Part 1 of 2

Brief of the United States

Donald J. Trump v. United States of America, No. 22-13005 No. 22-13005

October 14, 2022

Donald J. Trump v. United States of America, No. 22-13005

No. 22-13005

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

DONALD J. TRUMP,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Defendant-Appellant.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Florida

BRIEF OF THE UNITED STATES

JUAN ANTONIO GONZALEZ

United States Attorney

Southern District of Florida

99 NE 4th Street, 8th Floor

Miami, FL 33132

305-961-9001

MATTHEW G. OLSEN

Assistant Attorney General

JAY I. BRATT

Chief, Counterintelligence and Export

Control Section

JULIE EDELSTEIN

SOPHIA BRILL

JEFFREY M. SMITH

Attorneys

National Security Division

U.S. Department of Justice

950 Pennsylvania Ave., NW

Washington, DC 20530

202-233-0986

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 26.1 and Eleventh Circuit Rules 26.1-1 and 28-1(b), the undersigned hereby certifies that the following have an interest in the outcome of this case:

American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. (DIS)

Associated Press

Bloomberg, LP

Bratt, Jay I.

Brill, Sophia

Cable News Network, Inc. (WBD)

Cannon, Hon. Aileen M.

Caramanica, Mark Richard

CBS Broadcasting, Inc (CBS)

Corcoran, M. Evan

Cornish, Sr., O’Rane M.

Dearie, Hon. Raymond J.

Dow Jones & Company, Inc. (DJI)

Edelstein, Julie

Eisen, Norman Larry

E.W. Scripps Company (SSP)

Finzi, Roberto

Fischman, Harris

Former Federal and State Government Officials

Fugate, Rachel Elise

Gonzalez, Juan Antonio

Gray Media Group, Inc. (GTN)

Gupta, Angela D.

Halligan, Lindsey

Inman, Joseph M.

Karp, Brad S.

Kessler, David K.

Kise, Christopher M.

Knopf, Andrew Franklin

Lacosta, Anthony W.

LoCicero, Carol Jean

McElroy, Dana Jane

Minchin, Eugene Branch

NBC Universal Media, LLC (CMCSA)

Patel, Raj K.

Rakita, Philip

Reeder, Jr., L. Martin

Reinhart, Hon. Bruce E.

Rosenberg, Robert

Seidlin-Bernstein, Elizabeth

Shapiro, Jay B.

Shullman, Deanna Kendall

Smith, Jeffrey M.

The New York Times Company (NYT)

The Palm Beach Post

Times Publishing Company

Tobin, Charles David

Trump, Donald J.

Trusty, James M.

United States of America

Wertheimer, Fred

WP Company, LLC

Dated: October 14, 2022 /s/ Sophia Brill

Sophia Brill

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

The government respectfully submits that oral argument would assist the Court. In its October 5, 2022 order granting the government’s motion to expedite this appeal, the Court indicated that “the appeal will be assigned to a special merits panel,” which “will decide when and how to hear oral argument.”

TABLE OF CONTENTS

• CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS AND CORPORATE

• DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ..................................................................................... c-1

• STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT ................................................ i

• TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................... iv

• INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1

• STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ............................................................................ 4

• STATEMENT OF ISSUES .............................................................................................. 4

• STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...................................................................................... 5

• A. Factual Background ................................................................................................. 5

• B. Procedural History .................................................................................................. 10

• 1. Initiation of Plaintiff’s suit..................................................................................... 10

• 2. The district court’s order and stay proceedings .................................................. 12

• 3. The special master proceedings ............................................................................ 16

• 4. Other appellate proceedings ................................................................................. 17

• C. Standards of Review ............................................................................................... 17

• SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...................................................................................... 18

• ARGUMENT...................................................................................................................... 20

• I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN EXERCISING EQUITABLE

JURISDICTION ................................................................................................................ 20

• A. Plaintiff Failed to Establish the “Foremost” Factor Needed for the

Exercise of Jurisdiction ................................................................................................. 22

• B. The Remaining Richey Factors Weigh Further Against the Exercise of

Jurisdiction ....................................................................................................................... 23

• II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED BY ENJOINING THE

GOVERNMENT FROM REVIEWING OR USING THE SEIZED

RECORDS ........................................................................................................................... 28

• A. Plaintiff Has No Plausible Claims of Executive Privilege ........................... 29

• 1. Plaintiff cannot invoke executive privilege to bar the Executive Branch’s

review and use of its own records ................................................................................ 29

• 2. United States v. Nixon forecloses any executive privilege claims ........................ 31

• 3. Any claim of executive privilege as to the records bearing classification

markings would fail for additional reasons ................................................................. 36

• B. Plaintiff Has No Plausible Claims of Attorney-Client Privilege That

Would Justify an Injunction ......................................................................................... 38

• C. The Government and the Public Suffer Irreparable Injury from the

Injunction Pending the Special-Master Review ..................................................... 40

• D. Plaintiff’s Purported Factual Disputes Are Irrelevant ................................... 43

• 1. Plaintiff’s suggestion that he might have declassified the seized records is

irrelevant .......................................................................................................................... 43

• 2. Plaintiff’s suggestion that he might have categorized seized records as

“personal” records under the PRA only weakens his executive privilege claims .. 45

• III. THE COURT SHOULD REVERSE THE DISTRICT COURT’S

REQUIREMENT THAT THE GOVERNMENT SUBMIT THE RECORDS

FOR A SPECIAL-MASTER REVIEW ....................................................................... 47

• CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................. 51

• CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE .......................................................................... 52

• CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ..................................................................................... 53

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page:

• Al Odah v. United States,

• 559 F.3d 539 (D.C. Cir. 2009).......................................................................................... 50

• Bonner v. City of Prichard,

• 661 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir. 1981) ........................................................................................ 13

• BP P.L.C. v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,

• 141 S. Ct. 1532 (2021) ....................................................................................................... 50

• CIA v. Sims,

• 471 U.S. 159 (1985) ........................................................................................................... 37

• Cobbledick v. United States,

• 309 U.S. 323 (1940) ...................................................................................................... 41-42

• Cooter & Gell v. Hartmarx Corp.,

• 496 U.S. 384 (1990) ........................................................................................................... 18

• Deaver v. Seymour,

• 822 F.2d 66 (D.C. Cir. 1987) ............................................................................................ 26

• Dep’t of Navy v. Egan,

• 484 U.S. 518 (1988) ..................................................................................................... 31, 37

• Douglas v. City of Jeanette,

• 319 U.S. 157 (1943) ........................................................................................................... 21

• Hunsucker v. Phinney,

• 497 F.2d 29 (5th Cir. 1974) .................................................................................. 13, passim

• In re Grand Jury Subpoenas,

• 454 F.3d 511 (6th Cir. 2006) ............................................................................................ 25

• In re Sealed Case,

• 121 F.3d 729 (D.C. Cir. 1997).......................................................................................... 32

• In re Sealed Search Warrant,

• No. 20-MJ-3278, 2020 WL 6689045 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 2, 2020) aff’d,

• 11 F.4th 1235 (11th Cir. 2021) ......................................................................................... 25

• In re Search of 4801 Fyler Ave.,

• 879 F.2d 385 (8th Cir. 1989) ...................................................................................... 22, 23

• In re Search Warrant Issued June 13, 2019,

• 942 F.3d 159 (4th Cir. 2019) ............................................................................................ 48

• In re Wild,

• 994 F.3d 1244 (11th Cir. 2021) ........................................................................................ 42

• Jones v. Fransen,

• 857 F.3d 843 (11th Cir. 2017) .......................................................................................... 49

• Judicial Watch v. NARA,

• 845 F. Supp. 2d 288 (D.D.C. 2012) ................................................................................ 46

• Keystone Driller Co. v. General Excavator Co.,

• 290 U.S. 240 (1933) ........................................................................................................... 38

• Mohawk Industries, Inc. v. Carpenter,

• 558 U.S. 100 (2009) ........................................................................................................... 50

• Munaf v. Geren,

• 553 U.S. 674 (2008) ........................................................................................................... 27

• Murphy v. Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t of Army,

• 769 F. App’x. 779 (11th Cir. 2019) .................................................................................. 37

• *Nixon v. Administrator of General Services,

• 433 U.S. 425 (1977) ................................................................................................. 3, passim

• Ramirez v. Collier,

• 142 S. Ct. 1264 (2022) ....................................................................................................... 38

• Ramsden v. United States,

• 2 F.3d 322 (9th Cir. 1993) .......................................................................................... 24, 26

• *Richey v. Smith,

• 515 F.2d 1239 (5th Cir. 1975) .............................................................................. 13, passim

• Snepp v. United States States,

• 544 U.S. 507 (1980) ........................................................................................................... 51

• Suarez-Valdez v. Shearson Leahman/American Express, Inc.,

• 858 F.2d 648 (11th Cir. 1988) .......................................................................................... 51

• Trump v. Thompson,

• 20 F. 4th 10 (D.C. Cir. 2021) ........................................................................................... 32

• Trump v. Thompson,

• 142 S. Ct. 680 (2022) ................................................................................................... 29, 32

• Trump v. United States,

• 2022 WL 4366684 (11th Cir. Sept. 21, 2022) ....................................................... 2, passim

• Trump v. Vance,

• 140 S. Ct. 2412 (2020) ....................................................................................................... 32

• United States v. Asgari,

• 940 F.3d 188 (6th Cir. 2019) ............................................................................................ 41

• United States v. Chapman,

• 559 F.2d 402 (5th Cir. 1977) ................................................................................ 16, passim

• United States v. Daoud,

• 755 F.3d 479 (7th Cir. 2014) ............................................................................................ 41

• United States v. Dionisio,

• 410 U.S. 1 (1973) ............................................................................................................... 41

• United States v. Harte-Hanks Newspapers,

• 254 F.2d 366 (5th Cir. 1958) ............................................................................................ 23

• *United States v. Nixon,

• 418 U.S. 683 (1974) ................................................................................................. 3, passim

• United States v. O’Hara,

• 301 F.3d 563 (7th Cir. 2002) ............................................................................................ 41

• United States v. Reynolds,

• 345 U.S. 1 (1953) ............................................................................................................... 41

• United States v. Search of Law Office, Residence, & Storage Unit,

• 341 F.3d 404 (5th Cir. 2003) ............................................................................................ 26

• United States v. Truong Dinh Hung,

• 629 F.2d 908 (4th Cir. 1980) ............................................................................................ 44

• Vital Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Alfieri,

• 23 F.4th 1282 (11th Cir. 2022) ............................................................................. 17, 18, 28

• Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson,

• 142 S. Ct. 522 (2021) ......................................................................................................... 49

• Yamaha Motor Corp. v. Calhoun,

• 516 U.S. 199 (1999) ........................................................................................................... 50

• Younger v. Harris,

• 401 U.S. 37 (1971) ....................................................................................................... 21, 25

• Statutes & Other Authorities: Page:

• 18 U.S.C. § 793............................................................................................................ 8, passim

• 18 U.S.C. § 1519 ......................................................................................................... 8, 33, 44

• 18 U.S.C. § 2071 ......................................................................................................... 8, passim

• 28 U.S.C. § 1291 ..................................................................................................................... 4

• 28 U.S.C. § 1292 ......................................................................................................... 4, passim

• 44 U.S.C. § 2201 ............................................................................................................... 5, 46

• 44 U.S.C. § 2202 ............................................................................................................... 5, 24

• 44 U.S.C. § 2203 ............................................................................................................... 5, 45

• 44 U.S.C. § 2204 ..................................................................................................................... 6

• 44 U.S.C. § 2205 ..................................................................................................................... 6

• Exec. Order 13,526, 75 Fed. Reg. 707 (Jan. 5, 2010) ............................................ 5, passim

Statutes & Other Authorities: Page:

• Fed. R. App. P. 32 ................................................................................................................ 52

• Fed. R. Crim. P. 41 ..................................................................................................... 4, passim

• Fed. R. Civ. P. 53 ............................................................................................................ 11, 21

• Fed. R. Civ. P. 65 .................................................................................................................. 14

INTRODUCTION

This appeal stems from an unprecedented order by the district court restricting an ongoing criminal investigation by prohibiting the Executive Branch from reviewing and using evidence—including highly classified government records—recovered in a court-authorized search. Before the search, Plaintiff, former President Donald J. Trump, had represented in response to a grand-jury subpoena that he had returned all records bearing classification markings. The government applied for a search warrant after developing evidence that Plaintiff’s response to the grand-jury subpoena was incomplete and that efforts may have been undertaken to obstruct the investigation. A magistrate judge found probable cause to believe that a search of Plaintiff’s premises would uncover evidence of crimes, including the unauthorized retention of national defense information and obstruction of justice. The government executed its search in accordance with filter procedures approved by the magistrate judge to ensure protection of any materials that might be subject to attorney-client privilege. The search recovered, among other evidence, roughly 100 documents bearing classification markings, including markings reflecting the highest classification levels and extremely restricted distribution.

Two weeks later, Plaintiff initiated this civil action requesting the appointment of a special master to review claims of attorney-client and executive privilege and an injunction barring the government from further review and use of the seized records in the meantime, in addition to raising claims for return of property. District courts have no general equitable authority to superintend federal criminal investigations; instead, challenges to the government’s use of the evidence recovered in a search are resolved through ordinary criminal motions practice if and when charges are filed. Here, however, the district court granted the extraordinary relief Plaintiff sought, enjoining further review or use of any seized materials, including those bearing classification markings, “for criminal investigative purposes” pending a special-master review process that will last months. DE.64:23-24. This Court has already granted the government’s motion to stay that unprecedented order insofar as it relates to the documents bearing classification markings. The Court should now reverse the order in its entirety for multiple independent reasons.

Most fundamentally, the district court erred in exercising equitable jurisdiction to entertain Plaintiff’s action in the first place. The exercise of equitable jurisdiction over an ongoing criminal investigation is reserved for exceptional circumstances, and Plaintiff failed to meet this Court’s established standards for exercising that jurisdiction here. The district court itself acknowledged that there has been no showing that the government acted in “callous disregard” of Plaintiff’s rights. As a panel of this Court rightly determined, that by itself “is reason enough to conclude that the district court abused its discretion in exercising equitable jurisdiction here.” Trump v. United States, 2022 WL 4366684, at *7 (11th Cir. Sept. 21, 2022) (granting motion to stay). The remaining factors under this Court’s precedent likewise dictate that the district court’s exercise of jurisdiction was error. The Court should therefore vacate the district court’s order with instructions to dismiss Plaintiff’s civil action.

Even if the district court properly exercised jurisdiction, it erred in ordering a special-master review for claims of executive and attorney-client privilege and enjoining the government’s use of the seized records in the meantime. Plaintiff has no basis to assert executive privilege to preclude review of Executive Branch documents by “the very Executive Branch in whose name the privilege is invoked.” Nixon v. Administrator of General Services, 433 U.S. 425, 447-48 (1977) (Nixon v. GSA). Even if such an assertion could be plausible in some circumstances, executive privilege is a qualified privilege that is overcome where, as here, there is a “demonstrated, specific need” for evidence in criminal proceedings. United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 713 (1974). And although that conclusion applies to all of the seized records, it is especially true as to the records bearing classification markings because those records are central to—indeed, the very objects of—the government’s ongoing criminal investigation.

Nor has Plaintiff asserted a claim of personal attorney-client privilege that would justify the district court’s order. He has no plausible claim of such a privilege with respect to the records bearing classification markings or any other government documents related to his official duties. And neither Plaintiff nor the district court demonstrated why the filter procedures here were insufficient to protect any potential claims of personal privilege with respect to any remaining documents. The Court should therefore reverse the district court’s injunction and end the special master’s review.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The district court purported to exercise jurisdiction pursuant to Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41(g) and its equitable jurisdiction. On September 5, 2022, the district court entered an order enjoining the government from further review and use of the seized records for criminal investigative purposes pending review by a special master of Plaintiff’s claims of executive and attorney-client privilege. DE.64. On September 8, 2022, the government filed a timely appeal. DE.68. This Court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1) and 28 U.S.C. § 1291. See infra Part III.

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

1. Whether the district court erred in exercising jurisdiction over Plaintiff’s request for injunctive and other relief to constrain the government’s review and use of all records seized pursuant to a court-authorized search in an ongoing criminal investigation.

2. Whether the district court erred by enjoining the government from reviewing and using records seized during that search for criminal investigative purposes, including records bearing classification markings, pending a months-long special-master review of Plaintiff’s claims of executive and attorney-client privilege.

3. Whether the district court erred by ordering a special-master review of all seized records, including records bearing classification markings, where Plaintiff has no plausible claims of executive privilege and where the government implemented filter procedures to identify and protect attorney-client communications.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Factual Background

Plaintiff’s term of office ended in January 2021. Over the next year, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) endeavored to recover what appeared to be missing records subject to the Presidential Records Act (PRA), 44 U.S.C. § 2201 et seq. DE.48-1:6. The PRA provides that the United States retains “complete ownership, possession, and control of Presidential records,” 44 U.S.C. § 2202, which include all records “created or received by the President” or his staff “in the course of conducting activities which relate to or have an effect upon” the President’s official duties, id. § 2201(2). The PRA specifies that when a President leaves office, NARA “shall assume responsibility for the custody, control, and preservation of, and access to, the Presidential records of that President.” Id. § 2203(g)(1).

In response to repeated requests from NARA, Plaintiff eventually provided NARA with 15 boxes of records in January 2022. DE.48-1:6. NARA discovered that the boxes contained “items marked as classified national security information, up to the level of Top Secret and including Sensitive Compartmented Information and Special Access Program materials.” Id. Material is marked as Top Secret if its unauthorized disclosure could reasonably be expected to cause “exceptionally grave damage” to national security. Exec. Order 13,526 § 1.2(1), 75 Fed. Reg. 707, 707 (Jan. 5, 2010).

NARA referred the matter to the Department of Justice (DOJ), noting that highly classified records appeared to have been improperly transported and stored. MJ- DE.125:7-8.1 DOJ then sought access from NARA to the 15 boxes under the PRA’s procedures governing presidential records in NARA’s custody. DE.48-1:6-7; see 44 U.S.C. § 2205(2)(B). Plaintiff, after receiving notification of the government’s request, requested multiple extensions of the production date and purported to make “a protective assertion of executive privilege” with regard to the materials. DE.48-1:7. On May 10, 2022, NARA explained to Plaintiff that any assertion of executive privilege would be overcome by the need for evidence in a criminal investigation and informed him that the records would be produced to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). DE.48-1:9. Plaintiff did not pursue any claim of executive privilege in court, see 44 U.S.C. § 2204(e), and he did not suggest that any documents bearing classification markings had been declassified.

During this time, the FBI developed evidence that additional boxes remaining at Plaintiff’s residence at the Mar-a-Lago Club in Palm Beach, Florida, were also likely to contain classified information.2 On May 11, 2022, Plaintiff’s counsel was served with a grand-jury subpoena for “[a]ny and all documents or writings in the custody or control of Donald J. Trump and/or the Office of Donald J. Trump bearing classification markings.” DE.48-1:11.

In response, Plaintiff’s counsel and his custodian of records produced an envelope containing 37 documents bearing classification markings. MJ-DE.125:20-21.3 Plaintiff’s representatives did not assert any claim of privilege and did not suggest that any documents bearing classification markings had been declassified. To the contrary, the envelope had been wrapped in tape in a manner “consistent with an effort to handle the documents as if they were still classified.” MJ-DE.125:22. Some of the documents in the envelope bore classification markings at the highest levels, including additional compartmentalization. MJ-DE.125:21. Plaintiff’s counsel represented that the records came from a storage room at Mar-a-Lago; that all records removed from the White House had been placed in that storage room; and that no such records were in any other location at Mar-a-Lago. MJ-DE.125:20-22. Plaintiff’s custodian produced a written certification “on behalf of the Office of Donald J. Trump” that a “diligent search was conducted of the boxes that were moved from the White House to Florida” and that “[a]ny and all responsive documents accompany this certification.” DE.48-1:16.

The FBI then uncovered evidence that the response to the grand-jury subpoena was incomplete, that classified documents likely still remained at Mar-a-Lago, and that efforts may have been undertaken to obstruct the investigation. On August 5, 2022, the government applied to a magistrate judge in the Southern District of Florida for a search warrant, citing 18 U.S.C. § 793 (willful retention of national defense information), 18 U.S.C. § 2071 (concealment or removal of government records), and 18 U.S.C. § 1519 (obstruction of justice). MJ-DE.57:3. The government submitted a detailed affidavit demonstrating the bases for finding probable cause that evidence of those crimes would be found at Mar-a-Lago. MJ-DE.125. Magistrate Judge Reinhart found probable cause and authorized the government to seize “[a]ll physical documents and records constituting evidence, contraband, fruits of crime, or other items illegally possessed in violation of 18 U.S.C. §§ 793, 2071, 1519,” including, inter alia, “[a]ny physical documents with classification markings, along with any containers/boxes . . . in which such documents are located, as well as any other containers/boxes that are collectively stored or found together with the aforementioned documents and container/boxes”; and “[a]ny government and/or Presidential Records created” during Plaintiff’s term of office. MJ-DE.125.

Magistrate Judge Reinhart also approved the government’s proposed filter protocols for handling any materials potentially subject to attorney-client privilege. MJDE. 125:31-32. The filter protocols provided that special agents assigned to a filter team would conduct the search of Plaintiff’s office and would “identify and segregate documents or data containing potentially attorney-client privileged information.” MJDE. 125:31. “If at any point the law-enforcement personnel assigned to the investigation . . . identif[ied] any data or documents that they consider may be potentially attorney-client privileged,” they were required to “cease the review” of the material and “refer the materials to the [filter team] for further review.” Id. Any document deemed to be “potentially attorney-client privileged” was barred from disclosure to the investigative team. Id. The filter procedures specified that a filter attorney could apply ex parte to the court for a determination of privilege, defer seeking court intervention, or disclose the document to the potential privilege holder to obtain the potential privilege holder’s position and submit any disputes to the court. MJDE. 125:31-32.

The government executed the search on August 8, 2022. The investigative team elected for the filter team agents to conduct the initial search of the storage room in addition to Plaintiff’s office, using the same filter protocols. DE.40:3. The search recovered roughly 13,000 documents totaling approximately 22,000 pages from the storage room and Plaintiff’s private office, including roughly 100 documents bearing classification markings, with some indicating the highest levels of classification and extremely limited distribution. See DE.116-1 (inventory); DE.48-1:18 (photograph).4 In some instances, even FBI counterintelligence personnel and DOJ attorneys required additional clearances to review the seized documents. DE.48:12-13.

B. Procedural History

1. Initiation of Plaintiff’s suit

On August 22, two weeks after the search, Plaintiff initiated a civil action in the Southern District of Florida, filing a pleading styled as a “Motion for Judicial Oversight and Additional Relief.” DE.1. Among other things, Plaintiff asked the district court to appoint a special master to adjudicate potential claims of executive and attorney-client privilege and to enjoin DOJ from further review and use of the seized records. Id. The cover sheet accompanying Plaintiff’s filing described his cause of action as a “[m]otion for appointment of Special Master and other relief related to anticipated motion under F. R. Crim. P. 41(g),” DE.1-1, but Plaintiff’s motion described no basis on which he was invoking the district court’s jurisdiction. After the district court directed Plaintiff to provide a supplemental filing elaborating on, inter alia, the asserted basis for the exercise of the court’s jurisdiction, DE.10, Plaintiff asserted that the court had jurisdiction pursuant to “the Court’s equitable and ancillary jurisdiction, as well as Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 53,” DE.28:1; see also DE.28:8.5 Plaintiff also described potential proceedings pursuant to Rule 41(g), which states that a “person aggrieved by an unlawful search and seizure of property or by the deprivation of property may move for the property’s return.” See DE.28:4, DE.28:8-10.

On August 27, before receiving a response from the government, the district court issued an order setting out its “preliminary intent to appoint a special master.” DE.29. At the court’s direction, the investigative team and filter team filed notices on August 30 explaining the status of their respective reviews of the seized materials, along with detailed lists of the seized property in each team’s custody. DE.39; DE.40; see DE.29:2.6

The filter team explained that it undertook the initial search of Plaintiff’s office and the storage room, taking “a broad view of potentially privileged information, to include any documents to, from, or even referencing an attorney (regardless of whether the document appeared to capture communications to or from an attorney for the purpose of seeking legal advice and regardless of who the attorney represented),” and “treat[ing] any legal document as potentially privileged.” DE.40:3-4. The filter team also set forth the steps it proposed to resolve any potential attorney-client privilege disputes, noting that only a limited number of the materials it had segregated appeared to be even potentially privileged. DE.40:7-9. The filter team also described two instances in which members of the investigative team followed the filter protocol and ceased review of certain materials, providing them to the filter team because they fit the filter protocols’ broad prophylactic criteria for identifying materials that might be subject to attorney-client privilege. DE.40:5-7 & n.6.

2. The district court’s order and stay proceedings

a. On September 5, 2022, the district court granted Plaintiff’s motion in large part, ordering that a “special master shall be APPOINTED to review the seized property, manage assertions of privilege and make recommendations thereon, and evaluate claims for return of property.” DE.64:23. The district court further “ENJOINED” the government from “further review and use of any of the materials seized . . . for criminal investigative purposes pending resolution of the special master’s review.” Id. The court stated that the government “may continue to review and use the materials seized for purposes of intelligence classification and national security assessments.” DE.64:24.

The district court acknowledged that the exercise of equitable jurisdiction to restrain a criminal investigation is “reserved for ‘exceptional’ circumstances.” DE.64:8 (quoting Hunsucker v. Phinney, 497 F.2d 29, 32 (5th Cir. 1974)).7 The court also found that Plaintiff had not shown that the court-authorized search was in “callous disregard” of Plaintiff’s constitutional rights. DE.64:9. But the court concluded that the other considerations set forth in Richey v. Smith, 515 F.2d 1239 (5th Cir. 1975), favored the exercise of jurisdiction, principally because the seized materials included some of Plaintiff’s “personal documents.” DE.64:9-12. The court similarly found that Plaintiff had standing because he had made “a colorable showing of a right to possess at least some of the seized property,” namely, his personal effects and records potentially subject to personal attorney-client privilege. DE.64:13.

The district court found that “review of the seized property” was necessary to adjudicate Plaintiff’s claims for return of property and potential assertions of privilege. DE.64:14-19. As to attorney-client privilege, the court concluded that further review would ensure that the filter process approved by Magistrate Judge Reinhart had not overlooked privileged material. DE.64:15-16. The court did not resolve the government’s arguments that a former President cannot successfully assert executive privilege to prevent the Executive Branch from reviewing its own records and that any assertion of privilege would in any event be overcome here by the government’s demonstrated, specific need for evidence in criminal investigation. Instead, the court stated only that “even if any assertion of executive privilege by Plaintiff ultimately fails,” he should be allowed “to raise the privilege as an initial matter” during the special-master review. DE.64:17-18.

The court stated that an injunction against the government’s review and use of the seized records for criminal investigative purposes was appropriate “in natural conjunction with th[e] appointment [of the special master], and consistent with the value and sequence of special master procedures.” DE.64:1. The court determined that injunctive relief was consistent with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65, stating that Plaintiff had established “a likelihood of success on the merits of his challenge to the [filter team] and its protocol.” DE.64:20 (internal quotations and brackets omitted). The court further stated that Plaintiff had “sufficiently established irreparable injury” due to “the risk that the Government’s filter review process will not adequately safeguard Plaintiff’s privileged and personal materials.” DE.64:21. Finally, the court concluded that “the public and private interests at stake support a temporary enjoinment on the use of the seized materials for investigative purposes.” DE.64:22.

b. On September 8, the government filed a notice of appeal from the district court’s September 5 order, DE.68, and moved the district court for a partial stay of the order as it applied to records bearing classification markings, DE.69. In support of its motion, the government submitted a declaration from the Assistant Director of the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division explaining that the Intelligence Community’s national security review of these records was “inextricably linked” to the criminal investigation, and that the court’s injunction irreparably harmed the government’s ability to assess the full scope of the risk to national security posed by the improper storage of these records. DE.69-1:5.

On September 15, the district court denied the government’s motion for a partial stay. DE.89. The court declined to address the government’s argument that the classified records are not subject to any plausible claim for return or assertion of privilege. Instead, the court referred generally to “factual and legal disputes as to precisely which materials constitute personal property and/or privileged materials.” DE.89:4. The court reiterated that the injunction in its September 5 order preventing the government from using those records for criminal investigative purposes was necessary “to reinforce the value of the Special Master.” DE.89:7.

c. On September 16, the government asked this Court for a partial stay of the district court’s September 5 order, again to the extent it applied to records bearing classification markings. On September 21, a three-judge panel granted the government’s motion and stayed the order “to the extent it enjoins the government’s use of the classified documents and requires the government to submit the classified documents to the special master for review.” Trump, 2022 WL 4366684, at *12.

The Court agreed with the government that “the district court likely erred in exercising its jurisdiction to enjoin the United States’s use of the classified records in its criminal investigation and to require the United States to submit the marked classified documents to a special master for review.” Id. at *7. The Court explained that when a person seeks the return of seized property in a pre-indictment posture, the action is “governed by equitable principles” regardless of whether it is based on Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41(g) or the district court’s general equitable jurisdiction. Id. at *7 (quoting Richey, 515 F.2d at 1243). The Court then turned to “the ‘foremost consideration’ in determining whether a court should exercise its equitable jurisdiction,” which is whether the government “‘displayed a callous disregard for constitutional rights’ in seizing the items at issue.” Id. (quoting Richey, 515 F.2d at 1243-44, and United States v. Chapman, 559 F.2d 402, 406 (5th Cir. 1977)) (alteration omitted). The Court emphasized the district court’s conclusion “that Plaintiff did not show that the United States acted in callous disregard of his constitutional rights,” and that “[n]o party contests [this] finding.” Id. The Court held that “[t]he absence of this ‘indispensable’ factor in the Richey analysis is reason enough to conclude that the district court abused its discretion in exercising equitable jurisdiction here.” Id. (quoting Chapman, 559 F.2d at 406) (alteration omitted).

Although it held that the first Richey factor was dispositive, the Court considered the remaining Richey factors “for the sake of completeness” as applied to the records bearing classification markings. Id. It concluded that “none of the Richey factors favor exercising equitable jurisdiction over this case.” Id. at *9.

3. The special master proceedings

While the government’s stay motions were pending, the special master review process commenced. On September 15, the district court appointed Senior District Judge Raymond Dearie, who had been proposed by Plaintiff, as special master, DE.91; see DE.83:2, and set forth the promised “exact details and mechanics of []his review process,” DE.64:23. Among other things, the court ordered the government to provide Plaintiff’s counsel with copies of all non-classified documents and to make the records bearing classification markings available for review not only by the special master, but also by Plaintiff’s counsel. DE.91:4. The court set a deadline of November 30, 2022, for the special master to complete his review and make recommendations to the district court. DE.91:5. The order also states that “[t]he parties may file objections to, or motions to adopt or modify, the Special Master’s scheduling plans, orders, reports, or recommendations.” DE.91:6. The district court has since sua sponte extended the November 30 deadline to December 16. DE.125:5.

4. Other appellate proceedings

On October 4, Plaintiff filed an application in the Supreme Court seeking to vacate in part this Court’s partial stay, asserting that this Court lacked jurisdiction to review the portion of the district court’s September 5 order requiring that the records bearing classified markings be submitted to the special master. On October 13, the Supreme Court denied the application. Trump v. United States, No. 22A283.

C. Standards of Review

This Court reviews a district court’s decision to exercise equitable jurisdiction over an ongoing criminal investigation for abuse of discretion. Richey, 515 F.2d at 1243. The Court likewise “review[s] for abuse of discretion a ruling on a motion for a preliminary injunction.” Vital Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Alfieri, 23 F.4th 1282, 1288 (11th Cir. 2022). A district court “necessarily abuse[s] its discretion if it base[s] its ruling on an erroneous view of the law or on a clearly erroneous assessment of the evidence.” Cooter & Gell v. Hartmarx Corp., 496 U.S. 384, 405 (1990); see also Vital Pharmaceuticals, 23 F.4th at 1288 (similar). The Court “review[s] de novo questions of [its own] jurisdiction.” Vital Pharmaceuticals, 23 F. 4th at 1288 (internal quotations omitted).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. The district court erred by exercising equitable jurisdiction in this case. The exercise of such jurisdiction over a pre-indictment criminal investigation is limited to exceptional cases. Under this Court’s precedent, it requires, at a minimum, a showing that the government callously disregarded Plaintiff’s constitutional rights. Nothing like this was shown in this case, as the district court acknowledged.

The remaining equitable factors weigh against jurisdiction as well. Plaintiff has shown no need for the materials at issue. Nor has he shown any likelihood that he will be irreparably harmed by adhering to the ordinary process in which any challenges to the government’s use of evidence recovered in a search are raised and resolved— through standard motions practice in criminal proceedings in the event that charges are brought. This Court should therefore vacate the district court’s September 5 order in its entirety with instructions to dismiss the case.

II. Even if it properly exercised jurisdiction, the district court erred in enjoining the government from further review and use of the seized records pending a special- master review of Plaintiff’s claims of executive and attorney-client privilege. Executive privilege exists “for the benefit of Republic,” not any President as an individual, and Plaintiff cannot successfully invoke the privilege to prevent a review of Executive Branch documents by “the very Executive Branch in whose name the privilege is invoked.” Nixon v. GSA, 433 U.S. at 447-49. Even if Plaintiff could assert such a claim, it would be overcome here by the government’s “demonstrated, specific need” for evidence in a criminal investigation. United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. at 713. The government’s need for the records bearing classification markings is especially compelling because those records are the very object of the government’s investigation of potential violations of 18 U.S.C. § 793.

Nor was an injunction necessary to protect Plaintiff’s potential claims of attorney-client privilege. The government’s filter team had already segregated any records potentially covered by the privilege, and its filter procedures barred disclosure of those records to the investigative team unless or until either Plaintiff declined to assert attorney-client privilege or the court adjudicated any privilege disputes.

None of the other factors governing the issuance of a preliminary injunction supported the extraordinary relief granted by the district court. Plaintiff failed to demonstrate that he would suffer irreparable harm absent an injunction, and the injunction overwhelmingly harms the government and the public interest. Lastly, none of the factual disputes suggested by Plaintiff supports any entitlement to injunctive relief. His suggestion that he could have declassified the records bearing classification markings is unsubstantiated and irrelevant here, and his suggestion that he could have designated government records as his “personal” records under the PRA would only undermine any claim of executive privilege.

III. For those reasons, both the injunction and the special-master review ordered by the district court were unwarranted and should be reversed. This Court has jurisdiction to address the special-master review for at least three independent reasons. First, as the Court concluded in granting a partial stay, the Court has pendent jurisdiction to review the special-master portion of the order below because it is “inextricably intertwined” with the concededly appealable injunction. Trump, 2022 WL 4366684, at *6 n.3. Second, 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1) provides for interlocutory review of district court “orders” granting injunctions. Appellate jurisdiction thus lies over the entire order granting an injunction, as the Supreme Court has held in interpreting other statutes granting jurisdiction to review particular types of “orders.” Third, the collateral order doctrine provides an independent basis for appellate jurisdiction over orders requiring disclosure of classified information.

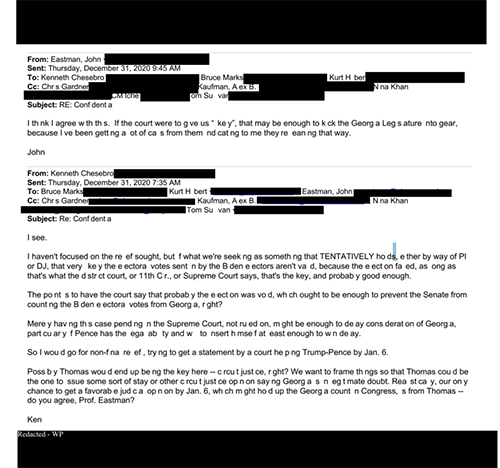

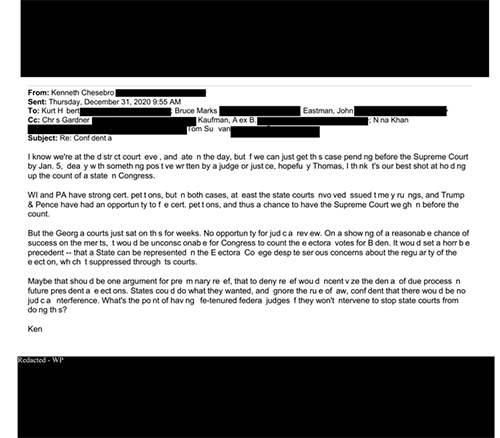

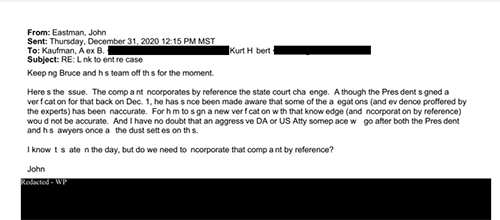

Trump lashes out at Gov. Doug Ducey following certification

Re: Trump lashes out at Gov. Doug Ducey following certificat

Part 2 of 2

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN EXERCISING EQUITABLE JURISDICTION

District courts have no general equitable authority to superintend federal criminal investigations. A district court’s exercise of civil equitable jurisdiction to constrain an ongoing criminal investigation prior to indictment is limited to “exceptional” circumstances. Hunsucker v. Phinney, 497 F.2d 29, 32 (5th Cir. 1974). That is consistent with the “familiar rule that courts of equity do not ordinarily restrain criminal prosecutions.” Douglas v. City of Jeanette, 319 U.S. 157, 163 (1943); see also Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37, 43-44 (1971). Whether a plaintiff seeks to invoke a district court’s jurisdiction based on Rule 41(g) or “the general equitable jurisdiction of the federal courts,”8 this Court has instructed that a district court must consider four factors before exercising jurisdiction to entertain a preindictment motion for return of property. Richey, 515 F.2d at 1243-44. These factors are: (1) whether the government has “displayed ‘a callous disregard for the constitutional rights’” of the plaintiff; (2) “whether the plaintiff has an individual interest in and need for the material”; (3) “whether the plaintiff would be irreparably injured by denial of the return of the property”; and (4) “whether the plaintiff has an adequate remedy at law.” 515 F.2d at 1243-44 (citation omitted).

Plaintiff’s uncontested failure to satisfy the first factor—which this Court has described as “foremost” and even “indispensab[le],” Chapman, 559 F.2d at 406—is reason enough to conclude that the district court erred by exercising jurisdiction in this case. The remaining Richey factors likewise do not support the district court’s exercise of jurisdiction.

A. Plaintiff Failed to Establish the “Foremost” Factor Needed for the Exercise of Jurisdiction

As the stay panel observed, the first Richey factor—whether the government displayed a “callous disregard” for constitutional rights—is both the “foremost consideration” and is “indispensab[le].” Trump, 2022 WL 4366684, at *7 (quoting Chapman, 559 F.2d at 406). That factor is wholly absent here. To the contrary, the government first sought these records through voluntary requests. DOJ then obtained a subpoena and gave Plaintiff a chance to return all responsive records. Only when investigators learned that Plaintiff’s response was likely incomplete did they seek a search warrant. A magistrate judge issued that warrant after finding probable cause, based on the government’s lengthy affidavit, that evidence of multiple criminal violations would be found at Plaintiff’s residence. MJ-DE.125. The records at issue here are the documents recovered pursuant to that court-approved warrant, after earlier attempts to retrieve them had failed. The district court accordingly determined that Plaintiff had demonstrated no “callous disregard” of his rights. DE.64:9; see, e.g., Hunsucker, 497 F.2d at 34 (“since the search in issue was conducted pursuant to a warrant issued in the normal manner,” the court could not “say that the [underlying] action . . . involved a callous disregard for constitutional rights” (internal quotations and alteration marks omitted)); In re Search of 4801 Fyler Ave., 879 F.2d 385, 388 (8th Cir. 1989) (“officers acted in objective good faith, rather than with callous disregard for” plaintiff’s rights, where agents “first obtained a warrant . . . using a lengthy and detailed affidavit . . . to establish probable cause”).

This Court correctly held that “[t]he absence of this ‘indispensable’ factor in the Richey analysis is reason enough to conclude that the district court abused its discretion in exercising equitable jurisdiction here.” Trump, 2022 WL 4366684, at *7 (quoting Chapman, 559 F.2d at 406) (alteration omitted); see also United States v. Harte-Hanks Newspapers, 254 F.2d 366, 369 (5th Cir. 1958) (“suppression of evidence prior to an indictment should be considered only when there is a clear and definite showing that constitutional rights have been violated”); In re Search of 4801 Fyler Ave., 879 F.2d at 387 (“jurisdiction is proper only upon a showing of callous disregard of the [F]ourth [A]mendment”). Although the Court had occasion to address only the district court’s exercise of jurisdiction with regard to the documents bearing classification markings, the same analysis applies to all of the seized materials—and, thus, the entire proceeding. And as the Court held, that by itself is sufficient reason to conclude that the district court erred in exercising jurisdiction over this action. Trump, 2022 WL 4366684, at *7.

B. The Remaining Richey Factors Weigh Further Against the Exercise of Jurisdiction

As the Court explained with respect to the documents bearing classification markings, the remaining Richey factors likewise weighed against the exercise of jurisdiction. Trump, 2022 WL 4366684, at *7-9. Similar logic applies to the other seized materials, and the district court abused its discretion in concluding otherwise.

The second Richey factor considers “whether the plaintiff has an individual interest in and need for the material whose return he seeks.” 515 F.2d at 1243. Plaintiff has no individual interest in any official government records: the government “retain[s] complete ownership, possession, and control of Presidential records,” 44 U.S.C. § 2202, and records bearing classification markings in particular contain information that “is owned by, produced by or for, or is under the control of the” government, Exec. Order No. 13,526, § 1.1(2), 75 Fed. Reg. at 707. Moreover, Plaintiff made no showing of a need for the return of any personal documents that were seized. See Ramsden v. United States, 2 F.3d 322, 325-26 (9th Cir. 1993) (mere interest in property does not indicate a need for its return). The district court simply assumed Plaintiff’s interest in and need for some unidentified portion of the records “based on the volume and nature of the seized material.” DE.64:9. But it was Plaintiff’s burden to justify the exercise of jurisdiction, and he has identified nothing about the volume or the nature of the seized material to suggest that this case presents the “exceptional” circumstances, Hunsucker, 497 F.2d at 32, that could justify the invocation of equitable jurisdiction over a pre-indictment criminal investigation.

The third Richey factor asks “whether the plaintiff would be irreparably injured by denial of the return of the property.” 515 F.2d at 1243. Plaintiff failed to establish any injury—let alone any irreparable injury—caused by his being deprived of the materials. And the injuries described by the district court, far from constituting exceptional circumstances justifying equitable jurisdiction, were both wholly speculative and could be claimed by anyone whose property was seized in a criminal investigation. For example, the district court noted that the government’s filter process “thus far[] has been closed off to Plaintiff.” DE.64:10. But that fact is hardly extraordinary; the use of a filter team is a common way “to sift the wheat from the chaff” and “constitutes an action respectful of, rather than injurious to, the protection of [attorney-client] privilege.” In re Grand Jury Subpoenas, 454 F.3d 511, 522-23 (6th Cir. 2006); accord In re Sealed Search Warrant, No. 20-MJ-3278, 2020 WL 6689045, at *2 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 2, 2020) (“it is well established that filter teams—also called ‘taint teams’—are routinely employed to conduct privilege reviews”), aff’d, 11 F.4th 1235 (11th Cir. 2021).

In any event, Plaintiff’s counsel was given contact information for one of the filter attorneys on the day the search was executed. DE.127:42 (transcript). Indeed, the filter team had finished its review and was prepared to provide Plaintiff’s counsel with copies of all potentially privileged materials when the court issued its preliminary notice of intent to appoint a special master. DE.127:49; see DE.40:2. The government’s filter attorney explained that the filter team “put a pause on that process” out of deference to the court’s proceedings, DE.127:49, and sought the court’s permission to produce the materials to Plaintiff’s counsel, DE.127:52-53. The court instead “reserve[d] ruling on that request.” DE.127:53.

The district court also referred to Plaintiff’s supposed “injury from the threat of future prosecution,” DE.64:10, but that is not “considered ‘irreparable’ in the special legal sense of that term,” Younger, 401 U.S. at 46. As this Court already explained, “if the mere threat of prosecution were allowed to constitute irreparable harm[,] every potential defendant could point to the same harm and invoke the equitable powers of the district court.” Trump, 2022 WL 4366684, at *8 (quoting United States v. Search of Law Office, Residence, & Storage Unit, 341 F.3d 404, 415 (5th Cir. 2003)) (alteration omitted). That would improperly transform equitable jurisdiction from “extraordinary” to “quite ordinary.” Id. (quoting Search of Law Office, Residence, & Storage Unit, 341 F.3d at 415); see also Ramsden, 2 F.3d at 326.

The fourth Richey factor is “whether the plaintiff has an adequate remedy at law.” 515 F.2d at 1243. To the extent Plaintiff wishes to contest the legality of the search or to assert any claims of privilege, he may do so through ordinary motions practice in a criminal proceeding in the event that charges are filed. But absent extraordinary circumstances, “[p]rospective defendants cannot, by bringing ancillary equitable proceedings, circumvent federal criminal procedure.” Deaver v. Seymour, 822 F.2d 66, 71 (D.C. Cir. 1987).

Finally, the other factors that the district court considered have no basis in precedent and cannot justify the exercise of equity jurisdiction. Certain of these factors, such as “the power imbalance between the parties” and Plaintiff’s “inability to examine the seized materials,” DE.64:11, are hardly extraordinary and exist whenever a lawfully obtained search warrant is executed. And to the extent the district court suggested that Plaintiff’s former elected office entitles him to treatment different from that afforded to any other subject of a court-authorized search, DE.64:10; DE.64:22, such a notion would be contrary to the public interest and the rule of law.

* * *

In short, the district court erred in exercising equitable jurisdiction over this action. The uncontested record demonstrates that the search was conducted in full accordance with a judicially authorized warrant, and there has been no violation of Plaintiff’s rights—let alone a “callous disregard” for them. Plaintiff has failed to meet his burden in establishing any need for the seized records—indeed, a substantial number of them are not even his—or in establishing any irreparable injury in their absence, and Plaintiff does not lack an adequate alternative remedy at law. This Court should therefore reverse the district court’s September 5 order with instructions to dismiss Plaintiff’s civil action.9

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED BY ENJOINING THE GOVERNMENT FROM REVIEWING OR USING THE SEIZED RECORDS

Even if the district court properly exercised equitable jurisdiction, it erred by issuing an injunction preventing the government from using any of the lawfully seized materials in its ongoing investigation pending the special-master review for claims of privilege. To obtain a preliminary injunction, Plaintiff was required to establish (1) “a substantial likelihood of success on the merits”; (2) that “irreparable injury [would] be suffered” absent an injunction; (3) that “the threatened injury to [Plaintiff] outweighs whatever damage the proposed injunction may cause the opposing party”; and (4) that an injunction “would not be adverse to the public interest.” Vital Pharmaceuticals, 23 F. 4th at 1290-91. Plaintiff did not satisfy those requirements.

As to the likelihood of success on the merits, Plaintiff has no plausible claim of executive privilege, nor has he attempted to describe any, that could bar the government’s review and use of any the seized records—classified or unclassified. Further, to the extent Plaintiff has any plausible claims of personal attorney-client privilege regarding the seized records, those claims do not pertain to records bearing classification markings, and Plaintiff has failed to establish any irreparable injury he would suffer from permitting the government to review and use those records not already segregated by the filter team. By contrast, the government and public interest are harmed by the unprecedented injunction and order entered by the district court.

A. Plaintiff Has No Plausible Claims of Executive Privilege

Plaintiff has no plausible claim of executive privilege that could justify restricting the Executive Branch’s review and use of the seized records in the performance of core executive functions. Plaintiff has never even attempted to substantiate such a claim, and any such claim would fail for multiple independent reasons.

1. Plaintiff cannot invoke executive privilege to bar the Executive Branch’s review and use of its own records

Executive privilege exists “not for the benefit of the President as an individual, but for the benefit of the Republic.” Nixon v. GSA, 433 U.S. at 449. It protects the “legitimate governmental interest in the confidentiality of communications between high Government officials,” because “‘those who expect public dissemination of their remarks may well temper candor.’” Id. at 446 n.10 (quoting United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. at 705). Consistent with the privilege’s function of protecting the Executive Branch’s institutional interests, the privilege may be invoked in certain instances to prevent the dissemination of materials outside the Executive Branch. E.g., Trump v. Thompson, 142 S. Ct. 680, 680 (2022) (per curiam) (materials requested by a Congressional committee). But neither Plaintiff nor the district court has cited any instance in which executive privilege was successfully invoked to prohibit the sharing of records or information within the Executive Branch itself.

To the contrary, in what appears to be the only case in which such an assertion was made, the Supreme Court rejected former President Nixon’s claim that he could assert executive privilege “against the very Executive Branch in whose name the privilege is invoked.” Nixon v. GSA, 433 U.S. at 447-48. The Court thus upheld the requirement in the Presidential Records and Materials Preservation Act (a precursor to the PRA) that personnel in the General Services Administration review documents and recordings created during his presidency. Although the Court stated that a former President may be able to invoke executive privilege after the conclusion of his tenure in office, see id. at 448-49, it “readily” rejected the argument that the privilege could bar review of records by “personnel in the Executive Branch sensitive to executive concerns.” Id. at 451.

Here, any assertion of executive privilege would similarly be made against “the very Executive Branch in whose name the privilege is invoked,” id. at 447-48, and it would be invalid for the same reasons. In this case, as in Nixon v. GSA, the officials reviewing the seized records are “personnel in the Executive Branch sensitive to executive concerns.” Id. at 451. Indeed, the circumstances here dictate that these records will be treated with heightened sensitivity: they were seized pursuant to a search warrant in a criminal and national security investigation; they are in the custody of the FBI; and they must be safeguarded as evidence, including through appropriate chain-of-custody controls. Further, the seized records bearing classification markings must be stored in approved facilities, and officials reviewing them must possess the appropriate level of security clearance and must have the requisite “need to know.” See Exec. Order 13,526 § 4.1(a), (g), 75 Fed. Reg. at 720-21.

Of course, the purpose of the Executive Branch’s review here differs from that in Nixon v. GSA. The review at issue there involved the “screen[ing] and catalogu[ing]” of Presidential materials “by professional archivists” to carry out a statutory scheme designed to “preserve the materials for legitimate historical and governmental purposes.” 433 U.S. at 450, 452. Here, the review is to be conducted by law enforcement and intelligence personnel as part of an ongoing criminal investigation and for purposes of assessing the potential damage to national security posed by the improper storage of records with classification markings. But that distinction only weakens any potential privilege claim by Plaintiff. The execution of criminal laws and the protection of national security information are core Executive Branch responsibilities. See U.S. Const. art. II, § 3; Dep’t of Navy v. Egan, 484 U.S. 518, 527 (1988). The effective and expeditious performance of those functions serves compelling public interests. Restricting the Executive Branch’s access to information needed to carry out those functions would serve neither the purposes of executive privilege nor the public interest.

2. United States v. Nixon forecloses any executive privilege claims

This Court need not, however, definitively answer whether a former President could ever successfully invoke executive privilege to block the Executive Branch’s review of its own records, because any such invocation in this case would inevitably fail under United States v. Nixon. In that case—involving a trial subpoena and a sitting President’s assertion of executive privilege—the Supreme Court made clear that executive privilege is qualified, not absolute. In doing so, the Court emphasized that a President’s interests in confidentiality “must be considered in light of our historic commitment to the rule of law.” 418 U.S. at 708. As the Supreme Court explained more recently, the Nixon Court “observed that the public interest in fair and accurate judicial proceedings is at its height in the criminal setting, where our common commitment to justice demands that ‘guilt shall not escape’ nor ‘innocence suffer.’” Trump v. Vance, 140 S. Ct. 2412, 2424 (2020) (quoting Nixon, 418 U.S. at 709). Accordingly, the Nixon Court concluded that President Nixon’s “generalized assertion of privilege must yield to the demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal trial.” Nixon, 418 U.S. at 713. That “demonstrated, specific need” standard has since been applied in the context of investigative proceedings as well. In re Sealed Case, 121 F.3d 729, 753-57 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (grand-jury subpoena); see also Vance, 140 S. Ct. at 2432 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring) (describing the Nixon test as applying to “federal criminal subpoenas” and citing Sealed Case). Here, the government plainly has a “demonstrated, specific need” for evidence recovered pursuant to a warrant based on a judicial finding of probable cause. As explained below, that is so as to both the records bearing classification markings and the remaining seized records.10

a. The government has a “demonstrated, specific need” for the records bearing classification markings

The government’s need for the records bearing classification markings is overwhelming. It is investigating potential violations of 18 U.S.C. § 793(e), which prohibits the unauthorized retention of national defense information. These records are not merely evidence of possible violations of that law. They are the very objects of the offense and are essential for any potential criminal case premised on the unlawful retention of the materials. Likewise, these records may constitute evidence of potential violations of 18 U.S.C. § 2071, which prohibits concealment or removal of government records.

The records bearing classification markings may also constitute evidence of potential violations of 18 U.S.C. § 1519, prohibiting obstruction of a federal investigation. As described above, on May 11, 2022, Plaintiff’s counsel was served with a grand-jury subpoena for “[a]ny and all documents or writings in the custody or control of Donald J. Trump and/or the Office of Donald J. Trump bearing classification markings.” DE.48-1:11. In response, Plaintiff’s counsel produced an envelope containing 37 documents bearing classification markings, see MJ-DE.125:20-21, and Plaintiff’s custodian of records certified that “a diligent search was conducted of the boxes that were moved from the White House to Florida” and that “[a]ny and all responsive documents accompany this certification,” DE.48-1:16. As evidenced by the government’s subsequent execution of the search warrant, all responsive documents did not in fact accompany that certification: more than 100 additional documents bearing classification markings were recovered from Plaintiff’s Mar-a-Lago Club. Those documents may therefore constitute evidence of obstruction of justice.

The government’s compelling need for these records is not limited to their potential use as evidence of crimes. As explained in the stay proceedings, the government has an urgent need to use these records in conducting a classification review, assessing the potential risk to national security that would result if they were disclosed, assessing whether or to what extent they may have been accessed without authorization, and assessing whether any other classified records might still be missing. The district court itself acknowledged the importance of the government’s classification review and national security risk assessment. DE.64:22-23. The government has further explained, including through a sworn declaration by the Assistant Director of the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division, why those functions are inextricably linked to its criminal investigation. DE.69-1:3-5. For example, the government may need to use the contents of these records to conduct witness interviews or to discern whether there are patterns in the types of records that were retained. The stay panel correctly concluded that a prohibition against using the records for such purposes would cause not only harm, but “irreparable harm.” Trump, 2022 WL 4366684, at *12; see also id. at *11. Plaintiff has never substantiated any interest that could possibly outweigh these compelling governmental needs, and none exists.

b. The government has a “demonstrated, specific need” for the remaining seized records

The government also has a “demonstrated, specific need” for the seized unclassified records. The FBI recovered these records in a judicially authorized search based on a finding of probable cause of violations of multiple criminal statutes. The government sought and obtained permission from the magistrate judge to search Plaintiff’s office and any storage rooms, MJ-DE.125:37, and to seize, inter alia, “[a]ny physical documents with classification markings, along with any containers/boxes (including any other contents) in which such documents are located, as well as any other containers/boxes that are collectively stored or found together with the aforementioned documents and containers/boxes,” MJ-DE.125:38. The magistrate judge thus necessarily concluded that there was probable cause to believe those items constitute “evidence of a crime” or “contraband, fruits of crime, or other items illegally possessed.” Fed. R. Crim. P. 41(c)(1), (2); see MJ-DE.57:3.

That is for good reason. As an initial matter, the unclassified records may constitute evidence of potential violations of 18 U.S.C. § 2071, which prohibits “conceal[ing]” or “remov[ing]” government records. Moreover, unclassified records that were stored in the same boxes as records bearing classification markings or that were stored in adjacent boxes may provide important evidence as to elements of 18 U.S.C. § 793. First, the contents of the unclassified records could establish ownership or possession of the box or group of boxes in which the records bearing classification markings were stored. For example, if Plaintiff’s personal papers were intermingled with records bearing classification markings, those personal papers could demonstrate possession or control by Plaintiff.

Second, the dates on unclassified records may prove highly probative in the government’s investigation. For example, if any records comingled with the records bearing classification markings post-date Plaintiff’s term of office, that could establish that these materials continued to be accessed after Plaintiff left the White House. Third, the government may need to use unclassified records to conduct witness interviews and corroborate information. For example, if a witness were to recall seeing a document bearing classification markings next to a specific unclassified document (e.g., a photograph), the government could ascertain the witness’s credibility and potentially corroborate the witness’s statement by reviewing both documents.

In short, the unclassified records that were stored collectively with records bearing classification markings may identify who was responsible for the unauthorized retention of these records, the relevant time periods in which records were created or accessed, and who may have accessed or seen them.

3. Any claim of executive privilege as to the records bearing classification markings would fail for additional reasons

Any claim of executive privilege as to the documents bearing classification markings would fail for at least two additional reasons.

First, Plaintiff’s effort to block the Executive Branch’s access to the records bearing classification markings is inconsistent with the established principle that the incumbent President has sole authority to control access to national security information. As the Supreme Court explained in Egan, the President “is the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States,” and his “authority to classify and control access to information bearing on national security . . . flows primarily from this constitutional investment of power.” 484 U.S. at 527 (internal quotations omitted). “The authority to protect such information” thus “falls on the President as head of the Executive Branch and as Commander in Chief.” Id.; see also, e.g., Murphy v. Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t of Army, 769 F. App’x. 779, 782 (11th Cir. 2019) (“The authority to protect national security information falls on the President.”). This authority to protect “and control access to” national security information falls on the incumbent President as “Commander in Chief,” not on any former President. Egan, 484 U.S. at 527. Yet Plaintiff effectively seeks to control which Executive Branch personnel (if any) can review records marked as classified and on what terms. This he cannot do. “For ‘reasons too obvious to call for enlarged discussion,’” that authority rests with the incumbent President and the discretion of the agencies to whom the President’s authority has been delegated. Egan, 484 U.S. at 529 (quoting CIA v. Sims, 471 U.S. 159, 170 (1985) (alteration omitted)).

Second, Plaintiff failed to assert executive privilege when his custodian was served with a grand-jury subpoena requiring production of “[a]ny and all documents or writings” in Plaintiff’s custody “bearing classification markings.” DE.48-1:11. Plaintiff’s counsel never suggested that executive privilege constituted grounds for withholding any responsive records. Indeed, although Plaintiff’s counsel sent the government a three-page letter on May 25, 2022, discussing what counsel described as “a few bedrock principles,” nothing in that letter contained any reference to executive privilege. MJDE. 125:34-36. Nor did Plaintiff move to quash the subpoena on executive privilege (or any other) grounds. Instead, Plaintiff’s counsel produced an envelope on June 3, 2022, that purportedly contained “[a]ny and all responsive documents.” DE.48-1:16.

The records recovered by the government during the August 8 search that bear classification markings are the very records that Plaintiff was required to produce on June 3, and over which he raised no claim of executive privilege. Having failed to produce documents responsive to a lawful grand-jury subpoena, Plaintiff should not be rewarded with an opportunity to further delay the government’s investigation by interposing such privilege claims now. Cf. Ramirez v. Collier, 142 S. Ct. 1264, 1282 (2022) (“When a party seeking equitable relief ‘has violated conscience, or good faith, or other equitable principle, in his prior conduct, then the doors of the court will be shut against him.’” (quoting Keystone Driller Co. v. General Excavator Co., 290 U.S. 240, 245 (1933))).

B. Plaintiff Has No Plausible Claims of Attorney-Client Privilege That Would Justify an Injunction

As with executive privilege, Plaintiff has no plausible claim of personal attorneyclient privilege that would justify the injunction pending special-master review in this case. As the government has made clear, and as Plaintiff has never contested, any seized government records—including the seized records bearing classification markings—do not contain any privileged communications between Plaintiff and his personal attorneys. See DE.69:8; see also Exec. Order 13,526 § 1.1(2), 75 Fed. Reg. at 707. And although a limited number of the personal records that were seized are potentially subject to attorney-client privilege, the filter team already identified and segregated them, see DE.40, and neither Plaintiff nor the district court explained why it would be appropriate to enjoin the government’s investigative team from reviewing and using the remaining records pending a special-master review.