Sultanu-L Mujahid Abu-L Fath Muhammad Shah Ibn Tughlik Shah

Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlik Shah, the heir apparent, succeeded his father, and ascended the throne at Tughlikabad in the year 725 H. (1325 A.D.). On the fortieth day after, he proceeded from Tughlikabad to Dehli, and there in the ancient palace took his seat upon the throne of the old Sultans. *** 2 [A long strain of eulogy follows, from which one or two passages have been selected.]

In the calligraphy of books and letters Sultan Muhammad abashed the most accomplished scribes. The excellence of his hand-writing, the ease of his composition, the sublimity of his style, and the play of his fancy, left the most accomplished teachers and professors far behind. He was an adept in the use of metaphor. If any teacher of composition had sought to rival him, he would have failed. He knew by heart a good deal of Persian poetry, and understood it well. In his epistles he showed himself skilled in metaphor, and frequently quoted Persian verse. He was well acquainted with the Sikandar nama, and also with the Bum-i salim Namah and the Tarikh-i Mahmudi. *** No learned or scientific man, or scribe, or poet, or wit, or physician, could have had the presumption to argue with him about his own special pursuit, nor would he have been able to maintain his position against the throttling arguments of the Sultan. ***

The dogmas of philosophers, which are productive of indifference and hardness of heart, had a powerful influence over him. But the declarations of the holy books, and the utterances, of the Prophets, which inculcate benevolence and humility, and hold out the prospect of future punishment, were not deemed worthy of attention. The punishment of Musulmans, and the execution of true believers, with him became a practice and a passion. Numbers of doctors, and elders, and saiyids, and sufis, and kalandars, and clerks, and soldiers, received punishment by his order. Not a day or week passed without the spilling of much Musulman blood, and the running of streams of gore before the entrance of his palace. * * *

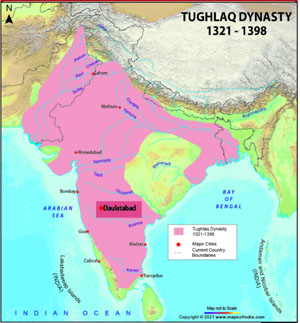

In the course of twenty-seven years, a complete karn, the King of Kings and Lord of Lords made him to prevail over the dominions of several kings, and brought the people of many countries under his rule in Hindustan, Gujarat, Malwa, the Mahratta (country), Tilang, Kampila, Dhur-samundar, Ma'bar, Lakhnauti, Sat-ganw (Chittagong), Sunar-ganw, and Tirhut. If I were to write a full account of all the affairs of his reign, and of all that passed, with his faults and shortcomings, I should fill many volumes. In this history I have recorded all the great and important matters of his reign, and the beginning and the end of every conquest; but the rise and termination of every mutiny, and of events (of minor importance), I have passed over. ***

Sultan Muhammad planned in his own breast three or four projects by which the whole of the habitable world was to be brought under the rule of his servants, but he never talked over these projects with any of his councillors and friends. Whatever he conceived he considered to be good, but in promulgating and enforcing his schemes he lost his hold upon the territories he possessed, disgusted his people, and emptied his treasury. Embarrassment followed embarrassment, and confusion became worse confounded. The ill feeling of the people gave rise to outbreaks and revolts. The rules for enforcing the royal schemes became daily more oppressive to the people. More and more the people became disaffected, more and more the mind of the king was set against them, and the numbers of those brought to punishment increased. The tribute of most of the distant countries and districts was lost, and many of the soldiers and servants were scattered and left in distant lands. Deficiencies appeared in the treasury. The mind of the Sultan lost its equilibrium. In the extreme weakness and harshness1 [[x].] of his temper he gave himself up to severity. Gujarat and Deogir were the only (distant) possessions that remained. In the old territories, dependent on Dehli, the capital, disaffection and rebellion sprung up. By the will of fate many different projects occurred to the mind of the Sultan, which appeared to him moderate and suitable, and were enforced for several years, but the people could not endure them.2 [The two MSS. differ slightly from each other, but both contain many words not in the printed text. I have taken what appears to be the general sense of what was evidently deemed an obscure and doubtful passage.] These schemes effected the ruin of the Sultan's empire, and the decay of the people. Every one of them that was enforced wrought some wrong and mischief, and the minds of all men, high and low, were disgusted with their ruler. Territories and districts which had been securely settled were lost. When the Sultan found that his orders did not work so well as he desired, he became still more embittered against his people. He cut them down like weeds and punished them. So many wretches were ready to slaughter true and orthodox Musalmans as had never before been created from the days of Adam. * * * If the twenty prophets had been given into the hands of these minions, I verily believe that they would not have allowed them to live one night. ***

The first project which the Sultan formed, and which operated to the ruin of the country and the decay of the people, was that he thought he ought to get ten or five per cent, more tribute from the lands in the Doab. To accomplish this he invented some oppressive abwabs1 [This is the first time that this word, since so well known, as come under my observation in these histories.] (cesses), and made stoppages from the land- revenues until the backs of the raiyats were broken. The cesses were collected so rigorously that the raiyats were impoverished and reduced to beggary. Those who were rich and had property became rebels; the lands were ruined, and cultivation was entirely arrested. When the raiyat in distant countries heard of the distress and ruin of the raiyats in the Doab, through fear of the same evil befalling them, they threw off their allegiance and betook themselves to the jungles. The decline of cultivation, and the distress of the raiyats in the Doab, and the failure of convoys of corn from Hindustan, produced a fatal famine in Dehli and its environs, and throughout the Doab, Grain became dear. There was a deficiency of rain, so the famine became general. It continued for some years, and thousands upon thousands of people perished of want. Communities were reduced to distress, and families were broken up. The glory of the State, and the power of the government of Sultan Muhammad, from this time withered and decayed.

The second project of Sultan Muhammad, which was ruinous to the capital of the empire, and distressing to the chief men of the country, was that of making Deogir his capital, under the title of Daulatabad. This place held a central situation: Dehli, Gujarat, Lakhnauti, Sat-ganw, Sunar-gauw, Tilang, Ma'bar, Dhur-samundar, and Kampila were about equi-distant from thence, there being but a slight difference in the distances. Without any consultation, and without carefully looking into the advantages and disadvantages on every side, he brought ruin upon Dehli, that city which, for 170 or 180 years, had grown in prosperity, and rivaled Baghdad and Cairo. The city, with its sarais and its suburbs and villages, spread over four or five kos. All was destroyed. So complete was the ruin, that not a cat or a dog was left among the buildings of the city, in its palaces or in its suburbs. Troops of the natives, with their families and dependents, wives and children, men-servants and maid-servants, were forced to remove. The people, who for many years and for generations had been natives and inhabitants of the land, were broken-hearted. Many, from the toils of the long journey, perished on the road, and those who arrived at Deogir could not endure the pain of exile. In despondency they pined to death. All around Deogir, which is an infidel land, there sprung up graveyards of Musulmans. The Sultan was bounteous in his liberality and favours to the emigrants, both on their journey and on their arrival; but they were tender, and they could not endure the exile and suffering. They laid down their heads in that heathen land, and of all the multitudes of emigrants, few only survived to return to their home. Thus this city, the envy of the cities of the inhabited world, was reduced to ruin. The Sultan brought learned men and gentlemen, tradesmen and landholders, into the city (Dehli) from certain towns in his territory, and made them reside there. But this importation of strangers did not populate the city; many of them died there, and more returned to their native homes. These changes and alterations were the cause of great injury to the country.

The third project also did great harm to the country. It increased the daring and arrogance of the disaffected in Hindustan, and augmented the pride and prosperity of all the Hindus. This was the issue of copper money.1 [The printed text adds, "his interference with buying and selling," but this is not to be found in either of my MSS., and is certainly superfluous.] The Sultan, in his lofty ambition, had conceived it to be his work to subdue the whole habitable world and bring it under his rule. To accomplish this impossible design, an army of countless numbers was necessary, and this could not be obtained without plenty of money. The Sultan's bounty and munificence had caused a great deficiency in the treasury, so he introduced his copper money, and gave orders that it should be used in buying and selling, and should pass current, just as the gold and silver coins had passed. The promulgation of this edict turned the house of every Hindu into a mint, and the Hindus of the various provinces coined krors and lacs of copper coins. With these they paid their tribute, and with these they purchased horses, arms, and fine things of all kinds. The rais, the village headmen and landowners, grew rich and strong upon these copper coins, but the State was impoverished. No long time passed before distant countries would take the copper tanka only as copper. In those places where fear of the Sultan's edict prevailed, the gold tanka rose to be worth a hundred of (the copper) tankas. Every goldsmith struck copper coins in his workshop, and the treasury was filled with these copper coins. So low did they fall that they were not valued more than pebbles or potsherds. The old coin, from its great scarcity, rose four-fold and five-fold in value. When trade was interrupted on every side, and when the copper tankas had become more worthless than clods, and of no use, the Sultan repealed his edict, and in great wrath he proclaimed that whoever possessed copper coins should bring them to the treasury, and receive the old gold coins in exchange. Thousands of men from various quarters, who possessed thousands of these copper coins, and caring nothing for them, had flung them into corners along with their copper pots, now brought them to the treasury, and received in exchange gold tankas and silver tankas, shash-ganis and du-ganis, which they carried to their homes. So many of these copper tankas were brought to the treasury, that heaps of them rose up in Tughlikabad like mountains. Great sums went out of the treasury in exchange for the copper, and a great deficiency was caused. When the Sultan found that his project had failed, and that great loss had been entailed upon the treasury through his copper coins, he more than ever turned against his subjects.

The fourth project which diminished his treasury, and so brought distress upon the country, was his design of conquering Khurasan and 'Irak. In pursuance of this object, vast sums were lavished upon the officials and leading men of those countries. These great men came to him with insinuating proposals and deceitful representations, and as far as they knew how, or were able, they robbed the throne of its wealth. The coveted countries were not acquired, but those which he possessed were lost; and his treasure, which is the true source of political power, was expended.

The fifth project * * * was the rising of an immense army for the campaign against Khurasan. * * * In that year three hundred and seventy thousand horse were enrolled in the muster- master's office. For a whole year these were supported and paid; but as they were not employed in war and conquest and enabled to maintain themselves on plunder, when the next year came round, there was not sufficient in the treasury or in the feudal estates (ikta) to support them. The army broke up; each man took his own course and engaged in his own occupations. But lacs and krors had been expended by the treasury.

The sixth project, which inflicted a heavy loss upon the army, was the design which he formed of capturing the mountain of Kara-jal.1 [The printed text as "Farajal," and this is favoured to some extent by one MS., but the other is consistent in reading Kara-jal. See supra, Vol. I., p. 46, note 2.] His conception was that, as he had undertaken the conquest of Khurasan, he would (first) bring under the dominion of Islam this mountain, which lies between the territories of Hind and those of China, so that the passage for horses and soldiers and the march of the army might be rendered easy. To effect this object a large force, under distinguished amirs and generals, was sent to the mountain of Kara-jal, with orders to subdue the whole mountain. In obedience to orders, it marched into the mountains and encamped in various places, but the Hindus closed the passes and cut off its retreat. The whole force was thus destroyed at one stroke, and out of all this chosen body of men only ten horsemen returned to Delhi to spread the news of its discomfiture. * * *

Revolts. —

* * The first revolt was that of Bahram Abiya at Multan. This broke out while the Sultan was at Deogir. As soon as he heard of it he hastened back to his capital, and collecting an army he marched against Multan. When the opposing forces met, Bahram Abiya was defeated. His head was cut off and was brought to the Sultan, and his army was cut to pieces and dispersed. * * * The Sultan returned victorious to Dehli, where he stayed for two years. He did not proceed to Deogir, whither the citizens and their families had removed. Whilst he remained at Dehli the nobles and soldiers continued with him, but their wives and children were at Deogir. At this time the country of the Doab was brought to ruin by the heavy taxation and the numerous cesses. The Hindus burnt their corn stacks and turned their cattle out to roam at large. Under the orders of the Sultan, the collectors and magistrates laid waste the country, and they killed some landholders and village chiefs and blinded others. Such of these unhappy inhabitants as escaped formed themselves into bands and took refuge in the jungles. So the country was ruined. The Sultan then proceeded on a hunting excursion to Baran, where, under his directions, the whole of that country was plundered and laid waste, and the heads of the Hindus were brought in and hung upon the ramparts of the fort of Baran.

About this time the rebellion of Fakhra broke out in Bengal, after the death of Bahram Khan (Governor of Sunar-ganw). Fakhra and his Bengali forces killed Kadar Khan (Governor of Lakhnauti), and cut his wives and family and dependents to pieces. He then plundered the treasures of Lakhnauti, and secured possession of that place, and of Sat-ganw and Sunar- ganw. These places were thus lost to the imperial throne, and, falling into the hands of Fakhra and other rebels, were not recovered. At the same period the Sultan led forth his army to ravage Hindustan. He laid the country waste from Kanauj to Dalamu, and every person that fell into his hands he slew. Many of the inhabitants fled and took refuge in the jungles, but the Sultan had the jungles surrounded, and every individual that was captured was killed.

While he was engaged in the neighbourhood of Kanauj a third revolt broke out. Saiyid Hasan, father of Ibrahim, the pursebearer, broke out into rebellion in Ma'bar, killed the nobles, and seized upon the government. The army sent from Dehli to recover Ma'bar, remained there. When the Sultan heard of the revolt he seized Ibrahim and all his relations. He then returned to Dehli for reinforcements, and started from thence to Deogir, in order to prepare for a campaign against Ma'bar. He had only marched three or four stages from Dehli when the price of grain rose, and famine began to be felt. Highway robberies also became frequent in the neighbourhood. When the Sultan arrived at Deogir he made heavy demands upon the Musulman chiefs and collectors of the Mahratta country, and his oppressive exactions drove many persons to kill themselves. Heavy abwabs also were imposed on the country, and persons were specially appointed to levy them. After a short time he sent Ahmad Ayyaz (as lieutenant) to Dehli, and he marched to Tilang. When Ayyaz arrived in Dehli he found that a disturbance had broken out in Lahor, but he suppressed it. The Sultan arrived at Arangal, where cholera (waba) was prevalent. Several nobles and many other persons died of it. The Sultan also was attacked. He then appointed Malik Kabul, the naib-wazir, to be ruler over Tilang, and himself returned homewards with all speed. He was ill when he reached Deogir, and remained there some days under treatment. He there gave Shahab Sultani the title of Nusrat Khan, and made him governor of Bidar and the neighbourhood, with a fief of a lac of tankas. The Mahratta country was entrusted to Katlagh Khan, The Sultan, still ill, then set off for Dehli, and on his way he gave general permission for the return home of those people whom he had removed from Dehli to Deogir, Two or three caravans were formed which returned to Dehli, but those with whom the Mahratta country agreed remained at Deogir with their wives and children.

The Sultan proceeded to Dhar, and being still indisposed, he rested a few days, and then pursued his journey through Malwa. Famine prevailed there, the posts were all gone off the road, and distress and anarchy reigned in all the country and towns along the route. When the Sultan reached Dehli, not a thousandth part of the population remained. He found the country desolate, a deadly famine raging, and all cultivation abandoned. He employed himself some time in restoring cultivation and agriculture, but the rains fell short that year, and no success followed. At length no horses or cattle were left; grain rose to 16 or 17 jitals a sir, and the people starved. The Sultan advanced loans from the treasury to promote cultivation, but men had been brought to a state of helplessness and weakness. Want of rain prevented cultivation, and the people perished. The Sultan soon recovered his health at Dehli.

Whilst the Sultan was thus engaged in endeavouring to restore cultivation, the news was brought that Shahu Afghan had rebelled in Multan, and had killed Bihzad, the naib. Malik Nawa fled from Multan to Dehli. Shahu had collected a party of Afghans, and had taken possession of the city. The Sultan prepared his forces and marched towards Multan, but he had made only a few marches when Makhduma-i Jahan, his mother, died in Dehli. ** The Sultan was much grieved. ** He pursued his march, and when he was only a few marches from Multan, Shahu submitted, and sent to say that he repented of what he had done. He fled with his Afghans to Afghanistan, and the Sultan proceeded to Sannam. From thence he went to Agroha, where he rested awhile, and afterwards to Dehli, where the famine was very severe, and man was devouring man. The Sultan strove to restore cultivation, and had wells dug, but the people could do nothing. No word issued from their mouths, and they continued inactive and negligent. This brought many of them to punishment.

The Sultan again marched to Sannam and Samana, to put down the rebels, who had formed mandals (strongholds?), withheld the tribute, created disturbances, and plundered on the roads. The Sultan destroyed their mandals, dispersed their followers, and carried their chiefs prisoners to Dehli. Many of them became Musulmans, and some of them were placed in the service of noblemen, and, with their wives and children, became residents of the city.1 [The work is not divided into chapters, or other divisions, systematically, in a way useful for reference, so the occasional headings have not been given in the translation. But the heading of the section in which this passage occurs is more explicit than the narrative; it says — "Campaign of Sultan Muhammad in Sannam, Samana, Kaithal and Kuhram, and devastation of those countries which had all become rebellious. Departure of the Sultan to the hills; subjugation of the ranas of the hills; the carrying away of the village chiefs and head men, Birahas, Mandahars, Jats, Bhats, and Manhis to Dehli. Their conversion to Islam, and their being placed in the charge of the nobles in the capital."] They were torn from their old lands, the troubles they had caused were stopped, and travellers could proceed without fear of robbery.

While this was going on a revolt broke out among the Hindus at Arangal. Kanya Naik had gathered strength in the country. Malik Makbul, the naib-wazir, fled to Dehli, and the Hindus took possession of Arangal, which was thus entirely lost. About the same time one of the relations of Kanya Naik, whom the Sultan had sent to Kambala,2 [Kampala is the name given in the print, but both MSS. read ''Kambala," making it identical with the place mentioned directly afterwards. I have not been able to discover the place. The author probably took the name to be identical with that of Kampila in the Doab.] apostatized from Islam and stirred up a revolt. The land of Kambala also was thus lost, and fell into the hands of the Hindus. Deogir and Gujarat alone remained secure. Disaffection and disturbances arose on every side, and as they gathered strength the Sultan became more exasperated and more severe with his subjects. But his severities only increased the disgust and distress of the people. He stayed for some time in Dehli, making loans and encouraging cultivation; but the rain did not fall, and the raiyats did not apply themselves to work, so prices rose yet higher, and men and beasts died of starvation. *** Through the famine no business of the State could go on to the Sultan's satisfaction.

The Sultan perceived that there was no means of providing against the scarcity of grain and fodder in the capital, and no possibility of restoring cultivation without the fall of rain. He saw also that the inhabitants were daily becoming more wretched; so he allowed the people to pass the gates of the city and to remove with their families towards Hindustan, * * * so many proceeded thither. The Sultan also left the city, and, passing by Pattiali and Kampila,1 [Towns in Farrukhabad.] he halted a little beyond the town of Khor, on the banks of the Ganges, where he remained for a while with his army. The men built thatched huts, and took up their abode near the cultivated land. The place was called Sargdwari [Heaven's gate). Grain was brought thither from Karra and Oudh, and, compared with the price at Dehli, it was cheap. While the Sultan was staying at this place 'Ainu-l Mulk held the territory of Oudh and Zafarabad. His brothers had fought against and put down the rebels, thus securing these territories, * * and the Malik and his brothers sent to Sargdwari and to Dehli money, grain and goods, to the value of from seventy to eighty lacs of tankas. This greatly increased the Sultan's confidence in 'Ainu-l Mulk, and confirmed his opinion of his ability. The Sultan had just before been apprized that the officials of Katlagh Khan at Deogir had, by their rapacity, reduced the revenues; he therefore proposed to make 'Ainu-l Mulk governor of Deogir, and to send him there with his brothers and all their wives and families, and to recall Katlagh Khan with his adherents. When 'Ainu-l Mulk and his brothers heard of this design, they were filled with apprehension, and attributed it to the treachery of the Sultan. They had held their present territories for many years, and many nobles and officials of Dehli, through fear of the Sultan's severity, had left the city, alleging the dearness of grain as the reason, and had come to Oudh and Zafarabad, with their wives and families. Some of them became connected with the Malik and his brothers, and some of them received villages. * * The Sultan was repeatedly informed of this, and it made him very angry, but he kept this feeling to himself, until one day, while at Sarg-dwari, he sent a message to 'Ainu-l Mulk, ordering that all the people of note and ability, and all those who had fled from Dehli to escape punishment, should be arrested and sent bound to Dehli. *** This message, so characteristic of the Sultan's cruelty, enhanced the fears of the Malik and his brothers, and they felt assured that the Sultan's intention was to send them to Deogir and there perfidiously destroy them. They were filled with abhorrence, and began to organize a revolt.

About this time, during the Sultan's stay at Dehli and his temporary residence at Sarg-dwari, four revolts were quickly repressed. First. That of Nizam Ma-in at Karra. *** 'Ainu-l Mulk and his brothers marched against this rebel, and having put down the revolt and made him prisoner, they flayed him and sent his skin to Dehli. Second, That of Shahab Sultani, or Nusrat Khan, at Bidar. * * * In the course of three years he had misappropriated about a kror of tankas from the revenue. * * The news of the Sultan's vengeance reached him and he rebelled, but he was besieged in the fort of Bidar, *** which was captured, and he was sent prisoner to Dehli. Third, That of 'Alisha, nephew of Zafar Khan, which broke out a few months afterwards in the same district. *** He had been sent from Deogir to Kulbarga to collect the revenues, but finding the country without soldiers and without any great men, he and his brothers rebelled, treacherously killed Bhairan, chief of Kulbarga, and plundered his treasures. He then proceeded to Bidar and killed the naib, after which he held both Bidar and Kulbarga, and pushed his revolt. The Sultan sent Katlagh Khan against him *** from Deogir, and the rebel met him and was defeated. * * * He then fled to Bidar, where he was besieged and captured. He and his brothers were sent to the Sultan, *** who ordered them to Ghazni. They returned from thence, and the two brothers received punishment. Fourth. The revolt of 'Ainu-l Mulk and his brothers at Sarg-dwari. The Malik was an old courtier and associate of the Sultan, so he feared the weakness of his character and the ferocity of his temper. Considering himself on the verge of destruction, he, by permission of the Sultan, brought his brothers and the armies of Oudh and Zafarabad with him when he went to Sargdwari, and they remained a few kos distant. One night be suddenly left Sarg-dwari and joined them. His brothers then passed over the river with three or four hundred horse, and, proceeding towards Sarg-dwari, they seized the elephants and horses which were grazing there, and carried them off. A serious revolt thus arose at Sarg-dwari. The Sultan summoned forces from Samana, Amroha, Baran, and Kol, and a force came in from Ahmadabad. He remained a while at Sarg-dwari to arrange his forces, and then marched to Kanauj and encamped in its suburbs. 'Ainu-l Mulk and his brothers knew nothing of war and fighting, and had no courage and experience. They were opposed by Sultan Muhammad, *** who had been victorious in twenty battles with the Mughals. In their extreme ignorance and folly they crossed the Ganges below Bangarmu, *** and thinking that the Sultan's severity would cause many to desert him, they drew near to offer battle. *** In the rooming one division of the Sultan's forces charged and defeated them at the first attack. 'Ainu-l Mulk was taken prisoner, and the routed forces were pursued for twelve or thirteen kos with great loss. The Malik's two brothers, who were the commanders, were killed in the fight. Many of the fugitives, in their panic, cast themselves into the river and were drowned. The pursuers obtained great booty. Those who escaped from the river fell into the hands of the Hindus in the Mawas and lost their horses and arms. The Sultan did not punish 'Ainu-l Mulk, for he thought that he was not wilfully rebellious, but had acted through mistake. *** After a while he sent for him, treated him kindly, gave him a robe, promoted him to high employment, and showed him great indulgence. His children and all his family were restored to him.

After the suppression of this revolt, the Sultan resolved on going to Hindustan, and proceeded to Bahraich, where he paid a visit, and devoutly made offerings to the shrine of the martyr Sipah-salar Mas'ud,1 [The tomb of Mas'ud had thus become a place of sanctity at this time. See Vol. II. App., pp. 513, 549.] one of the heroes of Sultan Mahmud Subuktigin. ***