Chapter 8: Volney's Revolutions

"Orientalism" has been portrayed by Edward SAID in his eponymous book, first published in 1979, as a very influential, state-sponsored, essentially imperialist and colonialist enterprise. For Said, the Orientalist ideology was rooted in eighteenth-century secularization that threatened the traditional Christian European worldview. That worldview had been reigning for many centuries and was based on the "Biblical framework." Said held that "modern Orientalism derives from secularizing elements in eighteenth-century European culture" (1979:120) and pointed out the all-important role that the discovery of Oriental religions and languages played in the birth of Orientalism:

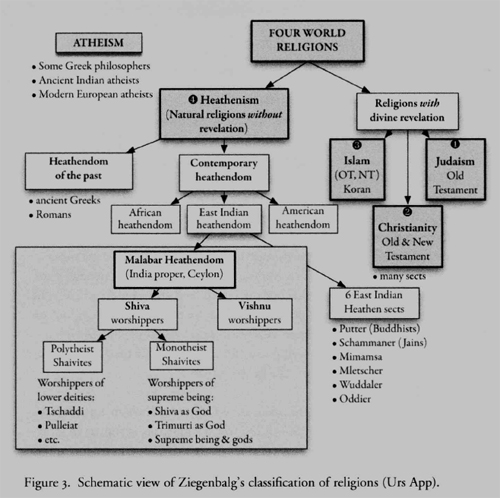

One, the expansion of the Orient further east geographically and further back temporally loosened, even dissolved, the Biblical framework considerably. Reference points were no longer Christianity and Judaism, with their fairly modest calendars and maps, but India, China, Japan, and Sumer, Buddhism, Sanskrit, Zoroastrianism, and Manu. (p. 120)

I quite agree with this. Curiously, though, only Islam -- which had the least potential of loosening or dissolving the biblical framework because it made itself use of it -- plays a role in Said's argument. The European discovery of other Asian religions is strangely absent: Zoroastrianism and Brahmanism are only briefly mentioned in the context of Anquetil-Duperron's studies (p. 76), Hinduism not at all, Confucius once in the context of Fenelon (p. 69), and Buddhism twice more, but (as in the quotation above) only as part of uncommented lists (pp. 232, 259). Focusing on political power and imperialist strategy rather than the power of religious ideology, Said was not in a position to answer how the "loosening" of the biblical framework was connected to the discovery of Asian religions and the genesis of modern Orientalism.

Robert IRWIN (2006:294) rightly criticized the "newly restrictive sense" that Said gave to the term Orientalism: "those who travelled, studied or wrote about the Arab world." Nevertheless, he declared himself "happy to accept this somewhat arbitrary delimitation of the subject matter" for the very convenient reason that "it is the history of Western studies of Islam, Arabic and Arab history and culture that interests me most" (p. 6). It is thus hardly surprising that non-Islamic oriental religions are as little discussed in Irwin's book-length study about Oriental ism as in Said's. For example, Buddhism -- Asia's most widespread religion -- is only once mentioned in passing, and the religions of Asia's most populous nations, India and China, play no role at all. While accusing Said of hating "religion in all its forms," harboring "anti-religious prejudice," and failing "properly to engage with the Christian motivations of the majority of pre-twentieth-century Orientalists" (p. 294), Irwin's portrayal of Anquetil-Duperron and of William Jones shows an almost Saidian lack of insight into religious motivations: Anquetil-Duperron's striking religiosity is completely ignored in favor of his "anti-imperialism" (pp. 125-26), and treatment of Jones's religious motivations is limited to Irwin's cursory remarks to the effect that Jones "hoped to find evidence in India for the Flood of Genesis" and had a "somewhat archaic and confused" ethnology in which "Greeks, Indians, Chinese, Japanese, Mexicans and Peruvians all descended from Noah's son, Ham" (p. 124).

Furthermore, Irwin criticizes Said for attributing far too much importance to Orientalism. In Irwin's view the "heyday of institutional Orientalism only arrived in the second half of the twentieth century." Before that time, Orientalism was a relatively insignificant affair given that its exponents, according to Irwin, usually were just "individual scholars, often lonely and eccentric men" driven by curiosity rather than colonialist and imperialist rapacity. This is reflected in the title of the original English edition of Irwin's book: "For Lust of Knowing."1 Irwin's Orientalists, "always few in number and rarely famous figures," were at best influential in literary, historical, theological, cultural, and, of course, oriental studies (p. 5) but had hardly any impact outside the literary world. For the most part they were just a bunch of relatively isolated "dabblers, obsessives, evangelists, freethinkers, madmen, charlatans, pedants, romantics" driven not by grand imperialist dreams but by "many competing agendas and styles of thought" (p. 7).

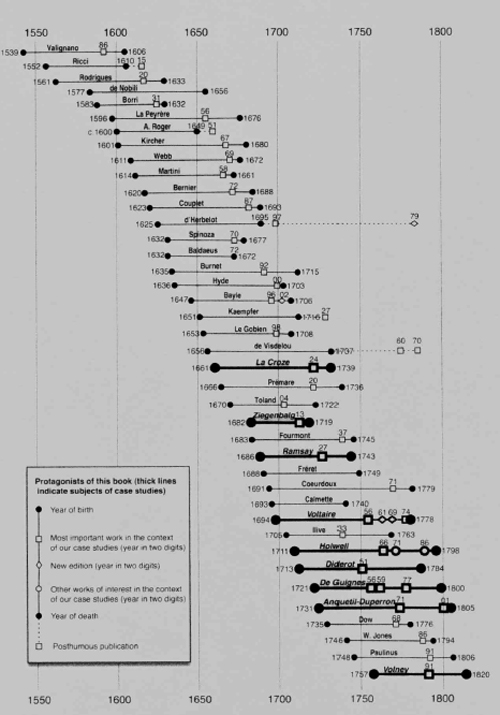

This final chapter examines a member of this eccentric crowd, Constantin Francoise Chasseboeuf VOLNEY (1757-1820), whose life span extends a bit beyond the period covered in this book. In Said's eyes, Volney was one of the most prominent "orthodox Orientalist authorities" (1979: 38) whose travel account (Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte, 1785-87) and reflections on the Turkish war (Considerations sur la guerre actuelle des Turcs, 1788) constituted "effective texts to be used by any European wishing to win in the Orient." Said thus saw Volney as a major instigator of Napoleon's imperialist invasion of Egypt (p. 81). Being "canonically hostile to Islam as a religion," the "canny Frenchman" (p. 81) was not engaged in some haphazard "innocent scholarly endeavor." Rather, as an archetypal exponent of "Orientalism as an accomplice to empire" (p. 333), he was fit to join William Jones near the top of Said's Orientalist blacklist.2

Said's critic Irwin, by astonishing contrast, portrays Volney as an Orientalist sharply critical of the collusion of religion and political tyranny and as one of the leading spokesmen against the French plan to invade Egypt. Irwin argues against Said that Volney was not just an opponent of Islam but of all religions, particularly of Christianity. Unlike Said, Irwin also mentions Volney's most influential book, The Ruins, which was published during the French Revolution in 1791. According to Irwin, "everybody read this book. It was a bestseller and the talk of the salons, spas and gaming rooms. Even Frankenstein's monster read it" (2006:135). But instead of enlightening the curious reader about this startling exception to Irwin's rule of little-read Orientalist dabblings -- after all, Volney's Ruins was among the most-read books of the revolutionary period and a smashing success by any standard -- Irwin complains that "no one reads Les Ruines nowadays. It is quite hard going" (p. 135). In fact, to keep our gaze on the period when attention spans were a bit longer and passions stronger, Volney's book rapidly caught the attention of a large public, and already in 1792 an anonymous English translation was published in London. Another sign of strong interest is that excerpts of the bestseller were printed in the form of broadsides and pamphlets from late 1792 on. The full English text was also widely available in pocket-sized, undated editions (Weir 2003:48). According to E. P. Thompson, the book was "more positive and challenging, and perhaps as influential, in English radical history as Paine's Age of Reason," and during the mid-1790s "the cognoscenti of the London Corresponding Society -- master craftsmen, shopkeepers, engravers, hosiers, printers -- carried [The Ruins] around with them in their pockets (Weir 2003:48). Among such craftsmen was young William Blake, one of the myriad readers influenced by Volney (pp. 48-55). Prominent statesmen were also among the admirers of the book, for example, Volney's friend Thomas Jefferson who, before his election as president of the United States of America, was so inspired by The Ruins that he took the time to translate no less than twenty of its twenty-four chapters into English and invited Volney to stay at Monticello (Chinard 1923),

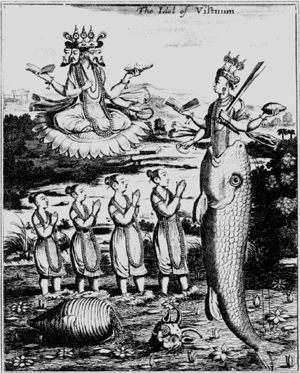

According to Irwin, the key question addressed in Volney's Ruins is "why the East was so impoverished and backward compared to the West," and a large part of Volney's answer consisted in the "prevalence of despotism in the East" (2006:135). Irwin does not mention the central role of religion in Volney's revolutionary analysis. While both Said and Irwin failed to remark on the centrality of religious tyranny and of the power of religious ideology in Volney's argument, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century readers certainly did not overlook this. Religion as humankind's most fundamental value system and primary source of conflicts plays a central role in The Ruins; in fact, more than half of its total volume is taken up by the famous Orientalist's fascinating survey of the world's religions and his revolutionary analysis of the origin and genealogy of religious ideas.

Holbach's System of Nature

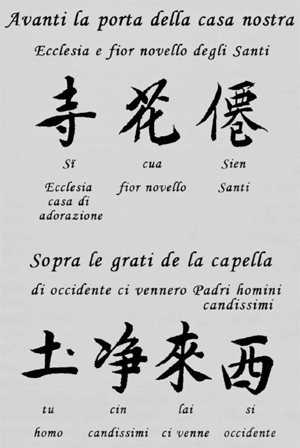

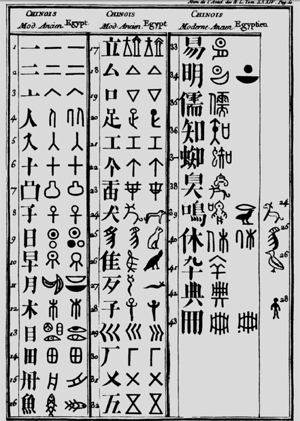

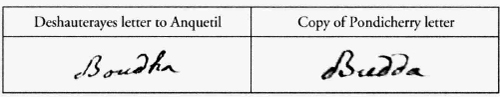

In 1780, the twenty-three-year-old Volney began to follow courses in Arabic given by Professor Deshauterayes of the College Royal. His teacher was known as a dogged opponent of de Guignes's farfetched theories about the Egyptian origin of the Chinese, and he also produced some translations and studies of Buddhism-related materials from Chinese.3 Volney also frequented the salon of Madame Helvetius, the widow of the famous naturalist and freethinker Claude-Adrien HELVETIUS (1717-71). In her salon, the word "atheism" -- which Bernhardus Varenius had 130 years earlier smuggled into his survey of religions -- had an entirely different, confident ring. Some Paris salons were teeming with skeptics, agnostics, and atheists, and the house of Madame Helvetius was their favorite hangout. Their bible was a two-volume book of 1770 titled le systeme de la nature that had appeared in London under the name of "Mirabaud, perpetual secretary and one of the forty members of the Academie Francaise." The name of the eminent Jean-Baptiste DE MIRABAUD (1675-1760) -- who had been in his tomb for a decade when this book was supposedly written -- was only a shield to protect the book's real author: the notorious materialist and radical Paul-Henri Dietrich, Baron D'HOLBACH (1723-1789). Holbach also happened to be a frequent visitor of Madame Helvetius's salon and became a dominating influence on young Volney.

Religion was, of course, a fashionable topic of conversation, as was the information about savages in various parts of the world that posed a continuing challenge to champions of the Bible. However, as Whiston and Lafitau and many others had proved, an author could bend the biblical narrative to a considerable degree without necessarily running the risk of being burned at the stake. In his pioneer study on the cult of fetish divinities (Du Culte des Dieux fetiches, 1760), Charles de BROSSES (1709-77) had achieved the feat of marrying primitive Africans to biblical perfection by arguing that primitive cults (such as African fetishism) only arose after the disappearance of original monotheism:

The human race had first received from God the immediate instructions adapted to the intelligence with which his goodness had equipped the humans. It is so surprising to see them subsequently fallen in a state of brute stupidity that one can hardly avoid regarding this as a just and supernatural punishment for being guilty of having forgotten the beneficial hand that had created them. (de Brosses 1760:15)

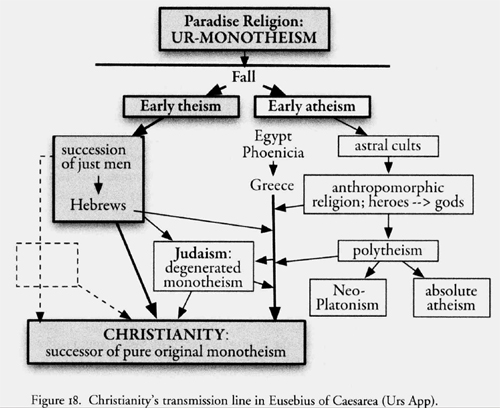

Only God's "immediate instructions," that is, divine revelation, could explain primeval monotheism since "the human spirit could not have found in itself what led it immediately to the pure principles of theism" (p. 207). De Brosses thus held that "all peoples began with correct notions of an intellectual religion that they later corrupted with the most stupid idolatries" (pp. 195-96). Looking back at the history of humanity from his perch at the apex of French academia, de Brosses saw increasing darkness and blindness pointing to an ancient common polytheism: "The most ancient memory of these people always presents polytheism as the common and ubiquitous system" (p. 204). But such common polytheism was not really the primeval human religion; rather, it was only the result of the biblical deluge: "One sees that the arts of primitive times were lost, that previously gained knowledge was buried under the waters, and that almost everywhere a pure state of barbarity reigned: natural effects of such a general and powerful revolution" (p. 204). Not unlike Giambattista VICO (1668-1744) in his Scienza nuova, de Brosses thus used the deluge as a means of marrying a secular scenario of primitivity and progress to the Christian scenario that ran exactly in the opposite direction, that is, from initial perfection to such degradation that divine intervention in the form of Jesus's incarnation became necessary.

This was a far cry from the radicalism of Baron d'Holbach, who turned this scheme of initial perfection and subsequent degeneration not just on its head but attempted to reduce it to rubble. For Holbach there was neither a paradise at the beginning of history nor a creator God; in fact, there was no beginning at all since some form of matter infused with energy had always existed and will always exist (Holbach 1770:1.26). "Had one observed nature without prejudice," he wrote, "one would have been convinced for ages that matter acts by its own force and has no need of any exterior impulsion to set it in motion" (1.22-23). Holbach thus frontally attacked the very foundation of the three Abrahamic religions:

Those who admit a cause exterior to matter are obliged to believe that this cause produced all the movement in this matter by giving it existence. This supposition is based on another, namely, that matter could begin to exist -- a hypothesis that until this moment has never been demonstrated by valid proofs. The summoning out of nothing, or creation, is no more than a word which cannot give us any idea of the formation of the universe; it has no meaning upon which the mind can rely. The notion becomes even more obscure when the creation or formation of matter is attributed to a spiritual being, that is, a being which has no analogy and no connection whatsoever with matter. (1.25-26)

Following Epicurus and Lucretius, Holbach's "nature" is eternal and inherently energetic (2:172). Instead of creation, he sees only transformations of the existing into different forms, "a transmigration, an exchange, a continuous circulation of the molecules of matter" (1:33). It is thus the inherent movement of matter, not some God, that accounts for production, growth, and alteration. From the formation of rocks inside the earth to that of suns and from the oyster to man, there is "a continuous progression, a perpetual chain of combinations and movements resulting in beings that differ among themselves only by the variety of their constituent elements and the combinations and proportions of these elements which give rise to infinitely diverse ways of existing and acting" (1.39). All constituents of the universe follow the order of nature; what may appear to be a disorder, for example, death, is in fact only a transition and a new combination of elements.4 For Holbach, everything is bound to matter infused with energy:

An intelligent being is a being that thinks, wills, and acts to achieve a goal. Now in order to think, will, and act as we do there is a need for organs and a goal that resembles ours. So, to say that nature is governed by an intelligence is to pretend that she is governed by a being equipped with organs, given that without organs there can be no perception, no idea, no intuition, no thought, no will, no plan, and no action. (1.66)

To speak of God or divinity or creation is thus only a sign of the ignorance of nature's energy; and man, supposedly the goal of creation, is only one of nature's myriad and fleeting transformations. He is an integral pan of nature obeying its universal laws of cause and effect and of self-preservation by attraction of the favorable and repulsion of me unfavorable (1:45-46). Nine decades before Charles Darwin, Holbach was not yet able to clarify man's origin and to determine whether he "has always been what he is" or "was obliged to pass through an infinity of successive developments" (1.80); due co lack of reliable data, Holbach left the question open while taking issue with the notion that man is the crown of creation:

Let us then conclude that man has no reason at all to regard himself as a privileged being in nature; he is subject to the same vicissitudes as all her other productions. His pretended prerogatives are based on an error. If he elevates himself by imagination above the globe that he inhabits and looks down upon his own species with an impartial eye, he will see that man, like every tree producing fruit in consequence of its species, acts by virtue of his particular energy and produces fruits -- actions, works -- that are equally necessary. He will feel that the illusion that makes him favor himself arises from being simultaneously spectator and pan of the universe. He will recognize that the idea of preeminence which he attaches to his being has no other basis than his self-interest and the predilection he has in favor of himself. (1.88-89)

But for Holbach such egoism is only natural since the goal of man, like that of nature as a whole, is self-preservation and well-being (1.133); and the realization that this goal necessitates cooperation with others and involves the happiness of others forms the basis of morality, law, politics, and education (1.139-47). In this manner Holbach attacked not only the cosmological and religious authority of the Judeo-Christian tradition and other forms of theism but also their exclusive claim to morality. Instead of commandments revealed on Mr. Sinai, Mosaic law, Confucian maxims, Christian catechisms, or Herbert's five common notions, Holbach proposed a universal natural basis of morality:

If man, according to his nature, is forced to desire his well-being, he is forced to love the means leading to it; it would be useless and perhaps unjust to demand that a man should be virtuous if he could only become so by rendering himself miserable. As soon as vice renders him happy, he must love vice; and if he sees inutility honored and crime rewarded, what interest would he find in working toward the happiness of his fellow creatures or restraining the fury of his passions? (I.151)

It is thus not through revealed scriptures and commandments from above that man's morality is assured but through self-interest that is healthy and informed enough to encompass fellow beings and the outside world. Gaining true ideas, that is, ideas based on nature and not imagination, is, according to Holbach, the only remedy for the ills of man (1:351). But from where do those ills originate in the first place? From illusions and false ideas; for "as soon as man's mind is filled with false ideas and dangerous opinions, his whole conduct tends to become a long chain of errors and depraved actions" (1.151). And since religion and its representatives, according to Holbach, concentrate on fostering such false ideas, they must be identified as the source of man's evils:

If we consult experience, we will see that it is in illusions and sacred opinions that we must search out the true source of that multitude of evils which almost everywhere overwhelms mankind. The ignorance of natural causes created the gods for him; imposture rendered them terrible to him; these fatal ideas haunted him without rendering him better; made him tremble without any benefit; filled his mind with chimeras; hindered the progress of his reason; and prevented him from seeking his happiness. (1.339)

The role of priestcraft in this perversion of nature was most objectionable to Holbach, and like the English deists, he loved describing the fatal results of the clergy's deception in the most graphic terms:

His fears rendered him the slave of those who deceived him under the pretext of his welfare; he committed evil when told that his gods demanded crimes; he lived in misfortune because they made him believe that the gods had condemned him to be miserable. He never dared to throw off his chains because he was given to understand that stupidity, the renunciation of reason, sloth of mind, and abjection of his soul were the sure means of obtaining eternal felicity. (1.339)

The importance of the subject of religion to Holbach is highlighted by the fact that he devoted the entire second volume of his System of Nature to it. Instead of primitive monotheism, Holbach saw a gradual development of religious cults and offered the following genealogy of monotheism:

The first theology of man was to fear and adore the elements themselves, material and coarse objects; then he extended his reverence to the agents that he imagined to preside over these elements: to powerful spirits, inferior spirits, heroes, or to men endowed with great qualities. While thinking about this, he believed he would simplify things by putting the whole of nature under the rule of a single agent, a sovereign intelligence, a spirit, a universal soul that set this nature and its parts in motion. Recurring from cause to cause, the mortals ended up seeing nothing at all, and it is in this obscurity that they placed their God. In this dark abyss their feverish imagination went on and on churning out chimeras which they will be smitten with until their knowledge of nature shall disabuse them of the phantoms that they have for so long adored in vain. (2.16)

For Holbach, theistic religion was a giant mistake; accordingly, he filled page after page of the second volume with the diagnosis of its origin, characteristics, and disastrous effects. Whether humanity had forever been on this globe or constituted a recent invention of nature that arose after one of nature's periodical revolutions: a look at the origin of various nations convinced Holbach that, contrary to the mosaic narrative, primitivity and savagery always marked the beginning (2.31). In this point he fully agreed with David Hume's analysis that was briefly mentioned in Chapter 5.

In contrast to Volney's Ruins, Holbach's System of Nature focuses on the Judeo-Christian tradition and its champions and rarely mentions other religions. Its argument aims at generality but betrays its theistically parochial nature by statements such as "all religions of the world show us God as an absolute ruler" (2.113); "all religions of the world posit a God continually occupied with rebuilding, repairing, undoing, rectifying his marvelous works" (2.115); "the thinkers of all centuries and all nations quarrel without respite ... about the attributes and qualities of a God that they have in vain occupied themselves with" (2.191); and "all nations recognize an evil sovereign God" (2.236). At any rate, what people call religion was for Holbach nothing but superstition:

By the admission even of the theologians, mankind is without religion; it only has superstitions. According to them, superstition is a badly understood and unreasonable cult of the deity: or else a cult offered to a false divinity. But where is a people or a clergy that agrees that its divinity is false and its cult unreasonable? How can one decide who is right and who is wrong? (2.291)

Only someone who freed himself of such superstition could be called truly religious; and that is exactly what Holbach understood by atheism.

What is really an atheist? It is a man who destroys the pernicious chimeras of humankind to lead the people back to nature, to experience, to reason. It is a thinker who has meditated matter, its energy, its characteristics and manners of action, and has no need of imagining ideal powers to explain the phenomena of the universe and the workings of nature. (2.320)

This was the kind of provocative discourse that evoked passionate discussions at Madame Helvetius's salon frequented by Volney and his friends. There is no doubt that Holbach's Epicurean view of nature and his radical vision of religion exerted a strong influence on Volney. But his focus on the Abrahamic religions prevented him from furnishing a panorama of religion that was truly global in scope. This was an opening for Volney. If Holbach had delivered his diagnosis in the System of Nature (1770) and presented a therapy in his Catechisme de la nature (1790), Volney offered the former in The Ruins (1791) and the latter in his Natural law or the catechism of the French people (1793).