APPENDIX

Rule Ordinance and Regulation of 1825* [The Bombay Secretariat Records, G.D. Vol. No. 14/98 of 1825 (pp. 139-181).]

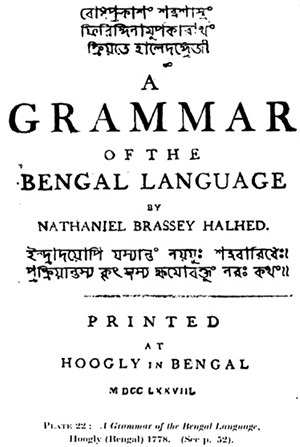

Title

A Rule Ordinance and Regulation for preventing the mischiefs arising from the printing and publishing Newspapers and Periodical Books and Papers of a like nature and also from the printing and publishing libellous matters in Books of every other description by persons not known and for regulating the printing and publication of all such Books and Papers in other respects Passed by the Hon'ble the Governor in Council of Bombay on the day of and registered in the Hon'ble the Supreme Court of Judicature at Bombay under date the day of 1825.

Preamble

Whereas for the purpose of preventing the publication of libellous matter as well in Newspapers and other Periodical Papers of that kind as in printed Books and Papers of every other description within the Presidency of Bombay, and for the purpose of more easily detecting those who may be legally responsible for the same the Hon'ble the Governor in Council has deemed expedient that certain Regulations should be provided touching publications of the nature hereinafter mentioned respectively.

Article I: No person to print or publish periodical Papers or Books without Licence

Be it therefore ordained by authority of the Hon'ble the Governor in Council and under and by virtue of a certain Act of Parliament made and passed in the Forty Seventh year of the reign of his late Majesty's King George the third instituted an Act for the better settlement of Forts of St. George and Bombay that from and after 14 days after the Registry and Publication of this Rule Ordinance and Regulation in the Supreme Court of Judicature at Bombay no person or persons shall within the said Presidency of Bombay print or publish or cause to be printed or published any Newspaper or Magazine Register Pamphlet or other printed Book or Paper whatsoever in any language or character whatsoever published periodically containing or purporting to contain public News Intelligence or Strictures on the Acts measures and Proceedings of Government or any Political events or transactions whatsoever without having obtained a licence for that purpose from the Hon'ble the Governor in Council Signed by the Chief Secretary of Government for the time being or other person officiating and acting as such Chief Secretary.

Article II: Persons applying for licence to deliver Affidavits specifying the names and places of abode of Printers Publishers and Proprietors of such Newspapers and other periodical Books together with the house wherein printed and title of the same

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, that every person applying to the Hon'ble the Governor in Council for such licence as aforesaid shall deliver to the Chief Secretary of Government for the time being or other person acting and officiating as such an Affidavit or Affidavits in writing signed by the persons making the same to be taken before any Justice of the Peace acting within the Presidency specifying and setting forth the real and true names additions descriptions and places of abode of all and every person or persons who is or are intended to be the Printer and Printers Publisher and Publishers of the Newspaper Magazine Register Pamphlet or other printed Book or Paper in such Affidavit or Affidavits mentioned and of all the Proprietors of the same resident within the Presidency of Bombay or places thereto Subordinate, if the number of such Proprietors exclusive of the Printers and Publishers does not exceed two, and in case the same shall exceed such number then of two of the Proprietors exclusive of the Printers and Publishers resident within the Presidency of Bombay or places thereto subordinate who hold the largest shares therein, and also the amount of the proportional shares of such Proprietors in the property therein, and likewise the true description of the house or building wherein any such Newspaper Magazine Register Pamphlet or other Printed Book or Paper as aforesaid is intended to be printed, and the title of such Newspaper Magazine Register Pamphlet or other Printed Book or Paper.

Article III: Where the Printers and Publishers together with the Proprietors shall not exceed four then the Affidavits to be signed and sworn by all who are resident in Bombay where they exceed four by four or so many as are resident in Bombay

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid that where the persons concerned as Printers and Publishers of any such Newspaper, Magazine Register Pamphlet or other Printed Book or Paper as aforesaid together with such number of Proprietors as are herein before required to be named in such Affidavit or Affidavits as aforesaid shall not altogether exceed the number of four persons, the Affidavit or Affidavits hereby required shall be sworn and signed by all the said persons who are resident in or within miles of Bombay and when the number of such persons shall exceed four, the same shall be signed and sworn by four of such persons if resident in or within miles of Bombay or by so many of them as are so resident.

Article IV: New Affidavits to be made as often as the Printers Publishers or Proprietors shall be changed or shall change their places of abode or printing house and as often as the Governor in Council shall require

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid That an Affidavit or Affidavits of the like nature and import shall be made signed and delivered in like manner as often as any of the Printers, Publishers or Proprietors named in such Affidavit or Affidavits shall be changed or shall change their respective places of abode or their printing House Place or Office and as often as the title of such Newspaper Magazine Register Pamphlet or other printed Book or Paper as aforesaid shall be changed and as often as the Hon'ble the Governor in Council shall deem it expedient so to require, and that when such further and new Affidavit or Affidavits as last aforesaid shall be so required by the Hon'ble the Governor in Council notice of such requisition, signed by the said Chief Secretary or other person acting and officiating as such shall be given to the persons named in the Affidavit or Affidavits to which the said notice relates as the Printers, Publishers or Proprietors of the Newspaper, Magazine, Register Pamphlet or other printed Book or Paper in such Affidavit or Affidavits mentioned such notice to be left at such place as is mentioned in the Affidavits last delivered as the place at which the Newspaper, Magazine, Register Pamphlet or other printed Book or Paper to which such notice shall relate is printed.

Article V: Printing and Publishing Newspapers &ca. without making the Affidavits herein before required to be deemed a Printing and Publishing without Licence

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That in case any such Newspaper Magazine Register Pamphlet or other printed book or Paper as herein before described shall be printed or published such Affidavit or Affidavits as herein before required not having been duly signed sworn and delivered, the same shall be deemed and taken to be printed and published without Licence and the Printers, Publishers and Proprietors thereof shall be liable to the same Penalties as are hereinafter imposed upon Printers and Publishers of such Newspapers Magazines Registers Pamphlets and other printed Books and Papers as are hereinbefore described without Licence.

Article VI: Governor in Council to have power to recall Licences

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid that every Licence which shall and may be granted in manner and form aforesaid shall and may be resumed and recalled by the Hon'ble the Governor in Council upon notice to such effect in writing signed by the said Chief Secretary or other person acting and officiating as such being left at such place as is mentioned in the Affidavit or Affidavits last delivered as the place at which the Newspaper Magazine Register Pamphlet or other printed Book or Paper to which such notice shall relate is printed, and that from and immediately after such notice having been so left as aforesaid the said Licence or Licences shall be null and void and any Newspaper Magazine Register Pamphlet printed book or Paper to which such Licence or Licences shall have related shall if afterwards printed and published be taken and considered as printed and published without Licence. And it is hereby further ordained that whenever any such Licence shall be resumed and recalled as aforesaid notice of such resumption and recall shall be forthwith given in the for the ____ time being published in Bombay.

Article VII: Penalty of Rs. 400 on printing or publishing Newspapers &ca. without Licence

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid that if any person or persons shall within the Presidency of Bombay knowingly and wilfully print or publish, or cause to be printed or published or shall knowingly and wilfully either as a Proprietor thereof or as Agent or Servant of such Proprietor or otherwise sell deliver out, distribute or dispose of, or if any Bookseller or Proprietor or Keeper of any Reading Room Library Shop, or place of public resort, shall knowingly and wilfully receive for the purpose of publication, or lend give, or supply for the purpose of perusal or otherwise to any person whatsoever any such Newspaper Magazine Register or Pamphlet or other printed Book or Paper as hereinbefore described such Licence as is required by this Rule Ordinance and Regulation not having been first obtained or after such Licence if previously obtained shall have been recalled as aforesaid such persons shall forfeit for every such offence the sum of four hundred rupees.

Article VIII: Affidavits to be filed and they or certified copies to be admitted in all proceedings Civil or Criminal as evidence of the truth of their contents against persons swearing and all mentioned therein unless proved to the contrary. But if any person shall have delivered previous to the publication of the paper to which the proceedings relate and Affidavit that he has ceased to be the Printer &ca. he shall not be so deemed after such delivery.

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid that all such Affidavits as aforesaid shall be filed and kept in such manner as the said Justice of Peace before whom the same shall have been respectively sworn shall direct, and the same or Copies thereof certified to be true Copies as hereinafter is prescribed shall respectively in all proceedings Criminal and Civil touching any Newspaper or other such Book or Paper as hereinbefore is specified which shall be mentioned in any such Affidavit or Affidavits, or touching any publication matter or thing contained in such Newspaper or other Book or Paper as aforesaid be received and admitted as conclusive evidence of the truth of all such matters set forth in such Affidavits as are hereby required to be therein set forth against every person who shall have signed and sworn the same and also as sufficient evidence of the truth of all such matters against all and every person who shall not have signed or sworn the same, but who shall be therein mentioned to be a Proprietor, Printer or Publisher of such Newspaper or other Book or Paper as aforesaid unless the contrary shall be satisfactory proved. Provided always, That if any such person or persons respectively against whom any such Affidavit or Affidavits or any Copy thereof shall be offered in evidence shall prove that he she or they hath or have signed sworn and delivered to the said Justice of the Peace previous to the day of the date or publication of the Newspaper or other such Book or Paper as aforesaid to which the proceedings Civil or Criminal shall relate an Affidavit or Affidavits that he she or they hath or have ceased to be Printer or Printers, Proprietor or Proprietors or Publisher or Publishers of such Newspaper or other such printed Book or Paper as aforesaid such person or persons shall not be deemed by reason of any former Affidavit so delivered as aforesaid to have been the Printer or Printers, Proprietor or Proprietors or Publisher or Publishers of such Newspaper or other such Book or Paper as aforesaid after the day on which such last mentioned Affidavit or Affidavits shall have been delivered to the said Justice of Peace as aforesaid.

Article IX: In Newspaper &ca. there shall be printed the names and abode of Printers and Publishers on penalty of Rupees 1000 and proof in manner herein mentioned that the party is the Printer &ca. shall be sufficient unless proved to the contrary

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, that in some part of every Newspaper Magazine Register Pamphlet or other printed Book or Paper as aforesaid there shall be printed the true and real name and names addition and additions and place and places of abode of the Printer and Printers and Publisher and Publishers, of the same and also a true description of the place where the same is printed and in case any person or persons shall knowingly and wilfully print or publish or cause to be printed or published any such Newspaper or other printed Book or Paper as aforesaid not containing the particulars aforesaid and every of them every such person shall forfeit the sum of Rupees One thousand: and that proof made in manner herein mentioned in any proceeding to recover the same that the party proceeded against is a Printer or Publisher of a Newspaper or other such printed Book or Paper so printed or published as aforesaid shall be deemed and taken to be proof that such party is a person wilfully and knowingly printing or publishing or causing the same to be printed or published unless he shall satisfactorily prove the contrary.

Article X: After production of Affidavit or Copy &ca. Newspaper &ca. instituted as therein mentioned &ca. it shall not be necessary to prove the purchase of the same at the house or shop of Defendants

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That it shall not be necessary after any such Affidavit or Affidavits or a certified Copy thereof shall have been produced in evidence as aforesaid against the person or persons who signed and made the same or are therein named according to this Rule Ordinance and Regulation or any of them, and after a Newspaper or other such printed Book or Paper as aforesaid shall be produced in evidence entitled in the same manner as the Newspaper or other such printed Book or Paper mentioned in such Affidavit is entitled and wherein the name or names of the printer and publisher or printers and publishers and the place of printing shall be the same as the name or names of the printer or printers or publisher and publishers and place of printing mentioned in such Affidavit or Affidavits, for any Plaintiff Informant or Prosecutor or person seeking to recover any of the penalties raised by this Regulation to prove that the Newspaper or other printed Book or Paper to which such trial relates was purchased at any house shop or office belonging to or occupied by the Defendant, or Defendants or any of them, or by his or other servants or workmen or when he or they by themselves or by their servants or workmen usually carry on the business of printing or publishing such Newspaper or other printed Book or Paper as aforesaid, or where the same is usually sold.

Article XI: Service at the Printing House mentioned in the Affidavit to be deemed sufficient notice to all persons named therein. But if any person shall have delivered previous to the publication of the Newspaper &ca. to which the proceedings relate an Affidavit that he has ceased to be Printer &ca. he shall not be so deemed after such delivery.

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That service at the house or place mentioned in such Affidavit or Affidavits as aforesaid as the house or place at which such Newspaper or other such printed Book or Paper as aforesaid to which any proceedings, Civil or Criminal shall relate, is printed or published or intended so to be of any legal notice, Summons subpoena rule order or process of what nature soever or to enforce an appearance in any suit prosecution or proceeding Civil or Criminal against any Printer Publisher or Proprietor of any such Newspaper or other printed book or paper shall, be deemed and taken to be good and sufficient service thereof respectively against all persons named in such Affidavit or Affidavits as the Proprietor or Proprietors Publisher or Publishers or Printer or Printers of the Newspaper or other printed book or paper mentioned in such Affidavit or Affidavits. Provided always, That if any such person or persons respectively as aforesaid shall have signed sworn and delivered to the said Justice of the Peace as aforesaid previous to the day of the date or publication of the Newspaper or other such printed Book or Paper as aforesaid to which the proceeding in Court shall relate an Affidavit or Affidavits that he she or they have ceased to be the Printer or Printers Proprietor or Proprietors Publisher or Publishers of such Newspaper or other such printed Book or Paper as aforesaid, and shall make proof thereof, such person or persons shall not be deemed by reason of any former Affidavit or Affidavits so delivered as aforesaid to have been the Proprietor or Proprietors Printer or Printers Publisher or Publishers of the same after the day on which such last mentioned Affidavit or Affidavits shall have been delivered to the said Justice of the Peace as aforesaid.

Article XII: Certified copies of Affidavits to be delivered on payment of

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That the Justice of the Peace by whom such Affidavits shall be kept according to the directions of this Rule Ordinance and Regulation shall, and he is hereby required upon application made to him by any Person or Persons requiring a Copy certified according to this Rule Ordinance and Regulation of any such Affidavit as aforesaid in order that the same may be produced in any Civil or Criminal proceedings to deliver to the person so applying for the same such certified Copy he or they paying for the same the sum of 1 Rupee and no more.

Article XIII: Copies of Affidavits Certified by the Justice of the Peace in whose custody they shall be, to be sufficient evidence

And whereas in many cases it may be productive of public inconvenience to require that the Justice of the Peace before whom such Affidavits as are hereinbefore mentioned are made, should be required personally to attend in order to prove upon the trial of any action prosecution suit indictment information, or in any other legal proceeding that the parties signing swearing and delivering such Affidavit or Affidavits, did swear the same in the presence of, and did deliver the same to such Justice of the Peace before and to whom the same shall have been sworn or delivered respectively; Be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid That in all cases a Copy of any such Affidavit certified to be a true Copy under the hand of such Justice of the Peace in whose possession the same shall be, shall upon proof made that such Certificates have been signed by the hand writing of the person making the same and whom it shall not be necessary to prove to be a Justice of the Peace, be received in evidence as sufficient proof of such Affidavit, and that the same was duly sworn and of the contents thereof, and such copies so produced and certified shall also be received as Evidence that the Affidavits of which they purport to be Copies, have been sworn according to this Rule Ordinance and Regulation and shall have the same effect for the purposes of evidence to all intents whatsoever as if the original Affidavit or Affidavits of which the copies so produced and certified shall purport to be Copies had been produced in Evidence and been proved to have been so duly Certified and sworn by the person or persons appearing by such Copy to have sworn the same as aforesaid.

Article XIV: Penalty of Rupees 1000 on unauthorized Persons giving Certificates

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That if any person not being such Justice of the Peace as aforesaid shall give any such certificate as aforesaid or shall presume to certify any of the matters or things by this Rule Ordinance and Regulation directed to be certified by such Justice of the Peace as aforesaid or which such Justice of the Peace as aforesaid is hereby empowered or entrusted to certify he shall forfeit and lose the Sum of One thousand Rupees.

Article XV: Penalty of Rupees 1000 for falsely certifying that Affidavits were sworn to, or that false Copies are true, &ca.

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid. That if any person shall knowingly and wilfully falsely certify under his hand that any such Affidavit as is required to be made by this Rule Ordinance and Regulation was duly signed and sworn before him the same not having been so sworn or signed or shall knowingly and willfully falsely certify that any Copy or Copies of any Affidavit or Affidavits is or are a true Copy or Copies of the Affidavit or Affidavits of which the same are certified to be such copy or Copies or shall knowingly and wilfully falsely certify or express in any certificate that the Affidavit or Affidavits of which any Copy or Copies arc certified to be a true Copy or copies was or were duly sworn before the person so certifying by the party or parties whose name or names appear subscribed to the same as the name or names of the party or parties swearing and signing the same every person so offending shall in each and every such case respectively forfeit and lose the sum of one thousand Rupees.

Article XVI: After 34 days after the date of Registry a Copy of every Newspaper &ca. to be delivered within 6 days of its publication lo Ike Justice or his Officer on penalty of Rs. 1000. The Paper to be paid for, by the Justice, and may within two years after publication be produced as Evidence in any proceeding civil or criminal

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That from and after fourteen days after Registry and Publication of the Rule Ordinance and Regulation in the Supreme Court as aforesaid, the Printer or Publisher of every Newspaper or other such printed Book or Paper as hereinbefore described shall upon every day upon which the same shall be published, or within six days after delivery to the Justice of Peace before whom the Affidavit as hereinbefore required is made, or to some officer to be appointed by him to receive the same and whom he is hereby required to appoint for that purpose one of the Newspaper or other printed Books or Papers herein before described so published upon each such day signed by the printer or publisher thereof in his handwriting with his name and place of abode and the same shall be carefully kept by the said Justice of the Peace or such Officer as aforesaid in such manner as the said Justice of the Peace shall direct and such Printer or Publisher shall be entitled to demand and receive from the said Justice of the Peace or such Officer once in every six days of publication the amount of the ordinary price of the respective Newspaper or other printed books or papers so delivered and in every ease in which the printer and publisher of such Newspaper or other such printed book or paper as af ore-aid shall neglect to deliver one such Newspaper or other printed book or paper in the manner hereinbefore directed such printer and publisher shall for every such neglect respectively forfeit and lose the sum of One thousand Rupees and in case any person or persons shall make application to the said Justice of the Peace or such Officer as aforesaid, in order that such Newspaper or other printed book or paper so signed by the printer or publisher may be produced in Evidence in any proceeding Civil or criminal the said Justice of the Peace or such Officer shall, at the expense of the party applying at any time within two years from the publication thereof either cause the same to be produced in the Court in which the same is required to be produced and at the time when the same is required to be produced or shall deliver the same to the party applying for it taking according to his discretion, reasonable security at his expense for the returning the same to the said Justice of the Peace or such Officer, and in case by reason that the same shall have been previously required by any other person to be produced in any Court or hath been previously delivered to any other person for the like purpose the same cannot be produced at the time required, or be delivered according to such application in such case the said Justice of the Peace or such his Officer shall cause the same to be produced, or shall deliver the same as soon as they are enabled so to do.

Article XVII: Printers shall give notice in the form annexed No. 1 to the Chief Secretary of Government who shall grant a Certificate in the form annexed No. 2 and file the notice. Penalty of Rs. 400 for keeping presses or types without notice or using them in any place not expressed therein.

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That from and after fourteen days after the Registry and Publication of this Rule Ordinance and Regulation in the Supreme Court as aforesaid every person having any printing press, or types for printing within the Presidency of Bombay shall cause a notice thereof signed in the presence of and attested by one witness, to be delivered to the Chief Secretary of Government for the time being or other person acting and officiating as such, according to the form hereinafter prescribed and such Chief Secretary or other person acting and officiating as such shall, and he is hereby authorized and required to grant a certificate in the form hereinafter prescribed and shall file such notice and every person who, not having delivered such notice, and obtained such Certificate as aforesaid, shall, from and after the expiration of fourteen days next after such Registry and Publication of this Rule Ordinance and Regulation as aforesaid keep or use any printing press or types for printing, or having delivered such notice and obtained such certificate, as aforesaid shall use any printing press or types for printing in any other place than the place expressed in such notice shall forfeit and lose the sum of four hundred Rupees.

Article XVIII: The name and abode of the Printer shall be printed on every paper or book. Printer omitting so to do and persons dispersing papers without such Name and place of abode shall forfeit Rupees 400.

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That from and after fourteen days after the Registry and Publication of this Rule Ordinance and Regulation as aforesaid every person who shall print any paper or book whatsoever within the Presidency of Bombay not being intended to be published periodically but which shall be meant and intended to be published or dispersed whether the same shall be sold or given away shall print upon the front of every such paper, if the same shall be printed on one side only and upon the first and last leaves of every such last mentioned paper or book which shall consist of more than one leaf in legible characters his or her name, and the name of his or her dwelling house or usual place of abode, and every person who shall omit so to print his name and place of abode on every such last mentioned paper or book printed by him and also every person who shall publish or disperse, or assist in publishing or dispersing either gratis or for money any such last mentioned printed paper or book, which shall have been printed after the time hereinbefore last specified and on which the name and place of abode of the person printing the same shall not be printed as aforesaid, shall for every Copy of such paper so published or dispersed by him, forfeit and pay the sum of Four hundred Rupees.

Article XIX: Printers shall keep a Copy of every book and paper they print and write thereon the name and abode of their employer. Penalty of Rs. 400 for neglect or refusing to produce the Copy within 6 months

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That every person who from, and after the time hereinbefore last specified shall print any such last mentioned book or paper whatsoever within the Presidency of Bombay for Hire Reward Gain or Profit shall carefully preserve and keep one copy (at least) of every such last mentioned book or paper so printed by him or her on which he or she shall write or cause to be written or printed in fair and legible characters, the name and place of abode of the person or persons by whom he or she shall be employed to print the same and every person printing any such last mentioned book or paper whatsoever for Hire, Reward, Gain or Profit who shall omit or neglect to write or cause to be written or printed as aforesaid, the name and place of abode of his or her employer on one of such last mentioned printed books or papers, or to keep or preserve the same for the space of six Calendar Months next after the printing thereof, or to produce and shew the same to any Justice of the Peace acting within the Presidency of Bombay who within the said space of six Calendar Months shall require to see the same shall for every such omission neglect or refusal forfeit and lose the sum of 400 rupees.

Article XX: A Justice may empower a Peace Officer to search for Presses and Types he suspects to be illegally used and seize them and the printed papers found

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid, That if any Justice of the Peace acting within the Presidency of Bombay, shall from Information upon oath, have reason to suspect that any printing press or types for printing is or are used or kept for use without notice given and certificate obtained as required by this Rule Ordinance and Regulation, or in any place not included in such Notice and Certificate, it shall be lawful for such Justice by warrant to direct authorize and empower any of his Officers in the day time with such person or persons as shall be called to his assistance to enter into any such house, room and place and search for any printing press or types for printing and it shall be lawful for every such Peace Officer with such assistance as aforesaid, to enter into such house room or place in the daytime accordingly and to seize take and carry away every printing press found therein together with all the types and other articles thereto belonging and used in printing and all printed papers found in such house room or place.

Article XXI: How penalties are to be recovered and disposed of.

And be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid that all offences committed and all pecuniary forfeitures and penalties had or incurred under or against this Rule Ordinance and Regulation shall and may be heard and adjudged and determined by two or more of the Justices of the Peace acting within the Presidency of Bombay who are hereby empowered and authorized to hear and determine the same and to issue their summons or warrant for bringing the party or parties complained of, before them and upon his or their appearance or contempt and default to hear the parties examine witnesses, and to give Judgment or Sentence according as in and by this Rule Ordinance and Regulation is ordained and directed and to award and issue out warrants under their hands and seals for the paying of such forfeitures and penalties as may be imposed upon the goods and chattels of the offender and to cause sale to be made of the goods and chattels if they shall not be redeemed within six days rendering to the party the overplus if any be after deducting the amount of such forfeiture or penalty and the costs and charges attending the levying thereof, and in case sufficient distress shall not be found and such forfeitures and penalties shall not be forthwith paid, it shall and may be lawful for such Justices of the Peace and they are hereby authorized and required by warrant or warrants under their hands and seals to cause such offender or offenders to be committed to the common gaol of Bombay there to remain for any time not exceeding four Calendar Months unless such forfeitures and penalties and all reasonable charges shall be sooner paid and satisfied, and that all the said forfeitures when paid or levied shall be from time to time paid into the Treasury of the United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies and to be employed and disposed of according to the order and directions of —

Article XXII: This Rule Ordinance and Regulation not to extend to certain Publications

Provided always and be it further ordained by the authority aforesaid that nothing in this Rule Ordinance and Regulation contained shall be deemed or taken to extend or apply to any book or paper printed by the authority and for the use of the Government of any or either of the three Presidencies of India, or to any printed book or paper containing only Shipping Intelligence, Advertisements of Sales, Current prices of Commodities, rates of Exchange or other Intelligence solely of a commercial nature.

No. 1: Form of Notice to the Chief Secretary or other person acting as such that any person keeps any printing press or types for printing

I A.B. of ______ do hereby declare [illegible] types for printing which I propose to use for [illegible] Bombay, and which I require to be entered for that purpose in Pursuance of the Rule Ordinance and Regulation No. ______ of 1825.

"Witness my hand this day of ______. Signed in the presence of ______.

A.B.

No. 2. Form of Certificate that Notice has been given of a printing press or types for printing.

I CD. Chief Secretary to Government (or acting Chief Secretary) do hereby certify that A.B. of ______ hath delivered to me a notice in writing appearing to be signed by him and attested by ______ as a witness to his signing the same that he the said A.B. hath a printing press and types for printing which he proposes to use for printing within the Presidency of Bombay and which he has required to be entered pursuant to the Rule Ordinance and Regulation _____ of 1825.

Witness my hand this ______ day of ______.

CD.

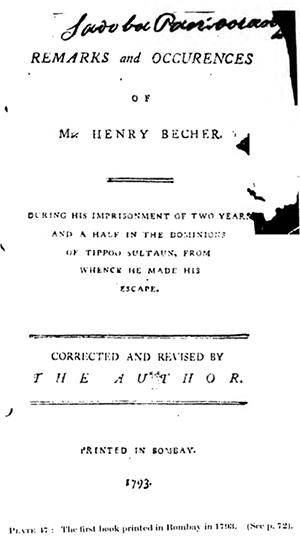

The Printing Press in India, by Anant Kakba Priolkar

21 posts

• Page 2 of 3 • 1, 2, 3

Re: The Printing Press in India, by Anant Kakba Priolkar

Part 1 of 4

Part II : AN HISTORICAL ESSAY ON THE KONKANI LANGUAGE

A LIFE SKETCH OF J. H. da CUNHA RIVARA* [* The author of the Historical Essay on the Konkani Language.]

JOAQUIM HELIODORO da CUNHA RIVARA was a well- known writer and scholar. He was born in Arraiolos, 23rd June 1800, and died in Evora on the 20th February 1879. His father was Dr. Antonio Francisco Rivara, Genooese by nationality and his mother, D. Maria Isabel da Cunha Feio Castelo Branco, Spanish by nationality. Having gone through the preparatory courses in Evora, he entered the University of Coimbra in the year 1824, but had to break off when he had completed the 3rd year of Medicine in 1828, as the University had to close down owing to the political events of the time.

J. H. da CUNHA RIVARA

During the civil war he withdrew to his home, and it was only at the end of the war in 1834 that he could resume his studies and take the degree in 1836. However, he did not show great inclination to practise Medicine. After holding for some time the post of the First Official in the Civil Secretariat of Evora, he took charge of the chair of rational and moral Philosophy in the Lyceum of the same city (Decree of 27-7-1837), holding simultaneously the post of librarian of the Library of Evora (25-12-1838). During fifteen years he put forth considerable effort in re-organising the Library which had suffered complete decay. The political agitations and crisis of those years were a source of immense difficulties, as the Government could hardly pay attention to cultural or pedagogical matters. He succeeded, however, in putting up a new hall to house 8,000 volumes, and in completely overhauling the whole building; and after laborious investigations he selected and incorporated in the Library over 10,000 volumes from the libraries of extinct convents, besides donating 182 volumes of old, and mostly rare works from his own private library.

All the above books were catalogued by him, as he had no assistant. His attention was specially drawn to a valuable collection of manuscripts, mostly Portuguese, referring to Asia, Africa and America, of which he made an inventory and catalogue, and with these he prepared and printed a large size volume in 1850.

Cunha Rivara gave valuable help to Count Raczyuski in his art investigations, which this foreign savant acknowledged in his book. This exhausting activity did not stand in the way of his teaching work which he carried out with equal solicitude, or of his constant collaboration in the journals and reviews of the time. He co-operated in the Publication of Reflexoes sobre a Lingoa Portugueza, by Fr. Francisco Jose Freira (Edited by Sociedade Propagadora dos Conhecimentos Uteis, Lisbon, 1842), of which a new edition was brought out later with a masterly preface by Rivara.

As he had always kept aloof from political struggles, there was general surprise that he should have stood up for election as a deputy for Evora in 1853, an election which he won. In the Chamber of Deputies he took particular interest in questions of administration and education. He was a member of important Committees, among others of the Committee of Inquiry on the Bank of Portugal.

The Viscount, later Count, of Torres Novas, on his appointment as Governor General of India, selected him as General Secretary, and he was nominated to this office on June 3rd, 1855. During the tenure of this office which lasted till 1870, Cunha Rivara enjoyed the confidence of all Governors, and made a conspicuous contribution to the improvement of administrative services, public instruction, and people's education as well as to economic and industrial progress. Charged with the definition of areas of the dioceses of India within the jurisdiction of the "Padroado" of the East as per Concordat of February 21, 1857, Cunha Rivara proved a stalwart champion of the rights of the Portuguese nation, whether in official negotiations or in polemics in the press and pamphlets, in which he vigorously argued against the excessive claims of the Vicars Apostolic. In 1858 the metropolitan Government appointed him to continue the historical work of Joao de Barros and Diogo do Couto on the conquests and the domains of Portugal in Asia. Without availing himself of the offer of official allowances, he visited the whole coast from Diu to Cape Comorin, that of Malabar and Coromandel, in a tireless investigation of all ruins and monuments which gave evidence of Portuguese activity. With the same meticulous care he examined the numerous documents in the Archives of India, and published them in the Boletim Official, the Cronista de Tissuary, and other periodicals, as well as in special volumes and booklets. He resigned in 1870, but continued in India till 1877, carrying on his historical studies. His stay in Lisbon was brief. He spent the remainder of his life in Evora.

Throughout his life he developed an intense intellectual activity. Thus in the Review Panorama he published numerous articles from 1838 to 1854, among which were chapters of Memorias da Vila de Arraiolos, which corrected and enlarged, he intended to publish in a complete work, but the scheme was not carried out. From 1859 to 1861 he was a frequent contributor to the Arquivo Universal of Lisbon, where in Vol. III, pp. 289-291 he published a remarkable note on Deducao Cronologica vertida em Chines (Chronological Deduction turned into Chinese). In the monthly O Cronista de Tissuary which he edited and which began its publication in Nova-Goa (Pangim) in Jan. 1866 and ended in June 1869 (4 vol.), he published numerous documents on Portuguese activity in Asia, and, often anonymously — in view of his official position, articles in defence of Portuguese interests in the "Padroado" of the East. In the Boletim do Governo da India he published his more important articles on the same question. His collaboration in this Boletim went on from 1855 to 1875. His contributions also appeared in Revista Universal Lisbonense; Aurora de Lisboa; Revista Literaria, Porto; Journal da Farmacia e Ciencias Medicas of Portuguese India, 1862 and 1863; Arquivo da Farmacia, idem 1864-1871, Instituto Vasco da Gama, idem 1872-74; and Imprensa de Ribandar, 1870-1871. In the Arquivo Portugues Oriental which was published in Panjim in 1857-76 he brought out with a commentary of his own, a volume containing letters which the Kings of Portugal had addressed to the Cidade de Goa (Corporation of Goa); the letters of instructions of the Kings of Portugal to the Viceroys and Governors of India in the 16th century as well as executive orders, decrees etc., of the time; the letters ad- dressed to the ecclesiastical council of Goa and the Synod of Diamper; various documents of the 16th and 17th centuries etc. He wrote introductions or annotations to Gramatica da Lingua Concani by Fr. Thomas Stevens, with additions by other Fathers of the Society of Jesus, with an introduction consisting of a Memoir on the geographical distribution of the main languages of India by Sir Erskine Perry, and of the Ensaio Historico da Lingua Concani, Noa-Goa, 1857. Grammatica da Lingua Concani no dialecto do Norte, work of a Portuguese missionary of 17th century, now published for the first time Nova-Goa, 1858; Gramatica da lingua Concani written in Portuguese by an Italian missionary, Nova-Goa, 1859; Diccionario portugues-concani, by an Italian Missionary, Nova-Goa, 1868; Letters of Luis Antonio Verney and Antonio Pereira de Figueiredo to the Fathers of the Congregation of the Oratory of Goa, Nova-Goa, 1858; Memorias sobre as possessees portuguesas na Asia, written in 1623 by Goncalo de Magalhaes Teixeira Pinto, High Court Judge, now published with brief additions and annotations, Nova-Goa 1859; Demonstratio juris patronatus Portugaliae Regum (Defence of the Padroado) composed by the Archbishop of Braga, D. Ludovico de Souza, written at the instance of the Prince Regent of Portugal during the Pontificate of Innocent XI, 1677, a work now brought to light by Cunha Rivara, Nova-Goa, 1880, and this was based on a codex of the Evora Library which he believed to be either the autograph or a contemporary copy. Descrigao dos Bios de Sena by Francisco de Melo de Castro, Nova-Goa, 1861; Observacoes sobre a historia natural de Goa, made in 1784 by Manoel Galvao da Silva and now published, Nova-Goa 1862; Documentos on the occupation of the Bay of Lourenco-Marques, East Coast of Africa, attempted or carried in the first half of the 18th century by some nations of Europe, specially the Dutch, found in the Government archives, Nova-Goa, 1873.

Cunha Rivara was a Fellow of the Academy of Sciences, the Historical and Geographical Institute of Brazil, and other scientific and literary societies. He was honoured with Comenda of the Order of Villa Vicosa (Decree of 4-6-1860) and that of the Order of Santiago (Decree of 14-4-1860) and was granted the title of Concelheiro (Councillor), Decree of 11-3-1861.

He was the author of: Apontamentos sobre os Oradores parlamentares de 1853, Lisboa, 1853; De Lisboa a Goa pelo Meditarraneo, Egipto e Mar vermelho (Description of voyage from Lisbon to Goa); A Circular Letter addressed to his friends in Europe, Nova-Goa, 1858; Viagem de Francisco Pyrard de Laval (report of his voyage to East Indies, the Maldives, Molucca, Brazil, 1601-11) translated from French edition of 1679, with corrections and notes, Nova-Goa, Vol. I 1858, Vol. II 1862; Analysis of a pamphlet "O Visconde de Torres Novas e as Eleicoes em Goa" printed in Lisbon, 1861, anonymously, Nova-Goa, 1862; Address to the Electors (on the candidatures to the Chamber of Deputies of Bernado Francisco da Costa and Antonio Augusto Teixeira de Vasconcelos) published anonymously, Nova-Goa, 1865. Ensaio Historico da lingua Concani, Nova-Goa, 1858; Memoria sobre a propagagao e cultura das chinchonas medicinaes by W. Graham, translated from English, Nova-Goa, 1864; Inscricoes de Dio, Nova-Goa, 1865.

(Translated from the Grande Enciclopedia Portuguesa e Brazileira — Vol. 25, Lisboa, pp. 791-793).

TRANSLATOR'S NOTE

FEW scholars have done more to promote the cause of the native language of Goa than J. H. da Cunha Rivara, the Portuguese savant of the 19th century.

Both the Konkani speaking people and students of the history of Indian languages will be forever indebted to him for his historical essay on the language and the printing of its grammars.

I have confined myself in this book to the translation into English of his epoch-making Ensaio Historico da Lingua Concani published in Nova Goa in 1858.

In the body of his work, Cunha Rivara has listed elaborate documents or historical data in support of many of his statements as to the origin and vitality of the language as well as the many vissicitudes through which it had to pass in its long and chequered career.

It was not possible in my translation to include these records owing to their bulk. The book, however, contains footnotes both mine (marked with asterisks) and those of the author to elucidate certain points in the text of the translation.

In writing a book of this nature, the translator has naturally to labour under many difficulties. The Portuguese in which the original essay was written 100 years ago and the language of the documents which goes further back in time is archaic and requires studious examination.

I have, however, tried to follow the original text closely, retaining as far as possible the author's trend of thought and his interpretation of contemporary conditions. I am greatly indebted to Principal Aloysius Soares; and Prof. A. K. Priolkar, Director of Marathi Research Institute, who gave me invaluable help in reading the text as well in the elucidation of certain passages in the essay.

It is therefore with great pleasure that I submit my translation of the Ensaio Historico da Lingua Concani by Cunha Rivara, on the occasion of the centenary of its publication.

THEOPHILUS LOBO

AN HISTORICAL ESSAY ON THE KONKANI LANGUAGE

I

THE attempt on our part to write an Historical Essay on the Konkani Language could justifiably be considered as presumptuous, if someone competent to undertake this arduous task could be found among those who knew the mother- tongue. On one occasion in the past we have drawn attention 1 [Lecture delivered at the opening of the Primary Training School of Nova Goa on the 1st of October 1856 — Boletim do Governo, No. 78.] of the public to the unique phenomenon of ignorance regarding the structure and grammatical forms of the mother-tongue which has prevailed in Goa from remote times. We have also pointed out the absurdity of the affirmation that a language spoken by half a million of people had no grammar and was not even capable of being set in writing. We, therefore, thought that we would be of some use if we could dissipate such a pernicious impression and illusion and prove that the Konkani language possessed not only grammar like other languages, but a grammar which, from ancient times, was appropriately formulated in rules and actually printed. And if the Portuguese and the natives despised and persecuted it, it has, nevertheless, received the attention of learned foreign orientalists, who to the great benefit of science and the good of humanity have been applying themselves to the study of Indian languages.

In spite of the great impulse which the language received in the first century of Portuguese dominion, there rose against the language an implacable war with attempts to entirely extinguish and proscribe it. Although it was not possible to achieve the end fully, as it is beyond human power to suppress a language, it has, however, been corrupted and adulterated and its literary records practically destroyed to the serious loss both to the intellectual and moral culture of the people.

The author, acknowledging his lack of competence, therefore, limits himself partly to compile what those well-versed in this language have said and have ascertained; and partly, in the light of authentic documents, government circulars and other facts to arrive at a conclusion as to what has influenced its progress or decadence.

II

In the first part of this introduction, namely, the Paper on the geographical distribution of the principal languages in India, 2 [Sir Erskine Perry, The Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. January 1853. The Portuguese translation of this paper was published with the first edition of this Essay.] we have seen how the Konkani language hails from the family of Sanskritic languages, or those of the north. Authors with considered views on the subject regard the language as the daughter, or more appropriately, the sister of Marathi, though those living around the coast of Kanara consider the language to be completely different from Marathi. This view, however, may be rejected, due to palpable and decisive analogies existing between Konkani and Marathi. The weighty authority of Murphy, 3 [Robert Xavier Murphy (1803-1857) Editor of Bombay Gazette, 1834; Oriental translator to Government of Bombay 1852; a classical scholar and quick at acquiring of Oriental languages; wrote largely on Oriental subjects philosophical and literary, antiquaries, etc.] quoted by the author of the above-mentioned Paper on the study of the grammar of Konkani proves abundantly that its grammar is the same as that of the Marathi language. The nouns and verbs are declined in the same way, with minor modifications of little significance. According to the same authority, Konkani does explain some difficulties inherent in the Marathi language. What are considered as anomalies, or defective voices in the latter, are sometimes accepted as rules, and in a complete form in the former. Finally, it appears that Konkani is the very Marathi language with a large admixture of Tulu and Kanarese words; the former derived from the native inhabitants of Tuluva, or Kanara; the latter resulting from the long subjection of this part of Konkan to the Kanarese dynasties above the Ghats.

Konkani language has undergone an unique Brahmanic influence; and as attested by the above-mentioned Murphy, many Sanscritic words, signifying natural objects, have entered into its popular usage. These words are not used in the same sense in any other part of India. Thus the common terms to signify water, tree and grass, are Sanscritic; and pronounced by the Shenvi Brahmins give the sound of udak, uriksh, trin; pronounced by Christians of the place would sound udik, rukh, tan, etc.

Goan experience and tradition testify that this difference in pronunciation is preserved and perpetuated among the Brahmin Christians, and that it is a distinguishing mark of that caste; whilst the Chardes 4

attribute it to affectation and corruption, a view worthy of severe condemnation. 5 [ ]

Again, according to Murphy, the masculine termination o of Gujerati and Marwaree also occurs in Konkani, in place of a used in Hindi and Marathi.

Another contemporary philologist, 6 [Fr. Francis Xavier, Italian Carmelite, Missionary in Canara, Archbishop of Sardes and Vicar Apostolic of Verapoly.] who has studied the language profoundly in Kanara, and also composed a Dictionary and a Konkani-Portuguese Grammar is fully in accord with the opinion of Murphy regarding the genius and disposition of the language. His grammar starts with this note or observation: "Even though the Konkani language, whose grammar I am writing, be different from the Marathi language, it has great similarity with the other, which we may even call natural; besides the Konkani language has adopted from Marathi some words and phrases it did not have; and as Greek vocables assimilated in Latin language are called Grecisms, so the adaptation of Marathi words by the Konkani language may be called Marathisms."

III

The name concani, concanica, or concana is derived from the territory (Konkan) where this language is commonly spoken. The Portuguese missionaries who were the first to cultivate it intensively during the 16th and 17th centuries, commonly called the language the Bramana language, Canarim 7* [It appears that the term Canarim (Persian word for "coaster") was first given by the Arab-traders to the people on the Malabar Coast which was subsequently adopted by the Portuguese and applied to the native Christians of Goa.] language or Canarina. The first name clearly arises from the fact that the Brahmins, alone among the Hindus, knew to read and write in that language; the second name Canarins, is given by the Portuguese to the natives of Konkan, which extends even beyond the limits of Kanara. Therefore, it is necessary to bear in mind, that this language is not the same as the one known as Kanara or Canarese, spoken by the people of Kanara and other provinces, which as we have already seen in the paper of Sir Erskine Perry, really belongs to the Tamilian family.

The Konkani language starts from the north of Goa in the southern districts of the British Collectorate of Ratnagiri, where it meets the Marathi language; and towards the south it extends up to Udipi in the proximity of Kundapur, in Kanara, or according to another view, up to Mangalore, where the commonly spoken language in that place, Tulu, has its beginning. Thus, Konkani is more a southern branch of the Sanscritic or northern family, uniting this family with the Tamilian or southern branch. Towards the east it extends up to the Ghats; in addition, it is spoken by various castes in Bombay and in the whole island of Salsette — principally by the Christians.

Konkani cannot be exclusively called the language of all the classes of people who live in the provinces, where it is spoken. Thus, for instance, it is not spoken by all the people of Kanara, who speak both Tulu and Marathi, whereas in Sawantwadi it has equal footing with Marathi, Urdu and Hindustani.

According to the present Political Superintendent of Sawantwadi, 8 [Brief Notes relative to the Sawantwaree State submitted to Government on the 1st July, 1854, in the selections from the Records of the Bombay Government, Xo. X, New Series.] Major J. W. Auld, three languages are spoken in that State. The Muslims speak Hindustani or Urdu, high class Hindus speak Marathi, and other inferior castes speak a corrupt form of Marathi, known as Kuddali, which is more in vogue in the southern districts of the Collectorate of Ratnagiri. This corrupted form of Marathi, referred to by Mr. Auld, is the true Konkani language. This language which carries with it an abundant mixture of Portuguese words is the people's language in the Portuguese territory as well as in Sawantwadi and other districts.

Later on, we shall have occasion to deal with the causes that have brought the Konkani language to the state of corruption at present prevalent in Portuguese territory, chiefly in the provinces constituting the Velhas Conquistas. 9* [The districts conquered or acquired by the Portuguese in the beginning, viz. Goa Islands (1510), Bardez and Salsete (1543).] The views of a few modern authors are given below: —

The Rev. Luiz Cottineau de Kloguen who visited Goa about the year 1829 says: — " All speak a corrupt dialect, a resultant of Portuguese Konkani and Marathi languages, which, however, has been reduced to grammatical rules. The poor and those who cannot read, chiefly the women folk, speak this language only." 10 [An Historical Sketch of Goa, Madras 1831, p. 107.]

Manoel Felicissimo Louzada de Araujo e Azevedo, who lived in Goa (1827 to 1837) writes: "In addition to the Portuguese language, the people speak the local language, which is a mixture of Kanarese and Marathi. The Hindus in their writings commonly use the Tndo, Kanarese or Marathi dialects, and several scripts. Those from the Provinces of the Novas Conquistas 11 [The Districts newly acquired by the Portuguese. They are: Sanguem, Quepem and Canacona in 1761; Ponda in 1763; Pernem and Sanquelim in 1782 and Satari in 1778.] write as rapidly as they speak, but very few among the Hindus can write these dialects without getting mixed with other dialects." 12 [Segunda Memoria descriptiva, e estatistica das Possessoes Portuguezas na Asia: nos Annaes Maritimos e Coloniaes, anno 1842, p. 50.] Felipe Nery Xavier says: "In their dealings in general and familiar intercourse, the language commonly used by the people is a combination of the Marathi and the Kanarese languages with the local dialects in each of the Districts and Provinces; the same holds good of each class or caste. In their writings, however, they make use of Portuguese dialect and among themselves the Hindus use Kanarese, Hindi or Marathi in adulterated form: yet very few use one form without mixing it with the others." 13 ["Nocao Historica de Goa," Gabinete Litterario das Fontainhas, Tom I. 1846, p. 43.]

The language is purer in the Novas Conquistas; and its chance of being corrupted lessens in proportion to the distance from the territory of Goa.

IV

The Konkani literature, chiefly religious, owes its existence exclusively to the Portuguese missionaries. The Rev. J. Murray Mitchell the noted Protestant missionary, and learned Orientalist of the Bombay Presidency, published in 1849 one Paper 14 ["Marathi Works composed by the Portuguese," The Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bombay. No. XII, Vol. III, January, pp. 132-157.] on this literature, the language of which he called Maratha; and under this misconception he exerted himself to find out, and did discover innumerable mistakes of all kinds, both as to the use of vowels as well of aspiration and other grammatical points, from whence he concluded that this Marathi language has been falsified, adulterated, corrupted and brought low. 15 [Ibid., p. 136 and Philipe Xery Pires; Grammatica Maratha explicada em Lingua Portugueza, Bombay, 1854, p., 103.]

We beg leave from the learned British Orientalist, and Mr. Filipe Nery Pires, who appears to hold the same view 16 [Philipe Xery Pires, Op. cit...., Preface, p. XIV.], to say that we feel that there is a serious error in such censure. Filipe Nery Pires himself (and his authority in this matter cannot be questioned, because he is both a son of Goa, as well as an eminent professor of Marathi) agrees with the opinion of Murphy in that the Konkani language, Bramana, or Canarim (as ancient Portuguese authors called it) has very close analogy with Marathi: "The declensions of its nouns (says he) together with its terminations and inflexions, affixes, suffixes and prefixes; pronouns personal, relative and possessive, terminations and conjugations of its verbs; its auxiliaries, prepositions, adverbs, conjunctions, and interjections; finally the syntax, and all the rules by means which the structure of this dialect is composed and regulated; in a word, the whole mechanism is identically the same as in this Compendium (of Marathi Grammar)." 17 [Ibid.] But this is not sufficient to conclude that both the languages, Marathi and Konkani, are one in the same way as one cannot confound Spanish with Portuguese.

And thus it appears to us that Fr. Francis Xavier and Murphy were on surer ground, when they considered these two languages to be distinct, than Rev. Cottineau de Kloguen and Murray Mitchell who identify them. The latter fell into the error into which, for instance, a Russian or German might fall, who after having studied the Spanish language and casually seeing a book written in Portuguese, would catalogue mistakes contained therein, on the persuasion that the book was written by a Spaniard who had blundered through ignorance of his own language. The critic, for instance, would have noticed two errors in the word coracao, namely, c in place of z and ao in place of on, whereas in Spanish the word is written corazon. Similarly the word chorar would constitute a very grave error, for the Spanish language has ll for ch of Portuguese, and hence the word is written llorar, etc.

Rev. Murray Mitchell, however, may be excused to a certain extent. His Paper does not deal with the Portuguese-Konkani literature ex professo. It only contains certain observations, which according to him, might lead to the investigation of an interesting and important subject. 18 [Murray Mitchell, Op. Cit., p. 133.] We believe that the confusion he has created in mixing up the Konkani language with the Marathi resulted from the fact he knew only one ancient Konkani publication (the Puranna of Fr. Francis Vaz de Guimaraes) 19 [This Puranna attributed to Guimaraes was first published in 1845 in Bombay and there were a few subsequent editions.] and probably a minor modern book (Manual de Devocoes) printed in Bombay in 1848; he had also by chance come into possession of the Cathecismo da Doutrina Christa, printed in Rome in the year 1778 by the Press of the Congregation of Propaganda. This was written in Portuguese and Marathi in Roman characters according to the system of the Grammatica Maratha printed at the same press and in the same year. This grammar the Rev. Murray Mitchell, in spite of all his attempts, was unable to find. 20 [Murray Mitchell, op. cit., p. 157.]

Rev. Mitchell finds the language of the Cathecismo more correct than that of the Puranna of Fr. Francis Vaz; and anxious to discover the reason for such a difference, he arrives at this conclusion: "The higher castes of Hindus, in these western parts of India, were not very much impressed with the Roman Catholic religion, those converted being exclusively from the poorer classes cultivators and fishermen; and it is likely that the Marathi dialect of this people may have been adopted by their religious teachers, without any attempt to uplift or to systematize it." 21 [Ibid., p. 136.]

In so far as it has reference to the territory of Goa, this observation is inaccurate since there were abundant conversions among the Brahmins and higher caste people, from whom the Catholic priests learnt the language correctly and systematically. The mistake the Rev. M. Mitchell committed is that he did not consult a greater number of books. Had he done so, he would not have identified both these languages which are distinct — though similar and sister-like.

The misconception of Murray Mitchell is shared by those Marathi speaking individuals to whom he had shown or read a certain old work printed in the Bramana language (Konkani) and who took it to be a book written in Marathi. 22 [Pires, op. cit., Preface, p. XV.]

We say this with great reserve, acknowledging, that we are not competent at all to enter into philological discussions on Oriental languages with the eminent professors to whom we have referred.

Truth demands that we acknowledge that the most ancient book published by our missionaries (the Puranna of Father Thomas Stephens) has been accepted by the censors as written in the Bramana-Maratha language; a description which does not contradict our view, because it may be explicable by the clear knowledge they had of the affiliation of Marathi, and because neither at that time nor later had the experts accepted a special and fixed name for this language of Konkan.

V

Two observations, however, are entirely true. The first is of Mr. Felipe Nery Pires, when he says that the Bramana (Konkani) dialect or language as found printed in old books, differs very much from the one now actually in vogue in Goa, which being corrupted to the highest point of degeneration, cannot be classified among oriental languages. 23 [Ibid., Preface, p. XV.] The second observation is of the Rev. Mitchell who says: "It is evident from all the books that we have seen of Marathi (otherwise Konkani) in Romanized characters, that the Portuguese ecclesiastics never reduced to a system the orthography of Marathi (otherwise Konkani); the same work contains a word spelt in different ways, sometimes in four or five different forms, and each of these words is so confusedly spelt in various books that it can be understood with difficulty. What is patent in these works is the absence of accentuation; and indeed this is the source of much confusion. 24 [Mitchell, op. cit., p. 156; Pires, op. cit., p. 104 (Note).]

Leaving for later discussion the causes of the corruption of Konkani in Goa, we shall make a reference to the observation of the Rev. Mitchell regarding the inconsistency of Konkani-romanized orthography.

In his Marathi Grammar, Felipe Nery Pires, by Romanisation means the method or system in which Roman letters as adopted in European languages are used to represent words of oriental languages. 25 [Pires, op. cit., Preface, p. XI.] The difficulty one would experience in such a method is easily noticed in the diversity of sounds and aspirates the oriental languages have as distinct from those in European languages. This difficulty must have been very great when the Portuguese missionaries attempted to write in Konkani, at the time when carried away by unenlightened zeal, the conquerors had destroyed all records of vernacular literature, thus doing away with the elements necessary to study the languages of the conquered people. This was the reason why a fresh start had to be made, and they had to indulge in guess-work about the nature of the grammar and orthography of these languages. In the course of this work, it was found easier to introduce Romanized words to express Konkani vocables, than for grammarians to adopt the Marathi alphabet, though the latter course would be proper and more natural.

If, therefore, a different system of orthography existed in the Portuguese language in those times, and exists even now, why should there be surprise at the serious difficulties that arose in expressing sounds of such different languages in Portuguese characters? Why should there be surprise that the various authors could not agree in this matter in their first literary attempts, and that the very same authors were not consistent in their own writings?

The Marathi language itself, now studied and cultivated extensively is not free from such difficulties, as is found not only when the Marathi writings of English and other foreign authors are compared with one another, but even in a comparison of the works in Marathi of Portuguese authors themselves.

Mr. Filipe Nery Pires, in his Marathi Grammar, says: "Acknowledging from my personal experience that the different sounds and varied inflexions of Marathi cannot be duly expressed in Roman characters according to the pronunciation and value, which they receive in the Portuguese language without modification, I was compelled to invent a phonetic system which, due to its simplicity, would practically satisfy all the requirements. Those invented by Sir Williams Jones and by Doctor Gilchrist and generally adopted by the English, being peculiar to the language and the pronunciation of their nation, could not evidently be made applicable to the Portuguese language. The Roman alphabet, adapted to English pronunciation, shows such a great variety of sounds, such uncertainty, and such a strange confusion, that one could safely affirm that it is transformed into another and that it does not express, nor articulate the natural sounds proper to other languages. The same vowel has various sounds in various words and many times the sound of vowels is expressed according to their position; for instance the five vowels have twenty-six sounds (see Help — published by the American Mission). It is this variety of sounds for each vowel that occasioned the special necessity of a dictionary of pronunciation. It is needless to add that when writing for the Portuguese, it would not have been proper to model my system on the English; but I had to invent a new one, conformable to the language in which I write. The Roman alphabet adapted to the Portuguese has an enunciation and fixed pronunciation, and the sound whether of vowels or of consonants, is generally invariable and determined. It is only in a few cases that there occurs a slight inflexion; and this can easily be recognized by the use of accents, and other orthographic signs. Not being in possession of any norm or example that could guide me, 26 [It looks as if the Grammatica Maratha e Purtugueza reference to which will be made in course of this essay was not known to Mr. Phelipe Nery Pires.] I have ventured to present my system, which based on Portuguese pronunciation, would need minor modifications to express various sounds of Marathi characters. This necessity, it appears to me, has been satisfactorily met by the use of certain diacritical accents, etc." 27 [Pires, op. cit, Pref. pg. XI.]

VI

In spite of the advantages found by Mr. Filipe Nery Pires in the use of the Roman alphabet, pronounced according to the rules of the Portuguese language, to express Marathi sounds, a comparison of the system adopted by Mr. Pires with the one used by the missionaries, who in the last century (1778) printed in Rome the Portuguese-Marathi Grammar,28 [The Marathi Samshodhana Mandala (Bombay) has acquired a microfilm of this first edition from the Jesuit collection at Gotingen, through Fr. Wicki, S.J.] (reprinted in Lisbon in the year 1805),29 [Grammatica Marastta a mais vulgar que se practica nos reinos do Nizamaxa e Idalxa offerecida aos muito reverendos Padres Missionarios dos, ditos Rienos, printed at Rome at the Sagrada Congregacao de Propaganda Fide 1778 and afterwards in Lisbon at the Royal Press, 1805. By Order. (This book is translated into English and published with an introduction by Prof. A. K. Priolkar in the Journal of the University of Bombay, Vol. XXII, part 2, Sept. 1954).] will reveal such a divergence that it is almost impossible to believe that the two Grammars had the identical intention of explaining to the Portuguese the Marathi language and that too with the claim of Romanizing it with reference to the value of letters (alphabets) and pronunciation of the Portuguese language.

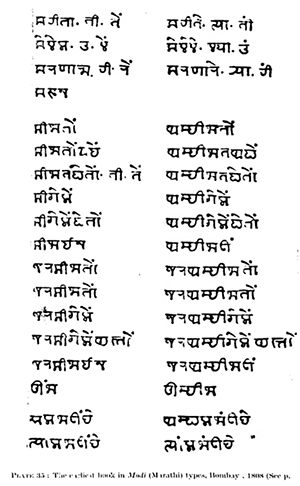

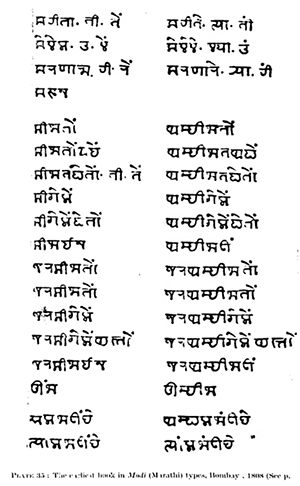

It will be interesting to place before the reader a few examples; I shall select the following at random:

First Example

Present Tense of the Indicative of the Verb 'To Be'.

In view of this we hope that the old Portuguese authors, if not absolved, at least will be, on the whole, excused from the sin of uncertainty in Romanizing the Konkani language, whose natural alphabet is that of Marathi.

VII

We shall now endeavour to investigate the causes which, under the Portuguese regime, were either favourable or contrary to the culture of the Konkani language. In the first ardour of conquest, temples were demolished, all the emblems of the Hindu cult were destroyed, and books written in the vernacular tongue, containing or suspected of containing idolatrous precepts and doctrines, were burnt. There was even the desire to exterminate all that part of the population which could not be quickly converted; this was the desire not only during that period, but there was also at least one person who, after a lapse of two centuries, advised the government, with almost magisterial gravity, to make use of such a policy.30 [Opinion given by Fr. Caetano de S. Joseph, a Dominican friar, in the College of St. Thomas on the 10th of January 1728. Livros das Mooncoes, No. 94, fol. 121.]

India, however, was not America. If in America the European conquerors could in a short time exterminate the indigenous races, primitive or totally savage, and re-people the land with immigrants from Europe, the long distance that separated the Indian conquests from the metropolis, and above all the invincible resistance naturally offered by a numerous population, among whom the principal castes had reached a very high degree of civilization, obliged the conquerors to abstain from open violence, and to prefer indirect though not gentle means, to achieve the same end.

But the very zeal for the propagation of the Christian faith, the needs of the government for the lands conquered, or feudatories, and the necessities of commercial intercourse made evident to the conquerors the great need for the knowledge of vernacular languages, and for securing assistance from the natives, even in the priestly ministry itself.

It was in the year 1541, when already Hindu temples had been demolished in the Island of Goa, and when there were churches, monasteries and parishes in the city, and various chapels outside the city walls, that Fernao Rodrigues de Castel Branco, Administrator of the Treasury and acting Governor, in the absence of Governor D. Estevao da Gama, obtained the consent of the Hindu co-sharers of the communities (gaocares) residing in the same islands to hand over the properties of the temples to His Majesty, for the maintenance of the churches and the Christian clergy. This deed of consent contains a clause proving how the knowledge of the language was thought important for the progress of conversion: "And if in future there should be priests, native to the country, who might be judged competent to be in charge of the chapels, these chapels ought to be given to the same, so that the local people may be satisfied, and more willingly learn from them, both because of the language as also because it was natural."31 [Tombo Geral -- This document has been published (with some inexactness) by Sr. Philipe Nery Xavier in the Bosquejo Historico das Communidades. part II, p. 13. (It is now published in the second edition of the book, revised and enlarged by Sr. Jose Maria de Sa. Vol. I Dec. 7 Bastora 1903, pp. 207-214, as it was printed in the Archivo Portuguez Oriental Fasc. 5, p. 161).]

VIII

It is true that the Bishop, Dr. Fr. Joao de Albuquerque, towards the end of the year 1548, with the intention of ending idolatry,32 [Letter of the above mentioned Bishop. written from Goa on the 28th November, 1548, to His Majesty. It is filed in the Torre de Tombo in Lisbon. (This letter is now published: (1) F. D. D'Ayalla Goa Antiga e Moderna (2nd edition) Nova Goa. 1927, p. 74. (11) A. da Silva Rego, Documentaccao para a Historia das Missoes do Padroado Portugues do Oriente, Lisboa, 1950, pp. 133-4 ).] was busy confiscating literature written by the Hindus; but thereafter the Councils and Goan Constitutions recommended and ordered the use and the study of the language of the land.33 [All the decrees of these Provincial Councils are published in the fourth fascicule of the Archivo Portuguez Oriental edited by Cunha Rivara. Goa 1862.]

The first Provincial Council, held in Goa in the year 1567, states the following in its 5th Decree of the First Act: --

"As (according to the Apostle) fides sit ex auditu, auditus per verbum Christi: the Sacred Council orders that all the Ordinaries should select persons well-versed and zealous for the salvation of souls. In the cities, as well as in other places, where the Hindus live, the appointed priests should preach to the Hindus every Sunday in the Churches most convenient to the latter, pointing out to them their errors and explaining the truth of our Holy Faith in a manner adapted to their understanding, not expounding the highest mysteries of the faith, bearing in mind what the Apostle says: Lac vobis potum dedi, non escam; so that they may easily come to the knowledge of Christ, Redeemer of the world. All the Hindus above the age of fifteen, living in their dioceses should be obliged to hear the preaching. Failure to comply with this ordinance would debar them from communication with the faithful. Since this preaching would be the more fruitful, if the preacher were well versed in the language of those to whom they would preach, the Council very earnestly urges the Prelates that they should have in their dioceses trustworthy persons, who would learn languages, and might be admitted for priesthood, and in turn would busy themselves with the work of preaching and hearing confessions, and imparting the doctrine required for conversion; and request His Majesty to order the Hindus to attend these sermons, imposing on the disobedient suitable punishment."

However extraordinary this Decree of the Council may appear, nevertheless the Viceroy confirmed it at once in the name of His Majesty with certain provisos and limitations in the Law of the 4th of December of the year 1567 which runs thus: "Firstly lists should be made of the names of all the Hindus residents in the parishes of the city, each list in the parish to contain 100 persons, who in turn would be divided into groups of 50 each for each Sunday of the year, when Christian doctrine should be taught to them by a priest deputed by the Prelate, and this for the space of an hour. These residents of the parishes are to be distributed in such a way that all can attend the teaching conveniently in one of the following convents: St. Paul, St. Dominic and St. Francis, according to the declaration in the list containing the signatures of the following: the list for Bassein, Cochin, Malacca would be made and signed by their respective Prelates, while those of Goa would be signed by the Viceroy; and should anyone aware of this obligation fail to attend these classes, he should be fined one anna for the first time, two the second time, three the third time. These rolls should not include the names of shopkeepers paying rent to us nor of the physicians and on the certificate of the priest assigned to this work regarding those who failed to attend, the judges should impose penalties which will fall to the lot of the informers."

The first Constitution of the Archdiocese of Goa, written soon after in conformity with the Council in Const. VI, Tit. III contains the following: "We order that no catechumen (would-be convert) who has not been first instructed in the doctrines of our Holy Faith should be baptised. Before imparting baptism he should be taught very clearly in his own vernacular all that he has to believe viz.: the articles of the Creed and the works he has to perform, viz.: the Commandments. Without this instruction, irrespective of the time to be spent for such an instruction, no catechumen should be baptized. To receive baptism it will suffice to have knowledge of these truths even though the catechumen may not know it by heart."

Part II : AN HISTORICAL ESSAY ON THE KONKANI LANGUAGE

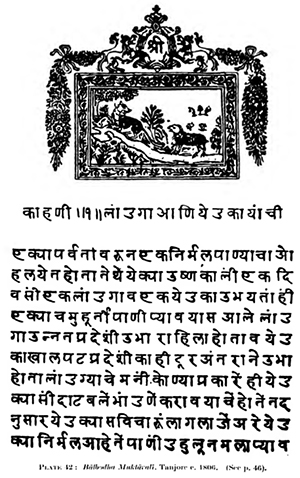

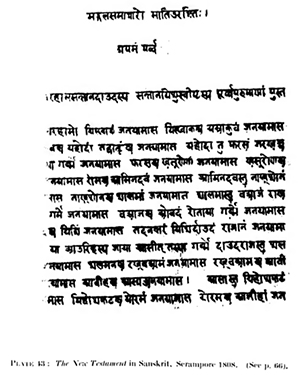

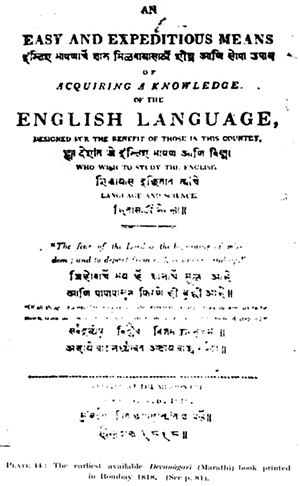

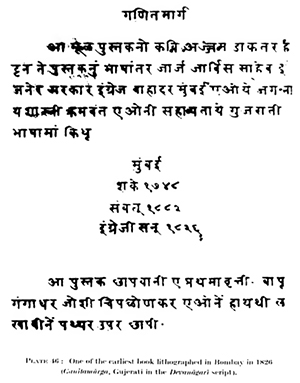

A LIFE SKETCH OF J. H. da CUNHA RIVARA* [* The author of the Historical Essay on the Konkani Language.]