Chapter 3: Diderot's Buddhist Brahmins

In the first volumes of the central monument of the French Enlightenment, the Encyclopedie, there are several articles about Asian religions that are either signed by or attributed to Denis DIDEROT (1713-84). The most important ones in the first volumes are entitled "ASIATIQUES. Philosophie des Asiatiques en general" (1751:1.752-55), "BRACHMANES" (1752:2.391), and "BRAMINES" (1752:2.393-94). Today, these articles have such a bad reputation that they are often criticized and held up for ridicule. For example, Wilhelm Halbfass wrote,

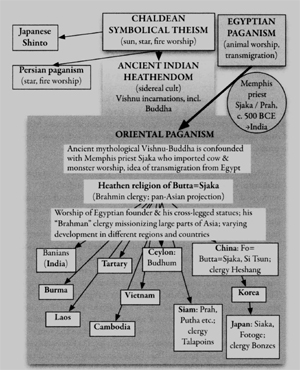

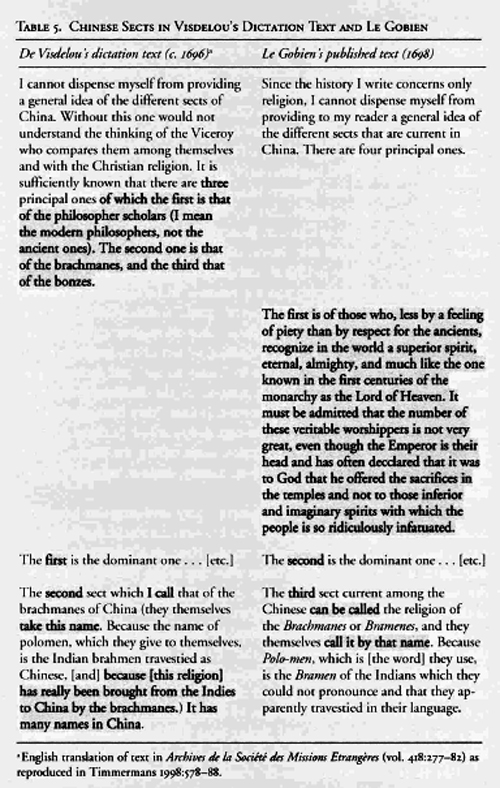

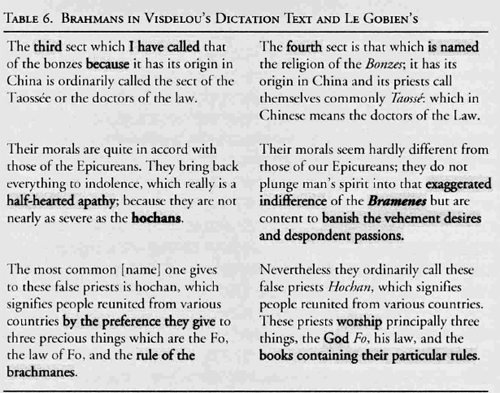

In the article "Brachmanes," Diderot discusses what he calls "extravagances tout-a-fait incroyables," stating that the persons who had referred to the Brahmins as "sages" must have been even crazier than the Brahmins themselves. The article entitled "Bramines" is essentially a summary and in part literal paraphrase of the article "Brachmanes" contained in Bayle's Dictionnaire historique et critique; it also reproduces a mixup of Buddhism and Brahminism occurring in the original: citing the Jesuit Ch. LeGobien, Bayle described a Brahminic sect thought to be living in China as worshippers of the "God Fo." (Halbfass 1990:59)

Diderot's "inaccuracy and lack of originality" (p. 60), Halbfass argues, is evident in his use of "Bayle's and Le Gobien's portrayal of the Chinese 'Brahmins' and Buddhists" to conjure up a vision of "quietism" and love of "nothingness" among the Indians and thus to highlight "their desire to stupefy and mortify themselves" (p. 59). Halbfass cites the following passage from Diderot's article on the "Bramines" as an illustration:

They assert that the world is nothing but an illusion, a dream, a magic spell, and that the bodies, in order to be truly existent, have to cease existing in themselves, and to merge into nothingness, which due to its simplicity amounts to the perfection of all beings. They claim that saintliness consists in willing nothing, thinking nothing, feeling nothing .... This state is so much like a dream that it seems that a few grains of opium would sanctify a brahmin more surely than all his efforts. (pp. 59-60)

Diderot's only contribution in this passage, Halbfass contends, was to add to his paraphrase of Bayle the reference to opium; but even this was not original since this is "a motif which we find also in the Essais de theodicee, which Leibniz published in 1710" (p. 60). As is well known, this "opium" motif reappeared in the nineteenth century "among Hegel and other critics of Indian thought" (p. 60) and, broadened by Marx to apply to religion in general, found its way into the minds of hundreds of millions of twentieth-century communists: religion as opiate for the people. Halbfass could also have cited the very first sentence of Diderot's article, which precedes the given quotation and presents his "mixup of Buddhism and Brahminism" in a nutshell:

BRAMINES, or BRAMENES, or BRAMINS, or BRAMENS, ... Sect of Indian philosophers anciently called Brachmanes. See BRACHMANES. These are priests who principally revere three things: the god Fo, his law, and the books that contain their constitutions. (Diderot 1752:2.393)

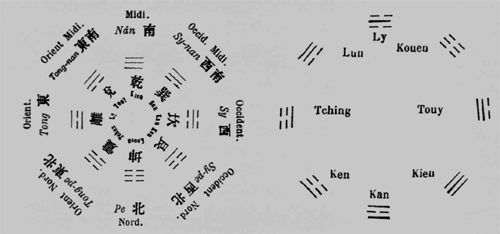

Diderot here clearly defines the subjects of his article, the Brahmins, as priests of the "god Fo" who, as we have seen, was already in the seventeenth century often identified as Buddha. Diderot's Brahmins believe in this Fo, preach his doctrine (the dharma or law), and value the books that contain his teachings. Today we are able to identify these three items as the "three jewels" or "three treasures" that are ceaselessly evoked and pledged allegiance to by Buddhists of all nations. While the first two (Fo = Buddha and law = dharma) clearly evoke the first two treasures, the third treasure is now known to be the sangha, that is, the Buddhist community, rather than its sacred scriptures. Historians of the European discovery of Buddhism, who tend to be rather unforgiving schoolmasters, of course also denounce Diderot's terrible "mixup." In 1952, Cardinal de Lubac used even stronger terms than Halbfass:

Diderot makes himself the echo of such phantasmagoric science. The diverse articles of the Encyclopedie that touch on Buddhism (several of which are by Diderot himself) rest on some superficial readings without the slightest attempt at critique.1 They range from 1751 to 1765 and are a bunch of hypotheses, gossip, and errors that are mutually contradictory. The Buddha, who is habitually named Xekia, or Xaca, or Siaka, supposedly is an African from Ethiopia (Diderot read the critical note of Abbe Banier about the text by Kaempfer and attempts to harmonize the two authors); or maybe he was a Jew -- at any rate, he had knowledge of the books of Israel. ... He supposedly founded, in Southern India, "the sect of Hylobians, the most savage of the gymnosophists" and is said to have written all of his exoteric doctrine on tree leaves. (de Lubac 2000:121-22)

Citing the beginning of Diderot's "Brahmin" article, de Lubac makes fun of Diderot's "sketchy comparatism" and of his claim that the Jewish kabbalists modeled their ensoph doctrine on the "emanatism of Xekia" (p. 122).

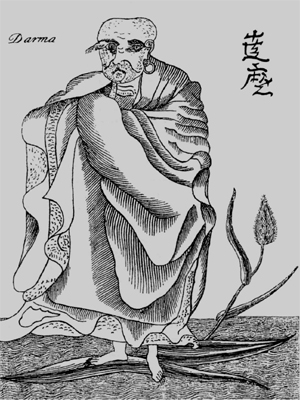

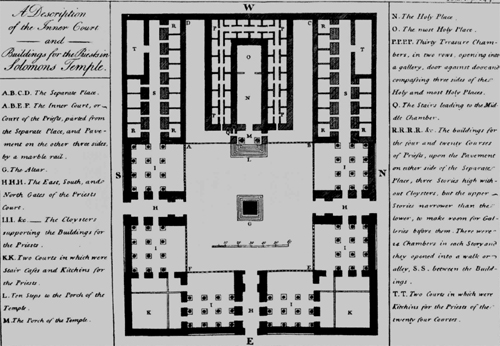

Here, instead of comparing and ridiculing information about Asian religions from many different Encyclopedie articles by Diderot and other authors, just three entries from the first two volumes will be analyzed: "ASIATIQUES. Philosophie des Asiatiques en general" (1751:1.752-55), "BRACHMANES" (1752:2.391), and "BRAMINES" (1752:2.393-94). They are likely to be from the pen of Diderot. At any rate, they present a mid-eighteenth-century view of Asian religions by an intelligent Frenchman who, while primarily relying on the work of Pierre Bayle (1702) and Johann Jacob Brucker (1742-44), made direct and indirect use of much of the information available in Europe at that time. Instead of the "monkey show" approach where historical views are held up for ridicule like chimpanzees dressed in human clothes who must show to the laughing public how far we have come along, this chapter will present the main points of Diderot's view of Asian religions in historical context. His "lack of originality," "sketchy comparatism," and especially his "mixup" of different religions are thus seen as worthy objects of study rather than ridiculous defects. Just as the island of Hokkaido ("Yeso") at the northern end of Japan was for a long time thought to be so gigantic as to stretch all the way to North America, the dimensions and confines of Asian religions were in Diderot's time still rather hazy. In this respect discoveries and explorations of religions are not so different from those of barely known lands. Even a century after Diderot's articles, the historical and doctrinal dimensions of Asian religions were still far from clear, and many boundaries that have since been drawn (for example, those dividing "shamanism" from "Buddhism" in Tibet or "folk religion" from "Daoism" in China) are so problematic that some professors of religious studies would love to wipe them off the map. With regard to the discovery of Asian religions, parading "false" ideas (for example, about the founder of Buddhism) is far easier than understanding why those ideas arose and realizing the fragility of present-day certitudes. As a matter of fact, two centuries of "scientific" study have utterly failed to produce a consensus even about the centuries in which Buddhism's founder lived, and skeptics who argue that he is just one more legend that took on flesh and bones are not easily refuted. Was not the life story of a popular Christian saint of the Middle Ages, St. Josaphat, derived from legends about the Buddha and unmasked as a pious fiction, even though some of "his" bones are to this day revered in Antwerp's St. Andries Church? In 1997 the church's friendly sacristan got me a ladder so I could see how the Buddha legend calcified (see Figure 4).

As we will see in the present and subsequent chapters, variants of Diderot's idea of a pan-Asian religion or philosophy were very popular in his time and should hardly be fodder for reproaches and "monkey show" treatment. Indeed, anybody who believed in the Old Testament account of the deluge and the dispersion of peoples after Babel was bound to favor monogenetic hypotheses and to presuppose common roots of possibly unrelated phenomena. The idea of a pan-Asian religion or doctrine -- conceived either positively as an ancient theology or negatively as an ancient idolatry -- was not only common throughout Diderot's century but dominant. It is a subject well worth exploring; after all, almost every chapter of this book shows that this was a far more influential factor in the birth of Orientalism than the much-evoked and blamed colonialism. This chapter will describe key features of Diderot's "philosophie asiatique" and dig into the past to expose some of its main roots. If the previous chapter showed how deeply intertwined the European discoveries of "Brahmanism" and Buddhism in the first quarter of the eighteenth century were, the present chapter will expand the field of view both backward toward the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and forward to the mid-eighteenth century when Diderot compiled his first articles on Asian religions.

Figure 4. The bones of a legend: relics of Saint Josaphat (St. Andrieskerk, Antwerp; photo by Urs App).

Exoterica and Esoterica

We have seen in the previous chapters that the Jesuits of the Japan mission already began studying the Japanese varieties of Buddhism in the 1550s. This was not exactly a nineteenth-century philological workshop. In his letters from Yamaguchi of 1551, Cosme de TORRES (1510-70) distinguished several groups of Japanese heathens including worshipers of Shaka, Amida, and a sect called "Jenxus" (Jap. Zen-ska, Zen sect). According to Frater Cosme, who was the first European to mention this sect by name, Zen adepts teach in two ways [dos maneras]. The first is described as follows:

One way says that there is no soul, and that when a man dies, everything dies, since they say that what has been created out of nothing [crio de nada] returns to nothing [se convierte en nada]. These are men of great meditation [grandes meditaciones], and it is difficult to make them understand the law of God. It is quite a job [mucho trabajo] to refute them. (Schurhammer 1929:95)

According to Fr. Cosme's subsequent letter of October 20, 1551, these men held that "hell and punishment for the evil ones are not in another life but in this one" and "denied that there is a hell after a man dies" (p. 101). Numerous adepts of the Zen sect, both priests and laymen, informed the Jesuit missionaries that "there are no saints and that it is not necessary to search for a way [buscar su caminho] since what had come into existence from nothing could not but return to nothing [que de nada foi echo, nao puede deixar de se comvertir em nadie]" (p. 99). When the missionaries tried to convince these representatives of Zen that "there is a principle that constitutes the origin of all other things," the Japanese are said to have replied:

This [nothing] is a principle from which all things arise: men, animals, plants: every created thing has in itself this principle, and when men or animals die they return to the four elements, into that which they had been, and this principle returns to that which it is. This principle, they say, is neither good nor bad, knows neither glory nor punishment, neither dies nor lives, in a manner that it is a "no" [de manera que es hum no]. (p. 99)

Such views uncannily resemble the "internal teaching" described in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and they confirm that its principal features emerged in Japan when the first missionaries engaged in conversations with representatives of the Zen denomination who might have told told them about Bodhidharma's legendary responses to Emperor Wu ("Empty, nothing holy"; "no merit") and kept uttering the word "mu" (nothingness). In contrast to the inner teaching, the second manner of teaching described by Frater Cosme seems to accept an eternal soul and transmigration:

There are others who say that souls [las animas] have existed and will exist forever and that with the death of the body each of the four elements returns to its own place, as does the soul that returns into what it was before it animated that body. Others say that, after the death of the body, the souls return to enter different bodies and thus ceaselessly are born and die again. (p. 95)

This teaching encapsulates essential elements of what later came to be known as the "exterior" teaching of Buddhism: an eternal soul and transmigration. Tutored by former Buddhist monks and knowledgeable laymen, the missionaries in the following decades gradually became more familiar with the sects, clergies, rituals, and doctrines of Japan's rich Buddhist tradition and learned of the distinction between an "outer" or provisional teaching for the common people (Jap. gonkyo) and an "inner" or true teaching (Jap. jikkyo). In the catechism of 1586, Alessandro VALIGNANO's entire presentation of doctrines and sects is based on the distinction between provisional (gon) and real (jitsu) teachings (Valignano 1586:4v).

Today we know that various forms of this "gon-jitsu" distinction played a major role in the history of Buddhism. During the first centuries of the common era, when the Indian religion took root in China, various classification schemes (Ch. panjiao) were created by the Chinese to bring order into a bewildering array of Buddhist doctrines and texts. Some made use of the Indian Buddhist "two-truths" scheme, which asserts that, apart from the absolute truth of the awakened, there is also a provisional truth designed to accommodate deluded beings and help them reach enlightenment. Others came to attach particular doctrines and texts to phases of the Buddha's life, and naturally those of one's preferred sect tended to be associated with particularly poignant events of the founder's life, such as the first sermon after his enlightenment or the ultimate teachings before passing away. Such schemes often employed, in one form or another, the distinction between a "provisional" (Jap. gonkyo) and "genuine" or "real" teaching (Jap. jikkyo), which is exactly what the Buddhist informers must have explained to Valignano and his fellow Jesuits. A related distinction is that between exoteric and esoteric teachings (Jap. kengyo and mikkyo) that was promoted, among others, by the famous founder of Japanese esoteric Buddhism, Kakai (734-835; Abe 1999:9). But in the sixteenth century most of this was unknown. However, through the inclusion of Valignano's catechism in Antonio Possevino's Bibliotheca selecta of 1593, the distinction between provisional and real (or exoteric and esoteric) teachings and sects in Japan gained a foothold in Europe among Jesuits, their students, and some sections of Europe's educated class.

As early as the mid-sixteenth century, Jesuit missionaries also linked this distinction between exoteric and esoteric doctrines with phases of the Buddha's life. In 1551 Japanese Buddhists informed the Jesuit brother Juan Fernandez, who spoke some Japanese, that the founder of their religion, Shaka, "also wrote books so that they would pray to him and be saved." But at the age of 49 years, so Fernandez reported,2 Shaka had suddenly changed his approach and confessed that "in the past he had been ignorant, which is why he wrote so much." Based on his own experience Shaka thereafter discouraged people from reading his old writings and advocated "meditation in order to learn about oneself and of one's end" (Schurhammer 1929:82). In the first comprehensive report about Buddhist sects and doctrines that reached the West (the Sumario de los errores of 1556), certain Buddhist texts were thus associated with specific sects, and Shaka was said to have dismissed his earlier writings: "They said that many people followed him and that he had 80,000 disciples. And ultimately, after having spent 44 years writing these scriptures, he said that nothing of that was true and that all was fombem (Jap. hoben, expedient means]" (Ruiz-de-Medina 1990:664).

Translation of the Inscription on the Eastern compartment.

Thus spake king Devanampiya Piyadasi: — In the twelfth year of my anointment, a religious edict (was) published for the pleasure and profit of the world; having destroyed that (document) and regarding my former religion as sin, I now for the benefit of the world proclaim the fact. And this, (among my nobles, among my near relations, and among my dependents, whatsoever pleasures I may thus abandon,) I therefore cause to be destroyed; and I proclaim the same in all the congregations; while I pray with every variety of prayer for those who differ from me in creed, that they following after my proper example may with me attain unto eternal salvation: wherefore the present edict of religion is promulgated in this twenty-seventh year of my anointment.

Thus spake king Devanampiya Piyadasi:— Kings of the olden time have gone to heaven under these very desires. How then among mankind may religion (or growth in grace) be increased? yea through the conversion of the humbly-born shall religion increase.

Thus spake king Devanampiya Piyadasi: — The present moment and the past have departed under the same ardent hopes. How by the conversion of the royal-born may religion be increased? Through the conversion of the lowly-born if religion thus increaseth, by how much (more) through the conviction of the high-born, and their conversion, shall religion increase? Among whomsover the name of God resteth (?) verily this is religion, (or verily virtue shall there increase.)

Thus spake king Devanampiya Piyadasi: — Wherefore from this very hour I have caused religious discourses to be preached; I have appointed religious observances — that mankind having listened thereto shall be brought to follow in the right path and give glory unto god, (Agni.?)

***

1 / Devanampiya piyadasi Laja hevam aha. Duwadasa

2 / vasa abhisitename, dhammalipi likhapita 1 [The omission of the demonstrative pronoun iyam, this, which in the other tablets is united to dhammalipi, requires a different turn to the sentence, such as I have ventured to adopt in the translation: In the 12th year of his reign the raja had published an edict, which he now in the 27th considered in the light of a sin. His conversion to Buddhism then must have been effected in the interval, and we may thus venture a correction of 20 years in the date assigned to Piatissa's succession in Mr. Turnour's table, where he is made to come to the throne on the very year set down for the deputation of Mahinda and the priests from Asoka's court to convert the Ceylon court.] lokasa

3 / hitasukhaye 2: [I have placed the stop here because the following word, setam seemed to divide the sentence 'an edict was promulgated in the 12th year for the good of my subjects, so this having destroyed, or cancelled, I — ' setam seems compounded of sa employed conjunctively as in modern Hindi, and etam this.] setam apahaita 3, [Apahata [x] (is) abandoned: viz. the former dhammalipi setam (neuter) is perhaps used for [x] sa-iyam (feminine) so, that; or supplying the word [x] it may run in the neuter [x] and continuing [x] (Pali tam-tam) [x] this (being) as it were a sin according to dharma vardhi (my new religion, so), the expression being connected by tatpurusha samasa.] tamtam dhammavadhi papova

4 / hevam lokasa hetavakhati pativekhami 4. [The text has petavakhati, which may be either read hitavakhati (S. [x]) a description for the benefit; or hetu vakhati (S. [x]) 'description for the sake,' to wit [x] of mankind. 4. Pati vekhami (vakhami) S. [x] I now formally renounce, — the affix prati gives the sense of recantation from a former opinion.] Atha iyam 5:— [Lipi or katha understood to agree with iyam; atha iyam, may be rendered "furthermore."]

5 / natisu, 6 [Sanskrit, [x], among lords, companions, and lieges. The last word may also be read [x], among the sincere or faithful (adherents).] hevam patiyasannesu, hevam apakathesu

6 / kimankani sukham avahamiti 7; [Sanskrit, [x], 'how many pleasures I forego;' [x], 'and I altogether burn and destroy.'] tathacha vidahami; hemeva....

21 / anusasami 16. [[x] (sub. [x]) [x], 'at this time I have ordered sermons to be preached (or [x] to my sons? or [x] virtuous sermons) and I have established religious ordinances.'] Etam jane suta anupatipajisati 17 [[x] 'so that among men there shall be conformity and obedience.' It may be read [x], 'which the people having heard (shall obey), and I have preferred this latter reading because it gives a nominative to the verb.] agnim namisati 18. [The anomalous letter of the penultimate word seems to be a compound of gni and anuswara, [x] which would make the reading agnim namisati 'and shall give praise unto, Agni,' but no reason can be assigned for employing such a Mithraic name for the deity in a Buddhist document. A facsimile alone from the pillar can solve this difficulty, for we have here no other text to collate with the Feroz lat inscription. It is probably the same word which is illegible in the 19th line. The only other name beginning with [x] a, which can well be substituted, is [x] Aja, a name of Brahma, Vishnu or Siva, or in general terms, 'God.' Perhaps [x] Aja, 'illusion personified as Sakti—(Maya) may have more of a Buddhistic acceptation.]

-- Interpretation of the most ancient of the inscriptions on the pillar called the lat of Feroz Shah, near Delhi, and of the Allahabad, Radhia [Lauriya-Araraj (Radiah)] and Mattiah [Lauriya-Nandangarh (Mathia)] pillar, or lat, inscriptions which agree therewith, by James Prinsep, Sec. As. Soc. &c., 1837

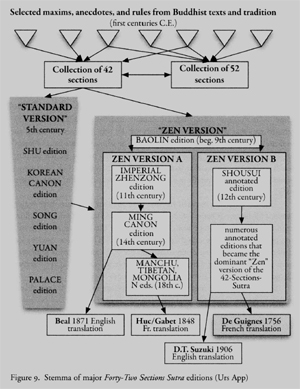

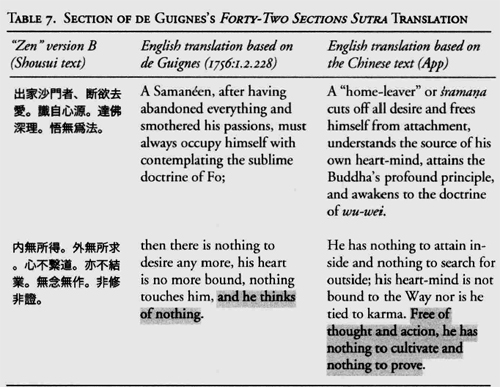

However, Matteo Ricci's 1615 description of the sect of "sciequia or omitofo" (Shakya/Amitabha) and the corresponding Japanese teaching of "sotoqui" (Jap. hotoke, that is, buddhas) shows no trace of such a fundamental distinction between expedient and true teaching and exhibits little familiarity with Buddhism's "multitude of books" that, according to Ricci, "were either brought from the West or (which is more likely) composed in the Kingdom of China itself" (Ricci 1615:122). But the date of 65 C.E. from the preface of the Forty-Two Sections Sutra, along with its tale of the transfer of this religion from India to China and of the translation of its texts, became fixtures in virtually all subsequent Western accounts. This sutra was thus, long before de Guignes's 1756 translation (see Chapter 4), instrumental in attaching a founder's name (Fo/Buddha), a place of origin (India), a date of the first transmission to China (65 CE.), a body of sacred scriptures including the sutra itself, and an eastward trajectory (from India to Siam, China, and Japan) for a large religion dominant in major parts of Asia. Ricci's account, as edited by Nicolas Trigault, was read all over Europe in schools and refectories and published in several languages. It was a work that opened up a whole new world for a surprisingly large public.

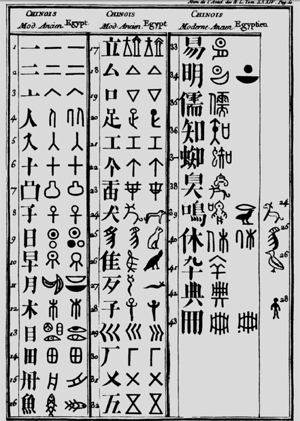

But after Ricci's death in 1610 and the publication of his view of Chinese religions by Trigault (1615), Ricci's critic Joao RODRIGUES (1561-1633) applied the distinction between exoteric and esoteric teachings more broadly to all three major religions of China and linked it to the ancient use of symbols in the Middle East and Egypt (see also Chapter I). Rodrigues's view of a common root of Asia's major religions and his conviction that all of them used symbols to hide the real content of their teaching from the general public were influential in several respects. Chinese "idolatry" was not an amorphous mass but consisted of several well-defined creeds, each with its sacred scriptures, doctrines, and particular history. But if one dug deep enough, their common root could be exposed. For Rodrigues this common root was lodged in Mesopotamia and associated with Zoroaster and the evil habit of the elites to mislead the common people by hiding the true doctrine under a coat of symbols. Mainly because of his opposition to Ricci-style missionary strategy, Rodrigues's writings were suppressed. Some of them got buried in archives and may still lie there; others were plagiarized by ideological opponents (for instance, Rodrigues's writings on Asian history and geography by Martino Martini) and then possibly destroyed; and much of the rest, especially Rodrigues's letters and reports, were noted in their time but forgotten by posterity. But overall, Rodrigues's writings are a splendid example of the influence of underground sources. His reports about Chinese religions were widely read by Jesuits and other orders and formed, as the basis of Niccolo Longobardi's treatise, a core argument of the opponents of the Jesuits in the Chinese Rites controversy. In this form they came to play a crucial but hitherto overlooked role in the downfall and prohibition of the Jesuit order in the eighteenth century.

The Buddha's Deathbed Confession

Rodrigues's ideas and scholarship burrowed their way into the minds of other missionaries. One of them was the Milanese Cristoforo BORRl (1583-1632) who lived in Saigon from 1610 to 1623. His report about Cochinchina, published in 1631, gave the distinction between the exoteric and esoteric teachings of Buddhism a fateful twist. He reported that Xaca had immediately after his enlightenment written books about the esoteric teaching:

Therefore returning home, he wrote several books and large volumes on this subject, entitling them, "Of Nothing;" wherein he taught that the things of this world, by reason of the duration and measure of time, are nothing; for though they had existence, said he, yet they would be nothing, nothing at present, and nothing in time to come, for the present being but a moment, was the same as nothing. (Pinkerton 1818:9.821)

He argued likewise about moral things, reducing everything to nothing. Then he gathered scholars, and the doctrine of nothing was spread all over the East. However, the Chinese were opposed to this doctrine and rejected it, whereupon Xaca "changed his mind, and retiring wrote several other great books, teaching that there was a real origin of all things, a lord of heaven, hell, immortality, and transmigration of souls from one body to another, better or worse, according to the merits or demerits of the person; though they do not forget to assign a son of heaven and hell for the souls of departed, expressing the whole metaphorically under the names of things corporeal, and of the joys and sufferings of this world" (pp. 821-82). While the Chinese gladly received the "external," modified teaching of Xaca, the teaching of nothing also survived, for instance, in Japan in the dominant "gensiu" (Jap. Zen-sha, Zen sect) (p. 822). According to Borri, it was exactly this acceptance in Japan that had the Buddha explain on his deathbed that the doctrine of nothingness was his true teaching:

The Japanese and others making so great account of this opinion of nothing, was the cause that when Xaca the author of it approached his death, calling together his disciples, he protested to them on the word of a dying man, that during the many years he had lived and studied, he had found nothing so true, nor any opinion so well grounded as was the sect of nothing; and though his second doctrine seemed to differ from it, yet they must look upon it as no contradiction or recantation, but rather a proof and confirmation of the first, though not in plain terms, yet by way of metaphors and parables, which might all be applied to the opinion of nothing, as would plainly appear by his books. (p. 822)

Of course, Borri's tale lacks all historical perspective and has the Buddha make decisions based on events (the introduction of Buddhism to China and Japan) that happened many centuries later. But for people who have no idea of the history of this religion, its attribution of motives to the founder must have sounded believable, and Borri's book was one of the early works on East Asia that was widely read and translated. This story, in my opinion, forms the kernel of the Buddha's "deathbed confession" tale. Borri appears to have spun it on the basis of information from Japan, from Rodrigues, and possibly also Vietnamese informants, in order to make sense of the different teachings of this religion whose founder is Xaca = Buddha. [???!!!] In the Cathechismus (sic) of Alexander de Rhodes, which was printed in Rome in 1651, the geographical references were removed, and the Story appeared in a more biographical form where not the Chinese but Buddha's immediate disciples rejected the original doctrine:

When he wanted to teach others this impious doctrine [of nothingness], so contrary to natural reason, they all abandoned him. Seeing this, he began, with the demons as his teachers, to teach another way filled with false stories in order to retain his disciples. He taught them the false doctrine of reincarnation, and at the same time taught the people the worship of idols, among whom he placed himself as their head, as if he were the creator and lord of heaven and earth .... Those who were more advanced in his impious doctrine were forbidden to divulge it to the public. ... As to his closest disciples, he led them to the abyss of atheism, holding that nothingness is the origin of all things, and that at death all things return to nothingness as to their ultimate end. (Phan 1998:250)

This tale soon mutated in an ominous way that again had its roots in early reports from Japan. Instead of first teaching about emptiness and subsequently "accommodating" Chinese or Indian sensibilities in a manner that resembles the Jesuit mission strategy, [???!!!] the founder of Buddhism was exposed as a liar and fraud who never told anyone about his nihilism and for forty-nine years preached an "exterior" doctrine he did not believe in. This resounded throughout Europe, thanks to the megaphone of Couplet's 1687 introduction to Confucius Sinarum Philosophus, and found its way into works such as Louis Daniel Lecomte's Nouveaux memoires sur l'etat present de la Chine (1696), Jean-Baptiste du Halde's Description de la Chine (1736), and scores of dictionaries, encyclopedias, travel accounts, and other books. Thus canonized, the Story presented the Buddha as a fraud, liar, and coward who needed to be prodded by the cold breath of death to reveal his nihilism and even then dared to do so only to his closest and dearest disciples. It combined elements from Jesuit letters and reports from Japan (particularly those regarding the Zen sect), Valignano's catechism, Rodrigues's reports, and Borri's and de Rhodes's tales and molded them into an easily understood deathbed confession story that not only exposed the founder's profound character flaw but also furnished a simple classification scheme for variants of his religion. The founder's disciples, so the story went, after his death formed two factions, an esoteric and an exoteric one. Soon a third faction that combined both teachings got added (App 2008a:29) and took care of whatever would not fit into the first two categories.

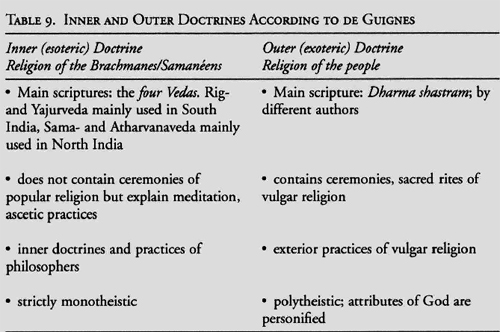

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, it was especially the Treatise on Some Points of the Religion of the Chinese (written by Niccolo Longobardi in 1624-26) that created waves because it stood at the center of the Chinese Rites controversy. This internal Jesuit document, whose core consisted of Rodrigues's reports of the 1610s and 1620s, had been leaked and published in 1676 by the Dominican friar Domingo NAVARRETE(1618-89) and was read, among many other European intellectuals, by the philosopher Gottfried Leibniz (Leibniz 2002). Longobardi's treatise stated that the use of symbols "gave birth in all nations to two kinds of science: a true and secret one, and a false and public one" (Leibniz 2002:122). The first was only possessed by the learned and kept secret, while the second constituted "a false appearance of popular doctrine," a mirage that the people, attached as they are to the bark of words, "took for the true teaching" instead of recognizing it as a "gross shadow that disguises truth" (p. 122). Longobardi explained, following Rodrigues:

The three sects of the Chinese entirely follow this kind of philosophizing. They have two kinds of doctrine: a secret one that they regard as true and that only the learned understand and teach encoded in figures; and the vulgar one which is a figure of the first and is regarded by the learned as false in the natural meaning of the words. (p. 122)

Longobardi also followed Rodrigues's lead in putting the three great Chinese religions in the evil transmission line by declaring them to be forms of atheism going back to "Zoroaster, the magus and prince of the Chaldeans" (pp. 128, 141).

Even opponents of Rodrigues such as Martino MARTINI (1614-61), who In 1651 traveled to Europe to defend Ricci's approach, drew information about Chinese religions from Rodrigues. In the introduction to his Novus Atlas Sinensis of 1655, Martini described the sect of Shakyamuni as follows:

The second sect is the idolatric one, called Xekiao. This pest infected China shortly after Christ's birth. It admits metempsychosis. It is of two kinds; one is internal and the other external. The latter [external or exoteric kind] teaches the worship of idols, portrays the transmigration of souls after death as a punishment for sins, and continually abstains from [eating] anything that lives. It is a ridiculous law that is disapproved of even by the clergy of these sectarians who consider it necessary to keep the ignorant people away from vice and to incite them to be virtuous. The internal [teaching of] metempsychosis is excellent and one of the best parts of moral philosophy since it regards the passions, those depraved inclinations of the soul, as emptiness [vacuitatem] and aims at victory over them. As long as this [victory] is not obtained, so they believe, the souls of those dominated by such feelings continue to migrate in the bodies of brute animals. [The inner teaching] does not believe in any reward or punishment after death, just a void [vacuum]. It asserts that there is no truth in this life unless it can be touched and that good and evil are just different viewpoints. (Martini 1665:8)

Athanasius KIRCHER'S China Illustrata (1667) was even more instrumental in promoting the esoteric/exoteric divide. The chapter titled "Parallels Between Chinese, Japanese, and Tartar Idolatry" presented these two "manners" as the two main kinds of Japanese religion and confirms the divide's sixteenth-century Japanese mission roots and the close association of Zen with the esoteric doctrine. Kircher wrote:

Lest I seem to be asserting something only on my own authority, I will quote here some words of Fr. Ludwig Gusmann in his Spanish language account: There are many sects in Japan which have been, and still are, different from each other, but these can be reduced to two main ones. The first denies that there is any other life than that which we perceive with our senses and that there is any reward for good works or punishment for crimes which we do in the world except those we get while we live on the earth. Persons who profess this view are called Xenxus [Jap. Zen-shu, Zen sect] .... As regards those who believe in an afterlife, there are two principal sects, and from these have come an infinite number of others. (Kircher 1987:131)

Like Rodrigues and Borri, Kircher used this division as a tool to bring order into East Asia's idolatries[???]:

Since the Japanese have borrowed their idolatrous religion from the Chinese, they have as great a variety of sects as the Chinese. These can be summarized under two headings. The first of these is those who deny an afterlife and who believe that there is no future punishment or reward for good works or evil. They lead an Epicurean life. This sect is called Xenxus Gap. Zen-sha, Zen sect] .... The others, who believe in immortality of the soul and an afterlife, are similar to the Pythagoreans in their rites and ceremonies. Most of the Chinese sages follow this theory. They worship an idol by the name of Omyto, commonly called Amida. (p. 131)

This portrayal pitches, like the early Jesuit reports of 1551 mentioned above, the (esoteric) Zen adherents against the (exoteric) Pure Land worshipers of Amida and is thus an example of a practice that even today is rampant in academia, namely, the projection of Japanese distinctions on China.