a shower and shave those pits."[59]

Writing in Vanity Fair, James Pogue said of Yarvin:

In Commonweal, Matt McManus said of Yarvin:

Yarvin came to public attention in February 2017 when Politico magazine reported that Steve Bannon, who served as White House Chief Strategist under U.S. President Donald Trump, read Yarvin's blog and that Yarvin "has reportedly opened up a line to the White House, communicating with Bannon and his aides through an intermediary."[62] The story was picked up by other magazines and newspapers, including The Atlantic, The Independent, and Mother Jones.[44][63][64] Yarvin denied to Vox that he was in contact with Bannon in any way,[9] but he jokingly told The Atlantic that his White House contact was the Twitter user Bronze Age Pervert.[44] Yarvin later gave a copy of Bronze Age Pervert's book Bronze Age Mindset to Michael Anton, a former senior national security official in the first Trump administration. Trump also named Anton to be the U.S. State Department Director of Policy Planning in his second presidency.[65][66][67]

In a May 2021 conversation, Anton said Yarvin was arguing that a president could "gain power lawfully through an election, and then exercise it unlawfully." Yarvin replied, "It wouldn't be unlawful. You'd simply declare a state of emergency in your inaugural address," adding, "you'd actually have a mandate to do this. Where would that mandate come from? It would come from basically running on it, saying, 'Hey, this is what we're going to do.'" He continued that if a hypothetical authoritarian president were to take office in January 2025, "you can't continue to have a Harvard or a New York Times past since perhaps the start of April" because "the idea that you're going to be a Caesar and take power and operate with someone else's Department of Reality in operation is just manifestly absurd. Machiavelli could tell you right away that that's a stupid idea."[20]

Views on race

Yarvin has alleged that whites have higher IQs than blacks for genetic reasons. He has been described as a modern-day supporter of slavery, a description he disputes.[68][31] He has claimed that some races are more suited to slavery than others.[31] In a post that linked approvingly to Steve Sailer and Jared Taylor, he wrote: "It should be obvious that, although I am not a white nationalist, I am not exactly allergic to the stuff. [Anti-anti-White Nationalist]"[44][69] In 2009, he wrote that since US civil rights programs were "applied to populations with recent hunter-gatherer ancestry and no great reputation for sturdy moral fiber", the result was "absolute human garbage."[70]

Yarvin disputes accusations of racism,[68] and in his essays, "Why I am not a White Nationalist" and "Why I am not an Anti-Semite," he offered a somewhat sympathetic analysis of those ideologies before ultimately rejecting them.[25] He has also described the use of IQ tests to determine superiority as "creepy".[31]

Personal life

Yarvin was married to Jennifer Kollmer, who died in 2021 and with whom he had two children.[71] He was briefly engaged to writer Lydia Laurenson, with whom he has one child.[60][72][73] He married Kristine Militello in 2024.[74]

He is an atheist.[24]

See also

• Anarchocapitalism

• Authoritarian capitalism

• Counter-Enlightenment

• Criticism of democracy

• Dark Enlightenment

• Far-right politics

• Fusionism

• Natural order

• Neo-feudalism

• Paleoconservatism

• Paleolibertarianism

• Radical right

• Reactionary

• Reactionary modernism

References

1. Tait 2019, p. 188: "He became the founding theorist of the 'neoreactionary' movement, an online collection of writers determined to theorize a superior alternative to democracy. ... Sometimes called the 'Reactionary Enlightenment', neoreaction is an alchemy of authoritarian and libertarian thought."

2. Smith & Burrows 2021, p. 145: "There are numerous individuals associated with NRx ideas, but four are perhaps key: two – Curtis Yarvin and Nick Land – might be considered the original 'builders' ... of the position."; p. 148: "Yarvin is probably the most important figure in NRx, as it would be fair to regard his UR blog as the foundational text of the movement ... Originally called 'neocameralism', his position soon became known as 'neoreactionary' philosophy (NRx) and then, once passed through Land's nihilist Deleuzian filter, as The Dark Enlightenment."

3. Kindinger, Evangelia; Schmitt, Mark (January 4, 2019). "Conclusion: Digital culture and the afterlife of white supremacist movements". The Intersections of Whiteness. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-11277-2. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

4. Gray, Rosie (February 10, 2017). "The Anti-Democracy Movement Influencing the Right". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

5. Matthews, Dylan (April 18, 2016). "The alt-right is more than warmed-over white supremacy. It's that, but way way weirder". Vox. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

6. Hawley, George (2017). Making sense of the alt-right. Columbia University Press. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-0231185127.

7. Smith & Burrows 2021, p. 152.

8. Goldberg, Michelle (April 26, 2022). "Opinion | The Awful Advent of Reactionary Chic". The New York Times.

9. Matthews, Dylan (February 7, 2017). "Neo-monarchist blogger denies he's chatting with Steve Bannon". Vox. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

10. Lecher, Colin (February 21, 2017). "Alt-right darling Mencius Moldbug wanted to destroy democracy. Now he wants to sell you web services". The Verge. Archived from the original on June 13, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

11. "The Moldbug Variations | Corey Pein". The Baffler. October 9, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2025.

12. Lehmann, Chris (October 27, 2022). "The Reactionary Prophet of Silicon Valley". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved February 14, 2025.

13. Townsend, Tess (March 31, 2016). "Controversy Rages Over 'Pro-Slavery' Tech Speaker Curtis Yarvin". Inc. Archived from the original on January 28, 2025. Retrieved February 14, 2025.

14. "Chapter 3: AGW, KFM, and HNU | A Gentle Introduction to Unqualified Reservations | Unqualified Reservations by Mencius Moldbug". http://www.unqualified-reservations.org. Retrieved February 14, 2025.

15. Tait 2019, p. 200.

16. Tait 2019, p. 199.

17. Mahler, Jonathan; Mac, Ryan; Schleifer, Theodore (October 18, 2024). "How Tech Billionaires Became the G.O.P.'s New Donor Class". The New York Times.

18. "Curtis Yarvin wants American democracy toppled. He has some prominent Republican fans". October 24, 2022.

19. Ward, Ian (October 24, 2022). "The Seven Thinkers and Groups That Have Shaped JD Vance's Unusual Worldview". Politico.

20. WIlson, Jason (December 21, 2024). "He's anti-democracy and pro-Trump: the obscure 'dark enlightenment' blogger influencing the next US administration". The Guardian.

21. Ian, Ward (January 30, 2025). "Curtis Yarvin's Ideas Were Fringe. Now They're Coursing Through Trump's Washington". Politico.

22. Pein 2018, p. 211.

23. Tait 2019, pp. 189–190.

24. "Interview with Curtis Yarvin". Interviews with Max Raskin. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

25. Siegel 2022.

26. Yarvin, Curtis (October 26, 2011). "The Holocaust: A Nazi Perspective". Unqualified Reservations/MenciusMoldbug. Retrieved January 19, 2025.

27. Tait 2019, p. 189.

28. Tait 2019, p. 190.

29. Smith & Burrows 2021, pp. 152–153.

30. Pein, Corey (October 9, 2017) [October 9, 2017]. "The Moldbug Variations | Corey Pein". The Baffler. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024. Retrieved August 27, 2024.

31. Townsend, Tess (March 31, 2016). "Controversy Rages Over 'Pro-Slavery' Tech Speaker Curtis Yarvin". Inc.com. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2016. Yarvin's online writings, many under his pseudonym Mencius Moldbug, convey blatantly racist views. He expresses the belief that white people are genetically endowed with higher IQs than black people. He has suggested race may determine whether individuals are better suited for slavery, and his writing has been interpreted as supportive of the institution of slavery. ... Yarvin disputes that he agrees with the institution of slavery, but many interpret his writings as screeds supportive of bondage of black people. He writes in an email to Inc., 'I don't know if we can say *biologically* that part of the genius of the African-American people is the talent they showed in enduring slavery. But this is certainly true in a cultural and literary sense. In any case, it is easiest to admire a talent when one lacks it, as I do.' ... In Yarvin's Medium blog post, he wrote that while he disagrees with the concept that 'all races are equally smart,' he is not racist because he rejects what he refers to as 'IQism.'

32. Townsend, Tess (April 5, 2016). "Citing 'Open Society,' Racist Programmer's Allies Raise $20K on Indiegogo". Inc.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

33. Tait 2019, p. 191.

34. Tait 2019, p. 192.

35. Tait 2019, p. 187.

36. Tait 2019, p. 198.

37. Prokop, Andrew (October 24, 2022). "Curtis Yarvin wants American democracy toppled. He has some prominent Republican fans". Vox. Retrieved July 27, 2024. Shut down elite media and academic institutions: Now, recall that, according to Yarvin's theories, true power is held by 'the Cathedral,' so they have to go, too. The new monarch/dictator should order them dissolved. 'You can't continue to have a Harvard or a New York Times past the start of April,' he told Anton. After that, he says, people should be allowed to form new associations and institutions if they want, but the existing Cathedral power bases must be torn down.

38. Ian, Ward (January 30, 2025). "Curtis Yarvin's Ideas Were Fringe. Now They're Coursing Through Trump's Washington". Politico.

39. Sullivan, Andrew (April 2017). "The Reactionary Temptation". New York. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

40. Tait 2019, p. 195.

41. Tait 2019, p. 197.

42. Tait 2019, pp. 197–198.

43. Smith & Burrows 2021, p. 149.

44. Gray, Rosie (February 10, 2017). "Behind the Internet's Anti-Democracy Movement". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

45. Tait 2019, p. 196.

46. Pein 2018, pp. 216–217

47. Smith & Burrows 2021, p. 148

48. Hermansson et al. 2020, p. 65.

49. Moldbug, Mencius (June 19, 2008). "Chapter X: A Simple Sovereign Bankruptcy Procedure | An Open Letter to Open-Minded Progressives". Unqualified Reservations. If I had to choose one word and stick with it, I'd pick "restorationist." If I have to concede one pejorative which fair writers can fairly apply, I'll go with "reactionary." I'll even answer to any compound of the latter—"neoreactionary," "postreactionary," "ultrareactionary," etc.

50. Pein 2018, pp. 228–230.

51. Marchese, David (January 18, 2025). "Curtis Yarvin Says Democracy Is Done. Powerful Conservatives Are Listening". The New York Times.

52. Del Valle, Gaby (October 16, 2024). "JD Vance thinks monarchists have some good ideas". The Verge.

53. Pein 2018, p. 228.

54. Tait 2019, p. 200; Hermansson et al. 2020, pp. 95–96; quoting Bernstein 2017 Archived January 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

55. Smith & Burrows 2021, pp. 148–149; quoting Thiel 2009 Archived April 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

56. Pein 2018, pp. 278–281.

57. Bernstein, Joseph (October 5, 2017). "Here's How Breitbart And Milo Smuggled Nazi and White Nationalist Ideas Into The Mainstream". BuzzFeed News.

58. Wendling, Mike (2018). Alt Right: From 4chan to the White House. Pluto Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-7453-3795-1.

59. Tait 2019, p. 199; quoting Bernstein 2017 Archived January 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

60. Pogue, James (April 20, 2022). "Inside the New Right, Where Peter Thiel Is Placing His Biggest Bets". Vanity Fair.

61. McManus, Matt (January 27, 2023) "Yarvin's Case Against Democracy." Commonweal. (Retrieved January 27, 2023.)

62. Johnson, Eliana; Stokols, Eli (February 2017). "What Steve Bannon Wants You to Read". Politico. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

63. Revesz, Rachael (February 27, 2017). "Steve Bannon 'connects network of white nationalists' at the White House". The Independent. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

64. Levy, Pema (March 26, 2017). "Stephen Bannon Is a Fan of a French Philosopher...Who Was an Anti-Semite and a Nazi Supporter". Mother Jones. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

65. Anton, Michael (August 14, 2019). "Are the Kids Al(t)right?". Claremont Review of Books. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

66. Schreckinger, Ben (August 23, 2019). "The alt-right manifesto that has Trumpworld talking". Politico. Archived from the original on August 26, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

67. Irwin, Lauren (December 8, 2024). "Trump names several picks for State Department roles". The Hill.

68. Byars, Mitchell (April 6, 2016). "Speaker Curtis Yarvin's racial views bring controversy to Boulder conference". Daily Camera: Boulder News. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved June 30, 2016. A programming conference in Boulder this May has become surrounded by controversy after organizers decided to let Curtis Yarvin — a programmer who has blogged under the pseudonym Mencius Moldbug about his views that white people are genetically smarter than black people — remain a speaker at the event. ... But Yarvin's views, which some have alleged are racist and endorse the institution of slavery, already have led to him being kicked out of a conference in 2015, and there has been pressure on LambdaConf to do the same. ... 'I am not an "outspoken advocate for slavery," a racist, a sexist or a fascist,' he wrote. 'I don't equate anatomical traits (whether sprinting speed or problem-solving efficiency) with moral superiority. ... '

69. Marantz, Andrew (2019). Antisocial: online extremists, techno-utopians, and the hijacking of the American conversation. Penguin. p. 156. ISBN 978-0525522263.

70. Tait 2019, p. 194; quoting Moldbug, 2009 archive.

71. Yarvin, Curtis (April 7, 2021). "Jennifer Kollmer, 1971-2021". Gray Mirror. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

72. "I Am No Longer Engaged To Curtis Yarvin -". archive.ph. September 27, 2022. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

73. Yarvin, Curtis (September 25, 2022). "Podcasts and a personal note". Gray Mirror. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

74. Black, Julia (August 9, 2024). "The Far-Right Guru Who has Befriended Silicon Valley's Extreme Factions". The Information. Retrieved October 1, 2024.

Sources

• Hermansson, Patrik; Lawrence, David; Mulhall, Joe; Murdoch, Simon (2020). The International Alt-Right: Fascism for the 21st Century?. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-62709-5.

• Pein, Corey (2018). Live Work Work Work Die: A Journey into the Savage Heart of Silicon Valley. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-1-62779-486-2.

• Siegel, Jacob (March 31, 2022). "The Red-Pill Prince: How computer programmer Curtis Yarvin became America's most controversial political theorist". Tablet Magazine.

• Smith, Harrison; Burrows, Roger (2021). "Software, Sovereignty and the Post-Neoliberal Politics of Exit". Theory, Culture & Society. 38 (6): 143–166. doi:10.1177/0263276421999439. hdl:1983/9261276b-8184-482c-b184-915655df6c19. ISSN 0263-2764. S2CID 234839947.

• Tait, Joshua (2019). "Mencius Moldbug and Neoreaction". In Sedgwick, Mark (ed.). Key Thinkers of the Radical Right: Behind the New Threat to Liberal Democracy. Oxford University Press. pp. 187–203. ISBN 978-0190877606.

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to Curtis Yarvin.

• Unqualified Reservations – his old blog

• Gray Mirror – his new blog

• Interview with Curtis Yarvin, The New York Times, January 2025

by Brian Tyler Cohen

Feb 15, 2025 Interviews with Brian Tyler Cohen

INTERVIEW - Brian interviews Rep. Jamie Raskin about Elon profiting off the federal government while simultaneously slashing programs for working class Americans.

Transcript @6:40

[Jamie Raskin] We need to be supporting the lawyers and the people who are willing to take Trump to court, because we are winning. And that's going to be a really important part of filling that gap you talk about between what the rule of law says, and then what's actually happening. Because we're dealing with a band of incorrigible, lawless plutocrats who think that they can just control the whole U.S. government. And I keep thinking about what Steve Bannon said about Elon Musk. He said he's a truly evil individual. He knows that whole crowd, so he knows what he's talking about. And so that's quite a statement. But in the Silicon Valley network of right-wing, billionaire, libertarian-turned-authoritarians, they are very open about the fact that they think that democracy is obsolete, we're living in a post-Constitutional America, and the Constitution no longer fits. And they are trying to get everybody ready for a Techno-State Monarchy. And in their writings about it, they suggest that seizure of the control of technology, and computers, and financial payments, is the essence to moving from one form of government to another.

So we're really talking about people who would like to abolish American Constitutional institutions, and representative democracy, and the rights and freedom of the people.

Their guy, Curtis Yarvin, who's their big intellectual hero, has said people have got to overcome their fear of the word "Dictator." He says a Dictator is basically just like a corporate CEO, who are all Dictators in their businesses.

The Corporation as Sovereign

by Allison D. Garrett

Maine Law Review

Volume 60 Number 1 Article 4

January 2008

Abstract

In the past two hundred years, sovereignty devolved from the monarch to the people in many countries; in our lifetimes, it has devolved in several significant ways from the people to the corporation. We are witnesses to the erosion of traditional Westphalian concepts of sovereignty, where the chess game of international politics is played out by nation-states, each governing a certain geographic area and group of people. Eulogies for the nation-state often cite globalization as the cause of death. The causa mortis is characterized by the increase in the power and normative influence of supranational organizations, such as the United Nations, World Bank, European Union, International Monetary Fund, and non-governmental organizations. Today, geography lacks the political significance it once had, as valuable commodities instantly pass over, through, and under geographic borders in the world’s most common language, binary code. Telecommunications, when combined with mobile capital and technology, “is viewed as obliterating spatial lines.” All of these changes have made the nation-state, as a geopolitical entity, far less significant than it has been in the past several decades. Corporations have stepped into this power vacuum with a reach and economic influence so broad that some of the duties of sovereign nations have fallen under their aegis. The power and influence of the world’s major corporations continue to grow, and with this growth their similarities to sovereign states increase. As the nation-state is prematurely eulogized, scholars are writing about the privatization of governance and commerce. Many scholars tend to focus on international relations and the extent to which relationships among nations have been transcended or superseded by private actors. For example, the concept of nations acting as private entities has been recognized in the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, which provides that “a foreign state shall not be immune . . . in any case in which the action is based upon a commercial activity carried on in the United States by a foreign state.” This Article focuses, instead, on how the distinction between corporations and the state is blurring, not only internationally, but also domestically, as corporations act in ways that make them similar to nation-states.

And so we need a Dictator that is the corporation, that's the United States of America. And obviously they have Elon Musk in mind, because he could never run for President, he wasn't born in the United States of America, and he's had citizenship in three different countries. He was actually an undocumented immigrant here for many months before he got work authorization, for all the right-wingers out there who want to kick all the undocumented people out of the country, although that might be an argument in their favor. I don't know. But in any event, these people are talking about supplanting our system of Constitutional democracy with a completely different kind of government controlled by Dictatorship.

******************

Curtis Yarvin

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 2/16/25

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtis_Yarvin

Yarvin in 2023

Born: 1973 (age 51–52)

Nationality: American

Other names: Mencius Moldbug

Education: Brown University (BA); University of California, Berkeley

Spouse(s): Jennifer Kollmer (died 2021); Kristine Militello (2024–)

School: Neo-monarchism; Neo-reactionism; Dark Enlightenment; Anti-egalitarianism; Anti-democracy; Anti-liberalism; Neocameralism; Technofeudalism

Website: Unqualified Reservations – his old blog; Gray Mirror – his new blog

Part of a series on Anarcho-capitalism

People

Bruce L. Benson; Walter Block; Bryan Caplan; Gerard Casey; Anthony de Jasay; David D. Friedman; Hans-Hermann Hoppe; Michael Huemer; Stephan Kinsella; Nick Land; Michael Malice; Javier Milei; Robert P. Murphy; Wendy McElroy; Lew Rockwell; Murray Rothbard; Joseph Salerno; Jeffrey Tucker; Tom Woods; Curtis Yarvin

Curtis Guy Yarvin (born 1973), also known by the pen name Mencius Moldbug, is an American blogger. He is known, along with philosopher Nick Land, for founding the anti-egalitarian and anti-democratic philosophical movement known as the Dark Enlightenment or neo-reactionary movement (NRx).[1][2][3][4]

In his blog Unqualified Reservations, which he wrote from 2007 to 2014, and in his later newsletter Gray Mirror, which he started in 2020, he argues that American democracy is a failed experiment[5] that should be replaced by an accountable monarchy, similar to the governance structure of corporations.[6] In 2002, Yarvin began work on a personal software project that eventually became the Urbit networked computing platform. In 2013, he co-founded the company Tlon to oversee the Urbit project and helped lead it until 2019.[7]

Yarvin has been described as a "neo-reactionary", "neo-monarchist" and "neo-feudalist" who "sees liberalism as creating a Matrix-like totalitarian system, and who wants to replace American democracy with a sort of techno-monarchy".[8][9][10][11] He has defended the institution of slavery, and has suggested that certain races may be more naturally inclined toward servitude than others.[12][13] He has claimed that whites have higher IQs than black people, but does not consider himself a white nationalist. He is a critic of US civil rights programs, and has called the civil rights movement a "black-rage industry".[14]

Yarvin has influenced some prominent Silicon Valley investors and Republican politicians, with venture capitalist Peter Thiel described as his "most important connection".[15] Political strategist Steve Bannon has read and admired his work.[16] U.S. Vice President JD Vance has cited Yarvin as an influence.[17][18][19] Michael Anton, the State Department Director of Policy Planning during Trump's second presidency, has also discussed Yarvin's ideas.[20] In January 2025, Yarvin attended a Trump inaugural gala in Washington; Politico reported he was "an informal guest of honor" due to his "outsize influence over the Trumpian right."[21]

Biography

Early life and education

Curtis Guy Yarvin[22] was born in 1973 to a liberal, secular family.[23] His grandparents on his father's side were Jewish American and communists. His father, Herbert Yarvin, worked for the US government as a diplomat,[24] and his mother was a Protestant from Westchester County.[25] In 1985, he entered Johns Hopkins' longitudinal Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth. In 1988, Yarvin graduated from Wilde Lake High School,[26] a public high school in the planned community of Columbia, Maryland.

He attended Brown University from 1988 to 1992, then was a graduate student in a computer science PhD program at UC Berkeley before dropping out after a year and a half to join a tech company.[27][25] During the 1990s, Yarvin was influenced by the libertarian tech culture of Silicon Valley.[27] Yarvin read right-wing and American conservative works. The libertarian University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds introduced him to writers like Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard. The rejection of empiricism by Mises and the Austrian School, who favored instead deduction from first principles, influenced Yarvin's mindset.[28]

Yarvin's pen name, Mencius Moldbug, is a combination of the Confucian philosopher "Mencius" and a play on "goldbug."[24]

Urbit

In 2002, Yarvin founded the Urbit computer platform as a decentralized network of personal servers. In 2013, he co-founded the San Francisco-based company Tlön Corp to build out Urbit further with funding from Peter Thiel's venture capital arm, the Founders Fund.[29][30] In 2016, Yarvin was invited to present on the functional programming aspects of Urbit at LambdaConf 2016, which resulted in the withdrawal of five speakers, two sub-conferences, and several sponsors.[31][32] Yarvin left Tlön in January 2019, but retains some intellectual and financial involvement in the development of Urbit.[7]

Neo-reactionary blogging

Yarvin's reading of Thomas Carlyle convinced him that libertarianism was a doomed project without the inclusion of authoritarianism, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe's 2001 book "Democracy: The God That Failed," marked Yarvin's first break with democracy. Another influence was James Burnham, who asserted that real politics occurred through the actions of elites, beneath what he called apparent democratic or socialist rhetoric.[33] In the 2000s, the failures of US-led nation-building in Iraq and Afghanistan strengthened Yarvin's anti-democratic views, the federal response to the 2008 financial crisis strengthened his libertarian convictions, and Barack Obama's election as US president later that year reinforced his belief that history inevitably progresses toward left-leaning societies.[34]

In 2007, Yarvin began the blog Unqualified Reservations to promote his political vision.[35] In an early blog post, he adapted a phrase from the movie The Matrix, repurposing "red pill" to mean a shattering of progressive illusions.[25] He largely stopped updating his blog in 2013, when he began to focus on Urbit; in April 2016, he announced that Unqualified Reservations had "completed its mission".[36]

In 2020, Yarvin began blogging his views on under the page name Gray Mirror.[18] His posts, such as "Reflections on the late election" (2020) and "The butterfly revolution" (2022), are thought experiments on how to achieve an American coup and replace democracy with a new form of monarchy, ideas that critics have described as "fascist".[37]

In January 2025, Yarvin attended a Trump inaugural gala in Washington, D.C., hosted by the far-right publishing house Passage Press; Politico reported he was "an informal guest of honor" due to his "outsize[d] influence over the Trumpian right."[38]

Views

Dark Enlightenment

Main article: Dark Enlightenment

Yarvin believes that real political power in the United States is held by something he calls "the Cathedral", an informal amalgam of universities and the mainstream press, which collude to sway public opinion.[39] According to him, a so-called "Brahmin" social class (in reference to the Brahmin class of India's caste system and the American Boston Brahmin) dominates American society, preaching progressive values to the masses. The socio-religious analogy originates from Yarvin's opinion that the progressive ideology of the Cathedral is delivered to and internalized by the general populace much in the same way religious authorities and institutions deliver religious dogma to fanatical worshippers. Yarvin and the Dark Enlightenment (sometimes abbreviated to "NRx") movement assert that the Cathedral's commitment to equality and justice erodes social order.[40] He advocates an American 'monarch' dissolving elite academic institutions and media outlets within the first few months of their reign.[37]

Drawing on computer metaphors, Yarvin contends that society needs a "hard reset" or a "rebooting", not a series of gradual political reforms.[41] Instead of activism, he advocates passivism, claiming that progressivism would fail without right-wing opposition.[42] According to him, NRx adherents should rather design "new architectures of exit" than engage in ineffective political activism.[43]

Yarvin argues for a "neo-cameralist" philosophy based on Frederick the Great of Prussia's cameralism.[44] In Yarvin's view, democratic governments are inefficient and wasteful and should be replaced with sovereign joint-stock corporations whose "shareholders" (large owners) elect an executive with total power, but who must serve at their pleasure.[41] The executive, unencumbered by liberal-democratic procedures, could rule efficiently much like a CEO-monarch.[41] Yarvin admires Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping for his pragmatic and market-oriented authoritarianism, and the city-state of Singapore as an example of a successful authoritarian regime. He sees the U.S. as soft on crime, dominated by economic and democratic delusions.[40]

Yarvin supports authoritarianism on right-libertarian grounds, claiming that the division of political sovereignty expands the scope of the state, whereas strong governments with clear hierarchies remain minimal and narrowly focused.[40] According to scholar Joshua Tait, "Moldbug imagines a radical libertarian utopia with maximum freedom in all things except politics."[45] He has favored same-sex marriage, freedom of religion, and private use of drugs, and has written against race- or gender-based discriminatory laws, although, according to Tait, "he self-consciously proposed private welfare and prison reforms that resembled slavery".[41] Tait describes Yarvin's writing as contradictory, saying: "He advocates hierarchy, yet deeply resents cultural elites. His political vision is futuristic and libertarian, yet expressed in the language of monarchy and reaction. He is irreligious and socially liberal on many issues but angrily anti-progressive. He presents himself as a thinker searching for truth but admits to lying to his readers, saturating his arguments with jokes and irony. These tensions indicate broader fissures among the online Right."[27]

Under his Moldbug pseudonym, Yarvin gave a talk about "rebooting" the American government at the 2012 BIL Conference. He used it to advocate the acronym "RAGE", which he defined as "Retire All Government Employees". He described what he felt were flaws in the accepted "World War II mythology", alluding to the idea that Hitler's invasions were acts of self-defense. He argued these discrepancies were pushed by America's "ruling communists", who invented political correctness as an "extremely elaborate mechanism for persecuting racists and fascists". "If Americans want to change their government," he said, "they're going to have to get over their dictator phobia."[46]

In the inaugural article published on Unqualified Reservations in 2007, entitled a formalist manifesto, Yarvin called his concept of aligning property rights with political power "formalism", that is, the formal recognition of realities of the existing power, which should eventually be replaced in his views by a new ideology that rejects progressive doctrines transmitted by the Cathedral.[45][47] Yarvin's first use of the term "neoreactionary" to describe his project occurred in 2008.[48][49] His ideas have also been described by Dylan Matthews of Vox as "neo-monarchist".[9]